Impact of COVID-19 on the Stage and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: A Cancer Registry Analysis from an Italian Comprehensive Cancer Center

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources of Information

2.2. Analysis of Data

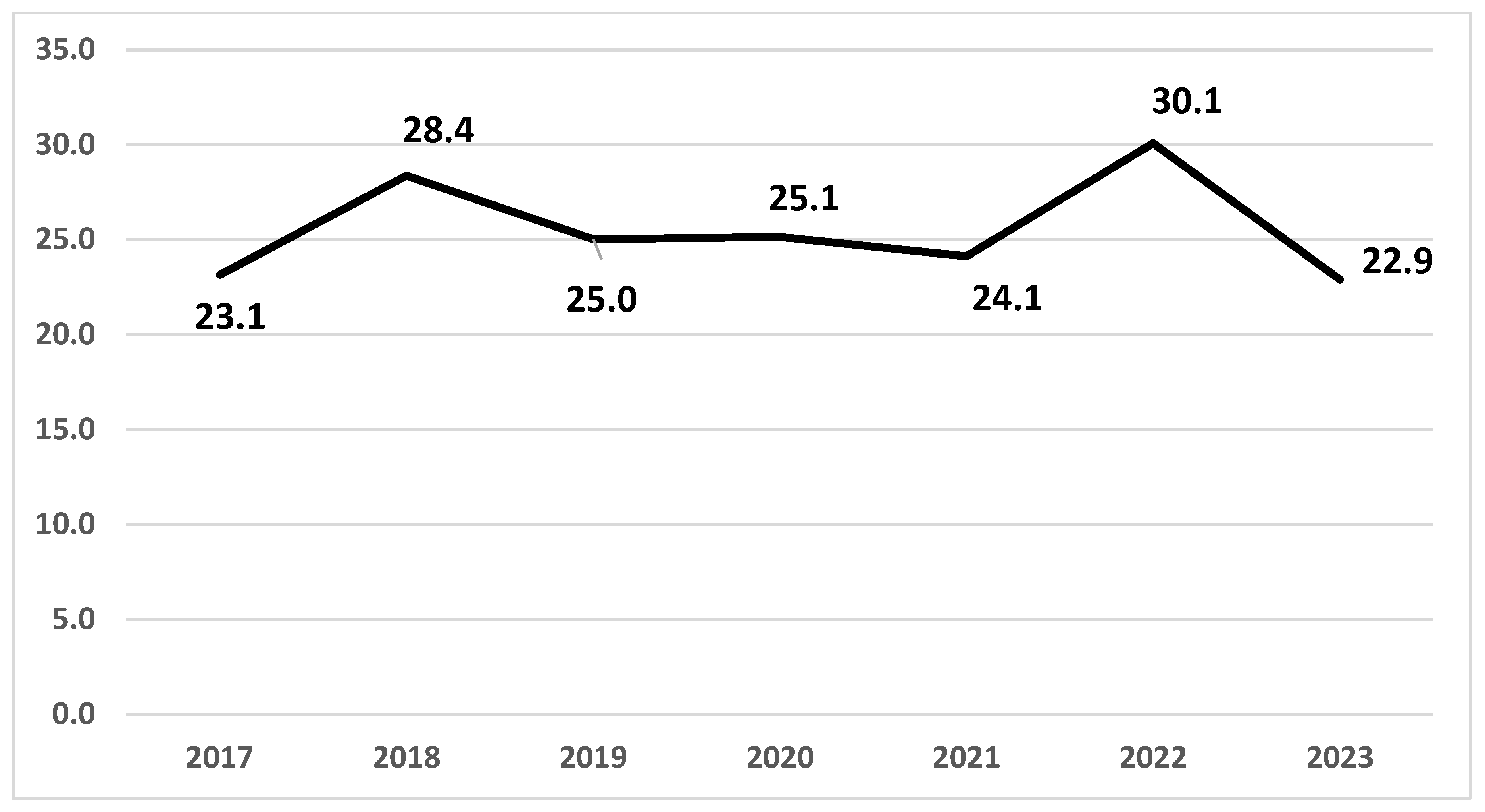

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of Published Literature

4.2. Strengths and Weaknesses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TTS | Time to Surgery |

| EC | Endometrial Cancer |

| DH | Diagnostic hysteroscopy |

| RE-CR | Reggio Emilia Cancer Registry |

References

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today (Version 1.1). Lyon, France. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en/dataviz/tables?mode=population&cancers=24&types=1 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Cancer Research UK Uterine Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/uterine-cancer#heading-Six (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Liu, L.; Habeshian, T.S.; Zhang, J.; Peeri, N.C.; Du, M.; De Vivo, I.; Setiawan, V.W. Differential trends in rising endometrial cancer incidence by age, race, and ethnicity. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7, pkad001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangone, L.; Marinelli, F.; Bisceglia, I.; Braghiroli, M.B.; Mastrofilippo, V.; Pezzarossi, A.; Morabito, F.; Aguzzoli, L.; Mandato, V.D. Optimizing Outcomes through a Multidisciplinary Team Approach in Endometrial Cancer. Healthcare 2023, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdy, H.; Vadakekut, E.S.; Crotzer, D. Endometrial Cancer. 20 April 2024. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fagioli, R.; Vitagliano, A.; Carugno, J.; Castellano, G.; De Angelis, M.C.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A. Hysteroscopy in postmenopause: From diagnosis to the management of intrauterine pathologies. Climacteric 2020, 23, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.W.; Jung, K.W.; Ha, J.; Bae, J. Conditional relative survival of patients with endometrial cancer: A Korean National Cancer Registry study. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 33, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandato, V.D.; Palicelli, A.; Torricelli, F.; Mastrofilippo, V.; Leone, C.; Dicarlo, V.; Tafuni, A.; Santandrea, G.; Annunziata, G.; Generali, M.; et al. Should Endometrial Cancer Treatment Be Centralized? Biology 2022, 11, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy—Ethics, Logistics, and Therapeutics on the Epidemic’s Front Line. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1873–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T. Reduced Cancer Screening Due to Lockdowns of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Reviewing Impacts and Ways to Counteract the Impacts. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 955377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.; Awuah, W.A.; Ng, J.C.; Kundu, M.; Yarlagadda, R.; Sen, M.; Nansubuga, E.P.; Abdul-Rahman, T.; Hasan, M.M. Elective surgeries during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Case burden and physician shortage concerns. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID Surg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: An international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohl, A.E.; Feinglass, J.M.; Shahabi, S.; Simon, M.A. Surgical wait time: A new health indicator in women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 141, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, A.; Percy, C.; Jack, A.; Shanmugaratnam, K.; Sobin, L.; Parkin, D.M.; Whelan, S. International Classification of Disease for Oncology, 3rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mangone, L.; Borciani, E.; Michiara, M.; Sacchettini, C.; Giorgi Rossi, P. I tumori nelle province dell’Area Vasta Emilia Nord: Piacenza, Parma, Reggio Emilia e Modena. Anni 2013–2014. 