Quality of Life and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Skull Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma Treated with Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Oncological Outcome Assessment

2.5. Toxicity Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

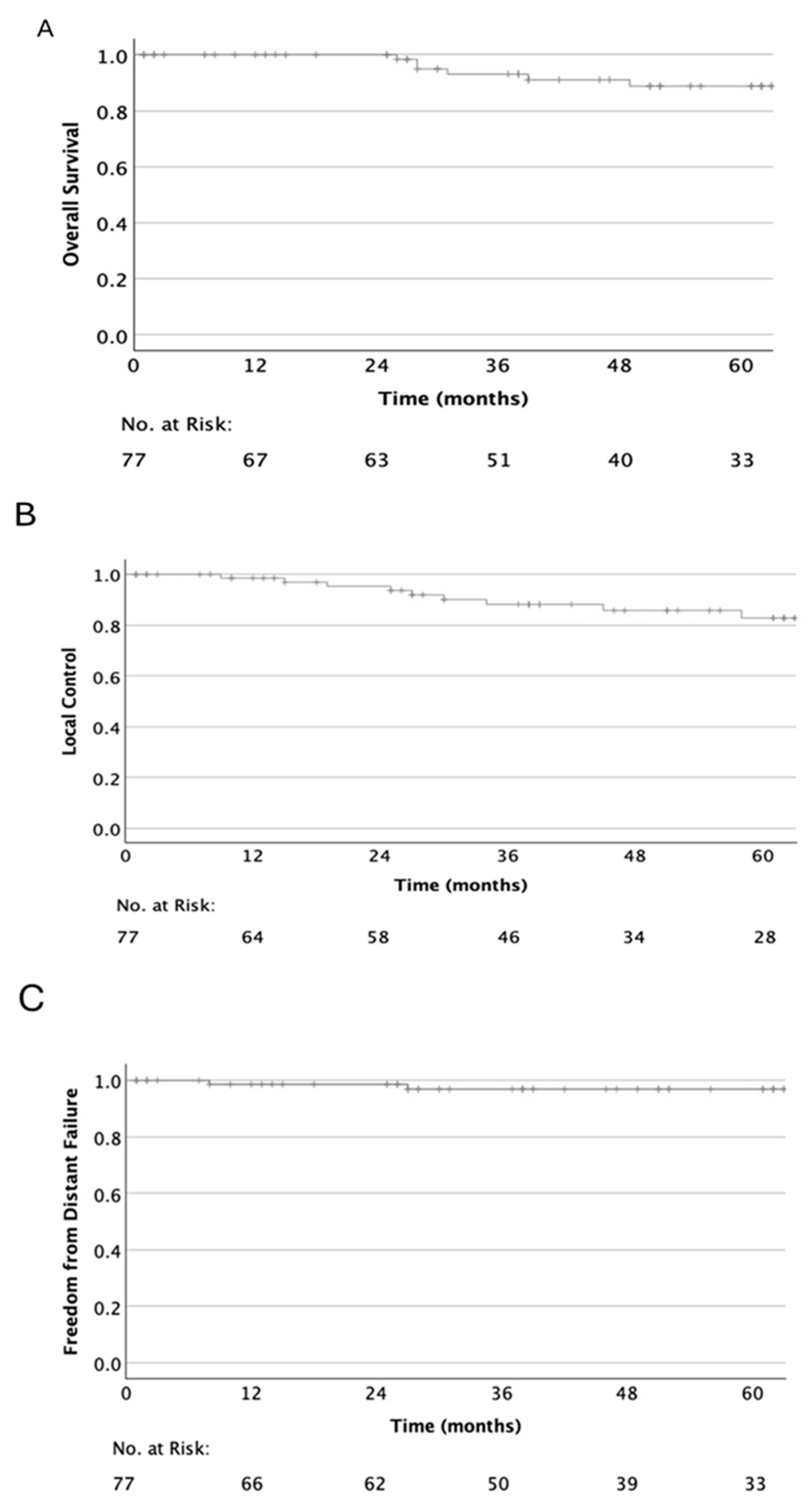

3.2. Oncological Outcome

3.3. Toxicity

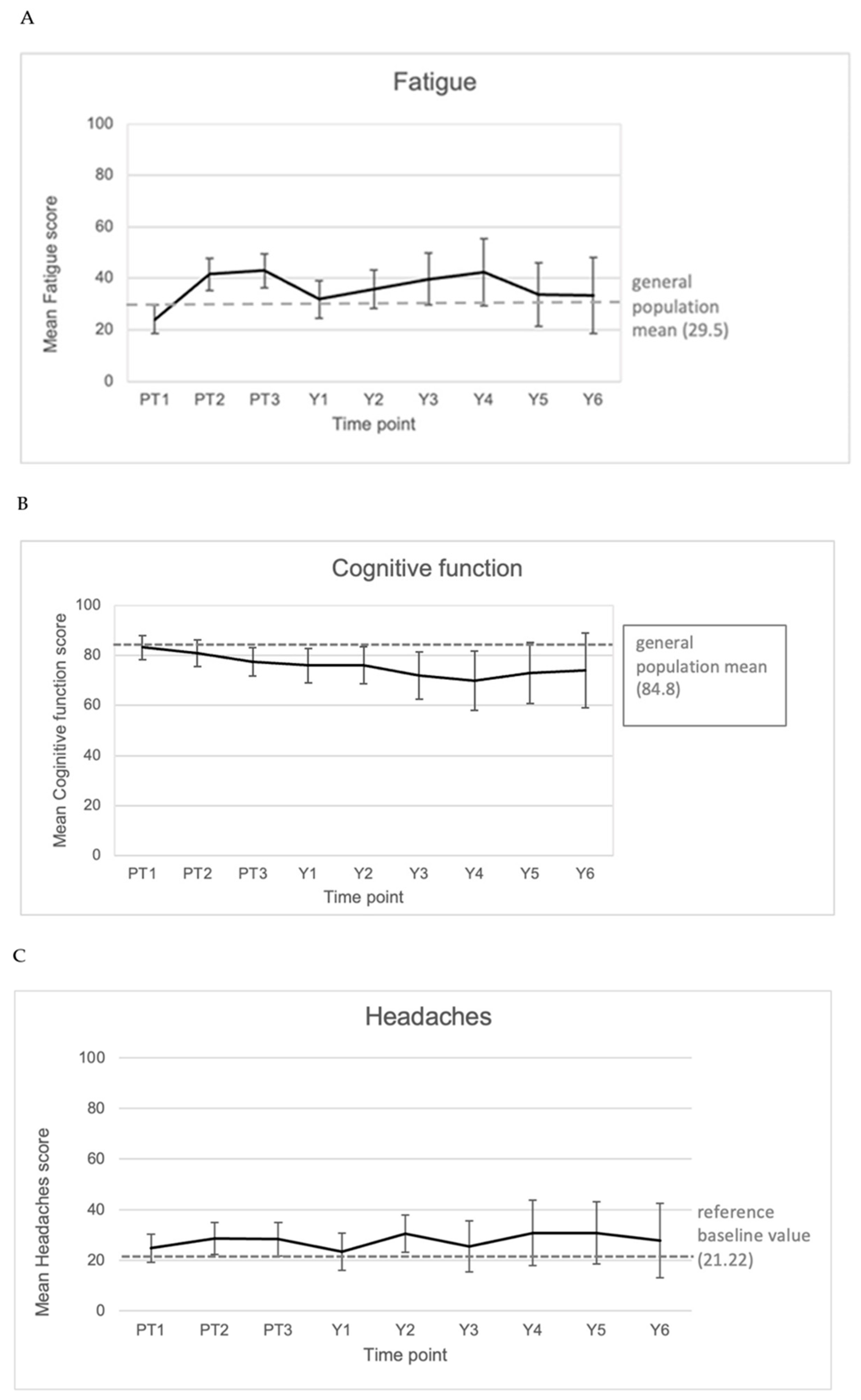

3.4. EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BN20 Outcome

3.4.1. Response Rates

3.4.2. C30 Global QoL

3.4.3. C30 Sum Score

3.4.4. Symptom and Function Scores

3.5. Correlation of Clinical Parameters to Reported Quality of Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pica, A.; Mirimanoff, R.-O. Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma of the Skull Base. In Management of Rare Adult Tumours; Belkacémi, Y., Mirimanoff, R.-O., Ozsahin, M., Eds.; Springer: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 51–56. ISBN 978-2-287-92246-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, H.; Iyer, A.; Lunsford, L.D. Skull Base Chondrosarcoma Radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 2014, 61, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.C.; Malyapa, R.; Albertini, F.; Bolsi, A.; Kliebsch, U.; Walser, M.; Pica, A.; Combescure, C.; Lomax, A.J.; Schneider, R. Long Term Outcomes of Patients with Skull-Base Low-Grade Chondrosarcoma and Chordoma Patients Treated with Pencil Beam Scanning Proton Therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2016, 120, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Khang, S.K.