A TabNet-Based Multidimensional Deep Learning Model for Predicting Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Diagnostic Criteria for DIC

2.3. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.4. TabNet Architecture

2.5. Model Development

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Model Parameters

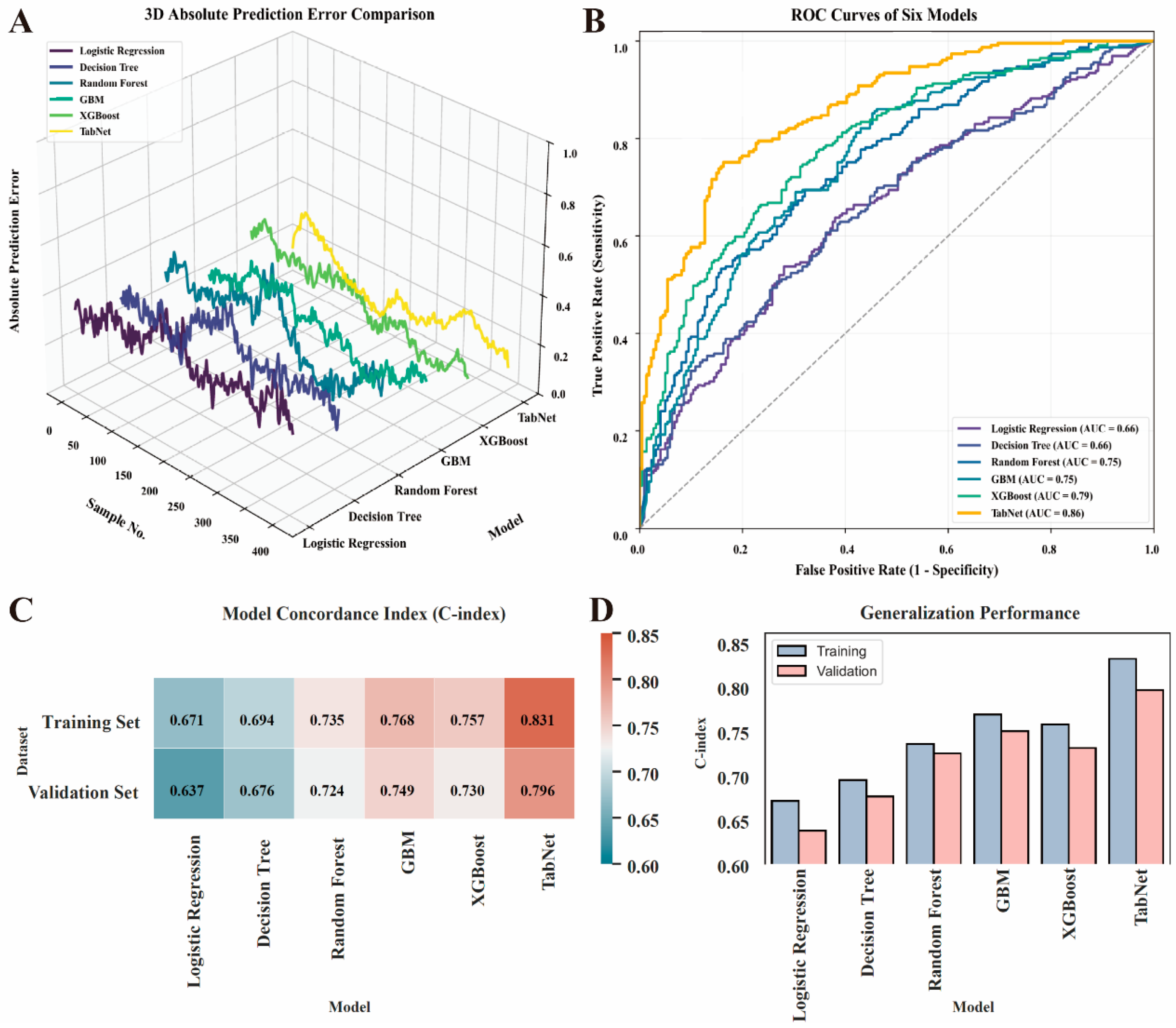

3.3. Model Development and Performance Evaluation

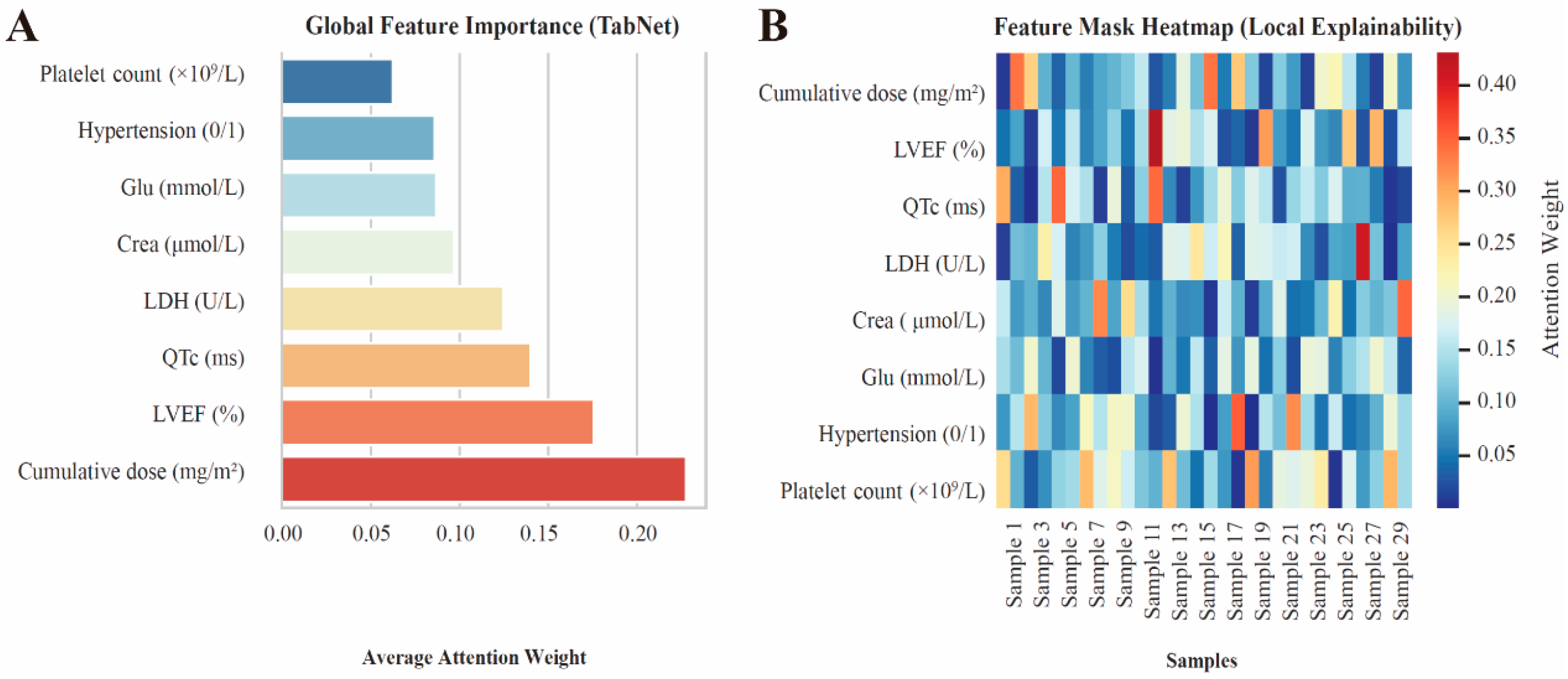

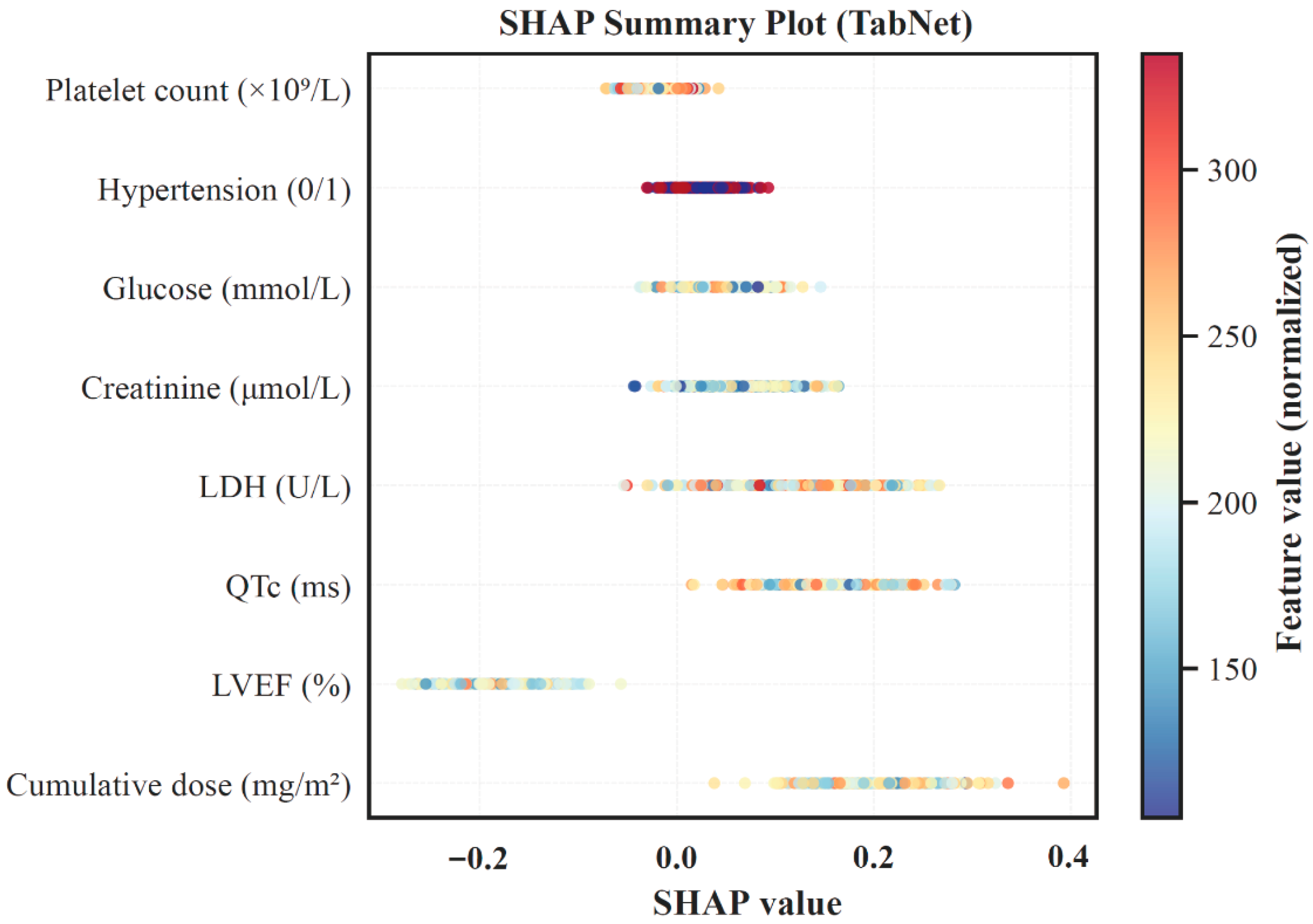

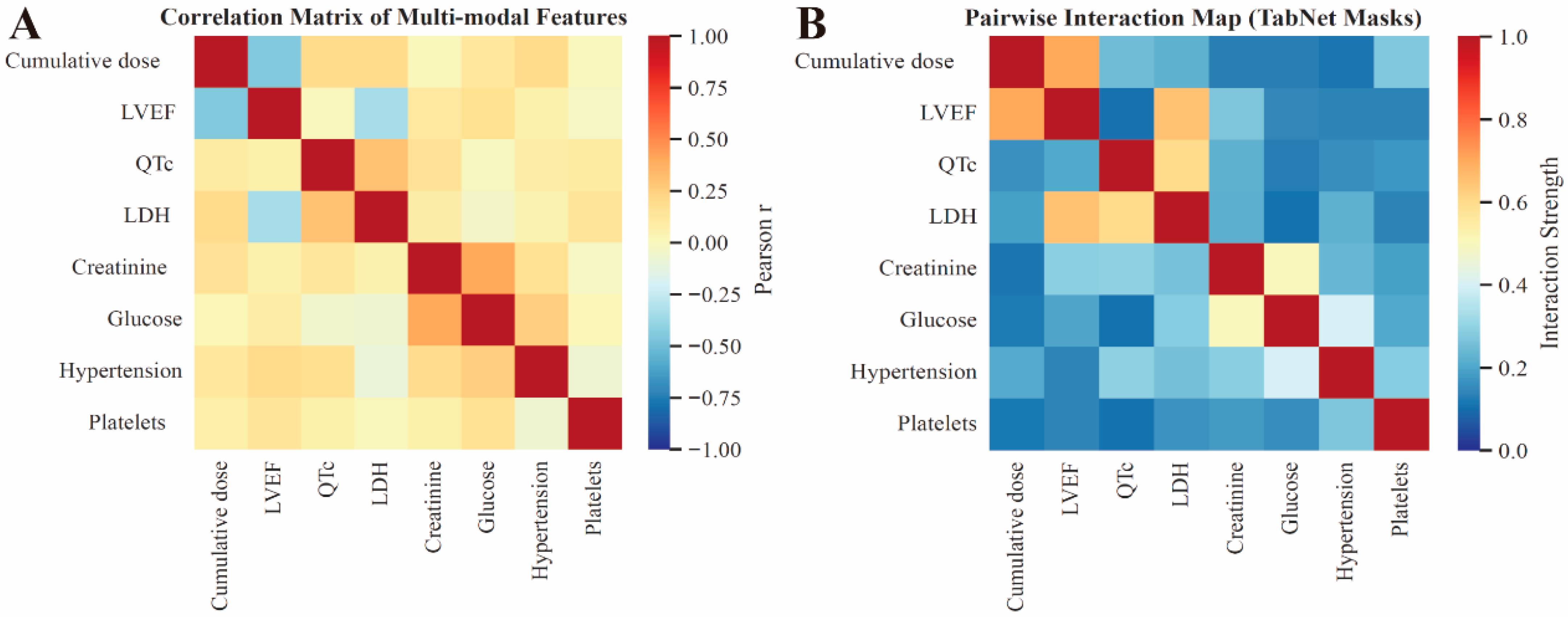

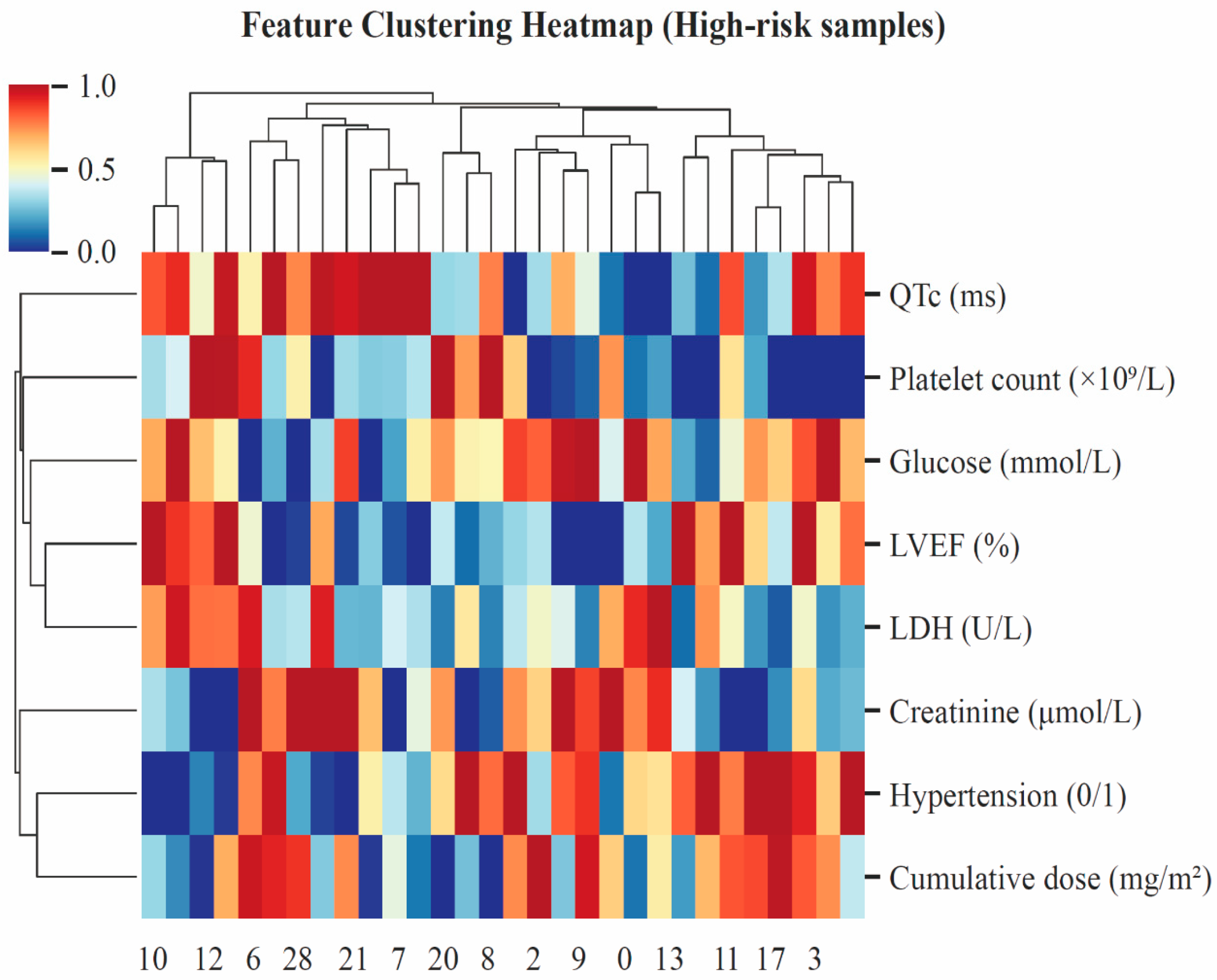

3.4. Model Interpretation

