Sugammadex Versus Neostigmine in Return to Intended Oncological Therapy After Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

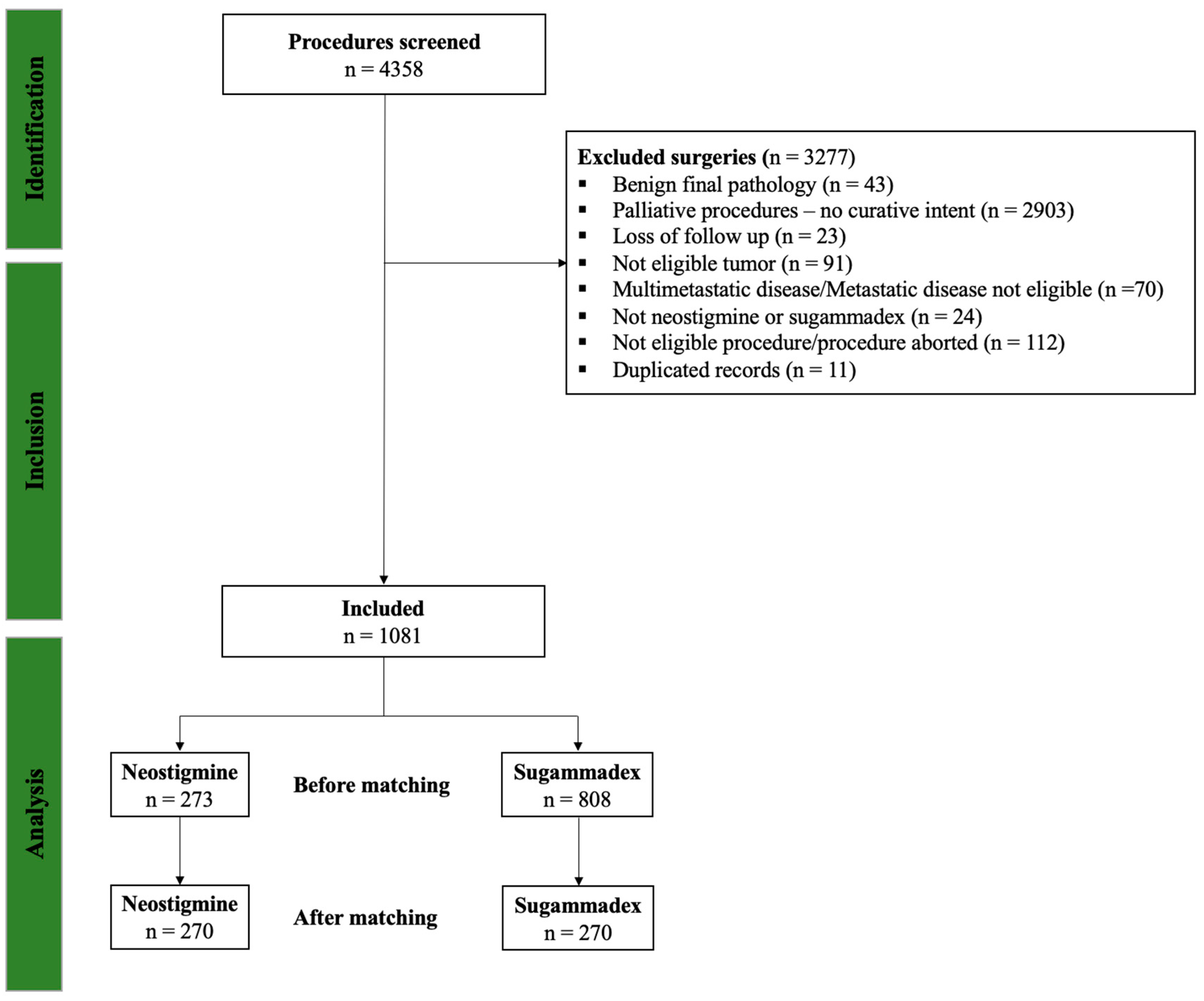

2.1. Patients

2.2. Variables and Definitions

2.3. Exposure

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Clinical Status

3.2. RIOT Outcomes

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burotto, M.; Wilkerson, J.; Stein, W.D.; Bates, S.E.; Fojo, T. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant cancer therapies: A historical review and a rational approach to understand outcomes. Semin. Oncol. 2019, 46, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohsiriwat, V. Enhanced recovery after surgery vs conventional care in emergency colorectal surgery. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 13950–13955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes-Mejia, N.A.; Lillemoe, H.A.; Cata, J.P. Return to Intended Oncological Therapy: State of the Art and Perspectives. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloia, T.A.; Zimmitti, G.; Conrad, C.; Gottumukalla, V.; Kopetz, S.; Vauthey, J.-N. Return to intended oncologic treatment (RIOT): A novel metric for evaluating the quality of oncosurgical therapy for malignancy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 110, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, D.T.; Buggy, D.J. Return to intended oncologic therapy: A potentially valuable endpoint for perioperative research in cancer patients? Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 124, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.K.; Teng, A.; Lee, D.Y.; Rose, K. Pulmonary complications after major abdominal surgery: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 198, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, S.C.; Hemmes, S.N.T.; Queiroz, V.N.F.; Neto, A.S.; Gregoretti, C.; Tschernko, E.; de Abreu, M.G.; Patroniti, N.; Schultz, M.J.; Mazzinari, G.; et al. Postoperative Pulmonary Complications in Conventional Laparoscopic vs Robot-Assisted Abdominal Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ri, M.; Nunobe, S.; Narita, T.; Seto, Y.; Kawazoe, Y.; Ohe, K.; Azuma, L.; Takeshita, N. Time-sequential prediction of postoperative complications after gastric cancer surgery using machine learning: A multicenter cohort study. Gastric Cancer 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Pace-Loscos, T.; Schiappa, R.; Delotte, J.; Barranger, E.; Delpech, Y.; Salucki, B.; Gauci, P.-A.; Gosset, M. Therapeutic impact of eras protocol implementation in cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2025, 313, 114622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solanki, S.L.; Sanapala, V.; Ambulkar, R.P.; Agarwal, V.; Saklani, A.P.; Maheshwari, A. A Prospective Observational Study on Compliance with Enhanced Recovery Pathways and Their Impact on Postoperative Outcomes Following Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2025, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin-Rojas, M.; Bolm, L.