The Role of Nutrition in HPV Infection and Cervical Cancer Development: A Review of Protective Dietary Factors

Simple Summary

Abstract

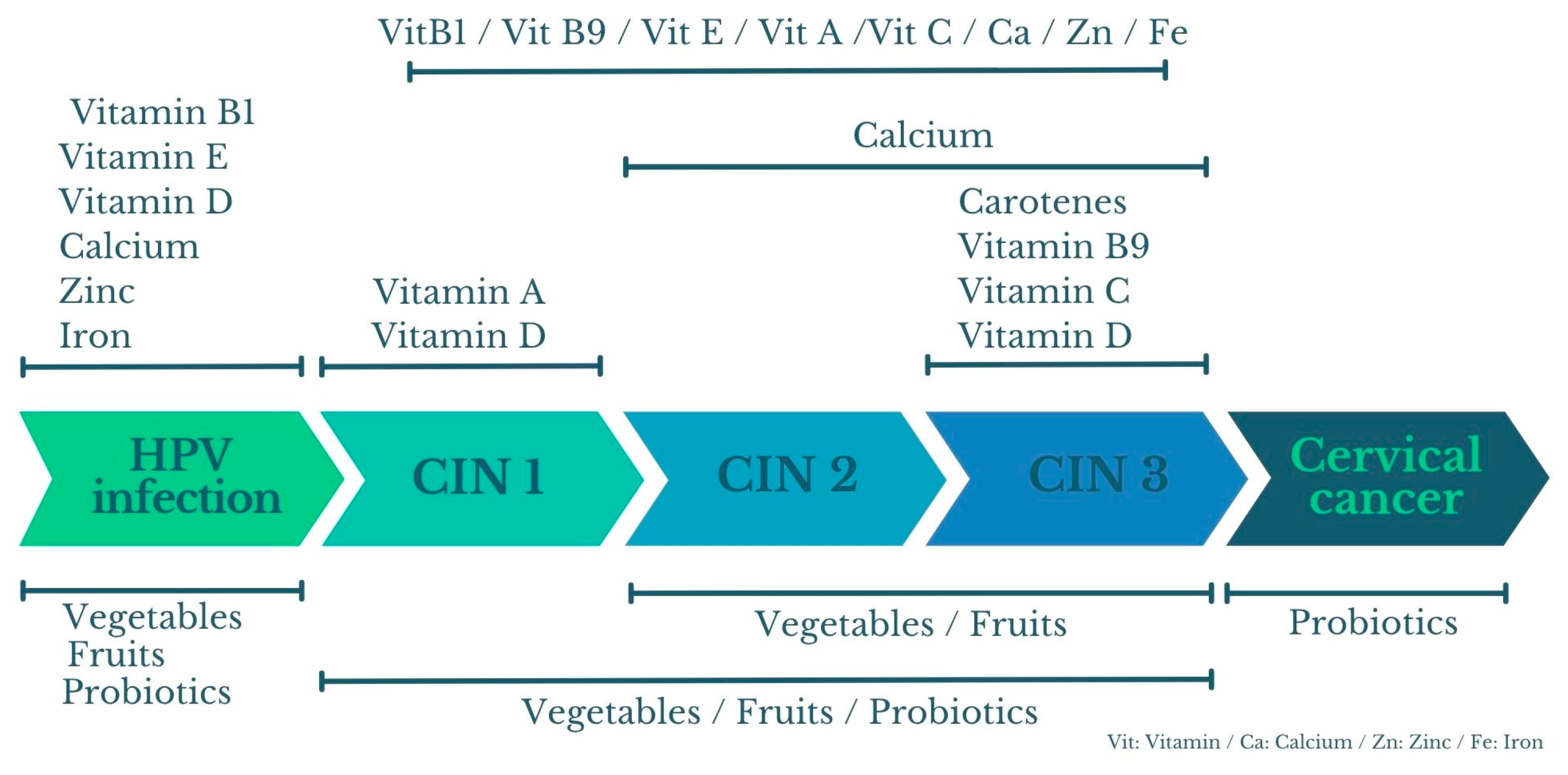

1. Introduction

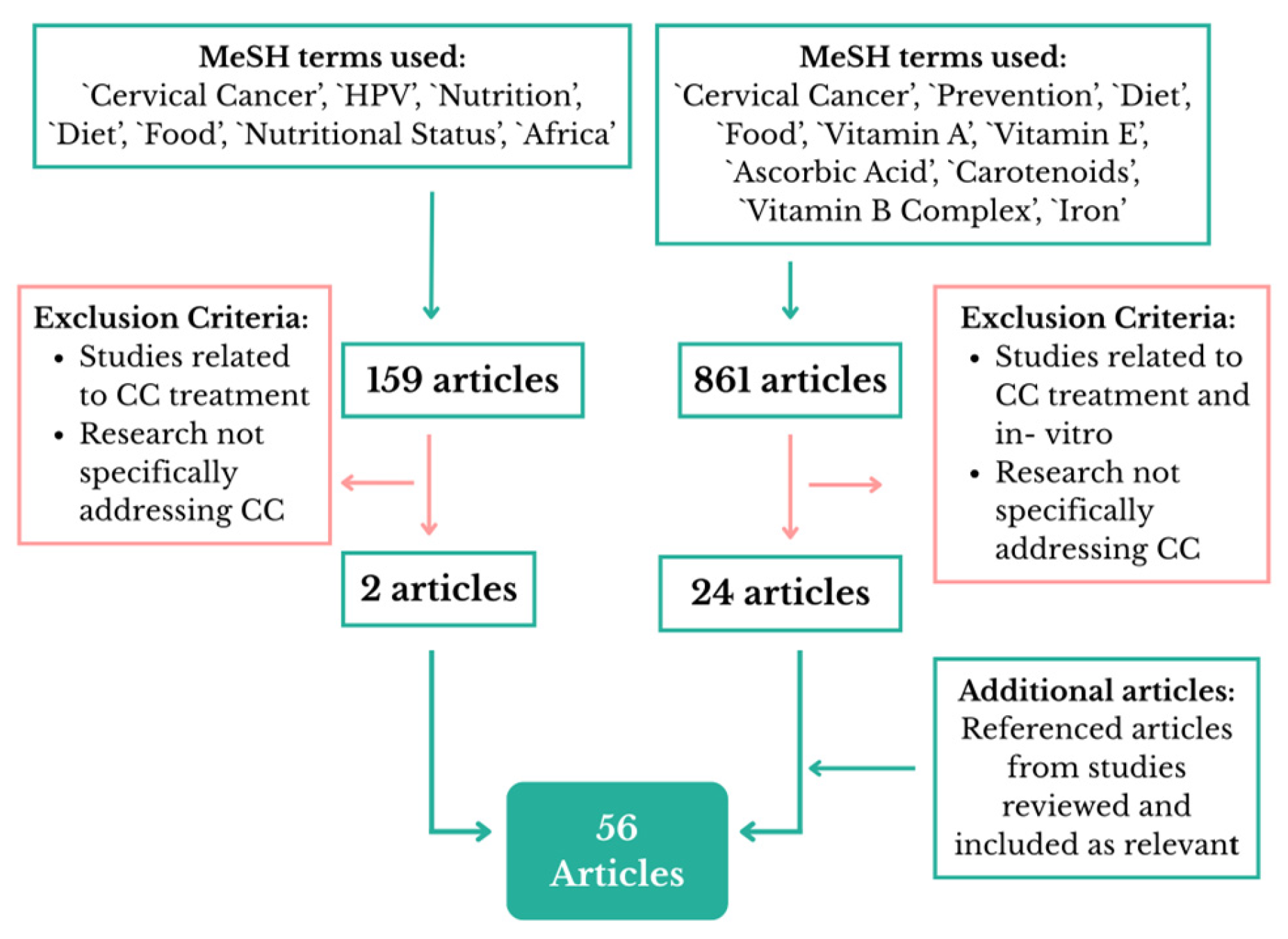

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Articles Selected

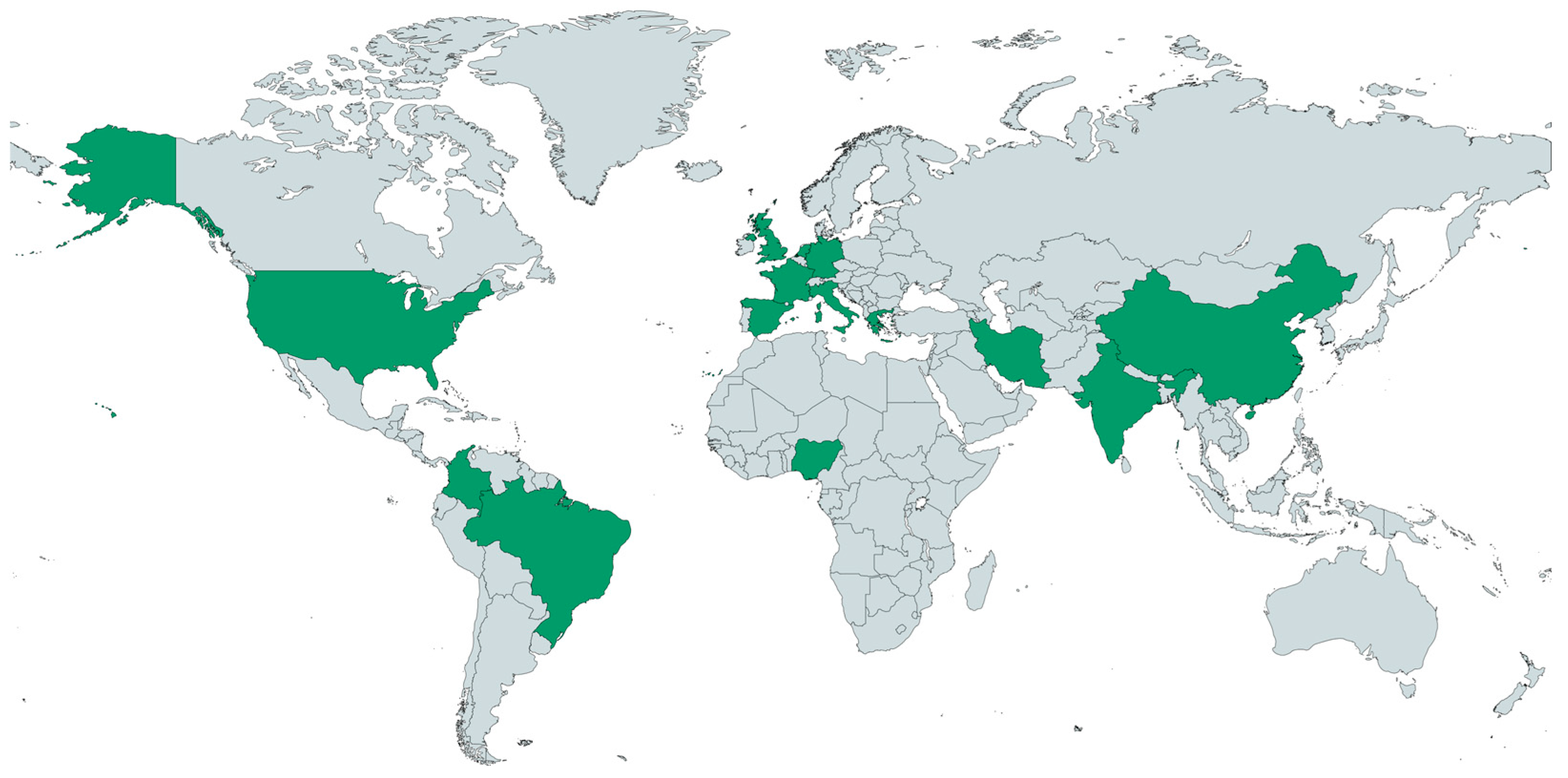

Characteristics of the Selected Studies

3.2. Diet and Cervical Cancer

3.2.1. Water-Soluble Vitamins

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age (Years) HIV/HPV+ | Vitamin | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Iran | 2023 | Population-based cross-sectional study. Machine learning model | n = 2088 Mean age 34 | Vitamin B1 Vitamin B3 Vitamin B6 Vitamin E | Vitamin–CC: Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) −0.558 (r) Vitamin B3 (Niacin (mg)) −0.648 (r) Vitamin B6 −0.602 (r) Vitamin E −0.730 (r) |

| [13] | Colombia | 2023 | Case–control study (nested in trial) | Cases CIN 2+ (n = 155) Controls ≤ CIN1 (n = 155) Age 20–69 | Folate B9 | Folate deficiencies–CIN3+ (affect DNA methylation): OR 8.9 (95% CI 3.4–24.9) |

| [14] | China | 2022 | Cohort study (cross-sectional analysis of baseline data) | n = 2304 Age 19–65 | Folate (B9) | ↓ serum levels of RBC folate–all CIN. ORs: Q1 vs. Q4: 2.28 (95% CI: 1.77, 