Screening HCC Patients Who Can Benefit from the Sequential Treatment of Conversion Therapy and Radical Surgery and Constructing a Predictive Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Data Collection and Follow-Up

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Baseline Data

3.2. Screening of Independent Risk Factors

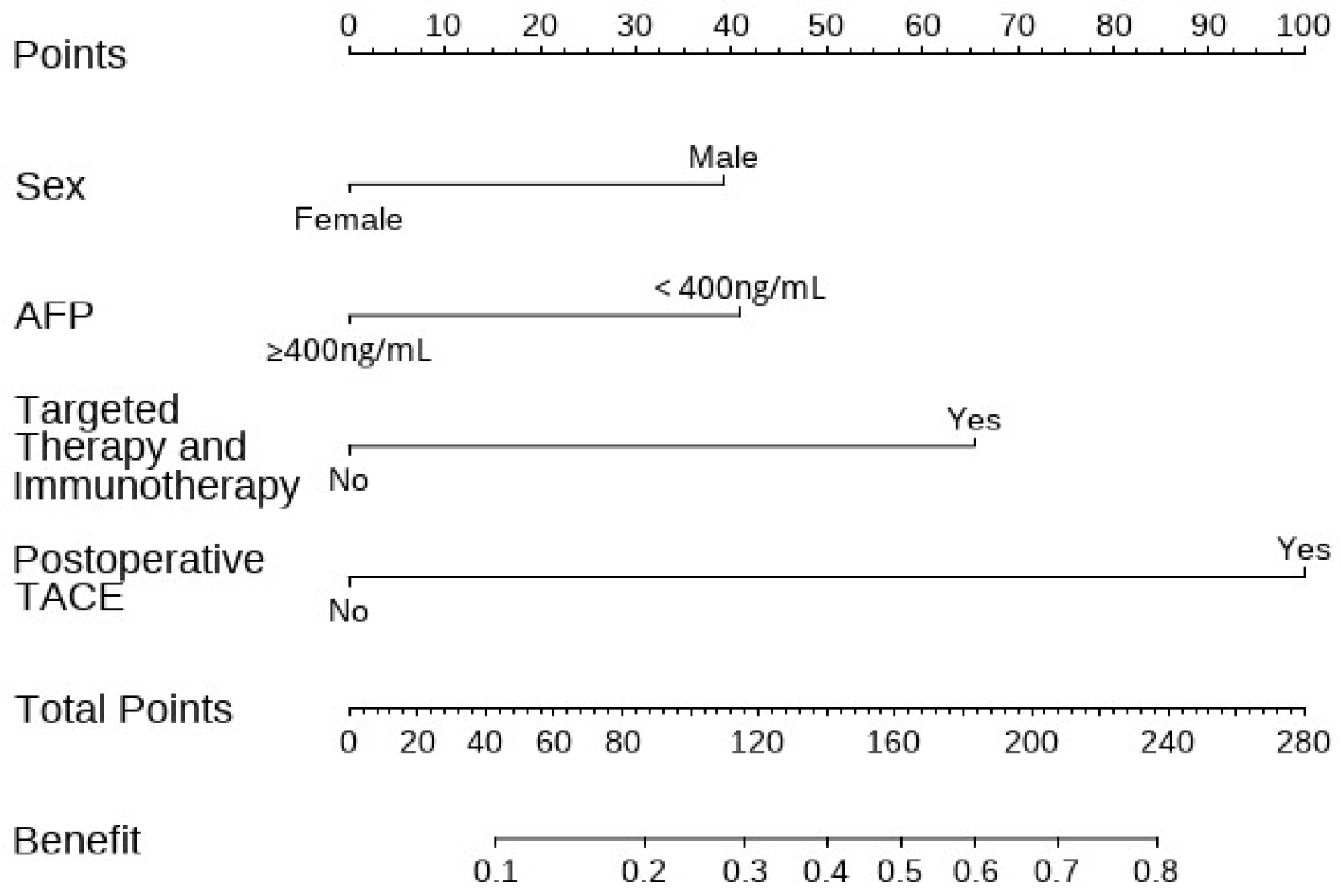

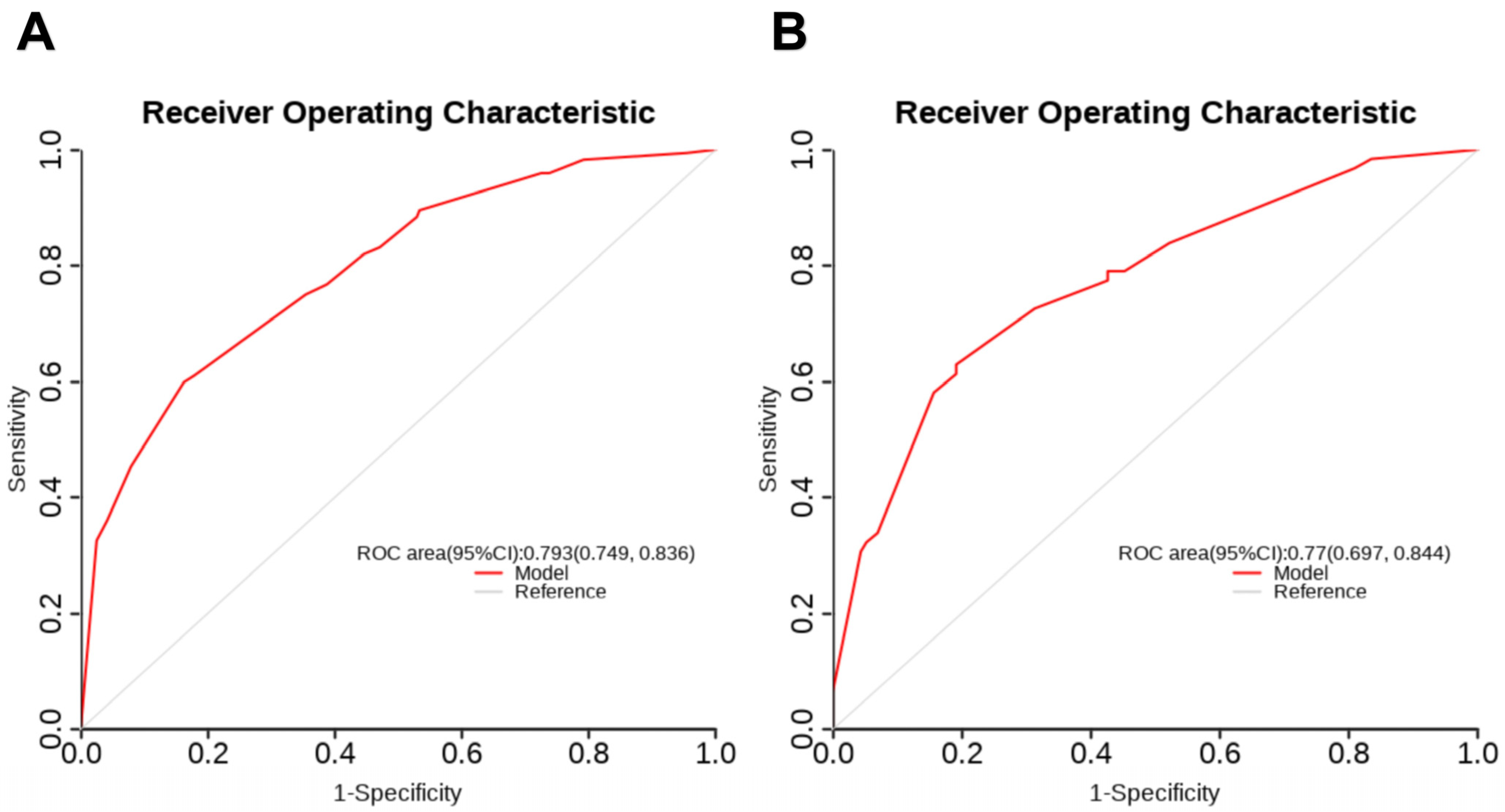

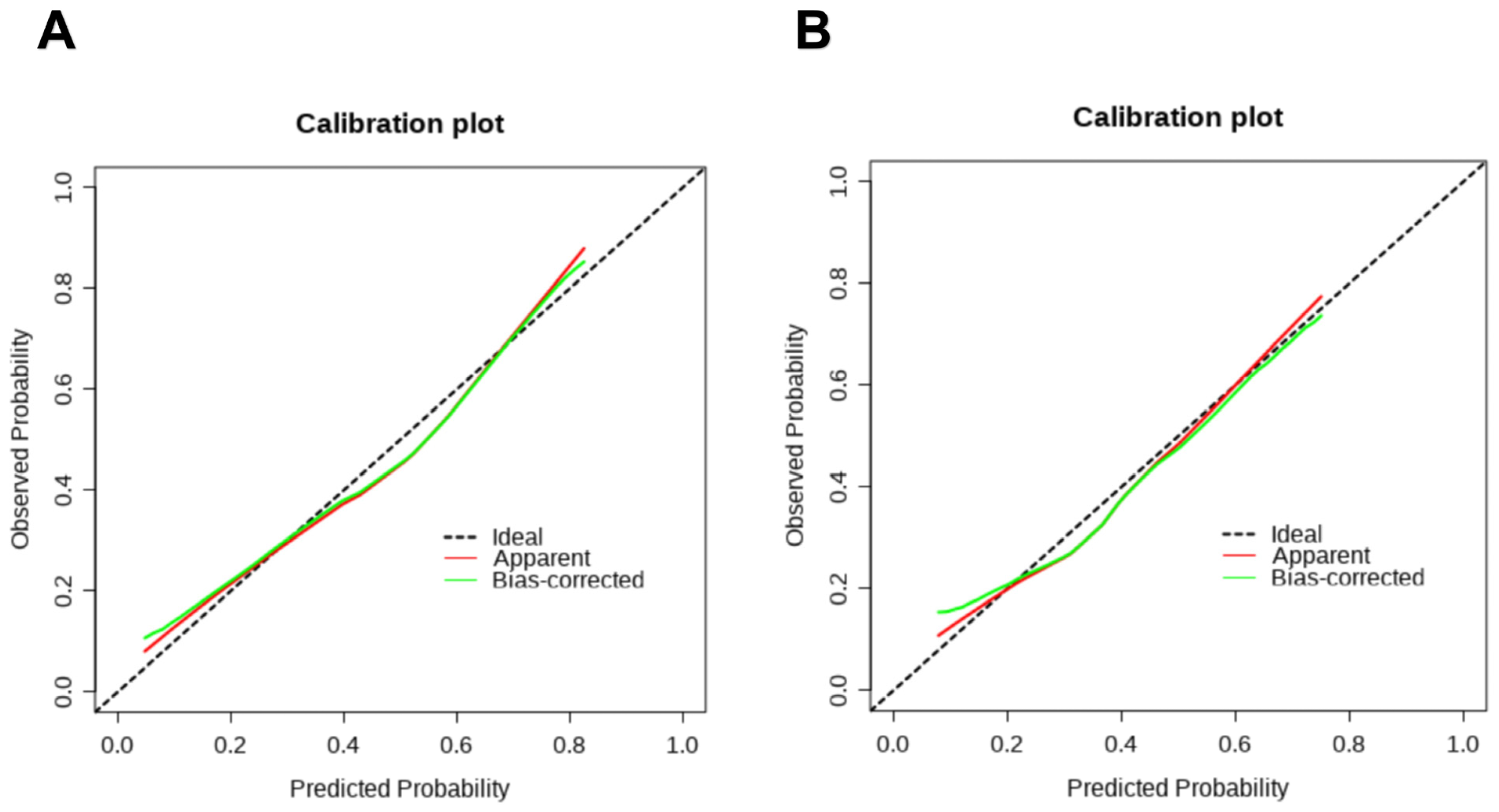

3.3. Construction and Validation of the Nomogram

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, E.Y.; Danpanichkul, P.; Yong, J.N.; Yu, Z.; Tan, D.J.H.; Lim, W.H.; Koh, B.; Lim, R.Y.Z.; Tham, E.K.J.; Mitra, K.; et al. Liver cancer in 2021: Global Burden of Disease study. J. Hepatol. 2024, 82, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Meyer, T.; Sapisochin, G.; Salem, R.; Saborowski, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2022, 400, 1345–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.J.H.; Ng, C.H.; Lin, S.Y.; Pan, X.H.; Tay, P.; Lim, W.H.; Teng, M.; Syn, N.; Lim, G.; Yong, J.N.; et al. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, C.T.J.; Rajendran, L.; Li, Z.; Banz, V.; Vogel, A.; O’KAne, G.M.; Chan, A.C.-Y.; Sapisochin, G. Precision surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Ueshima, K.; Saeki, I.; Ishikawa, T.; Inaba, Y.; Morimoto, N.; Aikata, H.; Tanabe, N.; Wada, Y.; Kondo, Y.; et al. A Phase 2, Prospective, Multicenter, Single-Arm Trial of Transarterial Chemoembolization Therapy in Combination Strategy with Lenvatinib in Patients with Unresectable Intermediate-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma: TACTICS-L Trial. Liver Cancer 2023, 13, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, K.; Zeng, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J.; Hu, X.; Chao, M. Bicarbonate-integrated transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in real-world hepatocellular carcinoma. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.L.; Chiu, K.W.H.; Chan, K.S.K.; Lee, F.A.S.; Li, J.C.B.; Wan, C.W.S.; Dai, W.C.; Lam, T.C.; Chen, W.; Wong, N.S.M.; et al. Sequential transarterial chemoembolisation and stereotactic body radiotherapy followed by immunotherapy as conversion therapy for patients with locally advanced, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (START-FIT): A single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-L.; Ye, L.; Zeng, F.-J.; Liu, J.; Yao, H.-B.; Nong, J.-L.; Liu, S.-P.; Peng, N.; Li, W.-F.; Wu, P.-S.; et al. Erratum: Multicenter, retrospective GUIDANCE001 study comparing transarterial chemoembolization with or without tyrosine kinase and immune checkpoint inhibitors as conversion therapy to treat unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Survival benefit in intermediate or advanced, but not early, stages. Hepatology 2025, 82, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Song, T. Conversion therapy and maintenance therapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci. Trends 2021, 15, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Chan, S.; Dawson, L.; Kelley, R.; Llovet, J.; Meyer, T.; Ricke, J.; Rimassa, L.; Sapisochin, G.; Vilgrain, V.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Kendall, B.J.; El-Serag, H.B.; Thrift, A.P.; A Macdonald, G. Hepatocellular and extrahepatic cancer risk in people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Zuo, B.; Huang, L.; You, X.; Liu, T.; Hao, J.; Yuan, C.; Yang, C.; Lau, W.Y.; Zhang, Y. Real-world efficacy and safety of TACE-HAIC combined with TKIs and PD-1 inhibitors in initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 137, 112492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnik, K.; Bartczak, T.; Krzyziński, M.; Korzeniowski, K.; Lamparski, K.; Węgrzyn, P.; Lam, E.; Bartkowiak, M.; Wróblewski, T.; Mech, K.; et al. WAW-TACE: A Hepatocellular Carcinoma Multiphase CT Dataset with Segmentations, Radiomics Features, and Clinical Data. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, e240296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-J.; He, M.-K.; Chen, H.-W.; Fang, W.-Q.; Zhou, Y.-M.; Xu, L.; Wei, W.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Guo, Y.; Guo, R.-P.; et al. Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin Versus Transarterial Chemoembolization for Large Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.-K.; Yang, L.-F.; Chen, Y.-F.; Chen, Z.-W.; Lu, H.; Shen, X.-Y.; Chi, M.-H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.-F.; et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation combined with lenvatinib plus camrelizumab as conversion therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A single-arm, multicentre, prospective study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 67, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, W.; Lei, F.; Peng, M.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Estrogen Induces LCAT to Maintain Cholesterol Homeostasis and Suppress Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Lin, S.; Ran, W.; Zhu, L.; Tang, C.; Wang, X. Sex steroid axes in determining male predominance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2022, 555, 216037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, N.E.; Murphy, C.C.; Yopp, A.C.; Tiro, J.; Marrero, J.A.; Singal, A.G. Sex disparities in presentation and prognosis of 1110 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Piao, M.; Xun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ning, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Biomarkers and prognostic factors of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-based therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Ma, W. Biomarker discovery in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) for personalized treatment and enhanced prognosis. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2024, 79, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, R.; Wei, Q.; Xu, X. The Landscape Of Alpha Fetoprotein In Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Where Are We? Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Geng, H.; Zhu, A.X.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Fan, J.; Wang, C.; Gao, Q. Precision treatment in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; He, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hua, S. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Signaling pathways, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Medcomm 2024, 5, e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.; Obi, S.; Zhou, J.; Tateishi, R.; Qin, S.; Zhao, H.; Otsuka, M.; Ogasawara, S.; George, J.; Chow, P.K.H.; et al. APASL clinical practice guidelines on systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma-2024. Hepatol. Int. 2024, 18, 1661–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, C.; Shen, X.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, G.; Song, X.; Huang, T.; Yang, J. Effect of transarterial chemoembolization as postoperative adjuvant therapy for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: A multicenter cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, Z. Preoperative Versus Postoperative Transarterial Chemoembolization on Prognosis of Large Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 6231–6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, Z.; Zhu, T.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; et al. Adjuvant TACE Improves Prognosis After Resection in Dual-Phenotype Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2025, 12, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Development Set (n = 412) | Validation Set (n = 177) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 342 (83.0%) | 153 (86.4%) | 0.297 |