2015. Available online: https://www.ausl.re.it/WsDocuments/I%20tumori%20nelle%20province%20AVEN,%202013-2014%202%5E.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Vitale, S.G.; Carugno, J.; Riemma, G.; Farkas, Z.; Krasznai, Z.; Bacskó, G.; Lampé, R.; Török, P. The role of hysteroscopy during COVID-19 outbreak: Safeguarding lives and saving resources. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.J.; Wang, J.; Mazuryk, J.; Skinner, S.M.; Meggetto, O.; Ashu, E.; Habbous, S.; Nazeri Rad, N.; Espino-Hernández, G.; Wood, R.; et al. Cancer Care Ontario COVID-19 Impact Working Group. Delivery of Cancer Care in Ontario, Canada, During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022, 5, e228855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, B.E.; Mazuryk, J.; Yermakhanova, O.; Green, B.; Ferguson, S.R.; Kupets, R. Access to Surgery for Endometrial Cancer Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Can. 2024, 46, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algera, M.D.; van Driel, W.J.; Slangen, B.F.M.; Kruitwagen, R.F.P.M.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; Participants of the Dutch Gynecological Oncology Collaborator group. Impact of the COVID-19-pandemic on patients with gynecological malignancies undergoing surgery: A Dutch population-based study using data from the ‘Dutch Gynecological Oncology Audit’. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 165, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogani, G.; Brusadelli, C.; Guerrisi, R.; Lopez, S.; Signorelli, M.; Ditto, A.; Raspagliesi, F. Gynecologic oncology at the time of COVID-19 outbreak. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 31, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotti, F.; Silvagni, A.; Montera, R.; De Cicco Nardone, C.; Luvero, D.; Ficarola, F.; Cundari, G.B.; Branda, F.; Angioli, R.; Terranova, C. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management of Endometrial Cancer: A Monocentric Retrospective Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh-Burgmann, E.J.; Alavi, M.; Schmittdiel, J. Endometrial Cancer Detection During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Obs. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 842–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J.; Quinn, D.; Donnelly, D.W.; McCluggage, W.G.; Coleman, H.G.; Gavin, A.; McMenamin, Ú.C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on endometrial cancer and endometrial hyperplasia diagnoses: A population-based study. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 737–739.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghapanvari, F.; Namdar, P.; Moradi, M.; Yekefallah, L. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 on Hospitalized Patients: A Qualitative Study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2022, 27, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.S.; Agah, S.; Massadeh, M.I.; Valizadeh, M.; Karami, H.; Nejad, A.S. Unraveling the Intricacies of Gut Microbiome, Psychology, and Viral Pandemics: A Holistic Perspective. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, A.S.; Mozaffari Nejad, A.S.; Faraji, H.; Abdel-Moneim, A.S.; Asgari, S.; Karami, H.; Kamali, A.; Kheirkhah Vakilabad, A.A.; Habibi, A.; Faramarzpour, M. Diagnostic Challenges in Fungal Coinfections Associated With Global COVID-19. Scientifica 2025, 2025, 6840605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, A.P.; Seidman, B.C. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the stage of endometrial cancer at diagnosis. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 47, 101191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmullan, J.C.; Leitch, E.; Wilson, S.; Alwahaibi, F.; Ranaghan, L.; Harley, I.J.; Mccomiskey, M.; Craig, E.; Nagar, H.; Dobbs, S. On Behalf Of The N.i Regional Gynae-oncology Multidisciplinary team (mdt). The COVID-19 pandemic’s ripple effects: Investigating the impact of COVID-19 on endometrial cancer in a large UK regional cancer centre. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2024, 45, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, I.; Zaccarelli, E.; Del Grande, M.; Tomao, F.; Multinu, F.; Betella, I.; Ledermann, J.A.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Sessa, C.; Colombo, N. ESMO management and treatment adapted recommendations in the COVID-19 era: Gynaecological malignancies. ESMO Open 2020, 5 (Suppl. S3), e000827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandato, V.D.; Torricelli, F.; Mastrofilippo, V.; Pellegri, C.; Cerullo, L.; Annunziata, G.; Ciarlini, G.; Pirillo, D.; Generali, M.; D’Ippolito, G.; et al. Impact of 2 years of COVID-19 pandemic on ovarian cancer treatment in IRCCS-AUSL of Reggio Emilia. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 163, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedimonte, S.; Li, S.; Laframboise, S.; Ferguson, S.E.; Bernardini, M.Q.; Bouchard-Fortier, G.; Hogen, L.; Cybulska, P.; Worley, M.J., Jr.; May, T. Gynecologic oncology treatment modifications or delays in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in a publicly funded versus privately funded North American tertiary cancer center. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccella, S.; Garzon, S.; Lanzo, G.; Cromi, A.; Zorzato, P.C.; Casarin, J.; Bosco, M.; Porcari, I.; Ciccarone, F.; Malzoni, M.; et al. Practice changes in Italian Gynaecologic Units during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, N.U.; Bilir, E.; Taskin, S.; Vatansever, D.; Dogan, S.; Taskiran, C.; Celik, H.; Ortac, F.; Gungor, M. Perspectives of Gynecologic Oncologists on Minimally Invasive Surgery During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Turkish Society of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Oncology (MIJOD) Survey. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, J.; Farkas, B.; Mastikhina, L.; Flanagan, J.; Skidmore, B.; Salmon, C.; Dixit, D.; Smith, S.; Tsekrekos, S.; Lee, B.; et al. Risk of transmission of respiratory viruses during aerosol-generating medical procedures (AGMPs) revisited in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Antimicrob Resist. Infect. Control. 2022, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seay, K.; Katcher, A.; Hare, M.; Kohn, N.; Juhel, H.; Goldberg, G.L.; Frimer, M. The Impact of Surgical Delay: A Single Institutional Experience at the Epicenter of the COVID Pandemic Treatment Delays in Women with Endometrial Cancer and Endometrial Intraepithelial Hyperplasia. COVID 2024, 4, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHilli, M.M.; Elson, P.; Rybicki, L.; Khorana, A.A.; Rose, P.G. Time to surgery and its impact on survival in patients with endometrial cancer: A National cancer database study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 153, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plubprasit, J.; Sukkasame, P.; Bhamarapravatana, K.; Suwannarurk, K. The Impact of Waiting Time-to-Surgery on Survival in Endometrial Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2024, 25, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 543 | |

