Two Decades of Real-World Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Evolving Treatment and Outcomes in China with Reference to the United States

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

2.2. Variables and Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

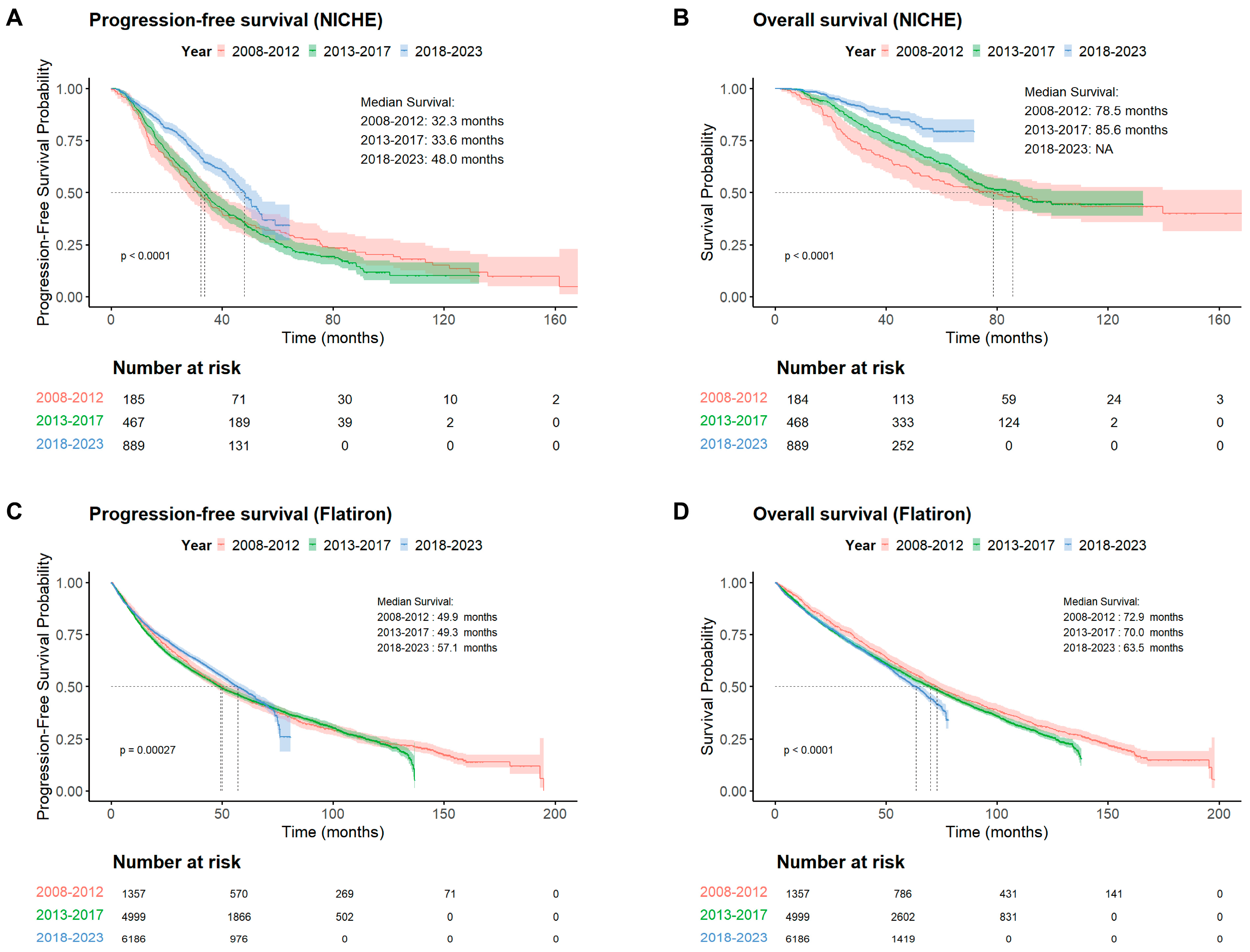

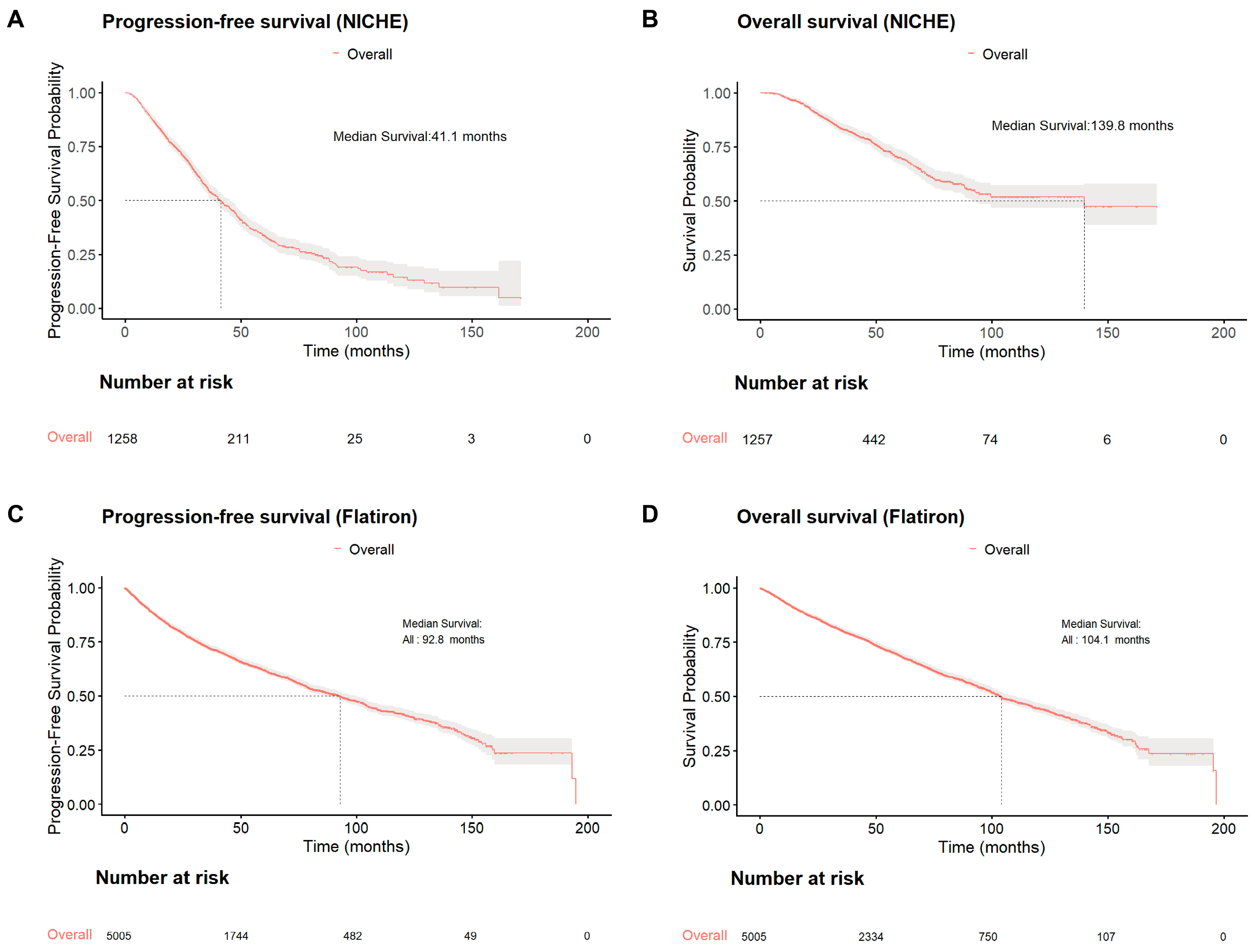

3.1. Survival Improvement Among Chinese Patients with NDMM

3.2. Benchmarking Against US Real-World Outcomes

3.3. Exploring Potential Reasons for Improved Survival

3.3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Population Profile

3.3.2. Age Subgroup Analysis

3.3.3. Evolution of Induction Therapy

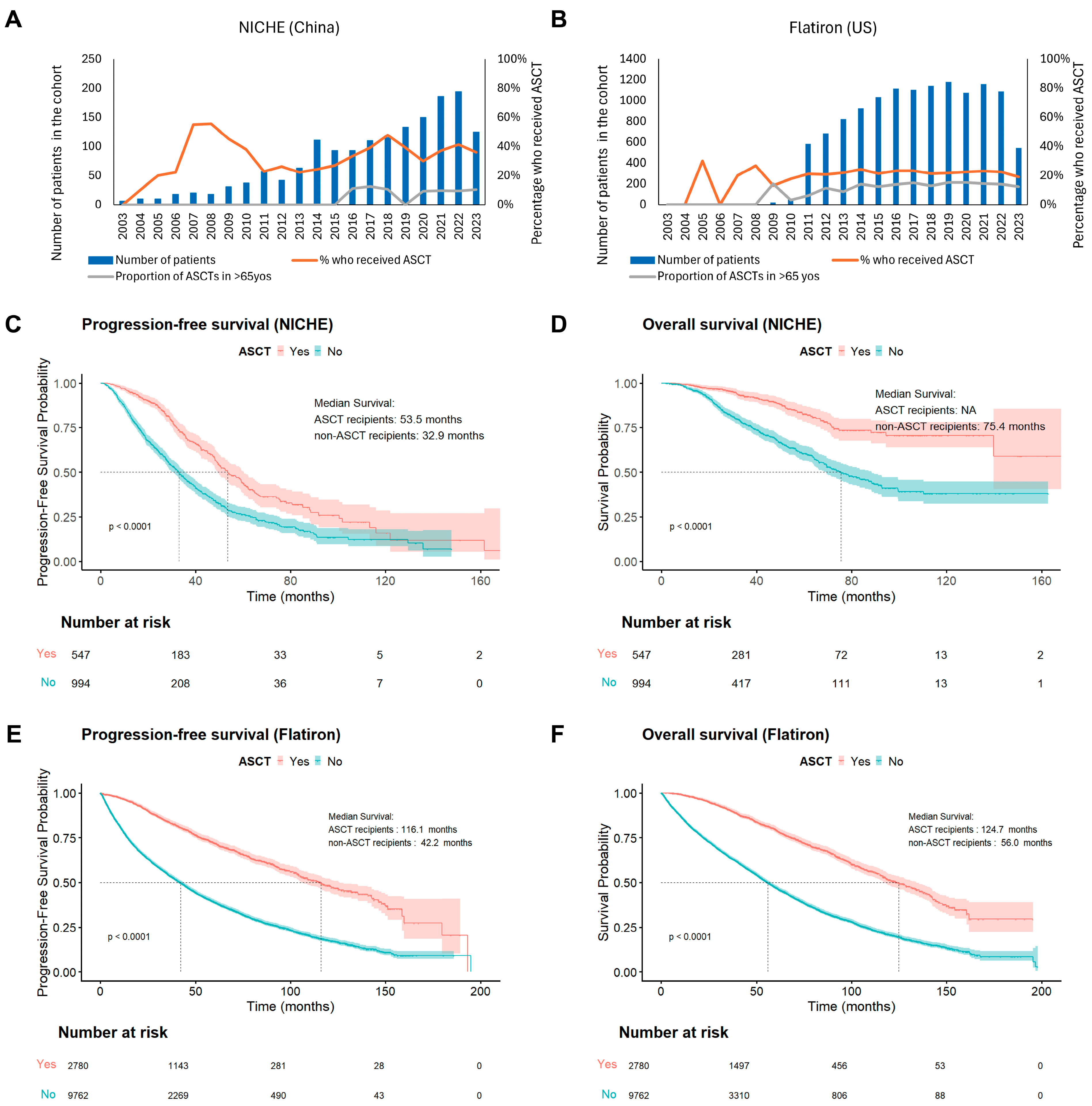

3.3.4. ASCT Utilization and Trends

3.3.5. Maintenance Trends

3.4. Prognostic Factors for Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malard, F.; Neri, P.; Bahlis, N.J.; Terpos, E.; Moukalled, N.; Hungria, V.T.M.; Manier, S.; Mohty, M. Multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (IARC) IAfRoC. Cancer Today (GLOBOCAN 2022): Multiple Myeloma—Country Profiles and Age-Standardised Incidence Rates; IARC: Lyon, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, X.; Duan, G.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, N.; Wen, L.; Qi, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J. The burden of multiple myeloma in China: Trends from 1990 to 2021 and forecasts for 2050. Cancer Lett. 2025, 611, 217440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Niu, D.; Ye, E.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Hou, X.; Wu, J. Secular Trends in the Burden of Multiple Myeloma From 1990 to 2019 and Its Projection Until 2044 in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 938770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, P.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Boccadoro, M.; Quach, H.; Ho, P.J.; Beksac, M.; Hulin, C.; Antonioli, E.; Leleu, X.; Mangiacavalli, S.; et al. Daratumumab, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facon, T.; Kumar, S.K.; Plesner, T.; Orlowski, R.Z.; Moreau, P.; Bahlis, N.; Basu, S.; Nahi, H.; Hulin, C.; Quach, H.; et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): Overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Williamson, M.; Ogbu, U.; Surinach, A.; Arndorfer, S.; Hong, W.J. Front-line treatment patterns in multiple myeloma: An analysis of U.S.-based electronic health records from 2011 to 2019. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 5866–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Maihemaiti, A.; Ren, L.; Lan, T.; Zhou, C.; Li, P.; Wang, P.; et al. The evolving diagnosis and treatment paradigms of multiple myeloma in China: 15 years’ experience of 1256 patients in a national medical center. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9604–9614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Lobato, L.G.; de Daniel, A.; Pereira, A.; Fernández de Larrea, C.; Tovar, N.; Cibeira, M.T.; Moreno, D.F.; Mateos, J.M.; Llobet, N.; Carcelero, E.; et al. Attrition rates and treatment outcomes in multiple myeloma: Real-world data over a 40-year period. Blood Cancer J. 2025, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Almaguer, D.; de Moraes Hungria, V.T. Multiple myeloma in Latin America. Hematology 2022, 27, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Chamseddine, N.; El-Cheikh, J.; Hanna, C.; Moukadem, W.; Nasr, F.; Younis, A.; Bazarbachi, A. Management of Multiple Myeloma in the Middle East: Unmet Needs, Challenges and Perspective. Clin. Hematol. Int. 2022, 4, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, L.; Naci, H.; Wagner, A.K.; Guan, X. Cancer drug indication approvals in China and the United States: A comparison of approval times and clinical benefit, 2001-2020. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 45, 101055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Shi, Y.; Song, J.; Cao, M.; Sun, A.; Liu, S.; Chang, S.; Zhao, Z. Impact of competition on reimbursement decisions for cancer drugs in China: An observational study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 50, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Mo, X.; Zhao, J.; Ming, J.; Liu, J.; Wei, T. HPR83 China’s National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) Negotiation: Value Considerations and Key Factors Influencing Payment Standards. Value Health 2025, 28, S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Cheng, T.; Qiu, L.; Wang, X.; Xia, Z.; An, G. Current treatment paradigm and survival outcomes among patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in China: A retrospective multicenter study. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 20, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Banerjee, R.; Khan, A.M.