Evaluating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA for the Early Detection of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval and Study Design

2.2. Data Collection and Annotation

2.3. TTMV-HPV DNA Testing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

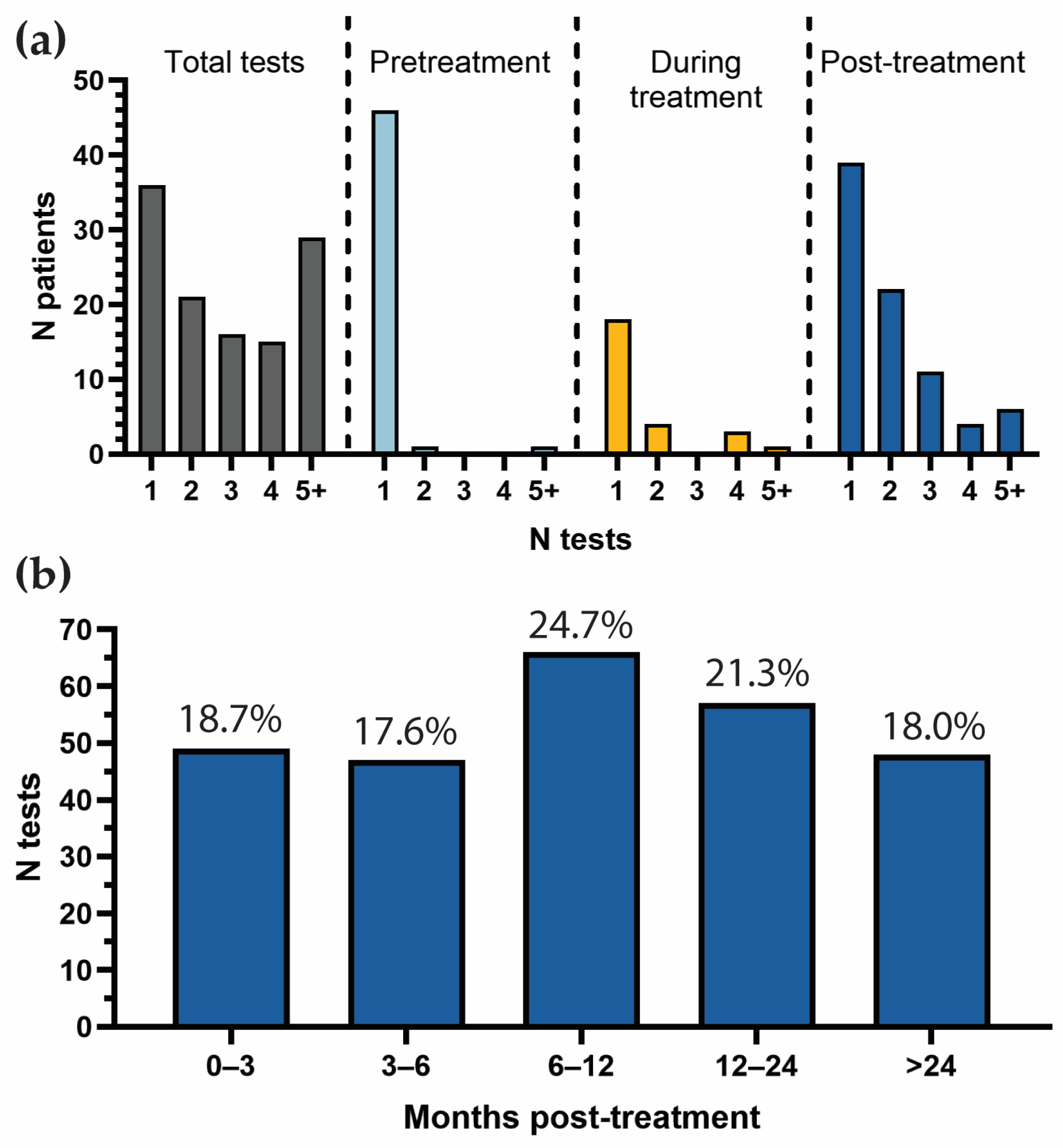

3.2. Patterns and Frequency of TTMV-HPV DNA Testing

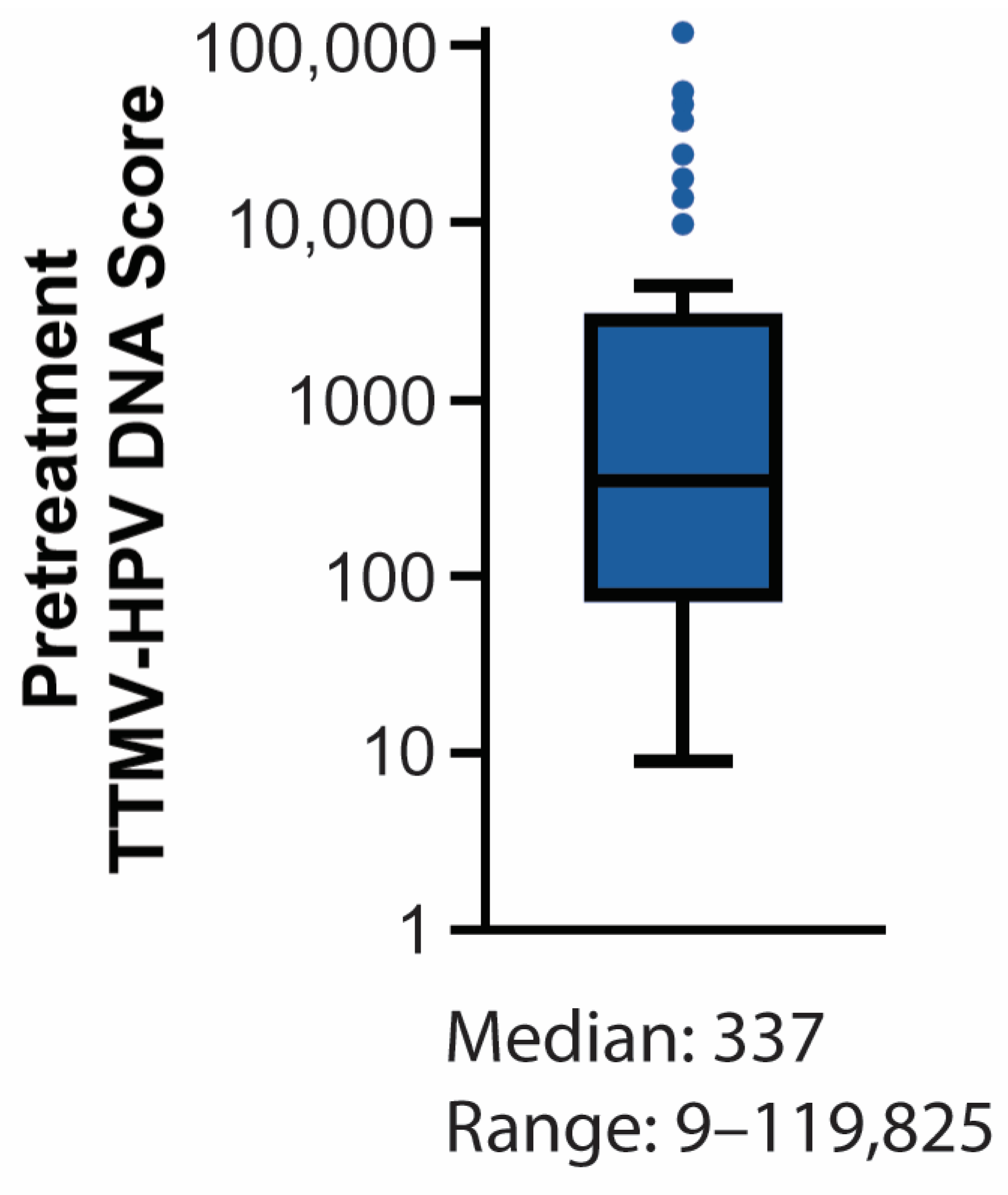

3.3. Baseline TTMV-HPV DNA Detectability

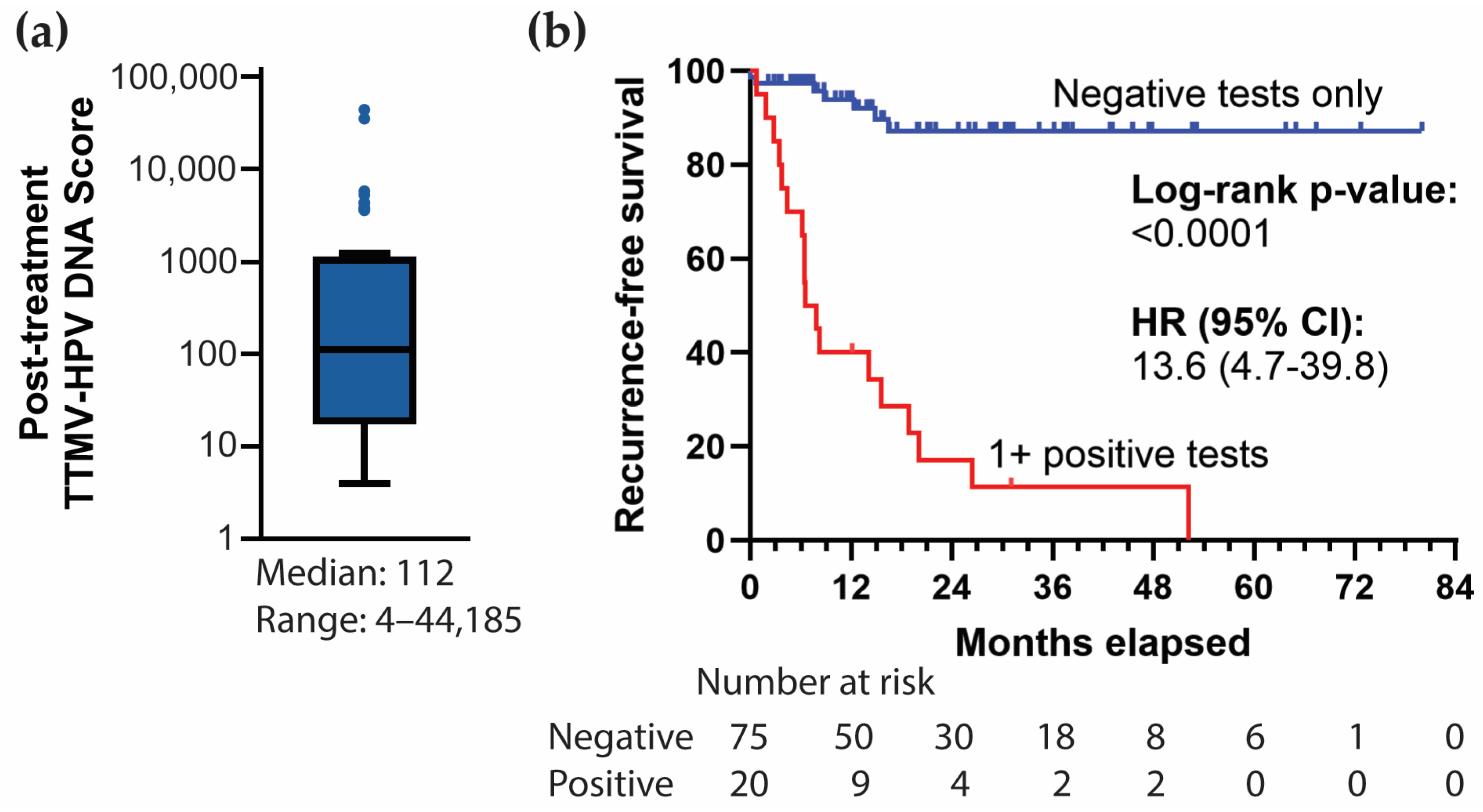

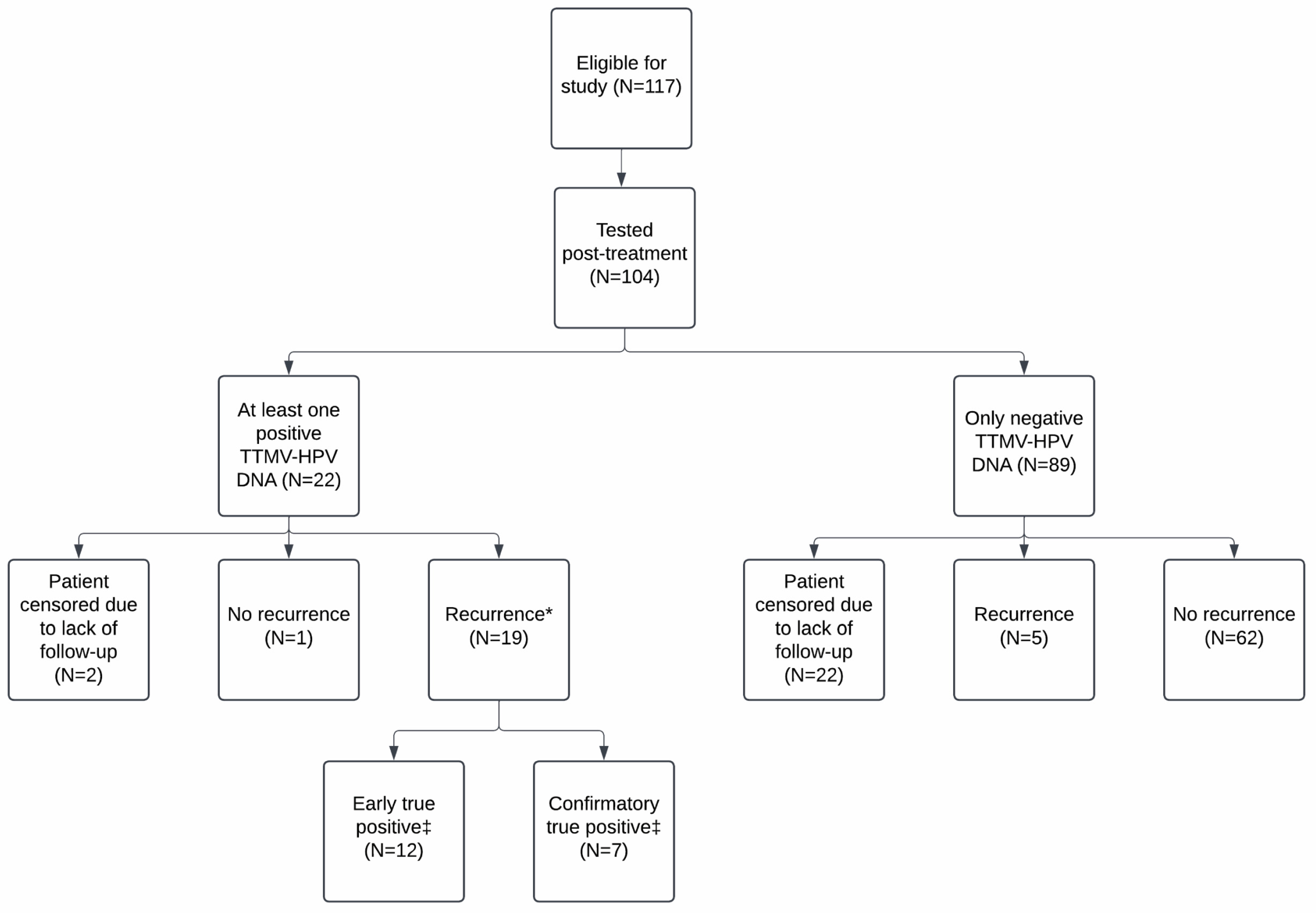

3.4. Post-Treatment TTMV-HPV DNA Performance Metrics

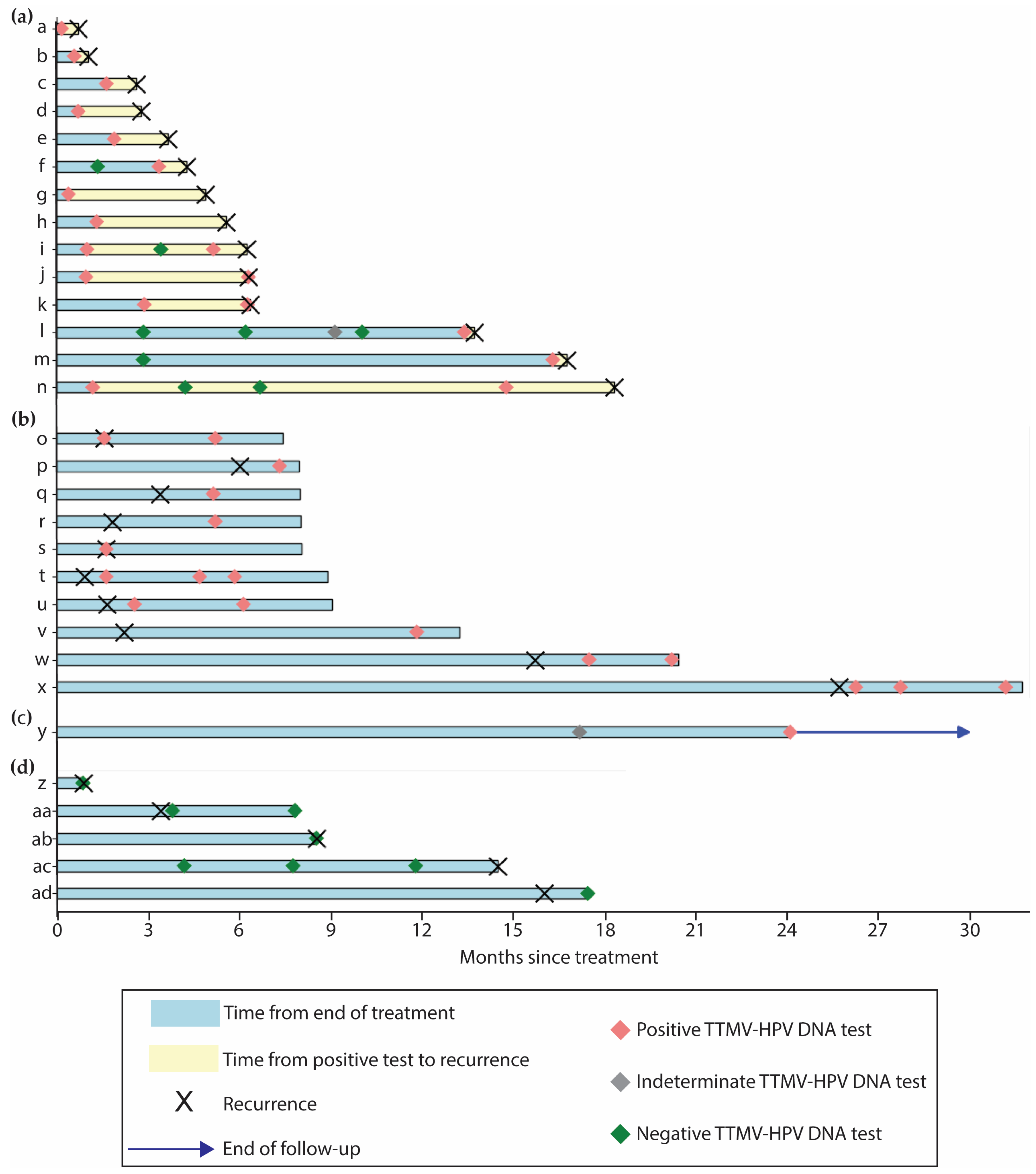

3.5. Correlation with Clinical Recurrence

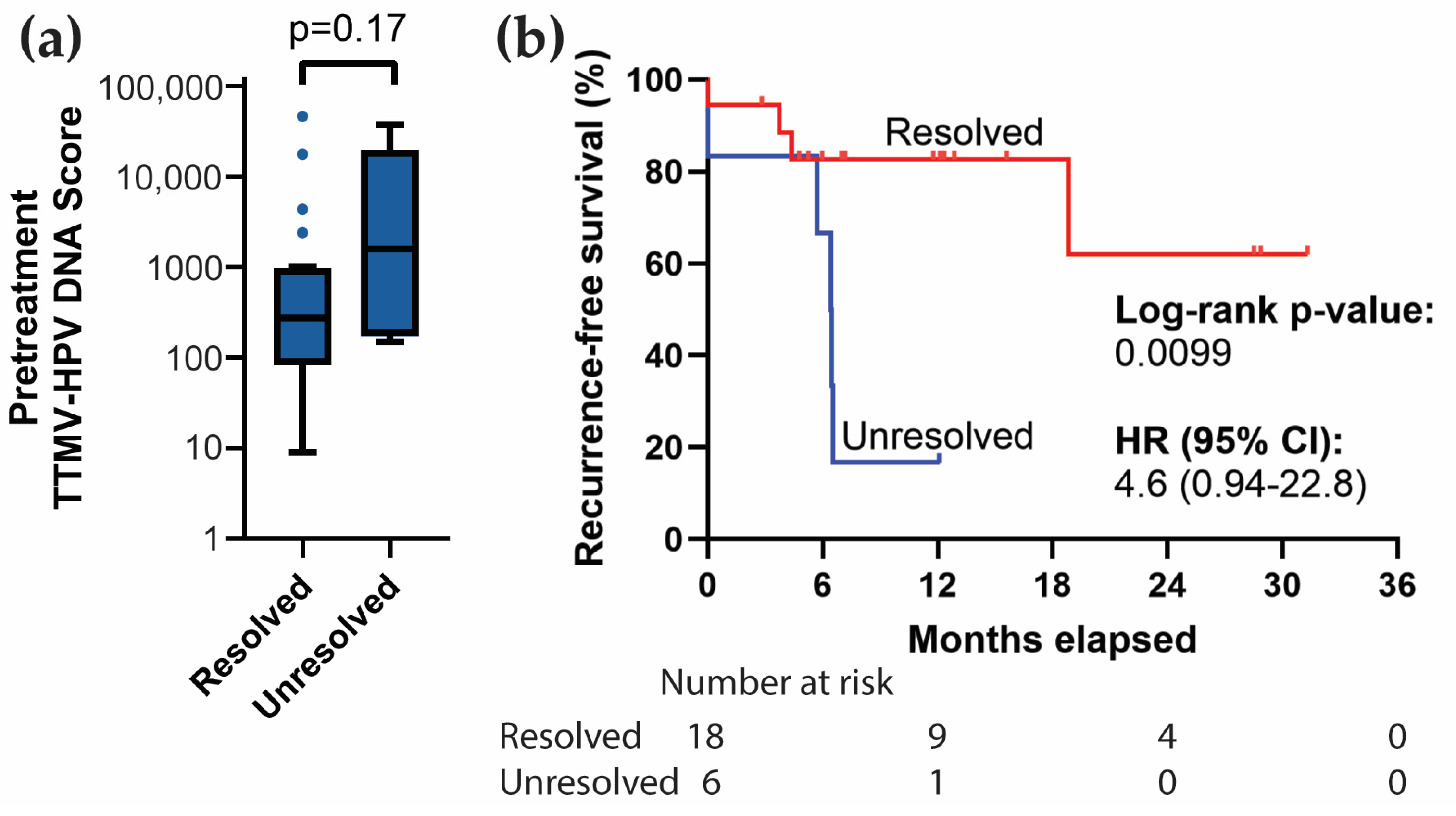

3.6. Resolution of Positive Baseline TTMV-HPV DNA

3.7. Resolution of Clinically Indeterminate Findings (CIFs)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deshmukh, A.A.; Suk, R.; Shiels, M.S.; Damgacioglu, H.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Stier, E.A.; Nyitray, A.G.; Chiao, E.Y.; Nemutlu, G.S.; Chhatwal, J.; et al. Incidence Trends and Burden of Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers Among Women in the United States, 2001–2017. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh, A.A.; Suk, R.; Shiels, M.S.; Sonawane, K.; Nyitray, A.G.; Liu, Y.; Gaisa, M.M.; Palefsky, J.M.; Sigel, K. Recent Trends in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 2001–2015. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2020, 112, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Franceschi, S.; Clifford, G.M. Human Papillomavirus Types from Infection to Cancer in the Anus, According to Sex and HIV Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Guren, M.G.; Khan, K.; Brown, G.; Renehan, A.G.; Steigen, S.E.; Deutsch, E.; Martinelli, E.; Arnold, D. Anal Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up☆. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Al-Hawary, M.M.; Azad, N.; Chen, Y.-J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; et al. Anal Carcinoma, Version 2.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 653–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, C.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cho, M.; Dorth, J.A.; Rajdev, L.N.; Horowitz, D.P.; Gollub, M.J.; Jácome, A.A.; Lockney, N.A.; Muldoon, R.L.; et al. Anal Cancer: Emerging Standards in a Rare Disease. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2774–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, J.B.; Brister, K.A. Management of Recurrent Anal Cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. 2025, 34, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, L.; Hartzell, M.; Parikh, A.R.; Strickland, M.R.; Klempner, S.; Malla, M. Recent Advances in the Management of Anal Cancer. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnell, G.M.; Schechter, M.S. Anal Cancer Screening and Prevention—A New Era, Limited by Access to High-Resolution Anoscopy. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e240019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rim, S.H.; Saraiya, M.; Beer, L.; Tie, Y.; Yuan, X.; Weiser, J. Access to High-Resolution Anoscopy Among Persons with HIV and Abnormal Anal Cytology Results. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e240068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rim, S.H.; Beer, L.; Saraiya, M.; Tie, Y.; Yuan, X.; Weiser, J. Prevalence of Anal Cytology Screening among Persons with HIV and Lack of Access to High-Resolution Anoscopy at HIV Care Facilities. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damgacioglu, H.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Ortiz, A.P.; Wu, C.-F.; Shahmoradi, Z.; Shyu, S.S.; Li, R.; Nyitray, A.G.; Sigel, K.; Clifford, G.M.; et al. State Variation in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus Incidence and Mortality, and Association With HIV/AIDS and Smoking in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard-Tessier, A.; Jeannot, E.; Guenat, D.; Debernardi, A.; Michel, M.; Proudhon, C.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Bièche, I.; Pierga, J.-Y.; Buecher, B.; et al. Clinical Validity of HPV Circulating Tumor DNA in Advanced Anal Carcinoma: An Ancillary Study to the Epitopes-HPV02 Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabel, L.; Jeannot, E.; Bieche, I.; Vacher, S.; Callens, C.; Bazire, L.; Morel, A.; Bernard-Tessier, A.; Chemlali, W.; Schnitzler, A.