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, C.J. Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas of the Skull Base: Comparative Analysis of Clinical Results in 30 Patients. Neurosurg. Rev. 2008, 31, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.C.; Lim, P.S.; Tran, S.; Walser, M.; Bolsi, A.; Kliebsch, U.; Beer, J.; Bachtiary, B.; Lomax, T.; Pica, A. Proton therapy for brain tumours in the area of evidence-based medicine. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, E.B.; Loredo, L.N.; Slater, J.D.; Devries, A.; Grove, R.I.; Schaefer, R.A.; Rosenberg, A.E.; Slater, J.M. Proton Radiation Therapy for Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas of the Skull Base. J. Neurosurg. 1999, 91, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, C.E.; Holtzman, A.L.; Rotondo, R.; Rutenberg, M.S.; Mendenhall, W.M. Proton Therapy for Skull Base Tumors: A Review of Clinical Outcomes for Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas. Head Neck. 2019, 41, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.M.; Gidley, P.W.; Meis, J.M.; Grosshans, D.R.; Bell, D.; DeMonte, F. Multimodality Treatment of Skull Base Chondrosarcomas: The Role of Histology Specific Treatment Protocols. Neurosurgery 2017, 81, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, S.; Temkin, N.; Ramanathan, D.; Sekhar, L.N. Current Comprehensive Management of Cranial Base Chordomas: 10-Year Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 115, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohman, L.