Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement and Reporting for Patients with Soft Tissue Tumors: A Scoping Literature Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

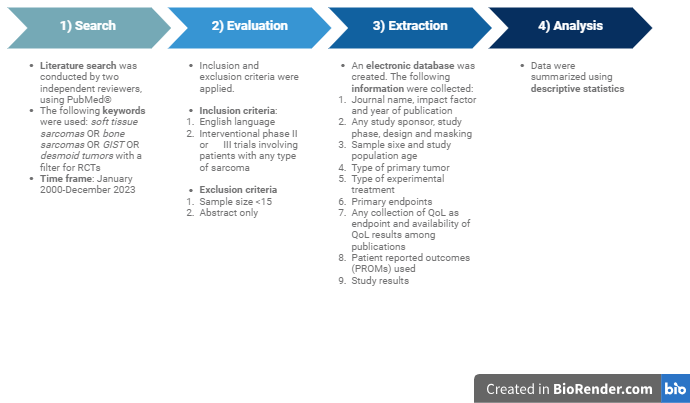

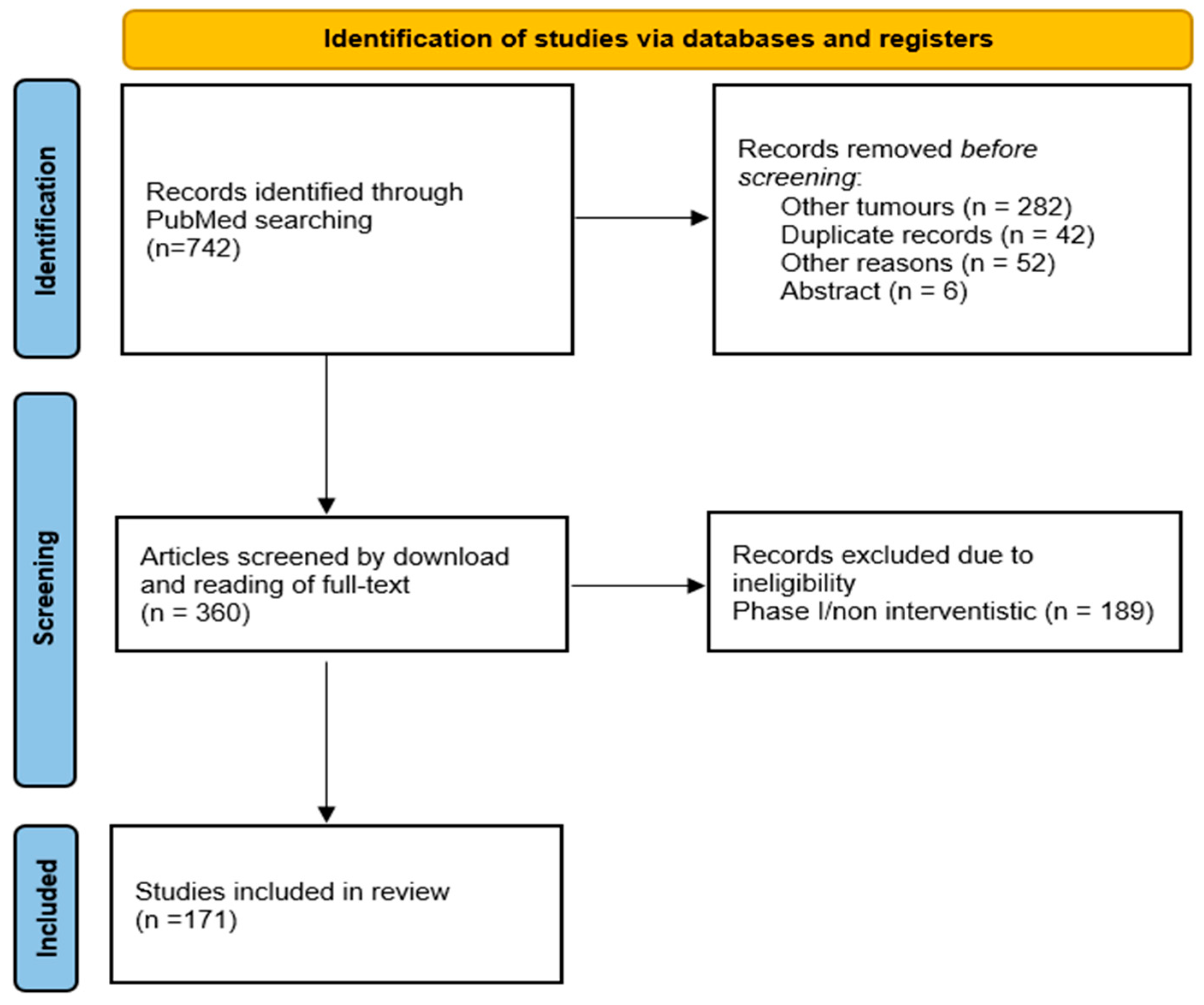

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

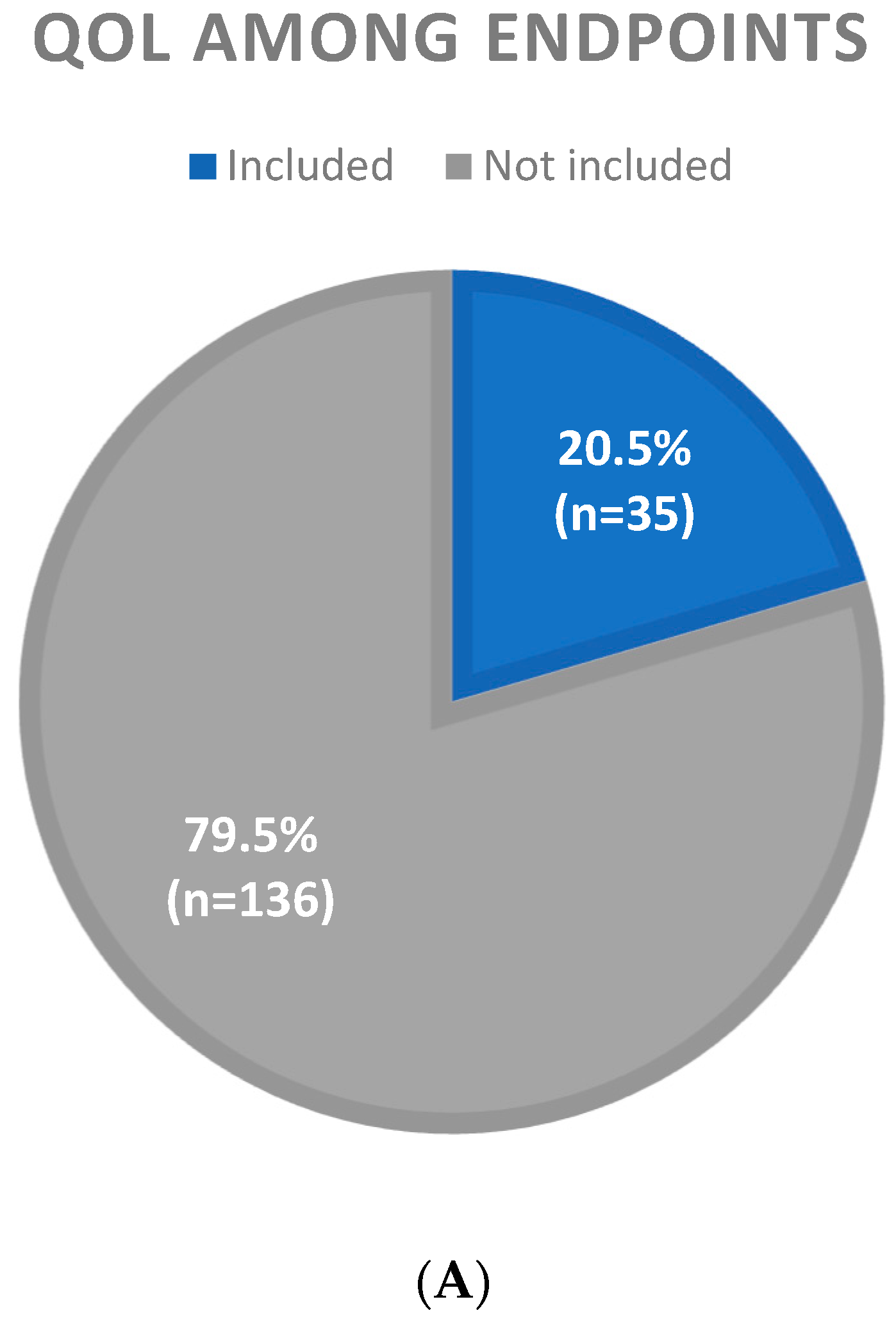

3.2. Inclusion of QoL Among Study Endpoints

3.3. Presence of QoL Results in Primary and Secondary Publications

3.4. QoL Methodology

4. Discussion

Strenghts and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blay, J.Y.; Hindi, N.; Bollard, J.; Aguiar, S., Jr.; Angel, M.; Araya, B.; Badilla, R.; Bernabeu, D.; Campos, F.; Caro-Sánchez, C.H.S.; et al. SELNET clinical practice guidelines for soft tissue sarcoma and GIST. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 102, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronchi, A.; Miah, A.B.; Dei Tos, A.P.; Abecassis, N.; Bajpai, J.; Bauer, S.; Biagini, R.; Bielack, S.; Blay, J.Y.; Bolle, S.; et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up☆. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1348–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwirth, M.G.; Song, Y.; Sinnamon, A.J.; Fraker, D.L.; Zager, J.S.; Karakousis, G.C. Isolated Limb Perfusion and Infusion for Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma: A Contemporary Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 3803–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Reflection Paper on the Use of Patient-Reported Outcome Measure in Oncology Studies. 17 June 2014. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/06/WC500168852.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Soomers, V.; Husson, O.; Young, R.; Desar, I.; Van der Graaf, W. The sarcoma diagnostic interval: A systematic review on length, contributing factors and patient outcomes. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Traub, F.; Griffin, A.M.; Wunder, J.S.; Ferguson, P.C. Influence of unplanned excisions on the outcomes of patients with stage III extremity soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2018, 124, 3868–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italiano, A.; Mathoulin-Pelissier, S.; Cesne, A.L.; Terrier, P.; Bonvalot, S.; Collin, F.; Michels, J.J.; Blay, J.Y.; Coindre, J.M.; Bui, B. Trends in survival for patients with metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2011, 117, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, G.; Terrenato, I.; Giacomelli, L.; Zoccali, C.; Condoleo, M.F.; Falcicchio, C.; Baldi, J.; Vari, S.; Ferraresi, V.; Biagini, R.; et al. Sarcoma patients’ quality of life from diagnosis to yearly follow-up: Experience from an Italian tertiary care center. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 3125–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnette, R.; Hess, L.M.; Nicol, S.J.; Tai, D.F.; Copley-Merriman, C. The Patient Experience with Soft Tissue Sarcoma: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Patient 2017, 10, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Ries, A.L. Quality of life: Concept and definition. COPD 2007, 4, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maio, M.; Basch, E.; Bryce, J.; Perrone, F. Patient-reported outcomes in the evaluation of toxicity of anticancer treatments. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims: Draft guidance. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Graaf, W.T.; Blay, J.Y.; Chawla, S.P.; Kim, D.W.; Bui-Nguyen, B.; Casali, P.G.; Schöffski, P.; Aglietta, M.; Staddon, A.P.; Beppu, Y.; et al. EORTC Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group; PALETTE study group. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012, 379, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetri, G.D.; Reichardt, P.; Kang, Y.-K.; Blay, J.-Y.; Rutkowski, P.; Gelderblom, H.; Hohenberger, P.; Leahy, M.; Von Mehren, M.; Joensuu, H.; et al. GRID study investigators. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetri, G.D.; von Mehren, M.; Jones, R.L.; Hensley, M.L.; Schuetze, S.M.; Staddon, A.; Milhem, M.; Elias, A.; Ganjoo, K.; Tawbi, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Trabectedin or Dacarbazine for Metastatic Liposarcoma or Leiomyosarcoma After Failure of Conventional Chemotherapy: Results of a Phase III Randomized Multicenter Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöffski, P.; Chawla, S.; Maki, R.G.; Italiano, A.; Gelderblom, H.; Choy, E.; Grignani, G.; Camargo, V.; Bauer, S.; Rha, S.Y.; et al. Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tap, W.D.; Gelderblom, H.; Palmerini, E.; Desai, J.; Bauer, S.; Blay, J.-Y.; Alcindor, T.; Ganjoo, K.; Martín-Broto, J.; Ryan, C.W.; et al. Pexidartinib versus placebo for advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumour (ENLIVEN): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay, J.Y.; Serrano, C.; Heinrich, M.C.; Zalcberg, J.; Bauer, S.; Gelderblom, H.; Schöffski, P.; Jones, R.L.; Attia, S.; d’Amato, G.; et al. Ripretinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours (INVICTUS): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, M.; Ratan, R.; Alcindor, T.; Schöffski, P.; Van Der Graaf, W.T.; Wilky, B.A.; Riedel, R.F.; Lim, A.; Smith, L.M.; Moody, S.; et al. Nirogacestat, a γ-Secretase Inhibitor for Desmoid Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coens, C.; van der Graaf, W.T.; Blay, J.Y.; Chawla, S.P.; Judson, I.; Sanfilippo, R.; Manson, S.C.; Hodge, R.A.; Marreaud, S.; Prins, J.B.; et al. Health-related quality-of-life results from PALETTE: A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of pazopanib versus placebo in patients with soft tissue sarcoma whose disease has progressed during or after prior chemotherapy-a European Organization for research and treatment of cancer soft tissue and bone sarcoma group global network study (EORTC 62072). Cancer 2015, 121, 2933–2941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karch, A.; Koch, A.; Grünwald, V. A phase II trial comparing pazopanib with doxorubicin as first-line treatment in elderly patients with metastatic or advanced soft tissue sarcoma (EPAZ): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016, 17, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudgens, S.; Forsythe, A.; Kontoudis, I.; D’Adamo, D.; Bird, A.; Gelderblom, H. Evaluation