Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies in Melanoma Diagnosis: A Narrative Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

2.2. Search Terms and Inclusion Criteria

- Original peer-reviewed research published between 1 January 2020 and 31 October 2025;

- Studies employing artificial intelligence or machine learning for the detection, classification, segmentation, or decision support of skin cancer or melanoma;

- Research integrating AI with advanced imaging modalities (e.g., dermoscopy, RCM, HFUS, OCT, or 3D total-body photography);

- Reports on prospective or real-world clinical validation, regulatory evaluation, or implementation of AI systems in healthcare workflows;

- English-language publications providing sufficient methodological detail to allow reproducibility and critical appraisal.

- Non-original works (e.g., editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces, or letters without primary data);

- Studies not related to melanoma or general dermatologic AI without clinical application;

- Purely algorithmic or technical research lacking medical or diagnostic validation;

- Duplicate analyzes of the same datasets without novel methodological or clinical insights.

2.3. Data Extraction and Categorization

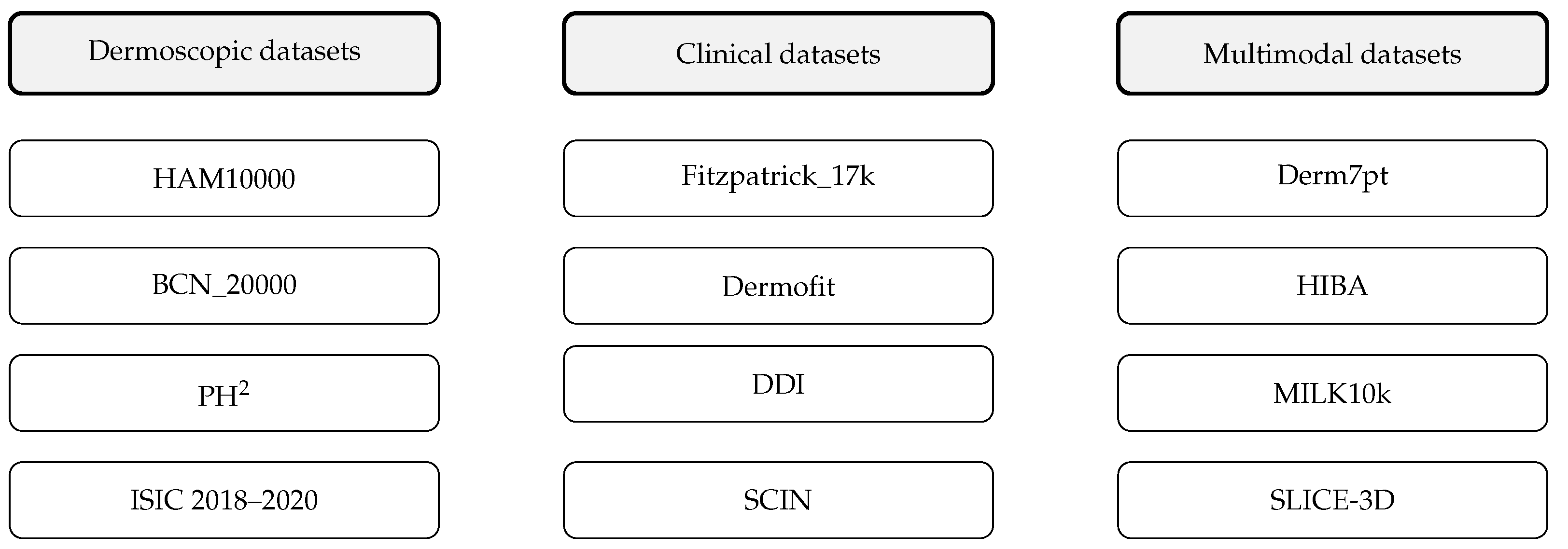

- Algorithmic Development: model architectures (CNN, Transformer, hybrid, or multimodal), training datasets, image modalities, and key performance metrics (AUC, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy);

- Data Resources: characteristics of public and institutional datasets (e.g., HAM10000, BCN_20000, Fitzpatrick_17k, PAD-UFES-20), including sample size, histopathologic verification, and representation of Fitzpatrick skin types;

- Clinical Validation: study design (retrospective, prospective, or real-world), study population, clinical setting (dermatology, teledermatology, or primary care), and diagnostic endpoints;

- Regulatory and Ethical Aspects: adherence to AI reporting standards (TRIPOD-AI, STARD-AI, CLAIM), regulatory classification (FDA, EU AI Act), explainability, data privacy, and bias mitigation.

