Visceral Angiosarcoma: A Nationwide Population-Based Study from 2000–2017

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Treatment

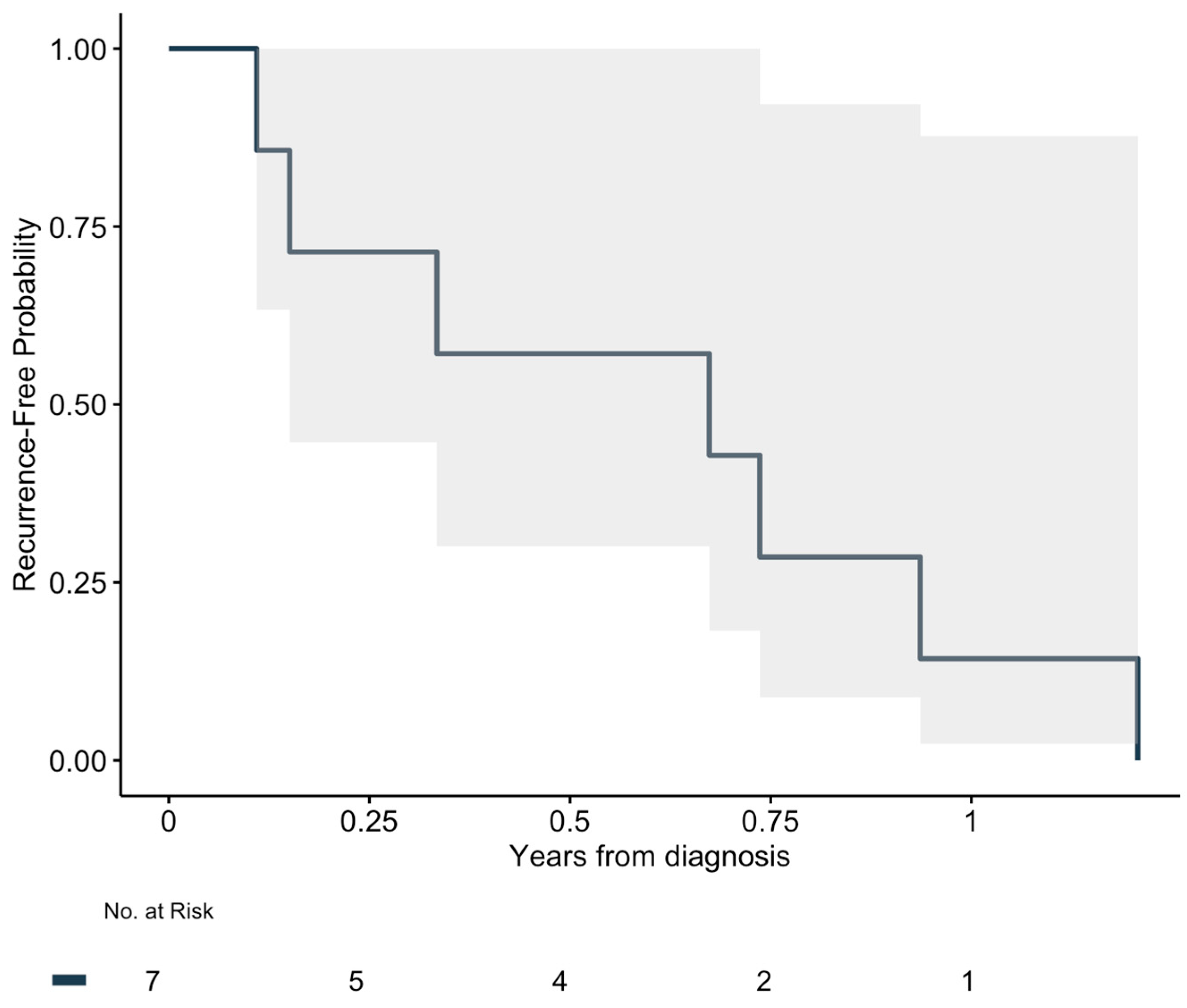

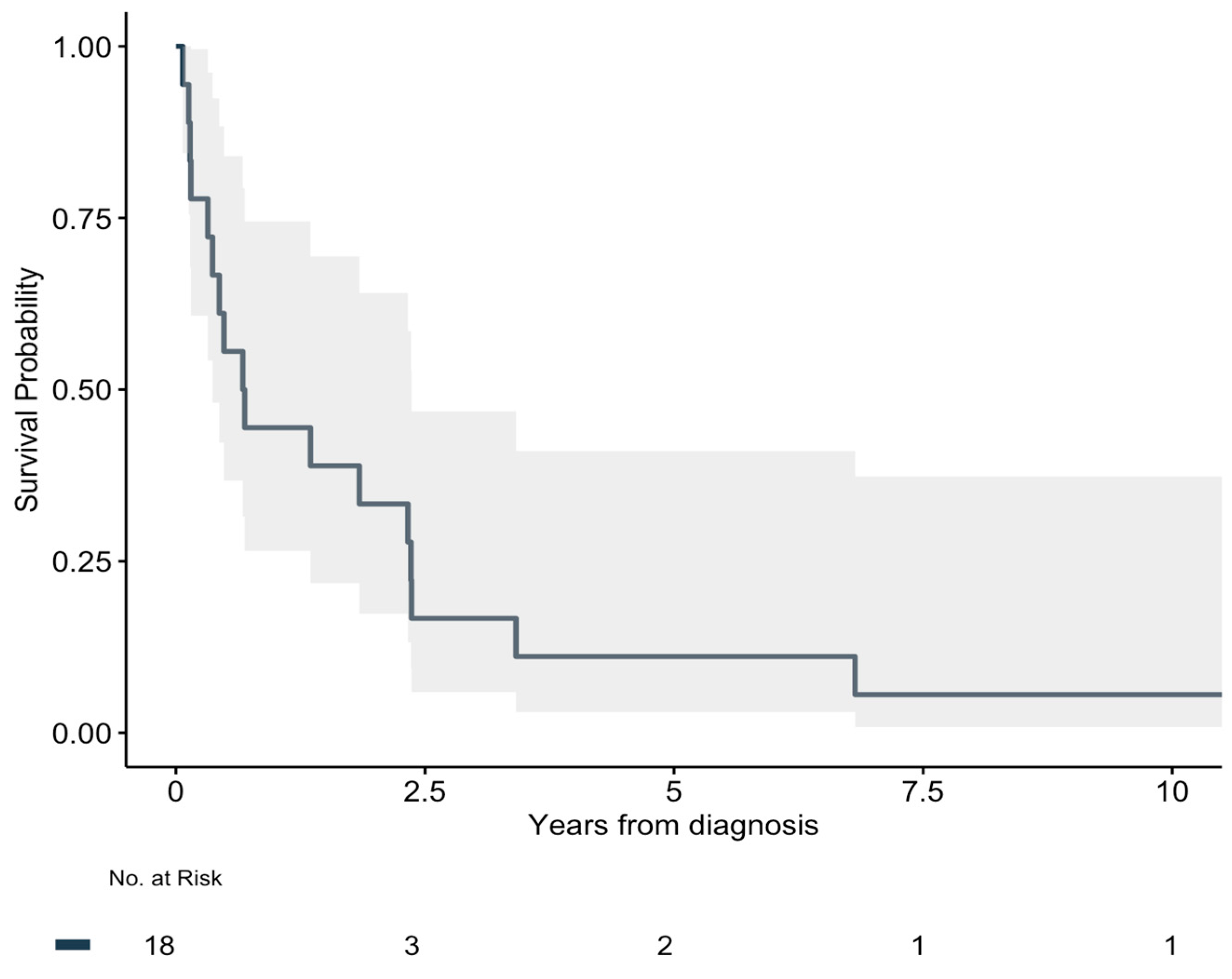

3.3. Recurrence and Overall Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| DSR | Danish Sarcoma Registry |

| DNPR | Danish National Pathology Registry |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| RFS | Recurrence-Free Survival |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SNOMED | Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine |

| IBM | International Business Machines |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