2.93). Similar inverse associations for CIN1/2/3+. ↓ serum levels of RBC folate–progression CIN1 to CIN2: Q1 vs. Q4: 3.86; (95%CI:1.01, 14.76) ↑1-unit reduced risk of CIN1 progress to CIN2 (0.67; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.99) |

| [12] | China | 2021 | Prospective cohort. FFQ | N = 564 Age 18+ | Vitamins B1; B3; B7; B9; C | Low levels–CIN persistence and progression: Vitamin B1 (RR 1.86) Vitamin B3 (Niacin) (RR 2.98) Vitamin B6 (RR 2.11) Vitamin B7 (Biotin) (RR 2.14) Vitamin B9 (Folate) (RR 15.22) Vitamin C (RR 2.19) |

| [11] | USA | 2020 | Cohort (NHANES) 24 h recall questionnaire | N = 13471 Age 18–59 | Vitamin B1 (thiamine) | Vitamin B1–HPV infection: OR 0.70 (95% CI 0.63, 0.77). Best preventive effect with intake ≈ 2 mg. Excessive intake does not increase the preventive effect |

| [15] | Iran | 2016 | Randomized, Clinical trial | n = 49 Folate (n = 25) Placebo (n = 24) Ages 18–55 | Folate (B9) | Folate supplementation (5 mg/d) vs. placebo (6 months) promotes CIN1 regression: 83% vs. 52%, (p = 0.019) |

| [17] | Europe * | 2010 | EPIC cohort | n = 299,651 ICS (n = 253) CIS (n = 817) Age 35–70 | Vitamin C | Higher intake of vitamin C–invasive squamous cell CC. HR = 0.59 (95% CI 0.39–0.89) |

