Factors Affecting Psychosocial Distress in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: BRIGHTLIGHT Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Cohort Study Results

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.3. Procedures and Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Clinical, and Psychosocial Characteristics

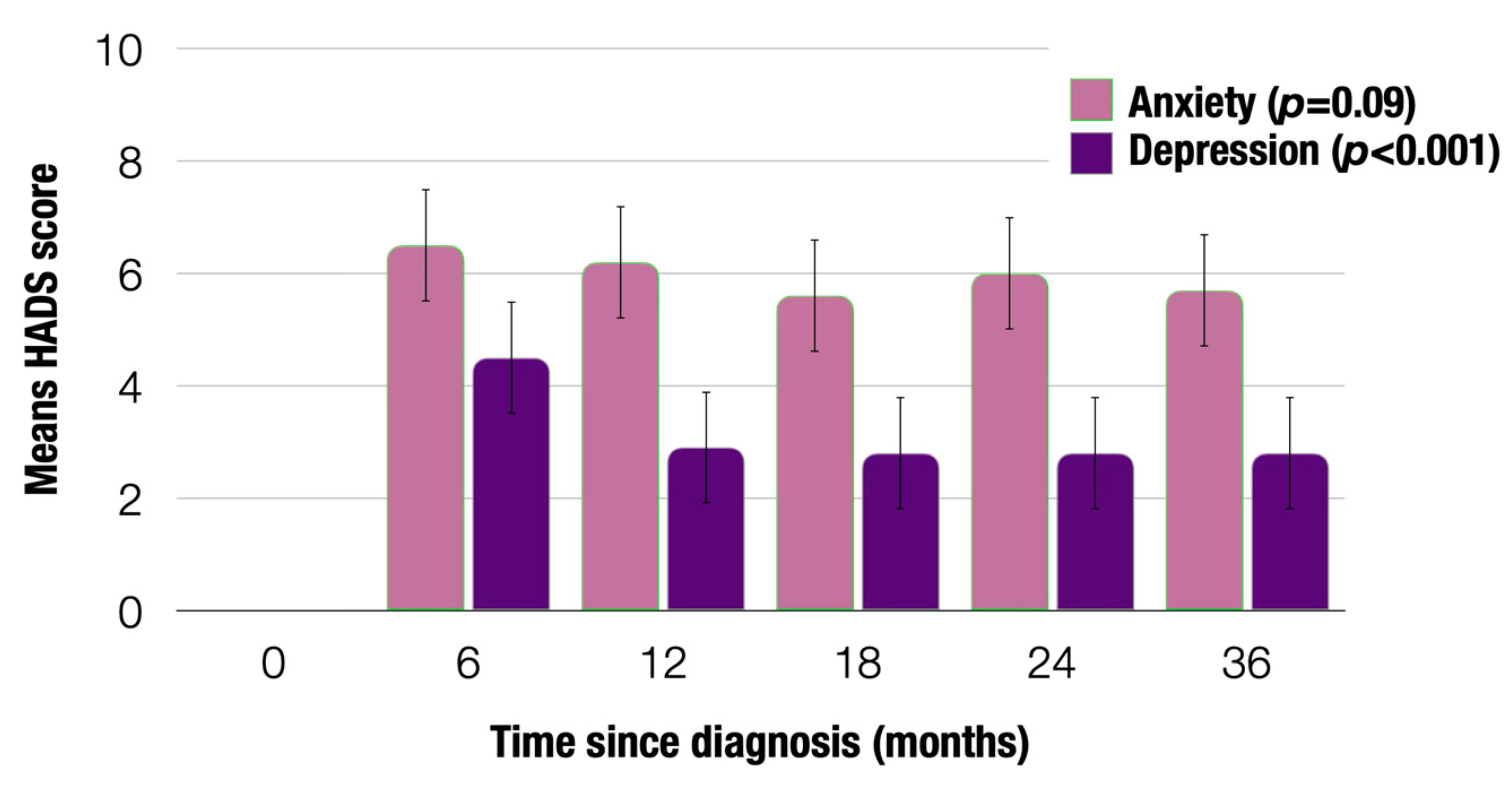

3.2. Quantitative Findings

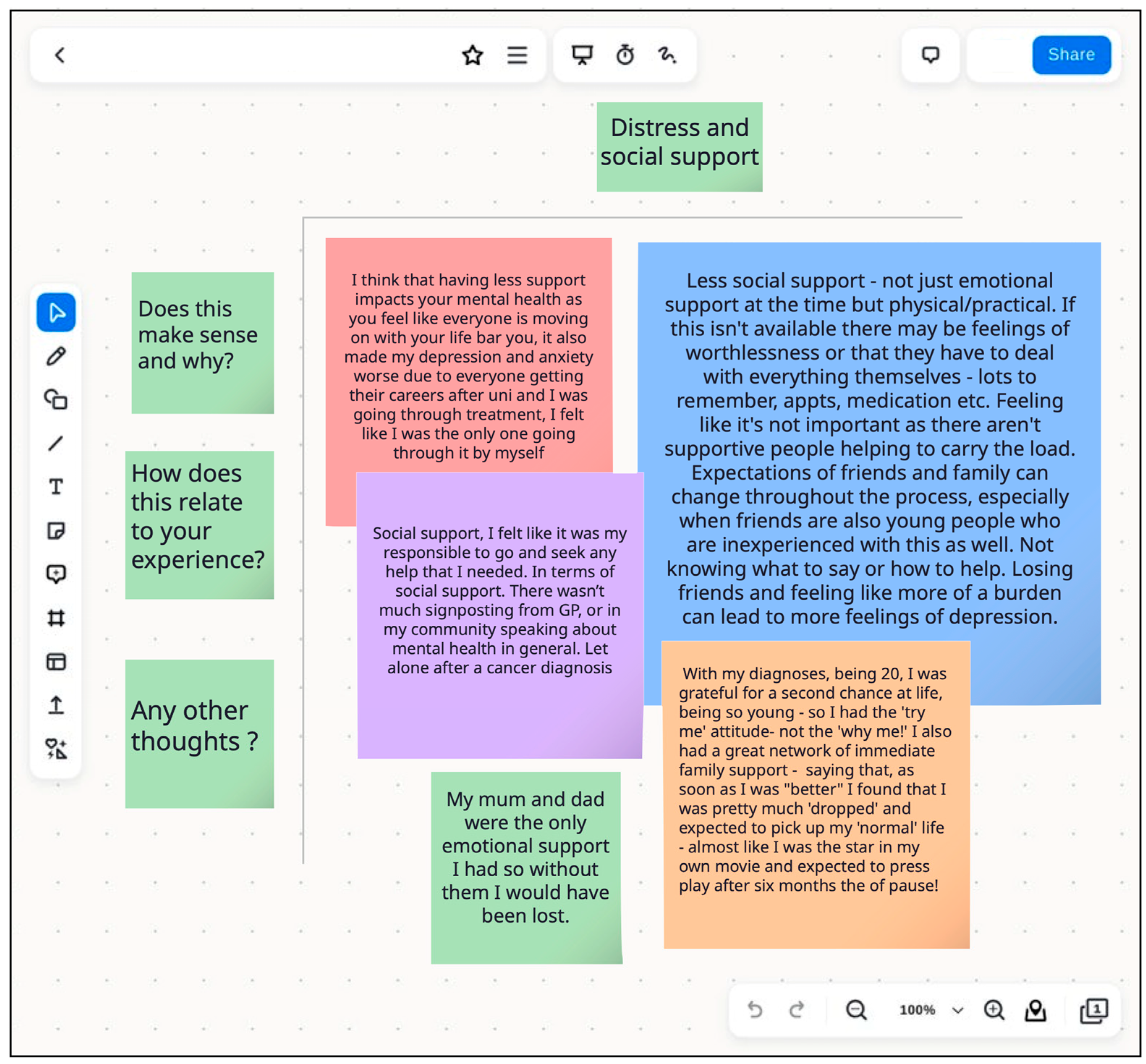

3.3. Findings from the YAP Workshops

“I’m actually really upset about this, [but] I had to be strong for everybody else. And I think that’s something that kind of gets missed a lot because you have a family member there. So my mom sat there crying, but she would cry the whole way home, and I had to make sure she was okay. So without, you know, going into too much negativity, I had to sort of be the strong one. And I think that definitely weighed on my mental health”.

“…as soon as I was better I found that I was pretty much dropped and expected to pick up my normal, almost like I was the star in my own movie and expected to press play after 6 months of pause.”

“…I think it’s more socially acceptable to have to need to seek help for mental health and are, like, if I was having a bad day, I’d be a lot more vocal about it than my partner would be. And so I think it’s probably, personally, I think men try not to talk about things like that…”

“…it wasn’t till a few years later that I actually realized the severity [of the diagnosis].”

“I was very naïve and unaware of the severity of my cancer. I think this worked in my favour with my mental health.”

