Adapting the Voicing My CHOiCES Advance Care Planning Communication Guide for Australian Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Appropriateness, Acceptability, and Considerations for Clinical Practice

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How acceptable is the American VMC guide for Australian AYAs?

- What aspects of the VMC guide are considered stressful, beneficial, and burdensome?

- How appropriate is the VMC guide for the Australian clinical context?

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Research Design

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Research Question 1: How Acceptable Is the American VMC for Australian AYAs?

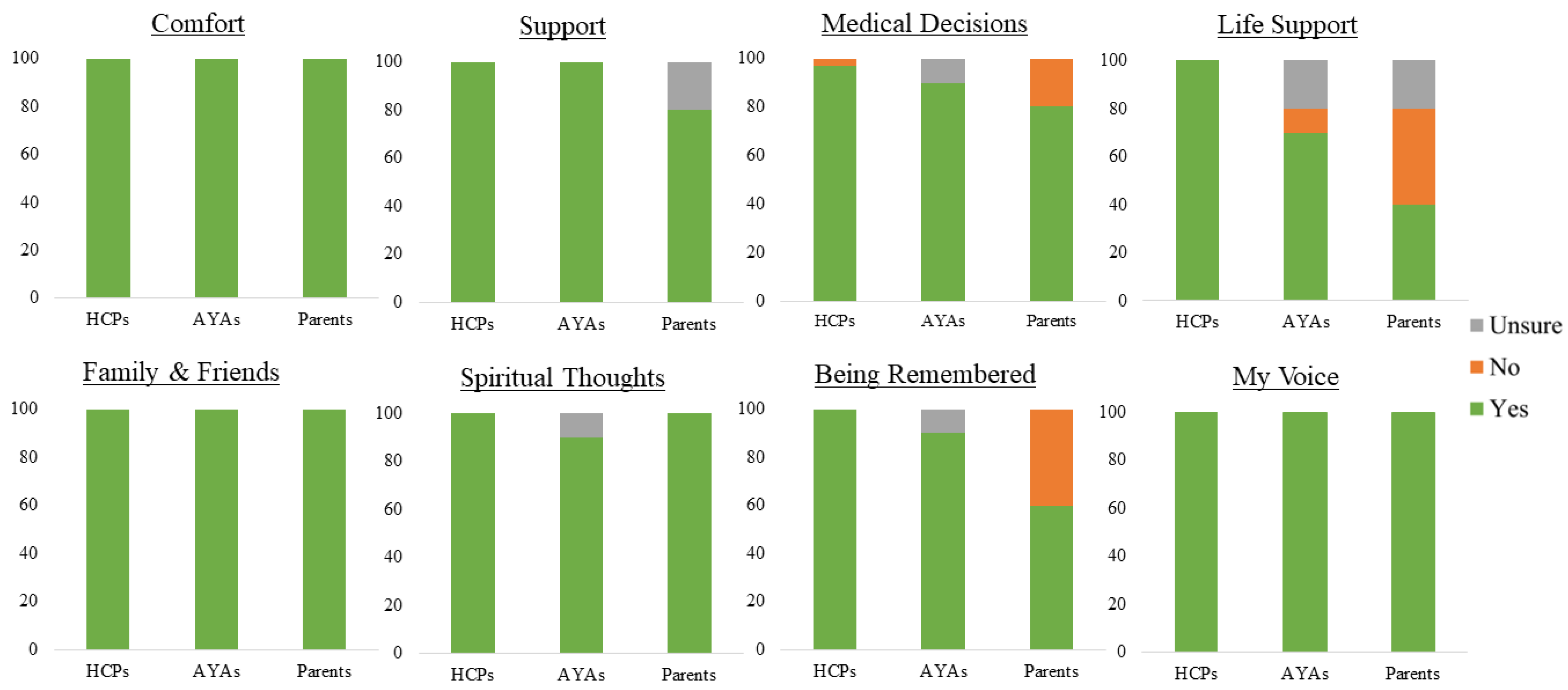

3.2.1. Acceptability: Appropriateness of Content

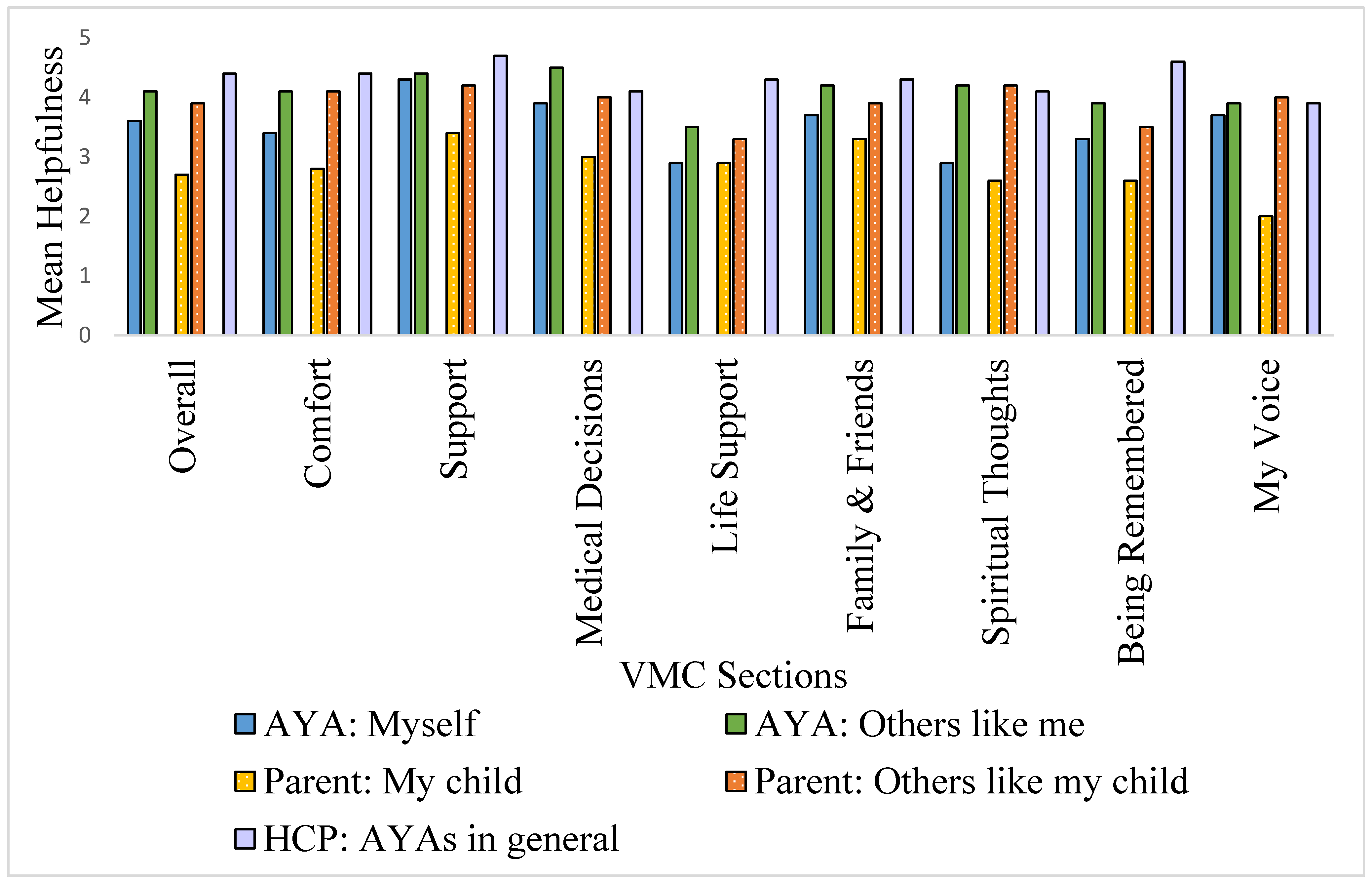

3.2.2. Acceptability: Helpfulness

3.2.3. Acceptability: Perceived Stress

3.3. Research Question 2: What Aspects of the VMC Guide Are Considered Stressful, Beneficial, and Burdensome?

3.3.1. Anticipated Sources of Stress

- (i)

- Individual factors

“I wouldn’t be doing a page like this with someone who did not know their treatment was not curative, … someone who isn’t comfortable to talk about it.”(Female health professional (HCP), 39 years)

“When I was going through treatment, it never once crossed my mind—about a funeral or what’s going to happen to me once I pass away. … If you’re going through treatment [those thoughts] can be quite overwhelming and just quite negative. … I’d rather focus on [the] positive. It sort of doesn’t give you any hope when you’re confronted with questions like that.”(Female AYA, 24 years)

- (ii)

- AYA-related developmental factors

