The Cancer Patient Empowerment Program: A Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Psychological Distress in Cancer Survivors, with Insights from a Mixed-Model Analysis, Including Implications for Breast Cancer Patients

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exposure

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Prognostic Covariates

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

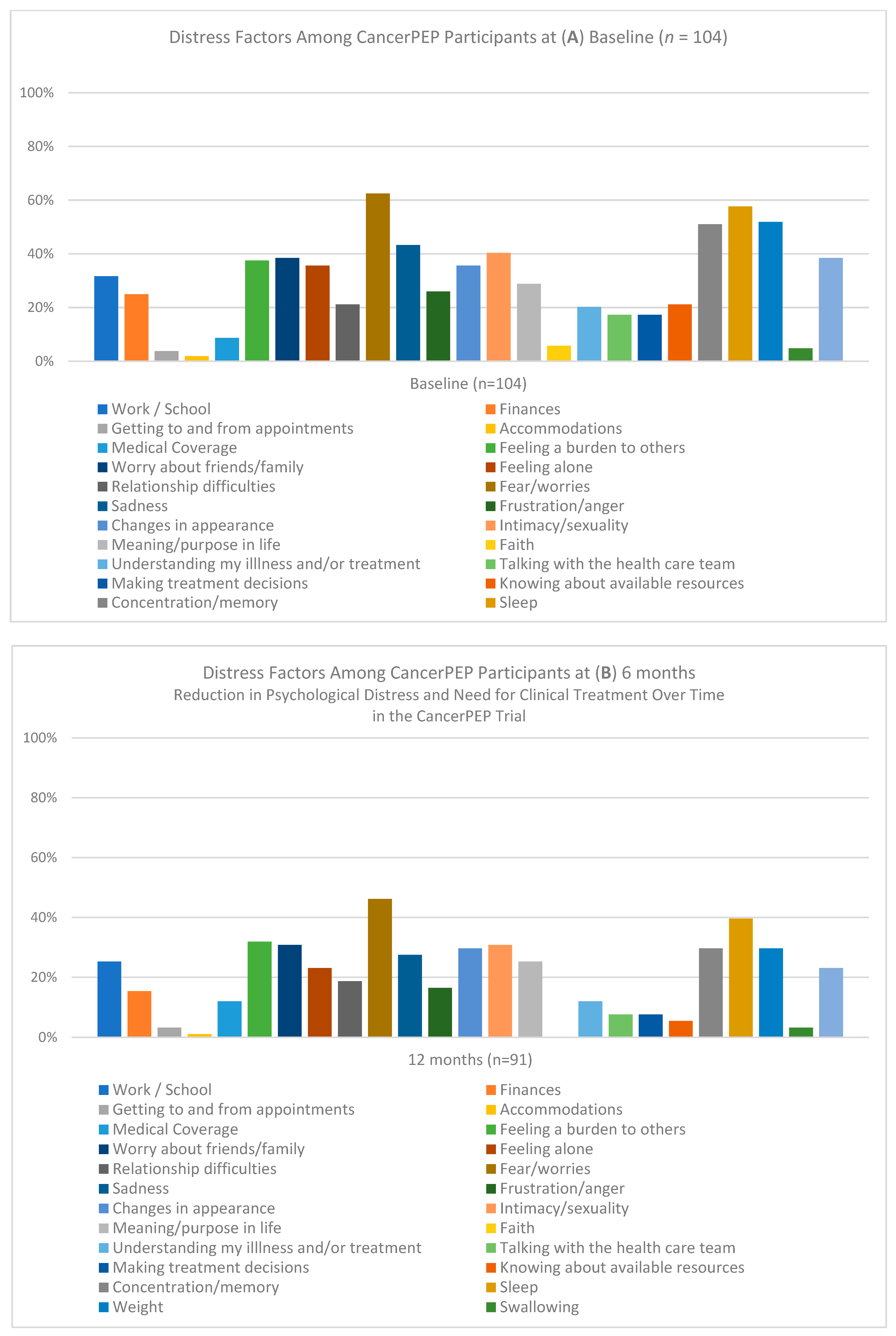

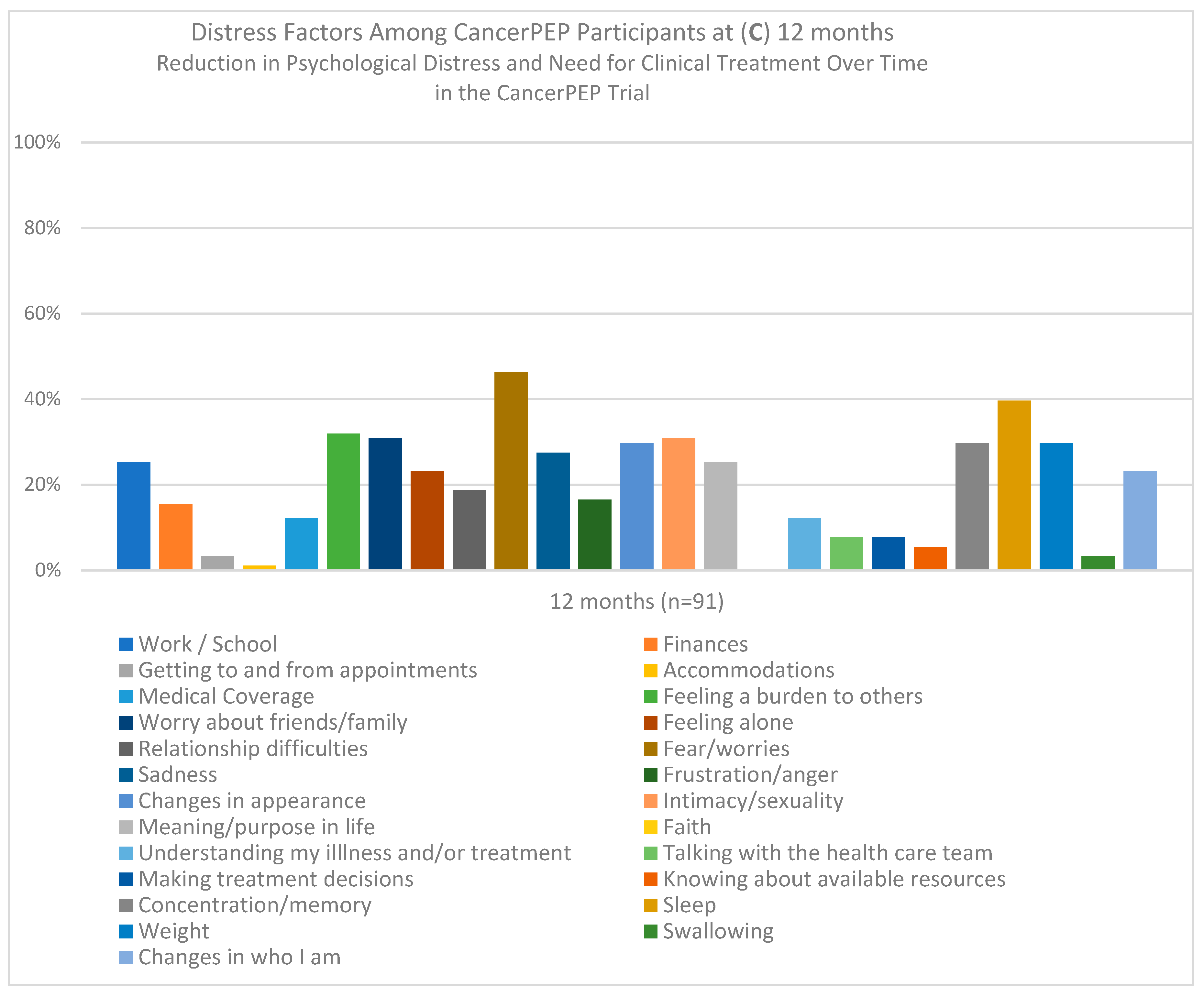

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility and Accrual

3.2. Attrition

3.3. Safety

3.4. Baseline Characteristics

3.5. Logistic Regression Analysis

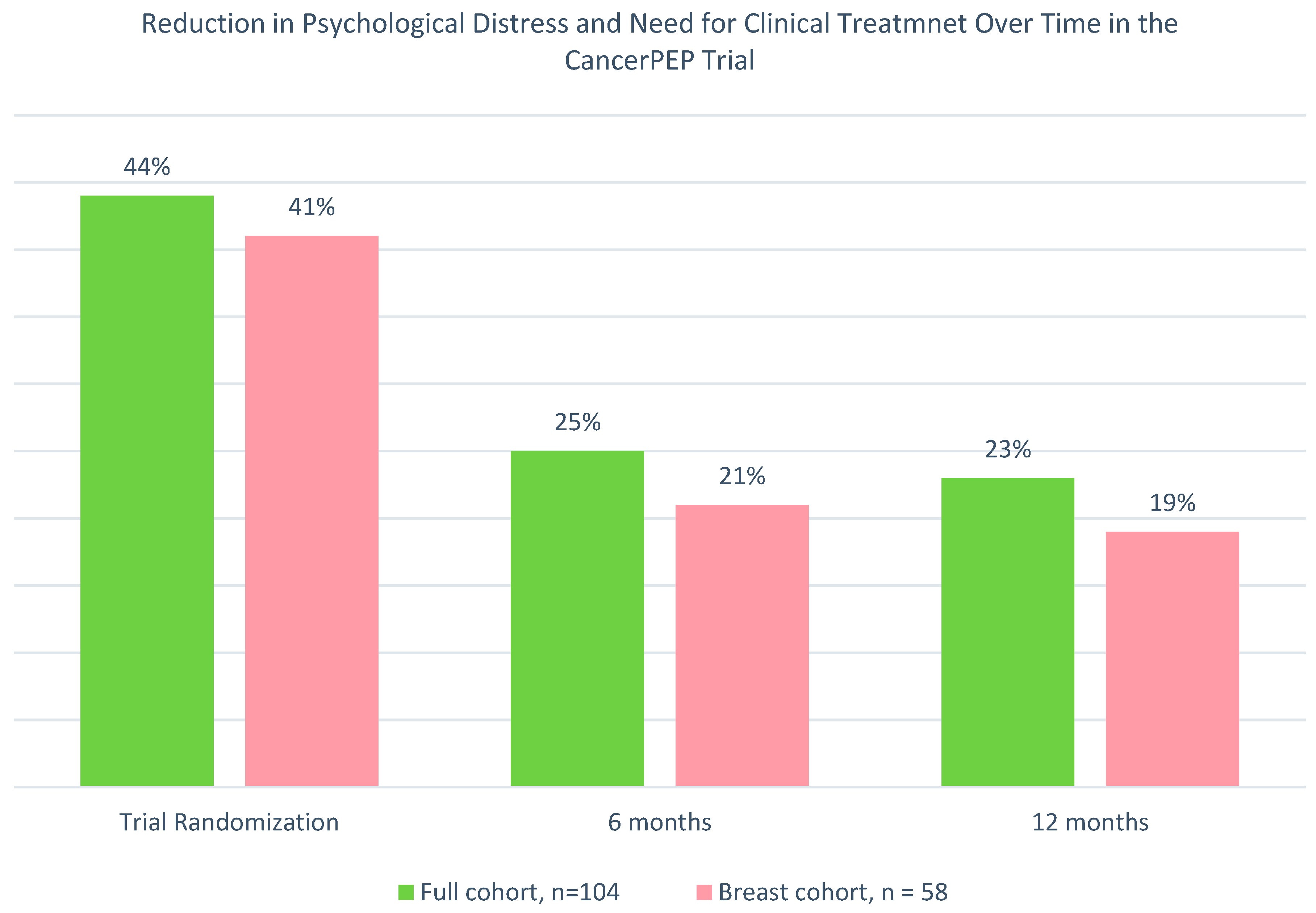

3.6. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) Analysis for the Full Sample

3.7. GEE Sub-Analysis for the Breast Cancer Cohort

3.8. Mixed-Model Analysis for the Full Sample

3.9. Mixed-Model Analysis for the Breast Cancer Subsample

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of CancerPEP in Reducing Psychological Distress