3.5. Model Performance and Clinical Utility Evaluation

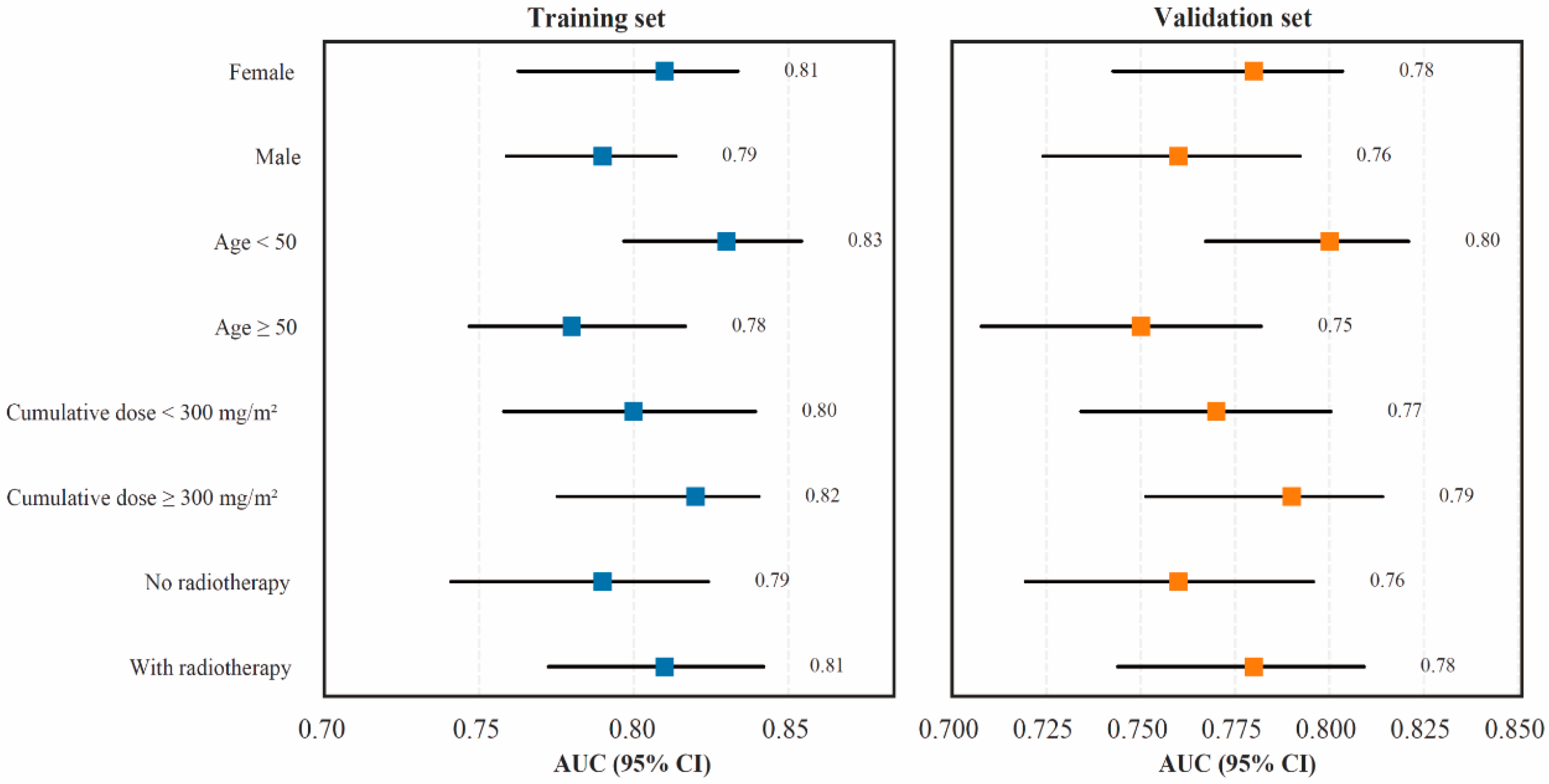

3.6. Subgroup and Stratified Validation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full term |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| Adam | Adaptive moment estimation |

| A/G | Albumin-to-globulin ratio |

| ALB | Albumin |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AP | Average precision |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| BASO | Basophils |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CREA | Creatinine |

| C-index | Concordance index |

| DBIL | Direct bilirubin |

| DCA | Decision curve analysis |

| DIC | Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity |

| DT | Decision tree |

| EOS | Eosinophils |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| GBM | Gradient boosting machines |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| GLB | Globulin |

| GLS | Global longitudinal strain |

| GLU | Glucose |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| Hct | Hematocrit |

| hs-cTnI/T | High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I/T |

| IDBIL | Indirect bilirubin |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| KNN | k-nearest neighbor |

| LA | Left atrial |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LR | Logistic regression |

| LVEDD | Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LYM | Lymphocytes |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MON | Monocytes |

| NEU | Neutrophils |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PALB | Prealbumin |

| PLT | Platelet count |

| PT | Prothrombin time |

| QTc | Corrected QT interval |

| QRS | QRS complex duration |

| RBC | Red blood cell count |

| RF | Random forest |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SMOTE | Synthetic minority oversampling technique |

