Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α, a Novel Molecular Target for a 2-Aminopyrrole Derivative: Biological and Molecular Modeling Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

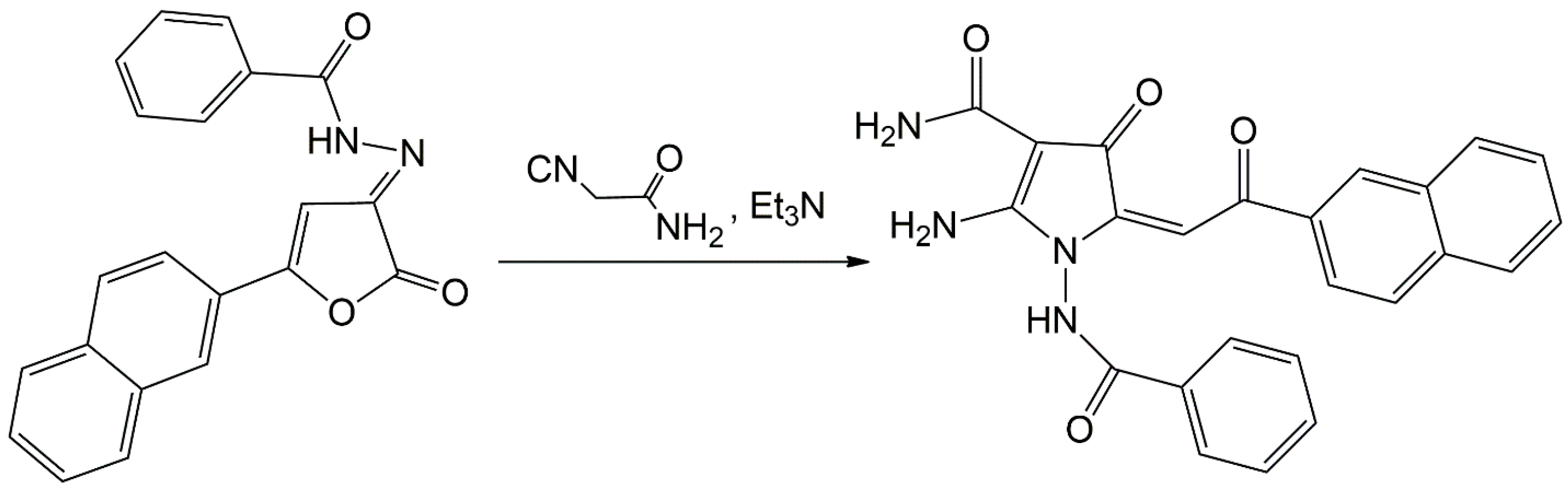

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.3. Real-Time Monitoring of Cell Proliferation

