Exploration of Predictive Factors for Acute Radiotherapy-Induced Gastro-Intestinal Symptoms in Prostate Cancer Patients

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Treatment and Follow-Up

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Candidate Predictors

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes

3.3. Interactions in the Relationship Between Systemic Inflammation and Patient-Reported GI Symptoms

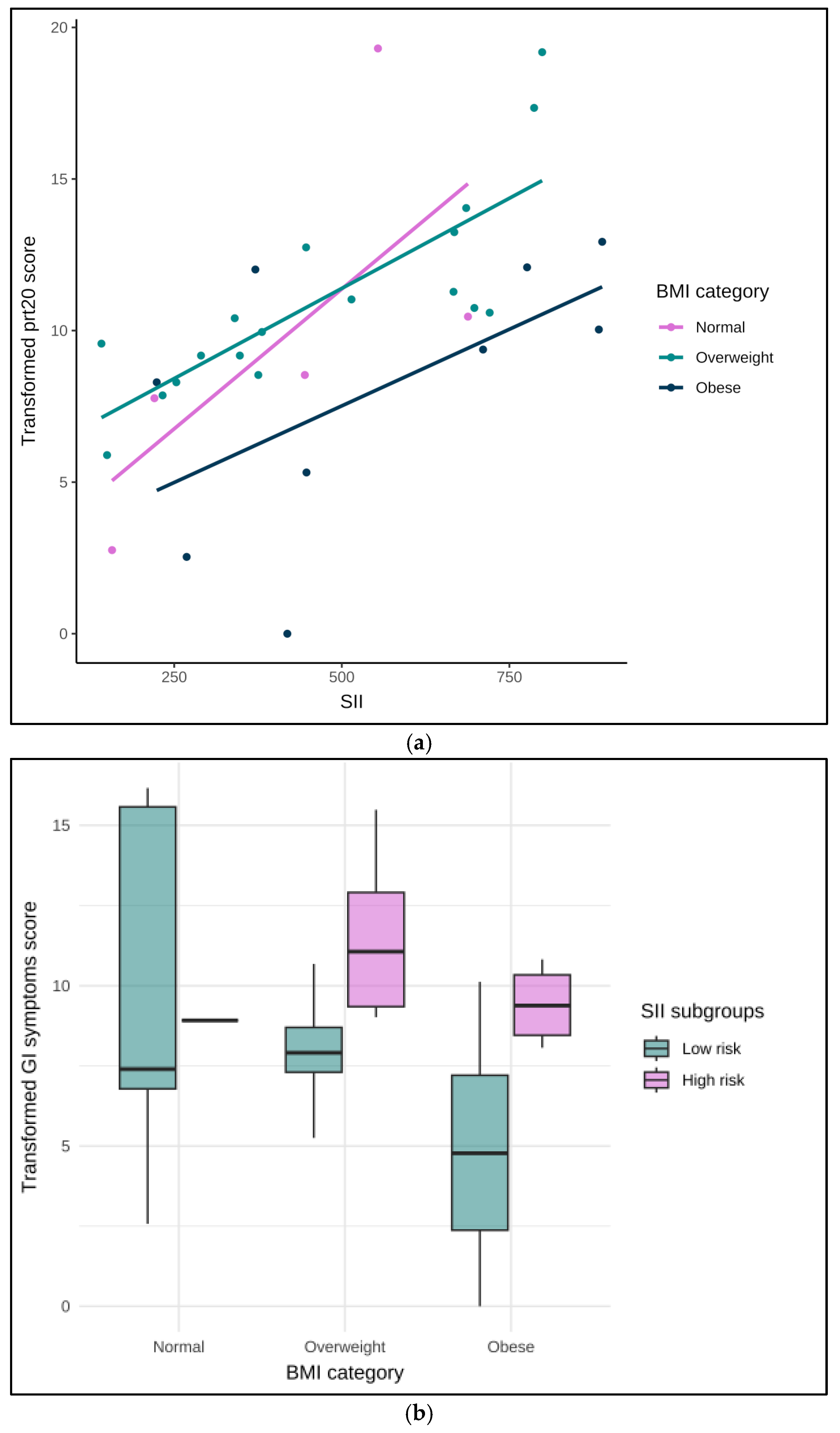

3.3.1. Interaction with BMI Categories

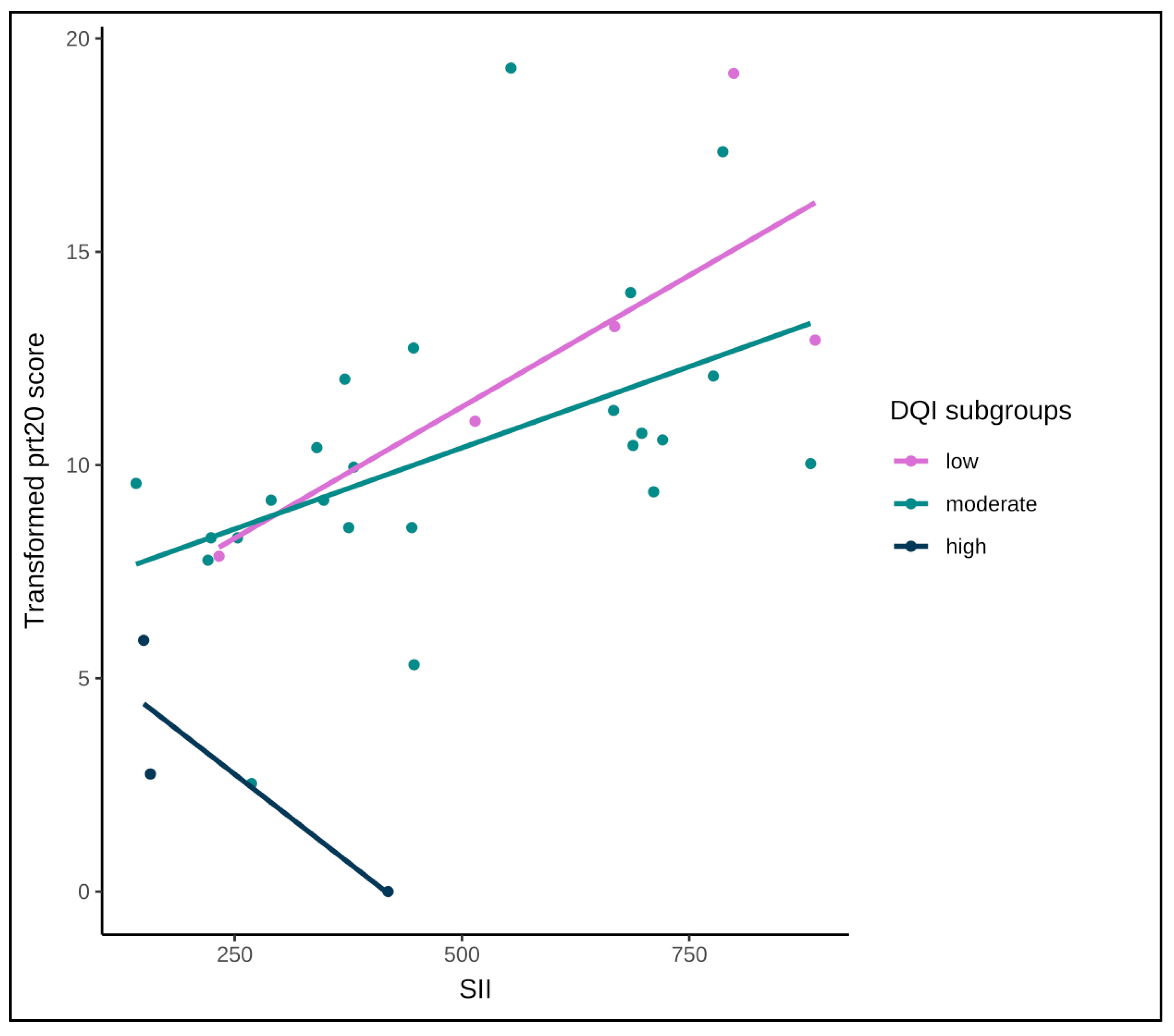

3.3.2. Interaction with Diet Quality

3.4. Clinician-Reported Toxicity

3.5. Integration of Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Clinical Interpretation

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADT | Androgen deprivation therapy |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criteria |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| b | Linear regression slope |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CROs | Clinician-reported outcomes |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CTCAE | Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events |

| CTV | Clinical target volume |

| DQI | Diet Quality Index |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EORTC | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer |

| GI | Gastro-Intestinal |

| IGRT | Image-guided radiation therapy |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MIM | Medical Image Merge |

| OAR | Organ At Risk |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PORT | Prostate/prostate bed only radiation therapy |

| PROs | Patient-reported outcomes |

| PRV | Planning organ at Risk Volume |

| PTV | Planning Target Volume |

| QLQ | Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RT | Radiation Therapy |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SIB | Simultaneous integrated boost |

