Association Between SGLT2 Inhibitor Use and Reduced Risk of Liver-Related Events, Including Hepatocellular Carcinoma, in Diabetic Patients with Viral Hepatitis: A Nationwide Cohort Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Confounding Variables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Subsection

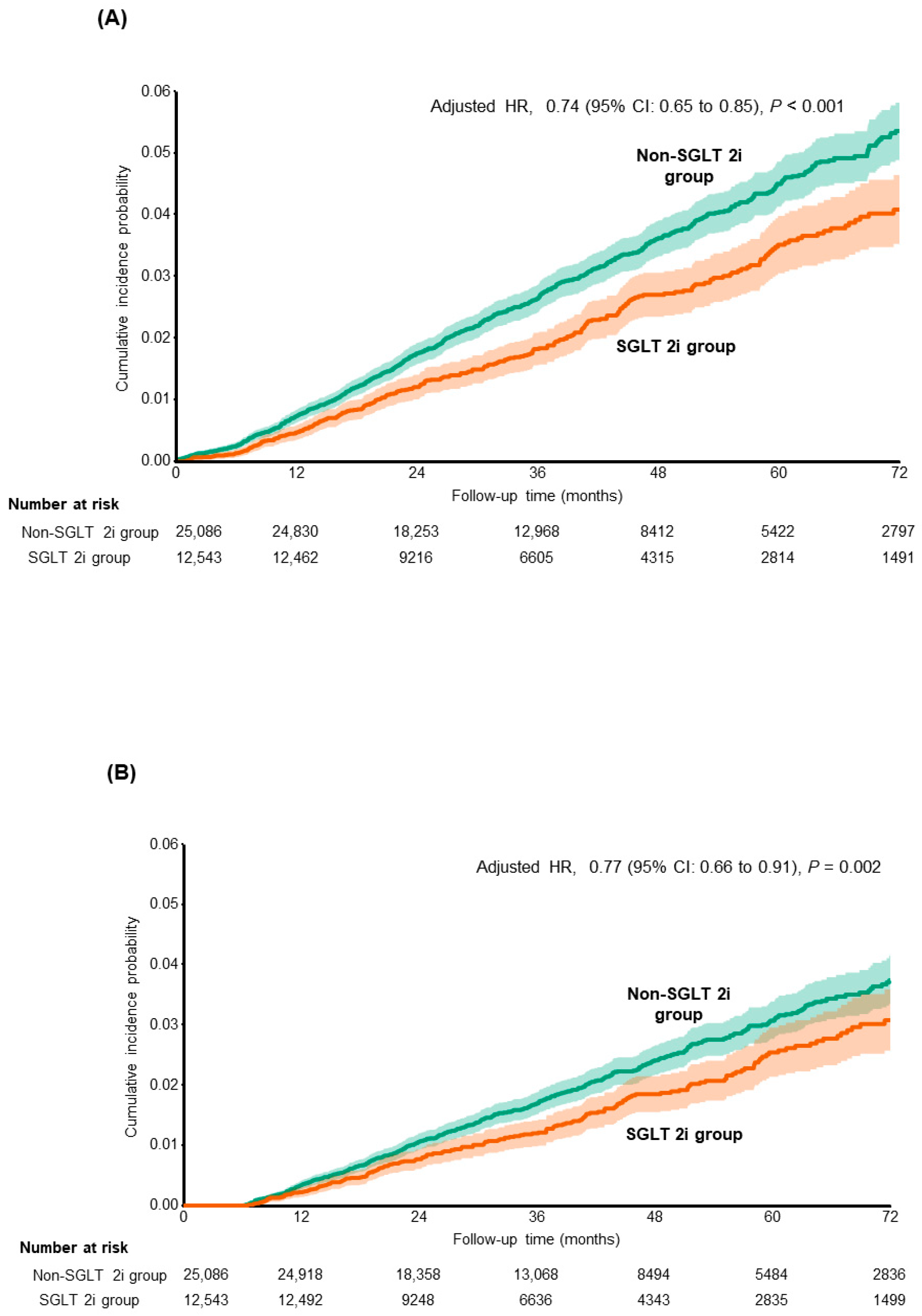

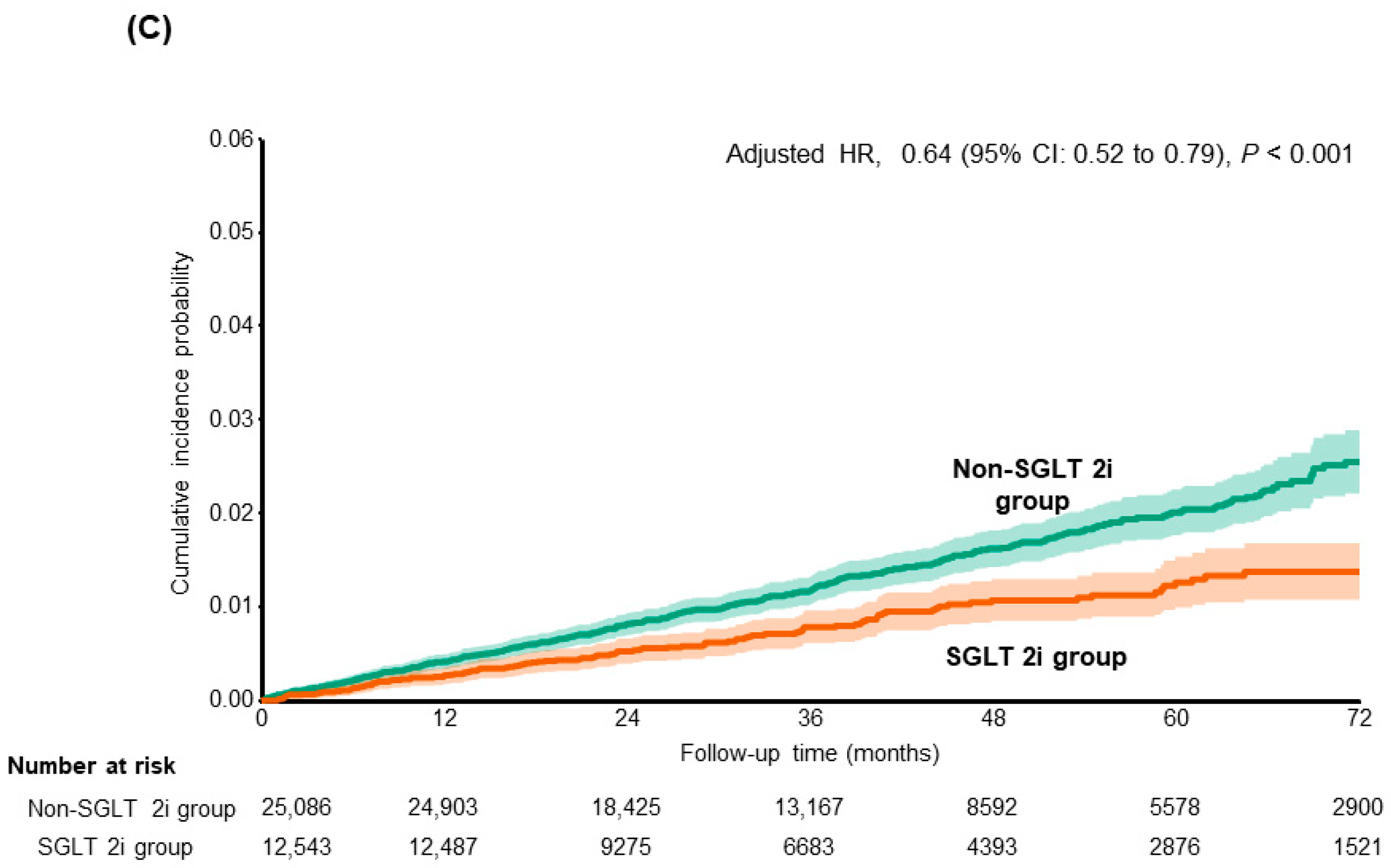

3.2. Risk of Composite Liver-Related Complications Including HCC

3.3. Risk of Mortality and Development of Cirrhosis

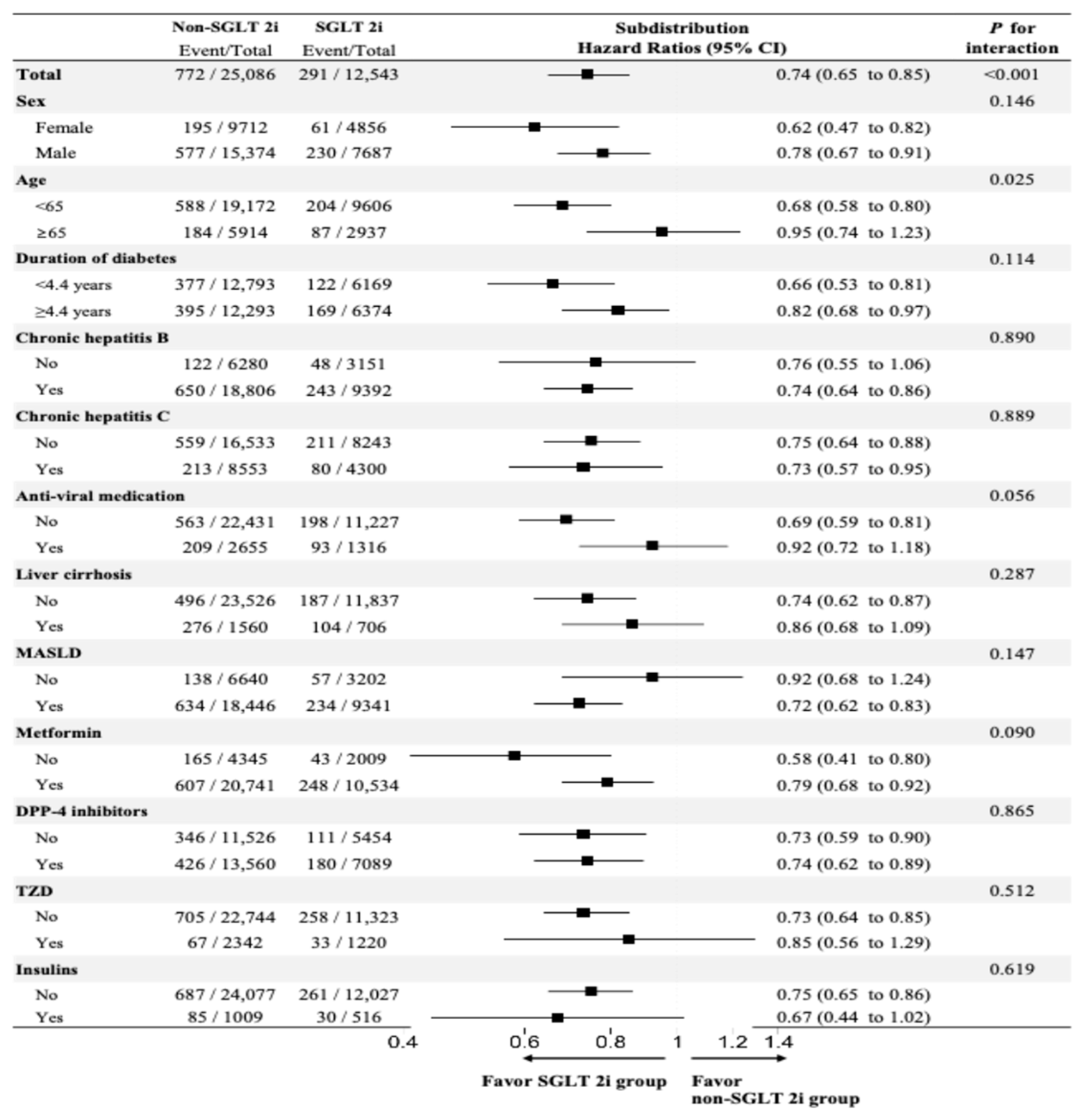

3.4. Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Schweitzer, A.; Horn, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Krause, G.; Ott, J.J. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumgay, H.; Arnold, M.; Ferlay, J.; Lesi, O.; Cabasag, C.J.; Vignat, J.; Laversanne, M.; McGlynn, K.A.; Soerjomataram, I. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serfaty, L. Metabolic Manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus. Clin. Liver Dis. 2017, 21, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-W.; Wang, T.-C.; Lin, S.-C.; Chang, H.-Y.; Chen, D.-S.; Hu, J.-T.; Yang, S.-S.; Kao, J.-H. Increased Risk of Cirrhosis and Its Decompensation in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients With Newly Diagnosed Diabetes: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiang, J.C.; Gane, E.J.; Bai, W.W.; Gerred, S.J. Type 2 diabetes: A risk factor for liver mortality and complications in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazi, K.; Azhari, H.; Charette, J.H.; E. Underwood, F.; A. King, J.; Afshar, E.E.; Swain, M.G.; E. Congly, S.; Kaplan, G.G.; Shaheen, A.-A. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, M.R.; Wong, E.Y.T.; Wong, S.H.; Ng, A.W.T.; Loo, L.-H.; Chow, P.K.