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Fong, Z.V.; Narayan, R.R.; Castillo, C.F.-D.; Qadan, M. Preoperative Biopsy Is Not Associated With Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Undergoing Upfront Resection. J. Surg. Res. 2025, 307, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Agarwal, V.; DeSouza, A.; Joshi, R.; Mali, M.; Panhale, K.; Salvi, O.K.; Ambulkar, R.; Shrikhande, S.; Saklani, A. Enhanced recovery pathway in open and minimally invasive colorectal cancer surgery: A prospective study on feasibility, compliance, and outcomes in a high-volume resource limited tertiary cancer center. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Han, S.-H.; Park, J.-W. Effects of neuromuscular block reversal with neostigmine/glycopyrrolate versus sugammadex on bowel motility recovery after laparoscopic colorectal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Anesthesia 2024, 98, 111588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghiri, S.; Prassas, D.; Krieg, S.; Knoefel, W.T.; Krieg, A. The Postoperative Effect of Sugammadex versus Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors in Colorectal Surgery: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-M.; Yu, H.; Zuo, Y.-D.; Liang, P. Postoperative pulmonary complications after sugammadex reversal of neuromuscular blockade: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togioka, B.M.; Rakshe, S.K.; Ye, S.; Tekkali, P.; Tsikitis, V.L.; Fang, S.H.; Herzig, D.O.; Lu, K.C.; Aziz, M.F. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Sugammadex versus Neostigmine for Reversal of Rocuronium on Gastric Emptying in Adults Undergoing Elective Colorectal Surgery. Anesthesia Analg. 2025, 141, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes-Mejía, N.; Guerra-Londono, J.J.; Feng, L.; Gloria-Escobar, J.M.; Lillemoe, H.A.; Ovsak, G.; Cata, J.P. The impact of sugammadex versus neostigmine reversal on return to intended oncological therapy-related outcomes after breast cancer surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Perioper. Med. 2025, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual and the Future of TNM. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 1471–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratios. Stat. Med. 2006, 26, 3078–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Londono, C.E.; Schreck, A.; Muthukumar, A.; Guerra-Londono, J.J. Return to intended oncologic treatment: Definitions, perioperative prognostic factors, and interventions. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2025, 39, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckman, M.; Gupta, P.; Panchumarthi, V.; Bloomfield, G.; Namgoong, J.; Nigam, A.; Fishbein, T.; Radkani, P.; Winslow, E. Return to intended oncologic therapies in pancreatectomy patients: Surgery first approach. HPB 2024, 26, S702–S703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointer, D.T.; Felder, S.I.; Powers, B.D.; Dessureault, S.; Sanchez, J.A.; Imanirad, I.; Sahin, I.; Xie, H.; Naffouje, S.A. Return to intended oncologic therapy after colectomy for stage III colon adenocarcinoma: Does surgical approach matter? Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 1760–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, A.; Mavani, P.T.; Sok, C.; Goyal, S.; Concors, S.; Mason, M.C.; Winer, J.H.; Russell, M.C.; Cardona, K.; Lin, E.; et al. Effect of Minimally Invasive Gastrectomy on Return to Intended Oncologic Therapy for Gastric Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 32, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.F.K.P.; de Castria, T.B.; Pereira, M.A.; Dias, A.R.; Antonacio, F.F.; Zilberstein, B.; Hoff, P.M.G.; Ribeiro, U.; Cecconello, I. Return to Intended Oncologic Treatment (RIOT) in Resected Gastric Cancer Patients. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2019, 24, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggett, S.; Chahal, R.; Griffiths, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, D.; Williams, Z.; Riedel, B.; Bowyer, A.; Royse, A.; Royse, C. A randomised controlled trial comparing deep neuromuscular blockade reversed with sugammadex with moderate neuromuscular block reversed with neostigmine. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.; Abdulrahem, A.M.; Alqannas, M.; AlHabes, H.; Alyami, A.; Alshammari, S.; Guiral, D.C.; Alzamanan, M.; Alzahrani, N.; Bin Traiki, T. Robotic and Laparoscopic Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy, Multicenter Study From Saudi Arabia. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 130, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkow, R.P.; Bentrem, D.J.; Mulcahy, M.F.; Chung, J.W.; Abbott, D.E.; Kmiecik, T.E.; Stewart, A.K.M.; Winchester, D.P.; Ko, C.Y.M.; Bilimoria, K.Y. Effect of Postoperative Complications on Adjuvant Chemotherapy Use for Stage III Colon Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, J.J.; Raphael, M.J.; Mackillop, W.J.; Kong, W.; King, W.D.; Booth, C.M. Association Between Time to Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Survival in Colorectal Cancer. JAMA 2011, 305, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselgren, E.; Groes-Kofoed, N.; Falconer, H.; Björne, H.; Zach, D.; Hunde, D.; Johansson, H.; Asp, M.; Kannisto, P.; Gupta, A.; et al. Effect of intraperitoneal ropivacaine during and after cytoreductive surgery on time-interval to adjuvant chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer: A randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 134, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Unmatched Cohort | Matched Cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Neostigmine n = 273 | Sugammadex n = 808 | Overall n = 1081 | p-value | Neostigmine n = 270 | Sugammadex n = 270 | Standardized Difference in % |

