A Comparative Study of Quality of Life and Oncologic Outcomes in Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Bilateral Oophorectomy vs. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

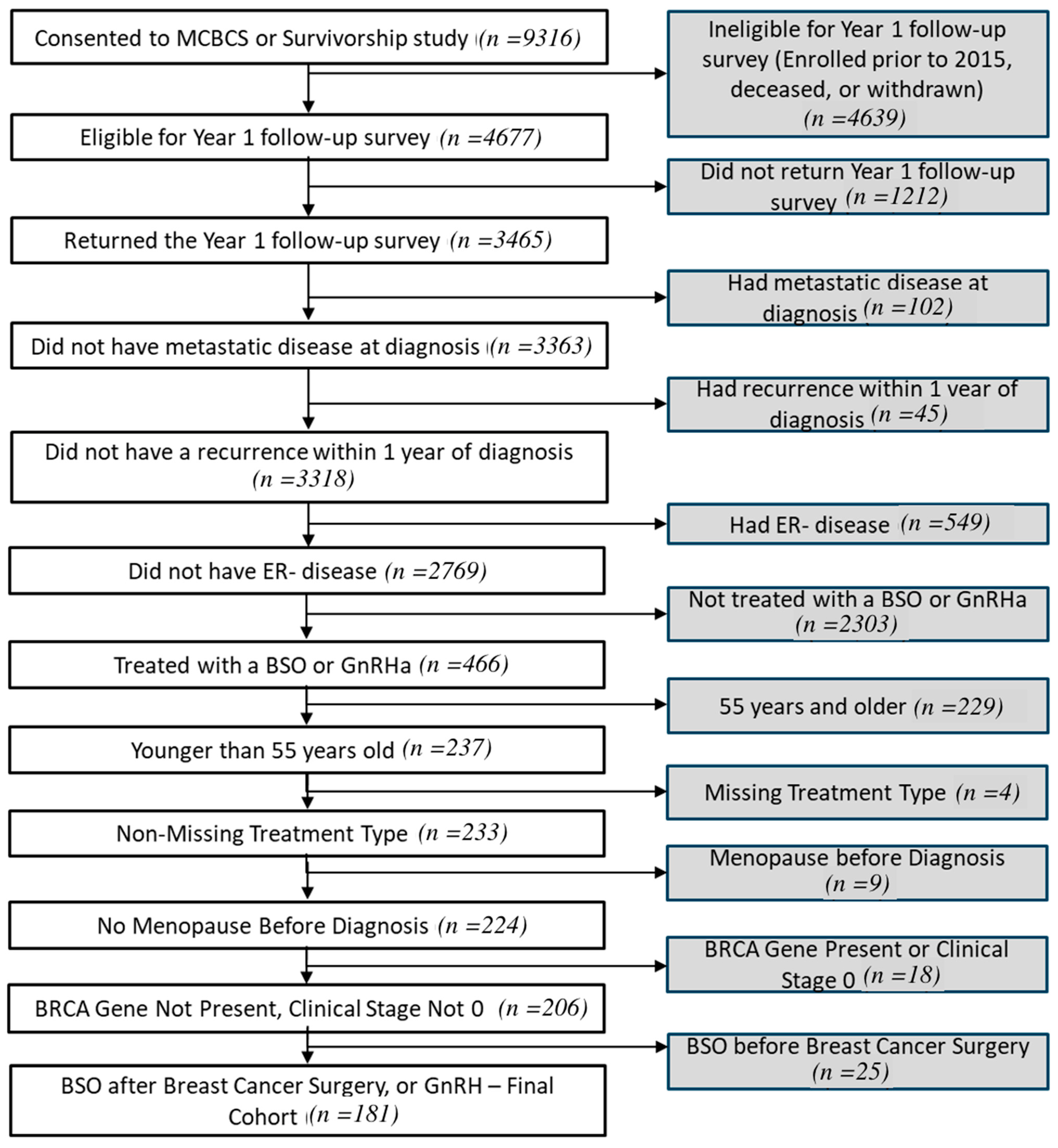

2. Methods

2.1. QoL Assessments

2.2. Data Acquisition and Management

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

| BO (n = 40) | GnRH (n = 141) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (median-IQR) | 46 (42.9–48.3) | 39.8 (33.9, 46.9) | <0.001 |

