1. Introduction

BC is among the most prevalent malignancies affecting women worldwide, and due to substantial progress in early detection and treatment, survival rates have markedly improved over recent decades [

1]. As survival outcomes continue to rise, QoL has emerged as a critical dimension of survivorship research and clinical care [

2]. Within this multidimensional construct, EF represents a central yet often under-examined domain [

2,

3]. EF captures several interrelated aspects of emotional life, including the ways individuals express, interpret, comprehend, respond to, and manage their emotions [

4]. In the context of BC, EF further encompasses affective well-being, emotional distress, fear of cancer recurrence, body image concerns, and the individual’s capacity for psychological adjustment throughout survivorship [

2]. Gaining a deeper understanding of EF trajectories is crucial for promoting comprehensive recovery and sustaining long-term QoL among BC survivors.

Growing evidence suggests that EF is not static but evolves dynamically over time following surgery, often following nonlinear trajectories shaped by surgical modality, age, and broader biopsychosocial factors [

3,

5,

6,

7]. For instance, a prospective cohort study in the Netherlands demonstrated that while EF tends to improve progressively after surgery, psychosocial well-being may decline—particularly among women who do not undergo reconstruction [

3]. Among BC patients, QoL follows a curvilinear trajectory, showing initial postoperative improvements that reach a peak around 31 to 54 months, after which it either stabilizes or gradually declines [

7].

Research underscores the heterogeneity of emotional adjustment among BC survivors [

3,

8]. Studies among older survivors have delineated distinct depressive symptom trajectories, revealing that although most patients maintain stable emotional profiles, a subset exhibits delayed recovery or increasing symptomatology over a three-year period—patterns strongly associated with lower social support and higher baseline anxiety [

6]. Insufficient family support has been associated with poorer psychosocial well-being trajectories during the first postoperative year among breast cancer survivors [

3].

Surgical modality also appears to influence emotional adjustment, with evidence suggesting that women undergoing breast reconstruction may experience more rapid improvements in EF compared with those receiving MA or BCS [

3]. Moreover, data indicate that younger (<50 years) women often report higher emotional distress compared to older survivors [

9]. Together, these studies suggest that EF trajectories are shaped by both treatment type and age-related psychosocial vulnerabilities. These findings highlight the need to examine EF longitudinally and to account for the influence of clinical and contextual factors across time.

Despite this emerging body of literature, critical knowledge gaps remain. Notably, few studies have synthesized longitudinal data to model the long-term, potentially nonlinear trajectories of EF beyond the initial 2–3 years after surgery [

2,

5,

6,

7]. Moreover, the moderating roles of surgical modality and age have not been comprehensively quantified across studies [

3,

7]. Addressing these gaps is essential for identifying periods of heightened emotional vulnerability, informing the timing and content of psychosocial interventions, and optimizing survivorship care strategies tailored to individual needs.

Understanding EF trajectories also holds significant clinical implications. Persistent emotional distress has been linked to poorer adherence to adjuvant therapies, increased healthcare utilization, and reduced overall well-being [

10,

11]. Integrating EF monitoring into survivorship care pathways may therefore enhance holistic recovery and long-term adaptation. A meta-analytic approach that synthesizes existing longitudinal evidence offers an opportunity to clarify these trajectories, uncover heterogeneity, and guide evidence-based, age- and treatment-specific psychosocial interventions.

Accordingly, this systematic review and meta-analysis sought to comprehensively synthesize longitudinal evidence on EF among BC survivors following surgical treatment. Specifically, the objectives were to: (1) characterize trajectories of EF over time after surgery, including potential nonlinear patterns; and (2) examine the moderating effects of surgical modality and age on these trajectories.

