Trial Design for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Methodological Toolkit

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Considerations

2.1. Mechanistic Aspects of Immunotherapy

2.2. Response Assessment with Immunotherapy

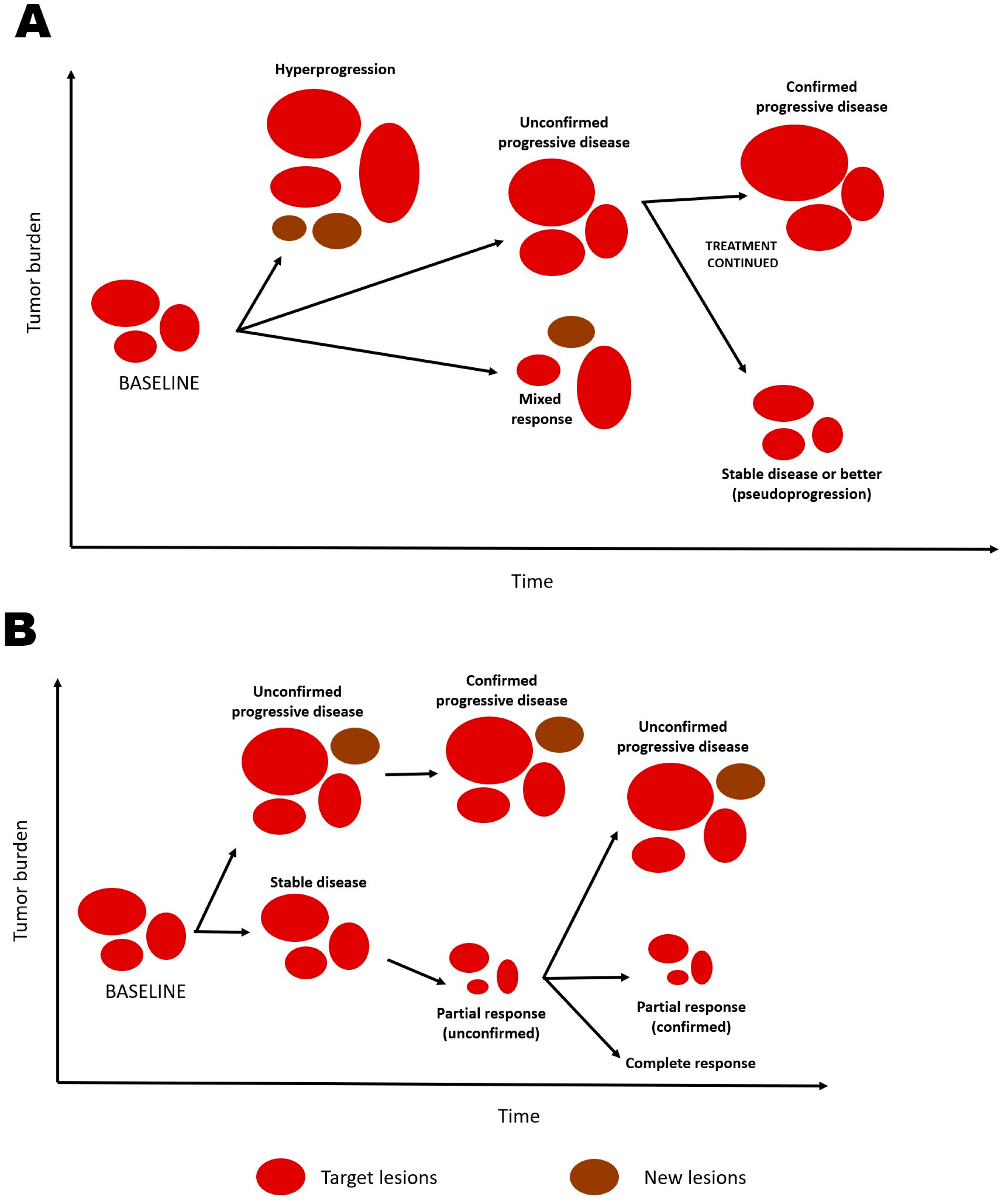

2.2.1. Unique Patterns of Response and Progression

2.2.2. Response Criteria for Immunotherapy

2.2.3. Duration of Response as an Endpoint

2.3. Unique Patterns of Survival Distribution

2.4. Prognostic, Predictive, and Response Biomarkers

2.5. Surrogacy Issues

3. Some Key Decisions in Trial Design

3.1. Early Phase Trials

3.1.1. Single-Arm vs. Randomized Trials

3.1.2. Defining Eligibility

3.1.3. Dose-Escalation Schemes

3.1.4. Safety Assessment

3.1.5. Efficacy Assessment

3.2. Late-Phase Trials

3.2.1. Conventional vs. Adaptive Trials

3.2.2. Choice of Primary Endpoint

3.2.3. Assessment of the Treatment Effect

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoos, A. Development of immuno-oncology drugs—From CTLA4 to PD1 to the next generations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.; Karapetyan, L.; Kirkwood, J.M. Immunotherapy in Melanoma: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Remon, J.; Hellmann, M.D. First-Line Immunotherapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, R.K.; Banchereau, J.; Ribas, A.; Tarhini, A.A.; Weber, J.S.; Fox, B.A.; Drake, C.G. Assessing oncologic benefit in clinical trials of immunotherapy agents. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 1944–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.T. Statistical issues and challenges in immuno-oncology. J. Immunother. Cancer 2013, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mick, R.; Chen, T.T. Statistical Challenges in the Design of Late-Stage Cancer Immunotherapy Studies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postel-Vinay, S.; Aspeslagh, S.; Lanoy, E.; Robert, C.; Soria, J.-C.; Marabelle, A. Challenges of phase 1 clinical trials evaluating immune checkpoint-targeted antibodies. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menis, J.; Litiere, S.; Tryfonidis, K.; Golfinopoulos, V. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer perspective on designing clinical trials with immune therapeutics. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostou, V.; Yarchoan, M.; Hansen, A.R.; Wang, H.; Verde, F.; Sharon, E.; Collyar, D.; Chow, L.Q.; Forde, P.M. Immuno-oncology Trial Endpoints: Capturing Clinically Meaningful Activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4959–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B. Some statistical considerations in the clinical development of cancer immunotherapies. Pharm. Stat. 2018, 17, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C.F.; Panageas, K.S.; Wolchok, J.D. Special considerations in immunotherapy trials. In Oncology Clinical Trials, 2nd ed.; Kelly, W.K., Halabi, S., Eds.; Demos Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Borcoman, E.; Kanjanapan, Y.; Champiat, S.; Kato, S.; Servois, V.; Kurzrock, R.; Goel, S.; Bedard, P.; Le Tourneau, C. Novel patterns of response under immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoragiewicz, M.; Adjei, A.A.; Calvo, E.; Tabernero, J.; Marabelle, A.; Massard, C.; Tang, J.; de Vries, E.G.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Seymour, L. Design and Conduct of Early Clinical Studies of Immunotherapy: Recommendations from the Task Force on Methodology for the Development of Innovative Cancer Therapies 2019 (MDICT). Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2461–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, G.M.; Pazdur, R. Response Rate as an Approval End Point in Oncology: Back to the Future. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, O.J. Immuno-oncology: Understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl. S8), viii6–viii9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogdill, A.P.; Andrews, M.C.; Wargo, J.A. Hallmarks of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, D.; Gubin, M.M.; Schreiber, R.D.; Smyth, M.J. New insights into cancer immunoediting and its three component phases--elimination, equilibrium and escape. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 27, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daud, A.I.; Loo, K.; Pauli, M.L.