2.4. Scope and Limitations

3. Review of AI Advancements and New Technologies

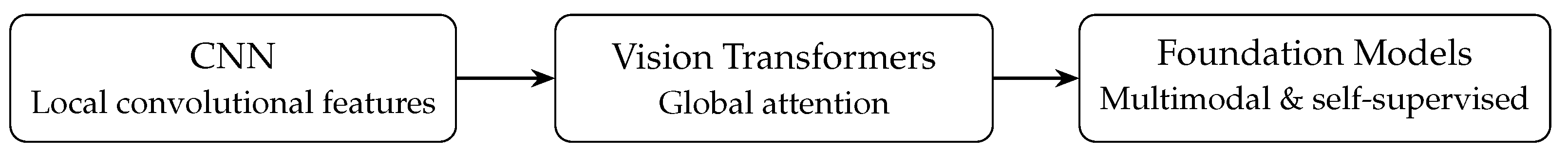

3.1. The Algorithmic Shift: From Convolution to Attention

3.1.1. Consolidation of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

3.1.2. The Rise of Vision Transformers (ViTs)

3.1.3. Performance Benchmarks: AI Versus Dermatologists

3.2. Data as the Foundation: Benchmark Datasets and Bias

3.2.1. Algorithmic Bias and Representation of Skin of Color

Clinical Impact of Bias and Regulatory Responses

3.3. Fusing AI with Advanced Imaging Modalities

3.3.1. Reflectance Confocal Microscopy (RCM)

3.3.2. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and High-Frequency Ultrasound (HFUS)

3.3.3. Three-Dimensional Total Body Photography (3D TBP)

3.3.4. Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI)