| [16] | USA | 2007 | Case–control study FFQ | Cases (n = 239) Controls (n = 979) Age 21–59 | Folate (B9) Vitamin C | Folate intake > 433.2 μg/day–CC: OR = 0.55; (95% CI 0.34–0.88) Vit C intake > 224 g/day–CC: OR = 0.53; (95%CI 0.33–0.8) |

| [18] | India | 2002 | Case–control | Cases (n = 30) Controls (n = 30) Age 35–55 | Vitamin C | Vitamin C plasma levels are lower in cases vs. controls |

3.2.2. Liposoluble Vitamins

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age (Years) HIV/HPV+/− | Vitamin | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Iran | 2023 | Population-based cross-sectional study. (MLM) | n = 2088 Mean age 34 | Vitamin E | Vitamin E–CC correlation: −0.730 (r) |

| [28] | China | 2020 | Cohort | n = 2304 Age 18–60+ | Vitamin K | Vit–CIN2+ (for optimal dose): Q2 OR 1.53 (95% CI 1.02–2.29) |

| [23] | USA | 2020 | Cohort (NHANES) | n = 5809 Age 18–59 | Vitamin E | Vitamin E–HPV infection (especially hrHPV) Q4 vs. Q1 OR 0.72 (95%CI 0.65–0.80) |

| [26] | Iran | 2016 | Randomized-placebo-controlled clinical trial | n = 58. Age 18–55, CIN1 diagnosis | Vitamin D | Supplementing 50,000 IU every 14 days 6 months was associated with a higher regression vs. placebo |

| [27] | USA | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | Age 18+, HPV+ | Vitamin D | Decrease in serum Vit. D levels (per 10 ng/mL)-hrHPV prevalence OR 1.14 (95% CI 1.02–1.27) |