-H.; Ngeow, J. Global Epidemiology and Genetics of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 766–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrano, E.; Rinaldi, L.; Mormone, A.; Giorgione, C.; Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Nevola, R.; Marfella, R.; Sasso, F.C. Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), Type 2 Diabetes, and Non-viral Hepatocarcinoma: Pathophysiological Mechanisms and New Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plosker, G.L. Dapagliflozin: A Review of Its Use in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Drugs 2014, 74, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Zeeuw, D.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Law, G.; Desai, M.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, D.H.; Joo, S.K.; Koo, B.K.; Lim, S.; Lee, W.; Kim, W. Outcomes of Various Classes of Oral Antidiabetic Drugs on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.W.; Moon, H.-S.; Shin, H.; Han, H.; Park, S.; Cho, H.; Park, J.; Hur, M.H.; Park, M.K.; Won, S.-H.; et al. Inhibition of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 and liver-related complications in individuals with diabetes: A Mendelian randomization and population-based cohort study. Hepatology 2024, 80, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komiya, C.; Tsuchiya, K.; Shiba, K.; Miyachi, Y.; Furuke, S.; Shimazu, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kanno, K.; Ogawa, Y. Ipragliflozin Improves Hepatic Steatosis in Obese Mice and Liver Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetic Patients Irrespective of Body Weight Reduction. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehrehgosha, H.; Sohrabi, M.R.; Ismail-Beigi, F.; Malek, M.; Babaei, M.R.; Zamani, F.; Ajdarkosh, H.; Khoonsari, M.; Fallah, A.E.; Khamseh, M.E. Empagliflozin Improves Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-C.; Liu, C.-J. Chronic hepatitis B with concurrent metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: Challenges and perspectives. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Kessoku, T.; Kawanaka, M.; Nonaka, M.; Hyogo, H.; Fujii, H.; Nakajima, T.; Imajo, K.; Tanaka, K.; Kubotsu, Y.; et al. Ipragliflozin Improves the Hepatic Outcomes of Patients With Diabetes with NAFLD. Hepatol. Commun. 2021, 6, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Atsukawa, M.; Tsubota, A.; Mikami, S.; Haruki, U.; Yoshikata, K.; Ono, H.; Kawano, T.; Yoshida, Y.; Tanabe, T.; et al. Antifibrotic effect and long-term outcome of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with NAFLD complicated by diabetes mellitus. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 3073–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Mak, L.-Y.; Tang, E.H.-M.; Lui, D.T.-W.; Mak, J.H.-C.; Li, L.; Wu, T.; Chan, W.L.; Yuen, M.-F.; Lam, K.S.-L.; et al. SGLT2i reduces risk of developing HCC in patients with co-existing type 2 diabetes and hepatitis B infection: A territory-wide cohort study in Hong Kong. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, N.; Kitade, M.; Noguchi, R.; Namisaki, T.; Moriya, K.; Takeda, K.; Okura, Y.; Aihara, Y.; Douhara, A.; Kawaratani, H.; et al. Ipragliflozin, a sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, ameliorates the development of liver fibrosis in diabetic Otsuka Long–Evans Tokushima fatty rats. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.d.S.; Borges-Canha, M.; von Hafe, M.; Neves, J.S.; Vale, C.; Leite, A.R.; Carvalho, D.; Leite-Moreira, A. Effects of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors on liver parameters and steatosis: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2020, 37, e3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ropero, Á.; Vargas-Delgado, A.P.; Santos-Gallego, C.G.; Badimon, J.J. Inhibition of Sodium Glucose Cotransporters Improves Cardiac Performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Perco, P.; Mulder, S.; Leierer, J.; Hansen, M.K.; Heinzel, A.; Mayer, G. Canagliflozin reduces inflammation and fibrosis biomarkers: A potential mechanism of action for beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 1154–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mamun, A.; Akter, A.; Hossain, S.; Sarker, T.; Safa, S.A.; Mustafa, Q.G.; Muhammad, S.A.; Munir, F. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in liver disease. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 21, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Mu, K.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Zhao, W.; Huai, W.; Guo, P.; Han, L. Deregulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in hepatic parenchymal cells during liver cancer progression. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 94, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Yuan, X.; Liu, M.; Xue, B. miRNA-223-3p regulates NLRP3 to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation of hep3B cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 15, 2429–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazi, P.A.; DePinho, R.A. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: From genes to environment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.J.; Nguyen, V.H.; Yang, H.-I.; Li, J.; Le, M.H.; Wu, W.-J.; Han, N.X.; Fong, K.Y.; Chen, E.; Wong, C.; et al. Impact of fatty liver on long-term outcomes in chronic hepatitis B: A systematic review and matched analysis of individual patient data meta-analysis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkontchou, G.; Cosson, E.; Aout, M.; Mahmoudi, A.; Bourcier, V.; Charif, I.; Ganne-Carrie, N.; Grando-Lemaire, V.; Vicaut, E.; Trinchet, J.