References

- Young, R.J.; Brown, N.J.; Reed, M.W.; Hughes, D.; Woll, P.J. Angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, M.J.; Ravi, V.; Schaub, S.K.; Kim, E.Y.; Sharib, J.; Mogal, H.; Park, M.; Tsai, M.; Duarte-Bateman, D.; Tufaro, A.; et al. Incidence and Presenting Characteristics of Angiosarcoma in the US, 2001–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e246235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florou, V.; Wilky, B.A. Current and Future Directions for Angiosarcoma Therapy. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrick, L.E.; Zambetti, B.R.; Wong, D.L.; Dickson, P.V.; Glazer, E.S.; Shibata, D.; Fleming, M.D.; Tsao, M.; Portnoy, D.C.; Deneve, J.L. Visceral Angiosarcoma: A Nationwide Analysis of Treatment Factors and Outcomes. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 125, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyrup, A.T.; Weiss, S.W. Grading of Soft Tissue Sarcomas: The Challenge of Providing Precise Information in an Imprecise World. Histopathology 2006, 48, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, K.; Wulff, I.; Thorsen, K.V.; Wagenblast, A.L.; Schmidt, G.; Jensen, D.H.; Holm, C.E.; Petersen, M.M.; Loya, A.C.; Mentzel, T.; et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics, Long-Term Prognosis and Follow-up Recommendations of Primary and Secondary Cutaneous Angiosarcoma: A Danish Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 109680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, C.E.; Ørholt, M.; Talman, M.-L.; Abebe, K.; Thorn, A.; Baad-Hansen, T.; Petersen, M.M. A Population-Based Long-Term Follow-Up of Soft Tissue Angiosarcomas: Characteristics, Treatment Outcomes, and Prognostic Factors. Cancers 2024, 16, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penel, N.; Marréaud, S.; Robin, Y.-M.; Hohenberger, P. Angiosarcoma: State of the Art and Perspectives. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2011, 80, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, J.; He, C.; Fang, M. Angiosarcoma: A Review of Diagnosis and Current Treatment. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 2303–2313. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, J.A.; Hornicek, F.J.; Kaufman, A.M.; Harmon, D.C.; Springfield, D.S.; Raskin, K.A.; Mankin, H.J.; Kirsch, D.G.; Rosenberg, A.E.; Nielsen, G.P.; et al. Treatment and Outcome of 82 Patients with Angiosarcoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 14, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merfeld, E.; Gabani, P.; Spraker, M.B.; Zoberi, I.; Kim, H.; Van Tine, B.; Chrisinger, J.; Michalski, J.M. Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Features of Angiosarcoma: Significance of Prior Radiation Therapy. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnolo, B.A.; Zagars, G.K.; Araujo, D.; Ravi, V.; Shellenberger, T.D.; Sturgis, E.M. Outcomes after Definitive Treatment for Cutaneous Angiosarcoma of the Face and Scalp. Head Neck 2011, 33, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.C.; Lluis, N.; Nalesnik, M.A.; Nassar, A.; Serrano, T.; Ramos, E.; Torbenson, M.; Asbun, H.J.; Geller, D.A. Hepatic Angiosarcoma: A Multi-Institutional, International Experience with 44 Cases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, P.; Lausten, G.; Becic Pedersen, A. The Danish Sarcoma Database. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 8, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, B.; Larsen, O.B. The Danish Pathology Register. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Pedersen, L.; Sørensen, H.T. The Danish Civil Registration System as a Tool in Epidemiology. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 29, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shustef, E.; Kazlouskaya, V.; Prieto, V.G.; Ivan, D.; Aung, P.P. Cutaneous Angiosarcoma: A Current Update. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 70, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Cheng, J.; Gong, Z.; Chen, J.; Long, H.; Zhu, B. A Pooled Analysis of Primary Hepatic Angiosarcoma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 50, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shao, J.; Ye, Z. Survival Predictors of Metastatic Angiosarcomas: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Population-Based Retrospective Study. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, D.; Rice, S.R.; Moody, J.S.; Rush, P.; Hafez, G.-R.; Attia, S.; Longley, B.J.; Kozak, K.R. Angiosarcoma Outcomes and Prognostic Factors: A 25-Year Single Institution Experience. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 37, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fury, M.G.; Antonescu, C.R.; Van Zee, K.J.; Brennan, M.F.; Maki, R.G. A 14-Year Retrospective Review of Angiosarcoma: Clinical Characteristics, Prognostic Factors, and Treatment Outcomes with Surgery and Chemotherapy. Cancer J. 2005, 11, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penel, N.; Bui, B.N.; Bay, J.