4.2. The Role of the HRV Biofeedback Monitor

4.3. Implications for Cancer Survivorship Care

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikhile, D.; Ford, E.; Glass, D.; Gremesty, G.; van Marwijk, H. A systematic review of risk factors associated with depression and anxiety in cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.R.; Gillis, J.; Demers, A.A.; Ellison, L.F.; Billette, J.M.; Zhang, S.X.; Liu, J.L.; Woods, R.R.; Finley, C.; Fitzgerald, N.; et al. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2024. CMAJ 2024, 196, E615–E623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Society. Mental Health and Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://cancer.ca (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Walker, J.; Holm Hansen, C.; Martin, P.; Sawhney, A.; Thekkumpurath, P.; Beale, C.; Symeonides, S.; Wall, L.; Murray, G.; Sharpe, M. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhadi, O. The impact of psychological distress on quality of care and access to mental health services in cancer survivors. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1111677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murnaghan, S.; Scruton, S.; Urquhart, R. Psychosocial interventions that target adult cancer survivors’ reintegration into daily life after active cancer treatment: A scoping review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 607–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, G.; Rendon, R.; Mason, R.; MacDonald, C.; Kucharczyk, M.J.; Patil, N.; Bowes, D.; Bailly, G.; Bell, D.; Lawen, J.; et al. A comprehensive 6-month prostate cancer patient empowerment program decreases psychological distress among men undergoing curative prostate cancer treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. Urol. 2023, 83, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, C.; Ilie, G.; Kephart, G.; Rendon, R.; Mason, R.; Bailly, G.; Bell, D.; Patil, N.; Bowes, D.; Wilke, D.; et al. Mediating effects of self-efficacy and illness perceptions on mental health in men with localized prostate cancer: A secondary analysis of the prostate cancer patient empowerment program (PC-PEP) randomized controlled trial. Cancers 2024, 16, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNevin, W.; Ilie, G.; Rendon, R.; Mason, R.; Spooner, J.; Chedrawe, E.; Patil, N.; Bowes, D.; Bailly, G.; Bell, D.; et al. PC-PEP, a comprehensive daily six-month home-based patient empowerment program, leads to weight loss in men with prostate cancer: A secondary analysis of a clinical trial. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1667–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawen, T.; Ilie, G.; Mason, R.; Rendon, R.; Spooner, J.; Champion, E.; Davis, J.; MacDonald, C.; Kucharczyk, M.J.; Patil, N.; et al. Six-month prostate cancer empowerment program (PC-PEP) improves urinary function: A randomized trial. Cancers 2024, 16, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HeartMath. The Science of HeartMath. 14 August 2023. Available online: https://www.heartmath.com/science/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Zelen, M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J. Chronic Dis. 1974, 27, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.L.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Slade, T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kessler, R.C.; Slade, T.; Andrews, G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabora, J.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; Curbow, B.; Hooker, C.; Piantadosi, S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology 1987, 10, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Das-Munshi, J.; Brähler, E. Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care—A meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, M.J. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2004, 2004, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, J.C.; DeLongis, A. Going beyond social support: The role of social relationships in adaptation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 54, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebber, A.M.; Buffart, L.M.; Kleijn, G.; Riepma, I.C.; Bree, R.T.; Leemans, C.R.; Cuijpers, P. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P.J.; Lindblad, B.S. Clinical trials in cancer: How much control is needed? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 142, 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Adjustment for Baseline Covariates in Clinical Trials. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). 2015. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-adjustment-baseline-covariates-clinical-trials_en.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Adjusting for Covariates in Randomized Clinical Trials for Drugs and Biological Products: Draft Guidance for Industry; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/123801/download (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salsman, J.M.; Pustejovsky, J.E.; Schueller, S.M.; Hernandez, R.; Berendsen, M.; McLouth, L.E.S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Psychosocial interventions for cancer survivors: A meta-analysis of effects on positive affect. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, L.; Spiegel, D.; Riba, M. Advancing psychosocial care in cancer patients. F1000Research 2017, 6, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleisiaris, C.; Maniou, M.; Karavasileiadou, S.; Togas, C.; Konstantinidis, T.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Tsaras, K.; Almegewly, W.H.; Androulakis, E.; Alshehri, H.H. Psychological distress and concerns of in-home older people living with cancer and their impact on supportive care needs: An observational survey. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 9569–9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundle, R.; Afenya, E.; Agarwal, N. The effectiveness of psychological intervention for depression, anxiety, and distress in prostate cancer: A systematic review of literature. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021, 24, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.; Hibbard, J.; Tusler, M. How do people with different levels of activation self-manage their chronic conditions? Patient 2009, 2, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Funnell, M.M. Patient empowerment: Reflections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 57, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.; Sonet, E. Does patient activation level affect the cancer patient journey? Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1276–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, B.; Bergkvist, K.; Karlsson Rosenblad, A.; Sharp, L.; Bergenmar, M. Patients with low activation level report limited possibilities to participate in cancer care. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, E.B.; Frank, E. Physicians’ health practices strongly influence patient health practices. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2009, 39, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggi, E.; Baccini, M.; Camussi, E.; Gallo, F.; Anatrone, C.; Pezzana, A.; Senore, C.; Giordano, L. Promoting healthy lifestyle habits among participants in cancer screening programs: Results of the randomized controlled Sti.Vi study. J. Public Health Res. 2022, 11, 22799036221106542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuinman, M.A.; Nuver, J.; de Boer, A.; Looijmans, A.; Hagedoorn, M. Lifestyle changes after cancer treatment in patients and their partners: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Triandis, H.; Kanfer, F.H.; Becker, M.; Middlestadt, S.E.; Eichler, A. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change. In Handbook of Health Psychology; Baum, A.S., Revenson, T.A., Singer, J., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, G.; MacDonald, C.; Richman, H.; Rendon, R.; Mason, R.; Nuyens, A.; Bailly, G.; Bell, D.; Patil, N.; Bowes, D.; et al. Assessing the efficacy of a 28-day comprehensive online prostate cancer patient empowerment program (PC-PEP) in facilitating engagement of prostate cancer patients in their survivorship care: A qualitative study. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 8633–8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CancerPEP with Early HRV Device (n = 52) | CancerPEP with Late HRV Device (n = 52) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 52, 60 (52–69) | 52, 57 (51–61) | 0.013 |

