Evaluation of the Implementation of the Dutch Breast Cancer Surveillance Decision Aid including Personalized Risk Estimates in the SHOUT-BC Study: A Mixed Methods Approach

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

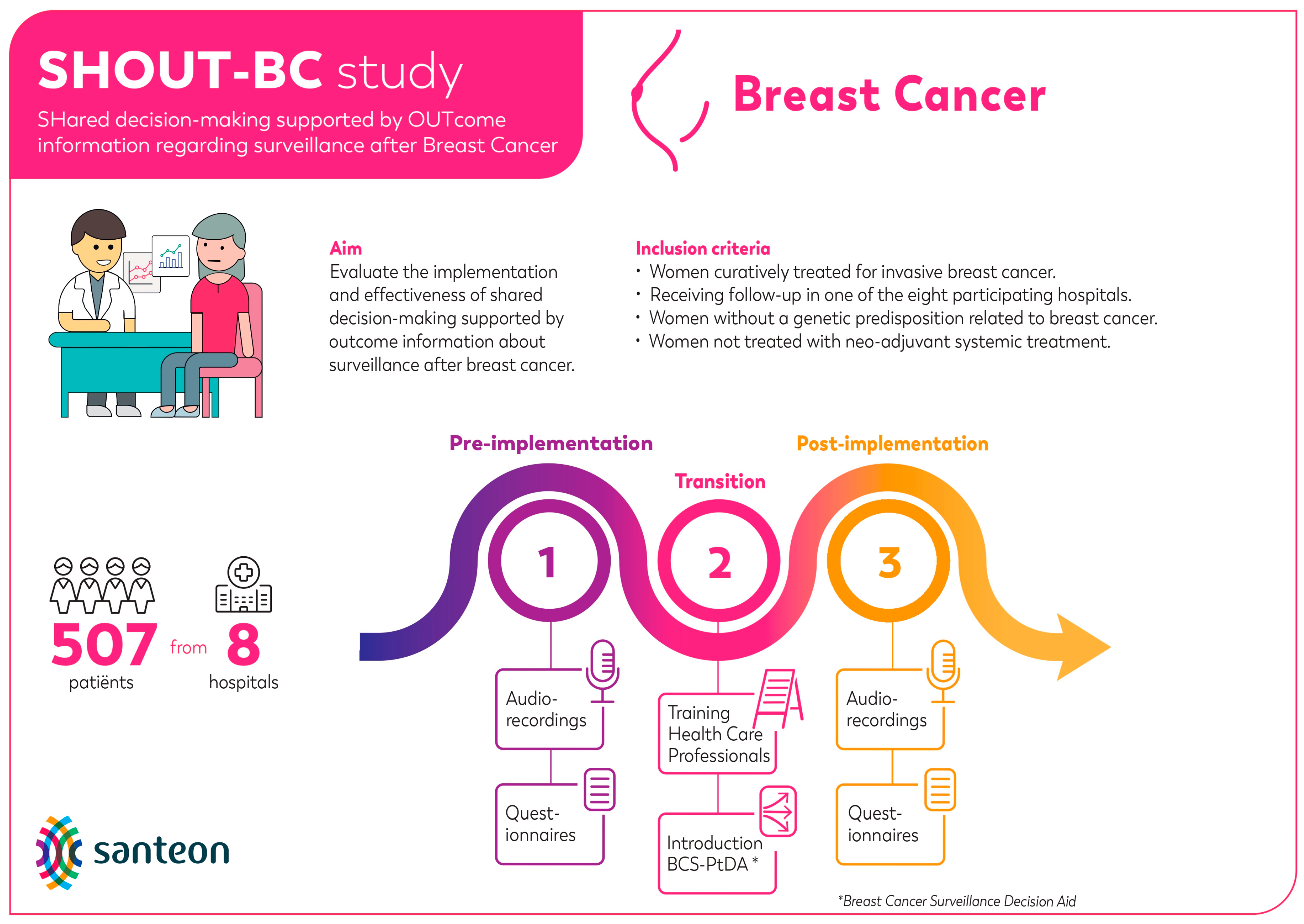

2.1. Study Design

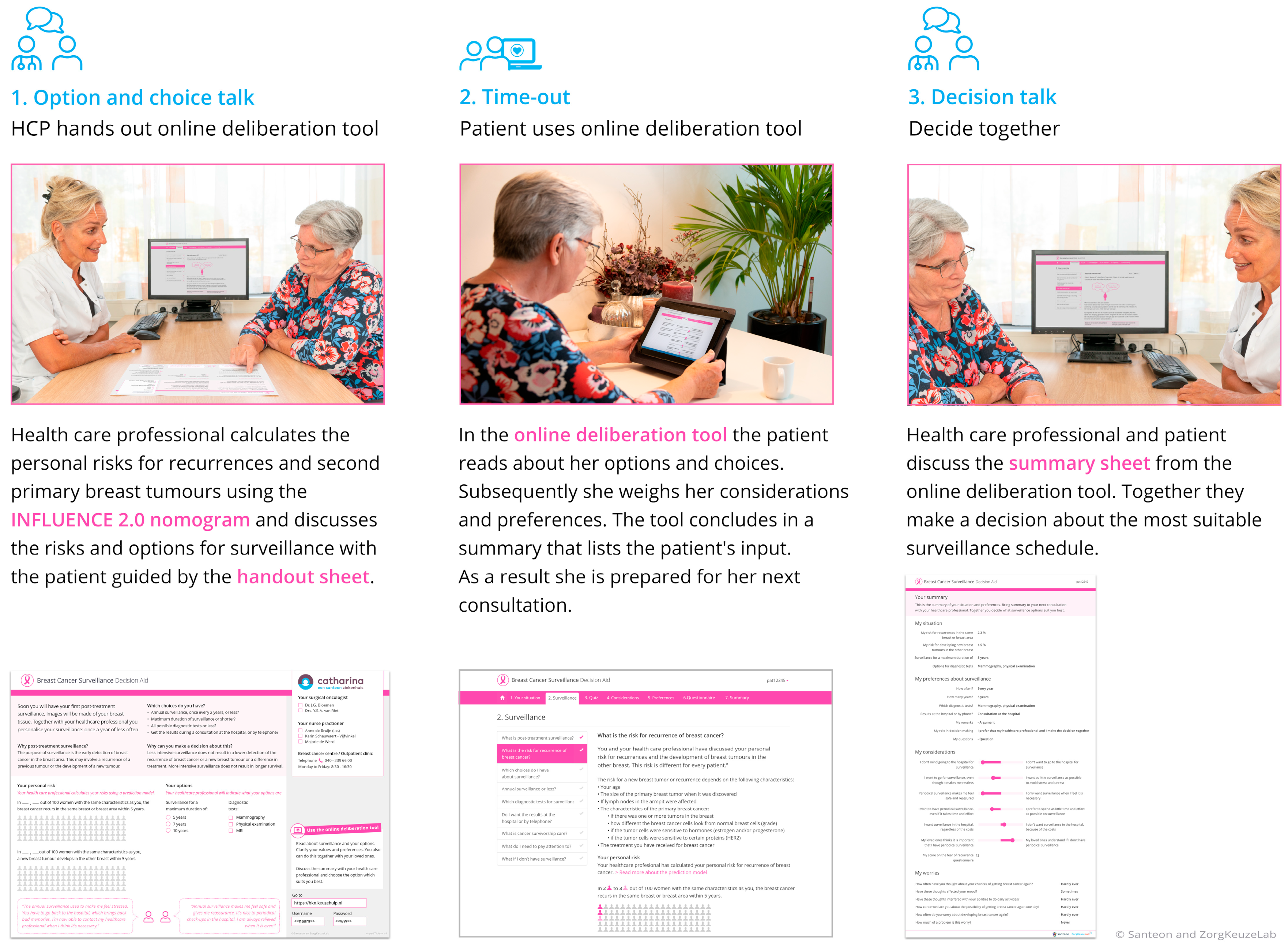

2.2. Breast Cancer Surveillance Decision Aid

2.3. Measures and Procedures

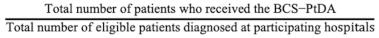

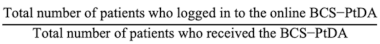

2.3.1. Aim 1: Assessing the BCS-PtDA Implementation and Participation Rate

2.3.2. Aim 2: Identifying Facilitators and Barriers of PtDA Use by HCPs

2.3.3. Aim 3: Quantifying the Observed Level of SDM

2.3.4. Aim 4: Qualitatively Assessing Risk Communication and SDM Application in Doctor–Patient Consultations after Implementation of the BCS-PtDA

3. Results

3.1. Aim 1: Assessing the BCS-PtDA Implementation and Participation Rate

3.2. Aim 2: Identifying Facilitators and Barriers of BCS-PtDA Use by HCPs

3.3. Aim 3: Quantifying the Observed Level of SDM

3.4. Aim 4: Qualitatively Assessing Risk Communication and SDM Application in Doctor–Patient Consultations after Implementation of the BCS-PtDA

3.4.1. Creating Choice Awareness

3.4.2. Information Provision

Presentation of Options

3.4.3. Risk Communication

3.4.4. Deliberation and Decision-Making

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practice Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Völkel, V.; Hueting, T.A.; Draeger, T.; van Maaren, M.C.; de Munck, L.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; Sonke, G.S.; Schmidt, M.K.; van Hezewijk, M.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.M.; et al. Improved risk estimation of locoregional recurrence, secondary contralateral tumors and distant metastases in early breast cancer: The INFLUENCE 2.0 model. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 189, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteveen, A.; Vliegen, I.M.H.; Sonke, G.S.; Klaase, J.M.; IJzerman, M.J.; Siesling, S. Personalisation of breast cancer follow-up: A time-dependent prognostic nomogram for the estimation of annual risk of locoregional recurrence in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 152, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NABON. Breast Cancer—Dutch Guideline, Version 2.0. Oncoline. 