2.4. Antibodies

2.5. Western Blotting

2.6. RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

2.7. In Vivo Study of Antitumor Activity

2.8. Statistics

2.9. HIF-1α Modeling

2.10. HIF-1 Protein Complex Modeling

2.11. Site Mapping and Docking

3. Results

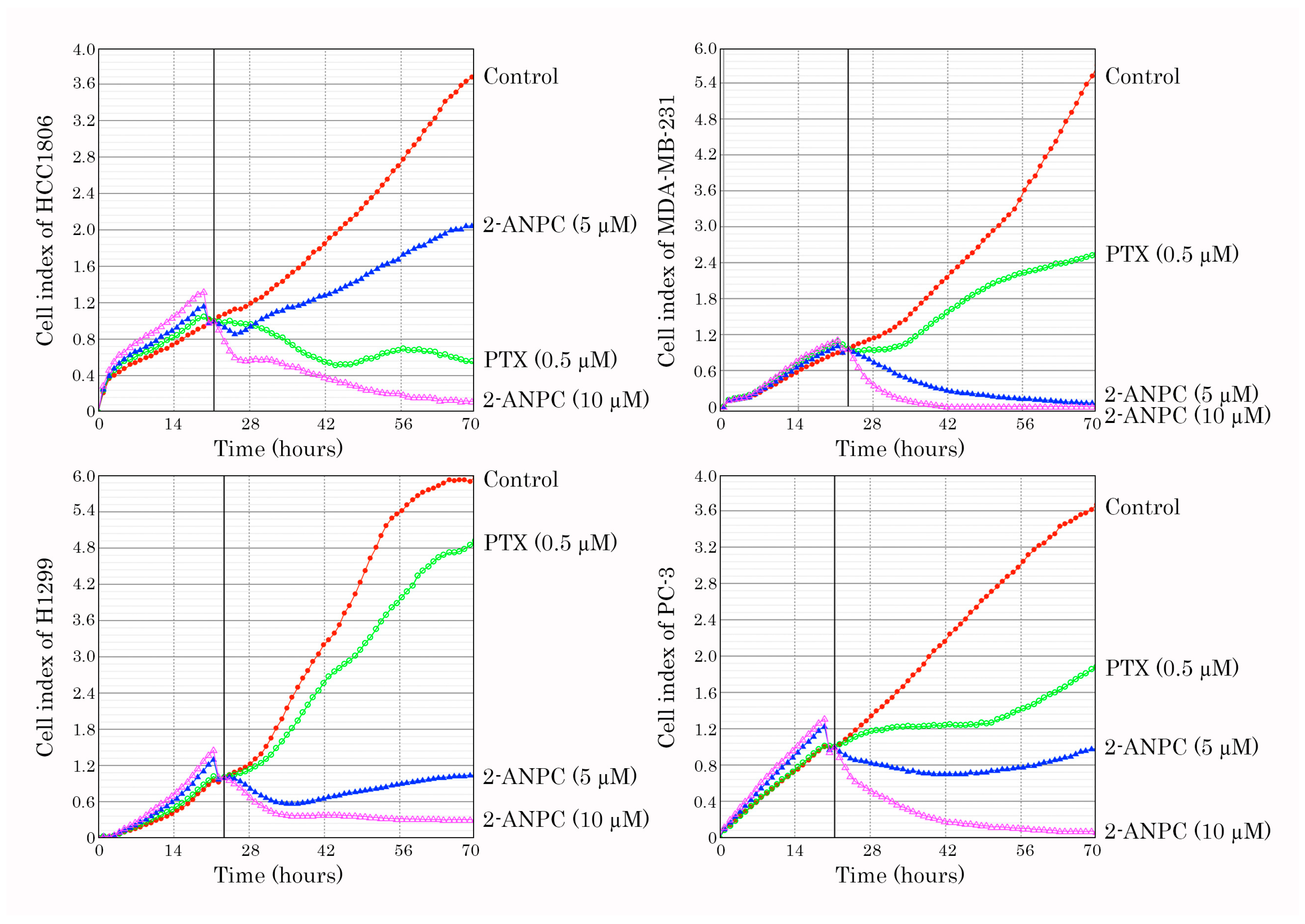

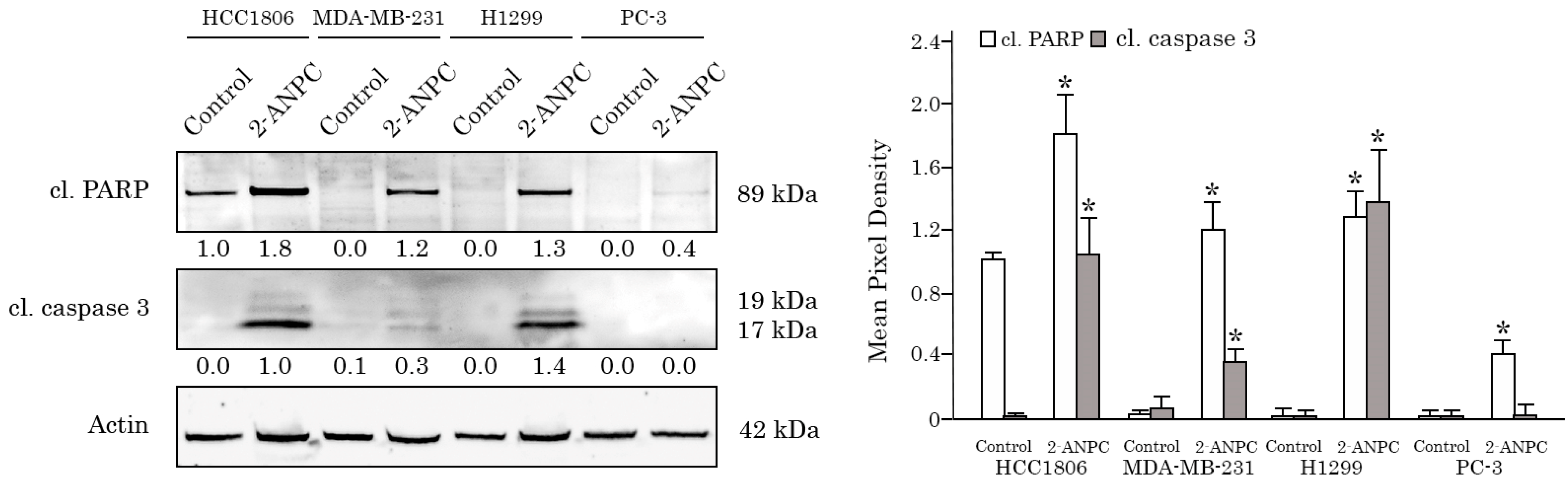

3.1. 2-ANPC Exhibits Potent Anti-Proliferative and Pro-Apoptotic Activities Against Breast, Lung, and Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