“I think there will be a lot of young people who just haven’t received a diagnosis yet. So then down the line, it may appear that if they are struggling mentally, it’s been, like, directly because of their cancer and what they’ve been through… But it could be that they may be already suffering with anxiety. But it was just kind of put down to being a teenager and, like, normal worries.”

“If you’re a person who tends to worry a lot, when the thing you’re worrying about actually happens, you suddenly become very calm. Because that disaster I’ve been waiting for is here.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, C.; Irvine, L.; Welham, C. Children, Teenagers and Young Adults UK Cancer Statistics Report 2021. Available online: https://www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/nicr/FileStore/PDF/UKReports/Filetoupload,1024819,en.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- NHS England. NHS England Service Specifications for Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Networks—Principal Treatment Centres. Available online: https://www.engage.england.nhs.uk/consultation/teenager-and-young-adults-cancer-services/user_uploads/service-specification-tya-principal-treatment-centres-and-networks.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Cancer Research UK. Young People’s Cancers Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/young-peoples-cancers#heading-Zero (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Close, A.G.; Dreyzin, A.; Miller, K.D.; Seynnaeve, B.K.N.; Rapkin, L.B. Adolescent and young adult oncology-past, present, and future. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, R.D.; Ferrari, A.; Ries, L.; Whelan, J.; Bleyer, W.A. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Martin, J.; Orme, L.; Seddon, B.; Desai, J.; Nicholls, W.; Thomson, D.; Porter, D.; McCowage, G.; Underhill, C.; et al. Gender differences in doxorubicin pharmacology for subjects with chemosensitive cancers of young adulthood. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Stark, D.; Peccatori, F.A.; Fern, L.; Laurence, V.; Gaspar, N.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Smith, O.; De Munter, J.; Derwich, K.; et al. Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer: A position paper from the AYA Working Group of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE). ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, O.; Reeve, B.B.; Darlington, A.S.; Cheung, C.K.; Sodergren, S.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Salsman, J.M. Next Step for Global Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology: A Core Patient-Centered Outcome Set. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, A.; Bernasconi, A.; McCabe, M.G.; Guevara, M.; Gatta, G.; Botta, L.; the RARECAREnet Working Group; Ries, L.; Bleyer, A. Is the cancer survival improvement in European and American adolescent and young adults still lagging behind that in children? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Clark, S.E.; Gerrand, C.; Gilchrist, K.; Lawal, M.; Maio, L.; Martins, A.; Storey, L.; Taylor, R.M.; Wells, M.; et al. Patients’ Experiences of a Sarcoma Diagnosis: A Process Mapping Exercise of Diagnostic Pathways. Cancers 2023, 15, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A.; Lyratzopoulos, G.; Whelan, J.; Taylor, R.M.; Barber, J.; Gibson, F.; Fern, L.A. Diagnostic timeliness in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A cross-sectional analysis of the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rojas, T.; Neven, A.; Terada, M.; García-Abós, M.; Moreno, L.; Gaspar, N.; Péron, J. Access to Clinical Trials for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: A Meta-Research Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 3, pkz057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fern, L.A.; Lewandowski, J.A.; Coxon, K.M.; Whelan, J.; for the National Cancer Research Institute Teenage and Young Adult Clinical Studies Group, UK. Available, accessible, aware, appropriate, and acceptable: A strategy to improve participation of teenagers and young adults in cancer trials. Lancet Oncology 2014, 15, e341–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, E.; Stratton, K.L.; Leisenring, W.M.; Nathan, P.C.; Ford, J.S.; Freyer, D.R.; McNeer, J.L.; Stock, W.; Stovall, M.; Krull, K.R.; et al. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: A retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.K.; Hardy, K.K.; Zhang, N.; Edelstein, K.; Srivastava, D.; Zeltzer, L.; Stovall, M.; Seibel, N.L.; Leisenring, W.; Armstrong, G.T.; et al. Psychosocial and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Adolescent and Early Young Adult Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; McDonald, F.E.; Zebrack, B.; Medlow, S. Emerging issues among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 31, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.F.; Chen, M.X.; Yin, G.; Lin, R.; Zhong, Y.J.; Dong, Q.Q.; Wong, H.M. The global, regional, and national burden of cancer among adolescents and young adults in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A population-based study. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Kurup, S.; Devaraja, K.; Shanawaz, S.; Reynolds, L.; Ross, J.; Bezjak, A.; Gupta, A.A.; Kassam, A. Adapting an Adolescent and Young Adult Program Housed in a Quaternary Cancer Centre to a Regional Cancer Centre: Creating Equitable Access to Developmentally Tailored Support. