Non-Contrast MR T2-Weighted Imaging Is as Accurate as Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted Imaging in the Detection of Meningioma Growth

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

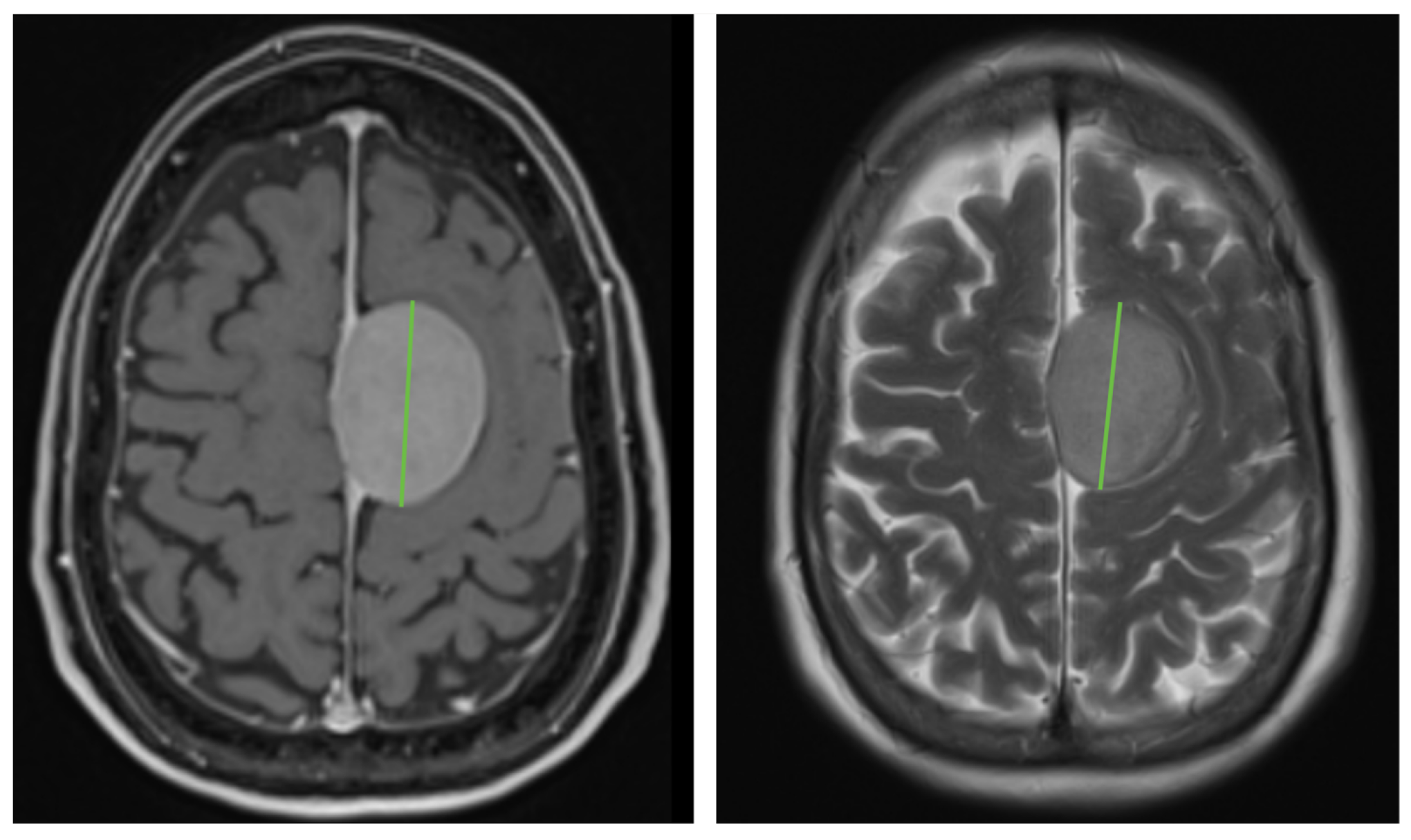

2.2. Imaging Protocol

2.3. Data Interpretation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CE-T1WI | Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted Images |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| GBCA | Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents |

| Gd3+ | Gadolinium |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| T1WI | T1-Weighted Images |

