Patient-Reported Mobility, Physical Activity, and Bicycle Use after Vulvar Carcinoma Surgery

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments

2.2.1. EQ-5D-5L Questionnaire

2.2.2. SQUASH Questionnaire

2.2.3. GO-Bicycling Questionnaire

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

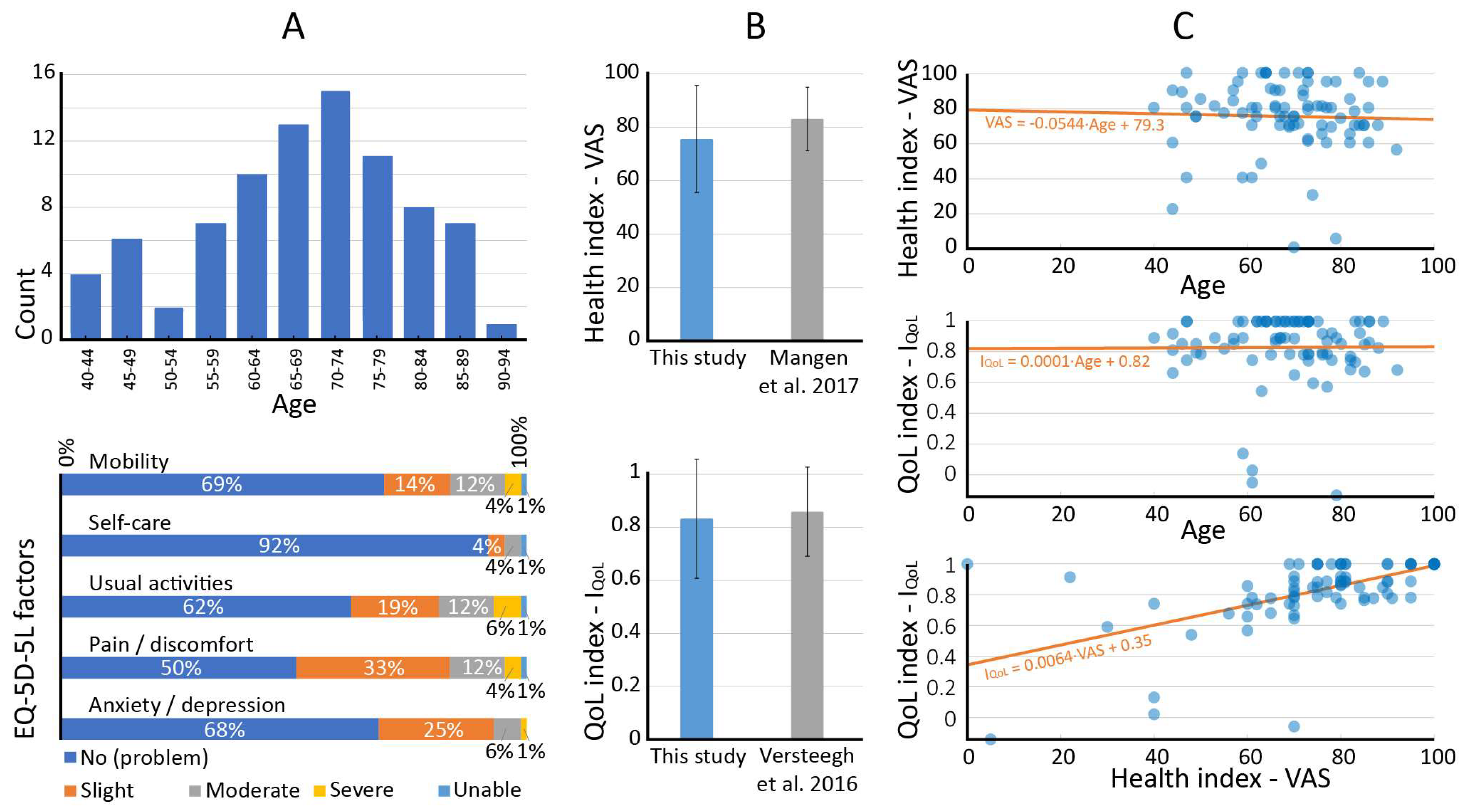

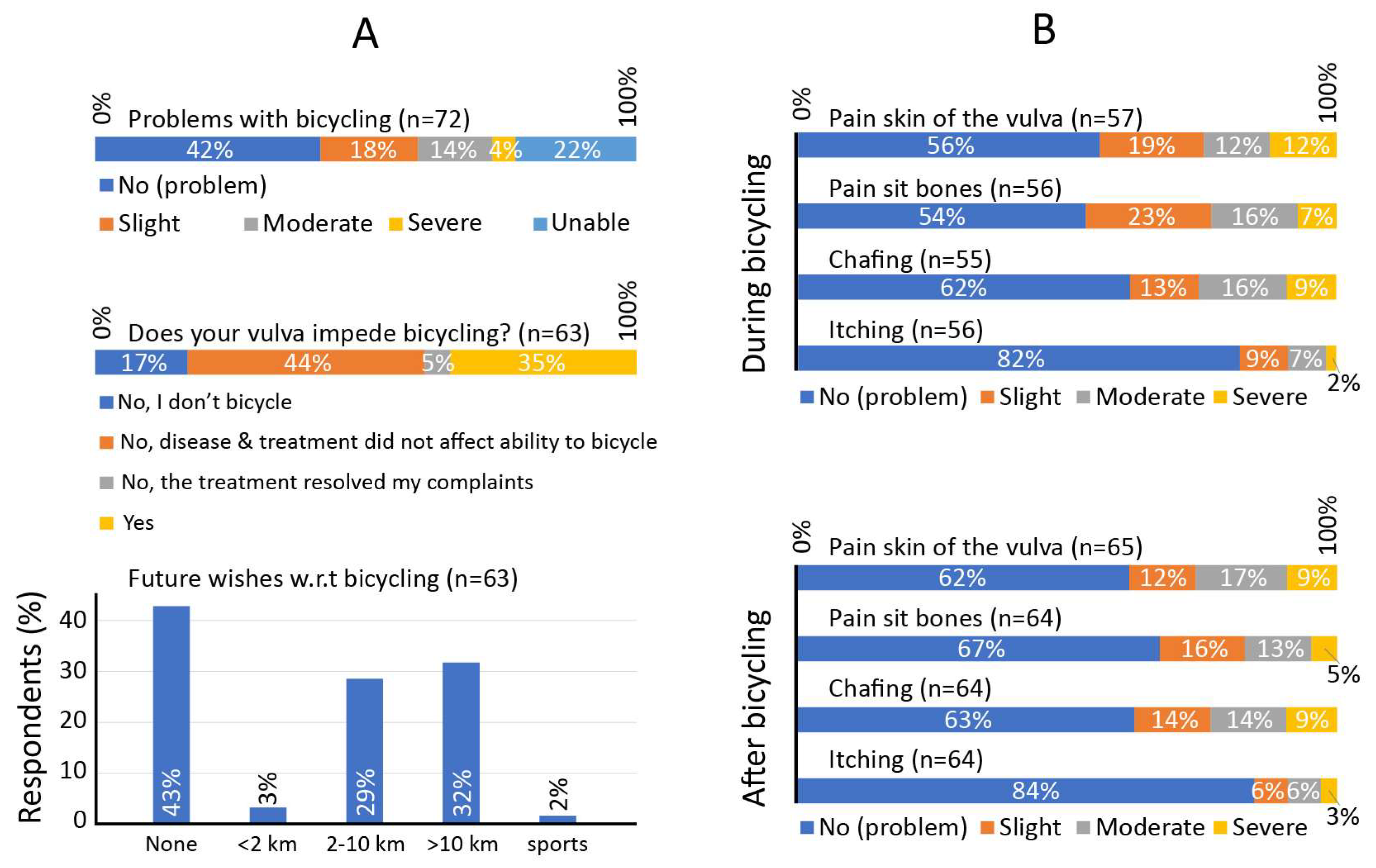

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Cycling for Everyone Lessons from Europe. Transport. Res. Rec. 2008, 2074, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Carstensen, T.A.; Wang, R.R.; Derrible, S.; Rueda, D.R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Liu, G. Historical patterns and sustainability implications of worldwide bicycle ownership and use. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.W.; Yuan, Y.F.; Van Oort, N.; Hoogendoorn, S. Bike-sharing systems’ impact on modal shift: A case study in Delft, the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Ziemke, D.; Nagel, K. Bicycle superhighway: An environmentally sustainable policy for urban transport. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 137, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Bauman, A.; de Geus, B.; Krenn, P.; Reger-Nash, B.; Kohlberger, T. Health benefits of cycling: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBS; RIVM. National Health Survey/Lifestyle Monitor; RIVM: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021.

- McTiernan, A.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Macko, R.; Buchner, D.; Pescatello, L.S.; Bloodgood, B.; Tennant, B.; Vaux-Bjerke, A.; et al. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2019, 51, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprod, L.K.; Mohile, S.G.