| Sex 1 (female) | 52, 45, 87% | 52, 45, 87% | 1.00 |

| Menopause (menstrual period over one year ago) | 37, 82% | 28, 84% | 0.8 |

| Race | 52, 49, 94% | 52, 46, 89% | 0.7 |

| Sexual orientation, heterosexual | 52, 52, 100% | 52, 48, 92% | 0.4 |

| Body mass index | 52, 28 (23–32) | 52, 27 (23–30) | 0.2 |

| Household income, <$80,000 CAD/past year | 52, 15, 29% | 52, 11, 21% | 0.4 |

| Education, university or above | 52, 34, 65% | 55, 33, 64% | 0.8 |

| Employment status (full- or part-time) | 52, 30, 58% | 52, 27, 52% | 0.6 |

| Relationship status (married/currently in relationship) | 52, 45, 87% | 52, 43, 83% | 0.6 |

| Living | 0.047 | ||

| Rural | 6, 12% | 14, 27% | |

| Urban | 46, 88% | 38, 73% | |

| Province | 0.6 | ||

| Nova Scotia | 9, 17% | 8, 15% | |

| New Brunswick | 0, 0% | 2, 4% | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1, 2% | 3, 6% | |

| Quebec | 1, 2% | 1, 2% | |

| Ontario | 26, 50% | 27, 52% | |

| Manitoba | 0, 0% | 1, 2% | |

| Saskatchewan | 4, 8% | 5, 10% | |

| Alberta | 7, 13% | 4, 7% | |

| British Columbia | 4, 8% | 1, 2% | |

| Screening positive for nonspecific psychological distress and need for clinical treatment (K10 ≥ 20) | 52, 20, 39% | 52, 24, 46% | 0.4 |

| Stage of cancer | 0.5 | ||

| I | 14, 27% | 10, 19% | |

| II or III | 18, 35% | 25, 48% | |

| IV | 13, 25% | 13, 25% | |

| Unknown | 7, 13% | 4, 8% | |

| Type of cancer | 0.108 | ||

| Bladder cancer | 1, 2% | 2, 4% | |

| Blood cancer | 9, 17% | 5, 10% | |

| Breast cancer | 27, 52% | 31, 59% | |

| Gynecological cancers (cervical, endometrial, ovarian, uterine) | 4, 8% | 3, 6% | |

| Colon or colorectal | 6, 11% | 1, 2% | |

| Kidney cancer | 4, 8% | 2, 4% | |

| Lung cancer | 0, 0% | 6, 11% | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0, 0% | 1, 2% | |

| Skin cancer or melanoma | 1, 2% | 1, 2% | |

| Months between first cancer diagnosis and trial start | 49, 27 (17, 58) | 46, 30 (11, 34) | 0.6 |

| Metastasis present at trial start | 3, 5.8% | 3, 5.8 | 1.0 |

| Treatment modality | 0.7 | ||

| Surgery ± radiation, hormone, and/or chemotherapy | 41, 79% | 39, 75% | |

| Radiation ± hormone (endocrine) therapy and/or chemotherapy | 3, 6% | 5, 10% | |

| Chemotherapy ± hormone (endocrine) therapy | 8, 15% | 8, 15% | |

| Multi-morbidities | 0.6 | ||

| One (other than the cancer diagnosis) | 18, 35% | 22, 42% | |

| Two | 14, 27% | 15, 29% | |

| Three or more | 20, 38% | 15, 29% | |

| Self-identified as a tobacco user | 0, 0% | 0, 0% | 0.9 |

| Currently using tobacco | 0, 0% | 0, 0% | |

| Used tobacco daily in the past | 16, 30% | 15, 28% | |

| Used tobacco less than daily in the past | 4, 8% | 3, 6% | |

| Never used tobacco | 32, 62% | 34, 66% | |

| Intake of prescribed medication for anxiety, depression, or both at the time of entry in the trial | 9, 17% | 12, 23% |

| A. | Presence of psychological distress and need for clinical treatment at 6 months aOR (95% CI) | p |