| [17] | Europe * | 2010 | Prospective cohort study | n = 299,651 ICS (n = 253). CIS (n = 817) Age 35–70 | Vitamin D | Higher intake–invasive squamous cell CC. HR = 0.47 (95% CI 0.3–0.76) |

| [29] | Japan | 2010 | Case–control | Cases (n = 405) Controls (n = 2025) Age 18+ | Vitamin D | Intakes ≥162 IU/day confer protection OR 0.64 (95% CI 0.43–0.94) |

| [21] | Korea | 2010 | Case–control | Cases (n = 144) Controls (n = 288) Age 18+ | Vitamin A | Total intakes of vitamins A were strongly inversely associated with cervical cancer risk: OR = 0.35 (95% CI 0.19–0.65). |

| [24] | Brazil | 2010 | Case–control | Control n = 453. Cases: - CIN 1- 2 (n = 186) - CIN3 (n = 231) IC (n = 108) Age 21–65, HIV− | Alpha- Tocopherols Gamma- Tocopherols | Increasing levels of serum a–tocopherol: CIN2: OR 0.45 (%95 CI 0.25–0.81) CIN3: OR 0.26 (%95 CI 0.15–0.47) Increasing levels of serum g-tocopherol: CIN3: OR 0.46 (%95 CI 0.29–0.73) |

| [16] | USA | 2007 | Case–control | Controls (n = 979)Cases (n = 239) Age 21–59 | Vitamin AVitamin E | Vit A intake of >12.7 IU/day–CC: OR = 0.47; (95% CI 0.3–0.73) Vit E intake of >8.9 mg/day–CC: OR = 0.44 (95% CI 0.27–0.72) |

| [18] | India | 2002 | Case–control | - Cases (n = 30) - Controls (n = 30) Age 35–55 | Vitamin E | Vitamin E plasma levels are lower in cases vs. controls |

| [25] | USA | 1997 | Prospective cohort | n = 123 Ages 18+. Low-income | Alpha-tocopherols | Serum concentrations were lower among women two times HPV+. Independent of HPV status, lower serum levels correlated with higher grade of cervical dysplasia Normal 21.57 uM/CIN 1 21.18 uM/CIN 2 18.10 uM/CIN 3 17.27 u |

| [20] | USA | 1992 | Pilot case–control | Cases (n = 58) Controls (n = 42) Age 18+ | Vitamin A (retinol) | Low retinol intake is associated with an increased risk of CIN 1 Q1 vs. Q4: OR = 2.3, (95% CI 1.3–4.1). |

3.2.3. Minerals

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age (years) HIV/HPV+ | Mineral | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Iran | 2023 | Population-based cross-sectional study. (MLM) | n = 2088 Mean age 34 | Iron (Fe) Zinc (Zn) Potassium (K) Copper (Cu) | Strong correlation between mineral intake and a preventive effect regarding CC phase progression Fe: −0.671/−0.678 (r) Zn: −0.678/−0.731 (r) K: −0.574/−0.725 (r) Cu: −0.602/−0.731 (r) |

| [35] | Iran | 2022 | Randomized clinical trial | n = 80 (40 controls, 40 cases) Ages 21–55, HPV+ | Zinc | Oral Zn sulfate associated with higher rates of HPV clearance and regression of cervical pathology. OR 0.13 (CI 95% 0.04–0.381) |

| [36] | USA | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | n = 4628 Age 16–59 | Zinc Copper | Zn intake (Q4 vs. Q1)–hrHPV: OR 0.72 (95% CI 0.54–0.98) Cu intake (Q3 vs. Q1)–hrHPV: OR 0.67 (95% CI, 0.50–0.90) Zn intake (RDA established vs. below RDA)–hrHPV OR: 0.74; (95% CI 0.60–0.92) |

| [30] | USA | 2020 | Secondary analysis | n = 13,475 Age 18–59 | Calcium (Ca) | Dietary Ca intake (log2) significantly associated with a 17% lower risk of HPV OR 0.83 (95% CI 0.70, 0.98) |

| [34] | Italy | 2020 | Cross-sectional study. | n = 251 Age 18+ | Zinc | Zn negatively associated hrHPV risk (p < 0.001). Immunomodulatory properties. |

| [37] | Nigeria | 2019 | Case–control | - Controls (n = 45) - CIN cases (n = 45) Age ≤ 65 | Selenium (Se) | Serum levels different between different CIN grades (p = 0.021). Linear trend (p = 0.025) Se can be used as cofactor to modulate HPV progression to cCC. |

| [33] | Brazil | 2013 | Cohort study (Ludwig–McHill) | n = 327 Age 18–60, HPV+ | Iron | Clearance was less likely in women whose Fe serum levels were above the median. HR = 0.73 (95% CI 0.55–0.96) Rising Fe stores (≥120 ug/L) may decrease the probability of clearing a new HPV infection. HR = 0.34 (95%CI 0.15–0.81) |

| [29] | Japan | 2010 | Case–control | - Cases (n = 405) - Control (n = 2025) Age 18+ | Calcium | ≥502.6 mg/day confer protection. OR 0.5; 95% CI = 0.35–0.73 |

| [31] | Japan | 2010 | Cross-sectional study | n = 1096 Age 18–65 | Calcium | Ca supplements significantly associated with a lower risk of CIN 2/3. OR 0.21 (95% CI (0.08–0.50) |