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Janelsins, M.C.; Peppone, L.J.; Morrow, G.R.; Lord, R.; Gross, H.; Mustian, K.M. Exercise and Cancer Treatment Symptoms in 408 Newly Diagnosed Older Cancer Patients. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2012, 3, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.S.; Larsen, F.G.; Sorensen, F.F.; Hedegaard, M.; Stottrup, N.; Hansen, E.A.; Madeleine, P. The effect of saddle nose width and cutout on saddle pressure distribution and perceived discomfort in women during ergometer cycling. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 70, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versteegh, M.M.; Vermeulen, K.M.; Evers, S.M.A.A.; de Wit, G.A.; Prenger, R.; Stolk, E.A. Dutch Tariff for the Five-Level Version of EQ-5D. Value Health 2016, 19, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendel-Vos, G.C.W.; Schuit, A.J.; Saris, W.H.M.; Kromhout, D. Reproducibility and relative validity of the Short Questionnaire to Assess Health-enhancing physical activity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weggemans, R.M.; Backx, F.J.G.; Borghouts, L.; Chinapaw, M.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Koster, A.; Kremers, S.; van Loon, L.J.C.; May, A.; Mosterd, A.; et al. The 2017 Dutch Physical Activity Guidelines. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, R.; Monninkhof, E.M.; Peeters, P.H.M.; van Gils, C.H.; van den Bongard, D.H.J.G.; Wendel-Vos, G.C.W.; Zuithoff, N.P.A.; Verkooijen, H.M.; May, A.M. Physical activity levels of women with breast cancer during and after treatment, a comparison with the Dutch female population. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangen, M.J.; Bolkenbaas, M.; Huijts, S.M.; van Werkhoven, C.H.; Bonten, M.J.; de Wit, G.A. Quality of life in community-dwelling Dutch elderly measured by EQ-5D-3L. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.S.T.; Norheim, K.L.; Marandi, R.Z.; Hansen, E.A.; Madeleine, P. A field study investigating sensory manifestations in recreational female cyclists using a novel female-specific cycling pad. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Grootenhuis, N.C.; van der Zee, A.G.J.; van Doorn, H.C.; van der Velden, J.; Vergote, I.; Zanagnolo, V.; Baldwin, P.J.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; van Dorst, E.B.; Trum, J.W.; et al. Sentinel nodes in vulvar cancer: Long-term follow-up of the GROningen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS-V) I. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 140, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bakel, B.M.A.; Bakker, E.A.; de Vries, F.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Dutch cardiovascular disease patients. Neth Heart J. 2021, 29, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoofs, M.C.A.; Bakker, E.A.; de Vries, F.; Hartman, Y.A.W.; Spoelder, M.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H.; Buffart, L.M.; Hopman, M.T.E. Impact of Dutch COVID-19 restrictive policy measures on physical activity behavior and identification of correlates of physical activity changes: A cohort study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Electronic Health Records | |||

| Tumor type | Groin involvement (if treatment was surgery) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 94% | None | 16% |

| Melanoma | 5% | Unilateral sentinel node | 21% |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1% | Unilateral lymphadenectomy | 9% |