3.4. The New Frontier: Multimodal and Foundation Models

3.4.1. Radiomics and Multimodal Integration

3.4.2. Self-Supervised and Foundation Models

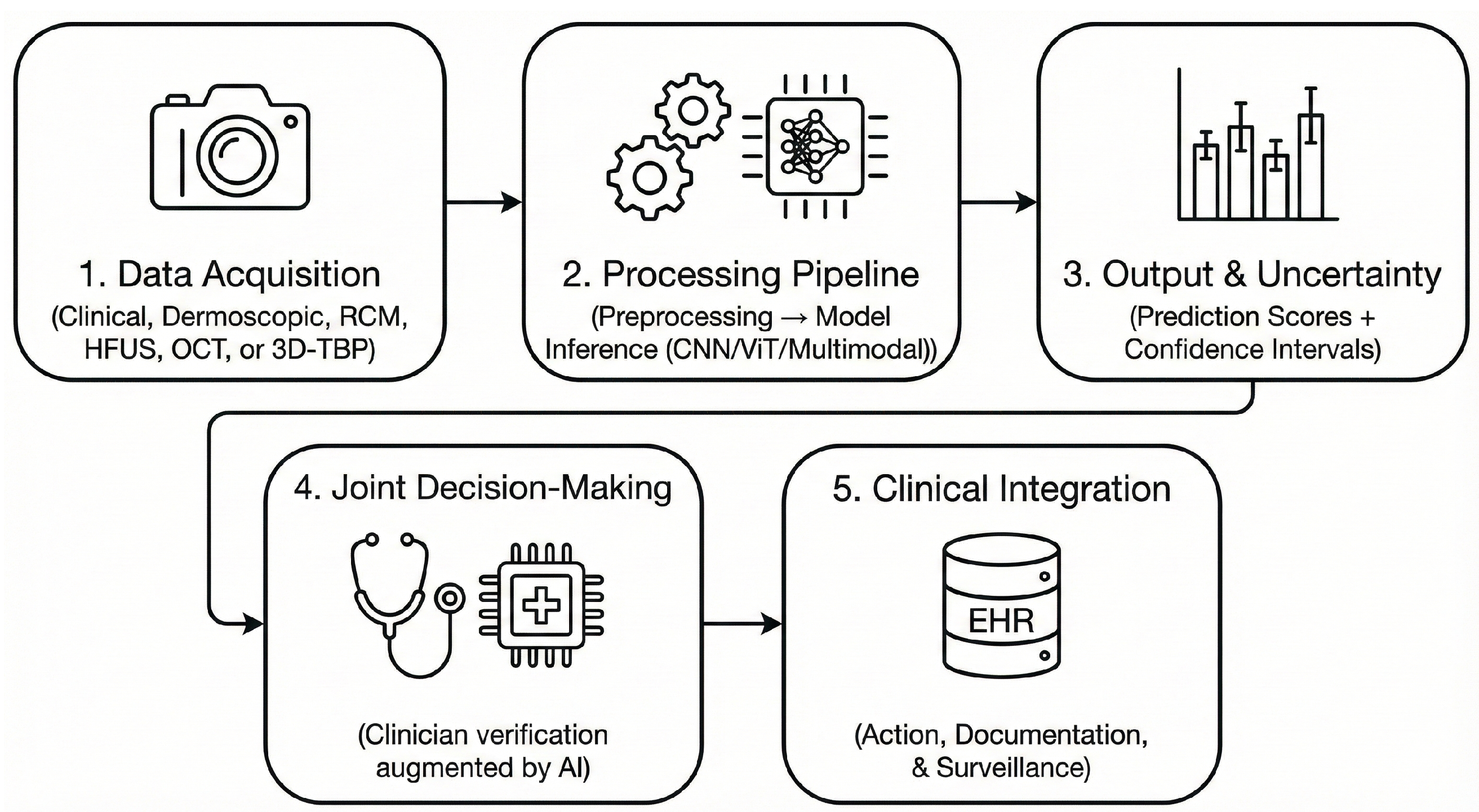

4. Clinical and Regulatory Translation

4.1. Integration of AI into Clinical Workflows

4.2. Validated Clinical Applications

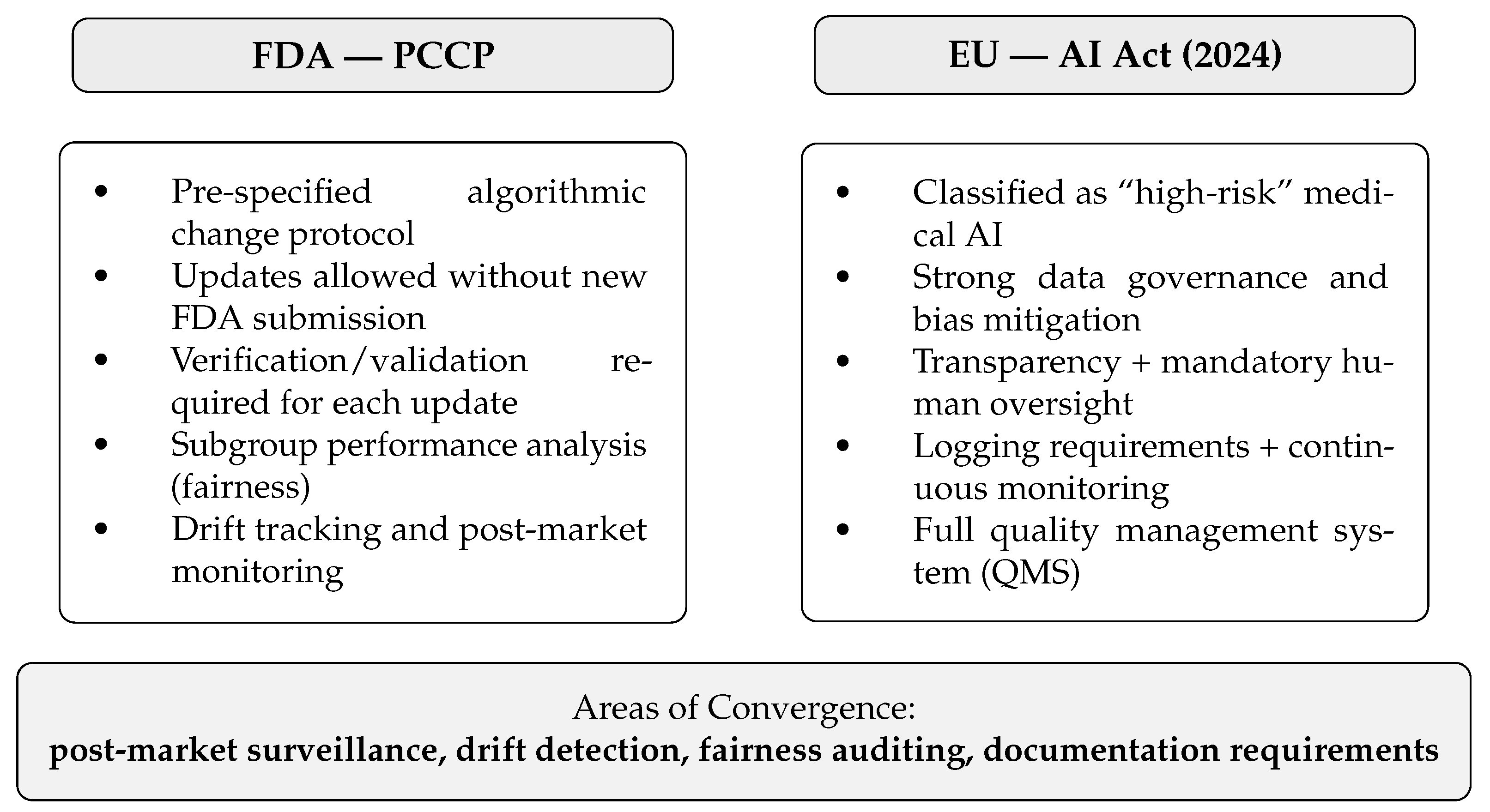

4.3. Regulatory Pathways: FDA and EU AI Act

Feasibility, Monitoring, and Unresolved Regulatory Gaps

5. Discussion: Trust, Translation, and the Path Forward

5.1. Validated Technologies and Prospective Evidence

5.2. Experimental Architectures and Early-Stage Research

5.3. Speculative and Emerging Future Directions

5.4. Algorithmic and Technical Maturation

5.5. Explainable AI and Ethical Transparency

5.6. Clinical Translation and Integration Challenges

5.7. Regulatory Evolution and Legal Liability

5.8. Privacy-Preserving and Federated Learning

5.9. Limitations and Future Directions

- Prospective and demographically diverse trials that assess the generalizability of the real world in healthcare systems and populations.

- Standardized reporting frameworks (e.g., TRIPOD-AI, CLAIM, STARD-AI) to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and comparability of results [67].

- Explainable and federated architectures that balance transparency with scalability and privacy preservation.

- Multimodal foundation models that integrate clinical, dermoscopic, histopathologic, and genomic data for the holistic characterization of melanoma [39].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| CLAIM | Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging |

| CLIP | Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DDI | Diverse Dermatology Images Dataset |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| ESS | Elastic Scattering Spectroscopy |

| EU AI Act | European Union Artificial Intelligence Act |

| FHIR | Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources |

| FM | Foundation Model |

| FST | Fitzpatrick Skin Type |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HFUS | High-Frequency Ultrasound |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| HSI | Hyperspectral Imaging |

| ISIC | International Skin Imaging Collaboration |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| PACS | Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| PCCP | Predetermined Change Control Plan (FDA) |

| QMS | Quality Management System |

| RCM | Reflectance Confocal Microscopy |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SaMD | Software as a Medical Device |

| Sn/Sp | Sensitivity/Specificity |

| SSL | Self-Supervised Learning |

| STARD-AI | Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy-AI |

| TBP | Total Body Photography |

| TRIPOD-AI | Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model-AI |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

