Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Histotype-Driven Literature Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

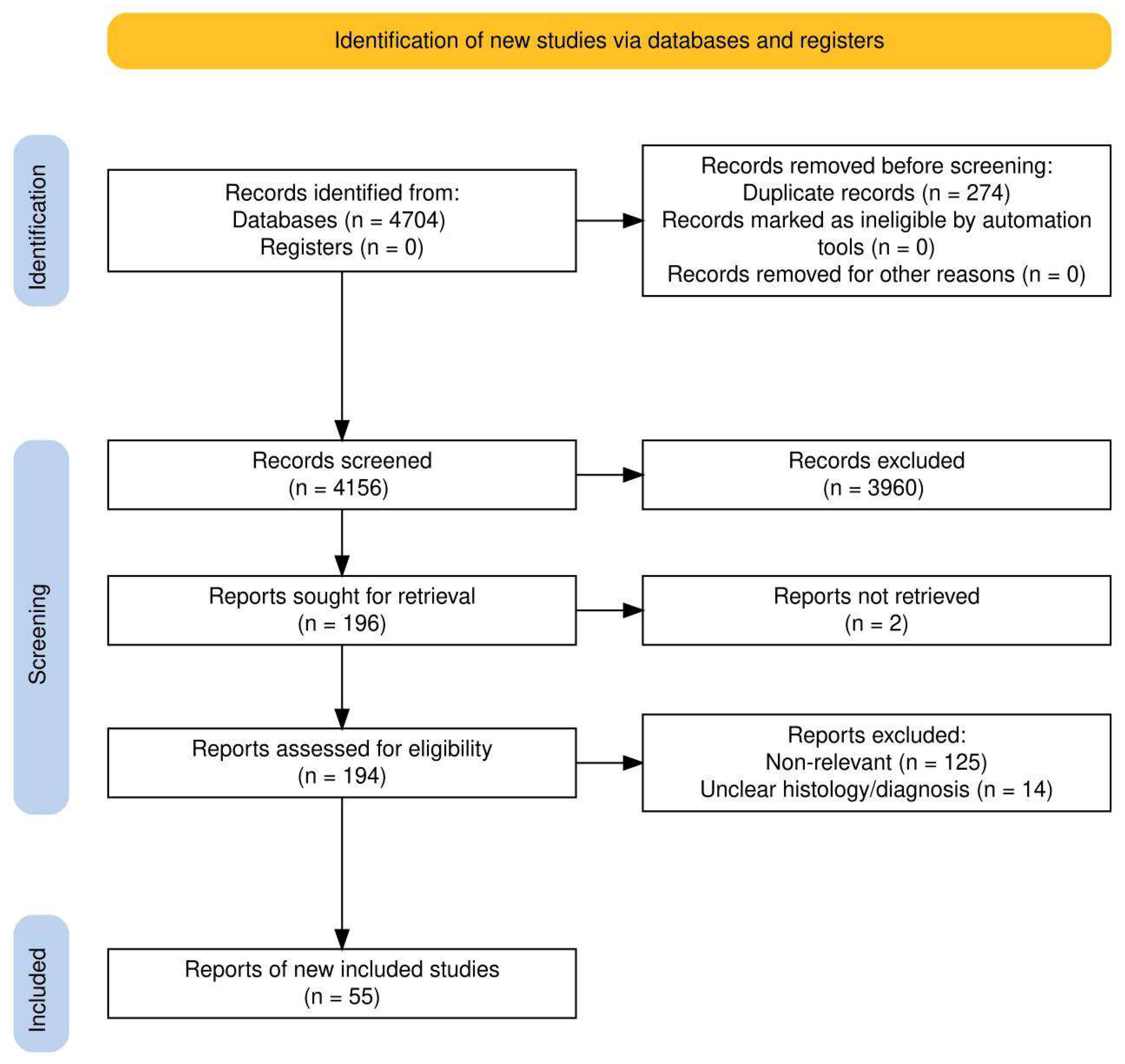

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Work-Up

3.2. Principles of Treatment for LSTs

3.3. Clinicopathological Update on the Most Common LST Histologies

3.4. Inverted Papilloma

3.5. Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Stage I

- Confined to LS fossa;

- Stage II

- Invasion of globe, nasolacrimal duct, canaliculi, caruncle, or conjunctiva;

- Stage III

- Invasion of nasal cavity/paranasal sinuses, bone, or skin;

- Stage IV

- Extension to orbital apex, meninges, brain, N+, or M+.