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Residual HPV ctDNA Detection after Chemoradiotherapy for Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 5767–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damerla, R.R.; Lee, N.Y.; You, D.; Soni, R.; Shah, R.; Reyngold, M.; Katabi, N.; Wu, V.; McBride, S.M.; Tsai, C.J.; et al. Detection of Early Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers by Liquid Biopsy. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2019, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannot, E.; Becette, V.; Campitelli, M.; Calméjane, M.; Lappartient, E.; Ruff, E.; Saada, S.; Holmes, A.; Bellet, D.; Sastre-Garau, X. Circulating Human Papillomavirus DNA Detected Using Droplet Digital PCR in the Serum of Patients Diagnosed with Early Stage Human Papillomavirus-associated Invasive Carcinoma. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2016, 2, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Cutts, R.J.; White, I.; Augustin, Y.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Fenwick, K.; Matthews, N.; Turner, N.C.; Harrington, K.; Gilbert, D.C.; et al. Next Generation Sequencing Assay for Detection of Circulating HPV DNA (cHPV-DNA) in Patients Undergoing Radical (Chemo)Radiotherapy in Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ASCC). Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefèvre, A.C.; Pallisgaard, N.; Kronborg, C.; Wind, K.L.; Krag, S.R.P.; Spindler, K.-L.G. The Clinical Value of Measuring Circulating HPV DNA during Chemo-Radiotherapy in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus. Cancers 2021, 13, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, A.C.; Kronborg, C.; Sørensen, B.S.; Krag, S.R.P.; Serup-Hansen, E.; Spindler, K.-L.G. Measurement of Circulating Free DNA in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anus and Relation to Risk Factors and Recurrence. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2020, 150, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, V.K.; Xiao, W.; Holliday, E.B.; Lin, K.; Huey, R.W.; Noticewala, S.S.; Ludmir, E.B.; Bent, A.H.; Higbie, V.; Koay, E.J.; et al. Time Dependency for HPV ctDNA Detection as a Prognostic Biomarker for Anal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chera, B.S.; Kumar, S.; Beaty, B.T.; Marron, D.; Jefferys, S.; Green, R.; Goldman, E.C.; Amdur, R.; Sheets, N.; Dagan, R.; et al. Rapid Clearance Profile of Plasma Circulating Tumor HPV Type 16 DNA during Chemoradiotherapy Correlates with Disease Control in HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4682–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, B.M.; Hanna, G.J.; Posner, M.R.; Genden, E.M.; Lautersztain, J.; Naber, S.P.; Del Vecchio Fitz, C.; Kuperwasser, C. Detection of Occult Recurrence Using Circulating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral HPV DNA among Patients Treated for