The Epidemiological Particularities of Malignant Hemopathies in French Guiana: 2005–2014

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. The Cancer Registry

2.2. Regrouping of Diagnoses

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Ethical and Regulatory Aspects

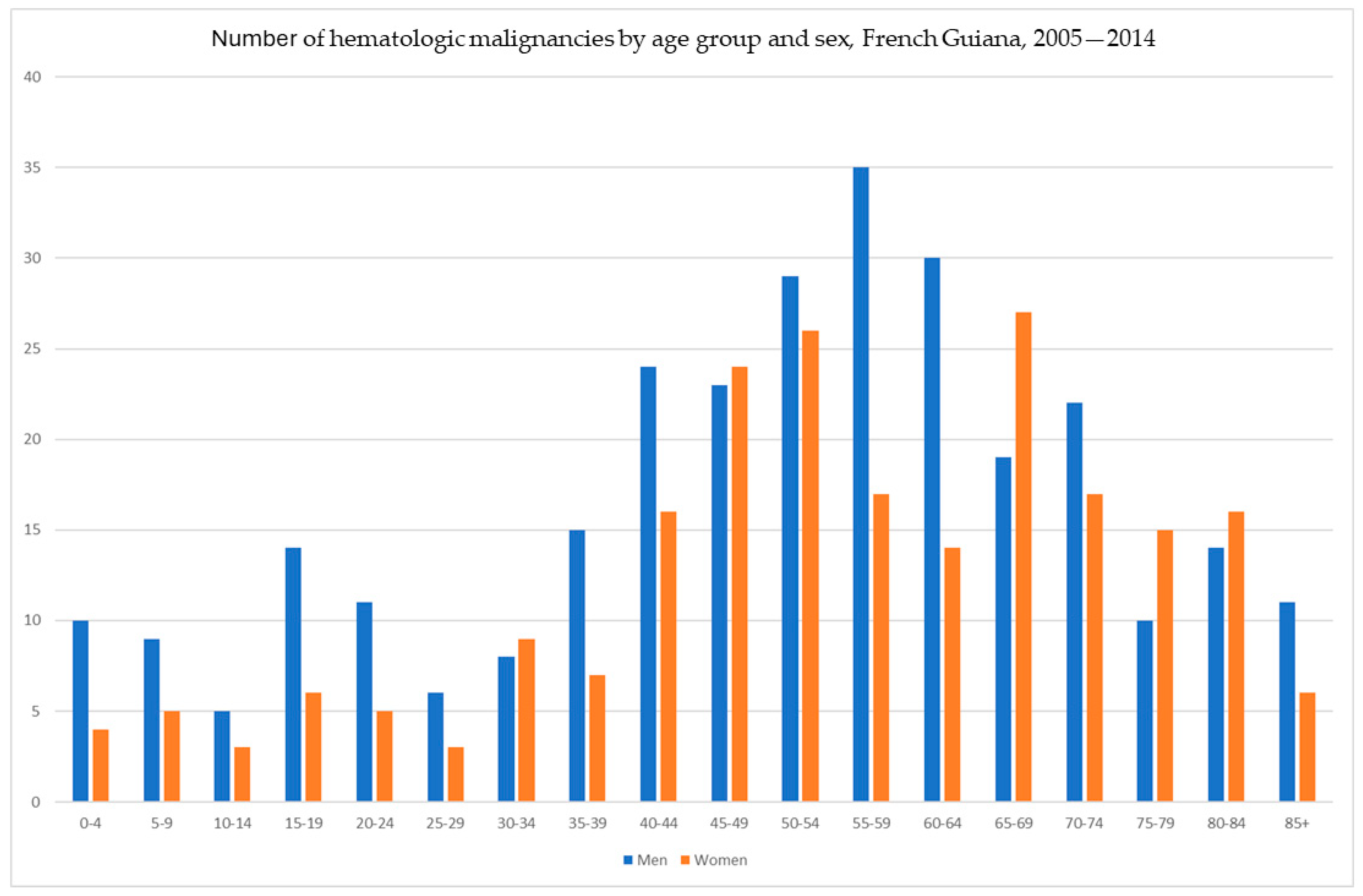

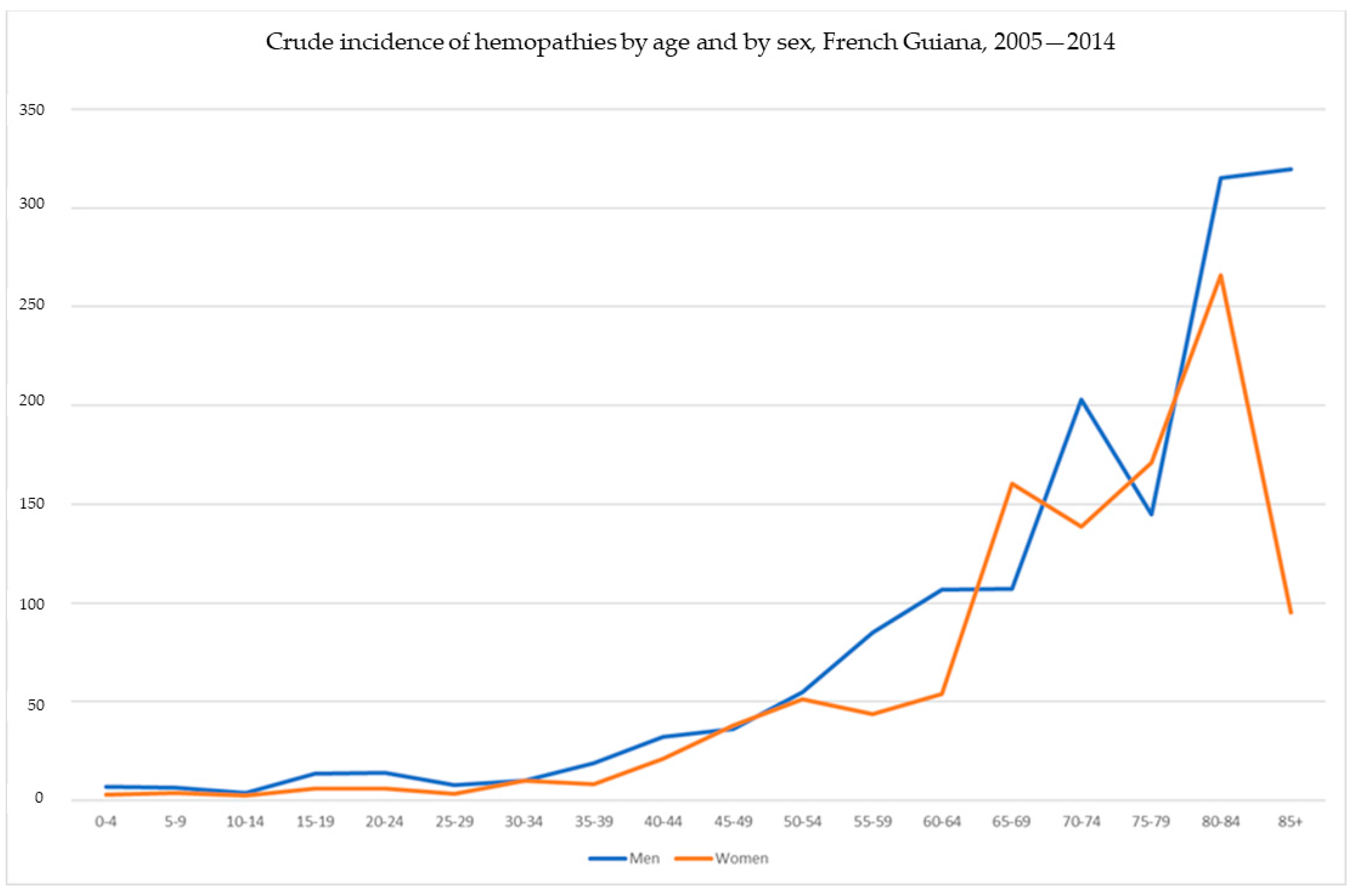

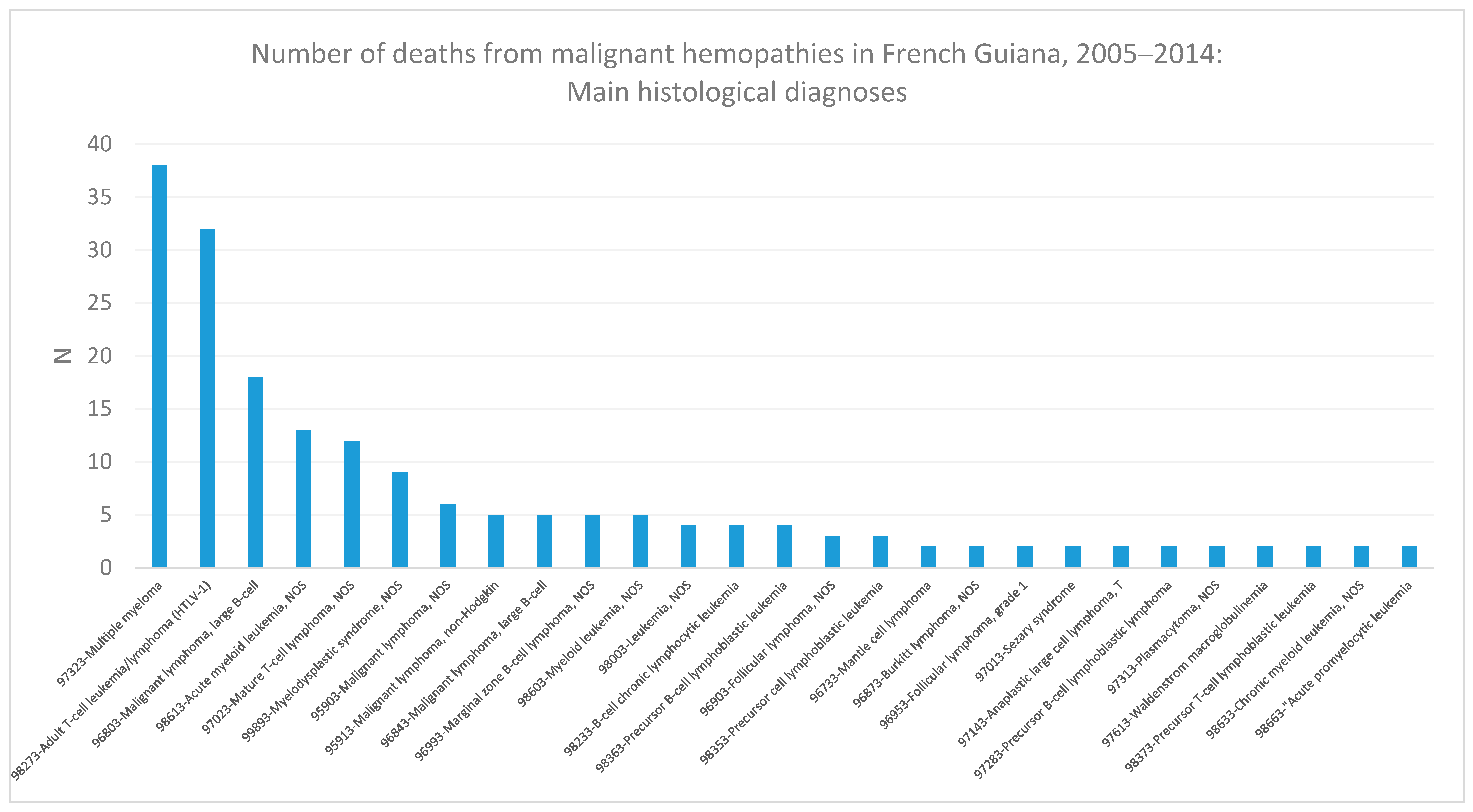

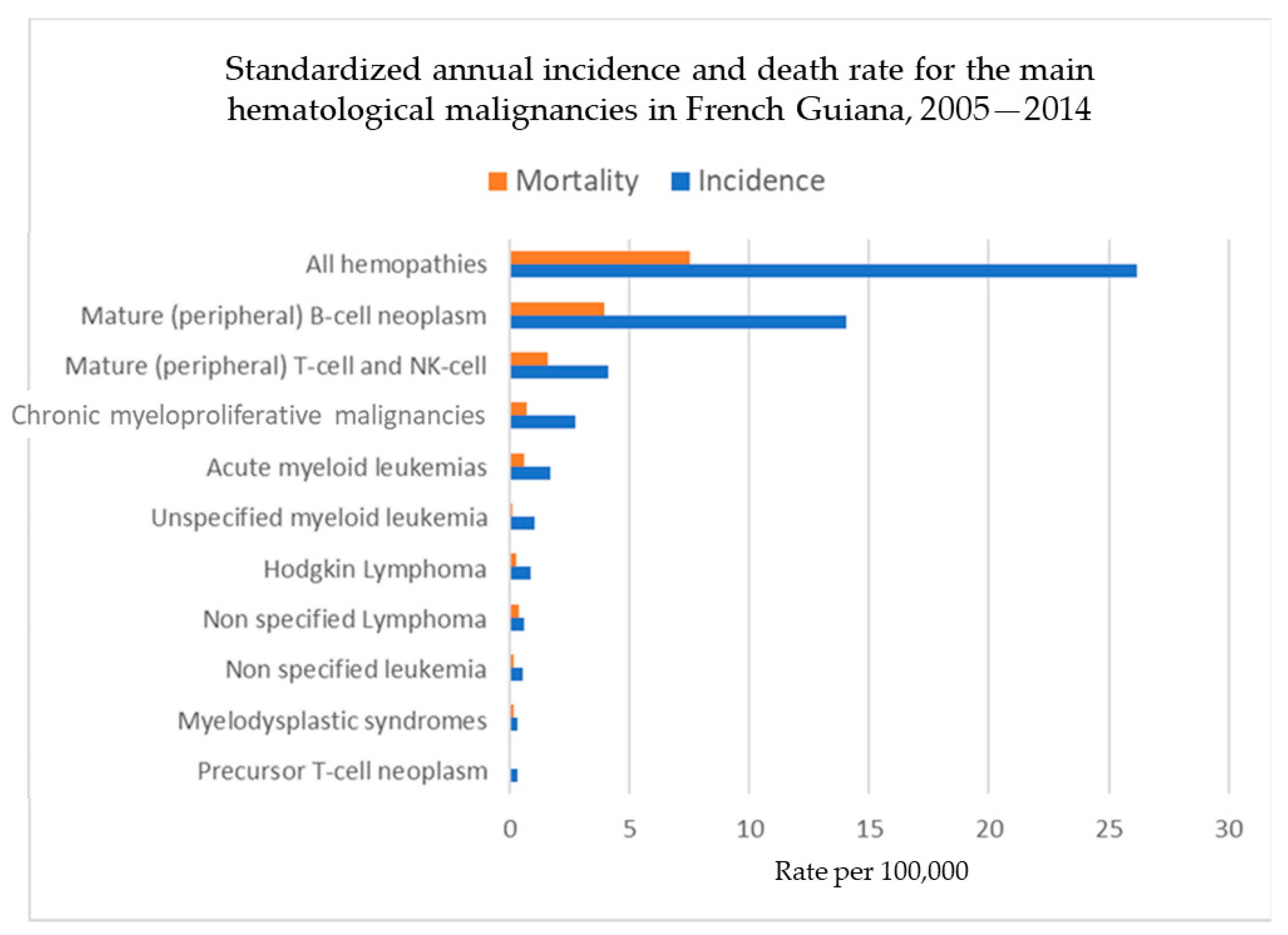

3. Results

3.1. Multiple Myeloma

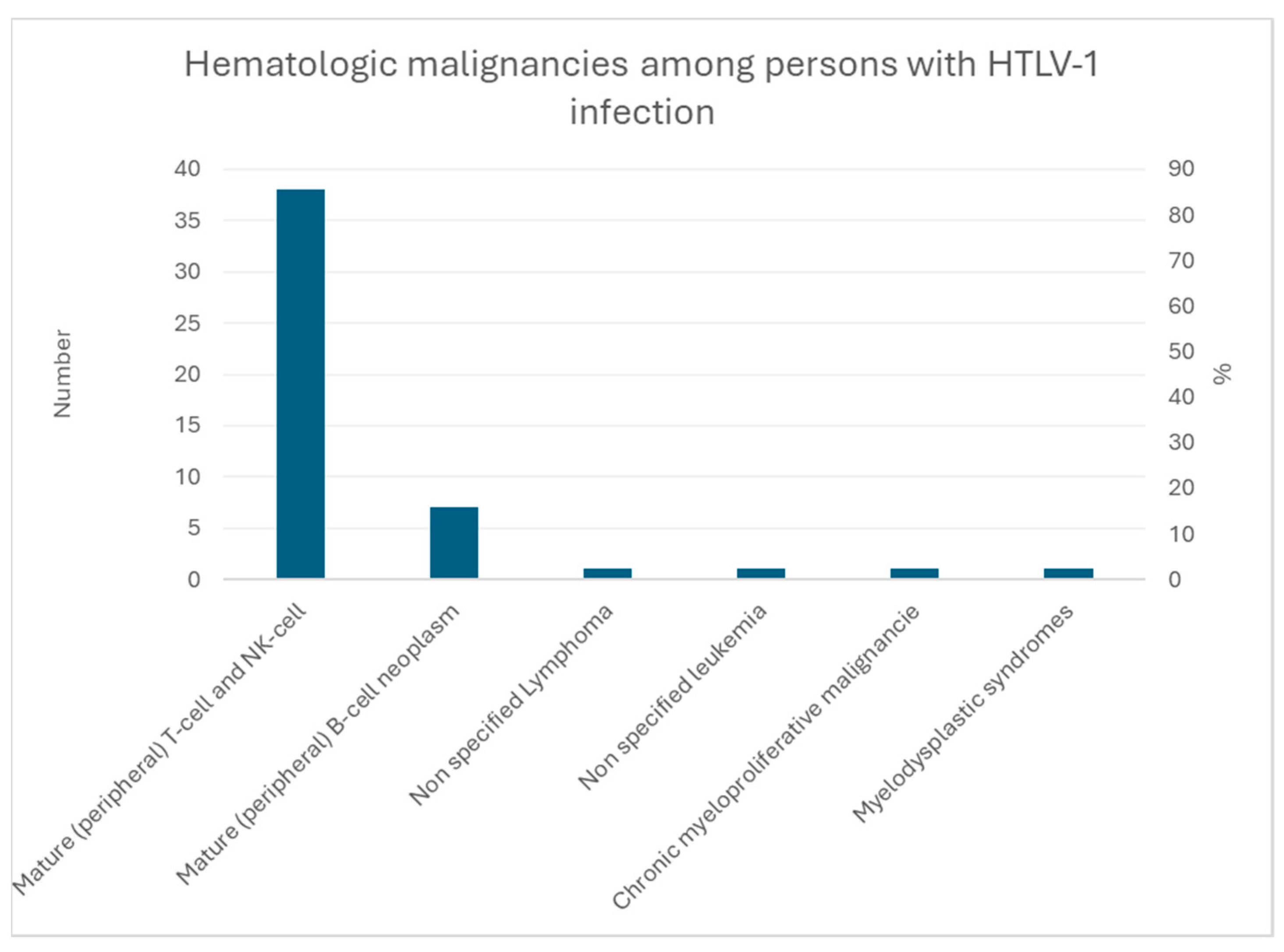

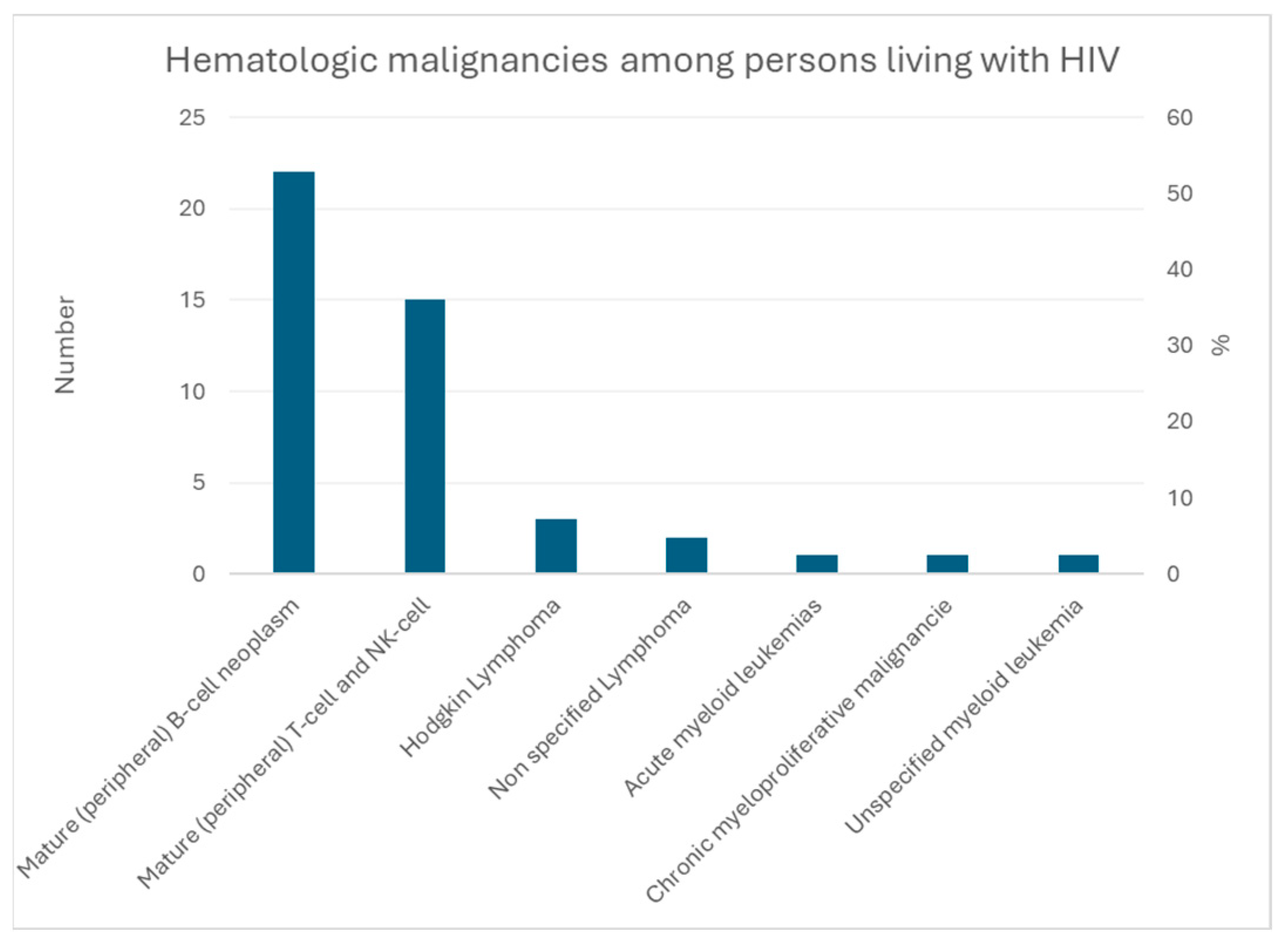

3.2. Mature T/NK-Cell Lymphoma

3.3. Adult T-Cell Lymphoma/Leukemia

3.3.1. Cofactors

3.3.2. Mortality

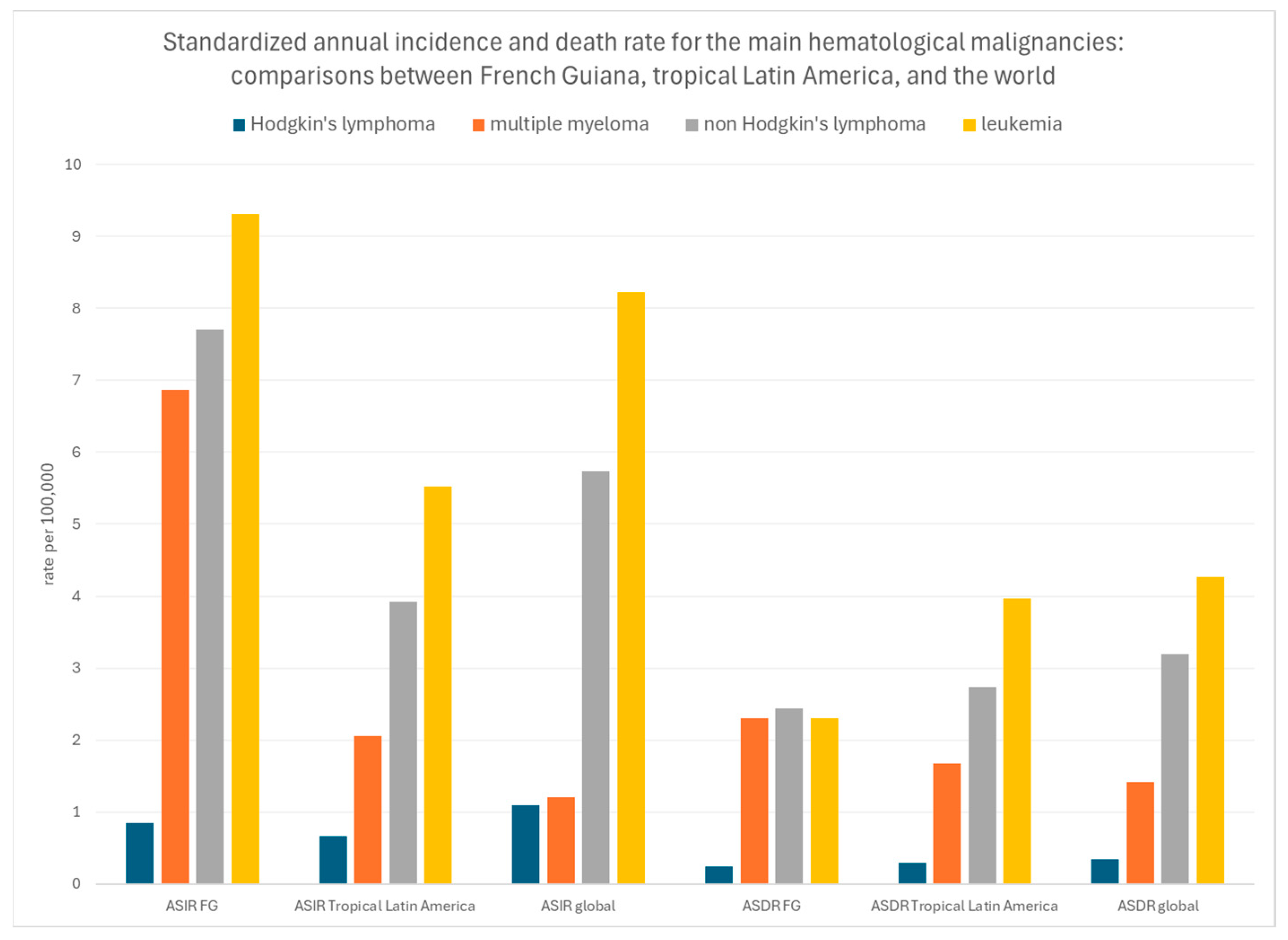

3.3.3. Standardized Incidence and Mortality Rates

3.3.4. Case Fatality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Article—Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire. Available online: http://beh.santepubliquefrance.fr/beh/2020/2-3/2020_2-3_1.html (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Abdelmoumen, K.; Alsibai, K.D.; Rabier, S.; Nacher, M.; Gessain, A.; Santa, F.; Hermine, O.; Marçais, A.; Couppié, P.; Droz, J.P.; et al. Adult T-cell leukemia and lymphoma in French Guiana: A retrospective analysis with real-life data from 2009 to 2019. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 21, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gessain, A.; Calender, A.; Strobel, M.; Lefait-Robin, R.; de Thé, G. High prevalence of antiHTLV-1 antibodies in the Boni, an