2012. Available online: https://www.nabon.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Dutch-Breast-Cancer-Guideline-2012.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Witteveen, A.; Otten, J.W.M.; Vliegen, I.M.H.; Siesling, S.; Timmer, J.B.; IJzerman, M.J. Risk-based breast cancer follow-up stratified by age. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5291–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschetti, I.; Cinquini, M.; Lambertini, M.; Levaggi, A.; Liberati, A. Follow-up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD001768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ligt, K.M.; van Egdom, L.S.E.; Koppert, L.B.; Siesling, S.; van Til, J.A. Opportunities for personalised follow-up care among patients with breast cancer: A scoping review to identify preference-sensitive decisions. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiggelbout, A.M.; Pieterse, A.H.; De Haes, J.C.J.M. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couët, N.; Desroches, S.; Robitaille, H.; Vaillancourt, H.; Leblanc, A.; Turcotte, S.; Elwyn, G.; Légaré, F. Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: A systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 542–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Lewis, K.B.; Smith, M.; Carley, M.; Volk, R.; Douglas, E.E.; Pacheco-Brousseau, L.; Finderup, J.; Gunderson, J.; Barry, M.J.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2024, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankersmid, J.W.; Siesling, S.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; Meulepas, J.M.; van Riet, Y.E.A.; Engels, N.; Prick, J.C.M.; The, R.; Takahashi, A.; Velting, M.; et al. Supporting Shared Decision-making About Surveillance After Breast Cancer With Personalized Recurrence Risk Calculations: Development of a Patient Decision Aid Using the International Patient Decision AIDS Standards Development Process in Combination With a Mixed Methods Design. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8, e38088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Abhyankar, P.; Boland, L.; Bravo, P.; Brenner, A.T.; Brodney, S.; Coulter, A.; Giguère, A.; Hoffman, A.; Körner, M.; et al. What Works in Implementing Patient Decision Aids in Routine Clinical Settings? A Rapid Realist Review and Update from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration. Med. Decis. Mak. 2021, 41, 907–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipkus, I.M.; Samsa, G.; Rimer, B.K. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med. Decis. Mak. 2001, 21, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkus, I.M.; Peters, E.; Kimmick, G.; Liotcheva, V.; Marcom, P. Breast cancer patients’ treatment expectations after exposure to the decision aid program adjuvant online: The influence of numeracy. Med. Decis. Mak. 2010, 30, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Galesic, M. Why do single event probabilities confuse patients? BMJ 2012, 344, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Gaissmaier, W.; Kurz-Milcke, E.; Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S. Helping Doctors and Patients Make Sense of Health Statistics. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2007, 8, 53–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischoff, B.; Brewer, N.T.; Downs, J. Communicating Risks and Benfits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.K.; Joekes, K.; Mills, G.; Gutheil, C.; Smith, K.; Cochran, N.E.; Elwyn, G. Development and evaluation of the “BRISK Scale,” a brief observational measure of risk communication competence. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 2091–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackert, M.Q.N.; Ankersmid, J.W.; Engels, N.; Prick, J.C.M.; Teerenstra, S.; Siesling, S.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; van Riet, Y.E.A.; van den Dorpel, R.M.A.; et al. Effectiveness and implementation of SHared decision-making supported by OUTcome information among patients with breast cancer, stroke and advanced kidney disease: SHOUT study protocol of multiple interrupted time series. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankersmid, J.W.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; Hackert, M.Q.N.; Engels, N.; Prick, J.C.M.; Teerenstra, S.; van Riet, Y.E.A.; The, R.; van Uden-Kraan, C.F.; et al. Shared decision-making supported by OUTcome information regarding surveillance after curative treatment for Breast Cancer: Results of the SHOUT-BC study. Submitted.