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrady, M.E.; Willard, V.W.; Williams, A.M.; Brinkman, T.M. Psychological Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 42, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunguc, C.; Winter, D.L.; Heymer, E.J.; Rudge, G.; Polanco, A.; Birchenall, K.A.; Griffin, M.; Anderson, R.A.; Wallace, W.H.B.; Hawkins, M.M.; et al. Risks of adverse obstetric outcomes among female survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer in England (TYACSS): A population-based, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barendse, M.E.A.; Flannery, J.; Cavanagh, C.; Aristizabal, M.; Becker, S.P.; Berger, E.; Breaux, R.; Campione-Barr, N.; Church, J.A.; Crone, E.A.; et al. Longitudinal Change in Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Res. Adolesc. 2023, 33, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Jacobsen, R.L.; McDonald, F.E.J.; Pflugeisen, C.M.; Bibby, K.; Macpherson, C.F.; Thompson, K.; Murnane, A.; Anazodo, A.; Sansom-Daly, U.M.; et al. Beyond Medical Care: How Different National Models of Care Impact the Experience of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebrack, B.J. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 2289–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.A.; King, J.B.; Lupo, P.J.; Durbin, E.B.; Tai, E.; Mills, K.; Van Dyne, E.; Buchanan Lunsford, N.; Henley, S.J.; Wilson, R.J. Counts, incidence rates, and trends of pediatric cancer in the United States, 2003–2019. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 1337–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J.; Zotow, E.; Smith, L.; Johnson, S.A.; Thomson, C.S.; Ahmad, A.; Murdock, L.; Nagarwalla, D.; Forman, D. 25 year trends in cancer incidence and mortality among adults aged 35–69 years in the UK, 1993–2018: Retrospective secondary analysis. BMJ 2024, 384, e076962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.C. The ‘Lost Tribe’ and the need for a promised land: The challenge of cancer in teenagers and young adults. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 280–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Thomas, D.; Franklin, A.R.; Hayes-Lattin, B.M.; Mascarin, M.; van der Graaf, W.; Albritton, K.H. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: Some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4850–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelagnoli, M.P.; Pritchard, J.; Phillips, M.B. Adolescent oncology--a homeland for the “lost tribe”. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 2571–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, V.; Horner, L.; Klug, S.J.; Tanaka, L.F. Prevalence and risk of psychological distress, anxiety and depression in adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 18354–18367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.P.; Ruble, K.; Kozachik, S. Psychosocial interventions for adolescents and young adults with cancer: An integrative review. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 37, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košir, U. Methodological Issues in Psychosocial Research in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Populations. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Cooper, A.B.; Joiner, T.E.; Duffy, M.E.; Binau, S.G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.; McDonnell, G.; DeRosa, A.; Schuler, T.; Philip, E.; Peterson, L.; Touza, K.; Jhanwar, S.; Atkinson, T.M.; Ford, J.S. Psychosocial outcomes and interventions among cancer survivors diagnosed during adolescence and young adulthood (AYA): A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, S.; Engstrom, T.; Lee, W.R.; Forbes, C.; Walker, R.; Bradford, N.; Pole, J.D. Mental health patient-reported outcomes among adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 18381–18393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neylon, K.; Condren, C.; Guerin, S.; Looney, K. What Are the Psychosocial Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer? A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosgen, B.K.; Moss, S.J.; Fiest, K.M.; McKillop, S.; Diaz, R.L.; Barr, R.D.; Patten, S.B.; Deleemans, J.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Psychiatric Disorder Incidence Among Adolescents and Young Adults Aged 15-39 With Cancer: Population-Based Cohort. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022, 6, pkac077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, H.; Garg, S.; Zhang, B. Fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosir, U.; Wiedemann, M.; Wild, J.; Bowes, L. Psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors: A systematic review of prevalence and predictors. Cancer Rep. 2019, 2, e1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, S.; Garland, A.; Yan, A.P.; Lambert, P.; Xue, L.; Decker, K.; Israels, S.J.; Banerji, S.; Bolton, J.M.; Deleemans, J.M.; et al. Mental Disorders Among Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: A Canadian Population–Based and Sibling Cohort Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1509–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrke, A.; Leung, B.; Srikanthan, A.; McDonald, M.; Bates, A.; Ho, C. Distinct Features of Psychosocial Distress of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer Compared to Adults at Diagnosis: Patient-Reported Domains of Concern. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, N.K.; McDonald, F.E.J.; Bibby, H.; Kok, C.; Patterson, P. Psychological, functional and social outcomes in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors over time: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, E.; El-Khouri, B.; Ljungman, G.; von Essen, L. Empirically derived psychosocial states among adolescents diagnosed with cancer during the acute and extended phase of survival. