The Real-World Impact of PARP Inhibitor Maintenance Therapy in High Grade Serous Tubo-Ovarian and Peritoneal Cancers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

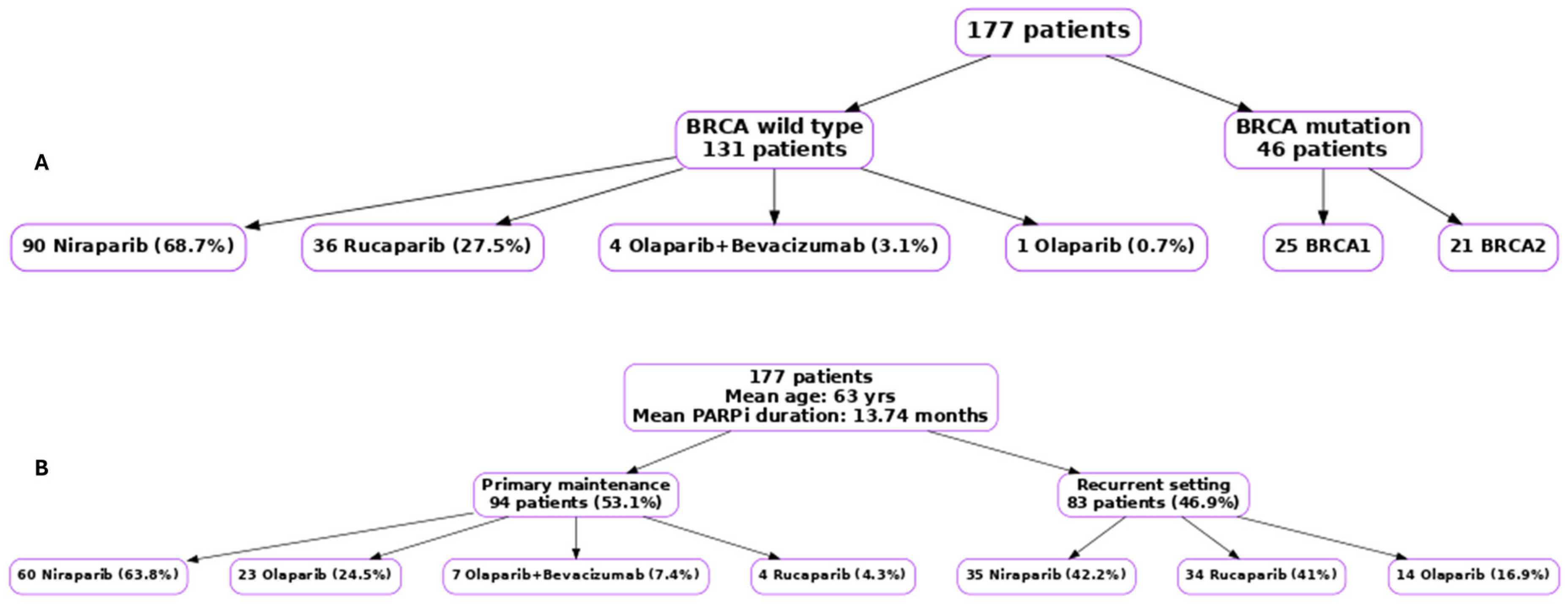

3. Results

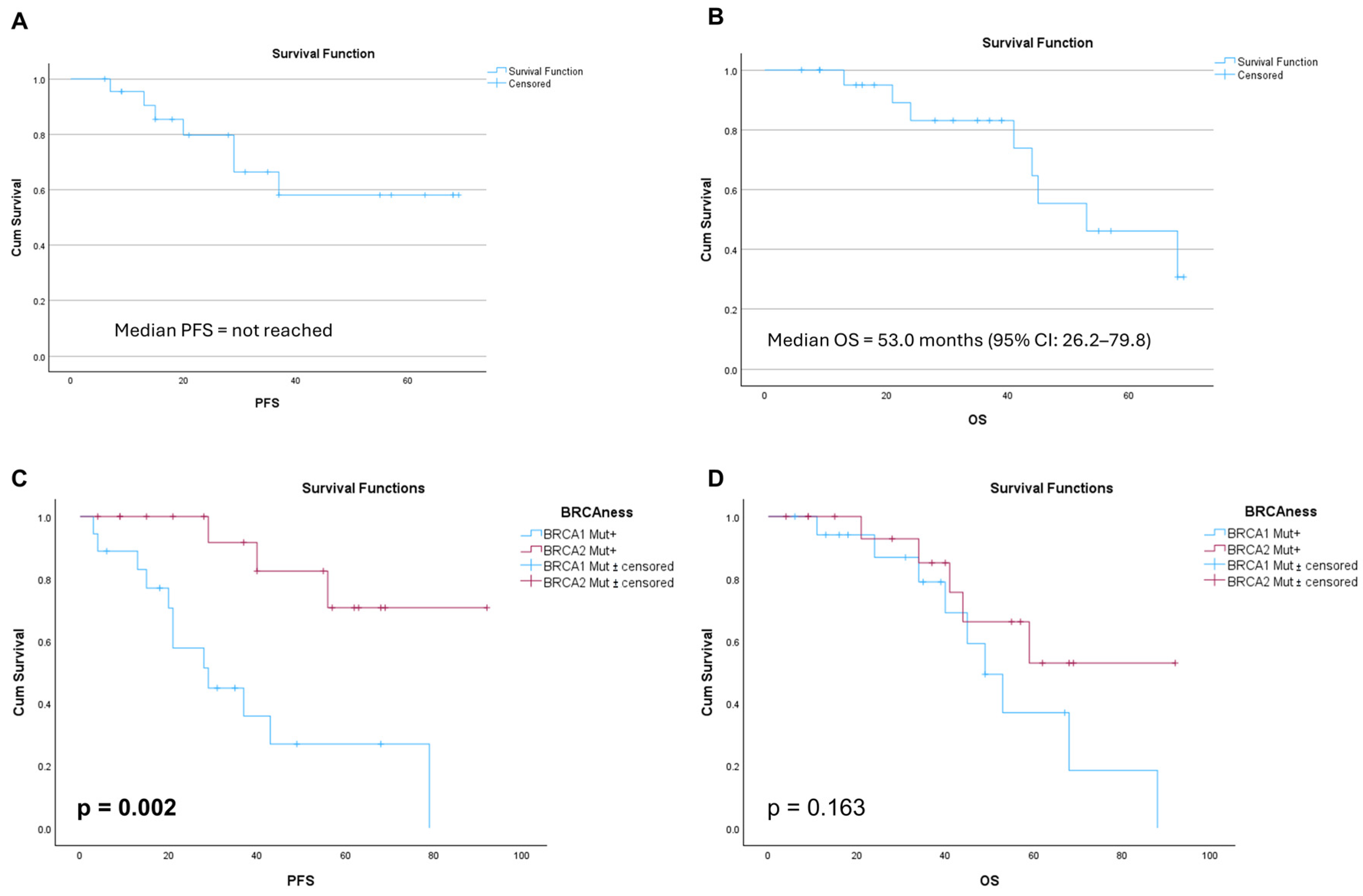

3.1. Survival Outcomes in Patients with Germline BRCA Mutations Receiving Olaparib as Primary Maintenance Therapy

3.2. Survival Outcomes for Patients Who Received Olaparib as Maintenance Therapy in the Recurrent Disease Setting

3.3. Survival Outcomes in BRCA Wild Type Receiving Niraparib Primary Maintenance

3.4. Survival Outcomes in Patients Who Received Primary Surgery or Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Surgery