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Afghahi, A.; Afrough, A.; Janakiram, M.; Wang, B.; Cowan, A.J.; et al. Carfilzomib prescribing patterns and outcomes for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: A real-world analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2025, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, B.; Einsele, H.; Schecter, J.M.; Deraedt, W.; Lendvai, N.; Slaughter, A.; Lonardi, C.; Nair, S.; He, J.; Kharat, A.; et al. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (1–3 prior lines): Flatiron database. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 5062–5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durie, B.G.M.; Hoering, A.; Abidi, M.H.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Epstein, J.; Kahanic, S.P.; Thakuri, M.; Reu, F.; Reynolds, C.M.; Sexton, R.; et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, J. The Evolving Treatment Paradigms and Outcomes in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Patients Who Receive Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in China: A Real-World Observational Study. Blood 2024, 144, 6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langseth, Ø.O.; Myklebust, T.; Johannesen, T.B.; Hjertner, Ø.; Waage, A. Incidence and survival of multiple myeloma: A population-based study of 10,524 patients diagnosed 1982–2017. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 191, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasvolsky, O.; Marcoux, C.; Dai, J.; Milton, D.R.; Tanner, M.R.; Syed, N.; Bashir, Q.; Srour, S.; Saini, N.; Lin, P.; et al. Trends in Outcomes After Upfront Autologous Transplant for Multiple Myeloma Over Three Decades. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2024, 30, 772.e1–772.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.K.; Barlogie, B.; van Rhee, F.; Zangari, M.; Walker, B.A.; Rosenthal, A.; Schinke, C.; Thanendrarajan, S.; Davies, F.E.; Hoering, A.; et al. Long-term outcomes after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.K.; Buadi, F.K.; Rajkumar, S.V. Pros and cons of frontline autologous transplant in multiple myeloma: The debate over timing. Blood 2019, 133, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildes, T.M.; Finney, J.D.; Fiala, M.; Gao, F.; Vij, R.; Stockerl-Goldstein, K.; Carson, K.R.; Mikhael, J.; Colditz, G. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant in older adults with multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015, 50, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, C.; Muffly, L.S.; Rezvani, A.; Lowsky, R.; Iberri, D.J.; Craig, J.K.; Frank, M.J.; Johnston, L.J.; Liedtke, M.; Negrin, R.; et al. Outcomes with autologous stem cell transplant vs. non-transplant therapy in patients 70 years and older with multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gu, S.