Which Clinical Factors Are Associated with the Post-Denosumab Size Reduction of Giant Cell Tumors? The Korean Society of Spinal Tumor (KSST) Multicenter Study 2023-02

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

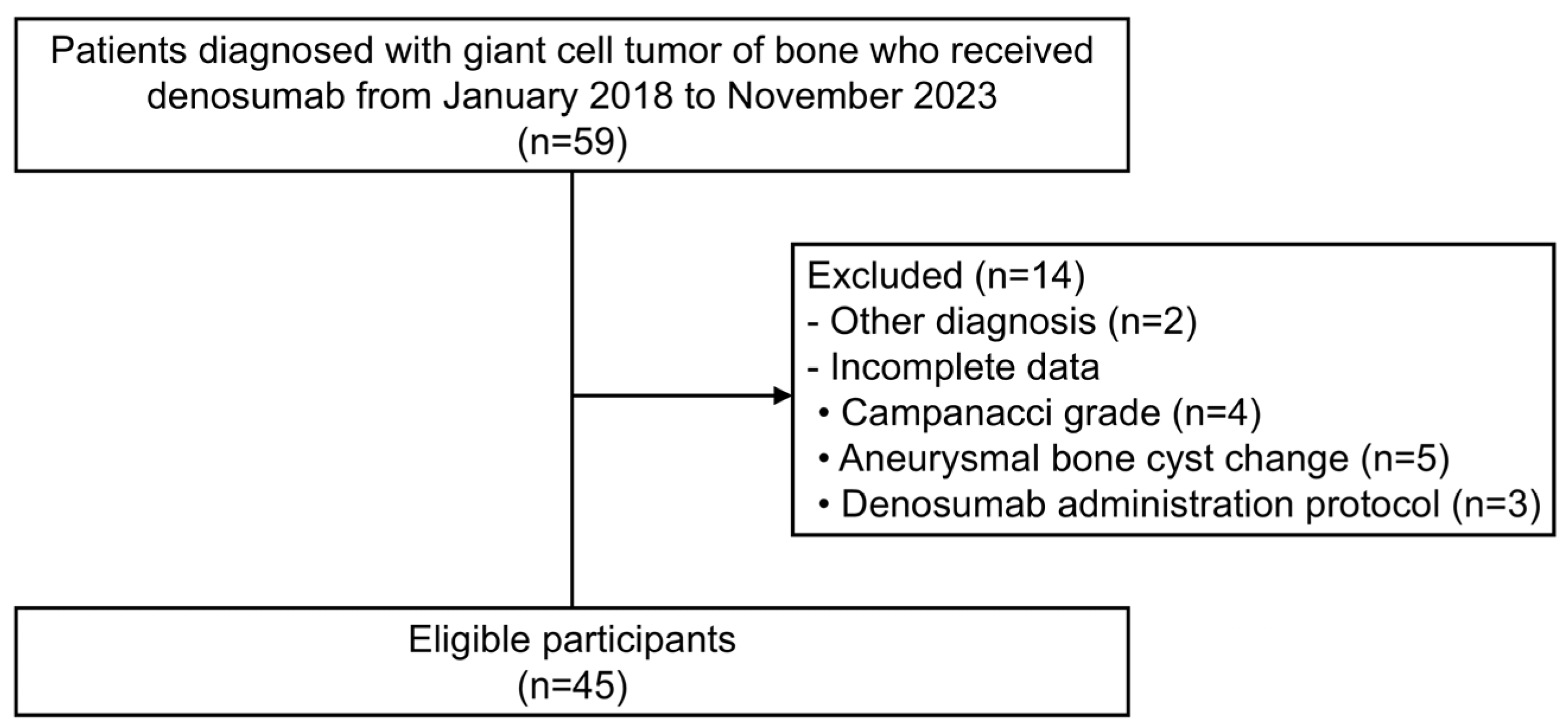

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables and Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Predictive Factors of Tumor Size Reduction in All Patients