“Then at that age when that’s all you can do, when you’re being asked ‘so when you want to die, where do you want to die.’ It’s like—‘but hang on a minute, I want to go to the movies with my friends’.”(Female bereaved parent, 52 years)

“Probably the last question ‘when the end of my life is near’, … I think no matter how you frame that it’s going to create some stress for the young person.”(Female HCP, 37 years)

“You’re brought up… you go to the doctor, and you do what the doctor tells you. So, to be able to stop previously started treatment, or to ‘hire or fire a healthcare worker’—that’s stuff that’s like, wow—hold on—that’s a bit… [intimidating]”(Female parent, 52 years, referring to the Medical Decisions page)

- (iii)

- Concerns around the potential impact on family and friends

“It also has the scope to make you feel concerned about how your loved ones are going to be feeling after your death, and that can be really upsetting.”(Male HCP, 49 years)

- (iv)

- Interpersonal interactions around the anticipated stress of HCPs using the guide

“I’m sure there’s going to be young people who don’t want their default, their parent or guardian, to be making those decisions.”(Female HCP, 27 years)

“Sometimes because the parents or the siblings can’t get there [to accepting the possibility of death] the child feels… [that] they don’t have permission to get there, and I think that permission to die … and permission to express your feelings before you die is very important.”(Female HCP, 32 years)

As one health professional noted, successful engagement with the guide and a reduction in such distress would be “… dependent on you setting the scene and having that person walking you through it, someone else who can give it [VMC] with [an] explanation rather than just throw it [to them] as a questionnaire.”(Female HCP, 49 years)