| Years of diagnosis | ||

| 2017–2019 | 228 | |

| 2020–2022 | 242 | |

| 2023 | 73 | |

| Age at diagnosis (brackets) | ||

| <40 | 4 | 0.7 |

| 40–64 | 224 | 41.3 |

| ≥65 | 315 | 58.0 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 423 | 77.9 |

| II | 20 | 3.7 |

| III | 53 | 9.8 |

| IV | 20 | 3.7 |

| Unknown | 27 | 5.0 |

| Grade | ||

| G1 | 177 | 32.6 |

| G2 | 200 | 36.8 |

| G3 | 82 | 15.1 |

| Unknown | 84 | 15.5 |

| Diagnostic imaging | ||

| MRI # | 51 | 9.4 |

| CT # | 379 | 69.8 |

| MRI # + CT # | 29 | 5.3 |

| XR # | 29 | 5.3 |

| PET # | 1 | 0.2 |

| Other/unknown | 54 | 9.9 |

| Surgical approach | ||

| Laparotomy | 105 | 19.3 |

| Laparoscopy | 385 | 70.9 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 16 | 3.0 |

| Laparotomy + laparoscopy | 23 | 4.2 |

| Unknown | 14 | 2.6 |

| 2017–2019 | 2020–2022 | 2023 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 228 | 242 | 73 | 543 | |

| Stage | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value | |

| I | 179 (78.5) | 192 (79.3) | 52 (71.2) | 0.66 | 423 |

| II | 8 (3.5) | 8 (3.3) | 4 (5.5) | 0.58 | 20 |

| III | 17 (7.5) | 23 (9.5) | 13 (17.8) | <0.05 | 53 |

| IV | 11 (4.8) | 8 (3.3) | 1 (1.4) | 0.17 | 20 |

| Unknown | 13 (5.7) | 11 (4.6) | 3 (4.1) | — | 27 |

| Grade | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value | |

| G1 | 65 (28.5) | 100 (41.3) | 12 (16.4) | 0.79 | 177 |

| G2 | 93 (40.7) | 73 (30.2) | 34 (46.6) | 0.84 | 200 |

| G3 | 35 (15.4) | 33 (13.6) | 14 (19.2) | 0.70 | 82 |

| Unknown | 35 (15.4) | 36 (14.9) | 13 (17.8) | — | 84 |

| 2017–2019 | 2020–2022 | 2023 | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-Value | n | |