3.2.4. Other Nutrients

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age(years)HIV/HPV+ | Nutrient | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | USA | 2021 | Cohort (NHANES) | n = 11,070 Age 18–59 | Albumin, Nutritional Antioxidant Score (NAS) (Include VitA, B2, E, B9) | Lowerserum albumin levels–increased risk of hrHPV <39 g/L OR 1.4 (95%CI 1.1–1.) Higher NAS associated with lower odds of hrHPV infection. Low vs. high NAS OR 1.3 (1–1.7); lrHPV: Low vs. high NAS OR 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

| [38] | China | 2015 | Hospital-based case–control | Cases (n = 200) Controls (n = 158) Age 18+ | α-carotene β-carotene Lutein Tocopherols | High concentrations of carotenoids and tocopherols associated with low CC risk α-carotene OR 0.42 (0.26, 0.66) β-carotene OR 0.31 (0.20, 0.47)Lutein OR 0.53 (0.35, 0.79) (p 0.003) - ocopherols OR 0.39 (0.26, 0.58) |

| [24] | Brazil | 2010 | Case–control | Control n = 453 - CIN 1- 2 (n = 286) - CIN3 (n = 231) - Invasive cancer (n = 108) Age 21–65, HIV− | Lycopene Carotenoids | Increasing levels serum lycopene decrease CIN 3 [OR 0.43 (%95 CI 0.27–0.68)], invasive cancer [OR 0.17 (%95 CI 0.08–0.35)]. Increasing total levels of serum carotenoids decrease the risk of CIN 3 [OR 0.39 (%95 CI 0.25–0.62)], invasive cancer [OR 0.19 (%95 CI 0.09–0.38)] |

| [16] | USA | 2007 | Case–control | Controls (n = 979) - Cases (n = 239) Age 21–59 | Fiber α-carotene β-carotene Lutein Lycopene | >29 g fiber/day—OR = 0.59; (95% CI 0.37–0.94) ↓ risk of CC >1.393 μg α-carotene/day—OR = 0.41 (95% CI 0.27–0.63) ↓ risk of CC >7.512 μg β-carotene/day—OR = 0.44; (95%CI 0.29–0.68) ↓ risk of CC >6558 μg lLtein/day—OR = 0.51 (95% CI 0.33–0.79) ↓ risk of CC >5.837 μg lycopene/day—OR = 0.65 (95% CI 0.44–0.98) ↓ risk of CC |

3.2.5. Foods

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age HIV/HPV+/− | Food | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Iran | 2023 | Population-based cross-sectional study. (MLM) | n = 2088 Mean age 34 | Dairy products | Strong positive correlation with CC. Yogurt (r = 0.778), Milk (r = 0.775) |

| [23] | USA | 2023 | Cohort (NHANES) | n = 11,070 Age 18–59 | Fruits Whole fruits Greens and beans | Lower intake of these is associated with hrHPV infection. Fruit intake for women with hrHPV infection vs. no hrHPV: 2.5 to 5 pieces a day: (Fruits/whole fruits/greens and beans) 95% CI OR 0.61 (0.45–0.85)/OR 0.57 (0.42–0.78)/OR 0.61 (9.47–0.80) More than 5 pieces a day: OR 0.57 (0.42–0.78)/OR 0.62 (0.47–0.81)/OR 0.68 (0.55–0.83) |

| [45] | China | 2012 | Matched case–control (ratio 1:9) | - Cases (n = 102) - Controls (n = 963) Diagnosis of CIN 2, 3 or CC. Age 28–61 | Vegetables | A higher intake of fresh vegetables could decrease the risk of CC OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.81–0.99) |

| [17] | Europe * | 2010 | Prospective cohort study | n = 299,651 ISC (n = 253). CIS (n = 817) Age 35–70 | Fruits Vegetables Leafy vegetables | Consumption of 100 g is inversely associated with ISC Fruits: HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.72–0.98 Vegetables: HR 0.85: 95% CI 0.65–1.10 Higher consumption of leafy vegetables is associated with a lower risk of developing invasive squamous cell CC. HR = 0.52 (95% CI 0.29–0.95) |

| [47] | Brazil | 2010 | Cohort study (Ludwig–McHill) | n = 327 Age 18–60, HPV+ | Fruit | Orange consumption ≥1 time/week decreases the risk of squamous intracellular lesions for HPV+ women. OR 0.32 (95% CI 0.12–0.87) |

| [48] | China | 2001 | Cross-sectional population-based study | n = 2338 - Normal cervix (n = 2143) - CIN2 + (n = 195) Age 35–50 | Onion Legumes Nuts Meat | Intake of >15.95 servings per week is associated with a lower risk of the development of CIN+. OR = 0.65 (95% CI 0.44–0.988) Intake of >2.69 servings per week is associated with a lower risk of the development of CIN+. OR = 0.65; (95% CI 0.44–0.98) Intake of >0.61 servings per week is associated with a lower risk of the development of CIN+. OR = 0.59; (95% CI 0.39–0.88) Intake of >0.94 servings per week is associated with a lower risk of the development of CIN+. OR = 0.65; (95% CI 0.43–0.99) |

| [24] | Brazil | 2009 | Case–control | Control n = 453 - CIN 1- 2 (n = 286) - CIN3 (n = 231) - Invasive cancer (n = 108) Age 21–65, HIV− | Carrots | 203–1321 g carrots/day protective CIN3: OR 0.46 (%95 CI 0.31–0.70). |

| [43] | Korea | 2010 | Cohort study | n = 1096 Age 18–65 y | Fruits Vegetables | Low fruit intake (<109 g/d) in women with high viral load for hrHPV infection is associated with a higher risk of developing CIN 2/3 compared to women with a decreased viral load. OR = 2.93 (95% CI 1.25–6.87) Low vegetable intake (<302 g/d) in women with a high viral load for hrHPV infection: increase in risk of CIN 2/3 compared to those with a lower viral load. OR 2.84 (1.26–6.42) |