4. Discussion

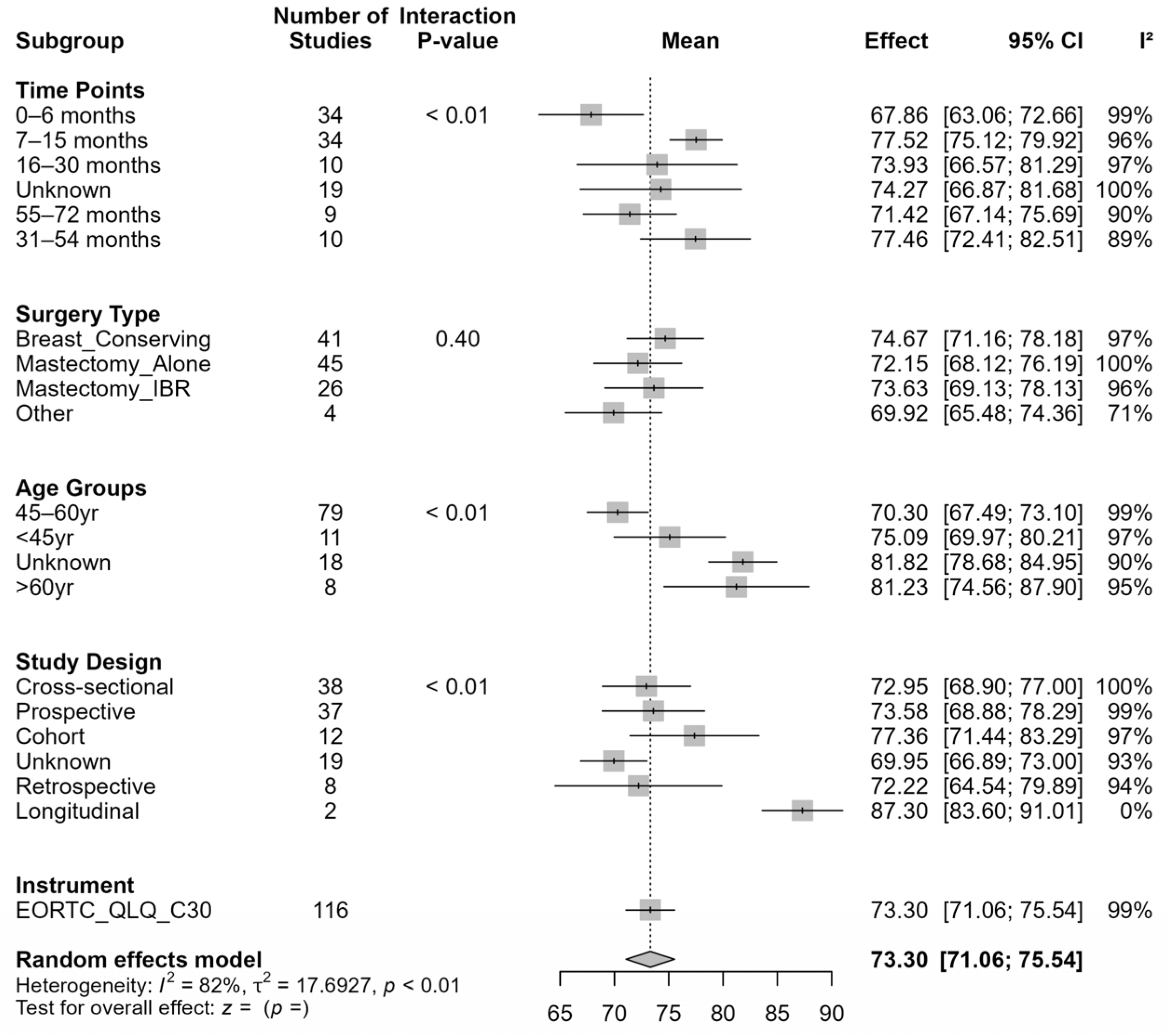

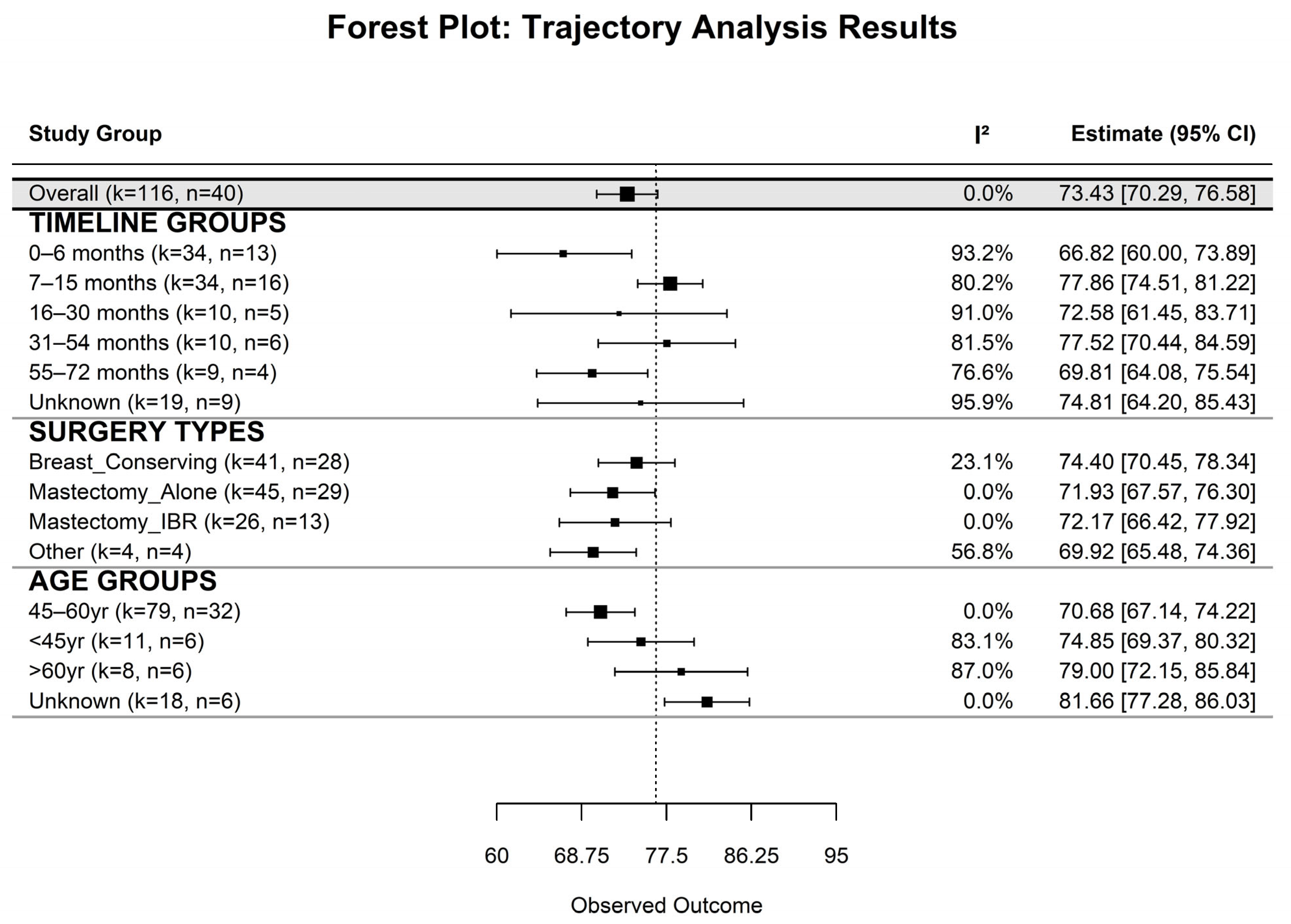

Our systematic review and meta-analysis provide robust evidence that EF among BC survivors is dynamic and influenced by time since surgery, surgical modality, and age. Overall, survivors reported moderately high EF (mean = 73.44), yet lower scores were observed during the early post-surgical period (first 6 months) and at later follow- up (55–72 months). This temporal pattern highlights both the initial adjustment challenges and potential long-term declines in EF, emphasizing the need for extended psychosocial support throughout survivorship. This sets the foundation for understanding how EF changes across time and under different clinical conditions.