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1722–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avutu, V.; Lynch, K.A.; Barnett, M.E.; Vera, J.A.; Glade Bender, J.L.; Tap, W.D.; Atkinson, T.M. Psychosocial Needs and Preferences for Care among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients (Ages 15–39): A Qualitative Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, G.; François, C.; Harju, E.; Dehler, S.; Roser, K. The long-term impact of cancer: Evaluating psychological distress in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors in Switzerland. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geue, K.; Brähler, E.; Faller, H.; Härter, M.; Schulz, H.; Weis, J.; Koch, U.; Wittchen, H.U.; Mehnert, A. Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial distress in German adolescent and young adult cancer patients (AYA). Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.C.; McNeil, R.; Drew, S.; Dunt, D.; Kosola, S.; Orme, L.; Sawyer, S.M. Psychological Distress and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer and Their Parents. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2016, 5, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geue, K.; Göbel, P.; Leuteritz, K.; Nowe, E.; Sender, A.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Friedrich, M. Anxiety and depression in young adult German cancer patients: Time course and associated factors. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/social-support# (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Warner, E.L.; Kent, E.E.; Trevino, K.M.; Parsons, H.M.; Zebrack, B.J.; Kirchhoff, A.C. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 2016, 122, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neinstein, L.S.; Katzman, D.K.; Callahan, T.; Joffe, A. Neinstein’s Adolescent and Young Adult Health Care: A Practical Guide, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Husson, O.; Zebrack, B.J.; Aguilar, C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: Who remains at risk of poor social functioning over time? Cancer 2017, 123, 2743–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Hou, X. Incidence of suicide among adolescent and young adult cancer patients: A population-based study. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heynemann, S.; Thompson, K.; Moncur, D.; Silva, S.; Jayawardana, M.; Lewin, J. Risk factors associated with suicide in adolescents and young adults (AYA) with cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 7339–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.S.; Reinius, M.A.; Hatcher, H.M.; Ajithkumar, T.V. Anticancer chemotherapy in teenagers and young adults: Managing long term side effects. BMJ 2016, 354, i4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Sack, A.M.; Menna, R.; Setchell, S.R.; Maan, C.; Cataudella, D. Posttraumatic growth, coping strategies, and psychological distress in adolescent survivors of cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 29, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ander, M.; Grönqvist, H.; Cernvall, M.; Engvall, G.; Hedström, M.; Ljungman, G.; Lyhagen, J.; Mattsson, E.; von Essen, L. Development of health-related quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression among persons diagnosed with cancer during adolescence: A 10-year follow-up study. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenten, C.; Martins, A.; Fern, L.A.; Gibson, F.; Lea, S.; Ngwenya, N.; Whelan, J.S.; Taylor, R.M. Qualitative study to understand the barriers to recruiting young people with cancer to BRIGHTLIGHT: A national cohort study in England. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; McCabe, M.G.; Gibson, F.; Raine, R.; et al. Description of the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort: The evaluation of teenage and young adult cancer services in England. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Solanki, A.; Hooker, L.; Carluccio, A.; Pye, J.; Jeans, D.; Frere-Smith, T.; Gibson, F.; Barber, J.; et al. Development and validation of the BRIGHTLIGHT Survey, a patient-reported experience measure for young people with cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Whelan, J.S.; Gibson, F.; Morgan, S.; Fern, L.A. Involving young people in BRIGHTLIGHT from study inception to secondary data analysis: Insights from 10 years of user involvement. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2018, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fern, L.A.; Taylor, R.M.; Barber, J.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.; Lea, S.; Martins, A.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; Gibson, F.; et al. Processes of care and survival associated with treatment in specialist teenage and young adult cancer centres: Results from the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, O.; Zebrack, B.J.; Block, R.; Embry, L.; Aguilar, C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Cole, S. Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients With Cancer: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.F. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, B.; Kaal, S.E.J.; Custers, J.A.E.; Manten-Horst, E.; Jansen, R.; Servaes, P.; van der Graaf, W.T.A.; Prins, J.B.; Husson, O. Prevalence and correlates of high fear of cancer recurrence in late adolescents and young adults consulting a specialist adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer service. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodermaier, A.; Millman, R.D. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, C.; Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Gómez-Sánchez, D.; Fernández-Montes, A.; Palacín-Lois, M.; Antoñanzas-Basa, M.; Rogado, J.; Manzano-Fernández, A.; Ferreira, E.; et al. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) in cancer patients: Psychometric properties and measurement invariance. Psicothema 2021, 33, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nearchou, F.; Davies, A.; Hennessy, E. Psychometric evaluation of the Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in young adults with chronic health conditions. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2022, 39, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, O.R.; Harries, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Knight, H.; Sherar, L.B.; Varela-Mato, V.; Morling, J.R. What are the strengths and limitations to utilising creative methods in public and patient involvement in health and social care research? A qualitative systematic review. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2024, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Payment Guidance for Researchers and Professionals. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/payment-guidance-for-researchers-and-professionals/27392 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Birch, J.M.; Pang, D.; Alston, R.D.; Rowan, S.; Geraci, M.; Moran, A.; Eden, T.O. Survival from cancer in teenagers and young adults in England, 1979–2003. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennant, S.; Lee, S.C.; Holm, S.; Triplett, K.N.; Howe-Martin, L.; Campbell, R.; Germann, J. The Role of Social Support in Adolescent/Young Adults Coping with Cancer Treatment. Children 2019, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrack, B.; Chesler, M.A.; Kaplan, S. To foster healing among adolescents and young adults with cancer: What helps? What hurts? Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haluska, H.B.; Jessee, P.O.; Nagy, M.C. Sources of social support: Adolescents with cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2002, 29, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanes, L.; Gibson, F. Protecting an adult identity: A grounded theory of supportive care for young adults recently diagnosed with cancer. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 81, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Bona, K.; Baker, K.S.; McCauley, E.; Rosenberg, A.R. Distress and resilience among adolescents and young adults with cancer and their mothers: An exploratory analysis. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2020, 38, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiner, K.; Grossoehme, D.H.; Friebert, S.; Baker, J.N.; Needle, J.; Lyon, M.E. “Living life as if I never had cancer”: A study of the meaning of living well in adolescents and young adults who have experienced cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miedema, B.; Hamilton, R.; Easley, J. From “invincibility” to “normalcy”: Coping strategies of young adults during the cancer journey. Palliat. Support. Care 2007, 5, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baclig, N.V.; Comulada, W.S.; Ganz, P.A. Mental health and care utilization in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7, pkad098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.; Parsa, A.G.; Walsh, C.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Weiner, B.J.; Curtis, J.R.; McCauley, E.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Barton, K. Facilitators and barriers to utilization of psychosocial care in adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: Integrating mobile health perspectives. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.; Schweitzer, J.B.; Hernandez, S.; Molina, S.C.; Keegan, T.H.M. Strategies for recruitment and retention of adolescent and young adult cancer patients in research studies. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 7, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, S.T.; Stevenson, R.; Winpenny, E.M.; Corder, K.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Recruitment and retention into longitudinal health research from an adolescent perspective: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2023, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.; Fern, L.A.; Whelan, J.S.; Taylor, R.M.; BRIGHTLIGHT Study Group. Young people’s opinions of cancer care in England: The BRIGHTLIGHT cohort. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaal, S.E.J.; Husson, O.; van Duivenboden, S.; Jansen, R.; Manten-Horst, E.; Servaes, P.; Prins, J.B.; van den Berg, S.W.; van der Graaf, W.T.A. Empowerment in adolescents and young adults with cancer: Relationship with health-related quality of life. Cancer 2017, 123, 4039–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, O.; Prins, J.B.; Kaal, S.E.; Oerlemans, S.; Stevens, W.B.; Zebrack, B.; van der Graaf, W.T.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) lymphoma survivors report lower health-related quality of life compared to a normative population: Results from the PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Aslam, N.; Lea, S.; Whelan, J.S.; Fern, L.A. Optimizing a retention strategy with young people for BRIGHTLIGHT, a longitudinal cohort study examining the value of specialist cancer care for young people. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2017, 6, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gordon, B.G. Vulnerability in Research: Basic Ethical Concepts and General Approach to Review. Ochsner J. 2020, 20, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonevski, B.; Randell, M.; Paul, C.; Chapman, K.; Twyman, L.; Bryant, J.; Brozek, I.; Hughes, C. Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldiss, S.; Fern, L.A.; Phillips, R.S.; Callaghan, A.; Dyker, K.; Gravestock, H.; Groszmann, M.; Hamrang, L.; Hough, R.; McGeachy, D.; et al. Research priorities for young people with cancer: A UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Frequency | % a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 20.1 (3.3) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 457 | 55.1 | |