| TabNet | Tabular Neural Network |

| TBIL | Total bilirubin |

| TNM | Tumor–Node–Metastasis staging system |

| TP | Total protein |

| UA | Uric acid |

| WBC | White blood cell count |

| XGBoost | Extreme gradient boosting |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heater, N.K.; Warrior, S.; Lu, J. Current and future immunotherapy for breast cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zheng, L.W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Cai, Y.W.; Wang, L.P.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.C.; Shao, Z.M.; Yu, K.D. Breast cancer: Pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Gielecińska, A.; Mujwar, S.; Kołat, D.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Celik, I.; Kontek, R. Doxorubicin-An Agent with Multiple Mechanisms of Anticancer Activity. Cells 2023, 12, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mattioli, R.; Ilari, A.; Colotti, B.; Mosca, L.; Fazi, F.; Colotti, G. Doxorubicin and other anthracyclines in cancers: Activity, chemoresistance and its overcoming. Mol. Aspects Med. 2023, 93, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, A.; Avinash, D.; Sahu, K.K.; Patel, P.; Gupta, G.D.; Kurmi, B.D. A comprehensive review on doxorubicin: Mechanisms, toxicity, clinical trials, combination therapies and nanoformulations in breast cancer. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 102–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, S.; Ljubojevic-Holzer, S. CD8+ T cells as the missing link between doxorubicin cancer therapy and heart failure risk. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 890–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Zou, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Weng, X.; Pei, Z.; Song, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Z.; Gao, R.; et al. Critical Role of the cGAS-STING Pathway in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, e223–e242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.Y.; Guo, Z.; Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.P.; Teng, T.; Yan, L.; Tang, Q.Z. Underlying the Mechanisms of Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity: Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilli, M.; Cipolla, C.M.; Dent, S.; Minotti, G.; Cardinale, D.M. Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity in Adult Cancer Patients: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2024, 6, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bloom, M.W.; Vo, J.B.; Rodgers, J.E.; Ferrari, A.M.; Nohria, A.; Deswal, A.; Cheng, R.K.; Kittleson, M.M.; Upshaw, J.N.; Palaskas, N.; et al. Cardio-Oncology and Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2025, 31, 415–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vancheri, F.; Longo, G.; Henein, M.Y. Left ventricular ejection fraction: Clinical, pathophysiological, and technical limitations. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1340708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Travers, S.; Alexandre, J.; Baldassarre, L.A.; Salem, J.E.; Mirabel, M. Diagnosis of cancer therapy-related cardiovascular toxicities: A multimodality integrative approach and future developments. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 118, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y.; Hong, G.; Ning, W. Construction of machine learning diagnostic models for cardiovascular pan-disease based on blood routine and biochemical detection data. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dincer, S.; Akmansu, M.; Akyol, O. Machine learning modeling of cancer treatment-related cardiac events in breast cancer: Utilizing dosiomics and radiomics. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1557382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- An, D.; Ibrahim, E.S. Elucidating Early Radiation-Induced Cardiotoxicity Markers in Preclinical Genetic Models Through Advanced Machine Learning and Cardiac MRI. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, C.; Chen, L.; Chou, C.; Ngorsuraches, S.; Qian, J. Using Machine Learning Approaches to Predict Short-Term Risk of Cardiotoxicity Among Patients with Colorectal Cancer After Starting Fluoropyrimidine-Based Chemotherapy. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2022, 22, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C. Stop Explaining Black Box Machine Learning Models for High Stakes Decisions and Use Interpretable Models Instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ravera, F.; Gilardi, N.; Ballestrero, A.; Zoppoli, G. Applications, challenges and future directions of artificial intelligence in cardio-oncology. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 55, e14370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y. Deep learning-assisted high-content screening identifies isoliquiritigenin as an inhibitor of DNA double-strand breaks for preventing doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Biol. Direct 2023, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kita, K.; Fujimori, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Kanie, Y.; Takenaka, S.; Kaito, T.; Taki, T.; Ukon, Y.; Furuya, M.; Saiwai, H.; et al. Bimodal artificial intelligence using TabNet for differentiating spinal cord tumors-Integration of patient background information and images. iScience 2023, 26, 107900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qi, H.; Hu, Y.; Fan, R.; Deng, L. Tab-Cox: An Interpretable Deep Survival Analysis Model for Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Based on TabNet. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 4937–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.N.H.; Reaz, M.B.I.; Ali, S.H.M.; Crespo, M.L.; Ahmad, S.; Salim, G.M.; Haque, F.; Ordóñez, L.G.G.; Islam, M.J.; Mahdee, T.M.; et al. Deep learning for early detection of chronic kidney disease stages in diabetes patients: A TabNet approach. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 166, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito-Hagiwara, K.; Hagiwara, J.; Endo, Y.; Becker, L.B.; Hayashida, K. Cardioprotective strategies against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: A review from standard therapies to emerging mitochondrial transplantation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 189, 118315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, S.; Dai, Y. Research progress of therapeutic drugs for doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J. Mitochondrial quality control mechanisms as therapeutic targets in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, P.S.; Jaiswal, A.; Khurana, A.; Bhatti, J.S.; Navik, U. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: An update on the molecular mechanism and novel therapeutic strategies for effective management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Cai, J.; Chen, L.; Cheng, H.; Song, X.; Xue, J.; Xu, R.; Ma, J.; Ge, J. AIG1 protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by promoting ubiquitination-mediated p53 degradation. Theranostics 2025, 15, 4931–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; Qiu, R.; Zhao, C.; Chen, B.; Shang, H. Optimizing dose selection for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in mice: A comprehensive analysis of single and multiple-dose regimens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1003, 177883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Bakhtyar, M.; Jun, S.R.; Boerma, M.; Lan, R.S.; Su, L.J.; Makhoul, S.; Hsu, P.C. A narrative review of metabolomics approaches in identifying biomarkers of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Metabolomics 2025, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, C.; Pei, J.; Li, D.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, R.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Lian, Z.; et al. Analysis and Validation of Critical Signatures and Immune Cell Infiltration Characteristics in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Integrating Bioinformatics and Machine Learning. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Araújo, D.C.; Simões, R.; Sabino, A.P.; Oliveira, A.N.; Oliveira, C.M.; Veloso, A.A.; Gomes, K.B. Predicting doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in breast cancer: Leveraging machine learning with synthetic data. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2025, 63, 1535–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Kang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Qi, K.; Wu, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y. Use of Deep-Learning Assisted Assessment of Cardiac Parameters in Zebrafish to Discover Cyanidin Chloride as a Novel Keap1 Inhibitor Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2301136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grafton, F.; Ho, J.; Ranjbarvaziri, S.; Farshidfar, F.; Budan, A.; Steltzer, S.; Maddah, M.; Loewke, K.E.; Green, K.; Patel, S.; et al. Deep learning detects cardiotoxicity in a high-content screen with induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. eLife 2021, 10, e68714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saleh, Y.; Abdelkarim, O.; Herzallah, K.; Abela, G.S. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: Mechanisms of action, incidence, risk factors, prevention, and treatment. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puppe, J.; van Ooyen, D.; Neise, J.; Thangarajah, F.; Eichler, C.; Krämer, S.; Pfister, R.; Mallmann, P.; Wirtz, M.; Michels, G. Evaluation of QTc Interval Prolongation in Breast Cancer Patients after Treatment with Epirubicin, Cyclophosphamide, and Docetaxel and the Influence of Interobserver Variation. Breast Care 2017, 12, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, X.; Weng, Y.; Jiang, T.; Ou, W.; Zhang, N.; Dong, Q.; Tang, X. Influencing factors of anthracycline-induced subclinical cardiotoxicity in acute leukemia patients. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Boriani, G.; Cardinale, D.; Cordoba, R.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4229–4361, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1621. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad196. PMID: 36017568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Yang, P. The mechanism and therapeutic strategies in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: Role of programmed cell death. Cell Stress Chaperones 2024, 29, 666–680, Erratum in Cell Stress Chaperones 2024, 29, 720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstres.2024.10.005. PMID: 39343295; PMCID: PMC11490929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano, G.M.C.; Teerlink, J.R.; Kinugawa, K.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Chioncel, O.; Fang, J.; Greenberg, B.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Imamura, T.; Inomata, T.; et al. The use of left ventricular ejection fraction in the diagnosis and management of heart failure. A clinical consensus statement of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC, the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA), and the Japanese Heart Failure Society (JHFS). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 27, 1174–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinale, D.; Iacopo, F.; Cipolla, C.M. Cardiotoxicity of Anthracyclines. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraud, E.L.; Ferrier, K.R.M.; Lankheet, N.A.G.; Desar, I.M.E.; Steeghs, N.; Beukema, R.J.; van Erp, N.P.; Smolders, E.J. The QT interval prolongation potential of anticancer and supportive drugs: A comprehensive overview. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e406–e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.R.; Parish, P.C.; Tan, X.; Fabricio, J.; Andreini, C.L.; Hicks, C.H.; Jensen, B.C.; Muluneh, B.; Zeidner, J.F. Association of QTc Formula With the Clinical Management of Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- She, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, G.; Du, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Dexmedetomidine Ameliorates Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting MDH2 Lactylation via Regulating Metabolic Reprogramming. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2409499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kalkhoran, S.B.; Basalay, M.; He, Z.; Golforoush, P.; Roper, T.; Caplin, B.; Salama, A.D.; Davidson, S.M.; Yellon, D.M. Investigating the cause of cardiovascular dysfunction in chronic kidney disease: Capillary rarefaction and inflammation may contribute to detrimental cardiovascular outcomes. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 119, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- An, Y.; Geng, K.; Wang, H.Y.; Wan, S.R.; Ma, X.M.; Long, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z.Z. Hyperglycemia-induced STING signaling activation leads to aortic endothelial injury in diabetes. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szukiewicz, D. Molecular Mechanisms for the Vicious Cycle between Insulin Resistance and the Inflammatory Response in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gallo, G.; Savoia, C. Hypertension and Heart Failure: From Pathophysiology to Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tefferi, A.; Gangat, N.; Loscocco, G.G.; Guglielmelli, P.; Szuber, N.; Pardanani, A.; Orazi, A.; Barbui, T.; Vannucchi, A.M. Essential Thrombocythemia: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|---|