References

- Wang, M.; Gao, X.; Zhang, L. Recent global patterns in skin cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 138, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlon, N.; Doddi, S.; Yousif, R.; Najib, S.; Sheikh, T.; Abuhelwa, Z.; Burmeister, C.; Hamouda, D.M. Melanoma Treatments and Mortality Rate Trends in the US, 1975 to 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2245269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, K.E.; Vihinen, H.; Heervä, E.; Nuotio, M.S.; Vihinen, P. The impact of prognostic factors and comorbidities on survival in older adults with stage I–III cutaneous melanoma in Southwest Finland: A register study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2024, 15, 101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okobi, O.E.; Abreo, E.; Sams, N.P.; Chukwuebuni, O.H.; Tweneboa Amoako, L.A.; Wiredu, B.; Uboh, E.E.; Ekechi, V.C.; Okafor, A.A. Trends in Melanoma Incidence, Prevalence, Stage at Diagnosis, and Survival: An Analysis of the United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) Database. Cureus 2024, 16, e70697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, M.; Harris, C.; Soenksen, L.; Lau, F.; Han, R.; Kim, A.; Koochek, A.; Badri, O. Evaluating Deep Neural Networks Trained on Clinical Images in Dermatology with the Fitzpatrick 17k Dataset. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.09957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.N.; Lee, M.S.; Kassamali, B.; Mita, C.; Nambudiri, V.E. Bias in, bias out: Underreporting and underrepresentation of diverse skin types in machine learning research for skin cancer detection—A scoping review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.T.; Xiong, M.; Pfau, J.; Keiser, M.J.; Wei, M.L. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: A Primer. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rinner, C.; Apalla, Z.; Argenziano, G.; Codella, N.; Halpern, A.; Janda, M.; Lallas, A.; Longo, C.; Malvehy, J.; et al. Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Abu Shugaer, M.; Khattab, K.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Varrassi, G. Histopathological Subtypes of Cutaneous Melanoma: Prognostic and Molecular Implications. Cureus 2025, emph17, e90670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Chan, W.; Shelmire, A.; Bandel, C.; Urbano, P.; Galambus, J.; Cockerell, C. Diagnostic Yield of Skin Biopsies Submitted to Rule out Melanoma. SKIN J. Cutan. Med. 2025, 9, 2594–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinlein, L.; Maron, R.C.; Hekler, A.; Haggenmüller, S.; Wies, C.; Utikal, J.S.; Meier, F.; Hobelsberger, S.; Gellrich, F.F.; Sergon, M.; et al. Prospective multicenter study using artificial intelligence to improve dermoscopic melanoma diagnosis in patient care. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, M.P.; Sepúlveda, J.; Hidalgo, L.; Peirano, D.; Morel, M.; Uribe, P.; Rotemberg, V.; Briones, J.; Mery, D.; Navarrete-Dechent, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of artificial intelligence versus clinicians for skin cancer diagnosis. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malciu, A.M.; Lupu, M.; Voiculescu, V.M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Approaches to Reflectance Confocal Microscopy Image Analysis in Dermatology. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; He, R.; Wei, T. The utility of high-frequency 18 MHz ultrasonography for preoperative evaluation of acral melanoma thickness in Chinese patients. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1185389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobelsberger, S.; Steininger, J.; Meier, F.E.; Beissert, S.; Gellrich, F.F. Three-Dimensional Total Body Photography, Digital Dermoscopy, and in vivo Reflectance Confocal Microscopy for Follow-Up Assessments of High-Risk Patients for Melanoma: A Prospective, Controlled Study. Dermatology 2024, 240, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Sommella, P.; Carratù, M.; O’Nils, M.; Lundgren, J. A Deep CNN Transformer Hybrid Model for Skin Lesion Classification of Dermoscopic Images Using Focal Loss. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.P.; Kadakia, K.T.; Gilbert, S. Learnings from the first AI-enabled skin cancer device for primary care authorized by FDA. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyakumar, J.P.; Jude, A.; Priya Henry, A.G.; Hemanth, J. Comparative Analysis of Melanoma Classification Using Deep Learning Techniques on Dermoscopy Images. Electronics 2022, 11, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermosilla, P.; Soto, R.; Vega, E.; Suazo, C.; Ponce, J. Skin Cancer Detection and Classification Using Neural Network Algorithms: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melarkode, N.; Srinivasan, K.; Qaisar, S.M.; Plawiak, P. AI-Powered Diagnosis of Skin Cancer: A Contemporary Review, Open Challenges and Future Research Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Ali, H.; Shah, Z. Identifying the role of vision transformer for skin cancer—A scoping review. Front. Artif. Intell. 2023, 6, 1202990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, G.; Chen, W.; Xu, A.; Hara, T.; Zhou, X.; Wu, D. DermViT: Diagnosis-Guided Vision Transformer for Robust and Efficient Skin Lesion Classification. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawani, H.T.; Senan, E.M.; Asiri, Y.; Abunadi, I.; Mashraqi, A.M.; Alshari, E.A. Enhanced early skin cancer detection through fusion of vision transformer and CNN features using hybrid attention of EViT-Dens169. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Su, J.; Chen, R.; Huang, R.; Dai, M.; Li, Y. SkinSwinViT: A Lightweight Transformer-Based Method for Multiclass Skin Lesion Classification with Enhanced Generalization Capabilities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; Ji, Z.; Cheng, L. Shifted windowing vision transformer-based skin cancer classification via transfer learning. Clinics 2025, 80, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.L.; Gong, T.T.; Song, X.J.; Chen, Q.; Bao, Q.; Yao, W.; Xie, M.M.; Li, C.; Grzegorzek, M.; Shi, Y.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Performance in Image-Based Cancer Identification: Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e53567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.; Rosic, N.; Stapelberg, M.; Hudson, J.; Coxon, P.; Furness, J.; Walsh, J.; Climstein, M. Performance of Commercial Dermatoscopic Systems That Incorporate Artificial Intelligence for the Identification of Melanoma in General Practice: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk Zararsız, G.; Yerlitaş Taştan, S.I.; Çelik Gürbulak, E.; Erakcaoğlu, A.; Yılmaz Işıkhan, S.; Demirbaş, A.; Ertaş, R.; Eroğlu, İ.; Korkmaz, S.; Elmas, Ö.F.; et al. Diagnosis melanoma with artificial intelligence systems: A meta-analysis study and systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 1912–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Akay, B.N.; Rosendahl, C.; Rotemberg, V.; Todorovska, V.; Weber, J.; Wolber, A.K.; Müller, C.; Kurtansky, N.; Halpern, A.; et al. MILK10k: A Hierarchical Multimodal Imaging-Learning Toolkit for Diagnosing Pigmented and Nonpigmented Skin Cancer and its Simulators. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, S.; Demircioglu, P.; Bogrekci, I. Advanced Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Comprehensive Dermatological Image Analysis and Diagnosis. Dermato 2024, 4, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.; Rotemberg, V.; Tschandl, P.; Celebi, M.E.; Dusza, S.; Gutman, D.; Helba, B.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Marchetti, M.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection 2018: A Challenge Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.03368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISIC Challenge—Challenge.isic-archive.com. Available online: https://challenge.isic-archive.com/landing/2019/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- The ISIC 2020 Challenge Dataset—Challenge2020.isic-archive.com. Available online: https://challenge2020.isic-archive.com/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Kurtansky, N.R.; D’Alessandro, B.M.; Gillis, M.C.; Betz-Stablein, B.; Cerminara, S.E.; Garcia, R.; Girundi, M.A.; Goessinger, E.V.; Gottfrois, P.; Guitera, P.; et al. The SLICE-3D dataset: 400,000 skin lesion image crops extracted from 3D TBP for skin cancer detection. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, C.; Combalia, M.; Podlipnik, S.; Codella, N.C.F.; Rotemberg, V.; Halpern, A.C.; Reiter, O.; Carrera, C.; Barreiro, A.; Helba, B.; et al. BCN20000: Dermoscopic Lesions in the Wild. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.Q.; Wang, Q.; Shi, Y.L.; Ren, W.W.; Cao, X.; Ren, T.T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Sun, Y.K.; Chen, X.W.; et al. A deep learning fusion network trained with clinical and high-frequency ultrasound images in the multi-classification of skin diseases in comparison with dermatologists: A prospective and multicenter study. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 67, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Xue, S.; Sun, F.; Sun, H.; Luo, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Guo, N.; Liu, L.; Zhao, T.; et al. Medical Multimodal Foundation Models in Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment: Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.02621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, A.G.; Lima, G.R.; Salomão, A.S.; Krohling, B.; Biral, I.P.; de Angelo, G.G.; Alves, F.C., Jr.; Esgario, J.G.; Simora, A.C.; Castro, P.B.; et al. PAD-UFES-20: A skin lesion dataset composed of patient data and clinical images collected from smartphones. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, T.; Ferreira, P.M.; Marques, J.S.; Marcal, A.R.S.; Rozeira, J. PH2—A dermoscopic image database for research and benchmarking. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; pp. 5437–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, J.; Daneshvar, S.; Argenziano, G.; Hamarneh, G. Seven-Point Checklist and Skin Lesion Classification Using Multitask Multimodal Neural Nets. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2019, 23, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermofit Image Library—The University of Edinburgh—Licensing.edinburgh-innovations.ed.ac.uk. Available online: https://licensing.edinburgh-innovations.ed.ac.uk/product/dermofit-image-library?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Daneshjou, R.; Vodrahalli, K.; Novoa, R.A.; Jenkins, M.; Liang, W.; Rotemberg, V.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Bailey, E.E.; Gevaert, O.; et al. Disparities in dermatology AI performance on a diverse, curated clinical image set. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.; Yasar, S.P.; Gencoglan, G.; Temelkuran, B. DERM12345: A Large, Multisource Dermatoscopic Skin Lesion Dataset with 40 Subclasses. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires—Skin Lesions Images (2019–2022). 2023. Available online: https://api.isic-archive.com/doi/hospital-italiano-de-buenos-aires-skin-lesions-images-2019-2022/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Ward, A.