3.3.2. Experience of Using the VMC Guide: Benefit and Burden

3.4. Research Question 3: How Appropriate Is the VMC Guide for the Australian Context?

“I think again dragonflies are really—I haven’t been to the (United) States a lot. There are a lot dragonflies around. More than you see here, I don’t know why, and so maybe it’s more—it has a connotation for them but I don’t know about it.”(Female HCP, 46 years)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AYA | Adolescent and young adult |

| VMC | Voicing My CHOiCES |

| US | United States of America |

References

- Aubin, S.; Barr, R.; Rogers, P.; Schacter, B.; Bielack, S.S.; Ferrari, A.; Manchester, R.A.; McMaster, K.; Morgan, S.; Patterson, M.; et al. What Should the Age Range Be for AYA Oncology? J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2011, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, A.G.; Dreyzin, A.; Miller, K.D.; Seynnaeve, B.K.N.; Rapkin, L.B. Adolescent and young adult oncology-past, present, and future. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.L.; Kent, E.E.; Trevino, K.M.; Parsons, H.M.; Zebrack, B.J.; Kirchhoff, A.C. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 2016, 122, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, R.; Zabih, V.; Kurdyak, P.; Sutradhar, R.; Nathan, P.C.; McBride, M.L.; Gupta, S. Psychiatric Disorders in Adolescent and Young Adult-Onset Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Zadeh, S.; Battles, H.; Baird, K.; Ballard, E.; Osherow, J.; Pao, M. Allowing adolescents and young adults to plan their end-of-life care. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; Perez, J.; Cheng, Y.I.; Sill, A.; Wang, J.; Lyon, M.E. Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents’ preferences: Results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arruda-Colli, M.N.F.; Sansom-Daly, U.; Dos Santos, M.A.; Wiener, L. Considerations for the cross-cultural adaptation of an advance care planning guide for youth with cancer. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 6, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom-Daly, U.M.; Wakefield, C.E.; Patterson, P.; Cohn, R.J.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Wiener, L.; Fardell, J.E. End-of-Life Communication Needs for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Recommendations for Research and Practice. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Heinze, K.E.; Kelly, K.P.; Wiener, L.; Casey, R.L.; Bell, C.J.; Wolfe, J.; Garee, A.M.; Watson, A.; Hinds, P.S. Palliative Care as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62 (Suppl. 5), S829–S833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Gurren, L.; McLachlan, S.-A.; Wawryk, O.; Philip, J. Communication about early palliative care: A qualitative study of oncology providers’ perspectives of navigating the artful introduction to the palliative care team. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1003357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudore, R.L.; Lum, H.D.; You, J.J.; Hanson, L.C.; Meier, D.E.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Matlock, D.D.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Korfage, I.J.; Ritchie, C.S.; et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 821–832.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vemuri, S.; Hynson, J.; Williams, K.; Gillam, L. Conceptualising paediatric advance care planning: A qualitative phenomenological study of paediatricians caring for children with life-limiting conditions in Australia. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, M.E.; D’Angelo, L.J.; Dallas, R.H.; Hinds, P.S.; Garvie, P.A.; Wilkins, M.L.; Garcia, A.; Briggs, L.; Flynn, P.M.; Rana, S.R.; et al. A randomized clinical trial of adolescents with HIV/AIDS: Pediatric advance care planning. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, M.E.; Jacobs, S.; Briggs, L.; Cheng, Y.I.; Wang, J. A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: Anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2014, 54, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Wiener, L.; Jacobs, S.; Bell, C.J.; Madrigal, V.; Mooney-Doyle, K.; Lyon, M.E. Weaver et al’s Response to Morrison: Advance Directives/Care Planning: Clear, Simple, and Wrong. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, K.; Grossoehme, D.H.; Friebert, S.; Baker, J.N.; Needle, J.; Lyon, M.E. “Living life as if I never had cancer”: A study of the meaning of living well in adolescents and young adults who have experienced cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, E.; Wolfe, J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebert, S.; Grossoehme, D.H.; Baker, J.N.; Needle, J.; Thompkins, J.D.; Cheng, Y.I.; Wang, J.; Lyon, M.E. Congruence Gaps Between Adolescents With Cancer and Their Families Regarding Values, Goals, and Beliefs About End-of-Life Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e205424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S.; Hughes, R.; Pickstock, S.; Auret, K. Advance Care Planning Discussions with Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients Admitted to a Community Palliative Care Service: A Retrospective Case-Note Audit. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Ballard, E.; Brennan, T.; Battles, H.; Martinez, P.; Pao, M. How I wish to be remembered: The use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, A.; Hasson, F.; Casson, K.; Slater, P.; McIlfatrick, S. Young adults understanding and readiness to engage with palliative care: Extending the reach of palliative care through a public health approach: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, M.E.; McCabe, M.A.; Patel, K.M.; D’Angelo, L.J. What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 35, e521–e526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.E.; Sansom-Daly, U.M.; Bryant, R. Paediatric advance care plans: A cross-sectional survey of healthy young adults. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 12, e654–e655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, S.; Cuvelier, G.; Harlos, M.; Barr, R. Palliative care in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadeh, S.; Pao, M.; Wiener, L. Opening end-of-life discussions: How to introduce Voicing My CHOiCES™, an advance care planning guide for adolescents and young adults. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, C.; Tan, A.; Slaven, M.; Elston, D.; Heyland, D.K.; Howard, M. Exploring patient-reported barriers to advance care planning in family practice. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L.; Bedoya, S.; Battles, H.; Sender, L.; Zabokrtsky, K.; Donovan, K.A.; Thompson, L.M.A.; Lubrano di Ciccone, B.B.; Babilonia, M.B.; Fasciano, K.; et al. Voicing their choices: Advance care planning with adolescents and young adults with cancer and other serious conditions. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 20, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Rosenberg, A.R.; Tager, J.; Wichman, C.S.; Wiener, L. A Summary of Pediatric Palliative Care Team Structure and Services as Reported by Centers Caring for Children with Cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poort, H.; Zupanc, S.N.; Leiter, R.E.; Wright, A.A.; Lindvall, C. Documentation of Palliative and End-of-Life Care Process Measures Among Young Adults Who Died of Cancer: A Natural Language Processing Approach. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2020, 9, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, J.W.; Currie, E.R.; Martello, V.; Gittzus, J.; Isack, A.; Fisher, L.; Lindley, L.C.; Gilbertson-White, S.; Roeland, E.; Bakitas, M. Barriers to Optimal End-of-Life Care for Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer: Bereaved Caregiver Perspectives. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. JNCCN 2021, 19, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.J.; Skiles, J.; Pradhan, K.; Champion, V.L. End-of-life experiences in adolescents dying with cancer. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, L.V. Advance Care Planning With Adolescent and Young Adult Stem Cell Transplant Patients; University of Maryland School of Nursin: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L. Advance care planning communication for young adults: A role for simulated learning. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2017, 19, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmerski, T.M.; Weiner, D.J.; Matisko, J.; Schachner, D.; Lerch, W.; May, C.; Maurer, S.H. Advance care planning in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: A quality improvement project. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2016, 51, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fladeboe, K.M.; O’Donnell, M.B.; Barton, K.S.; Bradford, M.C.; Steineck, A.; Junkins, C.C.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Rosenberg, A.R. A novel combined resilience and advance care planning intervention for adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: A feasibility and acceptability cohort study. Cancer 2021, 127, 4504–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.; Sehring, S.A.; Partridge, J.C.; Cooper, B.A.; Hughes, A.; Philp, J.C.; Amidi-Nouri, A.; Kramer, R.F. Barriers to palliative care for children: Perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, K.D.; List, B.; Brinkman, W.B.; Prutsky Lopez, G.; Asi, N.; Erwin, P.; Wang, Z.; Domecq Garces, J.P.; Montori, V.M.; LeBlanc, A. Shared Decision Making in Pediatrics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad. Pediatr. 2015, 15, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M.; Johnson, R.; Thompson, K.; Anazodo, A.; Albritton, K.; Ferrari, A.; Stark, D. Models of care for adolescent and young adult cancer programs. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.; Mazer, B.; Butow, P.N.; Tattersall, M.H.; Clayton, J.M.; Davidson, P.M.; Young, J.; Ladwig, S.; Epstein, R.M. A question prompt list for patients with advanced cancer in the final year of life: Development and cross-cultural evaluation. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolescent and Young Adults with Cancer: Model of Care for NSW/ACT; Cancer Institute NSW: St Leonards, Australia, 2019.