| Full cohort analysis a (n = 104) | <0.001 | |

| Group | ||

| CancerPEP without biofeedback HRV monitor provided | 1.0 Reference | |

| CancerPEP with biofeedback HRV monitor provided | 0.72 (0.19, 2.69) | 0.6 |

| Psychological distress (K10) baseline | 1.33 (1.15, 1.55) | <0.001 |

| Partial cohort analysis a (n = 58; breast cancer patients only) | <0.001 | |

| Group | ||

| CancerPEP without biofeedback HRV monitor provided | 1.0 Reference | |

| CancerPEP with biofeedback HRV monitor provided | 0.39 (0.05, 3.13) | 0.4 |

| Psychological distress (K10) baseline | 1.54 (1.15, 2.08) | 0.004 |

| B. | Presence of psychological distress and need for clinical treatment at 12 months aOR (95% CI) | p |

| Full cohort analysis (n = 104) | 0.002 | |

| Group | ||

| CancerPEP with late (at 6 mo. after trial start) provision of biofeedback HRV monitor | 1.0 Reference | |

| CancerPEP with early (at trial start) provision of biofeedback HRV monitor | 1.14 (0.30, 4.39) | 0.8 |

| Psychological distress (K10) baseline | 1.28 (1.11, 1.47) | <0.001 |

| Partial cohort analysis (n = 58; breast cancer patients only) | 0.010 | |

| Group | ||

| CancerPEP with late (at 6 mo. after trial start) provision of biofeedback HRV monitor | 1.0 Reference | |

| CancerPEP with early (at trial start) provision of biofeedback HRV monitor | 0.24 (0.03, 1.98) | 0.19 |

| Psychological distress (K10) baseline | 1.22 (1.02, 1.45) | 0.028 |

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | Wald χ² | df | p-Value | OR | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −3.26 | 1.36 | [−5.92, −0.61] | 5.79 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.04 | [0.003, 0.55] |

| Time | 18.13 | 2 | <0.001 | |||||

| Time 1 vs. Time 3 | 1.08 | 0.30 | [0.49, 1.67] | 12.72 | 1 | <0.001 | 2.94 | [1.62, 5.30] |

| Time 1 vs. Time 2 | 0.97 | 0.28 | [0.42, 1.52] | 12.14 | 1 | <0.001 | 2.64 | [1.53, 4.56] |

| Time 2 vs. Time 3 | 0.11 | 0.33 | [−0.53, 0.75] | 0.11 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.11 | [0.59, 2.11] |

| Group randomization | 0.57 | 0.38 | [−0.16, 1.31] | 2.33 | 1 | 0.13 | 1.77 | [0.85, 3.70] |

| Patient age | −0.003 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.027 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.99 | [0.96, 1.04] |

| Comorbidities | 0.39 | 0.23 | [−0.05, 0.83] | 3.011 | 1 | 0.083 | 1.48 | [0.95, 2.29] |

| Relationship status | 0.16 | 0.49 | [−0.80, 1.12] | 0.11 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.17 | [0.45, 3.07] |

| Treatment type | −0.06 | 0.25 | [−0.56, 0.44] | 0.057 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.94 | [0.57, 1.55] |

| Prescribed intake of medication for anxiety, depression, or both | 1.23 | 0.47 | [0.31, 2.15] | 6.88 | 1 | 0.009 | 3.42 | [1.36, 8.55] |

| Months between diagnosis and enrollment | 0.003 | 0.003 | [−0.003, 0.01] | 1.18 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.01] |

| Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | Wald χ² | df | p-Value | OR | 95% CI for OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −4.73 | 2.39 | [−9.41, −0.056] | 3.93 | 1 | 0.047 | 0.01 | [0.000082, 0.95] |

| Time | 11.53 | 2 | 0.003 | |||||

| Time 1 vs. Time 3 | 1.004 | 0.36 | [0.300, 1.71] | 7.82 | 1 | 0.005 | 2.73 | [1.35, 5.52] |

| Time 1 vs. Time 2 | 0.81 | 0.39 | [0.98,0.58] | 7.06 | 1 | 0.008 | 2.25 | [1.24, 4.08] |

| Time 2 vs. Time 3 | 0.19 | 0.39 | [−0.58, 0.98] | 0.24 | 1 | 0.6 | 1.22 | [0.56, 2.65] |

| Group randomization | 1.10 | 0.57 | [−0.020, 2.22] | 3.70 | 1 | 0.054 | 3.07 | [0.98, 9.23] |

| Patient age | 0.026 | 0.033 | [−0.036, 0.088] | 0.66 | 1 | 0.4 | 1.03 | [0.96, 1.09] |