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Sandoval, P.M.; Taravati, K.; Tsai, K.; Nosrati, A.; Nardo, L.; Alvarado, M.D.; et al. Tumor immune profiling predicts response to anti-PD-1 therapy in human melanoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3447–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, J.; Murphy, C.; Atkins, M.B.; Brahmer, J.R.; Champiat, S.; Feltquate, D.; Krug, L.M.; Moslehi, J.; Pietanza, M.C.; Riemer, J.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) consensus definitions for immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated immune-related adverse events (irAEs) terminology. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, G.; Gasper, H.; Man, J.; Lord, S.; Marschner, I.; Friedlander, M.; Lee, C.K. Defining the Most Appropriate Primary End Point in Phase 2 Trials of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Advanced Solid Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulkey, F.; Theoret, M.R.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R.; Sridhara, R. Comparison of iRECIST versus RECIST V.1.1 in patients treated with an anti-PD-1 or PD-L1 antibody: Pooled FDA analysis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazdait, M.; Mezquita, L.; Lahmar, J.; Ferrara, R.; Bidault, F.; Ammari, S.; Balleyguier, C.; Planchard, D.; Gazzah, A.; Soria, J.; et al. Patterns of responses in metastatic NSCLC during PD-1 or PDL-1 inhibitor therapy: Comparison of RECIST 1.1, irRECIST and iRECIST criteria. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 88, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Hoos, A.; O’Day, S.; Weber, J.S.; Hamid, O.; Lebbé, C.; Maio, M.; Binder, M.; Bohnsack, O.; Nichol, G.; et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: Immune-related response criteria. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 7412–7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, V.L.; Burotto, M. Pseudoprogression and Immune-Related Response in Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3541–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoos, A.; Eggermont, A.M.M.; Janetzki, S.; Hodi, F.S.; Ibrahim, R.; Anderson, A.; Humphrey, R.; Blumenstein, B.; Old, L.; Wolchok, J. Improved endpoints for cancer immunotherapy trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Hwu, W.-J.; Kefford, R.; Weber, J.S.; Daud, A.; Hamid, O.; Patnaik, A.; Ribas, A.; Robert, C.; Gangadhar, T.C.; et al. Evaluation of Immune-Related Response Criteria and RECIST v1.1 in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated With Pembrolizumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Ballinger, M.; Lyons, B.; Soria, J.-C.; Nishino, M.; Tabernero, J.; Powles, T.; Smith, D.; Hoos, A.; McKenna, C.; et al. Immune-Modified Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (imRECIST): Refining Guidelines to Assess the Clinical Benefit of Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champiat, S.; Dercle, L.; Ammari, S.; Massard, C.; Hollebecque, A.; Postel-Vinay, S.; Chaput, N.; Eggermont, A.; Marabelle, A.; Charles Soria, J.; et al. Hyperprogressive Disease Is a New Pattern of Progression in Cancer Patients Treated by Anti-PD-1/PD-L1. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanapan, Y.; Day, D.; Wang, L.; Al-Sawaihey, H.; Abbas, E.; Namini, A.; Siu, L.L.; Hansen, A.; Razak, A.A.; Spreafico, A.; et al. Hyperprogressive disease in early-phase immunotherapy trials: Clinical predictors and association with immune-related toxicities. Cancer 2019, 125, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R.; Mezquita, L.; Texier, M.; Lahmar, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Tessonnier, L.; Mazieres, J.; Zalcman, G.; Brosseau, S.; Le Moulec, S.; et al. Hyperprogressive Disease in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors or With Single-Agent Chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saada-Bouzid, E.; Defaucheux, C.; Karabajakian, A.; Coloma, V.P.; Servois, V.; Paoletti, X.; Even, C.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Loirat, D.; et al. Hyperprogression during anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Reporting Results of Cancer Treatment; World Health Organization Offset Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 1979.