HPV-Driven Oropharyngeal Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4292–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, G.J.; Roof, S.A.; Jabalee, J.; Rettig, E.M.; Ferrandino, R.; Chen, S.; Posner, M.R.; Misiukiewicz, K.J.; Genden, E.M.; Chai, R.L.; et al. Negative Predictive Value of Circulating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA for HPV-Driven Oropharyngeal Cancer Surveillance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 4306–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roof, S.A.; Jabalee, J.; Rettig, E.M.; Chennareddy, S.; Ferrandino, R.M.; Chen, S.; Posner, M.R.; Genden, E.M.; Chai, R.L.; Sims, J.; et al. Utility of TTMV-HPV DNA in Resolving Indeterminate Findings during Oropharyngeal Cancer Surveillance. Oral Oncol. 2024, 155, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunning, A.; Kumar, S.; Williams, C.K.; Berger, B.M.; Naber, S.P.; Gupta, P.B.; Fitz, C.D.V.; Kuperwasser, C. Analytical Validation of NavDx, a cfDNA-Based Fragmentomic Profiling Assay for HPV-Driven Cancers. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Edge, S.B., Greene, F.L., Byrd, D.R., Brookland, R.K., Washington, M.K., Gershenwald, J.E., Compton, C.C., Eds.; Springer Nature: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-40617-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ghodraty Jabloo, V.