| Number of cases | 228 | 242 | 73 | 543 | |

| Laparotomy | 69 (30.3) | 28 (11.6) | 8 (11.0) | <0.01 | 105 |

| Laparoscopy | 137 (60.1) | 189 (78.1) | 59 (80.8) | <0.05 | 385 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 7 (3.1) | 7 (2.9) | 2 (2.7) | 0.88 | 16 |

| Laparotomy + laparoscopy | 11 (4.8) | 9 (3.7) | 3 (4.1) | 0.66 | 23 |

| Unknown | 4 (1.7) | 9 (3.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0.70 | 14 |

| 2017–2019 | 2020–2022 | 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| TTS, days | 49 (50) | 60 (51) | 74 (98) | |

| TTS, n. cases | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value |

| 1–30 days | 23 (10.1) | 9 (3.7) | 1 (1.4) | <0.01 |

| 31–60 days | 88 (38.6) | 47 (19.4) | 5 (6.9) | <0.01 |

| 61–90 days | 52 (22.8) | 72 (29.8) | 27 (37.0) | <0.05 |

| >90 days | 17 (7.5) | 56 (23.1) | 15 (20.5) | <0.01 |

| Total | 228 | 242 | 73 |

| β | p-Value | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.92 | <0.01 | 0.38; 1.44 |

| Diagnosis period | 22.79 | <0.01 | 14.67; 30.91 |

| Stage | 9.87 | <0.05 | 3.55; 16.19 |

| Age | 0.89 | <0.01 | 0.36; 1.42 |

| 2020–2022 (ref) | 1 | 4.55; 10.12 | |

| 2017–2019 | −19.63 | <0.01 | −31.31; −7.95 |

| 2023 | 31.60 | <0.01 | 13.68; 49.53 |

| Stage I (ref) | 1 | ||

| Stage II | 5.24 | 0.74 | −25.40; 35.87 |

| Stage III | 6.21 | 0.49 | −11.29; 23.71 |

| Stage IV | 48.80 | <0.01 | 23.15; 74.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roncaglia, F.; Mangone, L.; Marinelli, F.; Bisceglia, I.; Braghiroli, M.B.; Mastrofilippo, V.; Morabito, F.; Magnani, A.; Neri, A.; Aguzzoli, L.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the Stage and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: A Cancer Registry Analysis from an Italian Comprehensive Cancer Center. Cancers 2025, 17, 2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162686

Roncaglia F, Mangone L, Marinelli F, Bisceglia I, Braghiroli MB, Mastrofilippo V, Morabito F, Magnani A, Neri A, Aguzzoli L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the Stage and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: A Cancer Registry Analysis from an Italian Comprehensive Cancer Center. Cancers. 2025; 17(16):2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162686

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoncaglia, Francesca, Lucia Mangone, Francesco Marinelli, Isabella Bisceglia, Maria Barbara Braghiroli, Valentina Mastrofilippo, Fortunato Morabito, Antonia Magnani, Antonino Neri, Lorenzo Aguzzoli, and et al. 2025. "Impact of COVID-19 on the Stage and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: A Cancer Registry Analysis from an Italian Comprehensive Cancer Center" Cancers 17, no. 16: 2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162686

APA StyleRoncaglia, F., Mangone, L., Marinelli, F., Bisceglia, I., Braghiroli, M. B., Mastrofilippo, V., Morabito, F., Magnani, A., Neri, A., Aguzzoli, L., & Mandato, V. D. (2025). Impact of COVID-19 on the Stage and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer: A Cancer Registry Analysis from an Italian Comprehensive Cancer Center. Cancers, 17(16), 2686. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17162686