of Quality of Life at Progression in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Sarcoma 2017, 2017, 2372135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gough, N.J.; Smith, C.; Ross, J.R.; Riley, J.; Judson, I. Symptom burden, survival and palliative care in advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcoma 2011, 2011, 325189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McDonough, J.; Eliott, J.; Neuhaus, S.; Reid, J.; Butow, P. Health-related quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and unmet health needs in patients with sarcoma: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Naci, H.; Gurpinar, E.; Poplavska, E.; Pinto, A.; Aggarwal, A. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: Retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009-13. BMJ 2017, 359, j4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, M.; Perrone, F. Lessons from clinical trials on quality-of-life assessment in ovarian cancer trials. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallowfield, L.J. Quality of life assessment using patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures: Still a Cinderella outcome? Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 2286–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maio, M.; Gallo, C.; Leighl, N.B.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Daniele, G.; Nuzzo, F.; Gridelli, C.; Gebbia, V.; Ciardiello, F.; De Placido, S.; et al. Symptomatic toxicities experienced during anticancer treatment: Agreement between patient and physician reporting in three randomized trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, M.; Singer, S.; Hentschel, L.; Richter, S.; Hohenberger, P.; Kasper, B.; Andreou, D.; Pink, D.; Jakob, J.; Grützmann, R.; et al. The association of Health-Related Quality of Life and 1-year-survival in sarcoma patients—Results of a Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa). Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2000–2014 n = 77 (45.0%) | 2015–2023 n = 94 (55.0%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Study sponsor | ||