In interpreting the changes observed in the EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in the present study, it is important to consider the concept of the minimally important difference (MID) —defined as the smallest change in a score that patients perceive as beneficial (or harmful) and which would lead to a change in patient management [

62]. Early guidelines for the QLQ-C30 often adopted a threshold of approximately ten points (on the 0–100 scale) for a clinically meaningful change across all scales [

63,

64].

More recent work, however, has shown that MIDs for the QLQ-C30 are not uniform: they vary by specific functional or symptom scale, by direction of change (improvement vs. deterioration), by cancer type, and by whether the change is within-group (pre-post) or between-group [

62]. For BC populations, estimated MIDs for within-group change generally range from 5 to 14 points for improvement and −4 to −14 points for deterioration across most functional and symptom scales of the QLQ-C30 [

65,

66]. These thresholds provide valuable context for interpreting whether observed changes in health-related QoL are not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful from the patient’s perspective.

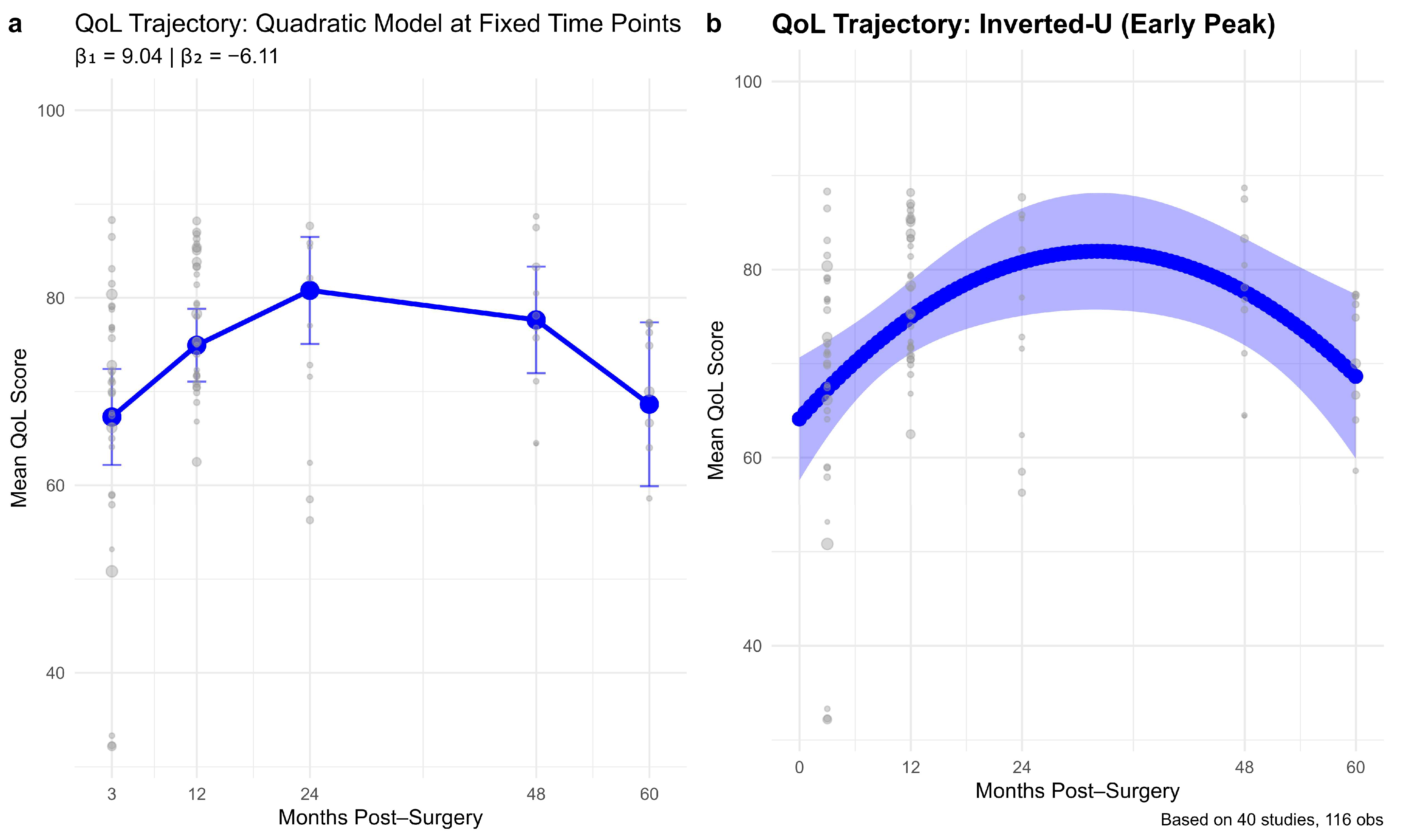

The longitudinal trajectory analyses revealed a consistent inverted-U pattern, with EF improving during the first 24–30 months post-surgery and gradually declining to near early post-surgical levels by 60 months. This pattern extends previous reports showing significant early psychological adaptation following surgery [

21,

49] and aligns with broader survivorship literature suggesting that later emotional vulnerability may emerge due to persistent concerns such as long-term treatment effects, fear of recurrence, and body image challenges [

2,

3,

5,

6]. Our Quadratic modeling effectively captured these dynamics, underscoring that early postoperative gains in EF may not be sustained in the long term. These findings reinforce calls for continuous emotional monitoring beyond the first two years and transition to a discussion of surgical determinants of EF.