- Fleuren, M.A.H.; Paulussen, T.G.W.M.; Van Dommelen, P.; Van Buuren, S. Towards a measurement instrument for determinants of innovations. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2014, 26, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, J.A.E.; van den Berg, S.W.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Bleiker, E.M.A.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Prins, J.B. The Cancer Worry Scale: Detecting fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, E44–E50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, S.A.; Sint Nicolaas, S.M.; Haverman, L.; Wensing, M.; Schouten van Meeteren, A.Y.N.; Veening, M.A.; Caron, H.N.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; Verhaak, C.M.; et al. Real-world implementation of electronic patient-reported outcomes in outpatient pediatric cancer care. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 26, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Tsulukidze, M.; Edwards, A.; Légaré, F.; Newcombe, R. Using a “talk” model of shared decision making to propose an observation-based measure: Observer OPTION5 Item. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 93, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, M.; Al-Itejawi, H.H.M.; van Uden-Kraan, C.F.; Stalmeier, P.F.M.; Lamers, R.E.D.; van Oort, I.M.; Somford, D.M.; van Moorselaar, R.J.A.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; et al. Introducing Decision Aids into Routine Prostate Cancer Care in The Netherlands: Implementation and Patient Evaluations from the Multi-regional JIPPA Initiative. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Suwalska, V.; Boland, L.; Lewis, K.B.; Presseau, J.; Thomson, R. Are Patient Decision Aids Used in Clinical Practice after Rigorous Evaluation? A Survey of Trial Authors. Med. Decis. Mak. 2019, 39, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pass, M.; Belkora, J.; Moore, D.; Volz, S.; Sepucha, K. Patient and observer ratings of physician shared decision making behaviors in breast cancer consultations. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 88, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, S.E.R.; Ubbink, D.T.; Stubenrouch, F.E.; Koelemay, M.J.W.; van der Vleuten, C.J.M.; Verhoeven, B.H.; Reekers, J.A.; Schultze Kool, L.J.; van der Horst, C.M.A.M. Shared Decision-Making in the Management of Congenital Vascular Malformations. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 139, 725e–734e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagt, A.C.; Bos, N.; Bakker, M.; de Boer, D.; Friele, R.D.; de Jong, J.D. A scoping review into the explanations for differences in the degrees of shared decision making experienced by patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2024, 118, 108030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.K.; Joekes, K.; Elwyn, G.; Mazor, K.M.; Thomson, R.; Sedgwick, P.; Ibison, J.; Wong, J.B. Development and evaluation of a risk communication curriculum for medical students. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Aims | Measures | Methods | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aim 1 Assessing the BCS-PtDA implementation and participation * rate. | Implementation rate: Participation rate:  The implementation and participation rates were calculated overall and per hospital. | Descriptive analysis of registry and log data:

