Dietary Considerations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Useful for Treatment of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Checkpoint Molecules | Cells Expressing Checkpoint Molecules | Checkpoint Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| PD-1 [13] | T cells | pembrolizumab nivolumab cemiplimab |

| B cells | ||

| Monocytes | ||

| TAMs | ||

| NK | ||

| DC | ||

| MDSCs | ||

| Tumor cells | ||

| PD-L1 [14] | Tumor cells | atezolizumab avelumab durvalumab |

| Monocytes | ||

| NK | ||

| CAFs | ||

| Macrophages | ||

| DCs | ||

| T cells | ||

| CTLA-4 [13] | T cells | ipilimumab |

| NK | ||

| LAG3 [13,15] | T cells | relatlimab |

| NK | ||

| Plasmacytoid DCs | ||

| TAMs | ||

| B Cells |

2. Epidemiology

3. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event Grading of CIC

4. Inflammatory Bowel Disease

5. CIC Similarities to IBD

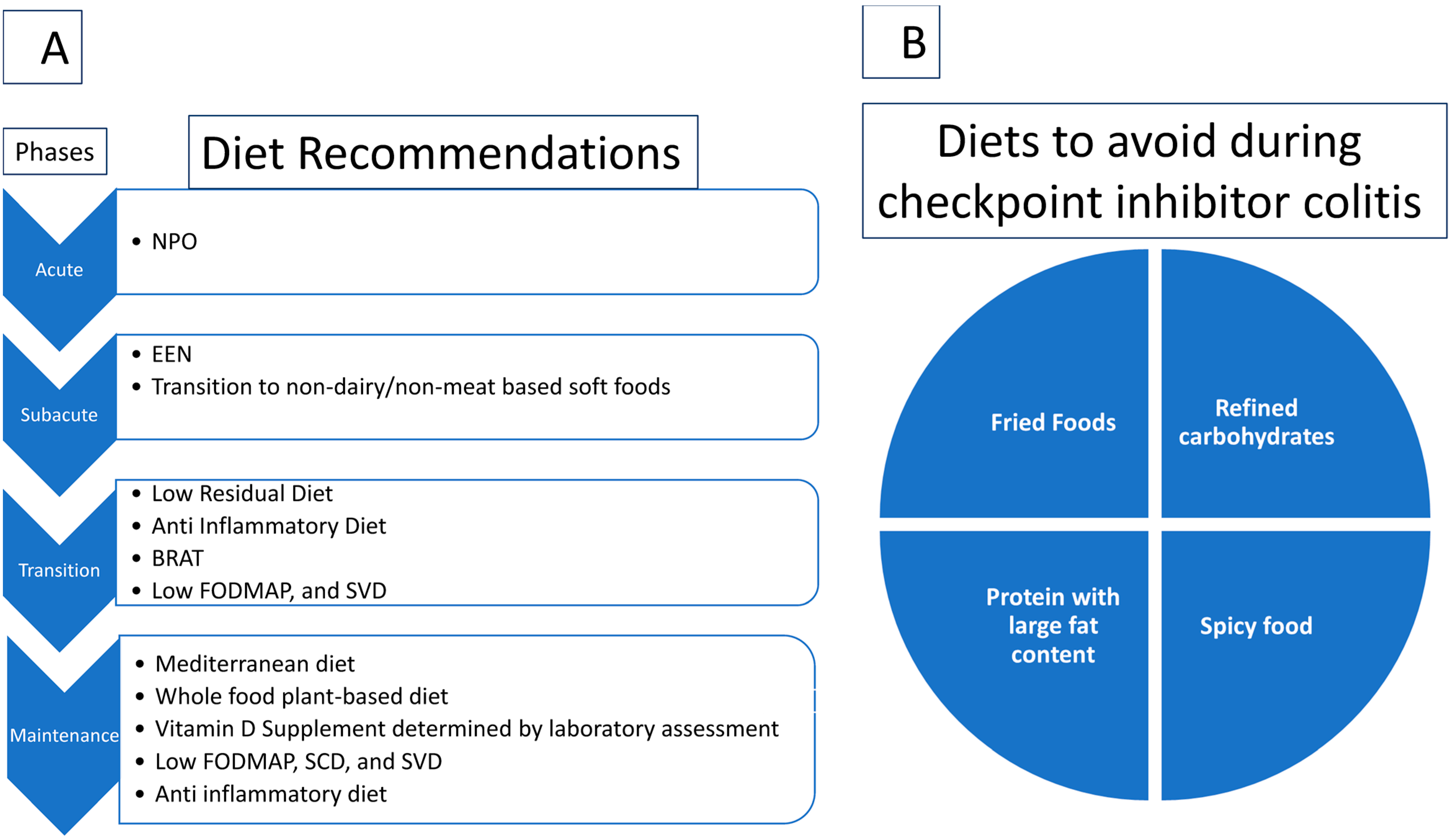

6. Role of Diets Recommended for IBD in Prevention and Treatment of CIC

6.1. Exclusive Enteral Nutrition for Active CD

6.2. Banana, Rice, Applesauce, and Toast (BRAT)

6.3. Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD)