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Fitch, M.; Tourangeau, A.E.; Ayala, A.P.; Puts, M.T.E. Antecedents and Outcomes of Uncertainty in Older Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2017, 44, E152–E167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Santacroce, S.J.; Chen, D.-G.; Song, L. Illness Uncertainty, Coping, and Quality of Life among Patients with Prostate Cancer. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.J.; Hillner, B.E. Bending the Cost Curve in Cancer Care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2060–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallus, R.; Nauta, I.H.; Marklund, L.; Rizzo, D.; Crescio, C.; Mureddu, L.; Tropiano, P.; Delogu, G.; Bussu, F. Accuracy of P16 IHC in Classifying HPV-Driven OPSCC in Different Populations. Cancers 2023, 15, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemany, L.; Saunier, M.; Alvarado-Cabrero, I.; Quirós, B.; Salmeron, J.; Shin, H.-R.; Pirog, E.C.; Guimerà, N.; Hernandez-Suarez, G.; Felix, A.; et al. Human Papillomavirus DNA Prevalence and Type Distribution in Anal Carcinomas Worldwide. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serup-Hansen, E.; Linnemann, D.; Skovrider-Ruminski, W.; Høgdall, E.; Geertsen, P.F.; Havsteen, H. Human Papillomavirus Genotyping and P16 Expression as Prognostic Factors for Patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer Stages I to III Carcinoma of the Anal Canal. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n = 117 (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 63 (36–91) |