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) | ≥10% absolute reduction from baseline to <53% or ≥5% reduction to <53% with symptoms or signs of heart failure. |

| Global longitudinal strain (GLS) | >15% relative reduction from baseline, indicating subclinical myocardial injury. |

| Cardiac biomarkers | Persistent elevation of hs-cTnI/T or NT-proBNP above the upper reference limit, or a 1.5- to 2-fold increase from baseline. |

| Clinical manifestations | New or worsening symptoms of heart failure, such as dyspnea, fatigue, or peripheral edema. |

| Total | DIC | Non-DIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n = 2034 | n = 305 | 1729 | p |

| Age (years) | 54.8 ± 10.5 | 59.1 ± 9.7 | 53.9 ± 10.4 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 3.4 | 25.4 ± 3.5 | 24.8 ± 3.4 | 0.068 |

| Hypertension (%) | 41.6 | 59 | 38.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 41.60% | 59.00% | 38.30% | |

| No | 58.40% | 41.00% | 61.70% | |

| Diabetes (%) | 20.5 | 30.8 | 18.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 20.50% | 30.80% | 18.70% | |

| No | 79.50% | 69.20% | 81.30% | |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 9.6 | 14.8 | 8.6 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 9.60% | 14.80% | 8.60% | |

| No | 90.40% | 85.20% | 91.40% | |

| TNM stage | 0.030 | |||

| Stage I | 18.50% | 12.00% | 19.70% | |

| Stage II | 37.30% | 38.50% | 37.00% | |

| Stage III | 31.00% | 34.00% | 30.40% | |

| Stage IV | 13.20% | 15.50% | 12.90% | |

| Cumulative dose (mg/m2) | 278 ± 55 | 311 ± 49 | 272 ± 53 | <0.001 |

| Chest radiotherapy | 0.007 | |||

| Yes | 22.70% | 29.60% | 21.40% | |

| No | 77.30% | 70.40% | 78.60% | |

| HER2-targeted therapy | 0.009 | |||

| Yes | 12.50% | 18.00% | 11.40% | |

| No | 87.50% | 82.00% | 88.60% |

| Training Set | Validation Set | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n = 1627 | n = 407 | p |

| Age (years) | 55.0 ± 10.3 | 54.6 ± 10.8 | 0.472 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 3.4 | 25.0 ± 3.5 | 0.682 |

| Hypertension (%) | 41.8 | 40.7 | 0.613 |

| Yes | 41.80% | 40.70% | |

| No | 58.20% | 59.30% | |

| Diabetes (%) | 20.3 | 21 | 0.745 |

| Yes | 20.30% | 21.00% | |

| No | 79.70% | 79.00% | |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 9.5 | 10.1 | 0.699 |