| Comorbidities | 0.42 | 0.34 | [−0.24, 1.08] | 1.56 | 1 | 0.2 | 1.52 | [0.79, 2.94] |

| Relationship status (currently in a relationship) | −0.020 | 0.69 | [−1.37, 1.33] | 0.001 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.98 | [0.26, 3.78] |

| Treatment type | −0.60 | 0.57 | [−1.73, 0.53] | 1.093 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.55 | [0.18, 1.69] |

| Prescribed intake of medication for anxiety, depression, or both | 1.46 | 0.67 | [0.152, 2.771] | 4.78 | 1 | 0.029 | 4.31 | [1.16, 15.98] |

| Months between diagnosis and enrollment | −0.000011 | 0.007 | [−0.014, 0.014] | 0.000 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.00 | [0.99, 1.01] |

| Variable | B | SE | Wald χ² | df | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −1.68 | 1.05 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.108 | 0.19 | [0.024, 1.4] |

| Group (Late vs. Early HRV) | 0.58 | 0.305 | 3.7 | 1 | 0.056 | 1.8 | [0.99, 3.3] |

| Time 3 vs. Time 1 | −1.08 | 0.35 | 9.4 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.34 | [0.17, 0.68] |

| Time 2 vs. Time 1 | −0.99 | 0.35 | 8.1 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.37 | [0.19, 0.74] |

| Time 2 vs. Time 3 | 0.089 | 0.39 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.8 | 1.09 | [0.52, 2.3] |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.015 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.99 | [0.97, 1.03] |

| Comorbidities | 0.36 | 0.17 | 4.2 | 1 | 0.041 | 1.4 | [1.02, 2.004] |

| Relationship status (currently in a relationship) | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | [0.504, 2.7] |

| Prescribed intake of medication for anxiety, depression, or both | 1.23 | 0.36 | 12 | 1 | <0.001 | 3.4 | [1.7, 6.9] |

| Months between diagnosis and enrollment | 0.003 | 0.0028 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.2 | 1.003 | [0.99, 1.009] |

| Treatment type | −0.062 | 0.21 | 0.092 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.94 | [0.63,1.4] |

| Variable | B | SE | Wald χ² | df | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −2.6 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.104 | 0.073 | [0.003, 1.7] |

| Group (Late vs. Early HRV) | 1.1 | 0.43 | 6.9 | 1 | 0.009 | 3.11 | [1.3, 7.2] |

| Time 3 vs. Time 1 | −1.02 | 0.47 | 4.6 | 1 | 0.031 | 0.36 | [0.14, 0.91] |

| Time 2 vs. Time 1 | −0.87 | 0.47 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.062 | 0.42 | [0.17, 1.05] |

| Time 2 vs. Time 3 | 0.15 | 0.51 | 0.086 | 1 | 0.8 | 1.2 | [0.43, 3.1] |

| Age | 0.028 | 0.022 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.19 | 1.03 | [0.99, 1.07] |

| Comorbidities | 0.39 | 0.23 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.096 | 1.48 | [0.93, 2.3] |

| Relationship status (currently in a relationship) | 0.015 | 0.59 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.98 | 1.02 | [0.32, 3.3] |

| Prescribed intake of medication for anxiety, depression, or both | 1.5 | 0.49 | 9.1 | 1 | 0.003 | 4.5 | [1.69, 12] |

| Months between diagnosis and enrollment | 0.000 | 0.0052 | 0.008 | 1 | 0.93 | 1.0 | [0.99, 1.01] |

| Treatment type | −0.74 | 0.59 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.209 | 1.7 | [0.15, 1.5] |

| CancerPEP Intervention with HRV Device, n = 49 Responses Ranged from 0 (Not at All) to 10 (Extremely) | CancerPEP Intervention without HRV Device, n = 47 Responses Ranged from 0 (Not at All) to 10 (Extremely) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Participant-perceived competence of the CancerPEP Research and Clinical Team | 49 | 9.39 | 1.06 | 47 | 9.13 | 1.28 |

| Participant-rated likelihood of recommending the CancerPEP program to others who have been diagnosed with cancer | 49 | 9.41 | 1.22 | 47 | 9.17 | 1.55 |

| Participant-perceived importance of implementing CancerPEP as part of the standard of care for patients diagnosed with cancer, from the day of diagnosis | 49 | 9.00 | 1.53 | 47 | 9.00 | 1.55 |