ethnic group of African origin isolated in French Guiana since the 18th century. Comptes Rendus L’Acad. Sci. III 1984, 299, 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Plancoulaine, S.; Buigues, R.P.; Murphy, E.L.; van Beveren, M.; Pouliquen, J.F.; Joubert, M.; Rémy, F.; Tuppin, P.; Tortevoye, P.; De Thé, G.; et al. Demographic and familial characteristics of HTLV-1 infection among an isolated, highly endemic population of African origin in French Guiana. Int. J. Cancer 1998, 76, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliquen, J.-F.; Hardy, L.; Lavergne, A.; Kafiludine, E.; Kazanji, M. High seroprevalence of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 in blood donors in Guyana and molecular and phylogenetic analysis of new strains in the Guyana shelf (Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2020–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramassamy, J.-L.; Tortevoye, P.; Ntab, B.; Seve, B.; Carles, G.; Gaquière, D.; Madec, Y.; Fontanet, A.; Gessain, A. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma incidence rate in French Guiana: A prospective cohort of women infected with HTLV-1. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2044–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuppin, P.; Lepère, J.F.; Carles, G.; Ureta-Vidal, A.; Gérard, Y.; Peneau, C.; Tortevoye, P.; Moreau, J.P.; Gessain, A. Risk factors for maternal HTLV-I infection in French Guiana: High HTLV-I prevalence in the Noir Marron population. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. Off. Publ. Int. Retrovirol. Assoc. 1995, 8, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouhier, E.; Gaubert-Maréchal, E.; Abboud, P.; Couppié, P.; Nacher, M. Predictive factors of HTLV1-HIV coinfections in French Guiana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plancoulaine, S.; Abel, L.; van Beveren, M.; Gessain, A. High titers of anti-human herpesvirus 8 antibodies in elderly males in an endemic population. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 1333–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanji, M.; Dussart, P.; Duprez, R.; Tortevoye, P.; Pouliquen, J.; Vandekerkhove, J.; Couppié, P.; Morvan, J.; Talarmin, A.; Gessain, A. Serological and molecular evidence that human herpesvirus 8 is endemic among Amerindians in French Guiana. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 192, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plancoulaine, S.; Abel, L.; van Beveren, M.; Trégouët, D.-A.; Joubert, M.; Tortevoye, P.; de Thé, G.; Gessain, A. Human herpesvirus 8 transmission from mother to child and between siblings in an endemic population. Lancet 2000, 356, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malnati, M.S.; Dagna, L.; Ponzoni, M.; Lusso, P. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8/KSHV) and hematologic malignancies. Rev. Clin. Exp. Hematol. 2003, 7, 375–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guyane Française: Composition Ethnolinguistique. Available online: https://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/amsudant/guyanefr2.htm (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Coombs, C.C.; Falchi, L.; Weinberg, J.B.; Ferrajoli, A.; Lanasa, M.C. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in African Americans. Leuk. Lymphoma 2012, 53, 2326–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinstern, G.; Weinberg, J.B.; Parikh, S.A.; Braggio, E.; Achenbach, S.J.; Robinson, D.P.; Norman, A.D.; Rabe, K.G.; Boddicker, N.J.; Vachon, C.M.; et al. Polygenic risk score and risk of monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis in caucasians and risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in African Americans. Leukemia 2022, 36, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Colombet, M.; Ries, L.A.G.; Moreno, F.; Dolya, A.; Bray, F.; Hesseling, P.; Shin, H.Y.; Stiller, C.A.; IICC-3 contributors; et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001–2010: A population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.R.; Antillon-Klussmann, F.; Pei, D.; Yang, W.; Roberts, K.G.; Li, Z.; Devidas, M.; Yang, W.; Najera, C.; Lin, H.P.; et al. Association of Genetic Ancestry With the Molecular Subtypes and Prognosis of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imounga, L.M.; Alsibai, K.D.; Plenet, J.; Wang, Q.; Virjophe-Cenciu, B.; Couppie, P.; Sabbah, N.; Adenis, A.; Nacher, M. The Singular Epidemiology of Plasmacytoma and Multiple Myeloma in French Guiana. Cancers 2023, 16, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roué, T.; Labbé, S.; Belliardo, S.; Plenet, J.; Douine, M.; Nacher, M. Predictive factors of the survival of women with invasive breast cancer in French Guiana: The burden of health inequalities. Clin. Breast Cancer 2016, 16, e113–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estimations Régionales Et Départementales D’incidence et de Mortalité Par Cancers en France, 2007–2016—Guyane. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/regions/guyane/documents/rapport-synthese/2019/estimations-regionales-et-departementales-d-incidence-et-de-mortalite-par-cancers-en-france-2007-2016-guyane (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, F. Global burden of hematologic malignancies and evolution patterns over the past 30 years. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, S.; Patel, P.; Rondelli, D. Epidemiology, biology, and outcome in multiple myeloma patients in different geographical areas of the world. J. Adv. Intern. Med. 2012, 1, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, M.P.; Oliveira, M.M.; Silva, D.R.; Souza, D.L. Epidemiology of multiple myeloma in 17 Latin American countries: An update. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortevoye, P.; Tuppin, P.; Peneau, C.; Carles, G.; Gessain, A. Decrease of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I prevalence and low incidence among pregnant women from a high endemic ethnic group in French Guiana. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 87, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortevoye, P.; Tuppin, P.; Carles, G.; Peneau, C.; Gessain, A. Comparative trends of seroprevalence and seroincidence rates of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I and human immunodeficiency virus 1 in pregnant women of various ethnic groups sharing the same environment in French Guiana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 73, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Melle, A.; Cropet, C.; Parriault, M.-C.; Adriouch, L.; Lamaison, H.; Sasson, F.; Duplan, H.; Richard, J.-B.; Nacher, M. Renouncing care in French Guiana: The national health barometer survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valmy, L.; Gontier, B.; Parriault, M.C.; Van Melle, A.; Pavlovsky, T.; Basurko, C.; Grenier, C.; Douine, M.; Adenis, A.; Nacher, M. Prevalence and predictive factors for renouncing medical care in poor populations of Cayenne, French Guiana. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacher, M.; Adriouch, L.; Huber, F.; Vantilcke, V.; Djossou, F.; Elenga, N.; Adenis, A.; Couppié, P. Modeling of the HIV epidemic and continuum of care in French Guiana. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacher, M.; Basurko, C.; Douine, M.; Lambert, Y.; Rousseau, C.; Michaud, C.; Garlantezec, R.; Adenis, A.; Gomes, M.M.; Alsibai, K.D.; et al. Contrasted life trajectories: Reconstituting the main population exposomes in French Guiana. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1247310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