6.4. Low Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAP) Diet

6.5. Semi-Vegetarian Diet and Whole Food Plant-Based Diet

6.6. Anti-Inflammatory Diet/Diet on Autoimmune Protocol

6.7. Mediterranean Diet

6.8. Low-Residue Diet

6.9. Dietary Supplements

7. Role of Diet Changes in Microbiota

8. Role of the Microbiome

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodman, A.M.; Piccioni, D.; Kato, S.; Boichard, A.; Wang, H.-Y.; Frampton, G.; Lippman, S.M.; Connelly, C.; Fabrizio, D.; Miller, V.; et al. Prevalence of PDL1 Amplification and Preliminary Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Solid Tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postow, M.A. Managing Immune Checkpoint-Blocking Antibody Side Effects. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2015, 35, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dine, J.; Gordon, R.; Shames, Y.; Kasler, M.K.; Barton-Burke, M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: An Innovation in Immunotherapy for the Treatment and Management of Patients with Cancer. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 4, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlino, M.S.; Larkin, J.; Long, G.V. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. Lancet 2021, 398, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashash, J.G.; Francis, F.F.; Farraye, F.A. Diagnosis and Management of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Dougan, M.; Wang, Y.; Rubio-Tapia, A.; Lim, J.K. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis and Hepatitis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Wang, Y. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Mediated Diarrhea and Colitis: A Clinical Review. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W.; Fuss, I.; Mannon, P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertha, M.; Bellaguara, E.; Kuzel, T.; Hanauer, S. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis: A New Type of Inflammatory Bowel Disease? ACG Case Rep. J. 2017, 4, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakavellas, S.I.; Bamias, G. Checkpoint inhibitor colitis: A new model of inflammatory bowel disease? Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 34, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.C.; Price, C.; Blenman, K.; Patil, P.; Zhang, X.; Robert, M.E. Checkpoint Inhibitor Colitis Shows Drug-Specific Differences in Immune Cell Reaction That Overlap With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Predict Response to Colitis Therapy. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 156, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Mao, E.; Ali, N.; Qiao, W.; Trinh, V.A.; Zobniw, C.; Johnson, D.H.; Samdani, R.; Lum, P.; et al. Endoscopic and Histologic Features of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Hogg, G.D.; DeNardo, D.G. Rethinking immune checkpoint blockade: ‘Beyond the T cell’. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.; Niu, M.; Xu, L.; Luo, S.; Wu, K. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graydon, C.G.; Mohideen, S.; Fowke, K.R. LAG3’s Enigmatic Mechanism of Action. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 615317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Lacchetti, C.; Schneider, B.J.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Gardner, J.M.; Ginex, P.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1714–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, N.; Zhou, Y.; He, W.; Liu, J.; Ma, X. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Colitis: From Mechanism to Management. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 800879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y.; Ye, F.; Zhao, S.; Johnson, D.B. Incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis in solid tumor patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. OncoImmunology 2017, 6, e1344805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Grob, J.-J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Wagstaff, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Ferrucci, P.F.; et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Kähler, K.; Hauschild, A. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events and Kinetics of Response With Ipilimumab. J. Clin. Oncol. (JCO) 2012, 30, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Blank, C.U.; Mandala, M.; Long, G.V.; Atkinson, V.; Dalle, S.; Haydon, A.; Lichinitser, M.; Khattak, A.; Carlino, M.S.; et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage III Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1789–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.; Mandala, M.; Del Vecchio, M.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.M.; Cowey, C.L.; Dalle, S.; Schenker, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Grob, J.-J.; Dummer, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Schmidt, H.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ascierto, P.A.; Richards, J.M.; et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebbé, C.; Meyer, N.; Mortier, L.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; Robert, C.; Rutkowski, P.; Menzies, A.M.; Eigentler, T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Smylie, M.; et al. Evaluation of Two Dosing Regimens for Nivolumab in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma: Results From the Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 511 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawbi, H.