-E.; Koch, M.; Bailey, R.L.; Alonso-Basanta, M.; Lee, J.Y.K. Skull Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma: Influence of Clinical and Demographic Factors on Prognosis: A SEER Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.C.; Rutz, H.P.; Pedroni, E.S.; Bolsi, A.; Timmermann, B.; Verwey, J.; Lomax, A.J.; Goitein, G. Results of Spot-Scanning Proton Radiation Therapy for Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma of the Skull Base: The Paul Scherrer Institut Experience. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 63, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Vischioni, B.; Fiore, M.R.; Vitolo, V.; Fossati, P.; Iannalfi, A.; Tuan, J.K.L.; Orecchia, R. Quality of Life in Patients with Chordomas/Chondrosarcomas during Treatment with Proton Beam Therapy. J. Radiat. Res. 2013, 54, i43–i48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Claassens, L.; Aaronson, N.K.; Coens, C.; Mauer, M.; Osoba, D.; Stupp, R.; Mirimanoff, R.O.; van den Bent, M.J.; Bottomley, A. An International Validation Study of the EORTC Brain Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-BN20) for Assessing Health-Related Quality of Life and Symptoms in Brain Cancer Patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayers, P.M. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual; European Organization for Research on Treatment of Cancer Study Group on Quality of Life: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; ISBN 2930064226. [Google Scholar]