| [44] | Brazil | 2009 | Hospital-based case–control | - Control n = 453 - CIN1 (n = 140) - CIN2 (n = 126) - CIN3 (n = 231) - Invasive cancer (n = 108) Ages 21–65, HIV− | Green and yellow produce Fruit and juice Fruits and vegetables | Consumption of ≤39 g/d green and yellow produce is associated with CIN 3. OR = 1.71 (95% CI = 1.15–2.52) Consumption of ≤79 g/d of fruit and juice is associated with CIN 3. OR = 1.44 (95% CI = 1.02–2.03) Consumption of ≤319 g/d of fruits and vegetables is associated to CIN 3. OR = 1.52 (95% CI 1.06–2.17) |

| [46] | USA | 2002 | Prospective cohort study | n = 1042 Age 18–35 | Vegetables | Higher consumption of vegetables (>207 g/day) is associated with decreased risk of HPV persistence. OR 0.46 (0.21–0.97) |

3.2.6. Functional Foods

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age HIV/HPV+ | Functional Food | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | China | 2024 | Controlled pilot study | n = 100 - Lactobacillus (n = 50) - Placebo (n = 50) Age 18–65, R- hrHPV+ | Probiotics Lactobacillus crispatus (L. crispatus) | Intravaginal probiotics (L. crispatus) were successful for the following: - Effective HPV clearance: Probiotics vs. placebo 12.13% higher (p > 0.05). - Cytological improvement rate: 82.14% vs. 77.78%, both p < 0.05. - Significantly improved vaginal microbiota, with a downward trend in Gardnerella and Prevotella (p < 0.01). |

| [51] | India | 2024 | Review | Age 30–69, CC diagnosis | Probiotics Lactobacillus Bifidobacterium | Some Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains have shown anticancer activities against CC and were found to be helpful in combating side effects |

3.2.7. Specific Diets and Dietary Patterns

| Ref. | Country | Year of Publication | Study Design Data Collection | Sample Size Population Age HIV/HPV+ | Dietary Pattern | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | Colombia | 2023 | Multi-group ecological study | n = 3472 Age 35–64 | Conservative pattern | This is related to a lower incidence of CC. |

| [7] | Italy | 2022 | Cross-sectional study | n = 539 Age 18+ | Pro-inflammatory diet | High adherence to this diet-increased risk of CIN2 or severe lesions. OR 3.14 (95% CI 1.50–6.56). |

| [55] | Korea | 2020 | Case–control | n = 1340 Age 18–65 | High glycemic load | Diets with high glycemic load significantly associated with CIN1 risk: OR 2.8 (95% CI 1.33–5.88). |

| [53] | Italy | 2018 | Cross-sectional study | Age 18+. n = 539 - Normal cervical epithelium (n = 252) - CIN1–2 (n = 217) - CIN3+ (n = 70) | Mediterranean diet (MD) Prudent diet | Medium adherence to MD linked to a lower risk of hrHPV infection. OR = 0.43 (95% CI 0.22–0.73). Adherence to Prudent diet is protective against development of CIN 2+. OR = 0.50 (95% CI 0.26–0.98). |

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.1.1. Water-Soluble Vitamins

4.1.2. Liposoluble Vitamins

4.1.3. Minerals

4.1.4. Other Nutrients

4.1.5. Foods

4.1.6. Functional Foods

4.1.7. Specific Diets and Dietary Patterns

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Cervical cancer |

| CIN | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia |

| CIS | Carcinoma in situ |

| GL | Glycemic load |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| hrHPV | High-risk Human Papillomavirus |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| ISC | Invasive squamous cervical cancer |