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, P. Clinical benefit loss in myeloma patients declining autologous stem cell transplantation: A real-world study. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Q.; Braunstein, M.; Buck, T.; Chmielewski, C.; Hartmann, B.; Janakiram, M.; McMahon, M.A.; Romundstad, L.; Steele, L.; Usmani, S.Z.; et al. Overcoming Barriers to Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Multiple Myeloma: Recommendations from a Multidisciplinary Roundtable Discussion. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Shan, C.; Wang, L.; Ye, D.; Luo, D.; Zou, H.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, X.Q.; et al. Shared decision-making about autologous stem cell transplantation: A qualitative study of older patients and physicians. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2025, 73, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrash, S.; Flahavan, E.M.; Xu, T.; Ma, E.; Karve, S.; Hong, W.J.; Jirau-Lucca, G.; Nixon, M.; Ailawadhi, S. Treatment patterns and outcomes according to cytogenetic risk stratification in patients with multiple myeloma: A real-world analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2022, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Yan, W.; Mery, D.; Liu, J.; Fan, H.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Sui, W.; Deng, S.; Zou, D.; et al. Development and validation of an individualized and weighted Myeloma Prognostic Score System (MPSS) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Mao, X.; Liu, J.; Fan, H.; Du, C.; Li, Z.; Yi, S.; Xu, Y.; Lv, R.; Liu, W.; et al. The impact of response kinetics for multiple myeloma in the era of novel agents. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 2895–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Liu, Y.; Lv, R.; Yan, W.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Du, C.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S.; Deng, S.; et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization reveals the evolutionary biology of minor clone of gain/amp(1q) in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2024, 38, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NICHE—China | Flatiron—United States | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | 2018–2023 | Total | 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | 2018–2023 | Total | |