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Lipson, E.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Matamala, L.; Castillo Gutiérrez, E.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H.J.; Lao, C.D.; De Menezes, J.J.; et al. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grob, J.-J.; Gonzalez, R.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Vornicova, O.; Schachter, J.; Joshi, A.; Meyer, N.; Grange, F.; Piulats, J.M.; Bauman, J.R.; et al. Pembrolizumab Monotherapy for Recurrent or Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Single-Arm Phase II Trial (KEYNOTE-629). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2916–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migden, M.R.; Khushalani, N.I.; Chang, A.L.S.; Lewis, K.D.; Schmults, C.D.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Meier, F.; Schadendorf, D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Sekulic, A.; Peris, K.; Bechter, O.; Prey, S.; Kaatz, M.; Lewis, K.D.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Chang, A.L.S.; Dalle, S.; et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog inhibitor therapy: An open-label, multi-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, P.T.; Bhatia, S.; Lipson, E.J.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; Miller, N.J.; Annamalai, L.; Berry, S.; Chartash, E.K.; Daud, A.; Fling, S.P.; et al. PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 2542–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.P.; Russell, J.; Lebbé, C.; Chmielowski, B.; Gambichler, T.; Grob, J.-J.; Kiecker, F.; Rabinowits, G.; Terheyden, P.; Zwiener, I.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of First-line Avelumab Treatment in Patients With Stage IV Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Preplanned Interim Analysis of a Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, e180077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthey, L.; Mateus, C.; Mussini, C.; Nachury, M.; Nancey, S.; Grange, F.; Zallot, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Rahier, J.F.; Bourdier de Beauregard, M.; et al. Cancer Immunotherapy with Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies Induces an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Dougan, M.; Tyan, K.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Blum, S.M.; Ishizuka, J.; Qazi, T.; Elias, R.; Vora, K.B.; Ruan, A.B.; et al. Vitamin D intake is associated with decreased risk of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Cancer 2020, 126, 3758–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga Neto, M.B.; Ramos, G.P.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Faubion, W.A.; Raffals, L.E. Use of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Patients With Pre-established Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Retrospective Case Series. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1285–1287.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Ruan, A.B.; Srivoleti, P.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Braschi-Amirfarzan, M.; Srivastava, A.; Buchbinder, E.I.; Ott, P.A.; Kehl, K.L.; Awad, M.M.; et al. Safety of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Patients With Pre-Existing Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Microscopic Colitis. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e933–e942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Som, A.; Mandaliya, R.; Alsaadi, D.; Farshidpour, M.; Charabaty, A.; Malhotra, N.; Mattar, M.C. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: A comprehensive review. World J. Clin. Cases 2019, 7, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Brahmer, J.R.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Ascierto, P.A.; Brufsky, J.; Cappelli, L.C.; Cortazar, F.B.; Gerber, D.E.; Hamad, L.; Hansen, E.; Johnson, D.B.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. J. ImmunoTherapy Cancer 2021, 9, e002435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-J.; Chiu, Y.-T.; Chiu, C.-T.; Lin, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Hsieh, J.-Y.; Wei, S.-C. Inflammatory bowel disease and its treatment in 2018: Global and Taiwanese status updates. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.; Farooq, U.; MuhammadHaseeb, M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. [Updated 2022 May 1]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470312/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Shanahan, F. Inflammatory bowel disease: Immunodiagnostics, immunotherapeutics, and ecotherapeutics. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolsky, D.K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 325, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, D.C.; Carding, S.R. Inflammatory bowel disease: Cause and immunobiology. Lancet 2007, 369, 1627–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchmann, R.; Kaiser, I.; Hermann, E.; Mayet, W.; Ewe, K.; Meyer zum Büschenfelde, K.H. Tolerance exists towards resident intestinal flora but is broken in active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1995, 102, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zoeten, E.F.; Pasternak, B.A.; Mattei, P.; Kramer, R.E.; Kader, H.A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Perianal Crohn Disease: NASPGHAN Clinical Report and Consensus Statement. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maaser, C.; Sturm, A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Kucharzik, T.; Fiorino, G.; Annese, V.; Calabrese, E.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bettenworth, D.; Borralho Nunes, P.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 13, 144–164K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langner, C.; Magro, F.; Driessen, A.; Ensari, A.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Villanacci, V.; Becheanu, G.; Borralho Nunes, P.; Cathomas, G.; Fries, W.; et al. The histopathological approach to inflammatory bowel disease: A practice guide. Virchows Arch. 2014, 464, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, W.R.; Becktel, J.M.; Singleton, J.W.; Kern, F., Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology 1976, 70, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, J.Y.; Modigliani, R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn’s disease: A prospective multicentre study. Groupe d’Etudes Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Gut 1989, 30, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.W.; Tremaine, W.J.; Ilstrup, D.M. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.J.; Lobo, A.J.; Travis, S.P.L. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2004, 53, v1–v16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prantera, C.; Viscido, A.; Biancone, L.; Francavilla, A.; Giglio, L.; Campieri, M. A new oral delivery system for 5-ASA: Preliminary clinical findings for MMx. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005, 11, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Haas, C.T.; Pele, L.C.; Monie, T.P.; Charalambos, C.; Parkes, M.; Hewitt, R.E.; Powell, J.J. Intestinal APCs of the endogenous nanomineral pathway fail to express PD-L1 in Crohn’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, C.A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Raine, T.; Hendy, P.A.; Smith, P.J.; Limdi, J.K.; Hayee, B.H.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Parkes, G.C.; Selinger, C.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019, 68, s1–s106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanauer, S.B.; Strömberg, U. Oral Pentasa in the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: A meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 2, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prefontaine, E.; Sutherland, L.R.; Macdonald, J.K.; Cepoiu, M. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, CD000067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, A.; McDonald, J.W.; Tsoulis, D.J.; Macdonald, J.K. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD000478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Qiao, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dai, S.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, X. Tumor necrosis factor alpha blocking agents as treatment for ulcerative colitis intolerant or refractory to conventional medical therapy: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deventer, S.J.H. Anti-TNF antibody treatment of Crohn’s disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1999, 58, I114–I120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Su, C.; Sands, B.E.; D’Haens, G.R.; Vermeire, S.; Schreiber, S.; Danese, S.; Feagan, B.G.; Reinisch, W.; Niezychowski, W.; et al. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1723–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Roda, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Evolving therapeutic goals in ulcerative colitis: Towards disease clearance. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, G.R.; Rutgeerts, P. Importance of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 16, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.V.; Winer, S.; SPL, T.; Riddell, R.H. Systematic review: Histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 1582–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Jangi, S.; Dulai, P.S.; Boland, B.S.; Jairath, V.; Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Singh, S. Histologic Remission Is Associated With Lower Risk of Treatment Failure in Patients With Crohn Disease in Endoscopic Remission. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Bressenot, A.; Kampman, W. Histologic remission: The ultimate therapeutic goal in ulcerative colitis? Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 929–934.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, S.A.; Mani, V.; Goodman, M.J.; Dutt, S.; Herd, M.E. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: What does it mean? Gut 1991, 32, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.A.; Schneider, B.J.; Brahmer, J.; Achufusi, A.; Armand, P.; Berkenstock, M.K.; Bhatia, S.; Budde, L.E.; Chokshi, S.; Davies, M.; et al. Management of Immunotherapy-Related Toxicities, Version 1.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Siddiqui, B.A.; Anandhan, S.; Yadav, S.S.; Subudhi, S.K.; Gao, J.; Goswami, S.; Allison, J.P. The Next Decade of Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 838–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.T. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2652–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Ni, J.; Xu, W.D.; Wen, P.F.; Qiu, L.J.; Wang, X.S.; Pan, H.F.; Ye, D.Q. Association of CTLA-4 variants with susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis. Hum. Immunol. 2014, 75, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Qiu, L.