- Nishino, M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Gargano, M.; Suda, M.; Ramaiya, N.H.; Hodi, F.S. Developing a common language for tumor response to immunotherapy: Immune-related response criteria using unidimensional measurements. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3936–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, L.; Bogaerts, J.; Perrone, A.; Ford, R.; Schwartz, L.H.; Mandrekar, S.; Lin, N.U.; Litière, S.; Dancey, J.; Chen, A.; et al. iRECIST: Guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e143–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, J.A.; Howie, L.J.; Pelosof, L.; Kim, T.; Liu, J.; Goldberg, K.B.; Sridhara, R.; Blumenthal, G.M.; Farrell, A.T.; Keegan, P.; et al. A 25-Year Experience of US Food and Drug Administration Accelerated Approval of Malignant Hematology and Oncology Drugs and Biologics: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andtbacka, R.H.; Kaufman, H.L.; Collichio, F.; Amatruda, T.; Senzer, N.; Chesney, J.; Delman, K.A.; Spitler, L.E.; Puzanov, I.; Agarwala, S.S.; et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, P.; Phan, G.Q.; Maker, A.V.; Robinson, M.R.; Quezado, M.M.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Kammula, U.S.; Royal, R.E.; et al. Autoimmunity correlates with tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6043–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Aplenc, R.; Barrett, D.M.; Bunin, N.J.; Chew, A.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Zheng, Z.; Lacey, S.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Weiner, G.J.; Pardoll, D.M. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4828–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettinger, S.; Horn, L.; Jackman, D.; Spigel, D.; Antonia, S.; Hellmann, M.; Powderly, J.; Heist, R.; Sequist, L.V.; Smith, D.C.; et al. Five-Year Follow-Up of Nivolumab in Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results From the CA209-003 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, M.; Grob, J.-J.; Aamdal, S.; Bondarenko, I.; Robert, C.; Thomas, L.; Garbe, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Testori, A.; Chen, T.-T.; et al. Five-year survival rates for treatment-naive patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in a phase III trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Sznol, M.; McDermott, D.F.; Kluger, H.M.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sharfman, W.H.; Brahmer, J.R.; Lawrence, D.P.; Atkins, M.B.; Powderly, J.D.; et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Kluger, H.; Callahan, M.K.; Postow, M.A.; Rizvi, N.A.; Lesokhin, A.M.; Segal, N.H.; Ariyan, C.E.; Gordon, R.-A.; Reed, K.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Hamid, O.; Daud, A.; Wolchok, J.D.; Joshua, A.M.; Hwu, W.-J.; Weber, J.S.; Gangadhar, T.C.; Joseph, R.W.; et al. Durable Complete Response After Discontinuation of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Metastatic Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1668–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; Levit, L.A.; Schilsky, R.L.; Averbuch, S.D.; Chen, D.; Kirkwood, J.M.; McShane, L.M.; Sharon, E.; Mileham, K.F.; Postow, M.A. Trial Reporting in Immuno-Oncology (TRIO): An American Society of Clinical Oncology-Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Statement. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Thomas, L.; Bondarenko, I.; O’Day, S.; Weber, J.; Garbe, C.; Lebbe, C.; Baurain, J.-F.; Testori, A.; Grob, J.-J.; et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2517–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Long, G.V.; Brady, B.; Dutriaux, C.; Maio, M.; Mortier, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Rutkowski, P.; McNeil, C.; Kalinka-Warzocha, E.; et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G., Jr.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittmeyer, A.; Barlesi, F.; Waterkamp, D.; Park, K.; Ciardiello, F.; von Pawel, J.; Gadgeel, S.M.; Hida, T.; Kowalski, D.M.; Dols, M.C.; et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantoff, P.W.; Higano, C.S.; Shore, N.D.; Berger, E.R.; Small, E.J.; Penson, D.F.; Redfern, C.H.; Ferrari, A.C.; Dreicer, R.; Sims, R.B.; et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Procopio, G.; Plimack, E.R.; et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, T.S.; Wu, Y.-L.; Thongprasert, S.; Yang, C.-H.; Chu, D.-T.; Saijo, N.; Sunpaweravong, P.; Han, B.; Margono, B.; Ichinose, Y.; et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, E.L.; Freidlin, B. Interim Futility Monitoring Assessing Immune Therapies With a Potentially Delayed Treatment Effect. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2444–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.T. Milestone Survival: A Potential Intermediate Endpoint for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, djv156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péron, J.; Lambert, A.; Munier, S.; Ozenne, B.; Giai, J.; Roy, P.; Dalle, S.; Machingura, A.; Maucort-Boulch, D.; Buyse, M. Assessing long-term survival benefits of immune checkpoint inhibitors using the net survival benefit. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 1186–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, K.; Uno, H.; Kim, D.H.; Tian, L.; Kane, R.C.; Takeuchi, M.; Fu, H.; Claggett, B.; Wei, L.-J. Interpretability of Cancer Clinical Trial Results Using Restricted Mean Survival Time as an Alternative to the Hazard Ratio. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1692–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Li, W. Treatment effects measured by restricted mean survival time in trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.D.; Zalcberg, J.R.; Peron, J.; Coart, E.; Burzykowski, T.; Buyse, M. Understanding and Communicating Measures of Treatment Effect on Survival: Can We Do Better? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.M.; Fell, G.; Ventz, S.; Arfé, A.; Vanderbeek, A.M.; Trippa, L.; Alexander, B.M. Deviation from the Proportional Hazards Assumption in Randomized Phase 3 Clinical Trials in Oncology: Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6339–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration/National Institutes of Health. FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group. In BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and Other Tools) Resource; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ballman, K.V. Biomarker: Predictive or Prognostic? J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3968–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, R.; Zhou, D.; Lord, S.J.; Marschner, I.; Cooper, W.A.; Lewis, C.R.; John, T.; Yang, J.C.