| Age at surgery, in years | 59.5 (49.1, 68.1) | 60.9 (52.1, 69.7) | 60.4 (51.3, 69.1) | 0.021 | 57.97 (17.7) | 58.23 (12.82) | 1.97 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.776 | ||||||

| Female | 107 (39.2%) | 325 (40.2%) | 432 (40.0%) | ||||

| Male | 166 (60.8%) | 483 (59.8%) | 649 (60.0%) | ||||

| BMI, in kg/m2 | 27.5 (24.4, 31.7) | 27.8 (25.1, 31.4) | 27.7 (24.8, 31.5) | 0.429 | |||

| Racial/Ethnic distribution, n (%) | 0.006 | 5.23 (1.25) | 5.22 (1.27) | 0.29 | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 3 (0.3%) | ||||

| Asian | 16 (5.9%) | 35 (4.4%) | 51 (4.8%) | ||||

| Black or African American | 10 (3.7%) | 52 (6.5%) | 62 (5.8%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 53 (19.6%) | 91 (11.4%) | 144 (13.4%) | ||||

| Other | 6 (2.2%) | 14 (1.8%) | 20 (1.9%) | ||||

| White or Caucasian | 185 (68.3%) | 606 (75.8%) | 791 (73.9%) | ||||

| Missing | 2 (0.73%) | 8 (0.99%) | 10 (0.93%) | ||||

| ASA class, n (%) | 0.078 | 0.92 (0.92) | 0.91 (0.28) | 1.34 | |||

| 1–2 | 23 (8.4%) | 43 (5.3%) | 66 (6.1%) | ||||

| 3–4 | 250 (91.6%) | 765 (94.7%) | 1015 (93.9%) | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 0.530 | |||

| Type of cancer, n (%) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 19 (7.0%) | 47 (5.8%) | 66 (6.1%) | ||||

| Colorectal | 90 (33.0%) | 299 (37.0%) | 389 (36.0%) | ||||

| Esophageal | 20 (7.3%) | 93 (11.5%) | 113 (10.5%) | ||||

| Gastric | 33 (12.1%) | 51 (6.3%) | 84 (7.8%) | ||||

| Metastatic to the Live º | 73 (26.7%) | 196 (24.3%) | 269 (24.9%) | ||||

| NET | 12 (4.4%) | 27 (3.3%) | 39 (3.6%) | ||||

| Pancreatic | 26 (9.5%) | 95 (11.8%) | 121 (11.2%) | ||||

| Cancer staging, n (%) | 0.661 | ||||||

| 0ª | 8 (2.9%) | 33 (4.1%) | 41 (3.8%) | ||||

| I | 42 (15.4%) | 150 (18.6%) | 192 (17.8%) | ||||

| II | 81 (29.7%) | 233 (28.8%) | 314 (29.0%) | ||||

| III | 69 (25.3%) | 196 (24.3%) | 265 (24.5%) | ||||

| IV | 73 (26.7%) | 196 (24.3%) | 269 (24.9%) | ||||

| NACT within 90 days, n (%) | 137 (50.2%) | 403 (49.9%) | 540 (50.0%) | 0.944 | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 127 (46.5%) | 388 (48.0%) | 515 (47.6%) | 0.675 | |||

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy, n (%) | 70 (25.6%) | 190 (23.5%) | 260 (24.1%) | 0.512 | |||

| Before Propensity Score Matching | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIOT 90 days | RIOT 180 days | |||||||

| Effect | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI for OR | p-value | ||

| CCI > 5 vs. ≤5 | 3.29 | 1.63 | 6.66 | 0.0009 | 2.09 | 1.17 | 3.75 | 0.012 |

| Neostigmine vs. Sugammadex | 1.91 | 1.01 | 3.62 | 0.046 | 1.8 | 1.01 | 3.22 | 0.045 |

| Anesthesia duration every 1 min | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.006 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.056 |

| After propensity score matching | ||||||||

| Effect | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI for OR | p-value | ||

| CCI > 5 vs. ≤5 | 2.8 | 1.19 | 6.59 | 0.018 | 1.89 | 0.91 | 3.93 | 0.085 |

| Neostigmine vs. Sugammadex | 1.66 | 0.74 | 3.74 | 0.217 | 1.33 | 0.65 | 2.73 | 0.427 |

| Anesthesia duration every 1 min | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.025 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.122 |

| Characteristic | Unmatched Cohort | Matched Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neostigmine n = 273 | Sugammadex n = 808 | p-Value | Neostigmine n = 270 | Sugammadex n = 270 | p-Value | |

| Any RIOT 90 days, n (%) | 0.324 | 0.298 | ||||

| No | 146 (53.5) | 461 (57.1) | 145 (53.7) | 158 (58.5) | ||

| Yes | 127 (46.5) | 347 (42.9) | 125 (46.3) | 112 (41.5) | ||

| Any RIOT 180 days, n (%) | 0.294 | 0.228 | ||||

| No | 127 (46.5) | 406 (50.2) | 126 (46.7) | 141 (52.2) | ||

| Yes | 146 (53.5) | 402 (49.8) | 144 (53.3) | 129 (47.8) | ||

| Chemotherapy RIOT 90 days, n (%) | 0.944 | 0.725 | ||||

| No | 159 (58.2) | 473 (58.5) | 158 (58.5) | 163 (60.4) | ||

| Yes | 114 (41.8) | 335 (41.5) | 112 (41.5) | 107 (39.6) | ||

| Chemotherapy RIOT 180 days, n (%) | 0.889 | 0.546 | ||||

| No | 139 (50.9) | 417 (51.6) | 138 (51.1) | 146 (54.1) | ||

| Yes | 134 (49.1) | 391 (48.4) | 132 (48.9) | 124 (45.9) | ||

| Chemotherapy time-to-RIOT (days) | 49 (34, 69) | 46 (34.7, 73) | 0.706 | 49 (34.0, 69.6) | 46.5 (35.4, 85) | 0.984 |