3.6. Lymphoproliferative Tumors

3.7. Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma (MEC) and Other Salivary Gland-Type Carcinomas of the Lacrimal Drainage System

3.8. Melanoma Involving the Lacrimal Drainage System

3.9. Metastatic Tumors to the Lacrimal Sac

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Munjal, M.; Munjal, S.; Vohra, H.; Prabhakar, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Soni, A.; Gupta, S.; Agarwal, M. Anatomy of the lacrimal apparatus from a rhinologist’s perspective: A review. Int. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 7, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, F. The human nasolacrimal ducts. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2003, 170, 1–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Locatello, L.G.; Redolfi De Zan, E.; Caiazza, N.; Tarantini, A.; Lanzetta, P.; Miani, C. A critical update on endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2024, 44, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Locatello, L.G.; Redolfi De Zan, E.; Tarantini, A.; Lanzetta, P.; Miani, C. External dacryocystorhinostomy: A critical overview of the current evidence. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 35, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Ali, M.J. Primary Malignant Epithelial Tumors of the Lacrimal Drainage System: A Major Review. Orbit 2020, 40, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, T.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Goldman-Levy, G.; Kivelä, T.T.; Coupland, S.E.; White, V.A.; Mudhar, H.S.; Eberhart, C.G.; Verdijk, R.M.; Heegaard, S.; et al. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Eye and Orbit. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2023, 9, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krishna, Y.; Coupland, S.E. Lacrimal sac tumors: A review. Asia. Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 6, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.J. Dacryocystectomy: Goals, indications, techniques and complications. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 30, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campobasso, G.; Ragno, M.S.; Monda, A.; Ciccarone, S.; Maselli Del Giudice, A.; Barbara, F.; Gravante, G.; Lucchinelli, P.; Arosio, A.D.; Volpi, L.; et al. Exclusive or combined endoscopic approach to tumours of the lower lacrimal pathway: Review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2024, 44 (Suppl. S1), S67–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell. Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corporation for Digital Scholarship. Zotero (7.0.11). 2025. [Software]. Available online: https://www.zotero.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Kadir, S.M.U.; Rashid, R.; Sultana, S.; Nuruddin, M.; Nessa, M.S.; Mitra, M.R.; Haider, G. Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Case Series. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2022, 8, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, H.-S.; Shi, J.-T.; Wei, W.-B. Clinical Analysis of Primary Malignant Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Case Series Study With a Comparison to the Previously Published Literature. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2023, 34, e115–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakasaki, T.; Yasumatsu, R.; Tanabe, M.; Yoshikawa, H.; Jiromaru, R.; Hashimoto, K.; Matsuo, M.; Fujimura, A.; Nakagawa, T. Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Single-institution Experience, Including New Insights. Vivo 2023, 37, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vibert, R.; Cyrta, J.; Girard, E.; Vacher, S.; Dupain, C.; Antonio, S.; Wong, J.; Baulande, S.; De Sousa, J.M.F.; Vincent--Salomon, A.; et al. Molecular characterisation of tumours of the lacrimal apparatus. Histopathology 2023, 83, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.-C.; Tsai, C.-C. Delayed Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis of Lacrimal Sac Tumors in Patients Presenting with Epiphora: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, M.; Juniat, V.; Ezra, D.G.; Verity, D.H.; Uddin, J.; Timlin, H. Blood-stained tears-a red flag for malignancy? Eye 2023, 37, 1711–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kuo, C.Y.; Tsai, C.C.; Kao, S.C.; Hsu, W.M.; Jui-Ling Liu, C. Comparison of Clinical Features and Treatment Outcome in Benign and Malignant Lacrimal Sac Tumors. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3545839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tong, J.Y.; Juniat, V.; Selva, D. Radiological Features of Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Involving the Lacrimal Sac. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 37, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldaya, R.W.; Deolankar, R.; Orlowski, H.L.; Miller-Thomas, M.M.; Wippold, F.J., II; Parsons, M.S. Neuroimaging of adult lacrimal drainage system. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2021, 50, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Ku, W.N.; Kung, W.H.; Huang, Y.; Chiang, C.C.; Lin, H.J.; Tsai, Y.Y. Navigation-assisted endoscopic surgery of lacrimal sac tumor. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 10, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, F.; Ali, M.J.; Xiao, C. Primary Lacrimal Sac Tumors with Extension into Vicinity: Outcomes with Endoscopy-Assisted Modified Weber-Ferguson’s Approach. Curr. Eye Res. 2024, 49, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.; Daniel, C.; Faulkner, J.; Uddin, J.; Arora, A.; Jeannon, J.P. Robotic assisted orbital surgery for resection of advanced periocular tumours—A case series report on the feasibility, safety and outcome. Eye 2024, 38, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Swendseid BGodovchik JVimawala, S.; Garrett, S.; Topf, M.; Luginbuhl, A.; Cognetti, D.; Curry, J. The Role of Cervical and Parotid Lymph Nodes in Surgical Management of Malignant Tumors of the Lacrimal Sac. J. Neurol. Surg. B 2020, 81, A201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.Y.; Wang, Z.S.; Jia, J.X.; Chen, X.Q.; Lyu, F.; Liu, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, S.W.; Ma, M.W.; Gao, X.S. Enhancing precision in lacrimal sac tumor management through integration of multimodal imaging and intensity modulated proton therapy. Med. Dosim. 2025, 50, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Ma, N.; Zhang, S.; Ning, X.; Guo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Li, Y. Iodine-125 interstitial brachytherapy for malignant lacrimal sac tumours: An innovative technique. Eye 2021, 35, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldfarb, J.; Fan, J.; de Sousa, L.G.; Akhave, N.; Myers, J.; Goepfert, R.; Manisundaram, K.; Zhao, J.; Frank, S.J.; Moreno, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Alone or Combined with EGFR-Directed Targeted Therapy or Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy for Locally Advanced Lacrimal Sac and Nasolacrimal Duct Carcinomas. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2024, 39, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, M.H.; Yi, W.D.; Shen, L.; Zhou, L.; Lu, J.X. Transcatheter arterial infusion chemotherapy and embolization for primary lacrimal sac squamous cell carcinoma: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 7467–7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Panda, B.B.; Viswanath, S.; Baisakh, M.; Rauta, S. Solitary fibrous tumour of lacrimal sac masquerading as lacrimal sac mucocele: A diagnostic and surgical dilemma. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e250015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samaddar, A.; Kakkar, A.; Sakthivel, P.; Kumar, R.; Jain, D.; Mathur, S.R.; Iyer, V.K. Cytological diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumour of the lacrimal sac: Role of immunocytochemistry for STAT6. Cytopathology 2021, 32, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Neiweem, A.; Davis, K.; Prendes, M.; Chundury, R.; Illing, E. Epithelial-Myoepithelial Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Sac and Literature Review of the Lacrimal System. Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 11, 2152656720920600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almutairi, F.; Alsamnan, M.; Maktabi, A.; Elkhamary, S.; Alkatan, H.M.; AlOtaibi, H. Recurrent Oncocytoma of the Lacrimal Sac. Case Rep. Pathol. 2022, 2022, 2955030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gupta, A.; Abhaypal, K.; Chatterjee, D.; Kaur, M.; Singh, M. Primary anaplastic extramedullary plasmacytoma in the lacrimal sac. Digit J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 30, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, S.V.; Mishra, N.; Kumar, V.; Sati, A.; Kumar, N.V.; Bandopadhyay, S. Angiofibroma of the lacrimal sac: A rare case report. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 2, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.V.; Siddens, J.D. Rare transitional cell carcinoma of the lacrimal sac. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2020, 20, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dash, S.; Mohapatra, M.M.; Sarangi, S.; Bidasaria, A. Hemangiopericytoma of the lacrimal sac: A rare case report and review of literature. Indian J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2024, 4, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seethapathi, G.; Jeganathan, S. Case report of an isolated lacrimal sac rhabdomyosarcoma. Indian J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2023, 3, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Chandran, V.A.; KrishnaKumar, S. Primary apocrine adenocarcinoma of the lacrimal sac: An extremely rare variant of lacrimal sac neoplasm. Orbit 2022, 41, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Hosono, M.; Kawabata, K.; Kawamura, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Kanagaki, M. Inverted papilloma originating from the lacrimal sac and the nasolacrimal duct with marked FDG accumulation. Radiol. Case Rep. 2021, 16, 3577–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheang, Y.F.A.; Loke, D. Inverted Papilloma of the Lacrimal Sac and Nasolacrimal Duct: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus 2020, 12, e6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramberg, I.; Toft, P.B.; Heegaard, S. Carcinomas of the lacrimal drainage system. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 65, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.M.F.; Brega, D.R.; Gollner, A.M.; Gonçalves, A.C.P. Chronic unilateral tearing as a sign of lacrimal sac squamous cell carcinoma. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2021, 84, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Poghosyan, A.; Gharakeshishyan, A.; Misakyan, M.; Minasyan, D.; Khachatryan, P.; Mashinyan, K.; Hovhannisyan, S.; Kharazyan, A. Lacrimal sac squamous cell carcinoma: From resection to prosthetic rehabilitation. A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grachev, N.; Rabaev, G.; Avdalyan, A.; Znamenskiy, I.; Mosin, D.; Ustyuzhanin, D.; Rabaev, G.; Lužbeták, M. HER2-Positive Lacrimal Sac Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a 57-Year-Old Man. Case Rep. Oncol. 2024, 17, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hao, L.; Luo, B.; Long, T.; Hu, S. PET/CT Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus-Positive Lacrimal Sac Carcinoma in Unknown Primary Cervical Nodal Metastasis. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2025, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, R.; Haigh, O.; Racy, E.; Bordonne, C.; Barreau, E.; Rousseau, A.; Labetoulle, M. Human papilloma virus (HPV) presence in primary tumors of the lacrimal sac: A case series and review of the literature. Orbit 2025, 44, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiad, A.A.; Bakalian, S.; Dahoud, J.; Arthurs, B.; El-Hadad, C. Cemiplimab in combination with induction chemotherapy for the treatment of locally advanced lacrimal sac squamous cell carcinoma. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 60, e495–e498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pośpiech, J.; Hypnar, J.; Horosin, G.; Możdżeń, K.; Murawska, A.; Przeklasa, M.; Konior, M.; Tomik, J. Rare Case of Non-Keratinizing Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the Lacrimal Sac Treated with Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, C.Y.; Saravanamuthu, K.; Kasim, W.M.W.M. From Seed to Spread: Lacrimal Sac Squamous Cell Carcinoma Blossoming Into Orbital Chaos. Cureus. 2024, 16, e63452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, S.; Ali, M.J. Lymphoproliferative tumors involving the lacrimal drainage system: A major review. Orbit 2020, 39, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.-X.; Yue, H.; Zhang, R.; Yuan, Y.-F.; Bi, Y.-W.; Qian, J. Lacrimal sac lymphoma: A case series and literature review. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 15, 1586–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, F.; Tao, H.; Zhou, X.B.; Wang, F.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.H.; Zhang, H.Y. Primary lacrimal sac lymphoma: A case-based retrospective study in a Chinese population. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 16, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ucgul, A.Y.; Tarlan, B.; Gocun, P.U.; Konuk, O. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the lacrimal drainage system in two pediatric patients. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 30, NP18–NP23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadhar, B.; Slupek, D.; Steehler, A.; Denne, C.; Steehler, K. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the lacrimal sac with involvement of maxillary sinus: A case report and review of literature. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 2024, rjae453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjamilah, M.N.; Zamli, A.H.; Tai, E.; Shatriah, I. Bilateral Primary Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma of the Lacrimal Sac: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e29114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gervasio, K.A.; Zhang, P.J.L.; Penne, R.B.; Stefanyszyn, M.A.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Puthiyaveettil, R.; Milman, T. Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Sac: Clinical-Pathologic Analysis, Including Molecular Genetics. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2020, 6, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, H.; Cai, R.; Zhai, C.; Song, W.; Sun, J.; Bi, Y. Primary Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Apparatus. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 239, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Q.; Liu, D.; Yu, H.; Zhong, Y.; Zhou, Y. Successful management of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal sac with apatinib combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A case report. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 8334–8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imrani, K.; Oubaddi, T.; Jerguigue, H.; Latib, R.; Omor, Y. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal sac: A case report. Int. J. Case Rep. Images 2021, 12, 101273Z01KI2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Patidar, N.R.A.; Arora Agrawal, P.; Tekam, D.K. Poorly differentiated sebaceous carcinoma of the lacrimal sac in a young adult: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2024, 12, 2050313X241271787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takizawa, D.; Ohnishi, K.; Hiratsuka, K.; Matsuoka, R.; Baba, K.; Nakamura, M.; Iizumi, T.; Suzuki, K.; Mizumoto, M.; Sakurai, H. Primary adenocarcinoma of the lacrimal sac with 5-year recurrence-free survival after radiation therapy alone: A case report. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2025, 14, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abramson, D.H.; Fallon, J.; Biran, N.; Francis, J.H.; Jaben, K.; Oh, W.K. Lacrimal sac adenocarcinoma managed with androgen deprivation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2020, 19, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheng, T.W.; Yu, N.Y.; Seetharam, M.; Patel, S.H. Radiotherapy for malignant melanoma of the lacrimal sac. Rare Tumors 2020, 12, 2036361320971943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shao, J.W.; Yin, J.H.; Xiang, S.T.; He, Q.; Zhou, H.; Su, W. CT and MRI findings in relapsing primary malignant melanoma of the lacrimal sac: A case report and brief literature review. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Orgi, A.; El Ouadih, S.; Moussaoui, S.; Merzem, A.; Belgadir, H.; Amriss, O.; Moussali, N.; El Benna, N. Melanoma of the lacrimal sac: An extremely rare location From a radiologist perspective. Radiol. Case Rep. 2024, 19, 3982–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eng, V.A.; Lin, J.H.; Mruthyunjaya, P.; Erickson, B.P. Metastasis of Lung Adenocarcinoma to the Lacrimal Sac. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 37, S152–S154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitt, A.E.; Choi, C.J.; Johnson, T.E. Bilateral Leukemic Infiltration of the Lacrimal Sac in a Child. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 37, e28–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, L.; Kang, S.M. Lacrimal Sac Metastasis from Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 34, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakamura, Y.; Tanese, K.; Kameyama, K.; Ota, Y.; Fusumae, T.; Hirai, I.; Fukuda, K.; Funakoshi, T. Cutaneous eyelid melanoma with lacrimal sac metastasis: The potential role of lacrimal fluid as a metastatic pathway. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 2277–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacrimal Sac Tumors. American Academy of Ophthalmology, EyeWiki. Available online: https://eyewiki.org/Lacrimal_Sac_Tumors. (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Resteghini, C.; Baujat, B.; Bossi, P.; Franchi, A.; de Gabory, L.; Halamkova, J.; Haubner, F.; Hardillo, J.A.U.; Hermsen, M.A.; Iacovelli, N.A.; et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Sinonasal malignancy: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Benign and premalignant epithelial tumors |