3.2. Subgroup Analyses on Predictive Factors by Lesion Location

3.3. Subgroup Analyses of Predictive Factors by Recurrence Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, Y.; Nizami, S.; Goto, H.; Lee, F.Y. Modern interpretation of giant cell tumor of bone: Predominantly osteoclastogenic stromal tumor. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2012, 4, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, M.W.; Cho, Y.J. Current Issues on Denosumab Use in Giant Cell Tumor of Bone. J. Korean Orthop. Assoc. 2023, 58, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinder, P.S.; Hindiskere, S.; Doddarangappa, S.; Pal, U. Evaluation of Local Recurrence in Giant-Cell Tumor of Bone Treated by Neoadjuvant Denosumab. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 11, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanacci, M.; Baldini, N.; Boriani, S.; Sudanese, A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1987, 69, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Lee, K.-W.; Lee, J.S. Surgical Treatment of Recurrent Giant Cell Tumor Occurring at the First Metatarsal. J. Korean Orthop. Assoc. 2019, 54, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, T.; Morioka, H.; Nishida, Y.; Kakunaga, S.; Tsuchiya, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Asami, Y.; Inoue, T.; Yoneda, T. Objective tumor response to denosumab in patients with giant cell tumor of bone: A multicenter phase II trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engellau, J.; Seeger, L.; Grimer, R.; Henshaw, R.; Gelderblom, H.; Choy, E.; Chawla, S.; Reichardt, P.; O’Neal, M.; Feng, A.; et al. Assessment of denosumab treatment effects and imaging response in patients with giant cell tumor of bone. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Sun, W.; Li, S. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid in cases of surgically unsalvageable giant cell tumor of bone: A randomized clinical trial. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 35, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Available online: https://recist.eortc.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Young, H.; Baum, R.; Cremerius, U.; Herholz, K.; Hoekstra, O.; Lammertsma, A.A.; Pruim, J.; Price, P. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: Review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur. J. Cancer 1999, 35, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Charnsangavej, C.; Faria, S.C.; Macapinlac, H.A.; Burgess, M.A.; Patel, S.R.; Chen, L.L.; Podoloff, D.A.; Benjamin, R.S. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: Proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.I.; Turin, T.C. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindiskere, S.; Errani, C.; Doddarangappa, S.; Ramaswamy, V.; Rai, M.; Chinder, P.S. Is a Short-course of Preoperative Denosumab as Effective as Prolonged Therapy for Giant Cell Tumor of Bone? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020, 478, 2522–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakarun, C.J.; Forrester, D.M.; Gottsegen, C.J.; Patel, D.B.; White, E.A.; Matcuk, G.R., Jr. Giant cell tumor of bone: Review, mimics, and new developments in treatment. Radiographics 2013, 33, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, D.A.; Adachi, J.D.; Bell, A.; Brown, V. Denosumab: Mechanism of action and clinical outcomes. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, A.; Price, P.M. Early tumor drug pharmacokinetics is influenced by tumor perfusion but not plasma drug exposure. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 8184–8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errani, C.; Tsukamoto, S.; Leone, G.; Righi, A.; Akahane, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Donati, D.M. Denosumab May Increase the Risk of Local Recurrence in Patients with Giant-Cell Tumor of Bone Treated with Curettage. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2018, 100, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmerini, E.; Seeger, L.L.; Gambarotti, M.; Righi, A.; Reichardt, P.; Bukata, S.; Blay, J.-Y.; Dai, T.; Jandial, D.; Picci, P. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone: Analysis of an open-label phase 2 study of denosumab. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Overall Cohort, n (%) | Proportional Lesion Shrinkage, n (%) | Absolute Lesion Shrinkage, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 45) | ≥5% (n = 19) | <5% (n = 26) | ≥5 mm (n = 15) | <5 mm (n = 30) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 16 (35.6) | 4 (25) | 12 (75) | 4 (25) | 12 (75) |

| Female | 29 (64.4) | 15 (51.7) | 14 (48.3) | 11 (37.9) | 18 (62.1) |

| Age, years | |||||

| <40 | 27 (60) | 12 (44.4) | 15 (55.6) | 9 (33.3) | 18 (66.7) |

| ≥40 | 18 (40) | 7 (38.9) | 11 (61.1) | 6 (33.3) | 12 (66.7) |

| Lesion location | |||||

| Extremities | 25 (55.6) | 9 (36) | 16 (64) | 8 (32) | 17 (68) |

| Spine/pelvis | 20 (44.4) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | 7 (35) | 13 (65) |