-H.; Lee, C.K. PD-L1 expression as a prognostic marker in patients treated with chemotherapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, R.S.; Baas, P.; Kim, D.-W.; Felip, E.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.-Y.; Molina, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Arvis, C.D.; Ahn, M.-J.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.; Reckamp, K.L.; Baas, P.; Crinò, L.; Eberhardt, W.E.E.; Poddubskaya, E.; Antonia, S.; Pluzanski, A.; Vokes, E.E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.S.K.; Wu, Y.-L.; Kudaba, I.; Kowalski, D.M.; Cho, B.C.; Turna, H.Z.; Castro, G., Jr.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Laktionov, K.K.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshow, D.B.; Bhalla, S.; Beasley, M.B.; Sholl, L.M.; Kerr, K.M.; Gnjatic, S.; Wistuba, I.I.; Rimm, D.L.; Tsao, M.S.; Hirsch, F.R. PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Stein, J.E.; Rimm, D.L.; Wang, D.W.; Bell, J.M.; Johnson, D.B.; Sosman, J.A.; Schalper, K.A.; Anders, R.A.; Wang, H. Comparison of Biomarker Modalities for Predicting Response to PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M.; Hopkins, A.; Jaffee, E.M. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2500–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paijens, S.T.; Vledder, A.; de Bruyn, M.; Nijman, H.W. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 842–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeckel, C.; Bakhl, K.; Georgakopoulos-Soares, I.; Zaravinos, A. The Efficacy of Tumor Mutation Burden as a Biomarker of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummel, K.; Eerkens, A.L.; de Bruyn, M.; Nijman, H.W. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: From prognosis to treatment selection. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemery, S.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. First FDA Approval Agnostic of Cancer Site—When a Biomarker Defines the Indication. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, T.; Shiu, K.-K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Chase, D.M.; Slomovitz, B.M.; Christensen, R.D.; Novák, Z.; Black, D.; Gilbert, L.; Sharma, S.; Valabrega, G.; Landrum, L.M.; et al. Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garralda, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Tabernero, J. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling for Drug Development in Oncology. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2017, 37, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyse, M.; Saad, E.D.; Burzykowski, T.; Regan, M.M.; Sweeney, C.S. Surrogacy Beyond Prognosis: The Importance of “Trial-Level” Surrogacy. Oncologist 2022, 27, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzykowski, T.; Buyse, M.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.J.; Sledge, G.; Carmichael, J.; Lück, H.-J.; Mackey, J.R.; Nabholtz, J.-M.; Paridaens, R.; Biganzoli, L.; et al. Evaluation of tumor response, disease control, progression-free survival, and time to progression as potential surrogate end points in metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, G.M.; Karuri, S.W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Knozin, S.; Kazandijan, D.; Tang, S.; Sridhara, R.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. Overall response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival with targeted and standard therapies in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: US Food and Drug Administration trial-level and patient-level analyses. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyse, M.; Thirion, P.; Carlson, R.W.; Burzykowski, T.; Molenberghs, G.; Piedbois, P. Relation between tumour response to first-line chemotherapy and survival in advanced colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Meta-Analysis Group in Cancer. Lancet 2000, 356, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michiels, S.; Pugliano, L.; Marguet, S.; Grun, D.; Barinoff, J.; Cameron, D.; Cobleigh, M.; Di Leo, A.; Johnston, S.; Gasparini, G.; et al. Progression-free survival as surrogate end point for overall survival in clinical trials of HER2-targeted agents in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oba, K.; Paoletti, X.; Alberts, S.; Bang, Y.-J.; Benedetti, J.; Bleiberg, H.; Catalano, P.; Lordick, F.; Michiels, S.; Morita, S.; et al. Disease-free survival as a surrogate for overall survival in adjuvant trials of gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, X.; Oba, K.; Bang, Y.-J.; Bleiberg, H.; Boku, N.; Bouché, O.; Catalano, P.; Fuse, N.; Michiels, S.; Moehler, M.; et al. Progression-free survival as a surrogate for overall survival in advanced/recurrent gastric cancer trials: A meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1667–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; de Gramont, A.; Grothey, A.; Zalcberg, J.; Chibaudel, B.; Schmoll, H.-J.; Seymour, M.T.; Adams, R.; Saltz, L.; Goldberg, R.M.; et al. Individual patient data analysis of progression-free survival versus overall survival as a first-line end point for metastatic colorectal cancer in modern randomized trials: Findings from the analysis and research in cancers of the digestive system database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Schwartz, L.H.; William, W.N.; Sznol, M.; Fahrbach, K.; Xu, Y.; Masson, E.; Vergara-Silva, A. Evaluation of classical clinical endpoints as surrogates for overall survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint blockers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 144, 2245–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.; Andre, F.; Venturini, S.; Pistilli, B.; Curigliano, G.; Cristofanilli, M.; Rosellini, P.; Generali, D. Response rate as a potential surrogate for survival and efficacy in patients treated with novel immune checkpoint inhibitors: A meta-regression of randomised prospective studies. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 86, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, X.; He, J. Endpoint surrogacy in oncological randomized controlled trials with immunotherapies: A systematic review of trial-level and arm-level meta-analyses. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goring, S.; Varol, N.; Waser, N.; Popoff, E.; Lozano-Ortega, G.; Lee, A.; Yuan, Y.; Eccles, L.; Tran, P.; Penrod, J.R. Correlations between objective response rate and survival-based endpoints in first-line advanced non-small cell lung Cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2022, 170, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.X.; Lin, Y.; Ferry, D.; Widau, R.C.; Saha, A. Surrogate end points for survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Immunotherapy 2022, 14, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Coinu, A.; Cabiddu, M.; Borgonovo, K.; Ghilardi, M.; Lonati, V.; Barni, S. Early analysis of surrogate endpoints for metastatic melanoma in immune checkpoint inhibitor trials. Medicine 2016, 95, e3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushti, S.L.; Mulkey, F.; Sridhara, R. Evaluation of Overall Response Rate and Progression-Free Survival as Potential Surrogate Endpoints for Overall Survival in Immunotherapy Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, B.P.; Barata, P.C.; Kanjanapan, Y.; Paller, C.J.; Perlmutter, J.; Pond, G.R.; Prowell, T.M.; Rubin, E.H.; Seymour, L.K.; Wages, N.A.; et al. Seamless Designs: Current Practice and Considerations for Early-Phase Drug Development in Oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, M.I.; Siu, L.L.; Pond, G.R.; Chen, E.X. Comparison of outcomes of phase II studies and subsequent randomized control studies using identical chemotherapeutic regimens. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 6982–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, E.D.; Paoletti, X.; Burzykowski, T.; Buyse, M. Precision medicine needs randomized clinical trials. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, J.; LaVange, L.M. Master Protocols to Study Multiple Therapies, Multiple Diseases, or Both. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumovitz, M.; Westin, S.N.; Salvo, G.; Zarifa, A.; Xu, M.; Yap, T.A.; Rodon, A.J.; Karp, D.D.; Abonofal, A.; Jazaeri, A.A.; et al. Phase II study of pembrolizumab efficacy and safety in women with recurrent small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lower genital tract. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.P.; Othus, M.; Chae, Y.K.; Giles, F.J.; Hansel, D.E.; Singh, P.P.; Fontaine, A.; Shah, M.H.; Kasi, A.; Al Baghdadi, T.; et al. A Phase II Basket Trial of Dual Anti-CTLA-4 and Anti-PD-1 Blockade in Rare Tumors (DART SWOG 1609) in Patients with Nonpancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tourneau, C.; Lee, J.J.; Siu, L.L. Dose escalation methods in phase I cancer clinical trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clertant, M. Early-Phase Oncology Trials: Why So Many Designs? J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3529–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Optimizing the Dosage of Human Prescription Drugs and Biological Products for the Treatment of Oncologic Diseases. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/164555/download (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Zirkelbach, J.F.; Shah, M.; Vallejo, J.; Cheng, J.; Ayyoub, A.; Liu, J.; Hudson, R.; Sridhara, R.; Ison, G.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; et al. Improving Dose-Optimization Processes Used in Oncology Drug Development to Minimize Toxicity and Maximize Benefit to Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3489–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, W.; Xie, M.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, N.; Li, P.; Liang, A.; Young, K.H.; Qian, W. Treatment-Related Adverse Events of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell (CAR T) in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Deaft Guidance for Industry. Considerations for the Development of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Products. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/156896/download (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Chmielowski, B. How Should We Assess Benefit in Patients Receiving Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy? J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 835–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazandjian, D.; Keegan, P.; Suzman, D.L.; Pazdur, R.; Blumenthal, G.M. Characterization of outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer treated with programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors past RECIST version 1.1-defined disease progression in clinical trials. Semin. Oncol. 2017, 44, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, G.H.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, C.W.; Yoon, S.; Chae, Y.K.; Tirumani, S.H.; Ramaiya, N.H. Comparison of RECIST 1.1 and iRECIST in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manitz, J.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Apolo, A.B.; Eggleton, S.P.; Bajars, M.; Bohnsack, O.; Gulley, J.L. Comparison of tumor assessments using RECIST 1.1 and irRECIST, and association with overall survival. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Motzer, R.J.; Hammers, H.J.; Redman, B.G.; Kuzel, T.M.; Tykodi, S.S.; Plimack, E.R.; Jiang, J.; Waxman, I.M.; Rini, B.I. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab in Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated Beyond Progression: A Subgroup Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Weber, J.S.; Larkin, J.; Atkinson, V.; Grob, J.-J.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Robert, C.; Márquez-Rodas, I.; McNeil, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated Beyond Progression: Analysis of 2 Phase 3 Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudier, B.; Motzer, R.J.; Sharma, P.; Wagstaff, J.; Plimack, E.R.; Hammers, H.J.; Donskov, F.; Gurney, H.; Sosman, J.A.; Zalewski, P.G.; et al. Treatment Beyond Progression in Patients with Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated with Nivolumab in CheckMate 025. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, T.M. Analysis of duration of response: A problem of oncology trials. Control Clin. Trials 1988, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, E.L.; Othus, M.; Chen, T.; Freidlin, B. Assessing treatment efficacy in the subset of responders in a randomized clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1640–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Tian, L.; Talukder, E.; Rothenberg, M.; Kim, D.H.; Wei, L.