Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Nab-Paclitaxel Treatment in Elderly Patients with HER-2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: NEREIDE Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

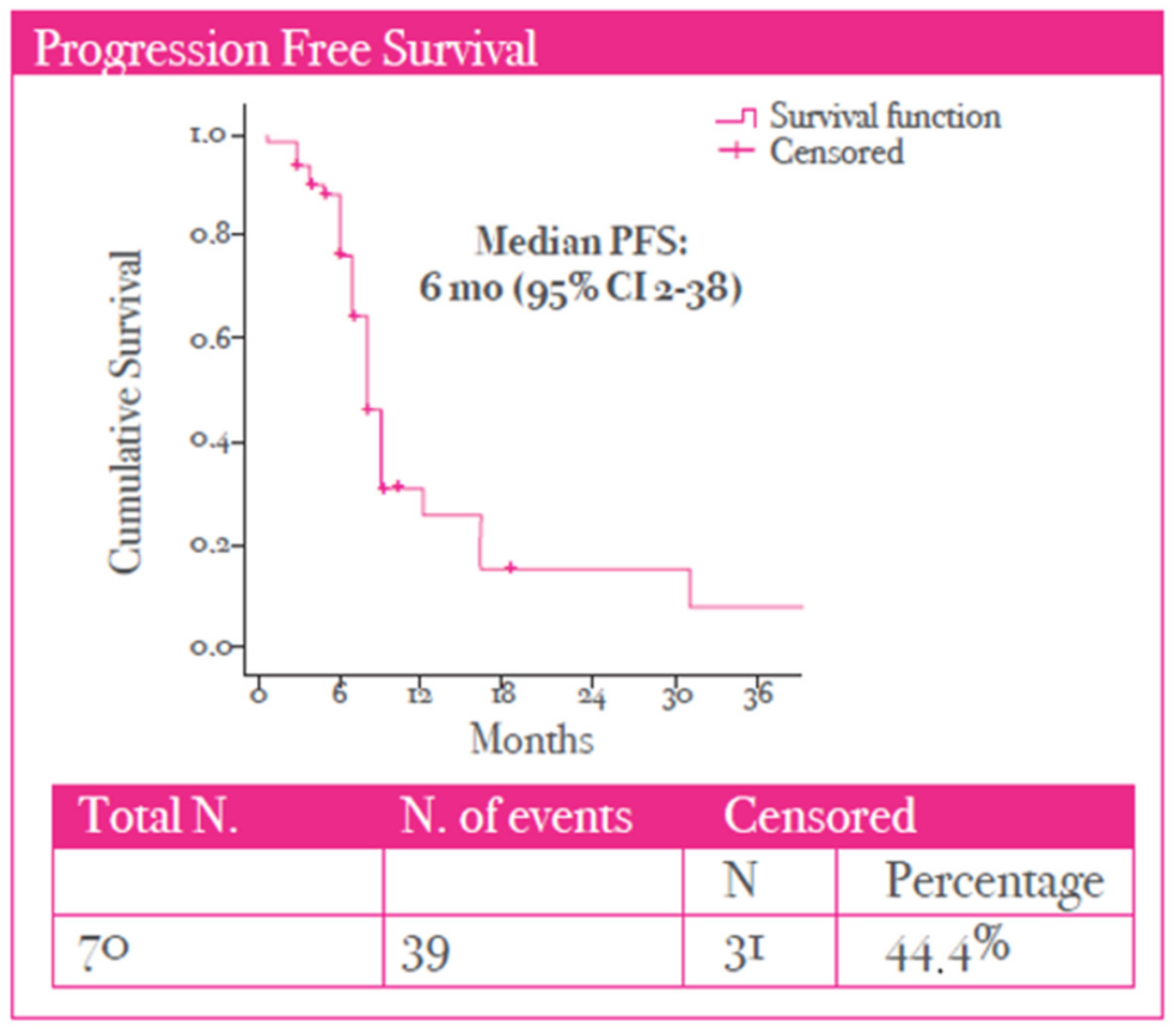

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mBC | Metastatic breast cancer |

| Nab-P | Nab-paclitaxel |

| Three letter acronym | |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| OS | Overall survival |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