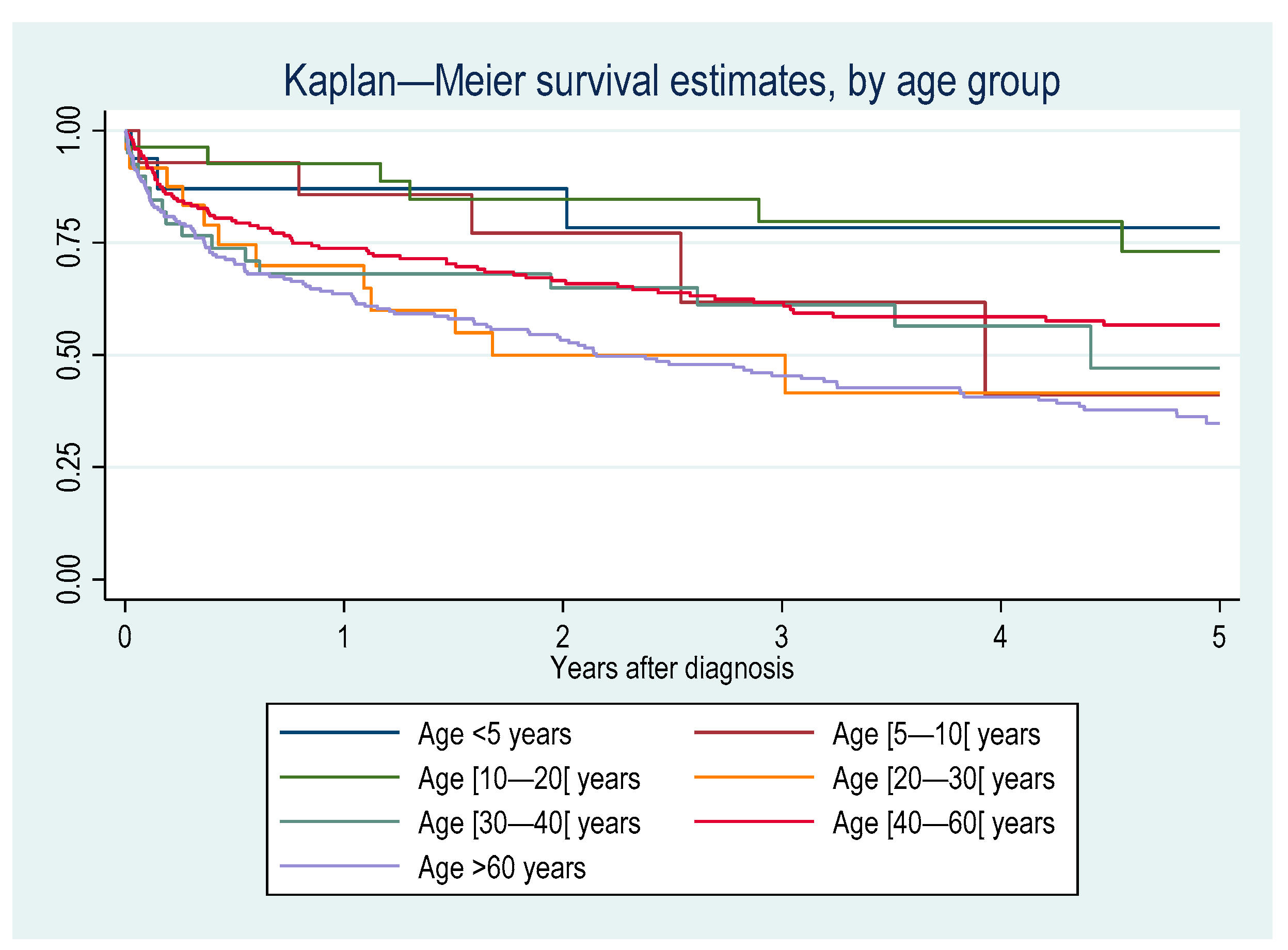

| Hazard Ratio | [95% CI] | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age category (years) | |||