| Registry data from women meeting the SHOUT-BC inclusion criteria who were treated at a participating hospital and log data from women who were issued the online BCS-PtDA. |

| Aim 2 Identifying facilitators and barriers of BCS-PtDA use by HCPs. | MIDI: The innovation, user, and organization scales of the MIDI questionnaire were used to obtain insights into the determinants affecting the implementation of the BCS-PtDA (original version, in Dutch) [20]. MIDI items that were answered by ≥20% of HCPs with “totally disagree/disagree” were considered barriers, and items answered by ≥80% with “agree/totally agree” were considered facilitators [22]. | Descriptive analysis of survey data: Data collected using an online survey. | Survey data from all HCPs who could hand out the BCS-PtDA in hospitals participating in the SHOUT-BC study. |

| Aim 3 Quantifying the observed level of SDM after implementation of the BCS-PtDA. | Observed level of SDM: The OPTION-5 scale [23] was used. | Quantitative analysis of consultation transcripts: Consultations were double-coded using the OPTION-5 scale. Differences in coding were resolved through consensus. | Transcripts of consultations with women participating in the SHOUT-BC study. |

| Aim 4 Qualitatively assessing risk communication and SDM application in doctor–patient consultations after implementation of the BCS-PtDA. | Qualitative content analysis consultations: a self-developed coding framework based on the 4-step SDM model by Stiggelbout et al. [7] and the BRISK scale components [17] was used. We also coded the duration of the consultation. | Qualitative analysis of consultation transcripts: Consultations were double coded using a combined technique of deductive and inductive thematic analysis. Differences in coding were resolved through consensus. | Transcripts of consultations with women participating in the SHOUT-BC study. |

| Hospital | Number of Patients Eligible to Receive BCS-PtDA (A) | Number of Patients Who Received the BCS-PtDA (B) | Number of Patients Who Logged in to the BCS-PtDA (C) | Implementation Rate (B/A, %) | Participation Rate (C/B, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 245 | 103 | 73 | 42 | 71 |

| 2 | 265 | 51 | 38 | 19 | 75 |

| 3 | 306 | 65 | 54 | 21 | 83 |

| 4 | 318 | 67 | 22 | 21 | 33 |

| 5 | 245 | 95 | 49 | 39 | 52 |

| 6 | 373 | 70 | 48 | 19 | 69 |

| 7 | 82 | 27 | 12 | 33 | 44 |

| 8 | N/A | 14 | 4 | N/A | 29 |

| Total | 1834 | 492 | 300 | 26 | 61 |

| Determinants Associated with the Innovation (BCS-PtDA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Totally Agree/ Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Totally Disagree/ Disagree (%) | |

| Procedural clarity: it is clear which activities I should perform when offering the BCS-PtDA | 79 | 8 | 13 |