| T2WI | T2-Weighted Images |

References

- Buerki, R.A.; Horbinski, C.M.; Kruser, T.; Horowitz, P.M.; James, C.D.; Lukas, R.V. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018, 14, 2161–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, Z.; Whiteley, W.N.; Longstreth, W.T., Jr.; Weber, F.; Lee, Y.C.; Tsushima, Y.; Alphs, H.; Ladd, S.C.; Warlow, C.; Wardlaw, J.M.; et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj 2009, 339, b3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasu, S.; Nakasu, Y. Natural History of Meningiomas: Review with Meta-analyses. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2020, 60, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oya, S.; Kim, S.H.; Sade, B.; Lee, J.H. The natural history of intracranial meningiomas. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 114, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, R.; Ryan, G.; Benner, C.; Pollock, J. Non-operative meningiomas: Long-term follow-up of 136 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Database, R. Intracranieel Meningeoom—Beeldvorming-Richtlijn. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/intracranieel_meningeoom/diagnostiek/beeldvorming.html (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Chidambaram, S.; Pannullo, S.C.; Roytman, M.; Pisapia, D.J.; Liechty, B.; Magge, R.S.; Ramakrishna, R.; Stieg, P.E.; Schwartz, T.H.; Ivanidze, J. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging perfusion characteristics in meningiomas treated with resection and adjuvant radiosurgery. Neurosurg. Focus. 2019, 46, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Y.; Bi, W.L.; Griffith, B.; Kaufmann, T.J.; la Fougère, C.; Schmidt, N.O.; Tonn, J.C.; Vogelbaum, M.A.; Wen, P.Y.; Aldape, K.; et al. Imaging and diagnostic advances for intracranial meningiomas. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21, i44–i61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.Q.; Iv, M.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Hayden Gephart, M. Noncontrast T2-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequences for Long-Term Monitoring of Asymptomatic Convexity Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2020, 135, e100–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raban, D.; Patel, S.H.; Honce, J.M.; Rubinstein, D.; DeWitt, P.E.; Timpone, V.M. Intracranial meningioma surveillance using volumetrics from T2-weighted MRI. J. Neuroimaging 2022, 32, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahatli, F.K.; Donmez, F.Y.; Kesim, C.; Haberal, K.M.; Turnaoglu, H.; Agildere, A.M. Can unenhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging be used in routine follow up of meningiomas to avoid gadolinium deposition in brain? Clin. Imaging 2019, 53, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boto, J.; Guatta, R.; Fitsiori, A.; Hofmeister, J.; Meling, T.R.; Vargas, M.I. Is Contrast Medium Really Needed for Follow-up MRI of Untreated Intracranial Meningiomas? AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, M.A.; Kunst, H.P.M.; Rovers, M.M.; Steens, S.C.A. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution T2-weighted MRI vs. contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI to screen for cerebellopontine angle lesions in symptomatic patients. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2018, 43, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukamp, K.R.; Shakirin, G.; Baeßler, B.; Thiele, F.; Zopfs, D.; Große Hokamp, N.; Timmer, M.; Kabbasch, C.; Perkuhn, M.; Borggrefe, J. Accuracy of Radiomics-Based Feature Analysis on Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Images for Noninvasive Meningioma Grading. World Neurosurg. 2019, 132, e366–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, T.; Takahashi, W.; Haga, A.; Takahashi, S.; Kiryu, S.; Nawa, K.; Ohta, T.; Ozaki, S.; Nozawa, Y.; Tanaka, S.; et al. Prediction of malignant glioma grades using contrast-enhanced T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images based on a radiomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.C.; Carr, C.M.; Eckel, L.J.; Kotsenas, A.L.; Hunt, C.H.; Carlson, M.L.; Lane, J.I. Utility of Noncontrast Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Detection of Recurrent Vestibular Schwannoma. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzini, F.B.; Sarno, A.; Galazzo, I.B.; Fiorino, F.; Aragno, A.M.R.; Ciceri, E.; Ghimenton, C.; Mansueto, G. Usefulness of High Resolution T2-Weighted Images in the Evaluation and Surveillance of Vestibular Schwannomas? Is Gadolinium Needed? Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, e103–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, J.; Olkowska, E.; Ratajczyk, W.; Wolska, L. Gadolinium as a new emerging contaminant of aquatic environments. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Port, M.; Idée, J.M.; Medina, C.; Robic, C.; Sabatou, M.; Corot, C. Efficiency, thermodynamic and kinetic stability of marketed gadolinium chelates and their possible clinical consequences: A critical review. Biometals 2008, 21, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Ishii, K.; Kawaguchi, H.; Kitajima, K.; Takenaka, D. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: Relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology 2014, 270, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semelka, R.C.; Ramalho, M. Gadolinium Deposition Disease: Current State of Knowledge and Expert Opinion. Investig. Radiol. 2023, 58, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA Identifies No Harmful Effects to Date with Brain Retention of Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents for MRIs; Review to Continue. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-evaluating-risk-brain-deposits-repeated-use-gadolinium-based (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Gulani, V.; Calamante, F.; Shellock, F.G.; Kanal, E.; Reeder, S.B. Gadolinium deposition in the brain: Summary of evidence and recommendations. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, L.A.; DeWire-Schottmiller, M.D.; Fouladi, M.; DeBlank, P.; Leach, J.L. Tumor Response Assessment in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma: Comparison of Semiautomated Volumetric, Semiautomated Linear, and Manual Linear Tumor Measurement Strategies. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, K.E.; Patronas, N.; Aikin, A.A.; Albert, P.S.; Balis, F.M. Comparison of one-, two-, and three-dimensional measurements of childhood brain tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 1401–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arco, F.; O’Hare, P.; Dashti, F.; Lassaletta, A.; Loka, T.; Tabori, U.; Talenti, G.; Thust, S.; Messalli, G.; Hales, P.; et al. Volumetric assessment of tumor size changes in pediatric low-grade gliomas: Feasibility and comparison with linear measurements. Neuroradiology 2018, 60, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, G.T.; Armitage, P.A.; Batty, R.; Griffiths, P.D.; Lee, V.; McMullan, J.; Connolly, D.J. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: Is MRI surveillance improved by region of interest volumetry? Pediatr. Radiol. 2015, 45, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Zhou, Z.; Tisnado, J.; Haque, S.; Peck, K.K.; Young, R.J.; Tsiouris, A.J.; Thakur, S.B.; Souweidane, M.M. A novel magnetic resonance imaging segmentation technique for determining diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma tumor volume. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2016, 18, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behbahani, M.; Skeie, G.O.; Eide, G.E.; Hausken, A.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Skeie, B.S. A prospective study of the natural history of incidental meningioma-Hold your horses! Neurooncol Pract. 2019, 6, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, N.; Rabo, C.S.; Okita, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Kagawa, N.; Fujimoto, Y.; Morii, E.; Kishima, H.; Maruno, M.; Kato, A.; et al. Slower growth of skull base meningiomas compared with non-skull base meningiomas based on volumetric and biological studies. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 116, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadid, K.D.; Feychting, M.; Höijer, J.; Hylin, S.; Kihlström, L.; Mathiesen, T. Long-term follow-up of incidentally discovered meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 2015, 157, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasu, S.; Onishi, T.; Kitahara, S.; Oowaki, H.; Matsumura, K.I. CT Hounsfield Unit Is a Good Predictor of Growth in Meningiomas. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2019, 59, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | T2WI | CE-T1WI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial tumor diameter (mm (SD; range)) | 20.1 (11.8; 5.2–63.5) | 20.8 (12.1; 6.3–72.1) | <0.001 |