| N (%) | 64 (3.95) | 185 (11.41) | 470 (28.98) | 903 (55.67) | 1622 | 40 (<1.0) | 1357 (10.79) | 4999 (39.73) | 6186 (49.17) | 12,582 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 55.5 (37–74) | 54.0 (32–83) | 56.5 (25–78) | 58.0 (25–80) | 57.0 (25–83) | 61.5 (42–77) | 67.0 (23–85) | 68.0 (25–85) | 69.0 (19–85) | 68.0 (19–85) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 18–49 | 19 (29.69) | 64 (34.59) | 123 (26.17) | 174 (19.27) | 380 (23.43) | 5 (12.50) | 109 (8.03) | 316 (6.32) | 347 (5.61) | 777 (6.17) |

| 50–65 | 37 (57.81) | 95 (51.35) | 284 (60.43) | 528 (58.47) | 944 (58.20) | 22 (55.00) | 495 (36.48) | 1783 (35.67) | 1955 (31.60) | 4255 (33.82) |

| 66–70 | 5 (7.81) | 19 (10.27) | 42 (8.94) | 127 (14.06) | 193 (11.90) | 10 (25.00) | 216 (15.92) | 854 (17.08) | 1105 (17.86) | 2185 (17.37) |

| 71+ | 3 (4.69) | 7 (3.78) | 21 (4.47) | 74 (8.19) | 105 (6.47) | 3 (7.50) | 537 (39.57) | 2046 (40.93) | 2779 (44.92) | 5365 (42.64) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 43 (67.19) | 123 (66.49) | 280 (59.57) | 499 (55.26) | 945 (58.26) | 23 (57.50) | 716 (52.76) | 2706 (54.13) | 3357 (54.56) | 6820 (54.20) |

| Female | 21 (32.81) | 62 (33.51) | 190 (40.43) | 404 (44.74) | 677 (41.74) | 17 (42.50) | 641 (47.24) | 2293 (45.87) | 2811 (45.44) | 5762 (45.80) |

| M:F | 2.05 | 1.98 | 1.47 | 1.24 | 1.4 | 1.35 | 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.20 | 1.18 |

| ISS stage, n (%) | ||||||||||

| I | 11 (18.97) | 39 (21.55) | 88 (19.60) | 195 (22.47) | 333 (21.40) | 7 (39.13) | 195 (30.36) | 901 (33.53) | 1261 (33.97) | 2364 (33.46) |