| Academic | 52 (67.5%) | 56 (59.6%) |

| Industry sponsored | 25 (32.5%) | 38 (40.4%) |

| Study phase | ||

| II | 44 (57.1%) | 48 (51.1%) |

| III | 33 (42.9%) | 46 (48.9%) |

| Study design | ||

| Superiority | 57 (74.0%) | 68 (72.3%) |

| Non comparative | 12 (15.6%) | 14 (14.9%) |

| Non inferiority | 5 (6.5%) | 6 (6.4%) |

| Equivalence | 3 (3.9%) | 6 (6.4%) |

| Masking | ||

| Open label | 64 (83.1%) | 72 (76.6%) |

| Blinded | 13 (16.9%) | 22 (23.4%) |

| Tumor type | ||

| Soft tissue sarcomas | 38 (49.3%) | 56 (59.6%) |

| GIST | 11 (14.3%) | 10 (10.5%) |

| Bone sarcomas | 6 (7.8%) | 12 (12.9%) |

| Soft tissue + bone sarcomas | 4 (5.2%) | 8 (8.5%) |

| Desmoid tumor | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (4.2%) |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 18 (23.4%) | 3 (3.2%) |

| Tenosynovial giant cell tumor | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) |

| Disease setting | ||

| Palliative | 51 (66.2%) | 72 (76.6%) |

| Adjuvant/Neoadjuvant | 26 (33.8%) | 22 (23.4%) |

| Experimental treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 47 (64.0%) | 38 (40.4%) |

| Targeted therapy | 15 (19.5%) | 44 (46.8%) |

| Immunotherapy | 1 (1.3%) | 7 (7.5%) |

| Radiotherapy | 5 (6.5%) | 3 (3.2%) |

| Other | 9 (11.7%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| Primary endpoint | ||

| PFS/DFS | 22 (28.6%) | 47 (50.0%) |

| Tumor response | 25 (32.5%) | 16 (17.0%) |

| OS | 14 (18.1%) | 7 (7.5%) |

| EFS | 5 (6.5%) | 13 (13.8%) |

| Other | 11 (14.3%) | 11 (11.7%) |

| Study results (primary endpoint) | ||

| Positive | 43 (55.8%) | 52 (55.3%) |

| Negative | 34 (44.2%) | 42 (44.7%) |

| QoL Not Included n = 136 (79.5%) | QoL Included n = 35 (20.5%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Year of primary manuscript | ||

| 2000–2014 | 64 (83.1%) | 13 (16.9%) |

| 2015–2023 | 72 (76.6%) | 22 (23.4%) |

| Study sponsor | ||

| Academic | 94 (87.0%) | 14 (13.0%) |

| Industry sponsored | 42 (66.6%) | 21 (33.4%) |

| Study phase | ||

| II | 77 (83.7%) | 15 (16.3%) |

| III | 59 (74.7%) | 20 (25.3%) |

| Study design | ||

| Superiority | 98 (78.4%) | 27 (21.6%) |

| Non comparative | 20 (87.0%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Non inferiority | 9 (81.8%) | 2 (18.2%) |

| Equivalence | 6 (66.6%) | 3 (33.4%) |

| Masking | ||

| Open label | 112 (82.3%) | 24 (17.7%) |

| Blinded | 24 (68.6%) | 11 (31.4%) |

| Tumor type | ||

| Soft tissue sarcomas | 78 (83.0%) | 16 (17.0%) |

| Bone sarcomas | 17 (94.4%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| GIST | 15 (71.4%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 13 (61.9%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| Soft tissue + bone sarcomas | 12 (100%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Desmoid tumor | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) |

| Tenosynovial giant cell tumor | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Disease setting | ||

| Palliative | 93 (75.6%) | 30 (24.4%) |

| Adjuvant/Neoadjuvant | 43 (89.6%) | 5 (10.4%) |

| Experimental treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 71 (83.5%) | 14 (16.5%) |