| SII | Systemic immune-inflammation index |

| SMI | Skeletal Muscle Index |

| VMAT | Volumetric modulated arc therapy |

| WPRT | Whole-pelvis radiation therapy |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Dearnaley, D.; Syndikus, I.; Mossop, H.; Khoo, V.; Birtle, A.; Bloomfield, D.; Graham, J.; Kirkbride, P.; Logue, J.; Malik, Z.; et al. Conventional versus Hypofractionated High-Dose Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes of the Randomised, Non-Inferiority, Phase 3 CHHiP Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, C.N.; Lukka, H.; Gu, C.-S.; Martin, J.M.; Supiot, S.; Chung, P.W.M.; Bauman, G.S.; Bahary, J.-P.; Ahmed, S.; Cheung, P.; et al. Randomized Trial of a Hypofractionated Radiation Regimen for the Treatment of Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1884–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.A.; Colbert, L.; Nickleach, D.; Shelton, J.; Marcus, D.M.; Switchenko, J.; Rossi, P.J.; Godette, K.; Cooper, S.; Jani, A.B. Reduced Acute Toxicity Associated with the Use of Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy for the Treatment of Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2013, 3, e157–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini, G.; Pergolizzi, S. A Ten-Year-Long Update on Radiation Proctitis Among Prostate Cancer Patients Treated with Curative External Beam Radiotherapy. Vivo 2021, 35, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini, G.; Tripoli, A.; Molino, L.; Cacciola, A.; Lillo, S.; Parisi, S.; Umina, V.; Illari, S.I.; Marchese, V.A.; Cravagno, I.R.; et al. How Much Daily Image-Guided Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy Is Useful for Proctitis Prevention with Respect to Static Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy Supported by Topical Medications Among Localized Prostate Cancer Patients? Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikitas, J.; Jamshidian, P.; Tree, A.C.; Hall, E.; Dearnaley, D.; Michalski, J.M.; Lee, W.R.; Nguyen, P.L.; Sandler, H.M.; Catton, C.N.; et al. The Interplay between Acute and Late Toxicity among Patients Receiving Prostate Radiotherapy: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of Six Randomised Trials. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.E.; Chang, J.; Rosen, L.; Hartsell, W.; Tsai, H.; Chen, J.; Mishra, M.V.; Krauss, D.; Isabelle Choi, J.; Simone, C.B.; et al. Treatment Interruptions Affect Biochemical Failure Rates in Prostate Cancer Patients Treated with Proton Beam Therapy: Report from the Multi-Institutional Proton Collaborative Group Registry. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 25, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-M.; Ku, H.-Y.; Chang, T.-C.; Liu, T.-W.; Hong, J.-H. The Prognostic Impact of Overall Treatment Time on Disease Outcome in Uterine Cervical Cancer Patients Treated Primarily with Concomitant Chemoradiotherapy: A Nationwide Taiwanese Cohort Study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 85203–85213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lișcu, H.-D.; Antone-Iordache, I.-L.; Atasiei, D.-I.; Anghel, I.V.; Ilie, A.-T.; Emamgholivand, T.; Ionescu, A.-I.; Șandru, F.; Pavel, C.; Ultimescu, F. The Impact on Survival of Neoadjuvant Treatment Interruptions in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Patients. JPM 2024, 14, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach, M.S.; Showalter, T.N.; Ohri, N. Systematic Review of the Relationship between Acute and Late Gastrointestinal Toxicity after Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. Prostate Cancer 2015, 2015, 624736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemsbergen, W.D.; Peeters, S.T.H.; Koper, P.C.M.; Hoogeman, M.S.; Lebesque, J.V. Acute and Late Gastrointestinal Toxicity after Radiotherapy in Prostate Cancer Patients: Consequential Late Damage. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006, 66, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedlake, L.J.; Thomas, K.; Lalji, A.; Blake, P.; Khoo, V.S.; Tait, D.; Andreyev, H.J.N. Predicting Late Effects of Pelvic Radiotherapy: Is There a Better Approach? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 78, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyev, J. Gastrointestinal Complications of Pelvic Radiotherapy: Are They of Any Importance? Gut 2005, 54, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biran, A.; Bolnykh, I.; Rimmer, B.; Cunliffe, A.; Durrant, L.; Hancock, J.; Ludlow, H.; Pedley, I.; Rees, C.; Sharp, L. A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies of Chronic Bowel Symptoms in Cancer Survivors Following Pelvic Radiotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, S.; Thorsell, A.; Hedenström, P.; Rezapour, A.; Heden, L.; Banerjee, S.; Johansson, M.E.V.; Birchenough, G.; Toft Morén, A.; Gustavsson, K.; et al. Low-Grade Intestinal Inflammation Two Decades after Pelvic Radiotherapy. eBioMedicine 2023, 94, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holch, P.; Henry, A.M.; Davidson, S.; Gilbert, A.; Routledge, J.; Shearsmith, L.; Franks, K.; Ingleson, E.; Albutt, A.; Velikova, G. Acute and Late Adverse Events Associated with Radical Radiation Therapy Prostate Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review of Clinician and Patient Toxicity Reporting in Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 97, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, J.C.F.; Liu, K.C.K.; Pang, I.K.H.; Nicol, A.J.; Leung, V.W.S.; Cai, J.; Lee, S.W.Y. Predictive Factors for Gastrointestinal and Genitourinary Toxicities in Prostate Cancer External Beam Radiotherapy: A Scoping Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkett, G.K.B.; Wigley, C.A.; Aoun, S.M.; Portaluri, M.; Tramacere, F.; Livi, L.; Detti, B.; Arcangeli, S.; Lund, J.