| Yes | 9.50% | 10.10% | |

| No | 90.50% | 89.90% | |

| TNM stage | 0.511 | ||

| Stage I | 18.30% | 19.20% | |

| Stage II | 37.50% | 36.80% | |

| Stage III | 31.20% | 30.40% | |

| Stage IV | 13.00% | 13.60% | |

| Cumulative dose (mg/m2) | 279 ± 54 | 277 ± 56 | 0.594 |

| Chest radiotherapy (%) | 22.5 | 23.1 | 0.808 |

| Yes | 22.50% | 23.10% | |

| No | 77.50% | 76.90% | |

| HER2-targeted therapy (%) | 12.6 | 11.8 | 0.671 |

| Yes | 12.60% | 11.80% | |

| No | 87.40% | 88.20% | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 126 ± 15 | 127 ± 14 | 0.513 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78 ± 9 | 77 ± 9 | 0.42 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 76 ± 11 | 75 ± 10 | 0.286 |

| QTc (ms) | 423 ± 26 | 424 ± 25 | 0.661 |

| QRS duration (ms) | 93 ± 12 | 92 ± 13 | 0.338 |

| LVEF (%) | 62.7 ± 6.6 | 62.9 ± 6.8 | 0.764 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 48.4 ± 4.8 | 48.3 ± 4.9 | 0.837 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 36.9 ± 4.2 | 36.7 ± 4.3 | 0.541 |

| E/A ratio | 1.03 ± 0.28 | 1.04 ± 0.27 | 0.678 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25 [19–32] | 25 [18–31] | 0.729 |

| AST (U/L) | 24 [19–30] | 24 [19–29] | 0.842 |

| GGT (U/L) | 28 [20–39] | 27 [20–38] | 0.504 |

| LDH (U/L) | 211 ± 61 | 210 ± 60 | 0.812 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 12.0 [9.0–15.0] | 12.1 [9.2–15.3] | 0.905 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 3.6 [2.8–4.6] | 3.6 [2.9–4.7] | 0.772 |

| IDBIL (μmol/L) | 8.3 [6.3–10.5] | 8.3 [6.4–10.6] | 0.931 |

| TP (g/L) | 69.8 ± 5.1 | 69.9 ± 5.2 | 0.876 |

| ALB (g/L) | 41.6 ± 3.8 | 41.8 ± 3.7 | 0.521 |

| GLB (g/L) | 28.2 ± 3.1 | 28.3 ± 3.0 | 0.729 |

| A/G | 1.47 ± 0.22 | 1.48 ± 0.22 | 0.463 |

| PALB (mg/L) | 230 [190–270] | 231 [192–272] | 0.833 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 0.952 |

| CREA (μmol/L) | 73.6 ± 14.1 | 73.2 ± 13.9 | 0.74 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 341 ± 89 | 339 ± 90 | 0.678 |

| ALP (U/L) | 85 ± 28 | 84 ± 27 | 0.563 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 5.64 ± 1.09 | 5.61 ± 1.08 | 0.744 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 0.498 |

| NEU (%) | 61 ± 9 | 61 ± 9 | 0.882 |

| LYM (%) | 28 ± 8 | 28 ± 8 | 0.97 |

| MON (%) | 7.1 ± 2.0 | 7.0 ± 2.0 | 0.512 |

| EOS (%) | 2.2 [1.4–3.1] | 2.2 [1.5–3.0] | 0.789 |

| BASO (%) | 0.5 [0.4–0.6] | 0.5 [0.4–0.6] | 0.946 |

| Hb (g/L) | 129 ± 14 | 129 ± 13 | 0.944 |

| RBC (×1012/L) | 4.32 ± 0.48 | 4.33 ± 0.47 | 0.807 |

| Hct (L/L) | 0.390 ± 0.040 | 0.391 ± 0.041 | 0.835 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 238 ± 62 | 239 ± 63 | 0.884 |

| PT (s) | 12.8 ± 2.2 | 12.9 ± 2.2 | 0.714 |

| D-dimer (mg/L FEU) | 0.32 [0.21–0.51] | 0.32 [0.20–0.50] | 0.921 |

| Model | MAE | RMSE | R2 | Stability (σ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.386 | 0.472 | 0.58 | 0.091 |

| Decision Tree | 0.334 | 0.419 | 0.63 | 0.085 |

| Random Forest | 0.326 | 0.401 | 0.68 | 0.076 |

| GBM | 0.24 | 0.315 | 0.74 | 0.062 |

| XGBoost | 0.246 | 0.308 | 0.75 | 0.059 |

| TabNet | 0.175 | 0.231 | 0.83 | 0.047 |

| Model | AUC | 95% CI | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 0.66 | 0.62–0.70 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.32 |

| Decision Tree | 0.66 | 0.61–0.71 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.30 |

| Random Forest | 0.75 | 0.71–0.79 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.50 |

| GBM | 0.75 | 0.70–0.79 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| XGBoost | 0.79 | 0.75–0.83 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.56 |

| TabNet | 0.86 | 0.82–0.90 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, J.; Hong, X.; Dong, L.; Jiang, W.; Yang, W. A TabNet-Based Multidimensional Deep Learning Model for Predicting Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers 2026, 18, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010117

Cao J, Hong X, Dong L, Jiang W, Yang W. A TabNet-Based Multidimensional Deep Learning Model for Predicting Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Juanwen, Xiaojian Hong, Li Dong, Wei Jiang, and Wei Yang. 2026. "A TabNet-Based Multidimensional Deep Learning Model for Predicting Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients" Cancers 18, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010117

APA StyleCao, J., Hong, X., Dong, L., Jiang, W., & Yang, W. (2026). A TabNet-Based Multidimensional Deep Learning Model for Predicting Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers, 18(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010117