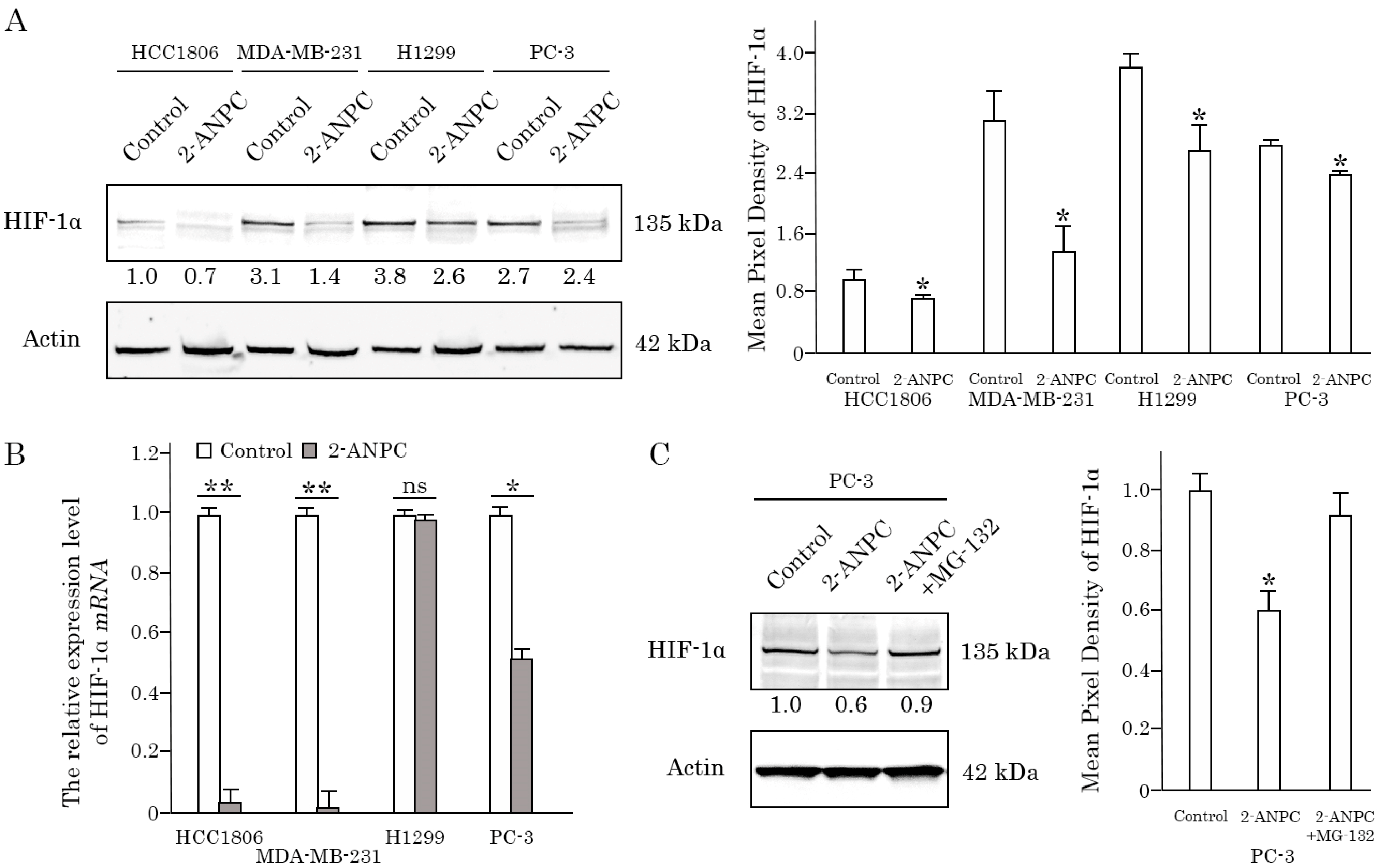

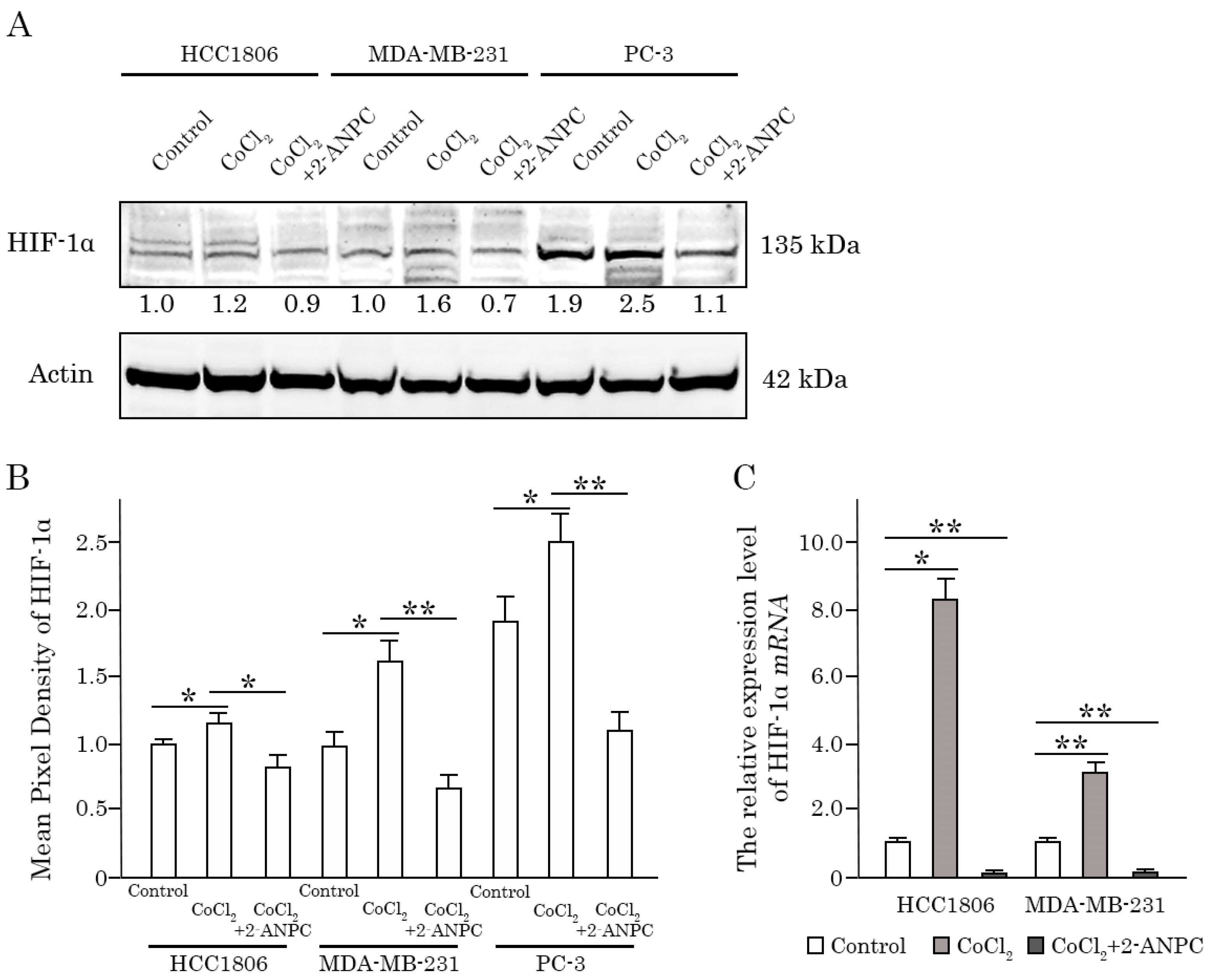

3.2. 2-ANPC Effectively Decreases HIF-1α Expression In Vitro in Epithelial Cancer Cells by Promoting Its Proteasome-Dependent Degradation