-A.; Kristensen, A.; et al. International Validation of the EORTC QLQ-PRT20 Module for Assessment of Quality of Life Symptoms Relating to Radiation Proctitis: A Phase IV Study. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCI. CTCAE v5.0; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maio, M.; Gallo, C.; Leighl, N.B.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Daniele, G.; Nuzzo, F.; Gridelli, C.; Gebbia, V.; Ciardiello, F.; De Placido, S.; et al. Symptomatic Toxicities Experienced During Anticancer Treatment: Agreement Between Patient and Physician Reporting in Three Randomized Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdyan, A.; Jassem, J. Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Outcomes of Radiotherapy: A Narrative Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 2284–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuccio, L.; Guido, A.; Andreyev, H.J.N. Management of Intestinal Complications in Patients with Pelvic Radiation Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 1326–1334.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prame Kumar, K.; Ooi, J.D.; Goldberg, R. The Interplay between the Microbiota, Diet and T Regulatory Cells in the Preservation of the Gut Barrier in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1291724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lewis, E.D.; Pae, M.; Meydani, S.N. Nutritional Modulation of Immune Function: Analysis of Evidence, Mechanisms, and Clinical Relevance. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. The Relationship between Nutrition and the Immune System. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1082500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güven, İ.E.; Başpınar, B.; Atalay, R. Relationship Between Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 33, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Lin, J.; Liu, L.; Xie, N.; Yu, H.; Deng, S.; Sun, Y. A Novel Nomogram Based on Inflammation Biomarkers for Predicting Radiation Cystitis in Patients with Local Advanced Cervical Cancer. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, X. Prognostic Value of the Pretreatment Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Patients with Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.; Kenny, A.M.; Taxel, P.; Lorenzo, J.A.; Duque, G.; Kuchel, G.A. Role of Endocrine-Immune Dysregulation in Osteoporosis, Sarcopenia, Frailty and Fracture Risk. Mol. Asp. Med. 2005, 26, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, F.; Rizzo, S.; Buwenge, M.; Arcelli, A.; Ferioli, M.; Macchia, G.; Deodato, F.; Cilla, S.; De Iaco, P.; Perrone, A.M.; et al. Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sarcopenia but Were Afraid to Ask: A Quick Guide for Radiation Oncologists (impAct oF saRcopeniA In raDiotherapy: The AFRAID Project). Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8513–8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catikkas, N.M.; Bahat, Z.; Oren, M.M.; Bahat, G. Older Cancer Patients Receiving Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review for the Role of Sarcopenia in Treatment Outcomes. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 1747–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protano, C.; Gallè, F.; Volpini, V.; De Giorgi, A.; Mazzeo, E.; Ubaldi, F.; Romano Spica, V.; Vitali, M.; Valeriani, F. Physical Activity in the Prevention and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment Dominates over Host Genetics in Shaping Human Gut Microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet Rapidly and Reproducibly Alters the Human Gut Microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumagai, T.; Rahman, F.; Smith, A.M. The Microbiome and Radiation Induced-Bowel Injury: Evidence for Potential Mechanistic Role in Disease Pathogenesis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonneau, M.; Elkrief, A.; Pasquier, D.; Paz Del Socorro, T.; Chamaillard, M.; Bahig, H.; Routy, B. The Role of the Gut Microbiome on Radiation Therapy Efficacy and Gastrointestinal Complications: A Systematic Review. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollà, M.; Panés, J. Radiation-Induced Intestinal Inflammation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, A.; Milliat, F.; Guipaud, O.; Benderitter, M. Inflammation and Immunity in Radiation Damage to the Gut Mucosa. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 123241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Liang, Y.; Tian, S.; Jin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, H. Radiation-Induced Intestinal Injury: Injury Mechanism and Potential Treatment Strategies. Toxics 2023, 11, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus 2022, 14, e22711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhang, A.; Li, Y. Association between Obesity and Systemic Immune Inflammation Index, Systemic Inflammation Response Index among US Adults: A Population-Based Analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Page, A.J.; Gill, T.K.; Melaku, Y.A. The Association between Diet Quality, Plant-Based Diets, Systemic Inflammation, and Mortality Risk: Findings from NHANES. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 2723–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuraiban, G.; Gibson, R.; Oude Griep, L. Associations of Systematic Inflammatory Markers with Diet Quality, Blood Pressure, and Obesity in the AIRWAVE Health Monitoring Study. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 3129–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty, Ú.M.; McNair, H.A.; Norman, A.R.; Miles, E.; Hooper, S.; Davies, M.; Lincoln, N.; Balyckyi, J.; Childs, P.; Dearnaley, D.P.; et al. Variability of Bladder Filling in Patients Receiving Radical Radiotherapy to the Prostate. Radiother. Oncol. 2006, 79, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salembier, C.; Villeirs, G.; De Bari, B.; Hoskin, P.; Pieters, B.R.; Van Vulpen, M.; Khoo, V.; Henry, A.; Bossi, A.; De Meerleer, G.; et al. ESTRO ACROP Consensus Guideline on CT- and MRI-Based Target Volume Delineation for Primary Radiation Therapy of Localized Prostate Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 127, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Pra, A.; Dirix, P.; Khoo, V.; Carrie, C.; Cozzarini, C.; Fonteyne, V.; Ghadjar, P.; Gomez-Iturriaga, A.; Panebianco, V.; Zapatero, A.; et al. ESTRO ACROP Guideline on Prostate Bed Delineation for Postoperative Radiotherapy in Prostate Cancer. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 41, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.R.; Tree, A.C.; Alexander, E.J.; Sohaib, A.; Hazell, S.; Thomas, K.; Gunapala, R.; Parker, C.C.; Huddart, R.A.; Gao, A.; et al. Standard and Hypofractionated Dose Escalation to Intraprostatic Tumor Nodules in Localized Prostate Cancer: Efficacy and Toxicity in the DELINEATE Trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 106, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.; Maitre, P.; Kannan, S.; Panigrahi, G.; Krishnatry, R.; Bakshi, G.; Prakash, G.; Pal, M.; Menon, S.; Phurailatpam, R.; et al. Prostate-Only Versus Whole-Pelvic Radiation Therapy in High-Risk and Very High-Risk Prostate Cancer (POP-RT): Outcomes From Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, K.A.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Every Step Counts: Synthesising Reviews Associating Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour with Clinical Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e764–e772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, M.B.; Pavlin, T.; Čavka, L.; Ribnikar, D.; Spazzapan, S.; Templeton, A.J.; Šeruga, B. The Trajectory of Sarcopenia Following Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2023, 14, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.J.; McSweeney, D.M.; Choudhury, A.; Weaver, J.; Price, G.; McWilliam, A. The Prognostic Significance of Sarcopenia in Patients Treated with Definitive Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review. Radiother. Oncol. 2025, 203, 110663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, T. Prognostic Significance of Pretreatment Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Patients with Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutter Snyder, D.; Sloane, R.; Haines, P.S.; Miller, P.; Clipp, E.C.; Morey, M.C.; Pieper, C.; Cohen, H.; Demark-Wahnefried, W. The Diet Quality Index-Revised: A Tool to Promote and Evaluate Dietary Change among Older Cancer Survivors Enrolled in a Home-Based Intervention Trial{A Figure Is Presented}. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conseil Supérieur de la Santé. Risques Liés à La Consommation d’alcool; Conseil Supérieur de la Santé: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2018; p. N 9438. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Craig, C.L.; Brown, W.J.; Clemes, S.A.; De Cocker, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Hatano, Y.; Inoue, S.; Matsudo, S.M.; Mutrie, N.; et al. How Many Steps/Day Are Enough? For Adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Birdsell, L.; MacDonald, N.; Reiman, T.; Clandinin, M.T.; McCargar, L.J.; Murphy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Sawyer, M.B.; Baracos, V.E. Cancer Cachexia in the Age of Obesity: Skeletal Muscle Depletion Is a Powerful Prognostic Factor, Independent of Body Mass Index. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Depotte, L.; Caroux, M.; Gligorov, J.; Canouï-Poitrine, F.; Belkacemi, Y.; De La Taille, A.; Tournigand, C.; Kempf, E. Association between Overweight, Obesity, and Quality of Life of Patients Receiving an Anticancer Treatment for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2023, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini, G.; Zagardo, V.; Valenti, V.; Aiello, D.; Federico, M.; Fazio, I.; Harikar, M.M.; Marchese, V.A.; Illari, S.I.; Viola, A.; et al. Towards Personalization of Planning Target Volume Margins Fitted to the Abdominal Adiposity in Localized Prostate Cancer Patients Receiving Definitive or Adjuvant/Salvage Radiotherapy: Suggestive Data from an ExacTrac vs. CBCT Comparison. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 4077–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, T.A.; Green, J.T.; Beresford, M.; Wedlake, L.; Burden, S.; Davidson, S.E.; Lal, S.; Henson, C.C.; Andreyev, H.J.N. Interventions to Reduce Acute and Late Adverse Gastrointestinal Effects of Pelvic Radiotherapy for Primary Pelvic Cancers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, CD012529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreou, L.; Burrows, T.; Surjan, Y. The Effect of Nutritional Interventions Involving Dietary Counselling on Gastrointestinal Toxicities in Adults Receiving Pelvic Radiotherapy—A Systematic Review. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 2021, 68, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerassy-Vainberg, S.; Blatt, A.; Danin-Poleg, Y.; Gershovich, K.; Sabo, E.; Nevelsky, A.; Daniel, S.; Dahan, A.; Ziv, O.; Dheer, R.; et al. Radiation Induces Proinflammatory Dysbiosis: Transmission of Inflammatory Susceptibility by Host Cytokine Induction. Gut 2018, 67, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, K.; Chaudhari, D.; Dhotre, D.; Shouche, Y.; Saroj, S. Restoration of Dysbiotic Human Gut Microbiome for Homeostasis. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Bäckhed, F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hille, A.; Schmidt-Giese, E.; Hermann, R.M.; Herrmann, M.K.A.; Rave-Fränk, M.; Schirmer, M.; Christiansen, H.; Hess, C.F.; Ramadori, G. A Prospective Study of Faecal Calprotectin and Lactoferrin in the Monitoring of Acute Radiation Proctitis in Prostate Cancer Treatment. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, W.; Dong, M.; Sasson, G.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; Espin-Garcia, O.; Lee, S.-H.; Neustaeter, A.; Smith, M.I.; Leibovitzh, H.; Guttman, D.S.; et al. Mediterranean-Like Dietary Pattern Associations with Gut Microbiome Composition and Subclinical Gastrointestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, E.; Antolin, M.; Guarner, F.; Verges, R.; Giralt, J.; Malagelada, J.-R. Faecal DNA and Calprotectin as Biomarkers of Acute Intestinal Toxicity in Patients Undergoing Pelvic Radiotherapy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini, G.; Cacciola, A.; Parisi, S.; Lillo, S.; Molino, L.; Tamburella, C.; Davi, V.; Napoli, I.; Platania, A.; Settineri, N.; et al. Curative Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients with Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: The Prognostic Role of Sarcopenia. Vivo 2021, 35, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartrell, R.; Qiao, J.; Kiss, N.; Faragher, I.; Chan, S.; Baird, P.N.; Yeung, J.M. Can Sarcopenia Predict Survival in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Patients? ANZ J. Surg. 2023, 93, 2166–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadducci, A.; Cosio, S. The Prognostic Relevance of Computed Tomography-Assessed Skeletal Muscle Index and Skeletal Muscle Radiation Attenuation in Patients with Gynecological Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Jin, X. The Cachexia Index as a Prognostic Indicator in Patients with Cervical Cancer Treated with Radiotherapy: A Retrospective Study. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.; Choudhury, A.; McWilliam, A.; McSweeney, D.M.; Price, G.; Weaver, J. Sarcopenia Does Not Predict Increased Acute or Late Radiotherapy Related Toxicities in Prostate Cancer Patients. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 38, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbury, L.D.; Beaudart, C.; Bruyère, O.; Cauley, J.A.; Cawthon, P.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Curtis, E.M.; Ensrud, K.; Fielding, R.A.; Johansson, H.; et al. Recent Sarcopenia Definitions—Prevalence, Agreement and Mortality Associations among Men: Findings from Population-Based Cohorts. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, H.C.; Denison, H.J.; Martin, H.J.; Patel, H.P.; Syddall, H.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. A Review of the Measurement of Grip Strength in Clinical and Epidemiological Studies: Towards a Standardised Approach. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, A.L.K.; Knight, K.; Panettieri, V.; Dimmock, M.; Tuan, J.K.L.; Tan, H.Q.; Wright, C. Dose-Volume Analysis of Planned versus Accumulated Dose as a Predictor for Late Gastrointestinal Toxicity in Men Receiving Radiotherapy for High-Risk Prostate Cancer. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 23, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammers, J.; Lindsay, D.; Narayanasamy, G.; Sud, S.; Tan, X.; Dooley, J.; Marks, L.B.; Chen, R.C.; Das, S.K.; Mavroidis, P. Evaluation of the Clinical Impact of the Differences between Planned and Delivered Dose in Prostate Cancer Radiotherapy Based on CT-on-rails IGRT and Patient-reported Outcome Scores. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2023, 24, e13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73 (65–78) | |