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Allison, K.R.; Bibby, H.; Thompson, K.; Lewin, J.; Briggs, T.; Walker, R.; Osborn, M.; Plaster, M.; Hayward, A.; et al. The Australian Youth Cancer Service: Developing and Monitoring the Activity of Nationally Coordinated Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Care. Cancers 2021, 13, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluye, P.; Hong, Q.N. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L.; Bedoya, S.Z.; Fry, A.; Pao, M. Voicing My CHOiCES: The revision of an Advance Care Planning guide. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; Bedoya, S.Z.; Battles, H.; Leonard, S.; Fasciano, K.; Heath, C.; Lyon, M.; Donovan, K.; Colli, M.; de Arruda, N.F. Courageous Conversations: Advance Care Planning and Family Communication; Pediatric Blood & Cancer: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. S596–S597. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census QuickStats; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Education and Work, Australia; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Cancer in Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander People of Australia; Australian Institute of Health Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- O’Brien, A.P.; Bloomer, M.J.; McGrath, P.; Clarke, K.; Martin, T.; Lock, M.; Pidcock, T.; van der Riet, P.; O’Connor, M. Considering Aboriginal palliative care models: The challenges for mainstream services. Rural. Remote Health 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, J.; Lehto, R.; Wyatt, G. Spirituality, Quality of Life, and End of Life Among Indigenous Peoples: A Scoping Review. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2021, 32, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, S.; Phelan, C. Health-care workers’ understanding of and barriers to palliative care services to Aboriginal children with cancer. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Allison, K.; Perz, J.; Power, R.; The Out with Cancer Study Team. LGBTQI cancer patients’ quality of life and distress: A comparison by gender, sexuality, age, cancer type and geographical remoteness. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 873642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, L.; McConnell, D.G.; Latella, L.; Ludi, E. Cultural and religious considerations in pediatric palliative care. Palliat. Support. Care 2013, 11, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, S.Z.; Fry, A.; Gordon, M.L.; Lyon, M.E.; Thompkins, J.; Fasciano, K.; Malinowski, P.; Heath, C.; Sender, L.; Zabokrtsky, K.; et al. Adolescent and Young Adult Initiated Discussions of Advance Care Planning: Family Member, Friend and Health Care Provider Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 871042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moré, J.M.; Lang-Brown, S.; Romo, R.D.; Lee, S.J.; Sudore, R.; Smith, A.K. “Planting the Seed”: Perceived Benefits of and Strategies for Discussing Long-Term Prognosis with Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 2367–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Section Title | Abbreviated Title | Section Description/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORIGINAL SECTIONS | |||