| Female | 70 (17.0%) | 24 (13.6%) | ||

| Age | 54 ± 11 | 53 ± 11 | 0.329 | |

| BCLC stage | A | 128 (31.1%) | 54 (30.5%) | 0.893 |

| B/C | 284 (68.9%) | 123 (69.5%) | ||

| Child–Pugh score | A | 407 (98.8%) | 174 (98.3%) | 0.644 |

| B | 5 (1.2%) | 3 (1.7%) | ||

| Tumor number | Single | 127 (30.8%) | 60 (33.9%) | 0.463 |

| Multiple | 285 (69.2%) | 117 (66.1%) | ||

| Max. tumor size (mm) | 62 (40–99) | 59 (41–89) | 0.895 | |

| AFP ( ≥ 400ng/mL) | No | 276 (67.0%) | 112 (63.3%) | 0.383 |

| Yes | 136 (33.0%) | 65 (36.7%) | ||

| ALT (U/L) | 38 (26–60) | 38 (26–59) | 0.471 | |

| AST (U/L) | 44 (31–71) | 42 (30–72) | 0.635 | |

| TBIL (umol/L) | 13.2 (9.5–19.1) | 12.3 (8.8–18.6) | 0.105 | |

| PNI | 46.7 (43.5–50.6) | 46.9 (44.3–50.9) | 0.465 | |

| Preoperative TACE number | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 0.498 | |