| Bilateral sentinel node | 40% | ||

| Tumor size | Bilateral lymphadenectomy | 10% | |

| ≤2 cm | 70% | Bilateral sentinel node + lymphadenectomy | 4% |

| >2 cm | 30% | ||

| Tumor location | Self-reported data | ||

| Unilateral > 1 cm | 17% | Age (range: 40–92 years): | |

| Near vulva midline ≤ 1 cm | 65% | <65 | 29 (34.5%) |

| Bilateral (midline involved) | 18% | ≥65 | 55 (65.5%) |

| Tumor stage | Bicycles owned (n = 56) 2: | ||

| I | 74% | City bike | 28 (50.0%) |

| II | 5% | Electrical bike | 26 (46.4%) |

| III | 20% | Mountain bike | 2 (3.6%) |

| Race bike | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Treatment | Other 3 | 4 (7.1%) | |

| Surgery | 83% | ||

| Surgery + adjuvant radiotherapy 1 | 8% | Attempts to reduce bicycling problems (n = 63) 2: | |

| Primary chemo-radiotherapy | 6% | None | 43 (68.3%) |

| Primary radiotherapy | 3% | New bike | 3 (4.8%) |

| New saddle | 14 (22.2%) | ||

| Surgery type (if treatment was surgery) | Bike-fitting/bike adjustments | 4 (6.3%) | |

| Local | 3% | Bicycle clothing | 3 (4.8%) |

| Wide local / re-excision | 96% | Other | 2 (3.2%) |

| With plastic surgery | 1% | ||

| Metric | Baseline Population | Baseline Value | PRO |

|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-5L | |||

| QoL index | Dutch women, all ages [11] | 0.858 ± 0.168 | 0.832 ± 0.224 |

| Mobility problems (any) | Dutch women, 65–69 years [15] | 16.0% | 31.0% |

| Health index (VAS) | Dutch women, 65–69 years [15] | 83.2 ± 11.8 | 75.6 ± 20.0 |

| SQUASH | |||

| Physical activity guideline, total | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 46.5% | 34.2% |

| Physical activity criterion 1: min/week | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 52.4% | 36.7% |

| Physical activity criterion 2: muscle/bone strengthening | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 84.5% | 82.3% |

| Weekly bicycle use | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 64.4% | 48.1% |

| Weekly sport participation | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 40.9% | 30.4% |

| Walking total, min/week | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 367 ± 387 | 240 ± 303 |

| Bicycling total, min/week | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 194 ± 257 | 96 ± 169 |

| Sport participation total, min/week | Dutch women, 65–69 years [6] | 123 ± 261 | 48 ± 129 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van de Berg, N.J.; van Beurden, F.P.; Wendel-Vos, G.C.W.; Duijvestijn, M.; van Beekhuizen, H.J.; Maliepaard, M.; van Doorn, H.C. Patient-Reported Mobility, Physical Activity, and Bicycle Use after Vulvar Carcinoma Surgery. Cancers 2023, 15, 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15082324

van de Berg NJ, van Beurden FP, Wendel-Vos GCW, Duijvestijn M, van Beekhuizen HJ, Maliepaard M, van Doorn HC. Patient-Reported Mobility, Physical Activity, and Bicycle Use after Vulvar Carcinoma Surgery. Cancers. 2023; 15(8):2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15082324

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan de Berg, Nick J., Franciscus P. van Beurden, G. C. Wanda Wendel-Vos, Marjolein Duijvestijn, Heleen J. van Beekhuizen, Marianne Maliepaard, and Helena C. van Doorn. 2023. "Patient-Reported Mobility, Physical Activity, and Bicycle Use after Vulvar Carcinoma Surgery" Cancers 15, no. 8: 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15082324

APA Stylevan de Berg, N. J., van Beurden, F. P., Wendel-Vos, G. C. W., Duijvestijn, M., van Beekhuizen, H. J., Maliepaard, M., & van Doorn, H. C. (2023). Patient-Reported Mobility, Physical Activity, and Bicycle Use after Vulvar Carcinoma Surgery. Cancers, 15(8), 2324. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15082324