-C.; et al. Impact of Metformin on the Prognosis of Cirrhosis Induced by Viral Hepatitis C in Diabetic Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 2601–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, P.P.; Singh, A.G.; Murad, M.H.; Sanchez, W. Anti-Diabetic Medications and the Risk of Hepatocellular Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.-C.; Kuo, H.-T.; Hung, C.-H.; Tseng, K.-C.; Lai, H.-C.; Peng, C.-Y.; Wang, J.-H.; Chen, J.-J.; Lee, P.-L.; Chien, R.-N.; et al. Metformin reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence after successful antiviral therapy in patients with diabetes and chronic hepatitis C in Taiwan. J. Hepatol. 2022, 78, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, S.; Nomoto, K.; Suzuki, T.; Hayashi, S. Beneficial effect of omarigliptin on diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Kim, M.; Han, K.; Yoo, J.; Hwang, S.G.; Ahn, S.H. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality in chronic viral hepatitis with concurrent fatty liver. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 55, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barré, T.; Protopopescu, C.; Bani-Sadr, F.; Piroth, L.; Rojas, T.R.; Salmon-Ceron, D.; Wittkop, L.; Esterle, L.; Sogni, P.; Lacombe, K.; et al. Elevated Fatty Liver Index as a Risk Factor for All-Cause Mortality in Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Hepatitis C Virus–Coinfected Patients (ANRS CO13 HEPAVIH Cohort Study). Hepatology 2019, 71, 1182–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.W.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, B.K.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Han, K.-H.; Kim, S.U. Hepatic Steatosis Index in the Detection of Fatty Liver in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Receiving Antiviral Therapy. Gut Liver 2021, 15, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-SGLT2i Group n = 25,086 | SGLT2i Group ** n = 12,543 | ASMD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.2 (9.0) | 58.1 (9.2) | 0.016 |