| Female | 373 | 44.9 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 730 | 88.0 | |

| Mixed | 14 | 1.7 | |

| Asian | 61 | 7.3 | |

| Black | 15 | 1.8 | |

| Chinese | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Other | 6 | 0.7 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/civil partnership | 26 | 3.1 | |

| Cohabiting | 93 | 11.2 | |

| Single/divorced | 606 | 73.0 | |

| Missing data | 105 | 12.7 | |

| Geographic location | |||

| North East England | 44 | 5.3 | |

| NW | 106 | 12.8 | |

| Yorkshire | 100 | 12.0 | |

| East Midlands | 107 | 12.9 | |

| West Midlands | 120 | 14.5 | |

| London | 165 | 19.9 | |

| South East England | 98 | 11.8 | |

| Sound West England | 90 | 10.8 | |

| Socioeconomic status (IMD quintile) | |||

| 1—most deprived | 184 | 22.2 | |

| 2 | 136 | 16.4 | |

| 3 | 156 | 18.8 | |

| 4 | 182 | 21.9 | |

| 5—least deprived | 152 | 18.3 | |

| Missing data | 20 | 2.4 | |

| Employment status | |||

| Working full/part time | 257 | 31.0 | |

| Education | 274 | 33.0 | |

| Other work (apprentice, intern, volunteer) | 17 | 2.0 | |

| Unemployed | 31 | 3.7 | |

| Long term sick leave | 126 | 15.2 | |

| Not seeking work | 125 | 15.1 | |

| Characteristic | Frequency | % a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type—Birch classification [75] | |||

| Leukemia | 106 | 12.8 | |

| Lymphoma | 267 | 32.2 | |

| Central nervous system | 33 | 4.0 | |

| Bone | 70 | 8.4 | |

| Sarcoma | 59 | 7.1 | |

| Germ cell | 154 | 18.6 | |

| Skin | 31 | 3.7 | |

| Carcinoma (not skin) | 100 | 12.0 | |

| Other b | 10 | 1.2 | |

| Time to diagnosis (days) c | |||

| Mean (SD) | 125.3 (172.6) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 62.0 (29.0, 153.0) | ||

| Disease severity at diagnosis | |||

| Least severe | 461 | 55.5 | |

| Intermediate | 194 | 23.4 | |

| Most severe | 175 | 21.1 | |

| Prognostic score | |||

| <50% | 127 | 15.3 | |

| 50–80% | 239 | 28.8 | |

| >80% | 460 | 55.4 | |

| Missing data | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Treatment type d | |||

| SACT only | 271 | 32.6 | |

| RT only | 14 | 1.7 | |

| Surgery only | 117 | 14.1 | |

| SACT and RT | 106 | 12.8 | |

| SACT and Surgery | 181 | 21.8 | |

| SACT, RT, and Surgery | 77 | 9.3 | |

| RT and Surgery | 36 | 4.3 | |

| Transplant | 19 | 2.3 | |

| Other e | 9 | 1.1 | |

| Characteristic | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HADS a | |||

| Anxiety score, mean (SD) | 6.89 (4.39) | ||

| Borderline, n (%) | 160 (19) | ||

| Moderate/severe, n (%) | 172 (21) | ||

| Depression score, mean (SD) | 4.62 (3.68) | ||

| Borderline, n (%) | 120 (15) | ||

| Moderate/severe, n (%) | 55 (7) | ||

| MSPSS, median (IQR) | |||

| Support—friends | 1.75 (1–2.75) | ||

| Support—family | 1.25 (1–2) | ||

| Support—significant others | 1 (1–2) | ||

| Total support | 1.5 (1.1–2.2) | ||

| Distress Symptom | Test Statistic | p-Value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | |||||

| Age | β = 1.022 | 0.002 | 0.008 to 0.035 | ||

| Gender | β = 0.696 | <0.001 | −0.420 to −0.305 | ||

| Social support | |||||

| From family | β = 1.028 | <0.001 | 1.696 to 1.799 | ||

| From friends | β = 1.030 | <0.001 | 1.631 to 1.732 | ||

| From significant others | β = 1.009 | 0.003 | 1.818 to 1.915 | ||

| Total | β = 1.148 | <0.001 | 0.108 to 0.168 | ||

| Disease severity | |||||

| Between groups | F(2827) = 3.351 | 0.036 | 0.000 to 0.023 | ||

| Low vs. Medium | 1.000 | −0.774 to 1.024 | |||

| Low vs. High | 0.032 | 0.0610 to 1.927 | |||

| Medium vs. High | 0.172 | −0.226 to 1.964 | |||

| Pre-existing mental health condition | U = 385.500 | 0.162 | −1.241 to 0.276 | ||