| lrHPV | Low-risk Human Papillomavirus |

| MD | Mediterranean diet |

| NAS | Nutritional Antioxidant Score |

| SSA | sub-Saharan Africa |

| STI | Sexually transmitted infection |

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Today. Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Cervical Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Originally Published by the National Cancer Institute. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/causes-risk-prevention#:~:text=HPV%20infection%20causes%20cervical%20cancer,70%25%20of%20cervical%20cancers%20worldwide (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Luhn, P.; Walker, J.; Schiffman, M.; Zuna, R.; Dunn, T.; Gold, M.A.; Smith, K.; Mathews, C.; Allen, R.A.; Zhang, R.; et al. The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 128, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Sharma, M.; Tan, N.; Barnabas, R. HIV-positive women have higher risk of human papillomavirus infection, precancerous lesions, and cervical cancer. AIDS 2018, 32, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-Y.; Li, G.; Gong, T.-T.; Lv, J.-L.; Gao, C.; Liu, F.-H.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Wu, Q.-J. Non-genetic factors and risk of cervical cancer: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1605198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimple, S.; Gauravi, M. Cancer cervix: Epidemiology and disease burden. CytoJournal 2022, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; San Lio, R.M.; Scalisi, A.; Agodi, A. Antioxidant and inflammatory potential of diet among women at risk of cervical cancer: Findings from a cross-sectional study in Italy. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Fu, Q.; Kao, Y.-H.; Tseng, T.-S.; Reiss, K.; Cameron, J.E.; Ronis, M.J.; Su, J.; Nair, N.; Chang, H.-M.; et al. Antioxidants associated with oncogenic human papillomavirus infection in women. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A.; Koshiyama, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Ikuta, E.; Seki, K.; Oowaki, M. The preventive effect of dietary antioxidants on cervical cancer development. Medicina 2020, 56, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, E.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Rezvani, R.; Rejali, M.; Badpeyma, M.; Delaram, Z.; Mousavi-Seresht, L.; Akbari, M.; Khazaei, M.; Ferns, G.A.; et al. Association of dietary intake and cervical cancer: A prevention strategy. Infect. Agents Cancer 2023, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.-X.; Zhu, F.-F.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Lv, X.-L.; Li, J.-W.; Luo, S.-P.; Gao, J. Association of Thiamine Intake with Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection in American Women: A Secondary Data Analysis Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2003 to 2016. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e924932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, L.; Qi, Z.; Meng, D.; Wang, J.; Lyu, Y.J.; Jia, H.X.; Ding, L.; Hao, M.; Tian, Z.Q.; et al. Effect of dietary water-soluble vitamins on the poor prognosis of low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia—A prospective cohort study. J. Chin. Epidemiol. 2021, 46, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, M.C.; Agudelo, S.; Lorincz, A.; Ramírez, A.T.; Castañeda, K.M.; Garcés-Palacio, I.; Zea, A.H.; Piyathilake, C.; Sanchez, G.I. Folate deficiency modifies the risk of CIN3+ associated with DNA methylation levels: A nested case-control study from the ASCUS-COL trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, A.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Lou, H.; Wang, W.; Liang, T.; et al. Associations of RBC and serum folate concentrations with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes in female Chinese adults. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asemi, Z.; Vahedpoor, Z.; Jamilian, M.; Bahmani, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Effects of long-term folate supplementation on metabolic status and regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition 2016, 32, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Baker, J.A.; Moyisch, K.B.; Rivera, R.; Brasure, J.R.; McCann, S.E. Dietary intakes of selected nutrients and food groups and risk of cervical cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.A.; Travier, N.; Lujan-Barroso, L.; Castellsagué, X.; Bosch, F.X.; Roura, E.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Palli, D.; Boeing, H.; Pala, V.; et al. Dietary factors and in situ and invasive cervical cancer risk in the EPIC study. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manju, V.; Sailaja, J.K.; Nalini, N. Circulating lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in cervical cancer patients: A case-control study. Clin. Biochem. 2002, 35, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G. Bioconversion of dietary provitamin A carotenoids to vitamin A in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1468S–1473S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, A.S.; Schiff, M.A.; Montoya, G.; Masuk, M.; van Asselt-King, L.; Becker, T.M. Serum Micronutrients and Cervical Dysplasia in Southwestern American Indian Women. Nutr. Cancer 2000, 38, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Son, S.K.; Song, E.S.; Lee, K.B.; Lee, J.P.; Lee, J.M.; Yun, Y.M. Intakes of vitamin A, C, and E, and beta-carotene are associated with risk of cervical cancer: A case-control study in Korea. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Yu, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Ma, S.; Liu, B.; Cai, H. Dietary Vitamin A Intake and Circulating Vitamin A Concentrations and the Risk of Three Common Cancers in Women: A Meta-Analysis. Oxid. Med. Cel. Long. 2022, 2022, 7686405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Fan, M.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Si, H.; Dai, G. Association between Dietary Vitamin E Intake and Human Papillomavirus Infection Among US Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, L.Y.; Filho, A.L.; Costa, M.C.; Andreoli, M.A.A.; Villa, L.; Franco, E.L.; Cardoso, M.A.; BRINCA Study Team. Diet and serum micronutrients in relation to cervical neoplasia and cancer among low-income Brazilian women. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, A.R.; Papenfuss, M.; Nour, M.; Canfield, L.M.; Schneider, A.; Hatch, K. Antioxidant nutrients: Associations with persistent human papillomavirus infection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1997, 6, 917–923. [Google Scholar]