3.5. Survival Outcomes for Olaparib, Niraparib, and Rucaparib in the Recurrent Setting

3.6. Survival Outcomes in HR-Deficient (HRD) or HR-Proficient (HRP) Tumours

3.7. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian cancers |

| HRD | Homologous recombination deficiency |

| HRP | Homologous recombination proficiency |

| PFS | Progression free survival |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PARP | Poly-ADP ribose polymerase |

| GMSA | Genomic Medicine Service Alliance |

| NHS | National Health Service |

References

- CRUK. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/ovarian-cancer (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Lheureux, S.; Braunstein, M.; Oza, A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piver, M.S. Treatment of ovarian cancer at the crossroads: 50 years after single-agent melphalan chemotherapy. Oncology 2006, 20, 1156–1158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drew, Y. The development of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: From bench to bedside. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113 (Suppl. S1), S3–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Parmigiani, G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Gajjar, K.; Madhusudan, S. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor therapy and mechanisms of resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1414112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Seneviratne, N.; Tosun, C.; Madhusudan, S. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Mechanisms of resistance and implications to therapy. DNA Repair 2025, 149, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, R.; Kraus, W.L. The PARP side of the nucleus: Molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S.; Brownlie, J.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; Mongan, N.P.; Rakha, E.A.; Madhusudan, S. Evolving DNA repair synthetic lethality targets in cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2022, 42, BSR20221713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Lord, C.J.; Serra, V.; Tutt, A.; Balmana, J.; Castroviejo-Bermejo, M.; Cruz, C.; Oaknin, A.; Kaye, S.B.; de Bono, J.S. A decade of clinical development of PARP inhibitors in perspective. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilie, P.G.; Tang, C.; Mills, G.B.; Yap, T.A. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, J.; Huang, S.Y.; Das, B.B.; Renaud, A.; Zhang, Y.; Doroshow, J.H.; Ji, J.; Takeda, S.; Pommier, Y. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5588–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Kaye, S.; Banerjee, S. Delivering widespread BRCA testing and PARP inhibition to patients with ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Olaparib for Maintenance Treatment of BRCA Mutation-Positive Advanced Ovarian, Fallopian Tube or Peritoneal Cancer After Response to FIRST-Line Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. [TA962]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta962 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Niraparib for Maintenance Treatment of Advanced Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Peritoneal Cancer After Response to First-Line Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. [TA673]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta673 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Rucaparib for Maintenance Treatment of Advanced Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Peritoneal Cancer After Response to First-Line Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. [TA1055]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta1055 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Banerjee, S.; Moore, K.N.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; et al. Maintenance olaparib for patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation (SOLO1/GOG 3004): 5-year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSilvestro, P.; Banerjee, S.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; et al. Overall Survival With Maintenance Olaparib at a 7-Year Follow-Up in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer and a BRCA Mutation: The SOLO1/GOG 3004 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; Sonke, G.S.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSilvestro, P.; Colombo, N.; Scambia, G.; Kim, B.G.; Oaknin, A.; Friedlander, M.