| Radiotherapy RIOT 90 days, n (%) | 0.032 | 0.235 | ||||

| No | 256 (93.8) | 782 (96.8) | 253 (93.7) | 260 (96.3) | ||

| Yes | 17 (6.2) | 26 (3.2) | 17 (6.3) | 10 (3.7) | ||

| Radiotherapy RIOT 180 days, n (%) | 0.036 | 0.472 | ||||

| No | 253 (92.7) | 775 (95.9) | 251 (93) | 256 (94.8) | ||

| Yes | 20 (7.3) | 33 (4.1) | 19 (7) | 14 (5.2) | ||

| Radiotherapy time-to-RIOT, in days | 49.5 (41, 147.5) | 54 (41, 111) | 0.920 | 49 (40, 131) | 42 (29, 130) | 0.731 |

| Variables | Unmatched Cohort | Matched Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neostigmine n = 273 | Sugammadex n = 808 | p-Value | Neostigmine n = 270 | Sugammadex n = 270 | p-Value | |

| Length of stay | 5.5 (4.3, 8.3) | 5.4 (4.1, 7.5) | 0.115 | 5.5 (4.3, 8.3) | 5.3 (3.5, 7.5) | 0.082 |

| 30-day postoperative readmission, n (%) | 31 (11.4) | 87 (10.8) | 0.822 | 31 (11.5%) | 29 (10.7%) | 0.891 |

| 90-day postoperative readmission, n (%) | 43 (15.8) | 137 (17.) | 0.707 | 43 (15.9%) | 41 (15.2%) | 0.905 |

| 180-day postoperative readmission, n (%) | 62 (22.7) | 196 (24.3) | 0.623 | 62 (23.0%) | 67 (24.8%) | 0.686 |

| Day of first readmission | 30 (14.0, 137) | 44 (14, 105) | 0.774 | 30.0 (14.0, 137.0) | 44.0 (14.0, 125.0) | 0.867 |

| 180-Day ICU Admission, n (%) | 10 (3.7) | 21 (2.6) | 0.401 | 10 (3.7%) | 7 (2.6%) | 0.623 |

| Days from surgery to ICU admission | 8 (5, 15) | 3 (1, 14) | 0.289 | 8.0 (5.0, 15.0) | 5.0 (0.0, 65.0) | 0.769 |

| ICU length of stay, in nights | 2.4 (1.1, 6.4) | 2.1 (1, 4) | 0.410 | 2.4 (1.1, 6.4) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.9) | 0.261 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cortes-Mejia, N.A.; Guerra-Londono, J.J.; Islam, T.; Lillemoe, H.A.; Ovsak, G.; Feng, L.; Cata, J.P. Sugammadex Versus Neostigmine in Return to Intended Oncological Therapy After Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213553

Cortes-Mejia NA, Guerra-Londono JJ, Islam T, Lillemoe HA, Ovsak G, Feng L, Cata JP. Sugammadex Versus Neostigmine in Return to Intended Oncological Therapy After Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213553

Chicago/Turabian StyleCortes-Mejia, Nicolas A., Juan J. Guerra-Londono, Tarikul Islam, Heather A. Lillemoe, Gavin Ovsak, Lei Feng, and Juan P. Cata. 2025. "Sugammadex Versus Neostigmine in Return to Intended Oncological Therapy After Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Study" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213553

APA StyleCortes-Mejia, N. A., Guerra-Londono, J. J., Islam, T., Lillemoe, H. A., Ovsak, G., Feng, L., & Cata, J. P. (2025). Sugammadex Versus Neostigmine in Return to Intended Oncological Therapy After Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Cancers, 17(21), 3553. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213553