| II | 28 (48.28) | 73 (40.33) | 168 (37.42) | 304 (35.02) | 573 (36.83) | 7 (30.43) | 247 (37.76) | 894 (33.49) | 1226 (32.76) | 2374 (33.60) |

| III | 19 (32.76) | 69 (38.12) | 193 (42.98) | 369 (42.51) | 650 (41.77) | 5 (30.43) | 206 (31.87) | 879 (32.98) | 1238 (33.26) | 2328 (32.95) |

| Missing | 6 (9.38) | 4 (2.16) | 21 (4.47) | 35 (3.88) | 66 (4.07) | 21 (52.50) | 709 (52.25) | 2325 (46.51) | 2461 (39.78) | 5516 (43.84) |

| Myeloma isotype, n (%) | ||||||||||

| IgG | 22 (34.38) | 105 (56.76) | 222 (47.23) | 430 (47.72) | 779 (48.36) | 31 (77.50) | 792 (61.83) | 2820 (59.43) | 3475 (58.09) | 7118 (59.08) |

| IgA | 21 (32.81) | 43 (23.24) | 106 (22.55) | 197 (21.86) | 367 (22.78) | 6 (15.00) | 258 (20.14) | 965 (20.34) | 1241 (20.75) | 2470 (20.50) |

| Light chain | 14 (21.88) | 27 (14.59) | 97 (20.64) | 196 (21.75) | 329 (20.42) | 3 (7.50) | 217 (16.94) | 901 (18.99) | 1200 (20.06) | 2321 (19.26) |

| IgD | 2 (3.13) | 7 (3.78) | 35 (7.45) | 53 (5.88) | 95 (5.90) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (0.23) | 20 (0.42) | 25 (0.42) | 48 (0.40) |

| IgM | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.21) | 6 (0.67) | 7 (0.43) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (0.78) | 35 (0.74) | 39 (0.65) | 84 (0.70) |

| Other | 5 (7.81) | 3 (1.62) | 9 (1.91) | 19 (2.11) | 34 (2.11) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.08) | 4 (0.08) | 2 (0.03) | 7 (0.06) |

| Missing | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.50) | 11 (1.62) | 0 (0.00) | 76 (5.60) | 254 (5.08) | 204 (3.30) | 534 (4.24) |

| Cytogenetic risk at diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Standard | 13 (65.00) | 119 (73.91) | 339 (74.67) | 625 (77.26) | 1096 (75.90) | - | 311 (73.87) | 1748 (76.27) | 2557 (74.16) | 4616 (74.92) |

| High * | 7 (35.00) | 185 (11.41) | 115 (25.33) | 184 (22.74) | 348 (24.10) | - | 110 (26.13) | 544 (23.73) | 891 (25.84) | 1545 (25.08) |

| Missing | 44 (68.75) | 24 (12.97) | 16 (3.40) | 94 (10.41) | 178 (10.97) | 40 (100.00) | 936 (68.98) | 2707 (54.15) | 2738 (44.26) | 6421 (51.03) |

| Duration of follow-up | ||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 52.53 (28.33, 105.45) | 56.30 (26.42, 92.45) | 62.97 (34.83, 82.45) | 28.90 (19, 42.43) | 35.64 (22.29, 59.08) | 183.30 (142.97, 226.20) | 63.77 (26.87, 121.27) | 55.20 (20.77, 91.03) | 30.07 (15.57, 49.37) | 38.83 (17.80, 69.53) |

| NICHE—China | Flatiron—United States | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | 2018–2023 | Total | 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | 2018–2023 | Total | |

| N | 56 | 159 | 407 | 702 | 1324 | 27 | 604 | 2099 | 2302 | 5032 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 53.4 (7.6) | 52 (7.8) | 53.7 (7.7) | 54.3 (7.4) | 53.78776 (7.5) | 55.96 (6.5) | 55.73 (7.5) | 56.64 (7.1) | 56.82 (6.9) | 56.61 (7.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 37 (66.1) | 105 (66) | 241 (59.2) | 392 (55.8) | 775 (58.5) | 18 (66.7) | 328 (54.3) | 1168 (54.6) | 1279 (55.6) | 2793 (55.5) |

| Female | 19 (33.9) | 54 (34) | 166 (40.8) | 310 (44.2) | 549 (41.5) | 9 (33.3) | 276 (45.7) | 931 (45.4) | 1023 (44.4) | 2239 (44.5) |

| M:F | 1.95 | 1.94 | 1.45 | 1.26 | 1.41 | 2 | 1.19 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| ISS stage, n (%) | ||||||||||