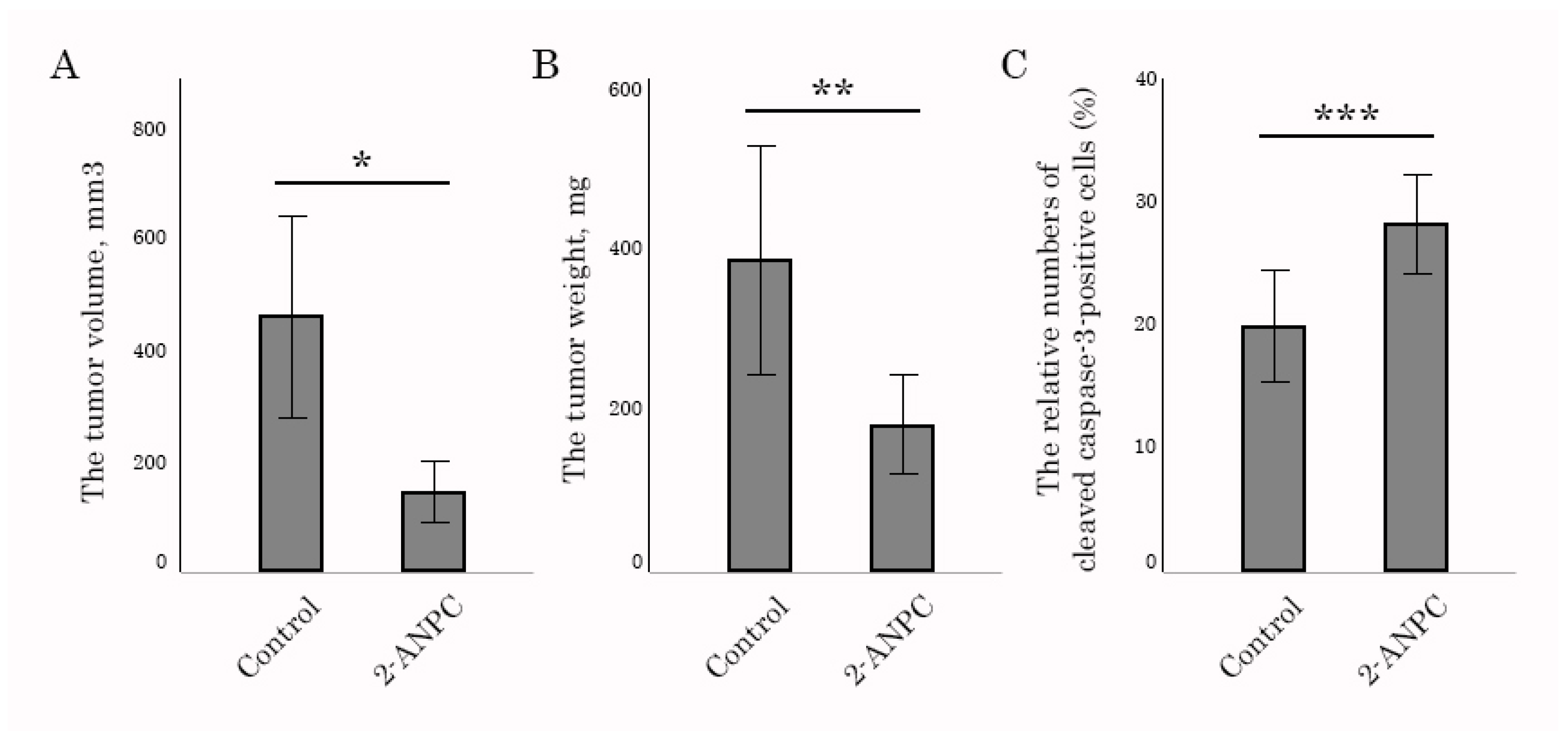

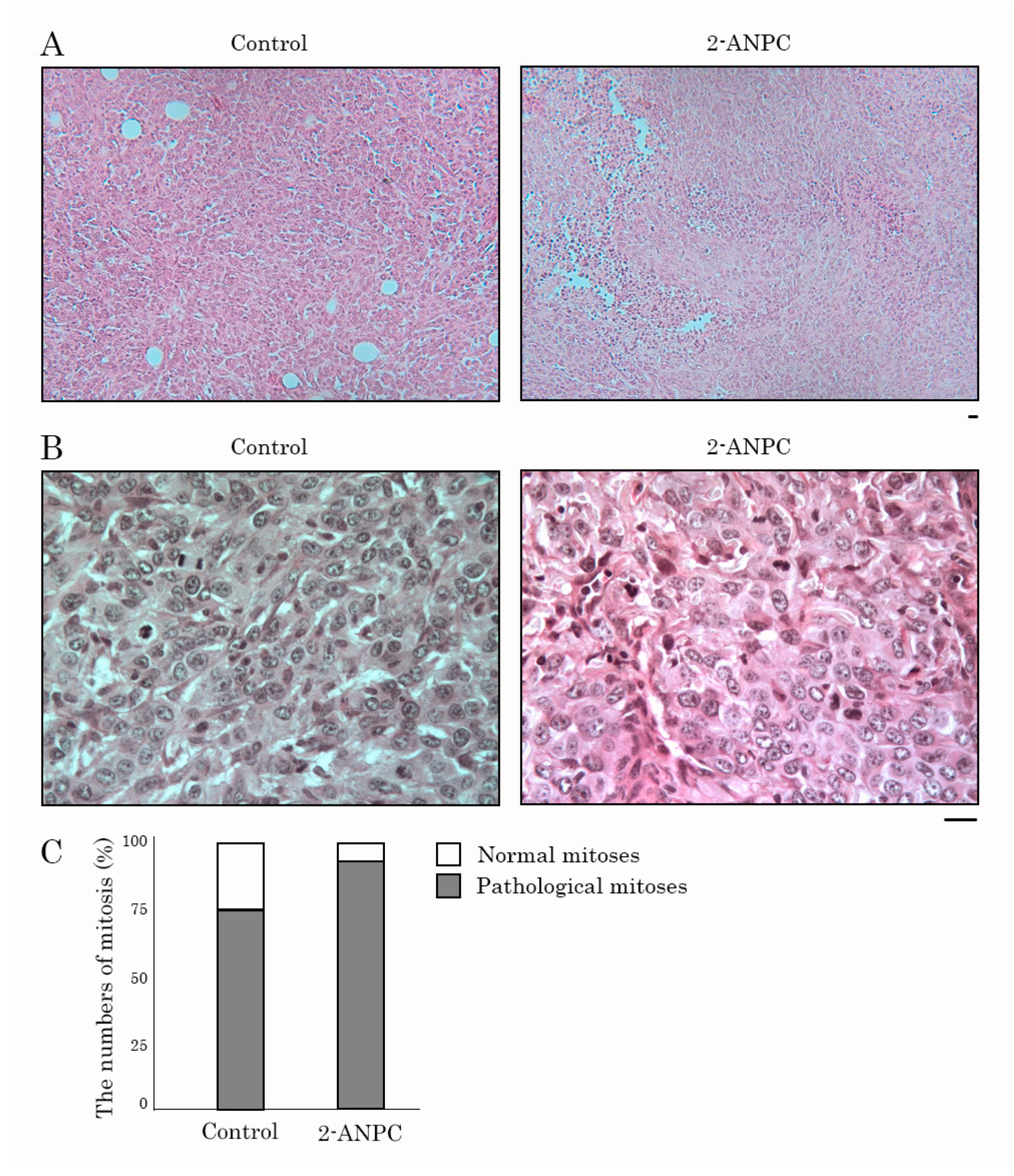

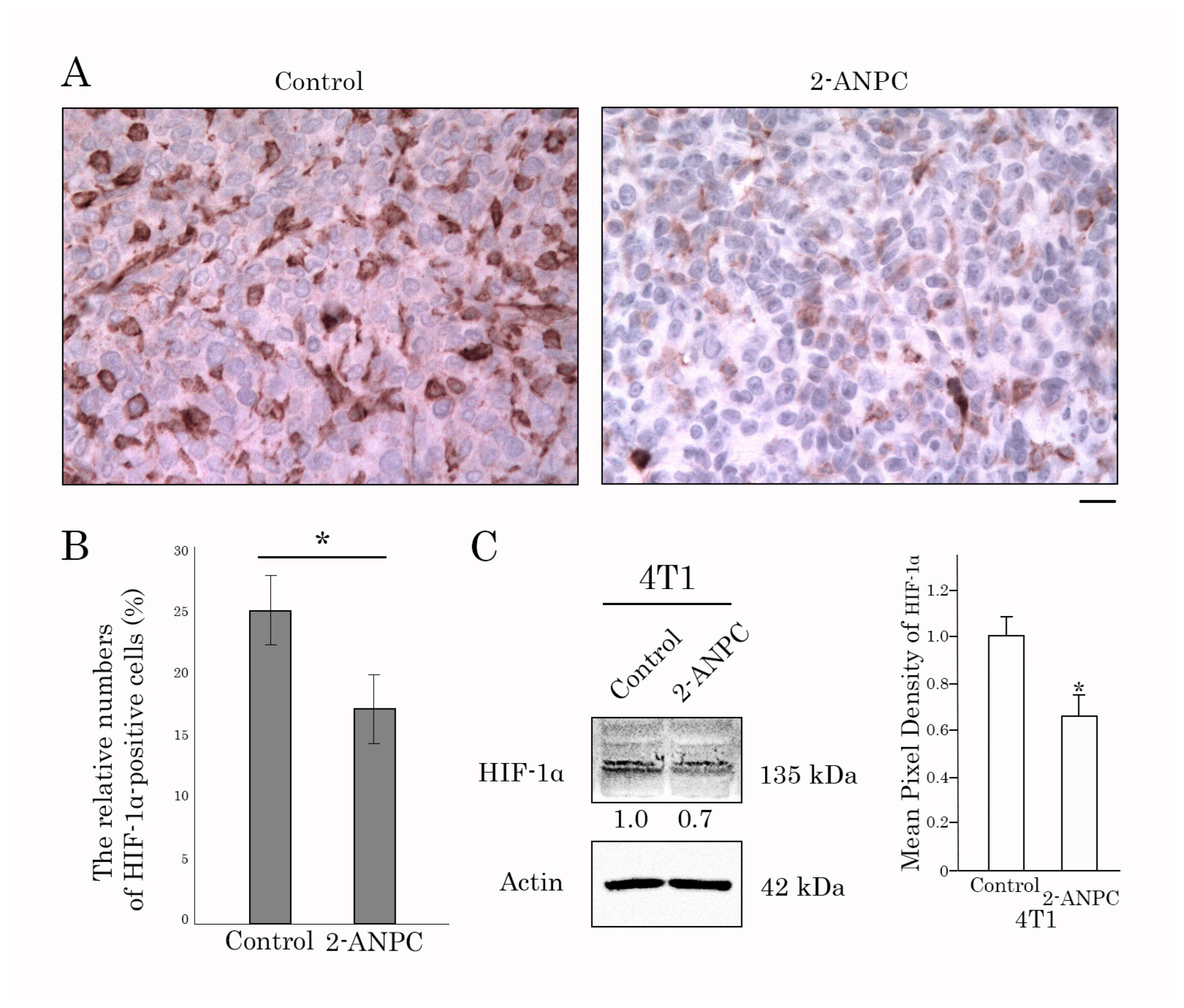

3.3. 2-ANPC Inhibits Tumor Growth and Decreases HIF-1α, VEGFR1, and VEGFR3 Expression In Vivo