- Giesinger, J.M.; Kieffer, J.M.; Fayers, P.M.; Groenvold, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Scott, N.W.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Velikova, G.; Aaronson, N.K. Replication and Validation of Higher Order Models Demonstrated That a Summary Score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 Is Robust. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osoba, D.; Aaronson, N.K.; Muller, M.; Sneeuw, K.; Hsu, M.A.; Yung, W.K.; Brada, M.; Newlands, E. The development and psychometric validation of a brain cancer quality-of-life questionnaire for use in combination with general cancer-specific questionnaires. Qual. Life Res. 1996, 5, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.T.; Dunn, R.L.; Sandler, H.M.; McLaughlin, P.W.; Montie, J.E.; Litwin, M.S.; Nyquist, L.; Sanda, M.G. Comprehensive Comparison of Health-Related Quality of Life after Contemporary Therapies for Localized Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubels, R.J.; Mokhles, S.; Andrinopoulou, E.R.; Braat, C.; van der Voort van Zyp, N.C.; Aluwini, S.; Aerts, J.G.; Nuyttens, J.J. Quality of Life during 5 Years after Stereotactic Radiotherapy in Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiat. Oncol. 2015, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, P.H.; Gottlieb, A.; Kramer, S.; Danoff, B. Quality of life after radiation therapy: A study of 309 cancer survivors. Soc. Indic. Res. 1982, 10, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, C.L.; Routledge, J.A.; Farnell, D.J.J.; Swindell, R.; Davidson, S.E. The Impact of Radiotherapy Late Effects on Quality of Life in Gynaecological Cancer Patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2009, 100, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours: Revised RECIST Guideline (Version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, S.; Liegl, G.; Petersen, M.A.; Aaronson, N.K.; Costantini, A.; Fayers, P.M.; Groenvold, M.; Holzner, B.; Johnson, C.D.; Kemmler, G.; et al. General Population Normative Data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire Based on 15,386 Persons across 13 European Countries, Canada and the Unites States. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 107, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, A.; Chin, A.T.; Wagner, J.R.; Kunwar, S.; Ames, C.; Chou, D.; Barani, I.; Parsa, A.T.; McDermott, M.W.; Benet, A.; et al. Factors Predicting Recurrence After Resection of Clival Chordoma Using Variable Surgical Approaches and Radiation Modalities. Neurosurgery 2015, 76, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basler, L.; Poel, R.; Schröder, C.; Bolsi, A.; Lomax, A.; Tanadini-Lang, S.; Guckenberger, M.; Weber, D.C. Dosimetric Analysis of Local Failures in Skull-Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma Following Pencil Beam Scanning Proton Therapy. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, T.K.; Sørlie, A.; Sjaavik, K.; Nygaard, Ø.P.; Ingebrigtsen, T. Would Loss to Follow-up Bias the Outcome Evaluation of Patients Operated for Degenerative Disorders of the Lumbar Spine? Acta Orthop. 2011, 82, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeze, S.G.C.; Mackeprang, P.-H.; De Angelis, C.; Pica, A.; Bachtiary, B.; Kliebsch, U.L.; Weber, D.C. A Prospective Study on Health-Related Quality of Life and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Adult Brain Tumor Patients Treated with Pencil Beam Scanning Proton Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, I.; Seibolt, M.; Zalaman, I.M.; Dietz, K.; Plinkert, P.K.; Maassen, M.M. Lebensqualität bei Patienten mit Oropharynxkarzinom. Das Geschlecht beeinflusst die subjektive Bewertung [Quality of life in patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma. Gender influences the subjective evaluation]. HNO 2006, 54, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geue, K.; Sender, A.; Schmidt, R.; Richter, D.; Hinz, A.; Schulte, T.; Brähler, E.; Stöbel-Richter, Y. Gender-Specific Quality of Life after Cancer in Young Adulthood: A Comparison with the General Population. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehlen, S.; Hollenhorst, H.; Schymura, B.; Herschbach, P.; Aydemir, U.; Firsching, M.; Dühmke, E. Psychosocial Stress in Cancer Patients during and after Radiotherapy. Strahlenther. Und Onkol. 2003, 179, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaldi, R.; Roussel, L.-M.; Gal, J.; Scheller, B.; Chamorey, E.; Schiappa, R.; Lasne-Cardon, A.; Louis, M.-Y.; Culié, D.; Dassonville, O.; et al. Correlations between Long-Term Quality of Life and Patient Needs and Concerns Following Head and Neck Cancer Treatment and the Impact of Psychological Distress. A Multicentric Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 2437–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosser, G.; McManus, P.; Munzenrider, J.; Austin-Seymour, M.; Fullerton, B.; Adams, J.; Urie, M.M. Neuropsychological Function in Adults after High Dose Fractionated Radiation Therapy of Skull Base Tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1997, 38, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, B.D.; Weimer, J.; Choi, C.J.; Bradley, C.J.; Bender, C.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Gardner, P.; Sherwood, P.R. Work Productivity and Neuropsychological Function in Persons with Skull Base Tumors. Neurooncol. Pract. 2014, 1, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakash, R.A.; Hutton, J.L.; Lamb, S.E.; Gates, S.; Fisher, J. Response and non-response to postal questionnaire follow-up in a clinical trial--a qualitative study of the patient’s perspective. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Median (Range) or Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Included | 77 | |

| Age [years] | Median | 50.0 |

| Range | 18.8–79.5 | |

| Sex | Male | 31 (40.3%) |

| Female | 46 (59.7%) | |

| Histology | Ch | 48 (62.3%) |

| ChSa | 29 (37.7%) | |

| Compression | Brainstem | 9 (11.7%) |

| Optic apparatus | 22 (28.6%) | |

| Resection status | GTR | 22 (28.6%) |

| Subtotal | 52 (67.5%) | |

| Biopsy only | 3 (3.9%) | |

| GTV size [cc] | Median | 8.4 |

| Range | 0.3–96.1 | |

| PT dose [Gy (RBE)] | Median | 74 |

| Range | 68–75 | |

| Category | Cohort 2016 | Cohort 2023 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | N = 222 | N = 77 | ||