| Squamous Papilloma |

| Inverted Papilloma |

| Malignant epithelial tumors |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Transitional Cell Carcinoma |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma |

| Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma |

| Other salivary gland-type carcinomas |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS |

| Melanocytic tumors (melanoma) |

| Hematolymphoid Tumors (e.g., B-cell Lymphoma) |

| Secondary Tumors |

| Extension from nearby tumors of skin, sinonasal cavities, ocular adnexa |

| Metastases from distant sites |

| Tumor-like lesions |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis |

| IgG4 related disease |

| Author, Year | Histotype | Histopathological Examination (HPE) | Immunocytochemistry (IHC) | Treatment and Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panda et al., 2022 [30] | Solitary fibrous tumor | Capsulated tumor with cellular neoplasm composed of spindloid to oval cells with mild degree of nuclear atypia arranged in sheets and fascicular pattern. | Cytoplasmic and membranous positivity for CD34, CD99, STAT-6, BCL-2 and weak to moderate positivity for smooth muscle actin (SMA). KI67 was 10% |

|

| Samaddar et al., 2021 [31] | Solitary fibrous tumor | FNAC *: Cohesive fragments and dispersed cells with pseudoacinar arrangement and interspersed slender branching vascular channels. Tumor cells are round, ovoid, and spindled with scant wispy cytoplasm and minimal nuclear atypia, stripped nuclei and scant collagenous stroma. | Nuclear reactivity for STAT6 |

|

| Sharma et al., 2020 [32] | Epithelial–Myoepithelial Carcinoma | 2-layered epithelium arranged in interconnecting nests, tubules, and gland-like structures. The inner layer was characterized by abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. The outer layer had less cytoplasm. The nuclei showed mild enlargement and pleomorphism. | The outer layer of myoepithelial cells was positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA), calponin, p63, and keratin 5/6. The inner layer of epithelial cells stained for keratin 7. |

|

| Almutairi et al., 2022 [33] | Oncocytoma | Epithelial cells arranged in an adenomatous fashion and in cords. Epithelial cells lining the acini were relatively benign and moderately eosinophilic. No mitotic figures or atypia. | CK18 positive in inner cells and P63 positive in outer cells. |

|

| Gupta et al., 2024 [34] | Primary anaplastic extramedullary plasmacytoma | Sheets of atypical plasma cells with eccentrically placed nuclei, with moderate nuclear polymorphism and prominent nucleoli | Membranous positivity for CD38, nuclear positivity for MUM1, and negativity for cytokeratin EBER-ISH. |

|

| Kumar et al., 2021 [35] | Angiofibroma | Tissue lined by pseudostratified columnar ciliated epithelium with focal area of squamous metaplasia. Underlying subepithelial tissue shows blood vessels with dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. The vessels are small and capillary sized lined with plump epithelial cells and surrounded by delicate fibrocellular stroma. | CD34 and SMA highlight the blood vessels and capillaries. KI67 < 2%. |

|

| Miller et al., 2020 [36] | Transitional cell carcinoma | Papillomatous lesion with both endophytic and exophytic features with extensive full thickness dysplasia and atypia with mitotic figures extending to near the surface. Basaloid cells with rare foci suggesting gland formation favoring transitional cell carcinoma. | FGFR3 positive |

|

| Dash et al., 2024 [37] | Hemangiopericytoma (probably to be recategorized as Solitary fibrous tumor) | Densely packed spindle cells with a prominent vascular pattern with tumor cells showing irregular shaped nuclei, small nucleoli, and ill-defined cytoplasmic borders. | Not used (STAT6 not assessed) |

|

| Seethapathi et al., 2021 [38] | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Malignant neoplasm comprising small round and spindle-shaped cells scattered in a loose stroma. Large multinucleated bizarre giant cells, atypical mitosis and polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. | Not used |

|

| Alam et al., 2020 [39] | Primary apocrine adenocarcinoma | Focal cribriform pattern of neoplastic cells, duct-like structures, infiltrating desmoplastic stroma with nuclear atypia in the tumor cells, and mitotic activity. Areas of decapitation secretion, highly suggestive of apocrine adenocarcinoma. | CKAE1/AE3, GCDFP15, CK7 positive CK20 negative KI67 was 18–20%. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Locatello, L.G.; Redolfi De Zan, E.; Marzolino, R.; Sowerby, L.J.; Tarantini, A.; Lanzetta, P.; Miani, C. Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Histotype-Driven Literature Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223718

Locatello LG, Redolfi De Zan E, Marzolino R, Sowerby LJ, Tarantini A, Lanzetta P, Miani C. Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Histotype-Driven Literature Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223718

Chicago/Turabian StyleLocatello, Luca Giovanni, Enrico Redolfi De Zan, Riccardo Marzolino, Leigh J. Sowerby, Anna Tarantini, Paolo Lanzetta, and Cesare Miani. 2025. "Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Histotype-Driven Literature Review" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223718

APA StyleLocatello, L. G., Redolfi De Zan, E., Marzolino, R., Sowerby, L. J., Tarantini, A., Lanzetta, P., & Miani, C. (2025). Lacrimal Sac Tumors: A Histotype-Driven Literature Review. Cancers, 17(22), 3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223718