- Vahedpoor, Z.; Jamilian, M.; Bahmani, F.; Aghadavod, E.; Karamali, M.; Kashanian, M.; Asemi, Z. Effects of Long-Term Vitamin D Supplementation on Regression and Metabolic Status of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Horm. Cancer 2017, 8, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Perez, A.; Symanski, E.; Nyitray, A.G. Association Between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Level and Human Papillomavirus Cervicovaginal Infection in Women in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, A.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Li, L.; Lv, W.; et al. Dietary nutrient intake related to higher grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia risk: A Chinese population-based study. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, S.; Matsuo, K.; Kajiyama, H.; Hirose, K.; Suzuki, T.; Kawase, T.; Kidokoro, K.; Nakanishi, T.; Hamajima, N.; Kikkawa, F.; et al. Association between dietary calcium and vitamin D intake and cervical carcinogenesis among Japanese women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, A.-J.; Chen, C.; Jia, M.; Fan, R.-Q. Dietary Calcium Intake and HPV Infection Status Among American Women: A Secondary Analysis from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Data Set of 2003–2016. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e921571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, J.K. Dietary supplements reduce the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2010, 20, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.; Villa, L.; Rohan, T.; Ferenczy, A.; Petzl-Erler, M.; Matlashewski, G. Design and methods of the Ludwig-McGill longitudinal study of the natural history of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in Brazil. Ludwig-McGill Study Group. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 1999, 6, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, E.M.; Patel, N.; Lu, B.; Lee, J.-H.; Nyitray, A.G.; Huang, X.; Villa, L.L.; Franco, E.L.; Giuliano, A.R. Circulating biomarkers of iron storage and clearance of incident human papillomavirus infection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; La Mastra, C.; La Rosa, M.C.; Favara, G.; San Lio, R.M.; Agodi, A. Dietary Antioxidant Intake and Human Papillomavirus Infection: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study in Italy. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, H.; Rajabi, Q.; Yekta, Z.; Jalali, Z. Efficacy of Oral Zinc Sulfate Supplementation on Clearance of Cervical Human Papillomavirus (HPV); A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.-H.; Wen, Z.; Dai, B.; Mo, W.; Qiu, A.; Yang, L. Dietary Zinc, Copper, and Selenium Intake and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infection Among American Women: Data from NHANES 2011–2016. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 1958–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obhielo, E.; Ezeanochie, M.; Olokor, O.O.; Okonkwo, A.; Gharoro, E. The Relationship Between the Serum Level of Selenium and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Comparative Study in a Population of Nigerian Women. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 1433–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Lu, L.; Abliz, G.; Mijit, F. Serum carotenoid, retinol and tocopherol concentrations and risk of cervical cancer among Chinese women. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2025, 16, 2981–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ghorat, F.; Ul-Haq, I.; Ur-Rehman, H.; Aslam, F.; Heyydari, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Okuskhanova, E.; Yessimbekov, Z.; Thiruvengadam, M.; et al. Lycopene as a Natural Antioxidant Used to Prevent Human Health Disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colombo, F.; Biella, S.; Stockley, C.; Restani, P. Polyphenols and Human Health: The Role of Bioavailability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, H.-G.; Yang, A.; Yan, H.; Cui, Y. Combination of quercetin with radiotherapy enhances tumor radiosensitivity in vitro and in vivo. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 104, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-I.; Shim, J.-H.; Kim, K.-H.; Choi, H.-S.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, H.-G.; Kim, B.-Y.; Park, S.-N.; Park, O.-J.; Yoon, D.-Y. Sensitization of the apoptotic effect of gamma-irradiation in genistein-pretreated aSki cervical cancer cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 523–531. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, M.K. The association between fruit and vegetable consumption and HPV viral load in high-risk HPV-positive women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer Causes Control 2010, 21, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, L.Y.; Roteli-Martins, C.M.; Villa, L.L.; Franco, E.L.; Cardoso, M.A.; BRINCA Study Team. Associations of dietary dark-green and deep-yellow vegetables and fruits with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Hu, T.; Hang, C.-Y.; Yang, R.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.-L.; Mei, Y.-D.; Zhang, Q.-H.; Huang, K.-C.; Xiang, Q.-Y.; et al. Case-control study of diet in patients with cervical cancer or precancerosis in Wufeng, a high incidence region in China. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 5299–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedjo, R.L.; Roe, D.J.; Abrahamsen, M.; Harris, R.B.; Craft, N.; Baldwin, S.; Giuliano, A.R. Vitamin A, carotenoids, and risk of persistent oncogenic human papillomavirus infection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2002, 11, 876–884. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, E.M.; Salemi, J.L.; Villa, L.L.; Ferenczy, A.; Franco, E.L.; Giuliano, A.R. Dietary consumption of antioxidant nutrients and risk of incident cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 118, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.Y.; Lin, M.; Lakhaney, D.; Sun, H.-K.; Dai, X.-B.; Zhao, F.-H.; Qiao, Y.-L. The association between dietary intake and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or higher among women in a high-risk rural area of china. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2001, 284, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandati, K.; Belagal, P.; Nannepaga, J.S.; Viswanath, B. Role of probiotics in the management of cervical cancer: An update. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 48, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, X.; Wu, F.; Chen, J.; Luo, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, T. Effectiveness of vaginal probiotics Lactobacillus crispatus in women with high-risk HPV infection: A prospective controlled pilot study. Aging 2024, 16, 11446–11459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; Faruk, A.; Ahmad, F.J.; Khan, T.; Mishra, N. It Is All about Probiotics to Control Cervical Cancer. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 16, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolalipour, E.; Mahooti, M.; Salehzadeh, A.; Torabi, A.; Mohebbi, S.R.; Gorji, A.; Ghaemi, A. Evaluation of the antitumor immune responses of probiotic Bifidobacterium bifidum in human papillomavirus-induced tumor model. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 145, 104207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Quattrocchi, A.; Agrifoglio, O.; Scalisi, A.; Agodi, A. The association of dietary patterns with high-risk human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer: A cross-sectional study in Italy. Nutrients 2018, 10, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneses-Urrea, L.A.; Vaquero-Abellan, M.; Villegas, D.; Sandoval, N.B.; Hernández-Carrillo, M.; Molina-Recio, G. Association Between Cervical Cancer and Dietary Patterns in Colombia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeja, S.R.; Seo, S.S.; Kim, M.K. Associations of Dietary Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load and Carbohydrate with the Risk of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Cervical Cancer: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaner, W.S.; Shamarakov, I.O.; Traber, M.G. Vitamin A and Vitamin E: Will the Real Antioxidant Please Stand Up? Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guitian, M.; Reina, G.; Carlos, S. The Role of Nutrition in HPV Infection and Cervical Cancer Development: A Review of Protective Dietary Factors. Cancers 2025, 17, 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183020

Guitian M, Reina G, Carlos S. The Role of Nutrition in HPV Infection and Cervical Cancer Development: A Review of Protective Dietary Factors. Cancers. 2025; 17(18):3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183020

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuitian, Maria, Gabriel Reina, and Silvia Carlos. 2025. "The Role of Nutrition in HPV Infection and Cervical Cancer Development: A Review of Protective Dietary Factors" Cancers 17, no. 18: 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183020

APA StyleGuitian, M., Reina, G., & Carlos, S. (2025). The Role of Nutrition in HPV Infection and Cervical Cancer Development: A Review of Protective Dietary Factors. Cancers, 17(18), 3020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17183020