3.4. Molecular Modeling Studies

3.4.1. Folding and Binding Site Search

3.4.2. Site Mapping and Multi-Ligand Dynamics

3.5. HIF Active Complex Binding Hypothesis

3.5.1. Folding and Molecular Dynamics

3.5.2. Site Mapping and Docking of HIF-1α and HIF-1β

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-ANPC | 2-Amino-1-benzamido-5-(2-(naphthalene-2-yl)-2-oxoethylidene)-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1-H-pyrrole-3-carboxamide |

| 2-ME2 | 2-Methoxyestradiol |

| ARNT/HIF-1 β | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator/Hypoxia-inducible factor-1β |

| bHLH | Basic helix–loop–helix |

| CBP | CREB-binding protein |

| CRM1 | Chromosome region maintenance 1 |

| CTAD | C-terminal transactivation domain |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HDAC | Class II histone deacetylase |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α |

| HSP90 | Heat shock protein 90 |

| ID | Inhibitory Domain |

| IDRs | Intrinsically Disordered Regions |

| IFD score | Energy spent on formation of the laying of the compound in the binding site and binding energy of ligand and protein |

| IHC | Immunohistochemical |

| MTA | Microtubule-targeting agent |

| NAMD | Nanoscale Molecular Dynamics |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| NTAD | N-terminal transcription activation domain |

| ODD | Oxygen-dependent degradation |

| PARP | Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase |

| PAS | Per-ARNT-Sim domain |

| PDB | Protein data bank |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| pVHL | Von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor protein |

| RT-PCR | Real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TMA | Tissue microarray |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