| Correctness: the BCS-PtDA is based on factually correct knowledge | 88 | 4 | 8 |

| Completeness: all information and materials to work with the BCS-PtDA properly are provided | 83 | 4 | 13 |

| Complexity: the BCS-PtDA is not too complex for me to use a | 83 | 13 | 4 |

| Compatibility: the BCS-PtDA is a good match for how I am used to working | 58 | 25 | 17 |

| Observability: the outcomes of using the BCS-PtDA are clearly observable | 29 | 33 | 38 |

| Relevance for patient: the BCS-PtDA is relevant for my patients | 58 | 33 | 8 |

| Determinants Associated with the Users (i.e., Patients and HCPs) | |||

| Totally agree/ Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Totally disagree/ Disagree (%) | |

| Personal benefits: the BCS-PtDA saves me time in informing my patients | 0 | 29 | 71 |

| Personal benefits: the BCS-PtDA provides me more time to discuss the considerations and preferences of my patients with them | 25 | 25 | 51 |

| Personal drawback: my workload has not increased by using the BCS-PtDA a | 8 | 25 | 67 |

| Outcome expectations (importance): the BCS-PtDA helps to create awareness that there is a choice regarding the organization of post-treatment surveillance | 92 | 4 | 4 |

| Outcome expectations (importance): the BCS-PtDA helps to inform about and discuss the different options regarding the organization of post-treatment surveillance | 79 | 13 | 8 |

| Outcome expectations (importance): the BCS-PtDA helps to clarify the wishes and preferences of my patients regarding the organization of post-treatment surveillance | 75 | 17 | 8 |

| Outcome expectations (importance): the BCS-PtDA helps to make a shared decision regarding the organization of post-treatment surveillance | 79 | 17 | 4 |

| Professional obligation: I feel that it is my responsibility to use the BCS-PtDA | 63 | 21 | 17 |

| Patient satisfaction: patients are generally satisfied when I use the BCS-PtDA | 54 | 29 | 17 |

| Patient cooperation: patients generally cooperate when I use the BCS-PtDA | 58 | 33 | 8 |

| Social support: I can count on adequate assistance from my colleagues if I need it to use the BCS-PtDA | 83 | 17 | 0 |

| Social support: I can count on adequate assistance from my superior if I need it to use the BCS-PtDA | 54 | 46 | 25 |

| A majority, Almost All Colleagues, All Colleagues (%) | Half of Colleagues (%) | Not a Single Colleague, almost No Colleague, a Minority (%) | |

| Descriptive norm: proportion of colleagues that actually use the BCS-PtDA b | 67 | 17 | 17 |

| Determinants Associated with the Organization (i.e., hospital) | |||

| Totally Agree/ Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Totally Disagree/ Disagree (%) | |

| Time available: there is enough time available to integrate the BCS-PtDA as intended in my day-to-day work | 25 | 17 | 58 |

| Material resources and facilities: there are enough materials and facilities provided to use the BCS-PtDA as intended | 71 | 17 | 13 |

| Information accessible: it is easy for me to find information about using the BCS-PtDA as intended | 75 | 17 | 8 |

| Performance feedback: feedback is regularly provided about progress with the implementation of the BCS-PtDA | 50 | 21 | 29 |

| True | False | ||

| Formal ratification by management: there are formal arrangements relating the use of the BCS-PtDA c | 33 | 33 | |

| Coordinator: one or more people have been designated to coordinate the process of implementing the BCS-PtDA c | 88 | 4 | |

| Unsettled organization: there aren’t any other changes going on that could influence implementation of the BCS-PtDA a,c | 25 | 58 | |