| Campanacci grade | |||||

| I | 3 (6.7) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) |

| II | 17 (37.8) | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) |

| III | 25 (55.6) | 15 (60) | 10 (40) | 12 (48) | 13 (52) |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst-like change | |||||

| Yes | 15 (33.3) | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) |

| No | 30 (66.7) | 11 (36.7) | 19 (63.3) | 7 (23.3) | 23 (76.7) |

| Recurrence status | |||||

| Primary | 35 (77.8) | 14 (40) | 21 (60) | 10 (28.6) | 25 (71.4) |

| Recurrent | 10 (22.2) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Extraosseous extension | |||||

| Yes | 27 (60) | 14 (51.9) | 13 (48.1) | 11 (40.7) | 16 (59.3) |

| No | 18 (40) | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 4 (22.2) | 14 (77.8) |

| Denosumab protocol compliance | |||||

| standard | 30 (66.7) | 13 (43.3) | 17 (56.7) | 12 (40) | 18 (60) |

| non-standard | 15 (33.3) | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 3 (20) | 12 (80) |

| Total injection number, times | |||||

| <5 | 17 (37.8) | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | 3 (17.6) | 14 (82.4) |

| ≥5 | 28 (62.2) | 15 (53.6) | 13 (46.4) | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) |

| The longest tumor diameter, cm | |||||

| <5 | 23 (51.1) | 8 (35.8) | 15 (65.2) | 5 (21.7) | 18 (78.3) |

| ≥5 and <7 | 9 (20) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) |

| ≥7 | 13 (28.9) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) |

| Factors | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5% | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5 mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 3.214 (0.837–12.346) | 0.089 | 3.023 (0.699–13.073) | 0.139 | 1.833 (0.472–7.126) | 0.382 | ||

| Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years) | 1.258 (0.373–4.237) | 0.712 | 1.0 (0.282–3.544) | 1.000 | ||||

| Lesion location (Spine/pelvis vs. Extremities) | 1.776 (0.536–5.882) | 0.347 | 1.144 (0.329–3.968) | 0.832 | ||||

| Campanacci Grade (III vs. I + II) | 6.0 (1.545–23.3) | 0.010 | 4.819 (1.121–20.714) | 0.035 * | 5.231 (1.219–22.45) | 0.026 | 2.58 (0.426–15.626) | 0.303 |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst-like change (Yes vs. No) | 1.974 (0.562–6.939) | 0.289 | 3.755 (1.002–14.07) | 0.050 | 8.734 (1.159–65.845) | 0.035 * | ||

| Recurrence status (Recurrent vs. Primary) | 1.5 (0.365–6.157) | 0.574 | 2.5 (0.592–10.555) | 0.212 | ||||

| Extraosseous extension (Yes vs. No) | 2.8 (0.78–10.052) | 0.114 | 2.406 (0.623–9.287) | 0.203 | ||||

| Denosumab protocol compliance (standard vs. non-standard) | 1.147 (0.325–4.045) | 0.831 | 2.667 (0.619–11.493) | 0.188 | ||||

| Number of denosumab injections (≥5 times vs. <5 times) | 4.242 (0.935–19.256) | 0.054 | 2.27 (0.511–10.08) | 0.281 | 3.5 (0.817–14.986) | 0.091 | 3.249 (0.514–20.555) | 0.211 |

| The longest tumor diameter (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 3.055 (0.804–11.6) | 0.304 | 3.0 (0.819–10.991) | 0.097 | 0.889 (0.106–7.477) | 0.914 | ||

| The longest tumor diameter (≥7 cm vs. <7 cm) | 3.055 (0.804–11.6) | 0.101 | 5.714 (1.414–23.097) | 0.014 | 12.380 (1.038–147.694) | 0.047 * | ||

| Factors | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5% | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5 mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 2 (0.366–10.919) | 0.423 | 1.481 (0.265–8.267) | 0.654 | ||||

| Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years) | 2 (0.366–10.919) | 0.423 | 1.481 (0.265–8.267) | 0.654 | ||||