| Male, n (%) | 15,374 (61.3) | 7687 (61.3) | 0 |

| Time to index date from entry of cohort (years), median (IQR) * | 1.9 (0.5–4.8) | 2.0 (0.3–4.9) | 0.009 |

| Time to index date from T2DM diagnosis (years), median (IQR) | 7.0 (3.1–10.4) | 7.3 (3.2–10.4) | 0.025 |

| Time to index date from CHB or CHC (years), median (IQR) | 4.3 (1.5–8.6) | 4.3 (1.7–8.5) | 0.019 |

| Chronic hepatitis B ¶ | 18,806 (75.0) | 9392 (74.9) | 0.002 |

| Chronic hepatitis C ¶ | 8553 (34.1) | 4300 (34.3) | 0.004 |

| Social economic status | <0.001 | ||

| Lower | 6596 (26.3) | 3286 (26.2) | |

| Middle | 7416 (29.6) | 3706 (29.5) | |

| High | 11,074 (44.1) | 5551 (44.3) | |

| Comorbidity †, n (%) | |||

| Fatty liver index, mean (SD) | 49.7 (25.6) | 51.2 (25.9) | 0.056 |

| MASLD | |||

| FLI ≥ 30 | 18,446 (73.5) | 9341 (74.5) | 0.021 |

| FLI ≥ 60 | 9343 (37.2) | 4981 (39.7) | 0.051 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1560 (6.2) | 706 (5.6) | 0.025 |

| Hypertension | 14,848 (59.2) | 7550 (60.2) | 0.020 |

| Dyslipidemia | 17,978 (71.7) | 8946 (71.3) | 0.008 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 5650 (22.5) | 2842 (22.7) | 0.003 |

| Concurrent drug treatment †, n (%) | |||

| Anti-viral medication for CHB or CHC | 2655 (10.6) | 1316 (10.5) | 0.003 |

| Anti-diabetic agents | |||

| Metformin | 20,741 (82.7) | 10,534 (84.0) | 0.035 |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 13,560 (54.1) | 7089 (56.5) | 0.050 |

| Sulfonylurea | 9299 (37.1) | 4761 (38.0) | 0.018 |

| TZD | 2342 (9.3) | 1220 (9.7) | 0.013 |

| GLP1 agonist | 108 (0.4) | 82 (0.7) | 0.030 |

| Insulins | 1009 (4.0) | 516 (4.1) | 0.005 |

| Antihypertensives | |||

| RAS inhibitor | 8362 (33.3) | 4312 (34.4) | 0.022 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 8910 (35.5) | 4589 (36.6) | 0.022 |

| β blocker | 3197 (12.7) | 1738 (13.9) | 0.033 |

| Diuretics | 4241 (16.9) | 2281 (18.2) | 0.034 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | |||

| Statins | 16,469 (65.7) | 8267 (65.9) | 0.006 |

| Others | 7103 (28.3) | 3516 (28.0) | 0.006 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 7703 (30.7) | 3961 (31.6) | 0.019 |

| Anticoagulant agents | 693 (2.8) | 341 (2.7) | 0.003 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.029 | ||

| never | 13,244 (52.8) | 6568 (52.4) | |

| former | 8037 (32.0) | 4002 (31.9) | |

| current | 3805 (15.2) | 1973 (15.7) | |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| never | 12,332 (49.2) | 6201 (49.4) | |

| ≤2 times/week | 6355 (25.3) | 3149 (25.1) | |

| ≥3 times/week | 6399 (25.5) | 3193 (25.5) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | 0.029 | ||

| never | 10,227 (40.8) | 5184 (41.3) | |

| ≤2 times/week | 4335 (17.3) | 2064 (16.5) | |

| ≥3 times/week | 10,524 (42.0) | 5295 (42.2) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.3 (3.3) | 26.7 (3.4) | 0.106 |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD) | 88.1 (8.7) | 88.8 (8.9) | 0.082 |