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Lakshminarasimhan, S.; Carrick, A.; Campana, B.; Hartford, J.; Sreenivasaiah, P.K.; Tiyasirisokchai, T.; Virmani, S.; et al. Creating an Empirical Dermatology Dataset through Crowdsourcing with Web Search Advertisements. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2446615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Mawgoud, R.; Posch, C. Visual explainability of 250 skin diseases viewed through the eyes of an AI-based, self-supervised vision transformer—A clinical perspective. JEADV Clin. Pract. 2024, 4, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, N.; Burke, T.; Courtney, J. Skin Type Diversity in Skin Lesion Datasets: A Review. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2024, 13, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellacani, G.; Farnetani, F.; Ciardo, S.; Chester, J.; Kaleci, S.; Mazzoni, L.; Bassoli, S.; Casari, A.; Pampena, R.; Mirra, M.; et al. Effect of Reflectance Confocal Microscopy for Suspect Lesions on Diagnostic Accuracy in Melanoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, N.N.; Boostani, M.; Farkas, K.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Lőrincz, K.; Posta, M.; Lihacova, I.; Lihachev, A.; Medvecz, M.; Holló, P.; et al. Optically Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Shows Superior Efficacy for Preoperative Estimation of Breslow Thickness in Comparison with Multispectral Imaging: A Single-Center Prospective Validation Study. Cancers 2023, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Mukundan, A.; Karmakar, R.; Avala, P.; Chang, W.Y.; Wang, H.C. Hyperspectral imaging for enhanced skin cancer classification using machine learning. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Karmakar, R.; Mukundan, A.; Chaudhari, S.; Hsiao, Y.P.; Hsieh, S.C.; Wang, H.C. Assessing the efficacy of the Spectrum-aided vision enhancer (SAVE) to detect acral lentiginous melanoma, melanoma in situ, nodular melanoma, and superficial spreading melanoma: Part II. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R.I.; Trepanowski, N.; Chang, M.S.; Tepedino, K.; Gianacas, C.; McNiff, J.M.; Fung, M.; Braghiroli, N.F.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Multicenter prospective blinded melanoma detection study with a handheld elastic scattering spectroscopy device. JAAD Int. 2024, 15, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangers, T.; Reeder, S.; van der Vet, S.; Jhingoer, S.; Mooyaart, A.; Siegel, D.M.; Nijsten, T.; Wakkee, M. Validation of a Market-Approved Artificial Intelligence Mobile Health App for Skin Cancer Screening: A Prospective Multicenter Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Dermatology 2022, 238, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, P.; Söderholm, M.; Pallon, J.; Taloyan, M.; Polesie, S.; Paoli, J.; Anderson, C.D.; Falk, M. Evaluation of an artificial intelligence-based decision support for the detection of cutaneous melanoma in primary care: A prospective real-life clinical trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2024, 191, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Luo, S.; Greer, P. Boosting Skin Cancer Classification: A Multi-Scale Attention and Ensemble Approach with Vision Transformers. Sensors 2025, 25, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavina-Bianchi, M.; Vitor, W.G.; Fornasiero de Paiva, V.; Okita, A.L.; Sousa, R.M.; Machado, B. Explainability agreement between dermatologists and five visual explanations techniques in deep neural networks for melanoma AI classification. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1241484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, K.; Kurz, A.; Haggenmüller, S.; Maron, R.C.; von Kalle, C.; Utikal, J.S.; Meier, F.; Hobelsberger, S.; Gellrich, F.F.; Sergon, M.; et al. Explainable artificial intelligence in skin cancer recognition: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 167, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kolfschooten, H.; van Oirschot, J. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (2024): Implications for healthcare. Health Policy 2024, 149, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebad, S.A.; Alhashmi, A.; Amara, M.; Miled, A.B.; Saqib, M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Software as a Medical Device (AI-SaMD): A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekadir, K.; Frangi, A.F.; Porras, A.R.; Glocker, B.; Cintas, C.; Langlotz, C.P.; Weicken, E.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Prior, F.; Collins, G.S.; et al. FUTURE-AI: International consensus guideline for trustworthy and deployable artificial intelligence in healthcare. BMJ 2025, 388, e081554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Roundup: December 3, 2024—Fda.gov. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-roundup-december-3-2024?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Hillis, J.M.; Visser, J.J.; Cliff, E.R.S.; van der Geest-Aspers, K.; Bizzo, B.C.; Dreyer, K.J.; Adams-Prassl, J.; Andriole, K.P. The lucent yet opaque challenge of regulating artificial intelligence in radiology. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieke, N.; Hancox, J.; Li, W.; Milletarì, F.; Roth, H.R.; Albarqouni, S.; Bakas, S.; Galtier, M.N.; Landman, B.A.; Maier-Hein, K.; et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaissis, G.A.; Makowski, M.R.; Rückert, D.; Braren, R.F. Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model/Architecture | Dataset(s) | Input Modality | Performance (AUC) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50/EfficientNet-B4 | HAM10000 [20]; ISIC 2018–2020 [33,34,35] | Dermoscopy | 0.94–0.96 [19,21] | Strong CNN baselines; limited global context [21] |