| A | Introduction | Not applicable | Provides a brief overview of the guide while offering comfort and purpose to AYAs who may have mixed feelings about utilising a guide, informs AYAs that document completion is based on their thoughts and desires, and illustrates autonomy and respect for their ability to make decisions about their own care. |

| 1 | How I Want to be Comforted | Comfort | A place to describe how the AYA wants to be cared for and what will make them feel more comfortable (music, movies, food, atmosphere) in addition to preferences surrounding pain management. |

| 2 | How I Would Like to be Supported So I Don’t Feel Alone | Support | Allows the individual to describe who and when visitors are wanted, as well as designating how information on health status should be shared with others. |

| 3 | Who I Want to Make My Medical Care Decisions if I Cannot Make Them on My Own | Medical Decisions | Designating a durable power of attorney and expressing preferences for types of care decisions. |

| 4 | The Types of Life Support Treatment I Want, or Do Not Want | Life Support | A space for the individual to express their desire for/against life support treatments and to specify any terms on its usage, as well as to indicate where they would like to be at the end of their life. |

| 5 | What I Would Like My Family and Friends to Know About Me | Family and Friends | A space for the individual to express gratitude or regret towards family and friends. |

| 6 | My Spiritual Thoughts and Wishes | Spiritual Thoughts | A place to write down their thoughts on spiritual topics or sources of meaning, and to discuss their preferences. |

| 7 | How I Wish to be Remembered | Being Remembered | A space for the individual to designate burial and funeral preferences as well as provide information on organ donation and autopsy. This section also allows the individual to designate who important belongings should be distributed to and how they would like to be remembered on special occasions. |

| 8 | My Voice | My Voice | A space to write letters to loved ones. |

| B | Glossary | Not applicable | Provides definitions of terms used throughout the guide. |

| PROPOSED NEW SECTIONS | |||

| 9 | Online Accounts | Online Accounts | Provides a place for AYAs to gather account information for use by friends and family, and indicate preferences around what they would prefer to happen with their social media accounts, in the event of the patient’s death. |

| 10 | VMC Storage | Storage | A page that allows AYAs to specify where they would like their copy of VMC to be kept and who should have access to it, per section as relevant. |

| (a) | |||||

| AYAs (n = 10) | Health Professionals (n = 28) | Parents (n = 5) | Total (n = 43) | ||

| Age | Mean (SD) | 22.40 (3.2) | 41.9 (9.6) | 50.80 (3.9) | 38.4 (12.3) |

| Range | 16–26 1 | 25–61 | 46–56 | 16–61 | |

| Gender (n (%)) | Male | 4 (40) | 5 (18) | 1 (20) | 10 (23) |

| Female | 6 (60) | 23 (82) | 4 (80) | 33 (77) | |

| Country of birth (n (%)) | Australia | 8 (80) | 19 (68) | 4 (80) | 31 (72) |

| United Kingdom | 0 | 5 (18) | 0 | 5 (12) | |

| New Zealand | 1 (10) | 1 (4) | 0 | 2 (5) | |

| Other 2 | 1 (10) | 3 (11) | 1 (20) | 5 (12) | |

| (b) | |||||

| AYAs | |||||

| Highest education completed 1 n (%) | Year 10 or below | 1 (10) | |||

| Year 12 | 2 (20) | ||||

| TAFE certificate or diploma, college | 1 (10) | ||||

| University degree | 5 (50) | ||||

| Post-graduate degree | 1 (10) | ||||

| Current employment 2 | Employed | 8 (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 1 (%) | ||||

| Language other than English spoken at home—n (%) | Yes | 3 (30) 3 | |||

| No | 7 (70) | ||||

| Age at cancer diagnosis | Mean (SD) | 17.10 (2.5) | |||

| Range | 15–23 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | Mean (SD) | 5.30 (2.7) | |||

| Range | 1–10 | ||||

| Cancer type 4 n (%) | Blood | 5 (50) | |||

| Solid | 4 (40) | ||||

| Brain | 1 (10) | ||||

| Current cancer stage 5 n (%) | 1 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 1 (14) | ||||