| Tobacco exposure | ||

| Never exposed | 17 (53%) | |

| Previously or currently exposed | 15 (47%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Within recommendations | 18 (56%) | |

| Exceed recommendations | 14 (44%) | |

| Daily step count (n) | 7276 (4515–10,787) | |

| Physical activity levels [daily step count] | ||

| Inactive [≤5158] | 11 (34%) | |

| Low to moderately active [5159–9915] | 10 (31%) | |

| Active [≥9916] | 11 (34%) | |

| Constipation | ||

| Known chronic constipation | 9 (28%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.0 (26.3–30.1) | |

| BMI category | ||

| Normal [18.5–24.9] | 5 (16%) | |

| Overweight [25.0–29.9] | 18 (56%) | |

| Obese [≥30.0] | 9 (28%) | |

| Waist circumference [cm] | ||

| Low/medium CV risk [<102] | 13 (41%) | |

| High CV risk [≥102] | 19 (59%) | |

| SMI (cm2/m2) | 52 (46, 60) | |

| Sarcopenia on CT | 15 (47%) | |

| SII | 446 (279–693) | |

| SII risk group | ||

| Low risk [<576] | 20 (63%) | |

| High risk [≥576] | 12 (38%) | |

| DQI | 65 (60–70) | |

| DQI level | ||

| Low [≤55] | 5 (16%) | |

| Moderate [56–75] | 24 (75%) | |

| High [≥76] | 3 (9.4%) | |

| Previous prostatectomy | 16 (50%) | |

| Concomitant ADT | 29 (91%) | |

| RT field size | ||

| PORT | 5 (16%) | |

| WPRT | 27 (84%) | |

| Predictor | Mean ± SD | Univariable b ± SE | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (n) | ||||||||