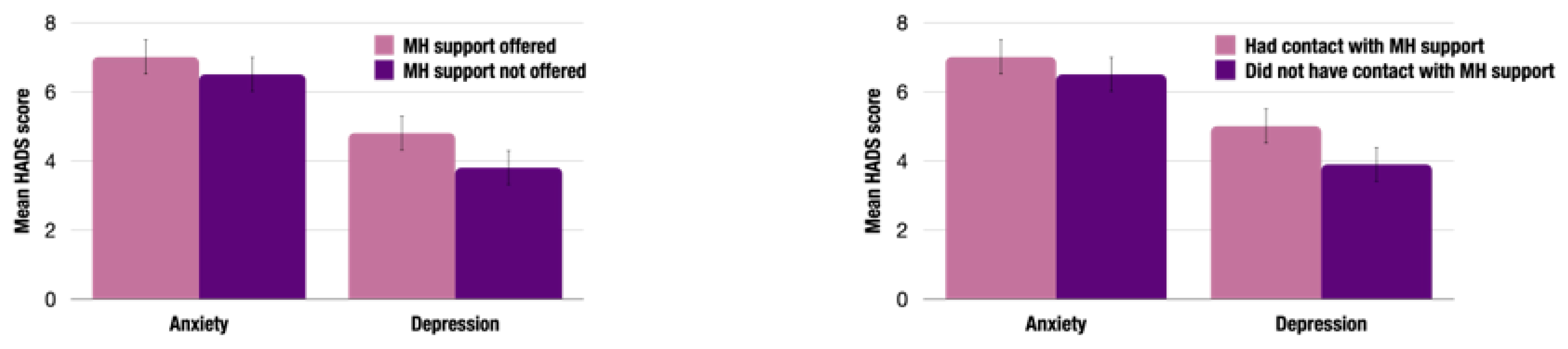

| Offered contact with a mental health professional | t(827) = −1.617 | 0.106 | −0.287 to 0.028 | ||

| Had contact with a mental health professional | t(774) = −1.656 | 0.098 | −0.280 to 0.024 | ||

| Depression | |||||

| Age | β = 1.001 | 0.186 | −0.005 to 0.027 | ||

| Gender | β = 0.729 | <0.001 | −0.388 to −0.246 | ||

| Social support | |||||

| From family | β = 1.033 | <0.001 | 1.254 to 1.378 | ||

| From friends | β = 1.041 | <0.001 | 1.119 to 1.242 | ||

| From significant others | β = 1.015 | <0.001 | 1.367 to 1.485 | ||

| Total | β = 1.192 | <0.001 | 0.140 to 0.212 | ||

| Disease severity | |||||

| Between groups | F(2827) = 3.999 | 0.019 | 0.000 to 0.025 | ||

| Low vs. Medium | 0.020 | −1.610 to −0.100 | |||

| Low vs. High | 0.390 | −1.270 to 0.290 | |||

| Medium vs. High | 1.000 | −0.560 to 1.280 | |||

| Pre-existing mental health condition | U = 431.000 | 0.301 | −1.167 to 0.349 | ||

| Offered contact with a mental health professional | t(827) = −3.672 | <0.001 | −0.452 to −0.136 | ||

| Had contact with a mental health professional | t(774) = 3.840 | <0.001 | −0.450 to −0.145 | ||

| Source of Support | Positive Impacts | Negative Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Family |

|

|

| Friends |

|

|

| Time | Anxiety (Things I Was Worrying About) | Depression (Things I Was Sad About) |

| 6 months |

|

|

| 12 months |

|

|

| 18 months |

|

|

| 2 years |

|

|

| 3 years |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Korenblum, C.; Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Hough, R.; Wickramasinghe, B. Factors Affecting Psychosocial Distress in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: BRIGHTLIGHT Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Cohort Study Results. Cancers 2025, 17, 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071196

Korenblum C, Taylor RM, Fern LA, Hough R, Wickramasinghe B. Factors Affecting Psychosocial Distress in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: BRIGHTLIGHT Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Cohort Study Results. Cancers. 2025; 17(7):1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071196

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorenblum, Chana, Rachel M. Taylor, Lorna A. Fern, Rachael Hough, and Bethany Wickramasinghe. 2025. "Factors Affecting Psychosocial Distress in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: BRIGHTLIGHT Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Cohort Study Results" Cancers 17, no. 7: 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071196

APA StyleKorenblum, C., Taylor, R. M., Fern, L. A., Hough, R., & Wickramasinghe, B. (2025). Factors Affecting Psychosocial Distress in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: BRIGHTLIGHT Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Cohort Study Results. Cancers, 17(7), 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071196