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Floquet, A.; Leary, A.; Sonke, G.S.; et al. Efficacy of Maintenance Olaparib for Patients With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer With a BRCA Mutation: Subgroup Analysis Findings From the SOLO1 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3528–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloman, W.K. Unraveling the mechanism of BRCA2 in homologous recombination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tao, L.; Dai, H.; Gong, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Xiang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Deng, L. BRCA1 Versus BRCA2 and PARP Inhibitors Efficacy in Solid Tumors:A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 718871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, C.; Fagotti, A.; Fruscio, R.; Cassani, C.; Incorvaia, L.; Perri, M.T.; Sassu, C.M.; Camnasio, C.A.; Giudice, E.; Minucci, A.; et al. Benefit from maintenance with PARP inhibitor in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer according to BRCA1/2 mutation type and site: A multicenter real-world study. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Pothuri, B.; Vergote, I.; DePont Christensen, R.; Graybill, W.; Mirza, M.R.; McCormick, C.; Lorusso, D.; Hoskins, P.; Freyer, G.; et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2391–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Ding, L.; Tian, Y.; Bi, M.; Han, N.; Wang, L. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of PARP Inhibitors as Maintenance Therapy in Platinum Sensitive Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: A Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 573801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Pautier, P.; Pignata, S.; Perol, D.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Berger, R.; Fujiwara, K.; Vergote, I.; Colombo, N.; Maenpaa, J.; et al. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2416–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahner, S.H.F.; Salehi, S.; Reuss, A.; Guyon, F.; Du Bois, A.; Harter, P.; Fotopoulou, C.; Querleu, D.; Mosgaard, B.J. TRUST: Trial of radical upfront surgical therapy in advanced ovarian cancer (ENGOT-ov33/AGO-OVAR OP7). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43 (Suppl. S17), LBA5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loverro, M.; Marchetti, C.; Salutari, V.; Giannarelli, D.; Vertechy, L.; Capomacchia, F.M.; Caricato, C.; Campitelli, M.; Panico, C.; Avesani, G.; et al. Real-world outcomes of PARP inhibitor maintenance in advanced ovarian cancer: A focus on disease patterns and treatment modalities at recurrence. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Qiu, S.; Wu, X.; Miao, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, D.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Niraparib as First-Line Maintenance Treatment for Patients with Advanced Ovarian Cancer: Real-World Data from a Multicenter Study in China. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.E.; Hood, A.; Ahmad, H.; Altwerger, G. Real-World Efficacy and Safety of PARP Inhibitors in Recurrent Ovarian Cancer Patients With Somatic BRCA and Other Homologous Recombination Gene Mutations. Ann. Pharmacother. 2023, 57, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.L.; Quintanilha, J.C.F.; Danziger, N.; Li, G.; Sokol, E.; Schrock, A.B.; Ebot, E.; Bhardwaj, N.; Norris, T.; Afghahi, A.; et al. Effectiveness of PARP Inhibitor Maintenance Therapy in Ovarian Cancer by BRCA1/2 and a Scar-Based HRD Signature in Real-World Practice. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4644–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuninetti, V.; Marin-Jimenez, J.A.; Valabrega, G.; Ghisoni, E. Long-term outcomes of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Survival, adverse events, and post-progression insights. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippstein, N.; Zemmour, C.; Rodrigues, M.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Gladieff, L.; Pautier, P.; Frenel, J.S.; Costaz, H.; Lebreton, C.; Pomel, C.; et al. PARP inhibitors as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer after platinum-sensitive recurrence: Real-world experience from the Unicancer network. Oncologist 2025, 30, oyaf075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uekusa, R.; Yokoi, A.; Watanabe, E.; Yoshida, K.; Yoshihara, M.; Tamauchi, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Ikeda, Y.; Yoshikawa, N.; Niimi, K.; et al. Safety assessments and clinical features of PARP inhibitors from real-world data of Japanese patients with ovarian cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roufai, D.B.; Toth, R.; Palo, U.; Scaglione, G.; Palacios, A.T.; Novak, Z.; El Hajj, H.; Shushkevich, A.; Ledermann, J. Mechanisms of drug resistance: PARP inhibitors, antibody-drug-conjugates, and immunotherapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q. Navigating PARP Inhibitor Resistance in Ovarian Cancer: Bridging Mechanistic Insights To Clinical Translation. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2025, 26, 797–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, P.; Tang, J.; Yang, S.; Nicot, C.; Guan, Z.; Li, X.; Tang, H. Clinical approaches to overcome PARP inhibitor resistance. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean age in years(min, max) |