| Campanacci Grade (III vs. I + II) | 13.333 (1.321–134.615) | 0.028 | 11.171 (1.023–122.014) | 0.048 * | 10 (0.995–100.462) | 0.050 | 4.912 (0.404–59.7) | 0.212 |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst-like change (Yes vs. No) | 3.333 (0.599–18.543) | 0.169 | 5.5 (0.836–36.198) | 0.076 | 3.291 (0.402–26.926) | 0.267 | ||

| Recurrence status (Recurrent vs. Primary) | 7.5 (0.645–87.193) | 0.107 | 9.6 (0.807–114.173) | 0.073 | 4.168 (0.286–60.727) | 0.296 | ||

| Extraosseous extension (Yes vs. No) | 10.286 (1.030–102.753) | 0.047 | 7.875 (0.788–78.671) | 0.079 | ||||

| Denosumab protocol compliance (standard vs. non-standard) | 1.591 (0.239–10.572) | 0.631 | 1.25 (0.185–8.444) | 0.819 | ||||

| Number of denosumab injections (≥5 times vs. <5 times) | 5.833 (0.900–37.818) | 0.064 | 4.573 (0.577–36.230) | 0.150 | 4.286 (0.661–27.785) | 0.127 | ||

| The longest tumor diameter (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1.333 (0.254–7.007) | 0.734 | 1.833 (0.333–10.095) | 0.486 | ||||

| The longest tumor diameter (≥7 cm vs. <7 cm) | 2 (0.231–17.338) | 0.529 | 2.5 (0.284–22.042) | 0.409 | ||||

| Factors | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5% | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5 mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 6 (0.532–67.649) | 0.147 | 2.667 (0.237–30.066) | 0.427 |

| Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years) | 1.556 (0.244–9.913) | 0.640 | 1.687 (0.251–11.336) | 0.590 |

| Campanacci Grade (III vs. I + II) | 3.5 (0.549–22.304) | 0.185 | 2.917 (0.407–20.899) | 0.407 |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst-like change (Yes vs. No) | 2.25 (0.170–29.767) | 0.538 | 4.8 (0.35–65.758) | 0.24 |

| Recurrence status (Primary vs. Recurrent) | 2.667 (0.361–19.608) | 0.337 | 1.11 (0.148–8.333) | 0.919 |

| Extraosseous extension (Yes vs. No) | 1 (0.167–5.985) | 1.000 | 0.833 (0.129–5.396) | 0.848 |

| Denosumab Protocol Compliance (standard vs. non-standard) | 1 (0.167–5.985) | 1.000 | 7 (0.647–75.735) | 0.109 |

| Number of denosumab injections (≥5 times vs. <5 times) | 1.714 (0.219–13.406) | 0.608 | 2.667 (0.237–30.066) | 0.427 |

| The longest tumor diameter (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 2.333 (0.373–14.613) | 0.365 | 7 (0.647–75.735) | 0.109 |

| The longest tumor diameter (≥7 cm vs. <7 cm) | 3.5 (0.549–22.304) | 0.185 | 20 (1.676–238.63) | 0.018 * |

| Factors | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5% | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5 mm | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 1.875 (0.441–7.963) | 0.394 | 0.844 (0.185–3.804) | 0.825 | ||||

| Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years) | 1.538 (0.359–6.579) | 0.562 | 1.4 (0.287–6.849) | 0.677 | ||||

| Lesion location (Spine/pelvis vs. Extremities) | 3.333 (0.806–13.699) | 0.097 | 4 (0.817–19.608) | 0.087 | 1.776 (0.403–7.874) | 0.447 | ||

| Campanacci Grade (III vs. I + II) | 5 (1.147–21.796) | 0.032 | 5.781 (1.181–28.297) | 0.030 * | 3.5 (0.727–16.848) | 0.118 | ||

| Aneurysmal bone cyst-like change (Yes vs. No) | 1.778 (0.403–7.844) | 0.447 | 4 (0.824–19.423) | 0.086 | 11.936 (1.074–132.69) | 0.044 * | ||

| Extraosseous extension (Yes vs. No) | 2.75 (0.651–11.624) | 0.169 | 2.154 (0.451–10.287) | 0.336 | ||||