| Targeted therapy | 43 (72.9%) | 16 (27.1%) |

| Immunotherapy | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Radiotherapy | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Other | 10 (90.9%) | 1 (9.1%) |

| Primary endpoint | ||

| PFS/DFS | 51 (73.9%) | 18 (26.1%) |

| Tumor response | 36 (87.8%) | 5 (12.2%) |

| OS | 16 (76.2%) | 5 (23.9%) |

| EFS | 17 (94.4%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Other | 16 (72.7%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| Study results (primary endpoint) | ||

| Positive | 70 (73.7%) | 25 (26.3%) |

| Negative | 65 (86.6%) | 10 (13.4%) |

| Author/Year | Disease | Experimental Treatment | Control Treatment | Primary Endpoint | QoL Endpoint | QoL Methodology | QoL Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van der Graaf WTA et al., 2012 [14] | STS | Pazopanib | Placebo | PFS | Secondary | EORTC QLQ- C30, EQ-5D, Global Heath status/quality-of-life score | Primary and secondary publication |

| Demetri GD et al., 2013 [15] | GIST | Regorafenib | Placebo | PFS | Exploratory | EORTC QLQ-C30, EQ-5D | Secondary publication |

| Demetri GD et al., 2016 [16] | STS | Trabectedin | Dacarbazin | OS | Secondary | M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) | Secondary publication |

| Shoffski P et al., 2016 [17] | STS | Eribulin | Dacarbazin | OS | Exploratory | EORTC QLQ-C30, EQ-5D | Secondary publication |

| Tap WT et al., 2019 [18] | TGCT | Pexidartinib | Placebo | Tumor response | Secondary | PROMIS, stiffness, Brief Pain Inventory, Pain-30 | Primary and secondary publication |

| Blay JY et al., 2020 [19] | GIST | Ripretinib | Placebo | OS | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30, EQ-5D-5L, EQ-VAS | Primary and secondary publication |

| Gounder M. et al., 2023 [20] | Desmoid Tumor | Nirogacestat | Placebo | PFS | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30, Brief Pain Inventory, GODDESS, DTSS, DTIS | Primary and secondary publication |

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Type of PROMs | |

| Generic | 28 (80%) |

| Disease specific (all in Kaposi Sarcoma) | 4 (11.4%) |

| Both generic and disease specific (1 in KS, 1 in STS, 1 in desmoid tumor) | 3 (8.6%) |

| QoL questionnaire (not mutually exclusive) | |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | 22 (62.9%) |

| EQ-5D | 7 (20%) |

| mBPI short form | 5 (14.3%) |

| EQ-VAS | 2 (5.7%) |

| Other tools | 18 (51.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazzocca, A.; Paternostro, F.; Garofalo, S.; Silletta, M.; Romandini, D.; Orlando, S.; Risi Ambrogioni, L.; Gorgone, P.; Tonini, G.; Vincenzi, B. Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement and Reporting for Patients with Soft Tissue Tumors: A Scoping Literature Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17142280

Mazzocca A, Paternostro F, Garofalo S, Silletta M, Romandini D, Orlando S, Risi Ambrogioni L, Gorgone P, Tonini G, Vincenzi B. Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement and Reporting for Patients with Soft Tissue Tumors: A Scoping Literature Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(14):2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17142280

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazzocca, Alessandro, Flavia Paternostro, Serena Garofalo, Marianna Silletta, Davide Romandini, Sarah Orlando, Laura Risi Ambrogioni, Pierangelo Gorgone, Giuseppe Tonini, and Bruno Vincenzi. 2025. "Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement and Reporting for Patients with Soft Tissue Tumors: A Scoping Literature Review" Cancers 17, no. 14: 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17142280

APA StyleMazzocca, A., Paternostro, F., Garofalo, S., Silletta, M., Romandini, D., Orlando, S., Risi Ambrogioni, L., Gorgone, P., Tonini, G., & Vincenzi, B. (2025). Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement and Reporting for Patients with Soft Tissue Tumors: A Scoping Literature Review. Cancers, 17(14), 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17142280