| Total (32) | 10.0 ± 4.21 | |||||||

| Tobacco exposure | 0.083 ' | |||||||

| Non-exposed (17) | 8.80 ± 4.11 | Ref | ||||||

| Exposed (15) | 11.4 ± 4.01 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | ||||||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.09 ' ✣ | |||||||

| Within recommendations (18) | 9.09 ± 3.89 | Ref | ||||||

| Exceed recommendations (14) | 11.2 ± 4.44 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | ||||||

| Constipation history | 0.02 * ✣ | |||||||

| No (23) | 11.0 ± 3.99 | Ref | ||||||

| Yes (9) | 7.48 ± 3.84 | −3.5 ± 1.55 | ||||||

| BMI category | 0.22 | |||||||

| Normal (5) | 9.76 ± 6.04 | Ref | ||||||

| Overweight (18) | 11.1 ± 3.29 | 1.3 ± 2.1 | (0.81) | |||||

| Obese (9) | 8.06 ± 4.53 | −1.7 ± 2.3 | (0.74) | |||||

| Waist circumference | 0.94 | |||||||

| Low/medium CV risk (13) | 10.1 ± 3.25 | Ref | ||||||

| High CV risk (19) | 9.97 ± 4.84 | −0.1 ± 1.5 | ||||||

| Sarcopenia on CT | 0.93 | |||||||

| No (17) | 9.95 ± 4.31 | Ref | ||||||

| Yes (15) | 10.1 ± 4.24 | 0.14 ± 1.5 | ||||||

| Physical activity level | 0.51 | |||||||

| Inactive (11) | 8.83 ± 5.30 | Ref | ||||||

| Low to moderately active (10) | 10.4 ± 1.74 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | ||||||

| Active (11) | 10.9 ± 4.65 | 2.1 ± 1.8 | ||||||

| SII risk group | 0.005 ** | |||||||

| Low risk (20) | 8.46 ± 4.10 | Ref | ||||||

| High risk (12) | 12.6 ± 3.01 | 4.2 ± 1.4 | ||||||

| DQI level | 0.002 ** | |||||||

| Low (5) | 12.8 ± 4.14 | Ref | ||||||

| Moderate (24) | 10.3 ± 3.41 | −2.5 ± 1.7 | (0.32) | |||||

| High (3) | 2.88 ± 2.95 | −9.9 ± 2.6 | (0.001) ** | |||||

| Previous prostatectomy | 0.72 | |||||||

| No (16) | 9.75 ± 5.04 | Ref | ||||||

| Yes (16) | 10.3 ± 3.32 | 0.5 ± 1.5 | ||||||

| Concomitant ADT | 0.26 | |||||||

| No (3) | 7.38 ± 1.79 | Ref | ||||||

| Yes (29) | 10.3 ± 4.31 | 2.9 ± 2.5 | ||||||

| RT field | 0.053 ' | |||||||

| PORT (5) | 6.69 ± 2.58 | Ref | ||||||

| WPRT (27) | 10.6 ± 4.19 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | ||||||

| Age | −0.006 ± 0.09 | 0.95 | ||||||

| Step (n) | 0.0001 ± 0.0002 | 0.57 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.37 | ||||||

| SMI (cm2/m2) | −0.01 ± 0.09 | 0.90 | ||||||

| SII | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 0.0004 *** | ||||||

| DQI | −0.16 ± 0.09 | 0.057 ' | ||||||

| Predictor | Slope | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (n) | Adj b ± SE | p | |||

| Tobacco exposure | 0.38 | ||||

| Non-exposed (17) | Ref | ||||

| Exposed (15) | 1.1 ± 1.20 | ||||

| Constipation history | 0.22 | ||||

| No (23) | Ref | ||||

| Yes (9) | −1.7 ± 1.39 | ||||

| BMI category | 0.02 * | ||||

| Normal (5) | Ref | ||||

| Overweight (18) | −1.2 ± 1.63 | (0.47) | |||

| Obese (9) | −4.8 ± 1.80 | (0.015) * | |||

| Previous prostatectomy | 0.24 | ||||

| No (16) | Ref | ||||

| Yes (16) | 1.5 ± 1.21 | ||||

| Concomitant ADT | 0.96 | ||||

| No (3) | Ref | ||||

| Yes (29) | 0.14 ± 3.01 | ||||

| RT field | 0.71 | ||||

| PORT (5) | Ref | ||||

| WPRT (27) | 0.9 ± 2.40 | ||||

| DQI level | 0.18 | ||||

| Low (5) | Ref | ||||

| Moderate (24) | −0.7 ± 1.63 | 0.67 | |||

| High (3) | −4.7 ± 2.69 | 0.097 | |||

| SII | 0.008 ± 0.003 | 0.018 * | |||

| Predictor | Slope | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (n) | Adj b ± SE | p | |||