-J. Evaluating Treatment Effect Based on Duration of Response for a Comparative Oncology Study. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 874–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Adaptive Designs for Clinical Trials of Drugs and Biologics. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/78495/download (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Chow, S.C.; Chang, M. Adaptive design methods in clinical trials—A review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, E.L.; Freidlin, B. Adaptive Clinical Trials: Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Adaptive Design Elements. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.D.; Buyse, M. Statistical controversies in clinical research: End points other than overall survival are vital for regulatory approval of anticancer agents. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; De Wit, R.; Vaughn, D.J.; Fradet, Y.; Lee, J.-L.; Fong, L.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Climent, M.A.; Petrylak, D.P.; Choueiri, T.K.; et al. Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadian, A.P.; Santos, S.D.; Parshad, S.; Everest, L.; Cheung, M.C.; Chan, K.K. Quantifying the Survival Benefits of Oncology Drugs With a Focus on Immunotherapy Using Restricted Mean Survival Time. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.-J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawbi, H.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Lipson, E.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Matamala, L.; Gutiérrez, E.C.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H.J.; Lao, C.D.; De Menezes, J.J.; et al. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zichi, C.; Paratore, C.; Gargiulo, P.; Mariniello, A.; Reale, M.L.; Audisio, M.; Bungaro, M.; Caglio, A.; Gamba, T.; Perrone, F.; et al. Adoption of multiple primary endpoints in phase III trials of systemic treatments in patients with advanced solid tumours. A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Multiple Endpoints in Clinical Trials. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/162416/download (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Hoering, A.; Durie, B.; Wang, H.; Crowley, J. End points and statistical considerations in immuno-oncology trials: Impact on multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. 2017, 13, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Kuan, P.F. Comparison of the restricted mean survival time with the hazard ratio in superiority trials with a time-to-event end point. Pharm. Stat. 2018, 17, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhen, B.; Park, Y.; Zhu, B. Designing therapeutic cancer vaccine trials with delayed treatment effect. Stat. Med. 2017, 36, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’Hern, R.P. Restricted Mean Survival Time: An Obligatory End Point for Time-to-Event Analysis in Cancer Trials? J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3474–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.-K.; Morita, S.; Satoh, T.; Ryu, M.-H.; Chao, Y.; Kato, K.; Chung, H.C.; Chen, J.-S.; Muro, K.; Kang, W.K.; et al. Exploration of predictors of benefit from nivolumab monotherapy for patients with pretreated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: Post hoc subanalysis from the ATTRACTION-2 study. Gastric Cancer 2022, 25, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, M.M.; Werner, L.; Rao, S.; Gupte-Singh, K.; Hodi, F.S.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Kluger, H.M.; Larkin, J.; Postow, M.A.; Ritchings, C.; et al. Treatment-Free Survival: A Novel Outcome Measure of the Effects of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition—A Pooled Analysis of Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3350–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Fell, G.; Trippa, L.; Alexander, B.M. Violations of the proportional hazards assumption in randomized phase III oncology clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36 (Suppl. S15), 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D.P.; Fleming, T.R. A class of rank test procedures for censored survival data. Biometrika 1982, 69, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.S.; Leon, L.F. Estimation of treatment effects in weighted log-rank tests. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2017, 8, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, M.; Lakatos, E. Weighted log rank type statistics for comparing survival curves when there is a time lag in the effectiveness of treatment. Biometrika 1990, 77, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Prentice, R. Improved logrank-type tests for survival data using adaptive weights. Biometrics 2010, 66, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipkin, D.A.; Umscheid, C.A.; Keating, N.L.; Allen, E.; Aung, K.; Beyth, R.; Mann, D.M.; Sussman, J.B.; Korenstein, D. Evidence-based risk communication: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 161, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyse, M. Generalized pairwise comparisons of prioritized outcomes in the two-sample problem. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 3245–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péron, J.; Roy, P.; Ding, K.; Parulekar, W.R.; Roche, L.; Buyse, M. Assessing the benefit-risk of new treatments using generalised pairwise comparisons: The case of erlotinib in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péron, J.; Roy, P.; Ozenne, B.; Roche, L.; Buyse, M. The Net Chance of a Longer Survival as a Patient-Oriented Measure of Treatment Benefit in Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, S.J.; Ariti, C.A.; Collier, T.J.; Wang, D. The win ratio: A new approach to the analysis of composite endpoints in clinical trials based on clinical priorities. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, E.; Vandemeulebroecke, M.; Mutze, T. Win odds: An adaptation of the win ratio to include ties. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 3367–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Immune-Related Response Criteria [23] | Immune-Related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [34] | Immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [35] | Immune-Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [27] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Measurement | Bidimensional | Unidimensional | Unidimensional | Unidimensional |