| I | 9 (17.6) | 38 (24.5) | 76 (19.6) | 158 (23.5) | 281 (22.2) | 5 (38.5) | 108 (33.9) | 443 (37.5) | 611 (42.1) | 1167 (39.3) |

| II | 24 (47.1) | 62 (40) | 140 (36.1) | 244 (36.3) | 470 (37.1) | 5 (38.5) | 121 (37.9) | 391 (33.0) | 410 (28.3) | 927 (31.3) |

| III | 18 (35.3) | 55 (35.5) | 172 (44.3) | 271 (40.3) | 516 (40.7) | 3 (23.0) | 90 (28.2) | 349 (29.5) | 430 (29.6) | 872 (29.4) |

| Missing | 5 (8.93) | 4 (2.52) | 19 (4.67) | 29 (4.13) | 57 (4.31) | 14 (51.9) | 285 (47.2) | 916 (43.6) | 851 (37.0) | 2066 (41.0) |

| Myeloma isotype, n (%) | ||||||||||

| IgG | 21 (37.5) | 87 (54.7) | 187 (45.9) | 327 (46.6) | 622 (47) | 21 (80.8) | 339 (60.4) | 1176 (59.4) | 1294 (59.4) | 2830 (59.6) |

| IgA | 15 (26.8) | 38 (23.9) | 94 (23.1) | 148 (21.1) | 295 (22.3) | 3 (11.5) | 107 (119.1) | 381 (19.3) | 421 (19.3) | 912 (19.2) |

| Light chain | 14 (25) | 25 (15.7) | 83 (20.4) | 163 (23.2) | 285 (21.5) | 2 (7.7) | 113 (20.1) | 397 (20.1) | 442 (20.3) | 954 (20.1) |

| IgD | 2 (3.6) | 7 (4.4) | 34 (8.4) | 45 (6.4) | 88 (6.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.18) | 10 (0.47) | 13 (0.51) | 24 (0.50) |

| IgM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (0.57) | 10 (0.50) | 22 (0.46) |

| Other | 4 (7.1) | 2 (1.3) | 9 (2.2) | 19 (2.7) | 34 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1(0.18) | 3 (0.14) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.08) |

| Missing | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.7) | 43 (7.1) | 120 (5.7) | 122 (5.3) | 286 (5.7) |

| Cytogenetic risk at diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Standard | 11 (68.8) | 101 (74.3) | 285 (72.7) | 469 (74.8) | 866 (74) | - | 145 (70.0) | 746 (76.3) | 934 (73.0) | 1825 (74.1) |

| High * | 5 (31.3) | 35 (25.7) | 107 (27.3) | 158 (25.2) | 305 (26) | - | 62 (30.0) | 232 (23.7) | 345 (27.0) | 639 (25.9) |

| Missing | 40 (71.43) | 23 (14.47) | 15 (3.69) | 75 (10.68) | 153 (11.56) | 27 (100.00) | 397 (65.7) | 1121 (53.4) | 1023 (44.4) | 2568 (51.0) |

| Duration of follow-up | ||||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 51.8 (27.8, 104.0) | 56.4 (28.9, 97.3) | 63.3 (35.1, 82.9) | 14.8 (29.5, 20.1) | 38.0 (23.5, 61.3) | 202.4 (157.2, 232.0) | 90.9 (39.6, 146.4) | 75.5 (29.1, 100.5) | 33.9 (18.5, 53.2) | 48.4 (22.3, 82.5) |

| NICHE—China | Flatiron—United States | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||||||

| Variables | N | Event | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | N | Event | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| PFS | ||||||||||||

| ISS stage | ||||||||||||

| Stage 1/2 vs. Stage 3 | 867 | 410 | 0.720 (0.623–0.832) | <0.001 | 0.703 (0.582–0.849) | <0.003 | 4724 | 1607 | 0.539 (0.501–0.579) | <0.001 | 0.609 (0.551–0.673) | <0.001 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||||||||||||

| Standard vs. High | 1083 | 532 | 0.776 (0.659–0.915) | 0.003 | 0.754 (0.609–0.934) | 0.010 | 4616 | 1545 | 0.629 (0.569–0.696) | <0.001 | 0.622 (0.559–0.693) | <0.001 |