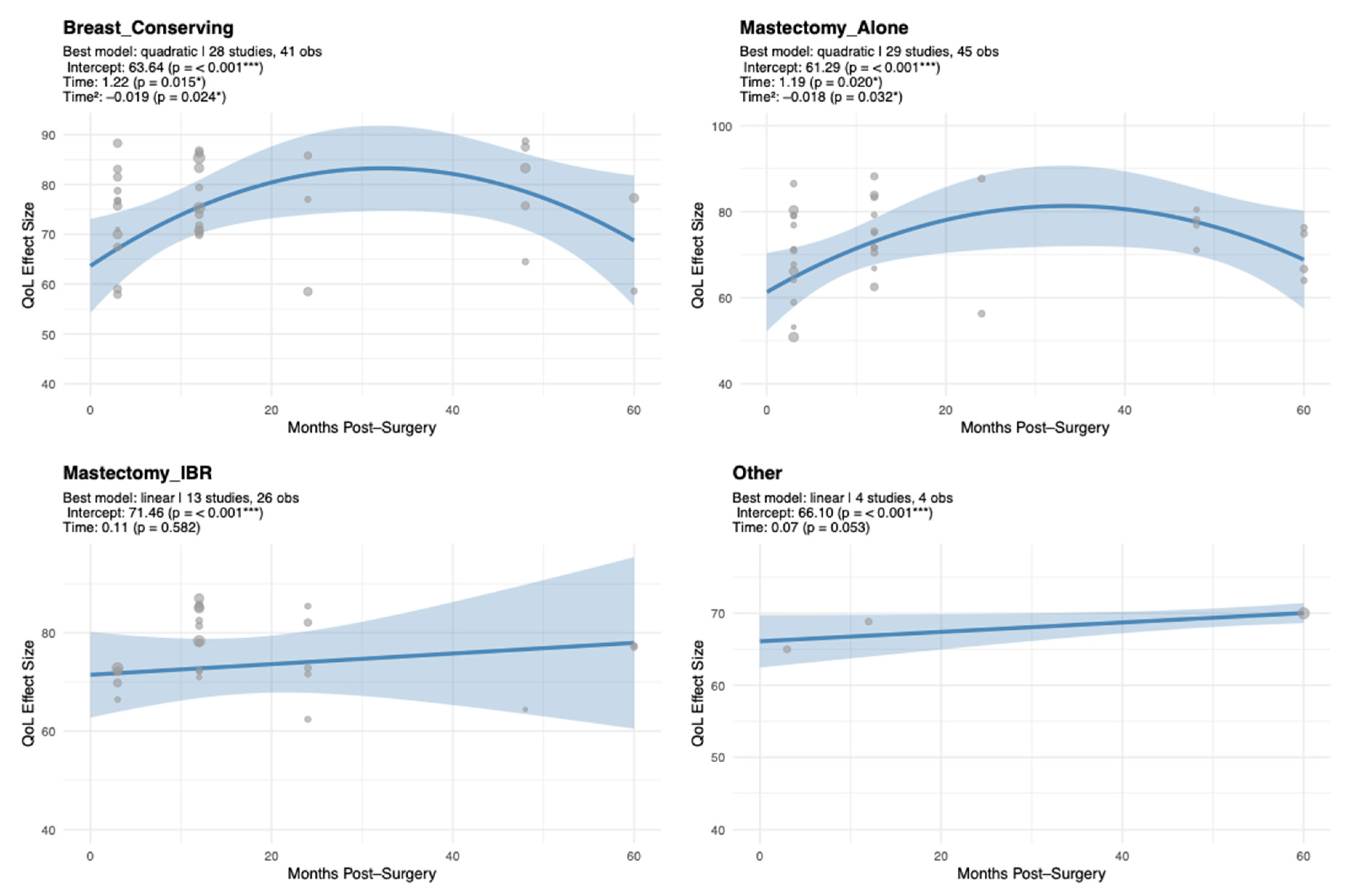

Surgical modality emerged as a key determinant of EF trajectories. Patients who underwent BCS or MA exhibited a characteristic inverted-U pattern, whereas those receiving Mx + IR or other procedures maintained relatively stable EF. These findings suggest that surgical type influences both the magnitude and temporal course of EF recovery, pointing to the value of procedure-specific psychosocial interventions. Consistent with prior findings, patients undergoing BCS generally reported higher EF compared to those undergoing MA, both with and without reconstruction [

16,

17,

20,

27]. While Hassan et al. (2024) demonstrated cross-sectional differences in QoL between mastectomy with and without reconstruction—showing slightly better overall QoL and social functioning among women without reconstruction—the study did not assess EF trajectories over time nor include a BCS group, limiting direct comparisons across modalities [

22]. Our meta-analysis adds longitudinal context, illustrating how EF evolves differently depending on surgical type.

Specifically, BCS and MA groups exhibited early improvements in EF followed by later stabilization or mild decline, whereas Mx + IR patients demonstrated more stable trajectories over time [

21,

54]. These findings suggest that the type of surgery shapes both the magnitude and temporal course of emotional recovery, highlighting the importance of procedure-specific psychosocial interventions. Building on these results, age also emerged as a significant moderator of emotional recovery.