| Age [years] | Mean | 42.8 | 50.7 | 0.001 |

| Sex [%] | Male | 52.7 | 40.3 | 0.06 |

| Female | 47.3 | 59.7 | ||

| Compression of any type (brainstem or optic apparatus) [%] | Yes | 50.9 | 36.4 | |

| No | 49.1 | 63.7 | 0.03 | |

| Resection status [%] | GTR | 3.2 | 28.6 | <0.001 |

| Subtotal | 96.8 | 71.4 | ||

| GTV size [cc] | Mean | 35.7 | 15.5 | <0.001 |

| Friedman Test Significance (p-Value) | PT1 | PT3 | Y1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global QoL | C30_SumSc | Neurological Symptoms | Global QoL | C30_SumSc | Neurological Symptoms | Global QoL | C30_SumSc | Neurological Symptoms | |

| Sex (male/female) | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.209 | 0.058 | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.048 | 0.015 |

| Age | 0.473 | 0.286 | 0.821 | 0.526 | 0.946 | 0.338 | 0.844 | 0.881 | 0.664 |

| Resection status (GTR/subtotal) | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.034 | 0.06 | 0.015 |

| Pre-PT CNS symptoms | 0.642 | 0.934 | 0.912 | 0.186 | 0.316 | 0.461 | 0.539 | 0.878 | 0.539 |

| GTV volume | 0.331 | 0.639 | 0.55 | 0.178 | 0.208 | 0.791 | 0.696 | 0.592 | 0.702 |

| Dose | 0.661 | 0.821 | 0.881 | 0.278 | 0.531 | 0.179 | 0.703 | 0.692 | 0.597 |

| Acute toxicities | 0.745 | 0.267 | 0.825 | 0.147 | 0.055 | 0.539 | 0.966 | 0.165 | 0.233 |

| Late toxicities | 0.833 | 0.674 | 0.839 | 0.176 | 0.995 | 0.646 | 0.157 | 0.523 | 0.91 |

| PD | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.039 | 0.053 | 0.02 | 0.017 | 0.478 | 0.038 | 0.039 |

| Friedman Test Correlation Coefficient | PT1 | PT3 | Y1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global QoL | C30_SumSc | Neurological Symptoms | Global QoL | C30_SumSc | Neurological Symptoms | Global QoL | C30_SumSc | Neurological Symptoms | |

| Sex (male/female) | 0.296 | 0.369 | −0.257 | 0.148 | 0.222 | −0.251 | 0.345 | 0.263 | −0.322 |

| Age | −0.085 | −0.126 | 0.027 | −0.075 | −0.008 | 0.113 | −0.027 | 0.02 | 0.059 |

| Resection status (GTR/subtotal) | 0.34 | 0.372 | −0.311 | 0.358 | 0.366 | −0.347 | 0.281 | 0.251 | −0.321 |

| Pre-PT CNS symptoms | 0.055 | 0.01 | −0.013 | 0.155 | 0.118 | −0.087 | 0.083 | −0.021 | −0.083 |

| GTV volume | −0.137 | −0.067 | 0.085 | −0.188 | −0.176 | 0.037 | 0.06 | 0.082 | −0.059 |

| Dose | 0.052 | 0.027 | −0.018 | −0.128 | −0.074 | 0.158 | 0.052 | 0.054 | 0.072 |

| Acute toxicities | 0.039 | −0.131 | 0.026 | −0.17 | −0.224 | 0.073 | −0.006 | −0.187 | 0.161 |

| Late toxicities | 0.025 | −0.05 | −0.025 | 0.159 | 0.001 | −0.054 | 0.19 | 0.086 | −0.015 |

| PD | −0.301 | −0.28 | 0.241 | −0.226 | −0.269 | 0.277 | −0.096 | −0.275 | 0.274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bryjova, K.; Mackeprang, P.-H.; Leiser, D.; Weber, D.C. Quality of Life and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Skull Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma Treated with Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 3651. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223651

Bryjova K, Mackeprang P-H, Leiser D, Weber DC. Quality of Life and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Skull Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma Treated with Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3651. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223651

Chicago/Turabian StyleBryjova, Katarina, Paul-Henry Mackeprang, Dominic Leiser, and Damien C. Weber. 2025. "Quality of Life and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Skull Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma Treated with Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3651. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223651

APA StyleBryjova, K., Mackeprang, P.-H., Leiser, D., & Weber, D. C. (2025). Quality of Life and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Skull Base Chordoma and Chondrosarcoma Treated with Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy. Cancers, 17(22), 3651. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223651