| BMI category | 0.02 * | ||||

| Normal (5) | Ref | ||||

| Overweight (18) | −0.21 ± 1.45 | (0.89) | |||

| Obese (9) | −3.6 ± 1.58 | (0.031) * | |||

| DQI level | 0.03 * | ||||

| Low (5) | Ref | ||||

| Moderate (24) | −1.0 ± 1.44 | 0.49 | |||

| High (3) | −6.0 ± 2.30 | 0.015 * | |||

| SII | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 0.001 ** | |||

| Predictor | ≥Grade 2 GI Toxicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (n) | % | OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| Tobacco exposure | 0.51 | ||||

| Non-exposed (17) | 35.3 | 1 | |||

| Exposed (15) | 46.7 | 1.60 | (0.39; 6.88) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.62 | ||||

| Within recommendations (18) | 44.4 | 1 | |||

| Exceed recommendations (14) | 35.7 | 0.69 | (0.16; 2.89) | ||

| Constipation history | 0.29 | ||||

| No (23) | 34.8 | 1 | |||

| Yes (9) | 55.6 | 2.34 | (0.49; 12.0) | ||

| BMI category | 0.07 ' | ||||

| Normal (5) | 60.0 | 1 | |||

| Overweight (18) | 50.0 | 0.67 | (0.07; 4.99) | (0.69) | |

| Obese (9) | 11.1 | 0.08 | (0.003; 1.03) | (0.08) ' | |

| Abdominal waist | 0.60 | ||||

| Low/medium CV risk (13) | 46.2 | 1 | |||

| High CV risk (19) | 36.8 | 0.68 | (0.16; 2.89) | ||

| Sarcopenia on CT | 0.95 | ||||

| No (17) | 41.2 | 1 | |||

| Yes (15) | 40.0 | 0.95 | (0.23; 3.96) | ||

| Physical activity level | 0.77 | ||||

| Inactive (11) | 36.4 | 1 | |||

| Low to moderately active (10) | 50.0 | 1.75 | (0.31; 10.7) | (0.53) | |

| Active (11) | 36.4 | 1.00 | (0.17; 5.88) | (1.00) | |

| SII risk group | 0.12 ' | ||||

| Low risk (20) | 30.0 | 1 | |||

| High risk (12) | 58.3 | 3.27 | (0.75; 15.6) | ||

| DQI level | 0.04 * | ||||

| Low (5) | 80.0 | 1 | |||

| Moderate (24) | 37.5 | 0.15 | (0.007; 1.21) | (0.11) | |

| High (3) | 0.0 | NA | (NA; NA) | (0.99) | |

| Previous prostatectomy | 0.28 | ||||

| No (16) | 31.2 | 1 | |||

| Yes (16) | 50.0 | 2.20 | (0.53; 9.84) | ||

| Concomitant ADT | 0.99 | ||||

| No (3) | 0.0 | 1 | |||

| Yes (29) | 44.8 | NA | (NA; NA) | ||

| RT field | >0.99 | ||||

| PORT (5) | 0.0 | 1 | |||

| WPRT (27) | 48.1 | NA | (NA; NA) | ||

| Predictor | ≥Grade 2 GI Toxicity | Likelihood Ratio Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories (n) | % | Adj OR | (95% CI) | p | |

| BMI category | 0.08 | ||||

| Normal (5) | 60.0 | 1 | |||

| Overweight (18) | 50.0 | 0.27 | (0.02; 2.24) | (0.24) | |

| Obese (9) | 11.1 | 0.04 | (0.0009; 0.57) | (0.02 *) | |

| SII risk group | 0.06 | ||||

| Low risk (20) | 30.0 | 1 | |||

| High risk (12) | 58.3 | 9.75 | (0.64; 27.5) | (0.15) | |

| DQI level | 0.29 | ||||

| Low (5) | 80.0 | 1 | |||

| Moderate (24) | 37.5 | 0.19 | (0.015; 1.48) | (0.12) | |

| High (3) | 0.0 | 0.04 | (0.0002; 1.27) | (0.07) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Bruyn, P.; Klass, M.; Van Muylem, A.; Jullian, N.; Otte, F.-X.; Diamand, R.; Preiser, J.-C. Exploration of Predictive Factors for Acute Radiotherapy-Induced Gastro-Intestinal Symptoms in Prostate Cancer Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244035

De Bruyn P, Klass M, Van Muylem A, Jullian N, Otte F-X, Diamand R, Preiser J-C. Exploration of Predictive Factors for Acute Radiotherapy-Induced Gastro-Intestinal Symptoms in Prostate Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244035

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Bruyn, Pauline, Malgorzata Klass, Alain Van Muylem, Nicolas Jullian, François-Xavier Otte, Romain Diamand, and Jean-Charles Preiser. 2025. "Exploration of Predictive Factors for Acute Radiotherapy-Induced Gastro-Intestinal Symptoms in Prostate Cancer Patients" Cancers 17, no. 24: 4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244035

APA StyleDe Bruyn, P., Klass, M., Van Muylem, A., Jullian, N., Otte, F.-X., Diamand, R., & Preiser, J.-C. (2025). Exploration of Predictive Factors for Acute Radiotherapy-Induced Gastro-Intestinal Symptoms in Prostate Cancer Patients. Cancers, 17(24), 4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17244035