| Denosumab protocol compliance (standard vs. non-standard) | 1.538 (0.359–6.599) | 0.562 | 7.071 (0.774–64.575) | 0.083 | 4.15 (0.353–48.761) | 0.258 | ||

| Number of denosumab injections (≥5 times vs. <5 times) | 2.75 (0.651–11.624) | 0.169 | 2.154 (0.451–10.287) | 0.336 | ||||

| The longest tumor diameter (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 2.167 (0.547–8.586) | 0.271 | 4.148 (0.854–20.138) | 0.078 | 1.231 (0.071–21.454) | 0.887 | ||

| The longest tumor diameter (≥7 cm vs. <7 cm) | 3.187 (0.698–14.557) | 0.135 | 7.875 (1.503–41.271) | 0.015 | 12.461 (0.496–313.261) | 0.125 | ||

| Factors | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5% | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5 mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | NE | 0.999 | NE | 0.999 |

| Age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years) | 1 (0.080–12.557) | 1.000 | 1 (0.08–12.557) | 1.000 |

| Lesion location (Extremities vs. Spine/Pelvis) | 6 (0.354–101.568) | 0.214 | 6 (0.354–101.568) | 0.214 |

| Campanacci Grade (III vs. I + II) | NE | 0.999 | NE | 0.999 |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst-like change (Yes vs. No) | 2.25 (0.179–28.254) | 0.530 | 2.25 (0.179–28.254) | 0.530 |

| Extraosseous extension (Yes vs. No) | 2.667 (0.158–45.141) | 0.497 | 2.667 (0.158–45.141) | 0.497 |

| Denosumab protocol compliance (non-standard vs. standard) | 0.375 (0.022–6.348) | 0.497 | 0.375 (0.022–6.348) | 0.497 |

| Number of denosumab injections (≥5 times vs. <5 times) | NE | 0.999 | NE | 0.999 |

| The longest tumor diameter (≥5 cm vs. <5 cm) | 1 (0.08–12.557) | 1.000 | 1 (0.08–12.557) | 1.000 |

| The longest tumor diameter (≥7 cm vs. <7 cm) | 2.667 (0.158–45.141) | 0.497 | 2.667 (0.158–45.141) | 0.497 |

| Factors | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5% | Lesion Shrinkage of ≥5 mm |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | Campanacci grade III | ABC-like change The longest diameter ≥7 cm |

| Subgroup by lesion location | ||

| Extremities | Campanacci grade III | |

| Spine/pelvis | The longest diameter ≥7 cm | |

| Subgroup by recurrence status | ||

| Primary | Campanacci grade III | ABC-like change |

| Recurrent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joo, M.W.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, W.; Kim, Y.; Cho, J.H.; Bernthal, N.M.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.-S. Which Clinical Factors Are Associated with the Post-Denosumab Size Reduction of Giant Cell Tumors? The Korean Society of Spinal Tumor (KSST) Multicenter Study 2023-02. Cancers 2025, 17, 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132121

Joo MW, Park S-J, Kim W, Kim Y, Cho JH, Bernthal NM, Lee M, Lee J, Lee Y-S. Which Clinical Factors Are Associated with the Post-Denosumab Size Reduction of Giant Cell Tumors? The Korean Society of Spinal Tumor (KSST) Multicenter Study 2023-02. Cancers. 2025; 17(13):2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132121

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoo, Min Wook, Se-Jun Park, Wanlim Kim, Yongsung Kim, Jae Hwan Cho, Nicholas Matthew Bernthal, Minpyo Lee, Jewoo Lee, and Yong-Suk Lee. 2025. "Which Clinical Factors Are Associated with the Post-Denosumab Size Reduction of Giant Cell Tumors? The Korean Society of Spinal Tumor (KSST) Multicenter Study 2023-02" Cancers 17, no. 13: 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132121

APA StyleJoo, M. W., Park, S.-J., Kim, W., Kim, Y., Cho, J. H., Bernthal, N. M., Lee, M., Lee, J., & Lee, Y.-S. (2025). Which Clinical Factors Are Associated with the Post-Denosumab Size Reduction of Giant Cell Tumors? The Korean Society of Spinal Tumor (KSST) Multicenter Study 2023-02. Cancers, 17(13), 2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132121