| 63.06 (28, 88) |

| Duration of maintenance Rx in months, mean (min, max) |

| 13.74 (0, 63) |

| Median follow-up time (months) |

| 28 (months) |

| BRCA mutation, No. (%) |

| Wild type 131 (74%) |

| BRCA1 + 25 (14.1%) |

| BRCA2 + 21 (11.9%) |

| HRD, No. (%) |

| HR-deficient 20 (11.3%) |

| HRD proficient 19 (10.7%) |

| Not available 138 (78%) |

| PARPI No. (%) |

| Olaparib 37 (20.9%) |

| Niraparib 95 (53.7%) |

| Rucaparib 38 (21.5%) |

| Olaparib + Bevacizumab 7 (4%) |

| PARPI Rx setting, No. (%) |

| Primary maintenance 94 (53.1%) |

| Recurrence 83 (46.9%) |

| BMI, No. (%) |

| < 25, 61 (34.5%) |

| ≥ 25, 116 (65.5%) |

| Surgical intervention, No. (%) |

| Upfront surgery 14 (17.5%) |

| Interval debulking surgery 62 (77.5%) |

| Inoperable 4 (5%) |

| FIGO stage, No. (%) |

| I, 4/177 (2.25%) |

| II, 2/177 (1.12%) |

| III, 101/177 (57.06%) |

| IV, 70/177 (39.5%) |

| ECOG performance status, No. (%) |

| 0, 58 (32.8%) |

| 1, 107 (60.4%) |

| 2, 12 (6.8%) |

| Co-morbidities, No. (%) |

| HTN, 41 (23.1%) |

| Type II Diabetes Mellitus, 10 (5.6%) |

| IHD, 3 (1.69%) |

| Hypothyroidism, 9 (5.06%) |

| Asthma/COPD, 15 (8.4%) |

| No comorbidities, 81 (45.7%) |

| Radiological response post chemotherapy (prior to PARPi initiation), No. (%) |

| Complete response, 39, (22%) |

| Partial response, 110, (62.1%) |

| Stable disease, 9, (5.08%) |

| Mixed response, 4 (2.25%) |

| No radiology imaging available, 15 (8.4%) |

| Chemotherapy regimen prior to PARPI, No. (%) |

| Platinum doublet chemotherapy, 144 (81.3%) |

| Platinum doublet + Bevacizumab, 2 (1.12%) |

| Platinum single agent, 31 (17.5%) |

| Subgroup | n | Median PFS (Months) | p-Value | Median OS (Months) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 vs. BRCA2 (olaparib, primary) | 10 vs. 12 | 29.0 vs. NR | 0.002 | 49.0 vs. NR | 0.163 |

| BRCA–wild-type (niraparib, primary) | 60 | 11.0 | – | 29.0 | – |

| Upfront vs. interval surgery | 14 vs. 62 | 37.0 vs. 19.0 | 0.49 | 53.0 vs. 40.0 | 0.50 |

| Niraparib vs. rucaparib (recurrent) | 35 vs. 34 | 10.0 vs. 9.0 | 0.59 | – | – |

| HRD vs. HRP (primary) | 20 vs. 19 | 21.0 vs. NR | 0.71 | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Ani, M.; Baraka, B.; Mathiyalagan, N.; Sarwar, M.A.; Segaran, A.; Abuzahra, W.; Radford, A.; Buxton, K.; Seneviratne, L.; Sundar, S.; et al. The Real-World Impact of PARP Inhibitor Maintenance Therapy in High Grade Serous Tubo-Ovarian and Peritoneal Cancers. Cancers 2025, 17, 3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213591

Al-Ani M, Baraka B, Mathiyalagan N, Sarwar MA, Segaran A, Abuzahra W, Radford A, Buxton K, Seneviratne L, Sundar S, et al. The Real-World Impact of PARP Inhibitor Maintenance Therapy in High Grade Serous Tubo-Ovarian and Peritoneal Cancers. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213591

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Ani, Maryam, Bahaaeldin Baraka, Navin Mathiyalagan, Muhammad Adeel Sarwar, Avinash Segaran, Wafaa Abuzahra, Alayna Radford, Kersty Buxton, Lalith Seneviratne, Santhanam Sundar, and et al. 2025. "The Real-World Impact of PARP Inhibitor Maintenance Therapy in High Grade Serous Tubo-Ovarian and Peritoneal Cancers" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213591

APA StyleAl-Ani, M., Baraka, B., Mathiyalagan, N., Sarwar, M. A., Segaran, A., Abuzahra, W., Radford, A., Buxton, K., Seneviratne, L., Sundar, S., Anand, A., Nunns, D., Williamson, K., Wormald, B., Gajjar, K., & Madhusudan, S. (2025). The Real-World Impact of PARP Inhibitor Maintenance Therapy in High Grade Serous Tubo-Ovarian and Peritoneal Cancers. Cancers, 17(21), 3591. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213591