-O.; Cupissol, D.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Kerbrat, P.; Fournier, C.; Taieb, S.; Jimenez, M.; et al. Phase II Trial of Weekly Paclitaxel for Unresectable Angiosarcoma: The ANGIOTAX Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5269–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonescu, C. Malignant Vascular Tumors—An Update. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27 (Suppl. 1), S30–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonito, F.J.P.; de Almeida Cerejeira, D.; Dahlstedt-Ferreira, C.; Oliveira Coelho, H.; Rosas, R. Radiation-Induced Angiosarcoma of the Breast: A Review. Breast J. 2020, 26, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Bhadana, U.; Singh, R.A.K.; Ahuja, A. Primary Hepatic Angiosarcoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Domínguez, D.; Peña Gonzalez, K.B. Radiotherapy-Associated Intra-Abdominal Angiosarcoma after Prostatic Adenocarcinoma: Case Reports. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 9, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Hamacher, K.L. Angiosarcoma in a Chronically Immunosuppressed Renal Transplant Recipient: Report of a Case and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2002, 24, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piamonti, D.; Giannone, S.; D’Antoni, L.; Sanna, A.; Landini, N.; Pernazza, A.; Bassi, M.; Carillo, C.; Diso, D.; Venuta, F.; et al. Bilateral Spontaneous Hemothorax: A Rare Case of Primary Pleural Angiosarcoma and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, N.; Imai, Y.; Cho, T.; Ogawara, Y.; Mizushima, T.; Takase, H.; Fujii, S.; Miyagi, E. Ovarian Angiosarcoma with Intractable Intraperitoneal Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus 2025, 17, e76849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.M.; Madden, B.; Frost, J.; Crane-Okada, R.; Hulsman, R.L.; Elliott, K.; Saria, M.G. Terminal Bleeding in Angiosarcoma. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeyashiki, C.; Nagata, N.; Uemura, N. Angiosarcoma Involving Solid Organs and the Gastrointestinal Tract with Life-Threatening Bleeding. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2012, 6, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, T.M.; Paulino, A.F.; McGinn, C.J.; Baker, L.H.; Cohen, D.S.; Morris, J.S.; Rees, R.; Sondak, V.K. Cutaneous Angiosarcoma of the Scalp: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Cancer 2003, 98, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayette, J.; Martin, E.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Le Cesne, A.; Robert, C.; Bonvalot, S.; Ranchère, D.; Pouillart, P.; Coindre, J.M.; Blay, J.Y. Angiosarcomas, a Heterogeneous Group of Sarcomas with Specific Behavior Depending on Primary Site: A Retrospective Study of 161 Cases. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 2030–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.J.; Woll, P.J. Anti-Angiogenic Therapies for the Treatment of Angiosarcoma: A Clinical Update. MEMO 2017, 10, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.P.; Correa, A.M.; Blackmon, S.; Quiroga-Garza, G.; Weilbaecher, D.; Bruckner, B.; Ramlawi, B.; Rice, D.C.; Vaporciyan, A.A.; Reardon, M.J. Outcomes after Right-Side Heart Sarcoma Resection. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 91, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinidou, A.; Sauve, N.; Stacchiotti, S.; Blay, J.-Y.; Vincenzi, B.; Grignani, G.; Rutkowski, P.; Guida, M.; Hindi, N.; Klein, A.; et al. Evaluation of the Use and Efficacy of (Neo)Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Angiosarcoma: A Multicentre Study. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florou, V.; Rosenberg, A.E.; Wieder, E.; Komanduri, K.V.; Kolonias, D.; Uduman, M.; Castle, J.C.; Buell, J.S.; Trent, J.C.; Wilky, B.A. Angiosarcoma Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Case Series of Seven Patients from a Single Institution. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.J.; Othus, M.; Patel, S.P.; Ryan, C.; Sangal, A.; Powers, B.; Budd, G.T.; Victor, A.I.; Hsueh, C.-T.; Chugh, R.; et al. Multicenter Phase II Trial (SWOG S1609, Cohort 51) of Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Metastatic or Unresectable Angiosarcoma: A Substudy of Dual Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 Blockade in Rare Tumors (DART). J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, J.; Eliott, J.; Neuhaus, S.; Reid, J.; Butow, P. Health-Related Quality of Life, Psychosocial Functioning, and Unmet Health Needs in Patients with Sarcoma: A Systematic Review. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subject | Sex Female (%) | Age, Years Median (IQR) | Location of Primary Tumor | Tumor Size, cm Median (IQR) | Metastases at Diagnosis Yes (%) | Metastases, Later Yes (%) | Metastases, Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 56% | 56.5 years (50–70) | 5 cm (3.2–8) | 17% | 50% | ||