| 3 | 1 (14) | ||||

| 3–4 | 1 (14) | ||||

| 4 | 2 (29) | ||||

| N/A | 2 (29) | ||||

| Risk Level 6 n (%) | Low | 1 (10) | |||

| Intermediate | 3 (33.3) | ||||

| High | 1 (10) | ||||

| Unsure | 3 (33.3) | ||||

| Treatments received n (%) | Surgical removal of cancer | 5 (50) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 8 (80) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 5 (50) | ||||

| Bone marrow/stem cell transplant | 4 (40) | ||||

| (c) | |||||

| Parents | |||||

| Highest education completed 1 n (%) | Year 10 or below | 0 | |||

| Year 12 | 0 | ||||

| TAFE certificate or diploma, college | 3 (60) | ||||

| University degree | 2 (40) | ||||

| Post-graduate degree | 0 | ||||

| Current employment 2 | Employed | 1 (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 2 (%) | ||||

| Language other than English spoken at home—n (%) | Yes | 0 | |||

| No | 5 (100) | ||||

| Current age of child 3 | Mean (SD) | 19.33 (2.9) | |||

| Range | 16–21 | ||||

| Age of child when they died 4 | Mean (SD) | 17 (2.8) | |||

| Range | 15–19 | ||||

| Child age at cancer diagnosis | Mean (SD) | 15.80 (3.3) | |||

| Range | 12–21 | ||||

| Child’s cancer type 5 n (%) | Blood | 2 (40) | |||

| Solid | 1 (20) | ||||

| Brain | 2 (40) | ||||

| Child’s cancer stage 6 n (%) | 1 | 2 (67) | |||

| 2 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 0 | ||||

| 3–4 | 0 | ||||

| 4 | 1 (33) | ||||

| N/A | 0 | ||||

| Child’s cancer risk level 7 n (%) | Low | 1 (%) | |||

| Intermediate | 0 (%) | ||||

| High | 3 (%) | ||||

| Unsure | 0 (%) | ||||

| Treatments received n (%) | Surgical removal of cancer | 2 (40) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 5 (100) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | 4 (80) | ||||

| Bone marrow/stem cell transplant | 1 (20) | ||||

| Years of Experience | Mean (SD) | 16.9 (7.8) |

| Range | 4–30 | |

| Healthcare profession—n (%) | Oncologist or Haematologist | 8 (29) |

| Nursing | 11 (39) | |

| Clinical Psychologist | 3 (11) | |

| Dietitian | 1 (4) | |

| Social Worker | 6 (21) | |

| Leisure Therapist | 1 (4) | |

| Specialty within oncology—n (%) | Paediatrics | 15 (54) |

| AYAs | 4 (14) | |

| Adult | 8 (29) | |

| Unspecified/missing | 1 (4) | |

| Estimated number of AYAs treated who have died from cancer—n (%) | <5 | 2 (7) |

| 5–10 | 3 (11) | |

| 10–15 | 5 (18) | |

| 15+ | 18 (64) |

| Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Intrapersonal: Individual Differences | |

| Patient’s health | “If it’s asked … (of) someone who’s got poorer prognosis then all of a sudden, to me, I would then be thinking this is the end, or this is when they’re really sick.” (Comfort, Female, 38, Healthcare professional [HCP]) |

| Prognostic awareness | “It depends what experience they’ve been through. You know, if they’re a leukaemic who’s been through a huge amount of treatment, then they have a transplant and they’re failing, I think they can deal with it better than we think.” (Life Support, Male, 60, HCP) |

| Higher distress, avoidant coping | “In that beginning phase, you hold on to every little bit (of hope). You are so devastated by that ‘C’ diagnosis. …To think about it in advance and put it into her mind that she might need life support somewhere along the way, I wouldn’t even dream of it.” (Life Support, Female, 46, Parent) |

| Desire to plan | “Years ago, this little girl … she had lost her mum and she was dying, and she knew. She got an exercise book—she was 13—and she started writing stuff down. … This would have been perfectly right for her, but I think it would be very confronting for other people.” (Being Remembered, Female, 39, HCP) |

| Spiritual beliefs | “I looked around and I saw babies who were screaming. It was so horrible, I thought to myself there’s no way that there’s a God that would do this to people. Something like this (Spiritual section) while I was in my treatment … would have irritated me, because I would have been like, I don’t believe in this. I don’t think that it’s important at all. I just don’t want to be associated with it, and I just don’t want to do anything with it.” (Spiritual Thoughts, Female, 24, Adolescent/young adult [AYA]) |

| Intrapersonal: common AYA developmental factors | |

| Decision-making stress | “These questions are good in that they are quite clear that (these are) moments when there is really not any hope … but I think any time that you’re thinking about life support there is that question of, “but what if I recover?” Like just being unable to predict.” (Life Support, Female, 27, HCP) |

| “The ones who are like on that 17/18 (year-old) border I’ve just kind of seen them default to their parents because that’s what they’ve been doing so much of their lives.” (Medical Decisions, Female, 27, HCP) | |

| “This young man I worked with recently, he really struggled to find the words and put a lot of pressure on himself because he’s like, ‘mum’s going to read this over and over and over again. I don’t want to stuff it up’”. (My Voice, Female, 34, HCP) | |