| Characterization of the tumor burden | Measurements of up to 15 index lesions (up to 5/organ, up to 10 visceral and 5 cutaneous lesions) added to measurements of new, measurable lesions (≥5 × 5 mm; up to 5/organ, up to 10 visceral and 5 cutaneous lesions) to provide the total tumor burden | Measurements of target lesions (presumably following RECIST stipulations) added to measurements of new lesions to provide the sum of measurements | In addition to usual RECIST stipulations, new lesions are characterized as “new lesion target” and “new lesion non-target” (and not incorporated in the total tumor burden) | Measurements of target lesions (following RECIST stipulations) are added to measurements of new lesions (up to 5 in total and 2/organ) to provide total tumor burden; when not measurable, new lesions are not factored into the assessment of PD, unless they become measurable and the maximum of 5 measurable new lesions has not been reached |

| Definition of PD | Increase ≥ 25% in tumor burden compared with nadir (at any time point) in two consecutive observations at least 4 weeks apart; progression of non-index lesions does not define PD | Increase ≥ 20% in the sum of measurements compared with a nadir in two consecutive observations at least 4 weeks apart | PD can be assigned multiple times, as long as it is not confirmed 4–8 weeks later; if PD is not confirmed (i.e., tumor shrinkage is observed in comparison with baseline), the bar is reset so that it needs to occur again (compared with nadir) and then be confirmed | Increase ≥ 20% in total tumor burden compared with nadir in two consecutive observations at least 4 weeks apart; progression of non-target lesions does not define PD |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Restricted mean survival time | Additive properties; applicable even in the extreme cases of non-proportional hazards with initially overlapping or crossing survival functions; useful even when median survival is not reached | Dependence on truncation time; non-intuitive interpretation |