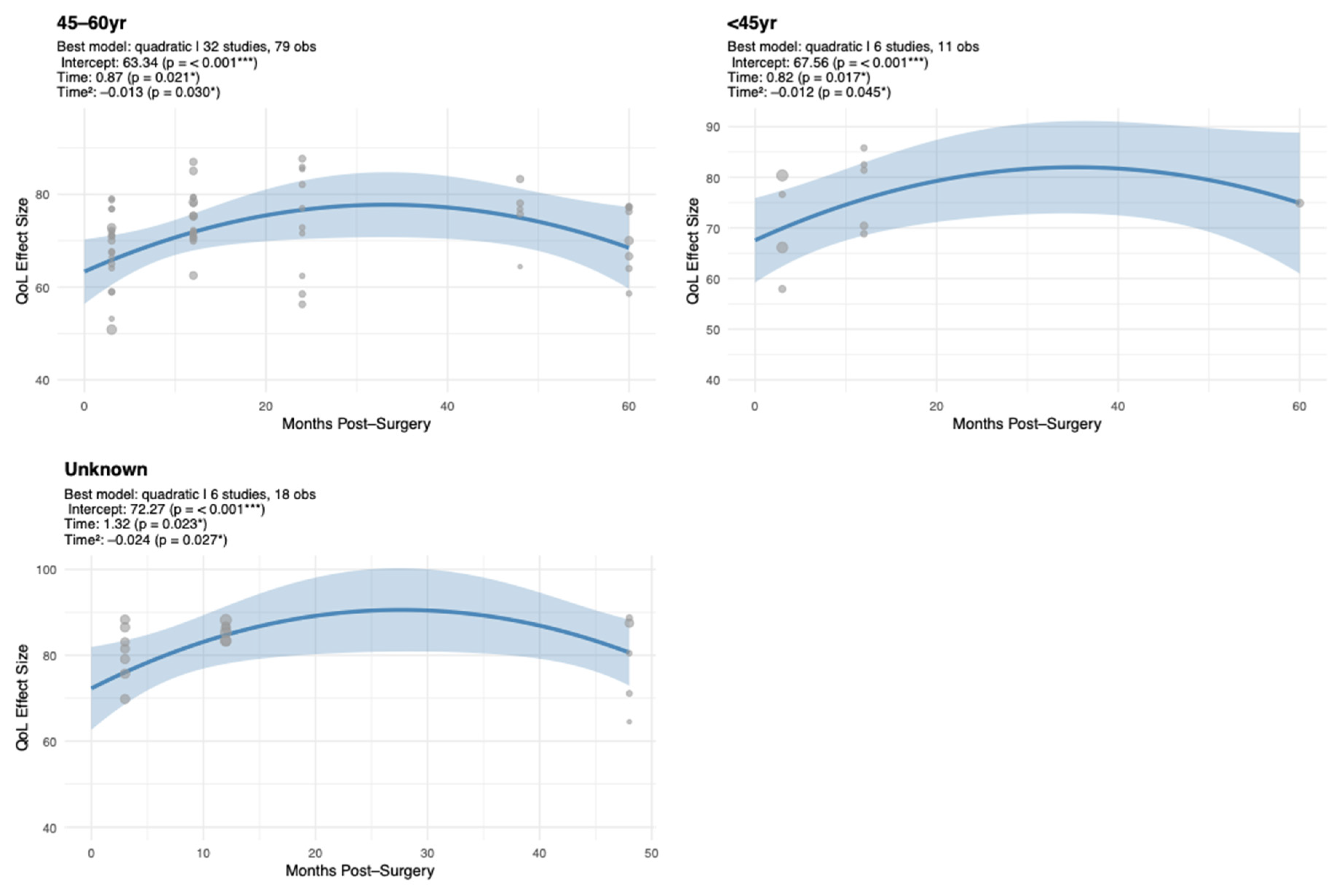

Our analysis demonstrated that age moderates EF recovery. Younger (<45 years) and middle-aged (45–60 years) patients experienced early improvements followed by gradual declines, whereas older patients (>60 years) maintained high and stable EF. These findings align with prior studies [

18,

28,

48] showing that younger and middle-aged women experience greater psychosocial distress compared to older patients, largely driven by heightened concerns about body image and social roles. Such distress may also stem from life-stage challenges, including fertility concerns, career disruption, and shifting family or social roles, highlighting the importance of addressing age-specific psychosocial dynamics. Younger and middle-aged survivors, in particular, experience unique emotional vulnerabilities related to role demands, body image, and life-stage transitions, underscoring the need for tailored counseling and survivorship planning.

Our meta-regression further highlighted that middle-aged patients are particularly vulnerable to long-term declines, and that MA is associated with significantly lower EF relative to BCS. This emphasizes the need for age-tailored interventions to optimize recovery of EF. Several studies also underline the interplay between EF and psychosocial factors such as body image, social support, and sexual functioning. For instance, Aerts et al. (2014) reported that women undergoing mastectomy experienced greater challenges in sexual and emotional functioning than those receiving BCS, highlighting the broader psychosocial consequences of surgery type [

17]. Similarly, Kouwenberg et al. (2020) and Moro-Valdezate et al. (2014) found that post-surgical complications and cosmetic outcomes significantly impacted emotional well-being, reinforcing the notion that clinical and patient-centered outcomes are closely linked in shaping long-term EF [

25,

26]. Collectively, these findings underscore the complex, time-dependent nature of EF recovery in BC survivors [

7], leading into the broader role of psychosocial resources.