| Vital status (Alive) at 5-y | 95% | 97.9% | 0.30 |

| Race | 0.64 | ||

| White | 97.5% | 92.9% | |

| Black/African American | - | 0.7% | |

| Asian | - | 4.3% | |

| Other * | 2.5% | 2.1% | |

| Ethnicity (non-Hispanic) | 97.5% | 92.9% | 1.0 |

| Overall Stage | <0.001 | ||

| Stage I | 55.0% | 26.2% | |

| Stage II | 37.5% | 50.4% | |

| Stage III | 7.5% | 23.4% | |

| Surgery Type | 0.07 | ||

| Lumpectomy and Mastectomy | 0 | 5% | |

| Lumpectomy | 37% | 14.9% | |

| Mastectomy and No Lumpectomy | 52.5% | 72,3% | |

| No Mastectomy and No Lumpectomy | 10% | 7.8% | |

| ER Status (Positive) | 100% | 99.3% | 1.0 |

| PR Status (Positive) | 100% | 90.6% | 0.11 |

| HER2 Status (Negative) | 87.2% | 82.7% | 0.32 |

| Recurrence (No) | 97.2% | 95.3% | 1.0 |

| Baseline (Median-IQR) | |||

| Hot Flashes | 0.0 (0.0, 5.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 5.0) | 0.49 |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 0.0 (0.0, 5.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 3.8) | 0.75 |

| At Year 1 | |||

| Hot Flashes | 6.0 (2.0, 7.2) | 4.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 0.02 |

| Sexual Dysfunction | 4.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 0.45 |

| Time between diagnosis and last survey | 4.9 (2.2, 7.1) | 4.0 (2.2, 5.9) | 0.19 |

| Time between diagnosis and Last vital status | 6.0 (3.7, 8.4) | 5.3 (3.5, 7.3) | 0.27 |