| Complex concepts | “Young people don’t plan their funeral and you’d never think you’d have to plan your funeral… As a young person, that’s not even in your mind, it’s not even a thought. So, to sit down and (ask), you know, “do you want an open casket, do you want a closed casket?”—I guess that, again, just drives home that something can go wrong.” (Being Remembered, Male, 23, AYA) |

| “’If I can’t go to the bathroom’, … probably by their nature, young people haven’t had much exposure to that kind of stuff. Whereas for adults, if they have been caring for someone who’s deteriorating, they know what happens. … (It) might actually be quite distressing because they wouldn’t have pictured themselves in that space.” (Comfort, Female, 35, HCP) | |

| “Some of the questions—(about having) a limited autopsy, a standard autopsy, a research protocol autopsy—what would a young person know, feel, about an autopsy? And then actually there are four different autopsy choices there, as well as being an organ donor and donating my body to science.” (Being remembered, Male, 48, HCP) | |

| “If you’re told, ‘you’ve got this (disease), and we believe you’ve got 12 months to live’, or ‘Look, we believe that the treatment we’re going to give you (will) give you a really good chance of survival’—if you’ve been told that and then you’re given this (guide) … you might actually start to think it’s worse than what it is. ‘They’re not telling me the truth. I am going to die.’” (S2, Female, 52, Parent) | |

| “I wouldn’t want to think about the specifics. I mean, it doesn’t matter. I’m gone.” (Online Presence Management, Female, 20, AYA, 20) | |

| Interpersonal: Internal social perceptions: how AYAs think about their world | |

| Social pressure | “Not necessarily intentional pressure, but I could see the young person having certain ideas and then feeling pressure that that (decision is) not what the parents or family might want.” (Support, Female, 27, HCP) |

| Impact on others | “The only thing I’m frightened by is in this section is probably the impact on the person that would be making those decisions for you (how they may cope).” (Medical Decisions, Male, 26, AYA) |

| Stress from the reflective process | “This young man … he wanted to apologise to his brother, and it was very stressful for him to find the right words. So, we (wrote letters) … together and bounced ideas around, but it brought up a lot of, I guess, regrets for him.” (Friends and Family, Female, 34, HCP) |

| “If they’re trying to answer questions where they don’t have a support network … it’s like a sort of, a mirror back in your face letting you know that you don’t really have people to write down, so that can be upsetting.” (Support, Female, 24, AYA) | |

| Interpersonal: External social processes and how AYAs interact with their social connections | |

| Conflicting opinions between patient and family | “Most (AYAs) can be really, really realistic about what their wishes are. It can be very stressful because maybe their parents are pushing for their treatment or pushing for any measures that can continue their life as long as possible. … I’ve had a patient where he was very up front to ask about what he wanted but then was continuing (treatment) for his parents.” (Life Support, Female, 25, HCP) |

| “If someone comes from quite a religious or spiritual family, they may now be feeling that they want to voice something that may be different from their family (and) that could create some stress. … Their parents may say, “Oh no, we want the chaplain to come every day”, but the young person will actually (think), “No, I don’t want any of that”.” (Spiritual thoughts, Female, 37, HCP) | |

| How guide is introduced | “If they were slowly eased into it with someone like a clinical psychologist (it would be better) … ‘Have your treatment and then if you want, we can do it now, or you can have a think about it and when you’re ready just tell me’. It’s [about] control again. ‘This is when I want to broach it; not when you want.’” (Being Remembered, Male, 56, Parent) |

| Source of Stress | Clinical Implications for Health Professionals |

|---|---|

| Intrapersonal: Individual Differences | |

| Patient’s health | Lead AYAs (and their family members) into conversations about VMC early in the treatment trajectory by introducing broad concepts gently, and repeatedly checking the AYAs are comfortable proceeding with the conversation/getting their permission |

| Prognostic awareness | Check in with patients at the start of each conversation by asking (again) what the patient’s current understanding of their illness, treatment plan, and next steps is. This can include health professionals asking what patients recall of previous conversations, what they have continued to think about, and what else (worries, memories, prior experiences) may be playing on their minds with regard to their current health situation |

| Higher distress, avoidant coping | Regularly monitor and assess patients’ current physical- and symptom-related burden to enable early interventions and additional supportive care as needed. Conversations around palliative care topics including VMC could be framed as ways to understand their symptom/supportive care needs to enhance their current quality of life. |

| Screen for and assess psychological distress among all AYA patients, including those with additional vulnerabilities due to the timepoint of their treatment trajectory (e.g., newly diagnosed, recently relapsed, other recent treatment setbacks). These times of additional distress can also be used as openings to raise The benefit of having conversations to understand AYAs’ perspectives on their care and quality of life, and also a time to set up an expectation of an honest dialogue with the health professional, including if and when difficult topics become relevant in the future | |

| Spiritual beliefs | Open discussion about religion and what it means to the AYA before introducing the VMC spirituality page can provide them with context. Link with Indigenous health workers if appropriate. |

| Intrapersonal: Common AYA developmental factors | |

| Decision-making stress | Emphasise that the guide is meant to be a ‘living document’ that can change if and as the AYAs’ preferences and circumstances change. Suggest the AYA can start by filling it in with a pencil if this is an issue. |