| Weighted logrank test | Higher statistical power in the same nonparametric framework as the logrank test | Potential bias from weight selection; ethical concern from a differential weighing of earlier and later events; loss of power if the shape of curves is incorrectly specified |

| Accelerated failure-time models | Interpretation in terms of the mean survival time (preferable to median survival time); robustness to omission of covariates; no parametric distributional assumptions in the case of semiparametric models | Unsuitable for the extreme cases of non-proportional hazards with initially overlapping or crossing survival functions |

| Net Treatment Benefit | Intuitively conveys probabilities on an absolute scale; allows different stakeholders to prioritize outcomes and thresholds of benefit; allows simultaneous assessment of several endpoints, including safety | Recently proposed, with uncertain acceptability by regulatory agencies; potential for bias when average follow-up is much shorter than the longest event time; properties such as the impact of censoring still under study; choice of priorities and clinical thresholds arbitrary |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saad, E.D.; Coart, E.; Deltuvaite-Thomas, V.; Garcia-Barrado, L.; Burzykowski, T.; Buyse, M. Trial Design for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Methodological Toolkit. Cancers 2023, 15, 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184669

Saad ED, Coart E, Deltuvaite-Thomas V, Garcia-Barrado L, Burzykowski T, Buyse M. Trial Design for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Methodological Toolkit. Cancers. 2023; 15(18):4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184669

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaad, Everardo D., Elisabeth Coart, Vaiva Deltuvaite-Thomas, Leandro Garcia-Barrado, Tomasz Burzykowski, and Marc Buyse. 2023. "Trial Design for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Methodological Toolkit" Cancers 15, no. 18: 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184669

APA StyleSaad, E. D., Coart, E., Deltuvaite-Thomas, V., Garcia-Barrado, L., Burzykowski, T., & Buyse, M. (2023). Trial Design for Cancer Immunotherapy: A Methodological Toolkit. Cancers, 15(18), 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184669