| Median (Range) | |

|---|---|

| Frequency of screening | 25 (20–45) |

| Duration of post-treatment surveillance | 15 (0–30) |

| Type of screening examinations performed | 25 (0–45) |

| In-person consultation vs. receiving results over the telephone | 25 (0–50) |

| SDM STEP 1—CREATING CHOICE AWARENESS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Section A Accentuating that there is a choice and that it should be guided by patients’ preferences | “[When it comes to follow-up checks] you can make choices and we don’t want to steer you. It’s about you being aware of the risk [prognostic implications] and making a choice that suits you”. “Well, normally, by default, we do it [post-treatment surveillance] the same way for everyone. But not every person is the same and not every person has the same risk. That’s the reason we try to study if it makes sense to educate people [about their personalized risk]… so that they can then make their own personal consideration whether to adjust the follow-up, depending on their [personalized] risk, given their wishes…”. | |

| Section B Possible (implicit) steering due to framing of choice and referencing personal advice or guidelines | “Normally we [clinicians] always say about the first two years, come back every six months… Unless you would like otherwise”. “Based on this outcome [risk estimates from the INFLUENCE 2.0 nomogram], I recommend five years of monitoring. That means five years here at the hospital, with a mammogram and a physical examination annually. We check for a total of 10 years, only then [the latter five years] we do it through the family physician”. “Well, how do we deal with that [post-treatment surveillance] as doctors before the study [SHOUT-BC study]? We obviously have guidelines in the Netherlands that we adhere to. Guidelines are advice, advice to doctors. Well, the advice with breast cancer like you also had is, that you remain under surveillance for five years. That’s actually the advice. But I also have had people before this study opened, with whom I discussed this [personalizing post-treatment surveillance], not with these fancy numbers [risk estimates from INFLUENCE 2.0 nomogram]. … to whom I’ve also said, is there a point to the follow-up? And a number of people have said, well, thank you very much for operating on my breast, but I’ll see you when I feel something again. Of course, those are primarily elderly patients”. | |

| SDM STEP 2—INFORMATION PROVISION | ||

| Presentation of options | Section A Succinct presentation of options | Well, based on that [risk estimates from the INFLUENCE 2.0 nomogram] you can think, how often do I really have to actually come here [to the hospital]? Especially if that causes a lot of stress. Every year? Once every two years or maybe even less often? And the maximum period [of the post-treatment surveillance], in principle, five years. Or a shorter period? Do all the tests have to be done or can you do with a little less? The results you can get in the hospital or by phone. Those are the choices. |

| Communication of prognostic estimates | Section B Presentations of risk information—unclear which outcome is being discussed | You can see the graphic here. It shows 100 women with the same characteristics [as you]. Then you see that within five years after surgery, two out of 100, so 98 don’t get it [breast cancer] back. Two get the disease back. So the chances of not getting it [breast cancer] back are much higher. Then if you look at a hundred women, same age, et cetera. And look who of those got breast cancer again within five years, that’s three out of a hundred women, so 97 don’t get it back. … And then here you see the risks per year. So that’s around a one percent per year chance. And this [risk per year] always adds up. |

| Section C Discussion of aleatory uncertainty (i.e., inability to predict future events) | Well, in order to indicate a little bit what it could mean for you, we can also use statistics. We are fond of that [using statistics], aren’t we, in the medical world, to express everything in numbers. And, of course, it’s not like I have a crystal ball and can predict what will happen to you, but we can make an estimate, can’t we? | |

| SDM STEP 3 and 4—DELIBERATION AND DECISION-MAKING | ||

| Section A Discussion about current choice and potential for change of preference over time | Patient: Look, maybe if I know this longer [a longer period of time] that it’s [okay to have fewer check-up] then I might say oh well, maybe once every two years or so [is fine]. … HCP: Totally fine, totally fine. Patient: But maybe once I’ve processed it, that I’ll think like oh, well [less check-ups is okay] HCP: Exactly. And if maybe after two check-ups, you think well, it’s okay [no disease recurrence] for a second time, I feel a lot calmer about it all, then that [reconsidering frequency of check-ups] can be discussed. But so this [discussion] is really to make you aware [of the risk and the options]. | |