References

- Łukasiewicz, S.; Czeczelewski, M.; Forma, A.; Baj, J.; Sitarz, R.; Stanisławek, A. Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- de Kruijf, E.M.; Bastiaannet, E.; Rubertá, F.; de Craen, A.J.; Kuppen, P.J.; Smit, V.T.; van de Velde, C.J.; Liefers, G.J. Comparison of frequencies and prognostic effect of molecular subtypes between young and elderly breast cancer patients. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.O.; Deal, A.M.; Anders, C.K.; Prat, A.; Perou, C.M.; Carey, L.A.; Muss, H.B. Age-specific changes in intrinsic breast cancer subtypes: A focus on older women. Oncologist 2014, 19, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheampong, T.; Kehm, R.D.; Terry, M.B.; Argov, E.L.; Tehranifar, P. Incidence Trends of Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes by Age and Race/Ethnicity in the US from 2010 to 2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2013226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchardy, C.; Rapiti, E.; Fioretta, G.; Laissue, P.; Neyroud-Caspar, I.; Schäfer, P.; Kurtz, J.; Sappino, A.P.; Vlastos, G. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3580–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puts, M.T.E.; Tu, H.A.; Tourangeau, A.; Howell, D.; Fitch, M.; Springall, E.; Alibhai, S.M.H. Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, L.; Extermann, M. Management of cancer in the older person: A practical approach. Oncologist 2000, 5, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, K.P.; Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Hsu, T.; de Glas, N.A.; Battisti, N.M.L.; Baldini, C.; Rodrigues, M.; Lichtman, S.M.; Wildiers, H. What Every Oncologist Should Know About Geriatric Assessment for Older Patients with Cancer: Young International Society of Geriatric Oncology Position Paper. J. Oncol. Pract. 2018, 14, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Chemotherapy: ASCO Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Li, D.; Yuan, Y.; Lau, Y.M.; Hurria, A. Functional versus chronological age: Geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e305–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, W.; Klepin, H.D.; Williams, G.R.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Bergerot, C.; Brintzenhofeszoc, K.; Hopkins, J.O.; Jhawer, M.P.; Katheria, V.; Loh, K.P.; et al. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic Cancer Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4293–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Senkus, E.; Curigliano, G.; Aapro, M.S.; André, F.; Barrios, C.H.; Bergh, J.; Bhattacharyya, G.S.; Biganzoli, L.; et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1623–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brain, E.; Caillet, P.; de Glas, N.; Biganzoli, L.; Cheng, K.; Lago, L.D.; Wildiers, H. HER2-targeted treatment for older patients with breast cancer: An expert position paper from the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradishar, W.J. Taxanes for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2012, 6, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghersi, D.; Willson, M.L.; Chan, M.M.K.; Simes, J.; Donoghue, E.; Wilcken, N. Taxane-containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD003366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.B.; Donehower, R.C.; Wiernik, P.H.; Ohnuma, T.; Gralla, R.J.; Trump, D.L.; Baker, J.R., Jr.; Van Echo, D.A.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Leyland-Jones, B. Hypersensitivity reactions from taxol. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 8, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparreboom, A.; van Zuylen, L.; Brouwer, E.; Loos, W.J.; de Bruijn, P.; Gelderblom, H.; Pillay, M.; Nooter, K.; Stoter, G.; Verweij, J. Cremophor EL-mediated alteration of paclitaxel distribution in human blood: Clinical pharmacokinetic implications. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 1454–1457. [Google Scholar]