| DermViT/EViT-Dens169 | ISIC 2019–2024 [34,36] | Dermoscopy | 0.96–0.98 [24,25] | Superior global modeling; reduced parameter count [24,25] |

| Hybrid CNN–ViT (ConvNeXt, SkinSwinViT) | BCN_20000 [37]; MILK10k [31] | Dermoscopy + metadata | 0.97–0.98 [26,27] | Combines local CNN features with global self-attention [26,27] |

| Multimodal Fusion Models | MRA-MIDAS [38]; MILK10k [31] | Dermoscopy + clinical metadata | 0.95–0.98 [32,38] | Improved robustness and explainability through multimodal integration [32] |

| Foundation Models (PanDerm, DermINO) | Millions of unlabeled images + fine-tuning datasets [32,39] | Clinical + dermoscopy | 0.97–0.99 [28,29,30] | Highest generalizability; strong external validation [28,29] |

| Dataset | Size (Images) | Image Type | Biopsy Confirmation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section A. Core Benchmark Datasets (commonly used 2020–2025) | ||||

| HAM10000 [20] | 10,015 | Dermoscopic | >50% | Class imbalance; light-skin bias |

| BCN_20000 [37] | 18,946 | Dermoscopic | 100% malignancies | Single-centre; limited FST diversity |

| Fitzpatrick_17k [6] | 16,577 | Clinical photos | Mixed | Skewed FST distribution; unbalanced |

| PAD-UFES-20 [40] | 2298 | Smartphone images | 100% cancers | Small size; variable quality |

| PH2 [41] | 200 | Dermoscopic | 20% | Very small; outdated |

| Section B. Supplementary and Emerging Datasets (diversity, multimodality, 3D-TBP, metadata) | ||||

| Derm7pt [42] | 2000+ | Dermoscopic + Clinical | Mixed | Limited diversity |

| Dermofit [43] | 1300 | Clinical | – | Restricted access |

| DDI [44] | 656 | Clinical photos | – | Small size; excellent FST diversity |

| ISIC 2018–2020 [33,34,35] | 157,000+ | Dermoscopic | Mixed | Heterogeneous annotation |

| SLICE-3D (ISIC 2024) [36] | 400,000+ | 3D-TBP crops | Mixed | New modality; limited validation |

| Derm12345 [45] | 12,345 | Dermatoscopic | – | Limited accessibility |

| MILK10k [31] | 5240 + 479 test | Multimodal (Clinical + Dermoscopy + Metadata) | – | Benchmark for multimodal models |

| HIBA Skin Lesions [46] | 1616 | Clinical + Dermoscopy | Mixed | Single-centre origin |

| SCIN [47] | 10,000+ | Clinical (skin, nail, hair) | – | Not melanoma-focused |

| SD-128/SD-260 [48] | 6584 | Clinical photos | – | Broad-spectrum dermatology |

| Modality | Maturity Level | Clinical Evidence Strength | Clinical Use-Cases/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dermoscopy | High | Strong evidence from large retrospective datasets; supported by multiple prospective clinician–AI comparison trials. | Operator-dependent; image quality and device variability can affect performance. |

| RCM | Moderate | Several prospective trials showing high diagnostic accuracy and biopsy reduction. | Near-histologic resolution; limited availability, high cost, time-consuming acquisition. |

| OCT/HFUS | Moderate | Growing early-stage clinical validation; correlation with Breslow thickness frequently reported. | Useful for depth estimation and preoperative planning; limited resolution for subtle morphological changes. |

| 3D TBP | Emerging | Limited but increasing prospective evidence; strong performance in longitudinal monitoring. | Best for high-risk patients; dependent on standardized image acquisition; emerging AI support for change detection. |

| Device/Trial ID | Technology | Clinical Context/Regulatory Outcome | Sn/Sp for Melanoma |

|---|---|---|---|

| DermaSensor (NCT05126173) | Elastic scattering spectroscopy (ESS) with ML-based lesion risk classification. | Validated in the multicenter DERM-ASSESS III trial in primary care; authorized by the U.S. FDA under the De Novo pathway in 2024. | 95.5%/ 20.7–32.5% |

| Dermalyzer (NCT05172232) | CNN-based decision support tool for suspicious lesion triage. | Evaluated in general practice; 2023 prospective study reported high diagnostic accuracy, supporting its use in non-specialist settings. | 95%/86% |

| MoleMap AI (NCT04040114) | Deep learning classifier for melanoma detection and triage. | Assessed in dermatology specialist clinics; demonstrated substantial agreement with expert dermatologists and strong triage performance. | – |

| SkinVision | Smartphone-based CNN for self-screening and risk stratification. | CE-marked class IIa device used in teledermatology workflows across the EU; validated for high-risk lesion detection. | 92.1%/80.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Górecki, S.; Tatka, A.; Brusey, J. Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies in Melanoma Diagnosis: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243896

Górecki S, Tatka A, Brusey J. Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies in Melanoma Diagnosis: A Narrative Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243896

Chicago/Turabian StyleGórecki, Sebastian, Aleksandra Tatka, and James Brusey. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies in Melanoma Diagnosis: A Narrative Review" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243896

APA StyleGórecki, S., Tatka, A., & Brusey, J. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies in Melanoma Diagnosis: A Narrative Review. Cancers, 17(24), 3896. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243896