| Biological sex | |

| Female | 85 (72.6) |

| Male | 32 (27.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| White | 85 (72.6) |

| Black or African American | 12 (10.3) |

| Other | 15 (12.8) |

| Preferred not to answer | 5 (4.3) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 59 (50.4) |

| Former (≥10 pack years) | 32 (27.4) |

| Current | 25 (21.4) |

| HIV status | |

| Negative | 93 (79.5) |

| Positive | 14 (12.0) |

| Unknown | 10 (8.5) |

| Transplant status | |

| Not a transplant patient | 114 (97.4) |

| Transplant patient | 2 (1.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.9) |

| Site of primary disease | |

| Anal canal, no pelvic involvement | 74 (63.2) |

| Anal canal with pelvic involvement A | 39 (33.3) |

| Anal/perianal skin | 3 (2.6) |

| Rectum | 1 (0.9) |

| HPV reference testing method B | |

| p16 (by IHC) only | 84 (71.8) |

| p16 IHC and HPV PCR or ISH | 5 (4.3) |

| HPV PCR or ISH only | 4 (3.4) |

| TTMV-HPV DNA (FFPE tissue) | 9 (7.7) |

| Unreported methodology | 15 (12.8) |

| HPV subtype C | |

| 16 | 74 (92.5) |

| 16/18 | 1 (0.9) |

| 18 | 3 (2.6) |

| 33 | 2 (1.7) |

| Initial primary tumor staging D | |

| T0 | 1 (0.85) |

| T1 | 19 (16.2) |

| T2 | 44 (37.6) |

| T3 | 32 (27.4) |

| T4 | 21 (17.9) |

| Nodal status at baseline D | |

| N0 | 44 (37.6) |

| N1 | 73 (62.4) |

| Distant metastasis at baseline D | |

| M0 | 110 (94.0) |

| M1 | 7 (6.0) |

| Cancer stage | |

| I | 12 (10.3) |

| II | 30 (25.6) |

| III | 68 (58.1) |

| IV | 7 (6.0) |

| Initial treatment modality | |

| CRT | 106 (90.6) |

| Radiation | 4 (3.4) |

| Surgery, CRT | 3 (2.6) |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (1.7) |

| Surgery | 2 (1.7) |

| Cohort | True Positives | False Negatives | Sensitivity | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per-patient | 41 | 7 | 85.4 | 75.4–95.4 |

| Per-Test Accuracy Measures | |||

| Disease “+” | Disease “−” | Predictive value A | |

| Test positive | 41 | 1 | PPV = 97.6% (93.0–100) |

| Test negative | 7 | 134 | NPV = 95.0% (91.5–98.6) |

| Sensitivity and specificity | Sens. = 85.4% (75.4–95.4) | Spec. = 99.3% (97.8–100) | |

| Per-Patient Accuracy Measures | |||

| Test positive | 24 | 1 | PPV = 96.0% (88.3–100) |

| Test negative | 5 A,B | 62 | NPV = 92.5% (86.2–98.8) |

| Sensitivity and specificity | Sens. = 82.8% (69.0–96.5) | Spec. = 98.4% (95.3–100) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabarriti, R.; Lloyd, S.; Jabalee, J.; Del Vecchio Fitz, C.; Tao, R.; Slater, T.; Jacobs, C.; Inocencio, S.; Rutenberg, M.; Matthiesen, C.; et al. Evaluating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA for the Early Detection of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence. Cancers 2025, 17, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020174

Kabarriti R, Lloyd S, Jabalee J, Del Vecchio Fitz C, Tao R, Slater T, Jacobs C, Inocencio S, Rutenberg M, Matthiesen C, et al. Evaluating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA for the Early Detection of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence. Cancers. 2025; 17(2):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020174

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabarriti, Rafi, Shane Lloyd, James Jabalee, Catherine Del Vecchio Fitz, Randa Tao, Tyler Slater, Corbin Jacobs, Sean Inocencio, Michael Rutenberg, Chance Matthiesen, and et al. 2025. "Evaluating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA for the Early Detection of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence" Cancers 17, no. 2: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020174

APA StyleKabarriti, R., Lloyd, S., Jabalee, J., Del Vecchio Fitz, C., Tao, R., Slater, T., Jacobs, C., Inocencio, S., Rutenberg, M., Matthiesen, C., Neff, K., Liu, G.-F., Juarez, T. M., & Liauw, S. L. (2025). Evaluating Tumor Tissue Modified Viral (TTMV)-HPV DNA for the Early Detection of Anal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence. Cancers, 17(2), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17020174