| Induction regimen | ||||||||||||

| PIs + IMIDs vs. Cytotoxics/PI/IMIDs-based | 633 | 217 | 0.691 (0.587–0.813) | <0.001 | 0.797 (0.643–0.987) | 0.037 | 6315 | 2315 | 0.724 (0.686–0.764) | <0.001 | 0.828 (0.742–0.924) | <0.001 |

| CD38 mAb vs. Cytotoxics/PI/IMIDs-based | 173 | 38 | 0.591 (0.421–0.828) | 0.002 | 0.442 (0.272–0.718) | 0.001 | 1568 | 272 | 0.616 (0.556–0.683) | <0.001 | 0.709 (0.585–0.858) | <0.001 |

| ASCT | ||||||||||||

| Yes vs. No | 548 | 215 | 0.492 (0.420–0.577) | <0.001 | 0.625 (0.508–0.769) | <0.001 | 2780 | 808 | 0.343 (0.317–0.371) | <0.001 | 0.427 (0.371–0.490) | <0.001 |

| Maintenance | ||||||||||||

| Yes vs. No | 101 | 57 | 0.585 (0.444–0.771) | 0.0001 | 0.695 (0.509–0.948) | 0.022 | 4453 | 1395 | 0.621 (0.587–0.656) | <0.001 | 0.824 (0.736–0.922) | <0.001 |

| OS | ||||||||||||

| ISS stage | ||||||||||||

| Stage 1/2 vs. Stage 3 | 867 | 185 | 0.557 (0.454–0.683) | <0.001 | 0.554 (0.419–0.731) | <0.001 | 4724 | 1591 | 0.539 (0.501–0.579) | <0.001 | 0.588 (0.532–0.650) | <0.001 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||||||||||||

| Standard vs. High | 1083 | 260 | 0.686 (0.548–0.859) | 0.001 | 0.661 (0.486–0.898) | 0.008 | 4616 | 1743 | 0.601 (0.544–0.665) | <0.001 | 0.587 (0.527–0.653) | <0.001 |

| Induction regimen | ||||||||||||

| PIs + IMIDs vs. Cytotoxics/PI/IMIDs-based | 633 | 72 | 0.484 (0.370–0.632) | <0.001 | 0.576 (0.398–0.833) | 0.003 | 6315 | 2468 | 0.723 (0.685–0.764) | <0.001 | 0.915 (0.819–1.002) | 0.115 |

| CD38 mAb vs. Cytotoxics/PI/IMIDs-based | 173 | 14 | 0.526 (0.293–0.946) | 0.032 | 0.569 (0.262–1.238) | 0.155 | 1568 | 356 | 0.759 (0.685–0.842) | <0.001 | 1.040 (0.856–1.264) | 0.691 |

| ASCT | ||||||||||||

| Yes vs. No | 548 | 73 | 0.357 (0.277–0.461) | <0.001 | 0.427 (0.304–0.600) | <0.001 | 2780 | 649 | 0.344 (0.319–0.372) | <0.001 | 0.442 (0.385–0.508) | <0.001 |

| Maintenance | ||||||||||||

| Yes vs. No | 101 | 30 | 0.484 (0.330–0.711) | <0.001 | 0.572 (0.370–0.884) | 0.012 | 4453 | 1575 | 0.633 (0.599–0.670) | <0.001 | 0.847 (0.757–0.948) | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Shu, M.; Chung, H.; Cui, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, W.; Bai, Q.; Dai, N.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; et al. Two Decades of Real-World Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Evolving Treatment and Outcomes in China with Reference to the United States. Cancers 2026, 18, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010053

Xu J, Shu M, Chung H, Cui J, Liu Y, Yan W, Bai Q, Dai N, Li L, Zhou J, et al. Two Decades of Real-World Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Evolving Treatment and Outcomes in China with Reference to the United States. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jingyu, Meng Shu, Hsingwen Chung, Jian Cui, Yuntong Liu, Wenqiang Yan, Qirui Bai, Ning Dai, Lingna Li, Jieqiong Zhou, and et al. 2026. "Two Decades of Real-World Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Evolving Treatment and Outcomes in China with Reference to the United States" Cancers 18, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010053

APA StyleXu, J., Shu, M., Chung, H., Cui, J., Liu, Y., Yan, W., Bai, Q., Dai, N., Li, L., Zhou, J., Li, Y., Du, C., Deng, S., Sui, W., Xu, Y., Qiu, H., Qiu, L., & An, G. (2026). Two Decades of Real-World Study in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Evolving Treatment and Outcomes in China with Reference to the United States. Cancers, 18(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010053