| Section B Deliberation about whether to opt for a telephone consultation to discuss the results | Patient: Yes. I’m not anxious, I’m very down-to-earth, but thinking about [whether to get a mammogram], then I want to know [whether the disease has recurred], if I can. HCP: Totally understandable, indeed. Now you indicated [on the BCS-PtDA summary sheet] that you want to get the results during a telephone consultation. Patient: Yes, that was fine by me, you know. HCP: But does that means that you don’t want a physical examination? So you keep track of that yourself [do breast self exams], or do you say, I want a physical examination as well? Because that part [of the post-treatment surveillance], if we annually discuss the results over the phone, means that the physical examination is dropped. So that might be something to think about, what you want. And then you say, I would like the health care provider to choose. That’s not what the decision aid is for, of course, precisely to ensure that you make your own choices. I can advise you, though. Patient: That’s what I mean. HCP: And again, the advice, I also put that at the top here, would be to at least check for five years with mammography and a physical examination. You may also do that physical examination at the doctor’s office. If you say, I monitor that very well myself and I’ll get in touch if I feel anything, that’s fine too. Patient: I never actually do that [breast self exams], I must admit. I don’t know what to feel for. I happened to feel this [the breast tumor] myself, but that was because it was just so noticeable… HCP: We can also do it together to see how skillful you can become in doing a breast exam. That I tell you what I’m doing and that I show you what to look for yourself. And if you say, I feel confident enough with that, then you do it yourself, and if that’s not the case, you just come here. Yes? Patient: Yes. HCP: Nice. I’m going to make a note of the choice you entered [on the BCS-PtDA summary sheet]. You can deviate from it [your choices] at any time. If at some point you say, but I’d like an extra check or I’d like to skip a check, that’s always good. It’s about doing what makes you happy. As long as we communicate about that with each other, that’s the most important thing. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ankersmid, J.W.; Engelhardt, E.G.; Lansink Rotgerink, F.K.; The, R.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Siesling, S.; van Uden-Kraan, C.F., on behalf of the Santeon VBHC Breast Cancer Group. Evaluation of the Implementation of the Dutch Breast Cancer Surveillance Decision Aid including Personalized Risk Estimates in the SHOUT-BC Study: A Mixed Methods Approach. Cancers 2024, 16, 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071390

Ankersmid JW, Engelhardt EG, Lansink Rotgerink FK, The R, Strobbe LJA, Drossaert CHC, Siesling S, van Uden-Kraan CF on behalf of the Santeon VBHC Breast Cancer Group. Evaluation of the Implementation of the Dutch Breast Cancer Surveillance Decision Aid including Personalized Risk Estimates in the SHOUT-BC Study: A Mixed Methods Approach. Cancers. 2024; 16(7):1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071390

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnkersmid, Jet W., Ellen G. Engelhardt, Fleur K. Lansink Rotgerink, Regina The, Luc J. A. Strobbe, Constance H. C. Drossaert, Sabine Siesling, and Cornelia F. van Uden-Kraan on behalf of the Santeon VBHC Breast Cancer Group. 2024. "Evaluation of the Implementation of the Dutch Breast Cancer Surveillance Decision Aid including Personalized Risk Estimates in the SHOUT-BC Study: A Mixed Methods Approach" Cancers 16, no. 7: 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071390

APA StyleAnkersmid, J. W., Engelhardt, E. G., Lansink Rotgerink, F. K., The, R., Strobbe, L. J. A., Drossaert, C. H. C., Siesling, S., & van Uden-Kraan, C. F., on behalf of the Santeon VBHC Breast Cancer Group. (2024). Evaluation of the Implementation of the Dutch Breast Cancer Surveillance Decision Aid including Personalized Risk Estimates in the SHOUT-BC Study: A Mixed Methods Approach. Cancers, 16(7), 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071390