| Participant’s interest in the CancerPEP program after first learning about it | 49 | 8.96 | 1.41 | 47 | 9.17 | 1.22 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the introduction/training videos at baseline | 49 | 8.33 | 1.74 | 47 | 8.09 | 1.73 |

| Participant-perceived overall usefulness of the CancerPEP program | 49 | 8.57 | 1.56 | 47 | 8.11 | 2.15 |

| Participant-perceived accessibility and quick response to inquiries throughout the trial from the CancerPEP research team and staff | 49 | 8.63 | 2.05 | 47 | 8.26 | 2.13 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s strength and aerobic exercises | 49 | 7.20 | 2.15 | 47 | 7.40 | 2.64 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s yoga videos and exercises (optional) | 21 | 6.81 | 2.46 | 32 | 7.31 | 2.52 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s dietary/nutrition advice and materials | 49 | 8.33 | 1.70 | 47 | 8.13 | 2.46 |

| Participant’s perceived lifestyle benefits at the end of 6 months compared to the start of the program (baseline) | 49 | 7.73 | 1.41 | 47 | 7.55 | 1.98 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s website, which included resources and program information | 49 | 7.94 | 2.08 | 47 | 7.74 | 2.35 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program to their partner (if applicable) during the 6 months | 49 | 6.41 | 3.39 | 47 | 6.43 | 3.54 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s daily videos with education and empowerment messages | 49 | 8.65 | 1.47 | 47 | 8.34 | 2.23 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s intimacy and connection education materials (videos and daily messages) | 49 | 7.04 | 2.14 | 47 | 7.15 | 2.81 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s healthy sleep habits component | 49 | 7.45 | 1.84 | 47 | 7.32 | 2.76 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s bi-weekly videoconference (if attended) | 39 | 7.15 | 2.55 | 33 | 7.42 | 2.46 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s stress reduction biofeedback device (HRV monitor) | 49 | 4.88 | 3.52 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s meditation videos | 49 | 7.37 | 2.44 | 47 | 7.49 | 2.75 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s Saturday weekly educational videos | 49 | 6.43 | 2.87 | 47 | 6.45 | 3.06 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of learning about habit formation and breaking bad habits | 49 | 7.98 | 1.51 | 47 | 7.32 | 2.89 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the teachings from the book Love is Letting Go of Fear | 48 | 6.42 | 2.70 | 46 | 6.50 | 3.16 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the Facebook group | 39 | 6.79 | 1.91 | 34 | 7.53 | 2.44 |

| Participant-perceived usefulness of the program’s Program Partner system (connection with 2 co-participants attending and going through the program at the same time and facing a similar cancer diagnosis and/or treatment) (optional program component) | 23 | 6.52 | 3.10 | 30 | 6.23 | 3.14 |

| Interest in continuing with the program after the 6 months | 49 | 30 | 61% | 47 | 36 | 77% |

| Participants’ interest in becoming a Mentor for the CancerPEP program | 49 | 11 | 22% | 47 | 16 | 34% |

| Participants’ interest in becoming a Research Citizen for the CancerPEP program | 49 | 24 | 49% | 47 | 15 | 32% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ilie, G.; Knapp, G.; Davidson, A.; Snow, S.; Dahn, H.M.; MacDonald, C.; Tsirigotis, M.; Rutledge, R.D.H. The Cancer Patient Empowerment Program: A Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Psychological Distress in Cancer Survivors, with Insights from a Mixed-Model Analysis, Including Implications for Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers 2024, 16, 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193373

Ilie G, Knapp G, Davidson A, Snow S, Dahn HM, MacDonald C, Tsirigotis M, Rutledge RDH. The Cancer Patient Empowerment Program: A Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Psychological Distress in Cancer Survivors, with Insights from a Mixed-Model Analysis, Including Implications for Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers. 2024; 16(19):3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193373

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlie, Gabriela, Gregory Knapp, Ashley Davidson, Stephanie Snow, Hannah M. Dahn, Cody MacDonald, Markos Tsirigotis, and Robert David Harold Rutledge. 2024. "The Cancer Patient Empowerment Program: A Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Psychological Distress in Cancer Survivors, with Insights from a Mixed-Model Analysis, Including Implications for Breast Cancer Patients" Cancers 16, no. 19: 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193373

APA StyleIlie, G., Knapp, G., Davidson, A., Snow, S., Dahn, H. M., MacDonald, C., Tsirigotis, M., & Rutledge, R. D. H. (2024). The Cancer Patient Empowerment Program: A Comprehensive Approach to Reducing Psychological Distress in Cancer Survivors, with Insights from a Mixed-Model Analysis, Including Implications for Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers, 16(19), 3373. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16193373