- ten Tije, A.J.; Verweij, J.; Loos, W.J.; Sparreboom, A. Pharmacological effects of formulation vehicles: Implications for cancer chemotherapy. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Paridaens, R. Taxanes in elderly breast cancer patients. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2004, 30, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Tjulandin, S.; Davidson, N.; Shaw, H.; Desai, N.; Bhar, P.; Hawkins, M.; O’Shaughnessy, J. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7794–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradishar, W.J.; Krasnojon, D.; Cheporov, S.; Makhson, A.N.; Manikhas, G.M.; Clawson, A.; Bhar, P. Significantly longer progression-free survival with nab-paclitaxel compared with docetaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3611–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aapro, M.; Tjulandin, S.; Bhar, P.; Gradishar, W. Weekly nab-paclitaxel is safe and effective in ≥65 years old patients with metastatic breast cancer: A post-hoc analysis. Breast 2011, 20, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganzoli, L.; Cinieri, S.; Berardi, R.; Pedersini, R.; McCartney, A.; Minisini, A.M.; Caremoli, E.R.; Spazzapan, S.; Magnolfi, E.; Brunello, A.; et al. EFFECT: A randomized phase II study of efficacy and impact on function of two doses of nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment in older women with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumarianou, A.; Makrantonakis, P.; Zagouri, F.; Papadimitriou, C.; Christopoulou, A.; Samantas, E.; Christodoulou, C.; Psyrri, A.; Bafaloukos, D.; Aravantinos, G.; et al. ABREAST: A prospective, real-world study on the effect of nab-paclitaxel treatment on clinical outcomes and quality of life of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 182, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer. 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, D.A. Taxanes in the elderly patient with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2015, 7, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.D.; Jiang, J.; McLaughlin, S.S.; Hurria, A.; Smith, G.L.; Giordano, S.H.; Buchholz, T.A. Improvement in breast cancer outcomes over time: Are older women missing out? J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4647–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganzoli, L.; Wildiers, H.; Oakman, C.; Marotti, L.; Loibl, S.; Kunkler, I.; Reed, M.; Ciatto, S.; Voogd, A.C.; Brain, E.; et al. Management of elderly patients with breast cancer: Updated recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA). Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, e148–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, I.; Lafont, C.; Liposits, G.; Vidra, R.; Cunquero-Tomás, A.J.; Korobeinikova, E.; Neuendorff, N.R.; Slavova-Boneva, V.; Baltussen, J.; Chovanec, M.; et al. Representation of geriatric oncology in cancer care guidelines in Europe: A scoping review by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). ESMO Open 2025, 10, 105052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganzoli, L.; Aapro, M.; Loibl, S.; Wildiers, H.; Brain, E. Taxanes in the treatment of breast cancer: Have we better defined their role in older patients? A position paper from a SIOG Task Force. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 43, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Tije, A.J.; Smorenburg, C.H.; Seynaeve, C.; Sparreboom, A.; Schothorst, K.L.; Kerkhofs, L.G.; van Reisen, L.G.; Stoter, G.; Bontenbal, M.; Verweij, J. Weekly paclitaxel as first-line chemotherapy for elderly patients with metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