3.2. Side Effects

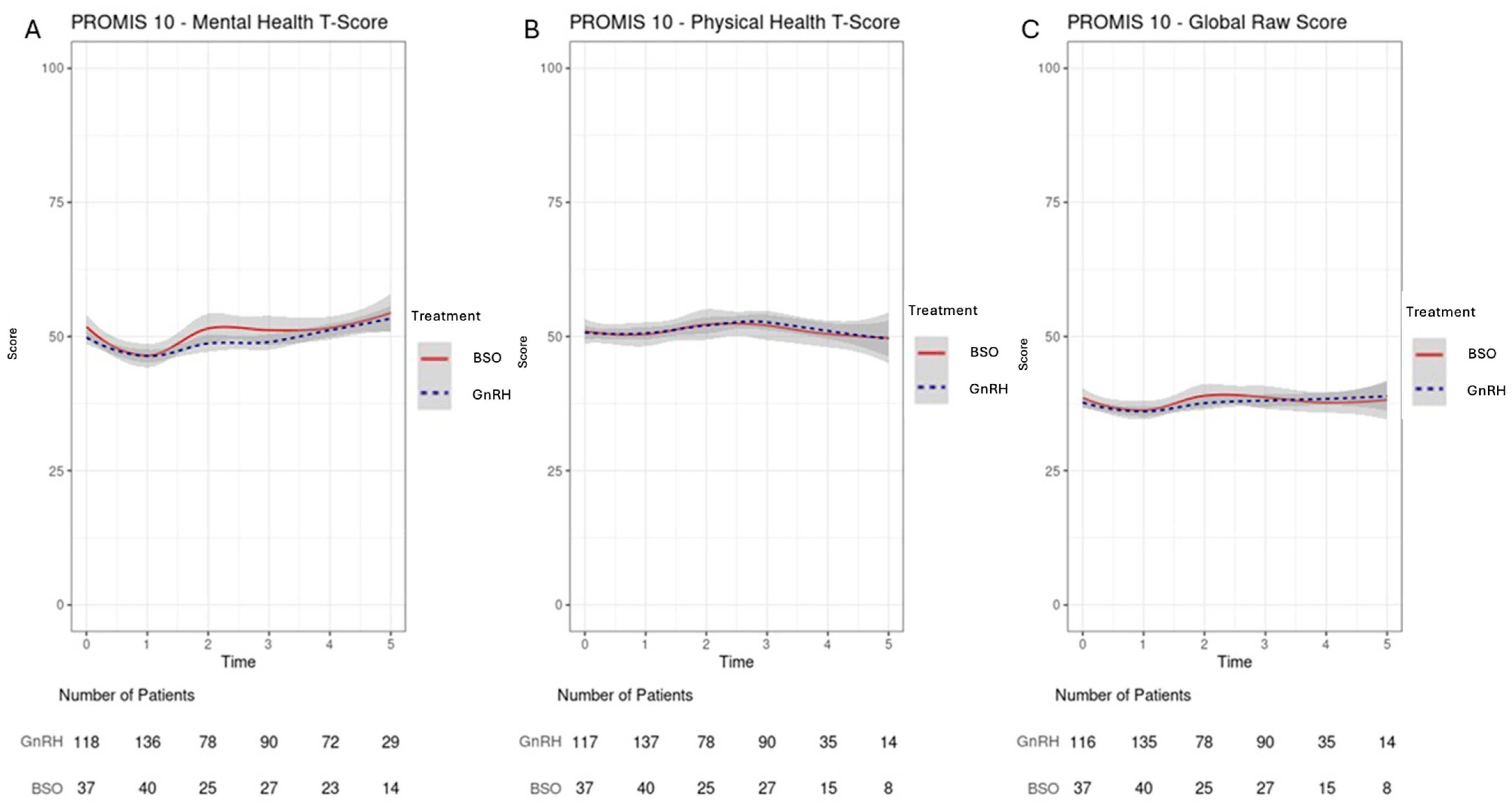

3.3. QoLMeasures

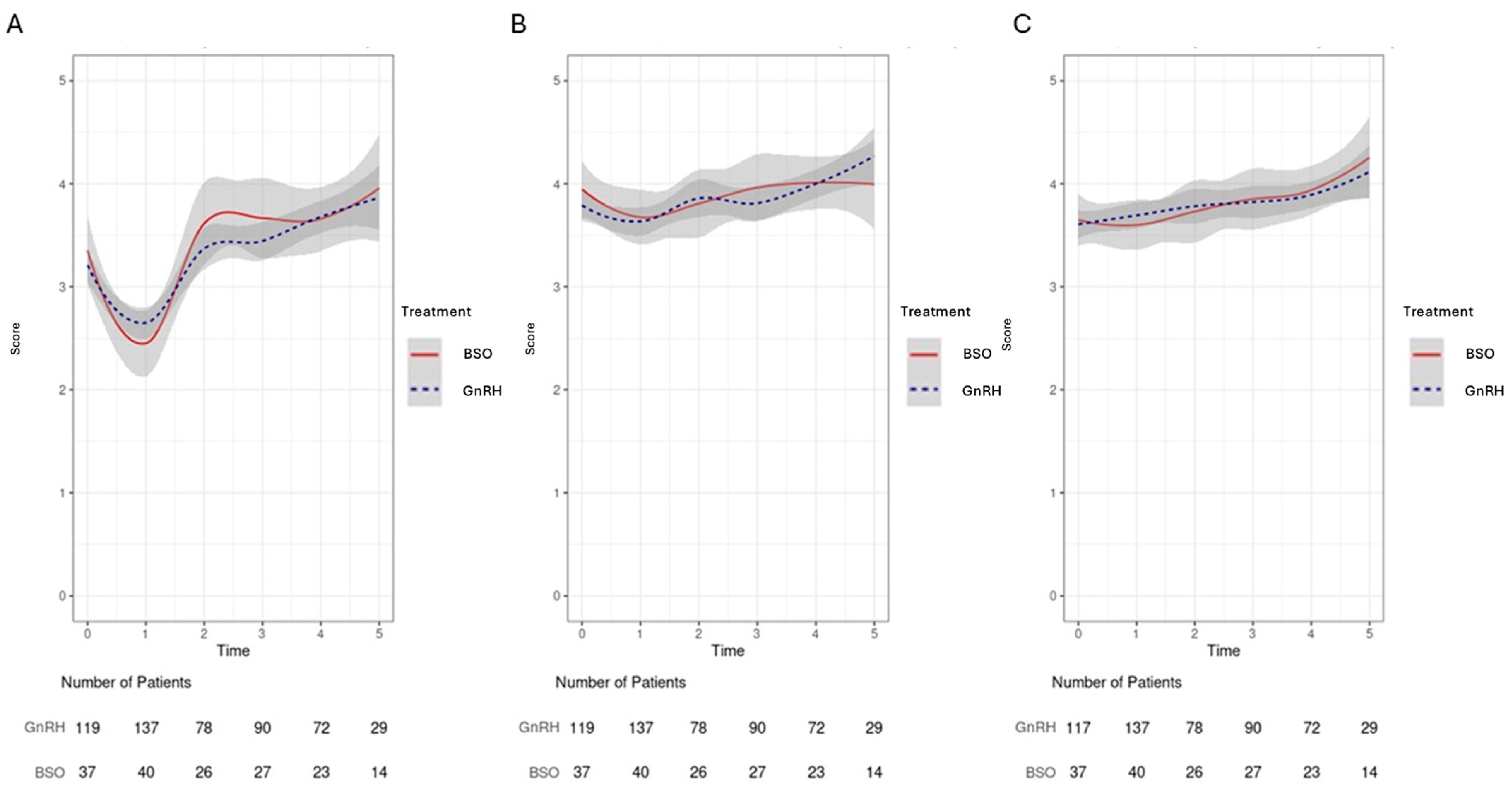

3.4. Domain-Specific QoLAnalysis: Emotional Well-Being/Fatigue/Social Activity/Relationship Satisfaction

3.5. Oncological Outcomes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pagani, O.; O'Neill, A.; Castiglione, M.; Gelber, R.D.; Goldhirsch, A.; Rudenstam, C.M.; Lindtner, J.; Collins, J.; Crivellari, D.; Coates, A.; et al. Prognostic impact of amenorrhoea after adjuvant chemotherapy in premenopausal breast cancer patients with axillary node involvement: Results of the International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) Trial VI. Eur. J. Cancer 1998, 34, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.A.; Fleming, G.F.; Láng, I.; Ciruelos, E.M.; Bonnefoi, H.R.; Bellet, M.; Bernardo, A.; Climent, M.A.; Martino, S.; Bermejo, B.; et al. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Premenopausal Breast Cancer: 12-Year Results From SOFT. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walshe, J.M.; Denduluri, N.; Swain, S.M. Amenorrhea in premenopausal women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5769–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, P.A. Role of Ovarian Suppression in Early Premenopausal Breast Cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 37, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P.; Regan, M.M.; Pagani, O.; Francis, P.A.; Walley, B.A.; Ribi, K.; Bernhard, J.; Luo, W.; Gómez, H.L.; Burstein, H.J.; et al. Treatment Efficacy, Adherence, and Quality of Life Among Women Younger Than 35 Years in the International Breast Cancer Study Group TEXT and SOFT Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3113–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, K.E.; Goldfarb, S.B.; Traina, T.A.; Regan, M.M.; Vidula, N.; Kaklamani, V. Selection of appropriate biomarkers to monitor effectiveness of ovarian function suppression in pre-menopausal patients with ER+ breast cancer. Npj Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, L.T.; Gostout, B.S.; Grossardt, B.R.; Rocca, W.A. Prophylactic oophorectomy in premenopausal women and long-term health. Menopause Int. 2008, 14, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, J.; Luo, W.; Ribi, K.; Colleoni, M.; Burstein, H.J.; Tondini, C.; Pinotti, G.; Spazzapan, S.; Ruhstaller, T.; Puglisi, F.