| <5 | Reference | ||

| [5–10] | 4.58 | 0.88–23.79 | 0.07 |

| [10–20] | 2.19 | 0.45–10.75 | 0.34 |

| [20–30] | 4.93 | 1.10–22.10 | 0.04 |

| [30–40] | 5.30 | 1.20–23.42 | 0.03 |

| [40–60] | 4.78 | 1.16–19.67 | 0.03 |

| >60 | 8.16 | 2.00–33.33 | 0.00 |

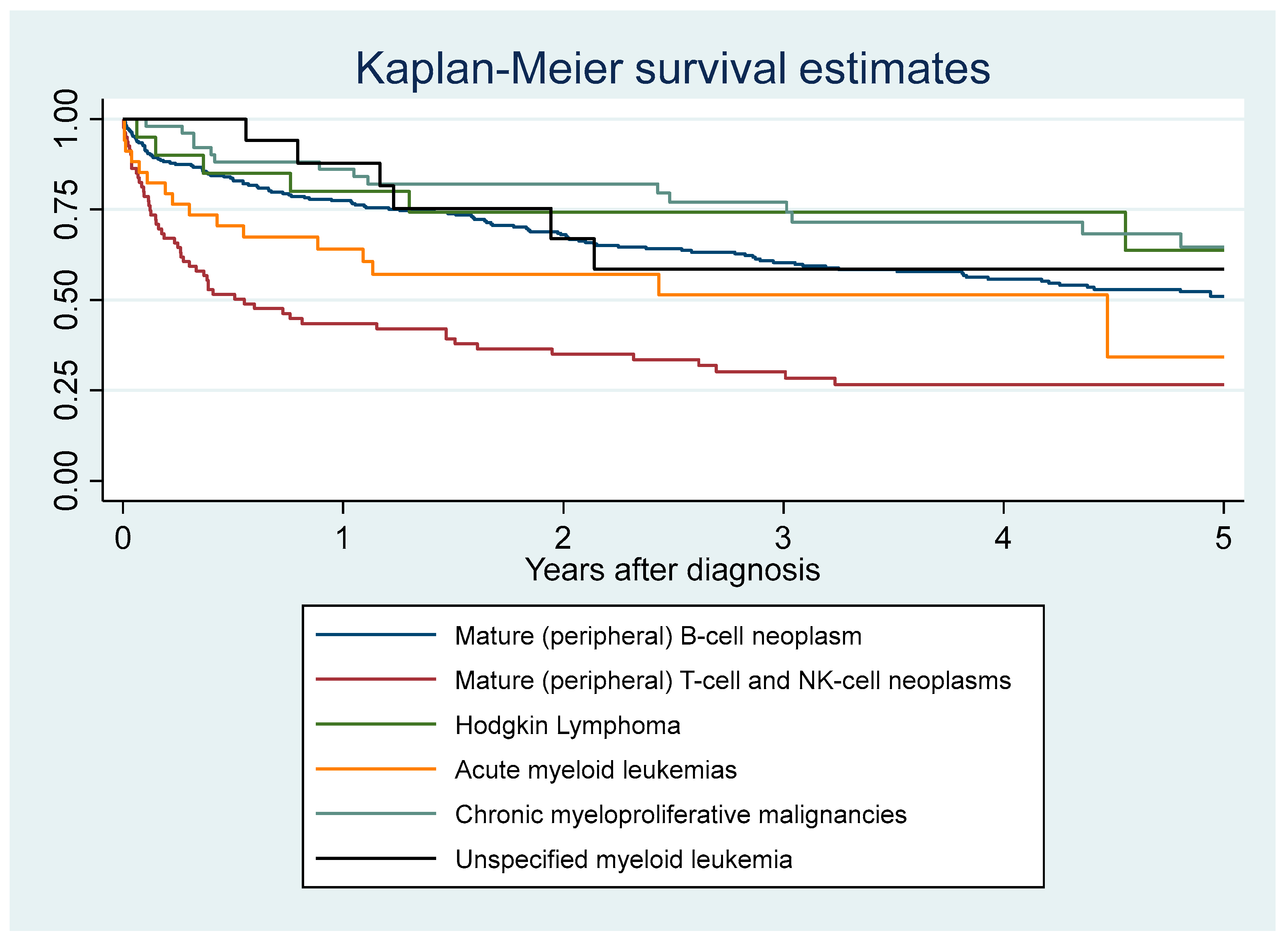

| Hemopathy | |||

| Mature (peripheral) B-cell neoplasm | Reference | ||

| Precursor T-cell neoplasm | 1.90 | 0.45–8.10 | 0.39 |

| Mature t-cell and NK-cell neoplasms | 2.47 | 1.81–3.36 | 0.00 |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1.06 | 0.51–2.18 | 0.88 |

| Non-specified lymphoma | 4.76 | 2.14–10.61 | 0.00 |

| Non-specified leukemia | 2.07 | 0.65–6.54 | 0.22 |

| Acute myeloid leukemias | 1.74 | 0.99–3.06 | 0.05 |

| Chronic myeloproliferative malignancies | 0.81 | 0.51–1.29 | 0.38 |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 1.49 | 0.55–4.07 | 0.44 |

| Unspecified myeloid leukemia | 0.76 | 0.33–1.73 | 0.51 |

| Origin | |||

| French from mainland France | Reference | ||

| French from another overseas territory | 1.11 | 0.59–2.09 | 0.74 |

| French from French Guiana | 1.51 | 0.90–2.53 | 0.12 |

| Foreigner | 1.94 | 1.17–3.22 | 0.01 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.77 | 0.60–0.99 | 0.04 |

| Type of residence | |||

| Village accessible by paved road | Reference | ||

| City | 1.55 | 0.96–2.51 | 0.07 |

| Village only accessible by boat or air | 2.51 | 1.16–2.44 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nacher, M.; Wang, Q.; Cenciu, B.; Aboikoni, A.; Santa, F.; Quet, F.; Vergeade, F.; Adenis, A.; Deschamps, N.; Drak Alsibai, K. The Epidemiological Particularities of Malignant Hemopathies in French Guiana: 2005–2014. Cancers 2024, 16, 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112128

Nacher M, Wang Q, Cenciu B, Aboikoni A, Santa F, Quet F, Vergeade F, Adenis A, Deschamps N, Drak Alsibai K. The Epidemiological Particularities of Malignant Hemopathies in French Guiana: 2005–2014. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112128

Chicago/Turabian StyleNacher, Mathieu, Qiannan Wang, Beatrice Cenciu, Alolia Aboikoni, Florin Santa, Fabrice Quet, Fanja Vergeade, Antoine Adenis, Nathalie Deschamps, and Kinan Drak Alsibai. 2024. "The Epidemiological Particularities of Malignant Hemopathies in French Guiana: 2005–2014" Cancers 16, no. 11: 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112128

APA StyleNacher, M., Wang, Q., Cenciu, B., Aboikoni, A., Santa, F., Quet, F., Vergeade, F., Adenis, A., Deschamps, N., & Drak Alsibai, K. (2024). The Epidemiological Particularities of Malignant Hemopathies in French Guiana: 2005–2014. Cancers, 16(11), 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112128