| Tumor differentiation | Poor/Moderate | 281 (68.2%) | 115 (65.0%) | 0.444 |

| Good | 131 (31.8%) | 62 (35.0%) | ||

| MVI | 0 | 296 (71.8%) | 117 (66.1%) | 0.270 |

| 1 | 100 (24.3%) | 49 (27.7%) | ||

| 2 | 16 (3.9%) | 11 (6.2%) | ||

| Targeted therapy and immunotherapy | No | 209 (50.7%) | 106 (59.9%) | 0.041 |

| Yes | 203 (49.3%) | 71 (40.1%) | ||

| Postoperative TACE | No | 227 (55.1%) | 103 (58.2%) | 0.488 |

| Yes | 185 (44.9%) | 74 (41.8%) | ||

| Benefit | No | 240 (58.3%) | 115 (65.0%) | 0.127 |

| Yes | 172 (41.7%) | 62 (35.0%) | ||

| Status | Alive | 57 (13.8%) | 37 (20.9%) | 0.032 |

| Dead | 355 (86.2%) | 140 (79.1%) | ||

| OS (months) | 22.0 (15.0–36.0) | 19 (14.0–32.5) | 0.113 | |

| Variables | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Sex (Male) | 2.000 (1.142, 3.504) | 0.015 | 2.000 (1.018, 3.931) | 0.044 |

| Age | 0.996 (0.979, 1.013) | 0.631 | ||

| BCLC stage (B/C) | 0.449 (0.287, 0.702) | <0.001 | 0.666 (0.298, 1.488) | 0.321 |

| Child–Pugh score (B) | 0.345 (0.038, 3.114) | 0.343 | ||

| Tumor number (multiple) | 0.589 (0.381, 0.912) | 0.018 | 1.154 (0.525, 2.538) | 0.722 |

| Max. tumor size | 0.986 (0.980, 0.992) | <0.001 | 0.994 (0.986, 1.002) | 0.130 |

| AFP ( ≥ 400ng/mL) | 0.478 (0.309, 0.739) | 0.001 | 0.533 (0.313, 0.907) | 0.020 |

| ALT | 0.995 (0.991, 0.999) | 0.013 | 0.999 (0.990, 1.008) | 0.811 |

| AST | 0.993 (0.988, 0.997) | 0.002 | 0.995 (0.985, 1.004) | 0.247 |

| TBIL | 1.001 (0.998, 1.004) | 0.463 | ||

| PNI | 1.041 (1.004, 1.080) | 0.032 | 1.029 (0.985, 1.076) | 0.197 |

| Preoperative TACE number | 0.883 (0.787, 0.991) | 0.035 | 1.032 (0.882, 1.208) | 0.692 |

| Tumor differentiation (good) | 0.969 (0.636, 1.476) | 0.882 | ||

| MVI | 1.178 (0.824, 1.685) | 0.369 | ||

| Targeted therapy and immunotherapy (yes) | 3.485 (2.308, 5.261) | <0.001 | 3.283 (2.029, 5.312) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative TACE (yes) | 5.919 (3.850, 9.101) | <0.001 | 6.544 (4.021, 10.649) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Qin, C.; Lei, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W. Screening HCC Patients Who Can Benefit from the Sequential Treatment of Conversion Therapy and Radical Surgery and Constructing a Predictive Model. Cancers 2025, 17, 3928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243928

Liu L, Qin C, Lei K, Zhang H, Zhang W. Screening HCC Patients Who Can Benefit from the Sequential Treatment of Conversion Therapy and Radical Surgery and Constructing a Predictive Model. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243928

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lei, Chuan Qin, Kai Lei, Han Zhang, and Wenqian Zhang. 2025. "Screening HCC Patients Who Can Benefit from the Sequential Treatment of Conversion Therapy and Radical Surgery and Constructing a Predictive Model" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243928

APA StyleLiu, L., Qin, C., Lei, K., Zhang, H., & Zhang, W. (2025). Screening HCC Patients Who Can Benefit from the Sequential Treatment of Conversion Therapy and Radical Surgery and Constructing a Predictive Model. Cancers, 17(24), 3928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243928