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes with adjuvant exemestane versus tamoxifen in premenopausal women with early breast cancer undergoing ovarian suppression (TEXT and SOFT): A combined analysis of two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.W.; Green, S.; Dalton, W.S.; Martino, S.; Rector, D.; Ingle, J.N.; Robert, N.J.; Budd, G.T.; Paradelo, J.C.; Natale, R.B.; et al. Multicenter randomized clinical trial of goserelin versus surgical ovariectomy in premenopausal patients with receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: An intergroup study. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandina, G.; Amadio, G.; Marcellusi, A.; Azzolini, E.; Puggina, A.; Pastorino, R.; Ricciardi, W.; Scambia, G. Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy Versus GnRH Analogue in the Adjuvant Treatment of Premenopausal Breast Cancer Patients: Cost-Effectiveness Evaluation of Breast Cancer Outcome, Ovarian Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Clin. Drug. Investig. 2017, 37, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Han, S.W.; Kang, E.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, K.; No, J.H.; et al. Bilateral Salpingo-oophorectomy Compared to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists in Premenopausal Hormone Receptor-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Aromatase Inhibitors. Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 49, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseledchyk, A.; Gemignani, M.L.; Zhou, Q.C.; Iasonos, A.; Elahjji, R.; Adamou, Z.; Feit, N.; Goldfarb, S.B.; Long Roche, K.; Sonoda, Y.; et al. Surgical ovarian suppression for adjuvant treatment in hormone receptor positive breast cancer in premenopausal patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Revicki, D.A.; Spritzer, K.L.; Cella, D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorskii, A.; Victorson, D.; O'Connor, P.; Hankin, V.; Safikhani, A.; Crane, T.; Badger, T.; Wyatt, G. PROMIS and legacy measures compared in a supportive care intervention for breast cancer patients and caregivers: Experience from a randomized trial. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 2265–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.X.M.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y.S.; Chang, Y.; Cho, H. Utility of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to measure primary health outcomes in cancer patients: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1723–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023). Health Measures: PROMIS. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=147&Itemid=806 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Rashid, A.A.; Mohammed Hussein, R.A.; Hashim, N.W. Assessing the Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Women: A Cross Sectional Descriptive Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 2299–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinapoli, L.; Colloca, G.; Di Capua, B.; Valentini, V. Psychological Aspects to Consider in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoi, M.A.; Agostinetto, E.; Perachino, M.; Del Mastro, L.; de Azambuja, E.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Partridge, A.H.; Lambertini, M. Evidence-based approaches for the management of side-effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy in patients with breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e303–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, P.E.; Cohen, P.A.; Bulsara, M.K.; Jeffares, S.; Saunders, C. The impact of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy on sexuality and quality of life in women with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, M.; Gray, K.P.; Francis, P.A.; Láng, I.; Ciruelos, E.; Lluch, A.; Climent, M.A.; Catalán, G.; Avella, A.; Bohn, U.; et al. Twelve-Month Estrogen Levels in Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer Receiving Adjuvant Triptorelin Plus Exemestane or Tamoxifen in the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT): The SOFT-EST Substudy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Untch, M.; Kossé, V.; Bondar, G.; Vassiljev, L.; Tarutinov, V.; Lehmann, U.; Maubach, L.; Meurer, J.; Wallwiener, D.; et al. Leuprorelin acetate every-3-months depot versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil as adjuvant treatment in premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer: The TABLE study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2509–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q.J.; O'Dea, A.P.; Sharma, P. Musculoskeletal adverse events associated with adjuvant aromatase inhibitors. J. Oncol. 2010, 2010, 654348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenti, S.; Correale, P.; Cheleschi, S.; Fioravanti, A.; Pirtoli, L. Aromatase Inhibitors-Induced Musculoskeletal Disorders: Current Knowledge on Clinical and Molecular Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, K.C.; Henry, N.L. Adjuvant endocrine therapy in premenopausal women with breast cancer. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 13, 663–672. [Google Scholar]