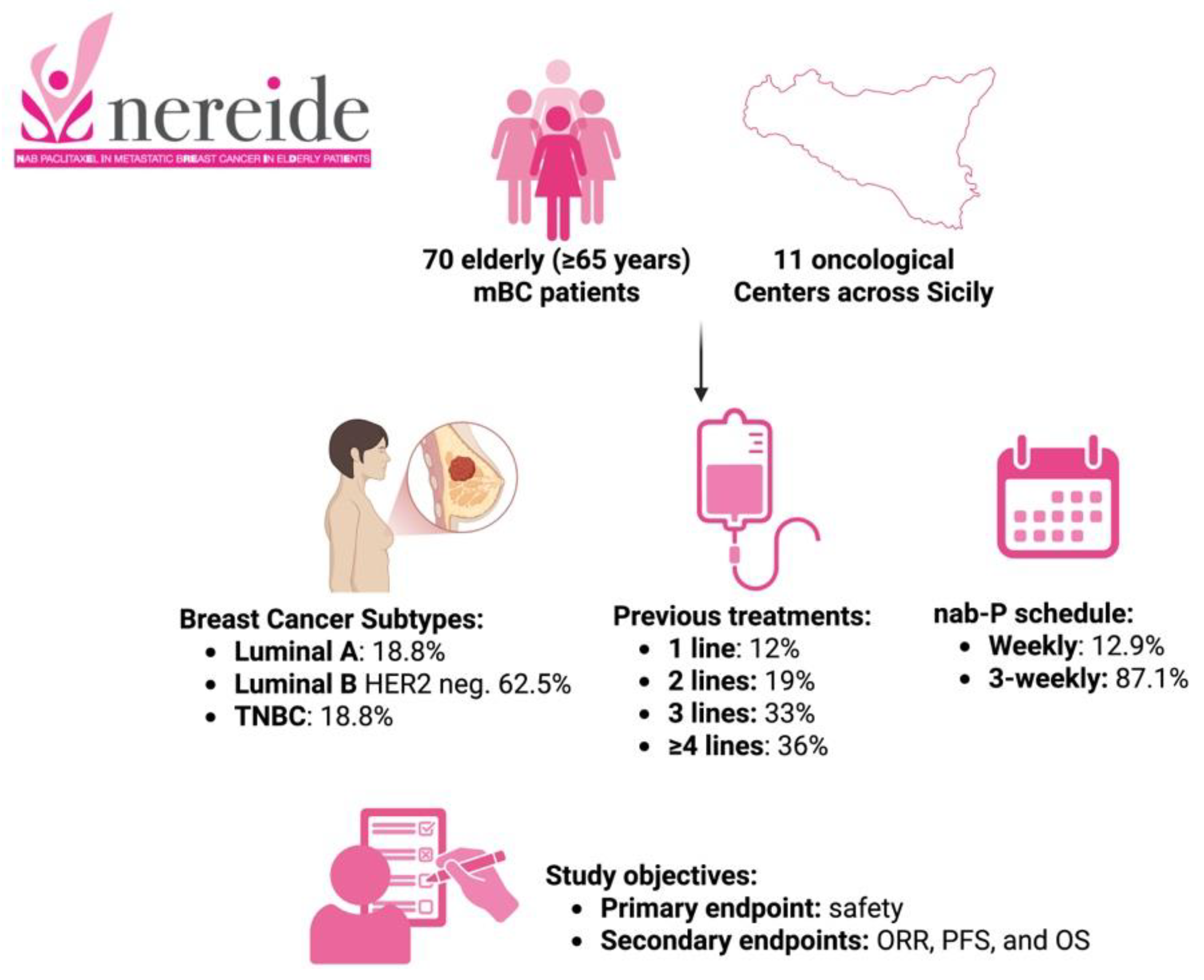

| Patients, n | 70 |

| Median age (years), range | 67 (65–83) |

| Breast cancer subtypes | Luminal A, 18.75% |

| Luminal B HER2-negative, 62.5% | |

| Triple-negative, 18.75% | |

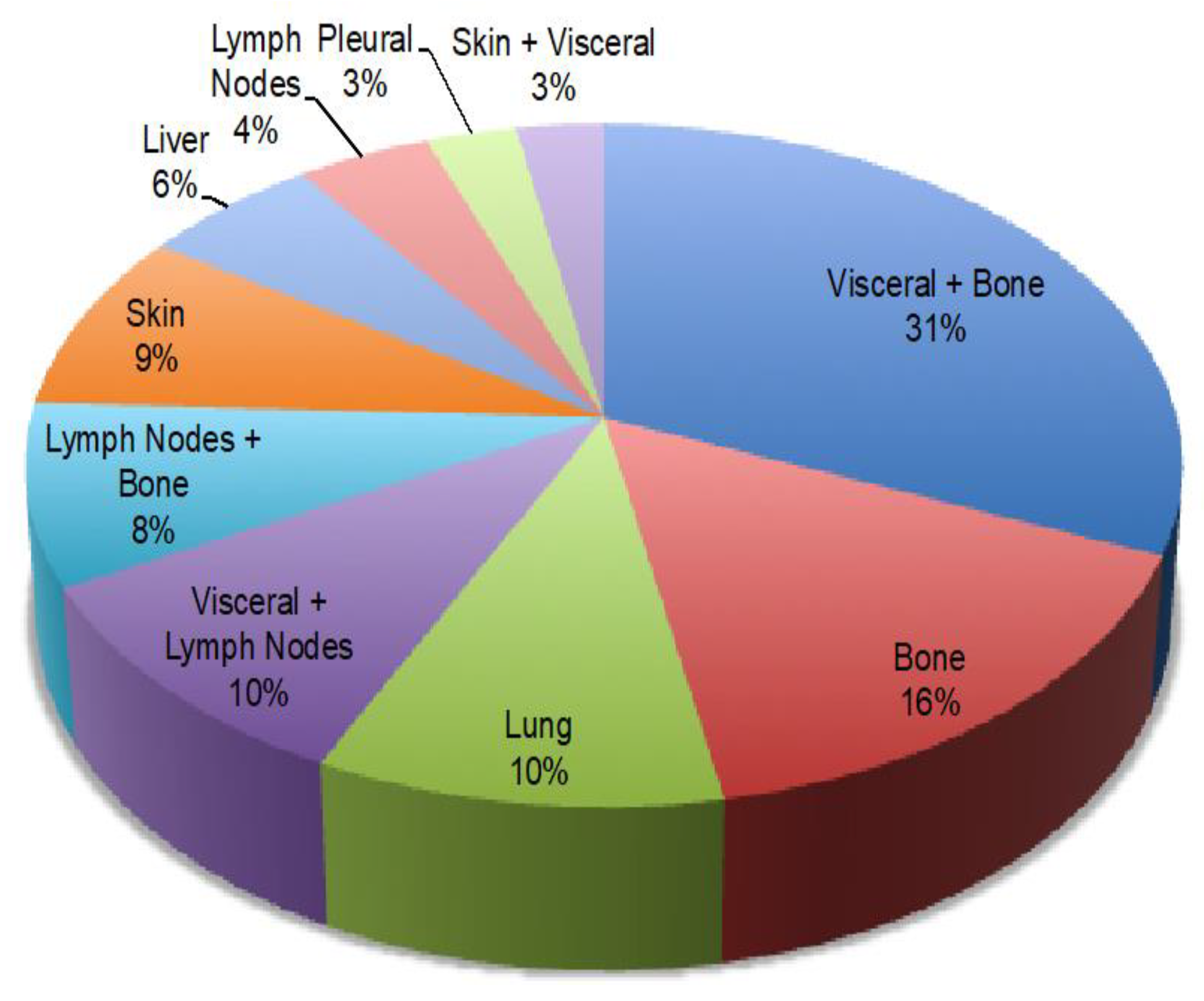

| Metastatic site distribution | Visceral + bone, 31.4% |

| Bone, 15.7% | |

| Lung, 10% | |

| Visceral and lymph nodes, 10% | |

| Lymph nodes and bones, 8.6% | |

| Liver, 5.7% | |

| Others, 10% | |

| Number of lines | 1 line, 12% |

| 2 lines, 19% | |

| 3 lines, 33% | |

| ≥4 lines, 36% | |

| Nab-paclitaxel schedule | Weekly, 12.9% |

| 3-weekly, 87.1% |

| Overview of Adverse Events | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Dose reduction | 35.5 |

| Treatment discontinuation (%) | 11.5 |

| Major adverse events (%) | |

| Fatigue | 61.5 |

| Neuropathy | 53.8 |

| Leukopenia | 39.1 |

| Nausea | 21.9 |

| Diarrhea | 17.2 |

| Anemia | 14.1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 12.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ricciardi, G.R.R.; Russo, A.; Sanò, M.V.; Prestifilippo, A.; Russo, A.; Gebbia, V.; Blasi, L.; Giuffrida, D.; Scandurra, G.; Savarino, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Nab-Paclitaxel Treatment in Elderly Patients with HER-2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: NEREIDE Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132069

Ricciardi GRR, Russo A, Sanò MV, Prestifilippo A, Russo A, Gebbia V, Blasi L, Giuffrida D, Scandurra G, Savarino A, et al. Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Nab-Paclitaxel Treatment in Elderly Patients with HER-2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: NEREIDE Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(13):2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132069

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicciardi, Giuseppina Rosaria Rita, Alessandro Russo, Maria Vita Sanò, Angela Prestifilippo, Antonio Russo, Vittorio Gebbia, Livio Blasi, Dario Giuffrida, Giuseppa Scandurra, Antonio Savarino, and et al. 2025. "Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Nab-Paclitaxel Treatment in Elderly Patients with HER-2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: NEREIDE Study" Cancers 17, no. 13: 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132069

APA StyleRicciardi, G. R. R., Russo, A., Sanò, M. V., Prestifilippo, A., Russo, A., Gebbia, V., Blasi, L., Giuffrida, D., Scandurra, G., Savarino, A., Butera, A., Borsellino, N., Verderame, F., Caruso, M., & Adamo, V. (2025). Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Nab-Paclitaxel Treatment in Elderly Patients with HER-2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: NEREIDE Study. Cancers, 17(13), 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17132069