| 1. | Male | 75 | Internal thoracic wall | 10 | No | No | |

| 2. | Female | 22 | Internal thoracic wall or pleura | 1.7 | No | No | - |

| 3. | Male | 73 | Thoracic soft tissue | N/A | No | No | - |

| 4. | Male | 36 | Lung | 6 | No | Yes | Adrenal gland |

| 5. | Female | 70 | Lung | 5 | No | No | - |

| 6. | Male | 44 | Deceased donor kidney | 2.1 | No | Yes | Retroperitoneum |

| 7. | Male | 40 | Deceased donor kidney | 22 | Yes | Yes | Lung |

| 8. | Male | 50 | Kidney | 5 | No | No | - |

| 9. | Female | 51 | Liver | 10 | Yes | Yes | Gallbladder |

| 10. | Female | 68 | Liver | 3.5 | No | No | - |

| 11. | Female | 81 | Liver | 5.2 | No | No | - |

| 12. | Female | 69 | Spleen | N/A | No | Yes | Liver |

| 13. | Female | 76 | Jejenum | 6.7 | No | Yes | Liver |

| 14. | Male | 57 | Caecum | 0.8 | No | Yes | Pleura |

| 15. | Female | 59 | Rectum | 3.1 | No | Yes | Thyroid |

| 16. | Female | 53 | Retroperitoneum/abdomen | 9.3 | No | No | - |

| 17. | Female | 56 | Aorta | 3.2 | No | Yes | - |

| 18. | Male | 55 | Atrium | N/A | Yes | Yes | Lung |

| Subject | Location of Primary Tumor | Surgery Yes (%) | R0 Yes (%) | RT Adjuv. Yes (%) | RT Pall. Yes (%) | Chemo Adjuv Yes (%) | Chemo Pall. Yes (%) | Recurrence or Mets. for R0 Yes (%) | Recurrence Free Survival, Days Median (IQR) | Surgery for Mets. Yes (%) | Death Yes (%) | Overall Survival, Days Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 61% | 64% | 6% | 28% | 0% | 50% | 100% of R0 | 246 days (89–306) | 50% of mets. | 94% | 249 days (121–858) | |

| 1. Male, 75 years | Internal thoracic wall | No | - | No | No | No | No | - | - | - | Yes | 47 |

| 2. Female, 22 years | Internal thoracic wall or pleura | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | - | - | - | Yes | 252 |

| 3. Male, 73 years | Thoracic soft tissue | No | - | No | Yes | No | No | - | - | - | Yes | 117 |

| 4. Male, 36 years | Lung | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 269 | Yes, two | Yes | 1246 |

| 5. Female, 70 years | Lung | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 40 | - | Yes | 55 |

| 6. Male, 44 years | Deceased donor kidney | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | - | - | Yes, three | No | 4027 |

| 7. Male, 40 years | Deceased donor kidney | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | - | - | No | Yes | 52 |

| 8. Male, 50 years | Kidney | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | - | - | - | Yes | 176 |

| 9. Female 51 years | Liver | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | 441 | Yes, one | Yes | 2488 |

| 10. Female 68 years | Liver | No | - | No | No | No | Yes | - | - | - | Yes | 245 |

| 11. Female, 81 years | Liver | No | - | No | No | No | No | - | - | - | Yes | 493 |

| 12. Female, 69 years | Spleen | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 246 | No | Yes | 863 |

| 13. Female, 76 years | Jejenum | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 342 | - | Yes | 672 |

| 14. Male, 57 years | Caecum | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 122 | No | Yes | 134 |

| 15. Female, 59 years | Rectum | No | - | No | Yes | No | Yes | - | - | Yes, one | Yes | 861 |

| 16. Female, 53 years | Retroperitoneum/abdomen | No | - | No | No | No | No | - | - | - | Yes | 25 |

| 17. Female, 56 years | Aorta | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 55 | - | Yes | 850 |

| 18. Male, 55 years | Atrium | No | - | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | - | - | No | Yes | 159 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehné Jensen, L.; Holm, C.E.; Tolstrup, J.; Ørholt, M.; Petersen, M.M.; Penninga, L. Visceral Angiosarcoma: A Nationwide Population-Based Study from 2000–2017. Cancers 2025, 17, 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132101

Rehné Jensen L, Holm CE, Tolstrup J, Ørholt M, Petersen MM, Penninga L. Visceral Angiosarcoma: A Nationwide Population-Based Study from 2000–2017. Cancers. 2025; 17(13):2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132101

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehné Jensen, Lasse, Christina Enciso Holm, Johan Tolstrup, Mathias Ørholt, Michael Mørk Petersen, and Luit Penninga. 2025. "Visceral Angiosarcoma: A Nationwide Population-Based Study from 2000–2017" Cancers 17, no. 13: 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132101

APA StyleRehné Jensen, L., Holm, C. E., Tolstrup, J., Ørholt, M., Petersen, M. M., & Penninga, L. (2025). Visceral Angiosarcoma: A Nationwide Population-Based Study from 2000–2017. Cancers, 17(13), 2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132101