- Hershman, D.L.; Shao, T.; Kushi, L.H.; Buono, D.; Tsai, W.Y.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Kwan, M.; Gomez, S.L.; Neugut, A.I. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 126, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Shao, T.; Buono, D.; Kershenbaum, A.; Tsai, W.Y.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Gomez, S.L.; Miles, S.; Neugut, A.I. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 4120–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnese, C.; Porciello, G.; Vitale, S.; Palumbo, E.; Crispo, A.; Grimaldi, M.; Calabrese, I.; Pica, R.; Prete, M.; Falzone, L.; et al. Quality of Life in Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer after a 12-Month Treatment of Lifestyle Modifications. Nutrients 2020, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, R.E.; Valente, A.L.; Shriver, C.D.; Bittman, B.; Ellsworth, D.L. Impact of lifestyle factors on prognosis among breast cancer survivors in the USA. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012, 12, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, H.; Williams, R.; Dempsey, H.; Stanway, S.; Smeeth, L.; Bhaskaran, K. Quality of life and mental health in breast cancer survivors compared with non-cancer controls: A study of patient-reported outcomes in the United Kingdom. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo-Fo-Wong, D.N.; de Haes, H.C.; Aaronson, N.K.; van Abbema, D.L.; den Boer, M.D.; van Hezewijk, M.; Immink, M.; Kaptein, A.A.; Reyners, A.K.; Russell, N.S.; et al. Predictors of enduring clinical distress in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 158, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, H.J.G.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Verhagen, C.; Knoop, H. The relationship of fatigue in breast cancer survivors with quality of life and factors to address in psychological interventions: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsevick, A.; Frost, M.; Zwinderman, A.; Hall, P.; Halyard, M. I'm so tired: Biological and genetic mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curt, G.A.; Breitbart, W.; Cella, D.; Groopman, J.E.; Horning, S.J.; Itri, L.M.; Johnson, D.H.; Miaskowski, C.; Scherr, S.L.; Portenoy, R.K.; et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: New findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist 2000, 5, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, E.M.; Garssen, B.; Cull, A.; de Haes, J.C. Application of the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI-20) in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 1996, 73, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrykowski, M.A.; Schmidt, J.E.; Salsman, J.M.; Beacham, A.O.; Jacobsen, P.B. Use of a case definition approach to identify cancer-related fatigue in women undergoing adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6613–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Minton, O.; Andrews, P.; Stone, P. A comparison of the characteristics of disease-free breast cancer survivors with or without cancer-related fatigue syndrome. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Liu, C.; Ren, R.; Xing, W. Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors' Experience of Social Reintegration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. Psychooncology 2025, 34, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.C.; Landis, L.L. Reintegration and maintenance of employees with breast cancer in the workplace. Aaohn J. 1989, 37, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriyanto, D.R.; Prihantono Syamsu, S.A.; Kusuma, M.I.; Hendarto, J.; Indra; Smaradania, N.; Sampepajung, E.; Mappiwali, A.; Faruk, M. Comparison of outcomes in patients with luminal type breast cancer treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: A cohort retrospective study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 77, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erdemoglu, E.; Ruddy, K.J.; Buras, M.R.; Quillen, J.; Couch, F.J.; Olson, J.E.; Bozzuto, L.M.; Larson, N.L.; Yi, J.; Butler, K.A. A Comparative Study of Quality of Life and Oncologic Outcomes in Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Bilateral Oophorectomy vs. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172916

Erdemoglu E, Ruddy KJ, Buras MR, Quillen J, Couch FJ, Olson JE, Bozzuto LM, Larson NL, Yi J, Butler KA. A Comparative Study of Quality of Life and Oncologic Outcomes in Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Bilateral Oophorectomy vs. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy. Cancers. 2025; 17(17):2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172916

Chicago/Turabian StyleErdemoglu, Evrim, Kathryn J. Ruddy, Matthew R. Buras, Jaxon Quillen, Fergus J. Couch, Janet E. Olson, Laura M. Bozzuto, Nicole L. Larson, Johnny Yi, and Kristina A. Butler. 2025. "A Comparative Study of Quality of Life and Oncologic Outcomes in Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Bilateral Oophorectomy vs. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy" Cancers 17, no. 17: 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172916

APA StyleErdemoglu, E., Ruddy, K. J., Buras, M. R., Quillen, J., Couch, F. J., Olson, J. E., Bozzuto, L. M., Larson, N. L., Yi, J., & Butler, K. A. (2025). A Comparative Study of Quality of Life and Oncologic Outcomes in Premenopausal Women with Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Bilateral Oophorectomy vs. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy. Cancers, 17(17), 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17172916