| VMD | Visual Molecular Dynamics |

| YC-1 | Lificiguat |

References

- Semenza, G.L. HIF-1 and Mechanisms of Hypoxia Sensing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001, 13, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebestyén, A.; Kopper, L.; Dankó, T.; Tímár, J. Hypoxia Signaling in Cancer: From Basics to Clinical Practice. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2021, 27, 1609802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Zadeh, L.R.; Baradaran, B.; Molavi, O.; Ghesmati, Z.; Sabzichi, M.; Ramezani, F. Up-down Regulation of HIF-1α in Cancer Progression. Gene 2021, 798, 145796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xing, C.; Deng, Y.; Ye, C.; Peng, H. HIF-1α Signaling: Essential Roles in Tumorigenesis and Implications in Targeted Therapies. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Xu, D.; Hu, W.; Feng, Z. The Interplay Between Tumor Suppressor p53 and Hypoxia Signaling Pathways in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 648808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, D.; Zhang, T.; Hu, W.; Feng, Z. Gain-of-Function Mutant P53 in Cancer Progression and Therapy. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Fermin, J.M.; Knackstedt, M.; Noonan, M.J.; Powell, T.; Goodreau, L.; Daniel, E.K.; Rong, X.; Moore-Medlin, T.; Khandelwal, A.R.; et al. Everolimus downregulates STAT3/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway to inhibit angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in TP53 mutant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Oncotarget 2023, 14, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, M.; Kasperczyk, H.; Fulda, S.; Debatin, K.M. Role of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Alpha in Modulation of Apoptosis Resistance. Oncogene 2007, 26, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qannita, R.A.; Alalami, A.I.; Harb, A.A.; Aleidi, S.M.; Taneera, J.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; El-Huneidi, W.; Saleh, M.A.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Semreen, M.H.; et al. Targeting Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) in Cancer: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Pathway Regulation. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, Y.; Chow, C.C.T.; Kambe, G.; Suwa, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Takahashi, I.; Harada, H.; Nam, J.M. An overview of the recent development of anticancer agents targeting the hif-1 transcription factor. Cancers 2021, 13, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seredinski, S.; Boos, F.; Günther, S.; Oo, J.A.; Warwick, T.; Izquierdo Ponce, J.; Lillich, F.F.; Proschak, E.; Knapp, S.; Gilsbach, R.; et al. DNA topoisomerase inhibition with the HIF inhibitor acriflavine promotes transcription of lncRNAs in endothelial cells. Mol. Ther. Nucl. Acids 2022, 27, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Gilkes, D.M.; Chaturvedi, P.; Luo, W.; Hu, H.; Takano, N.; Liang, H.; Semenza, G.L. Ganetespib blocks HIF-1 activity and inhibits tumor growth, vascularization, stem cell maintenance, invasion, and metastasis in orthotopic mouse models of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamori, H.; Yamasaki, T.; Kitadai, R.; Minamishima, Y.A.; Nakamura, E. Development of drugs targeting hypoxia-inducible factor against tumor cells with VHL mutation: Story of 127 years. Cancer Sci. 2023, 114, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Jeong, J.W.; Park, J.A.; Lee, J.W.; Seo, J.H.; Jung, B.K.; Bae, M.K.; Kim, K.W. Regulation of the HIF-1alpha stability by histone deacetylases. Oncol. Rep. 2007, 17, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schoepflin, Z.R.; Shapiro, I.M.; Risbud, M.V. Class I and IIa HDACs Mediate HIF-1alpha Stability Through PHD2-Dependent Mechanism, While HDAC6, a Class IIb Member, Promotes HIF-1alpha Transcriptional Activity in Nucleus Pulposus Cells of the Intervertebral Disc. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Feldman, M.J.; Wang, H.; Pang, Y.; Maggio, D.M.; Zhu, D.; Nesvick, C.L.; Dmitriev, P.; Bullova, P.; et al. Vorinostat suppresses hypoxia signaling by modulating nuclear translocation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 56110–56125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Yamaguchi, J.; Shoji, K.; Nangaku, M. Anthracycline inhibits recruitment of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors and suppresses tumor cell migration and cardiac angiogenic response in the host. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 34866–34882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galembikova, A.R.; Dunaev, P.D.; Bikinieva, F.F.; Mustafin, I.G.; Kopnin, P.B.; Zykova, S.S.; Mukhutdinova, F.I.; Sarbazyan, E.A.; Boichuk, S.V. Mechanisms of cytotoxic activity of pyrrole-carboxamides against multidrug-resistant tumor cell sublines. Usp. Mol. Onkol. 2023, 10, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichuk, S.; Galembikova, A.; Syuzov, K.; Dunaev, P.; Bikinieva, F.; Aukhadieva, A.; Zykova, S.; Igidov, N.; Gankova, K.; Novikova, M.; et al. The Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activities of Pyrrole-Based Carboxamides: The Novel Tubulin Inhibitors Targeting the Colchicine-Binding Site. Molecules 2021, 26, 5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizimova, I.A.; Igidov, N.M.; Kiselev, M.A.; Dmitriev, M.V.; Chashchina, S.V.; Siutkina, A.I. Synthesis of New 2-Aminopyrrole Derivatives by Reaction of Furan-2,3-Diones 3-Acylhydrazones with CH-Nucleophiles. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2020, 90, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichuk, S.; Galembikova, A.; Dunaev, P.; Valeeva, E.; Shagimardanova, E.; Gusev, O.; Khaiboullina, S. A Novel Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Switch Promotes Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Drug Resistance. Molecules 2017, 22, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making Protein Folding Accessible to All. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.C.; Hardy, D.J.; Maia, J.D.C.; Stone, J.E.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Bernardi, R.C.; Buch, R.; Fiorin, G.; Hénin, J.; Jiang, W.; et al. Scalable Molecular Dynamics on CPU and GPU Architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; Chipot, C.; Skeel, R.D.; Kalé, L.; Schulten, K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, R.B.; Zhu, X.; Shim, J.; Lopes, P.E.M.; Mittal, J.; Feig, M.; MacKerell, A.D. Optimization of the Additive CHARMM All-Atom Protein Force Field Targeting Improved Sampling of the Backbone ϕ, ψ and Side-Chain χ 1 and χ 2 Dihedral Angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerell, A.D.; Feig, M.; Brooks, C.L. Improved Treatment of the Protein Backbone in Empirical Force Fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerell, A.D.; Bashford, D.; Bellott, M.; Dunbrack, R.L.; Evanseck, J.D.; Field, M.J.; Fischer, S.; Gao, J.; Guo, H.; Ha, S.; et al. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnon, M.; Goullieux, M.; Röhrig, U.F.; Perez, M.A.S.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissParam 2023: A Modern Web-Based Tool for Efficient Small Molecule Parametrization. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 6469–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, A. Software News and Updates Gabedit—A Graphical User Interface for Computational Chemistry Softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 32, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, K.J.; Chow, D.E.; Xu, H.; Dror, R.O.; Eastwood, M.P.; Gregersen, B.A.; Klepeis, J.L.; Kolossvary, I.; Moraes, M.A.; Sacerdoti, F.D.; et al. Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE SC 2006 Conference (SC’06), Tampa, FL, USA, 11–17 November 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Wu, C.; Ghoreishi, D.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Damm, W.; Ross, G.A.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Russell, E.; Von Bargen, C.D.; et al. OPLS4: Improving Force Field Accuracy on Challenging Regimes of Chemical Space. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4291–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Pincus, D.L.; Rapp, C.S.; Day, T.J.F.; Honig, B.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. A Hierarchical Approach to All-Atom Protein Loop Prediction. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 2004, 55, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Xiang, Z.; Honig, B. On the Role of the Crystal Environment in Determining Protein Side-Chain Conformations. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 320, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T. New Method for Fast and Accurate Binding-site Identification and Analysis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2007, 69, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T.A. Identifying and Characterizing Binding Sites and Assessing Druggability. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W.; Day, T.; Jacobson, M.P.; Friesner, R.A.; Farid, R. Novel Procedure for Modeling Ligand/Receptor Induced Fit Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid, R.; Day, T.; Friesner, R.A.; Pearlstein, R.A. New Insights about HERG Blockade Obtained from Protein Modeling, Potential Energy Mapping, and Docking Studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 3160–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, W.; Beard, H.S.; Farid, R. Use of an Induced Fit Receptor Structure in Virtual Screening. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2006, 67, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Puig, N.; Veprintsev, D.B.; Fersht, A.R. Binding of Natively Unfolded HIF-1α ODD Domain to P53. Mol. Cell 2005, 17, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyqvist, I.; Dogan, J. Characterization of the Dynamics and the Conformational Entropy in the Binding between TAZ1 and CTAD-HIF-1α. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, D.; Yue, F.; Qi, Y.; Dou, M.; Cui, L.; Xing, Y. The Potential Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 in the Progression and Therapy of Central Nervous System Diseases. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 20, 1651–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Nam, H.J.; Lee, J.; Park, D.Y.; Kim, C.; Yu, Y.S.; Kim, D.; Park, S.W.; Bhin, J.; Hwang, D.; et al. Methylation-Dependent Regulation of HIF-1α Stability Restricts Retinal and Tumour Angiogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, F.R.; Fatchiyah, F. Methylation Impact Analysis of Erythropoietin (EPO) Gene to Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) Activity. Bioinformation 2013, 9, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appling, F.D.; Berlow, R.B.; Stanfield, R.L.; Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. The Molecular Basis of Allostery in a Facilitated Dissociation Process. Structure 2021, 29, 1327–1338.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, B.; Carbone, A. Soft Disorder Modulates the Assembly Path of Protein Complexes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kastrenopoulou, A.; Larrouture, Q.; Athanasou, N.A.; Knowles, H.J. Angiopoietin-like 4 promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation and migration and stimulates osteo-clastogenesis. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, P.H. The HIF pathway in cancer. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 16, 523–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Chai, H.; Yu, Z.; Ge, W.; Kang, N.; Xia, W.; Che, Y. HIF-1α effects on angiogenic potential in human small cell lung carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 30, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, A.G.; Morya, V.K.; Kwak, M.K.; Oh, J.U.; Noh, K.C. A Molecular Perspective on HIF-1α and Angiogenic Stimulator Networks and Their Role in Solid Tumors: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voron, T.; Marcheteau, E.; Pernot, S.; Colussi, O.; Tartour, E.; Taieb, J.; Terme, M. Control of the immune response by pro-angiogenic factors. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Du, W.; Gong, L.; Chang, H.; Zou, Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: An accomplice in solid tumor progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Roy, S.; Singh, M.; Kaithwas, G. Regulation of Transactivation at C-TAD Domain of HIF-1α by Factor-Inhibiting HIF-1α (FIH-1): A Potential Target for Therapeutic Interven-tion in Cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2407223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagao, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Koyasu, S.; Chow, C.C.T.; Harada, H. HIF-1-Dependent Repro-gramming of Glucose Metabolic Pathway of Cancer Cells and Its Therapeutic Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Keibler, M.A.; Stephanopoulos, G. Review of metabolic pathways activated in cancer cells as determined through isotopic labeling and network analysis. Metab. Eng. 2017, 43, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoud, G.N.; Li, W. HIF-1α pathway: Role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Kumaravel, S.; Sharma, A.; Duran, C.L.; Bayless, K.J.; Chakraborty, S. Hypoxic tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer therapy. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, J.L.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X.P.; Pribluda, V.S.; Swartz, G.M.; Van Waes, C. 2-Methoxyestradiol Inhibits Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α, Tumor Growth, and Angiogenesis and Augments Paclitaxel Efficacy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 8665–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y.M.; Mokhlis, H.A.; Ismail, A.; Doghish, A.S.; Sobhy, M.H.; Hassanein, S.S.; El-Dakroury, W.A.; Mariee, A.D.; Salama, S.A.; Sharaky, M. 2-Methoxyestradiol Sensitizes Tamoxifen-Resistant MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells via Downregulating HIF-1α. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Zhang, J.; Lei, X.; Xie, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, Z.; Tang, G. Advances in Antitumor Research of HIF-1α Inhibitor YC-1 and Its Derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 133, 106400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.H.; Hung, H.Y. Synthetic Strategy and Structure–Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies of 3-(5′-Hydroxymethyl-2′-Furyl)-1-Benzyl Indazole (YC-1, Lificiguat): A Review. RSC Adv. 2021, 12, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangraviti, A.; Raghavan, T.; Volpin, F.; Skuli, N.; Gullotti, D.; Zhou, J.; Asnaghi, L.; Sankey, E.; Liu, A.; Wang, Y.; et al. HIF-1α- Targeting Acriflavine Provides Long Term Survival and Radiological Tumor Response in Brain Cancer Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabjeesh, N.J.; Escuin, D.; LaVallee, T.M.; Pribluda, V.S.; Swartz, G.M.; Johnson, M.S.; Willard, M.T.; Zhong, H.; Simons, J.W.; Giannakakou, P. 2ME2 Inhibits Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis by Disrupting Microtubules and Dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, R.J.; Lin, C.M.; Flynn, E.; Folkman, J.; Hamel, E. 2-Methoxyestradiol, an Endogenous Mammalian Metabolite, Inhibits Tubulin Polymerization by Interacting at the Colchicine Site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 3964–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poch, A.; Villanelo, F.; Henriquez, S.; Kohen, P.; Muñoz, A.; Strauss, J.F.; Devoto, L. Molecular Modelling Predicts That 2-Methoxyestradiol Disrupts HIF Function by Binding to the PAS-B Domain. Steroids 2019, 144, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.; Love, R.; Nilsson, C.L.; Bergqvist, S.; Nowlin, D.; Yan, J.; Liu, K.K.C.; Zhu, J.; Chen, P.; Deng, Y.L.; et al. Identification of Cys255 in HIF-1α as a Novel Site for Development of Covalent Inhibitors of HIF-1α/ARNT PasB Domain Protein-Protein Interaction. Protein Sci. 2012, 21, 1885–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Potluri, N.; Lu, J.; Kim, Y.; Rastinejad, F. Structural Integration in Hypoxia-Inducible Factors. Nature 2015, 524, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, M.; O’Brate, A.; Giannakakou, P. Microtubule disruption targets HIF-1alpha mRNA to cytoplasmic P-bodies for translational repression. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 192, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVallee, T.M.; Burke, P.A.; Swartz, G.M.; Hamel, E.; Agoston, G.E.; Shah, J.; Suwandi, L.; Hanson, A.D.; Fogler, W.E.; Sidor, C.F.; et al. Significant antitumor activity in vivo following treatment with the microtubule agent ENMD-1198. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zykova, S.S.; Gessel, T.; Galembikova, A.; Mozhaitsev, E.S.; Borisevich, S.S.; Igidov, N.; Egorova, E.S.; Mikheeva, E.; Khromova, N.; Kopnin, P.; et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α, a Novel Molecular Target for a 2-Aminopyrrole Derivative: Biological and Molecular Modeling Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010115

Zykova SS, Gessel T, Galembikova A, Mozhaitsev ES, Borisevich SS, Igidov N, Egorova ES, Mikheeva E, Khromova N, Kopnin P, et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α, a Novel Molecular Target for a 2-Aminopyrrole Derivative: Biological and Molecular Modeling Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleZykova, Svetlana S., Tatyana Gessel, Aigul Galembikova, Evgenii S. Mozhaitsev, Sophia S. Borisevich, Nazim Igidov, Emiliya S. Egorova, Ekaterina Mikheeva, Natalia Khromova, Pavel Kopnin, and et al. 2026. "Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α, a Novel Molecular Target for a 2-Aminopyrrole Derivative: Biological and Molecular Modeling Study" Cancers 18, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010115

APA StyleZykova, S. S., Gessel, T., Galembikova, A., Mozhaitsev, E. S., Borisevich, S. S., Igidov, N., Egorova, E. S., Mikheeva, E., Khromova, N., Kopnin, P., Galyautdinova, A., Luzhanin, V., Shustov, M., & Boichuk, S. (2026). Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α, a Novel Molecular Target for a 2-Aminopyrrole Derivative: Biological and Molecular Modeling Study. Cancers, 18(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010115