| Tumor growth (mm (mean (SD; range)) | 0.99 (2.96; −7.1–17.2) | 0.53 (2.48; −11.6–10.4) | 0.057 |

| Average tumor growth in millimeters (mm/year (SD; range)) | 0.69 (2.2; −3.7–15.7) | 0.26 (1.8; −10.6–6.1) | 0.076 |

| Average tumor growth in percentage (%/year (SD; range)) | 4.1 (12.7; −13.3–102.4) | 1.8 (7.1; −17.9–21.7 | 0.038 |

| Proportional tumor growth (n (%)) | |||

| None | 34 (34.3) | 37 (37.4) | 0.460 |

| <10% | 49 (49.5) | 52 (52.5) | |

| ≥10% | 16 (16.2) | 10 (10.1) |

| Any Yearly Tumor Growth | Yearly Tumor Growth ≥ 10% | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 79.0% | 80.0% |

| Specificity | 56.8% | 89.9% |

| PPV | 75.4% | 47.1% |

| NPV | 61.8% | 97.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dijkstra, B.M.; Padmos, G.A.; Broen, M.P.G.; Eekers, D.B.P.; Anten, M.H.M.E.; Postma, A.A. Non-Contrast MR T2-Weighted Imaging Is as Accurate as Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted Imaging in the Detection of Meningioma Growth. Cancers 2025, 17, 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233800

Dijkstra BM, Padmos GA, Broen MPG, Eekers DBP, Anten MHME, Postma AA. Non-Contrast MR T2-Weighted Imaging Is as Accurate as Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted Imaging in the Detection of Meningioma Growth. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233800

Chicago/Turabian StyleDijkstra, Bianca M., Guillaume A. Padmos, Martijn P. G. Broen, Daniëlle B. P. Eekers, Monique H. M. E. Anten, and Alida A. Postma. 2025. "Non-Contrast MR T2-Weighted Imaging Is as Accurate as Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted Imaging in the Detection of Meningioma Growth" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233800

APA StyleDijkstra, B. M., Padmos, G. A., Broen, M. P. G., Eekers, D. B. P., Anten, M. H. M. E., & Postma, A. A. (2025). Non-Contrast MR T2-Weighted Imaging Is as Accurate as Contrast-Enhanced T1-Weighted Imaging in the Detection of Meningioma Growth. Cancers, 17(23), 3800. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233800