| Support AYAs to use blank pages at the back of VMC to jot down thoughts/ideas for topics they want further information, support, or discussion about. | |

| Assure AYA that they do not have to make immediate decisions about these things and that they can reach out to others to discuss and help with decision making. | |

| Complex concepts | Explore with AYAs how much information they like to receive, and how they best process and understand information, as early as possible in the treatment trajectory (e.g., visual vs. verbal information delivery). Normalise the fact that these preferences for information and detail can and do change as their clinical situation and physical and emotional circumstances change, and repeatedly check in to clarify if their preferences for information and its discussion/delivery may have changed. |

| Consider also using the ‘teachback’ or ask-tell-ask technique to check AYA’s current understanding, discuss new information, and clarify AYAs’ understandings of what has just been discussed. Engage multidisciplinary team in helping AYAs understand concepts within the guide, normalising their questions by using language such as “What doesn’t make sense?”, “What questions do you have?”, and “What could I/we explain better or differently?”. If appropriate in the context of the clinical relationship, consider asking the AYA to role-play with you and show how they might explain a particular concept/page to a close family/friend; e.g., “How would you explain what we just talked about to your sister/best friend?” | |

| Interpersonal: Internal social perceptions: how AYAs think about their world | |

| Social pressure and impact on others | Normalise and provide psychosocial support around the fact that AYAs can feel very worried about making the ‘right’ decisions and/or causing stress, sadness, or conflict amongst family and friends. Discuss this proactively with AYAs in the context of psychosocial assessments as early as possible, and support AYAs with coping frameworks to balance considering (and prioritising) their own needs versus being concerned with others’ needs and expectations. Support AYAs to explore which key relationships in their lives they would like to involve in decision making and engage psychosocial team members in supporting AYAs with coping strategies to manage stress around any challenging relationships, and with communication strategies to broach trickier issues. |

| Stress from the reflective process | Screen and assess for psychological distress at key transition points of the cancer treatment trajectory (e.g., at the start of a transplant, upon receipt of new clinical information regarding the progression of the disease, or when discussing new treatment options). Normalise that different topics contained within the guide might lead the AYA to feel distressed, worried, or concerned, and highlight the benefits that can come through their discussion by enabling the AYA’s priorities to be supported and enabling the clarification of some certainty amidst the uncertainty. Normalise the range of psychological responses that can arise at different points on the cancer treatment trajectory and offer access to psychological support, regardless of whether AYAs have declined this in the past while recognising that distress levels and desire for help can fluctuate over time. |

| Interpersonal: External social processes and how AYAs interact with their social connections | |

| Conflicting opinions between patient and family | Meet with AYA and family, together and separately if and as appropriate, early in the treatment trajectory and throughout treatment. Name and normalise the fact that AYAs and family members frequently feel differently about aspects of cancer treatment and related decisions (can refer to research evidence regarding a discrepancy in AYA-parent perspectives if this is a clinically useful approach). Flag as early as possible the HCP’s role in terms of being open and honest with the patient and family, and that the HCP will not collude in ‘hiding’ or keeping secrets from AYAs. Use language such as ‘I wonder…’ to explore patient and family concerns about different options and future scenarios and language such as ‘I worry…’ to highlight potential risks to the patient’s wellbeing or care, for instance, certain topics not discussed or care options not considered. |

| How the guide is introduced | Identify which HCP on the multidisciplinary team has the strongest working relationship with the AYA to introduce the guide. Where relevant/appropriate, invite the AYA to take the lead on deciding which sections they may wish to complete with which HCPs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sansom-Daly, U.M.; Zhang, M.; Evans, H.E.; McLoone, J.; Wiener, L.; Cohn, R.J.; Anazodo, A.; Patterson, P.; Wakefield, C.E. Adapting the Voicing My CHOiCES Advance Care Planning Communication Guide for Australian Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Appropriateness, Acceptability, and Considerations for Clinical Practice. Cancers 2023, 15, 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072129

Sansom-Daly UM, Zhang M, Evans HE, McLoone J, Wiener L, Cohn RJ, Anazodo A, Patterson P, Wakefield CE. Adapting the Voicing My CHOiCES Advance Care Planning Communication Guide for Australian Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Appropriateness, Acceptability, and Considerations for Clinical Practice. Cancers. 2023; 15(7):2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSansom-Daly, Ursula M., Megan Zhang, Holly E. Evans, Jordana McLoone, Lori Wiener, Richard J. Cohn, Antoinette Anazodo, Pandora Patterson, and Claire E. Wakefield. 2023. "Adapting the Voicing My CHOiCES Advance Care Planning Communication Guide for Australian Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Appropriateness, Acceptability, and Considerations for Clinical Practice" Cancers 15, no. 7: 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072129

APA StyleSansom-Daly, U. M., Zhang, M., Evans, H. E., McLoone, J., Wiener, L., Cohn, R. J., Anazodo, A., Patterson, P., & Wakefield, C. E. (2023). Adapting the Voicing My CHOiCES Advance Care Planning Communication Guide for Australian Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Appropriateness, Acceptability, and Considerations for Clinical Practice. Cancers, 15(7), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072129