| Total cholesterol, (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 183.1 (44.2) | 181.3 (45.9) | 0.040 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 102.0 (41.1) | 100.2 (40.3) | 0.042 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 50.1 (12.9) | 49.8 (12.7) | 0.020 |

| TG-C (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 134 (94–194) | 132 (94–191) | 0.015 |

| SBP, mean (SD) | 128.0 (14.4) | 128.3 (14.8) | 0.015 |

| DBP, mean (SD) | 78.6 (9.8) | 78.7 (10.0) | 0.009 |

| FBS (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 145.6 (49.0) | 144.8 (44.4) | 0.018 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 0.88 (0.26) | 0.87 (0.24) | 0.017 |

| AST, mean (SD) | 39.0 (40.6) | 38.8 (30.5) | 0.006 |

| ALT, mean (SD) | 43.9 (53.5) | 43.8 (36.9) | 0.002 |

| γ-GTP, mean (SD) | 66.4 (87.8) | 65.0 (85.3) | 0.016 |

| No. of Events (IR per 1000 PY) | Subdistribution Hazard Ratio * (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite liver-related complications | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group (n = 25,086) | 772 (8.99) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group (n = 12,543) | 291 (6.67) | 0.74 (0.65–0.85) | <0.001 |

| HCC | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group | 515 (5.96) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group | 202 (4.61) | 0.77 (0.66–0.91) | 0.002 |

| Cirrhosis-related complication | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group | 358 (4.13) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group | 115 (2.61) | 0.64 (0.52–0.79) | <0.001 |

| Liver transplant | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group | 60 (0.69) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group | 13 (0.29) | 0.44 (0.24–0.81) | 0.008 |

| Liver-related mortality | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group | 197 (2.23) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group | 57 (1.29) | 0.67 (0.50–0.91) | 0.010 |

| No. of Events (IR per 1000 PY) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New-onset liver cirrhosis in patients without previous LC history | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group (n = 23,526) | 320 (3.96) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group (n = 11,837) | 110 (2.66) | 0.67 (0.54–0.83) * | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality | |||

| Non-SGLT 2i group (n = 25,086) | 695 (7.88) | 1 (Reference) | |

| SGLT 2i group (n = 12,543) | 256 (5.79) | 0.76 (0.65–0.88) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, S.H.; Choi, J.; Yim, H.J.; Jung, Y.K.; Yim, S.Y.; Lee, Y.-S.; Seo, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Yeon, J.E.; Byun, K.S. Association Between SGLT2 Inhibitor Use and Reduced Risk of Liver-Related Events, Including Hepatocellular Carcinoma, in Diabetic Patients with Viral Hepatitis: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010120

Kang SH, Choi J, Yim HJ, Jung YK, Yim SY, Lee Y-S, Seo YS, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Byun KS. Association Between SGLT2 Inhibitor Use and Reduced Risk of Liver-Related Events, Including Hepatocellular Carcinoma, in Diabetic Patients with Viral Hepatitis: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Seong Hee, Jimi Choi, Hyung Joon Yim, Young Kul Jung, Sun Young Yim, Young-Sun Lee, Yeon Seok Seo, Ji Hoon Kim, Jong Eun Yeon, and Kwan Soo Byun. 2026. "Association Between SGLT2 Inhibitor Use and Reduced Risk of Liver-Related Events, Including Hepatocellular Carcinoma, in Diabetic Patients with Viral Hepatitis: A Nationwide Cohort Study" Cancers 18, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010120

APA StyleKang, S. H., Choi, J., Yim, H. J., Jung, Y. K., Yim, S. Y., Lee, Y.-S., Seo, Y. S., Kim, J. H., Yeon, J. E., & Byun, K. S. (2026). Association Between SGLT2 Inhibitor Use and Reduced Risk of Liver-Related Events, Including Hepatocellular Carcinoma, in Diabetic Patients with Viral Hepatitis: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancers, 18(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010120