Beyond surgical approaches, patient-reported EF and overall QoL are independently shaped by adjuvant therapies, with both endocrine therapy and chemotherapy producing lasting, domain-specific QoL impairments that persist for years following diagnosis [

67,

68]. Patients with lower cognitive functioning, adverse life experiences, and limited social support report significantly higher anxiety and depression during radiotherapy, highlighting the pivotal role of psychosocial and cognitive factors in emotional adaptation to treatment [

69]. Additionally, disease biology and burden markedly influence these outcomes, with more aggressive breast cancer subtypes consistently linked to poorer QoL and heightened psychosocial distress [

70].

Alongside biological and treatment-related influences, psychosocial factors play a pivotal role in shaping EF trajectories among BC survivors [

3,

41,

71,

72]. Studies have consistently demonstrated that emotional support, coping strategies, and social networks significantly influence psychological outcomes. For instance, Devarakonda et al. (2023) found that EF improved over time, particularly among survivors who were engaged in strong social support networks and utilized adaptive coping mechanisms, whereas limited support and maladaptive coping were linked to persistent distress [

3]. Similarly, Zamanian et al. (2021) demonstrated that higher perceived social support was associated with lower anxiety and depression in women with BC, and that adaptive coping mediated this relationship, highlighting the critical role of psychosocial resources in supporting long-term EF [

71]. These insights point toward the therapeutic potential of structured psychosocial interventions.

Indeed, evidence underscores the importance of structured psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive–behavioral therapy and supportive counseling, in improving emotional outcomes among cancer survivors, particularly when implemented early in survivorship [

72]. Moreover, fostering strong social networks and promoting adaptive coping skills may buffer against negative emotional impacts of treatment-related stressors, body image concerns, and fear of recurrence. Personalized approaches that consider age, surgical modality, social support, and life-stage-specific challenges are likely to be most effective in promoting sustained emotional recovery. Implementing such tailored psychosocial interventions within multidisciplinary cancer care may optimize long-term QoL and enhance overall survivorship outcomes.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This meta-analysis modeled long-term trajectories of EF in BC survivors across surgical modalities and age groups using multilevel random-effects models. Its robustness is supported by adherence to PRISMA guidelines, use of standardized EF measures (EORTC QLQ-C30). Nevertheless, heterogeneity in follow-up durations and reliance on a single EF instrument may have influenced pooled estimates. In addition, the use of aggregate-level data limited adjustment for key confounders such as adjuvant therapy and baseline psychological status, suggesting directions for methodological refinement in future research.

4.2. Future Directions

Future studies should clarify the mechanisms underlying the inverted-U trajectory of EF, focusing on factors contributing to late-phase declines. Biopsychosocial variables—such as fatigue, endocrine symptoms, fear of recurrence, and limited social support—likely interact over time to shape emotional adaptation. Given the increased vulnerability observed among middle-aged women, further research should address age-specific stressors, including caregiving demands, occupational strain, and menopausal transitions. Qualitative and mixed-methods approaches are recommended to capture nuanced emotional experiences and inform the design of targeted, age-sensitive psychosocial interventions, bridging research and practical survivorship care.

While psychosocial determinants play a critical role in EF outcomes, biomedical and treatment-related factors also contribute substantially. To capture the full complexity of these trajectories, future research should adopt an integrative approach that considers the cumulative and interactive effects of adjuvant therapies (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and endocrine therapy), tumor characteristics, and clinical prognostic factors (such as lymph node status and recurrence risk) on EF. Examining these variables in conjunction with surgical and psychosocial factors will be critical to elucidating the multidimensional pathways influencing recovery and long-term well-being among BC survivors.