-J.; Zhang, M.; Wen, P.-F.; Ye, X.-R.; Liang, Y.; Pan, H.-F.; Ye, D.-Q. CTLA-4 CT60 (rs3087243) polymorphism and autoimmune thyroid diseases susceptibility: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Endocr. Res. 2014, 39, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, C.; Gabrysch, A.; Olbrich, P.; Patiño, V.; Warnatz, K.; Wolff, D.; Hoshino, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Imai, K.; Takagi, M.; et al. Phenotype, penetrance, and treatment of 133 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4-insufficient subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, M.R.; Aslani, S.; Salmaninejad, A.; Javan, M.R.; Rezaei, N. PD-1/PD-L and autoimmunity: A growing relationship. Cell Immunol. 2016, 310, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, J.J.; Thomas-McKay, E.; Thoree, V.; Robertson, J.; Hewitt, R.E.; Skepper, J.N.; Brown, A.; Hernandez-Garrido, J.C.; Midgley, P.A.; Gomez-Morilla, I.; et al. An endogenous nanomineral chaperones luminal antigen and peptidoglycan to intestinal immune cells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Samdani, R.; Nogueras Gonzalez, G.; Raju, G.S.; Richards, D.M.; Gao, J.; Subudhi, S.; Stroehlein, J.; Wang, Y. Can Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Induce Microscopic Colitis or a Brand New Entity? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone Lopez, S.; Kats-Ugurlu, G.; Renken, R.J.; Buikema, H.J.; de Groot, M.R.; Visschedijk, M.C.; Dijkstra, G.; Jalving, M.; de Haan, J.J. Immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment induces colitis with heavy infiltration of CD8 + T cells and an infiltration pattern that resembles ulcerative colitis. Virchows Arch. 2021, 479, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geukes Foppen, M.H.; Rozeman, E.A.; van Wilpe, S.; Postma, C.; Snaebjornsson, P.; van Thienen, J.V.; van Leerdam, M.E.; van den Heuvel, M.; Blank, C.U.; van Dieren, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: Symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open 2018, 3, e000278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer, N. Version 1.2022—28 February 2022. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/immunotherapy.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Zou, F.; Wang, X.; Glitza Oliva, I.C.; McQuade, J.L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.C.; Thompson, J.A.; Thomas, A.S.; Wang, Y. Fecal calprotectin concentration to assess endoscopic and histologic remission in patients with cancer with immune-mediated diarrhea and colitis. J. ImmunoTherapy Cancer 2021, 9, e002058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddavide, R.; Rotolo, O.; Caruso, M.G.; Stasi, E.; Notarnicola, M.; Miraglia, C.; Nouvenne, A.; Meschi, T.; De’ Angelis, G.L.; Di Mario, F.; et al. The role of diet in the prevention and treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Acta Biomed. 2018, 89, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voitk, A.J.; Echave, V.; Feller, J.H.; Brown, R.A.; Gurd, F.N. Experience with elemental diet in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Is this primary therapy? Arch. Surg. 1973, 107, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, N.H.; Manaf, Z.A.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Raja Ali, R.A. Anti-inflammatory diet and inflammatory bowel disease: What clinicians and patients should know? Intest. Res. 2021, 19, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricour, C.; Duhamel, J.F.; Nihoul-Fekete, C. Use of parenteral and elementary enteral nutrition in the treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in children. Arch. Fr. De Pediatr. 1977, 34, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Lochs, H.; Steinhardt, H.J.; Klaus-Wentz, B.; Zeitz, M.; Vogelsang, H.; Sommer, H.; Fleig, W.E.; Bauer, P.; Schirrmeister, J.; Malchow, H. Comparison of enteral nutrition and drug treatment in active Crohn’s disease. Results of the European Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. IV. Gastroenterology 1991, 101, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, N.; Miller, T.; Suskind, D.; Lee, D. A Review of Dietary Therapy for IBD and a Vision for the Future. Nutrients 2019, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarian, L.F. A Synopsis of the American Academy of Pediatrics’Practice Parameter on the Management of Acute Gastroenteritis in Young Children. Pediatr. Rev. 1997, 18, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Ross, V.; Mahadevan, U. Popular exclusionary diets for inflammatory bowel disease: The search for a dietary culprit. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, T.C.; Fiebig-Comyn, A.A.; Shaler, C.R.; McPhee, J.B.; Coombes, B.K.; Schertzer, J.D. Low dietary fiber promotes enteric expansion of a Crohn’s disease-associated pathobiont independent of obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 321, E338–E350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijeti, G.G.; Kim, N.; Lewis, J.D.; Groven, S.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Grandhe, S.; Diamant, C.; Singh, E.; Oliveira, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 2054–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.R.; Shepherd, S.J. Personal view: Food for thought--western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, A.C.; Myers, C.E.; Joyce, T.; Irving, P.; Lomer, M.; Whelan, K. Fermentable Carbohydrate Restriction (Low FODMAP Diet) in Clinical Practice Improves Functional Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Abe, T.; Tsuda, H.; Sugawara, T.; Tsuda, S.; Tozawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Imai, H. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2484–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, F.; Magri, S.; Cingolani, A.; Paduano, D.; Pesenti, M.; Zara, F.; Tumbarello, F.; Urru, E.; Melis, A.; Casula, L.; et al. Multidimensional Impact of Mediterranean Diet on IBD Patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschall, E.G. Breaking the Vicious Cycle: Intestinal Health through Diet; Kirkton Press: West Perth, ON, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur, K.; Kahleova, H.; Desmond, A.N.; Elfrink, E.; Barnard, N.D. Crohn’s Disease Remission with a Plant-Based Diet: A Case Report. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obih, C.; Wahbeh, G.; Lee, D.; Braly, K.; Giefer, M.; Shaffer, M.L.; Nielson, H.; Suskind, D.L. Specific carbohydrate diet for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice within an academic IBD center. Nutrition 2016, 32, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.D.; Sandler, R.S.; Brotherton, C.; Brensinger, C.; Li, H.; Kappelman, M.D.; Daniel, S.G.; Bittinger, K.; Albenberg, L.; Valentine, J.F.; et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Specific Carbohydrate Diet to a Mediterranean Diet in Adults With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 837–852.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.K.; Lee, D.; Lewis, J. Diet and inflammatory bowel disease: Review of patient-targeted recommendations. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiguchi, R.; Basu, S.; Staab, H.A.; Ito, N.; Zhou, X.K.; Wang, H.; Ha, T.; Johncilla, M.; Yantiss, R.K.; Montrose, D.C.; et al. Dietary interventions to prevent high-fructose diet-associated worsening of colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice. Carcinogenesis 2021, 42, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.; Dong, H.; Chen, Z.; Jin, M.; Yin, J.; Li, H.; Shi, D.; Shao, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota Mediates High-Fructose and High-Fat Diets to Induce Chronic Intestinal Inflammation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Nakane, K.; Tsuji, T.; Tsuda, S.; Ishii, H.; Ohno, H.; Watanabe, K.; Ito, M.; Komatsu, M.; Yamada, K.; et al. Relapse Prevention in Ulcerative Colitis by Plant-Based Diet Through Educational Hospitalization: A Single-Group Trial. Perm. J. 2018, 22, 17–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, O.; Studd, C.; Wilson, J.; Williams, J.; Hair, C.; Knight, R.; Prewett, E.; Dabkowski, P.; Alexander, S.; Allen, B.; et al. Influence of food and lifestyle on the risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease. Intern. Med. J. 2016, 46, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisshof, R.; Chermesh, I. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.; Cooper, S.C.; Ghosh, S.; Hewison, M. The Role of Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanism to Management. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, M.; Milestone, A.N.; Walters, J.R.; Hart, A.L.; Ghosh, S. Vitamin D and gastrointestinal diseases: Inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2011, 4, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresner-Pollak, R.; Ackerman, Z.; Eliakim, R.; Karban, A.; Chowers, Y.; Fidder, H.H. The BsmI Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphism Is Associated with Ulcerative Colitis in Jewish Ashkenazi Patients. Genet. Test. 2004, 8, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantorna, M.T.; Munsick, C.; Bemiss, C.; Mahon, B.D. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol prevents and ameliorates symptoms of experimental murine inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2648–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, N.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Gong, X. Efficacy of vitamin D in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, K.; Nakamura, M.; Odahara, S.; Koido, S.; Katahira, K.; Shiraishi, H.; Ohkusa, T.; Fujise, K.; Tajiri, H. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diet therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabré, E.; Mañosa, M.; Gassull, M.A. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory bowel diseases—A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107 (Suppl. S2), S240–S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagan, B.G.; Sandborn, W.J.; Mittmann, U.; Bar-Meir, S.; D’Haens, G.; Bradette, M.; Cohen, A.; Dallaire, C.; Ponich, T.P.; McDonald, J.W.D.; et al. Omega-3 Free Fatty Acids for the Maintenance of Remission in Crohn Disease: The EPIC Randomized Controlled Trials. JAMA 2008, 299, 1690–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, O.M.; Garces, L.; Abreu, M.T. Diet as Adjunctive Treatment for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Review and Update of the Latest Literature. Curr. Treat. Opt. Gastroenterol. 2019, 17, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simadibrata, M.; Halimkesuma, C.C.; Suwita, B.M. Efficacy of Curcumin as Adjuvant Therapy to Induce or Maintain Remission in Ulcerative Colitis Patients: An Evidence-based Clinical Review. Acta Med. Indones. 2017, 49, 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R.; Penmetsa, A.; Medaboina, K.; Boramma, G.G.; Amsrala, S.; Reddy, D.N. Novel Bio-Enhanced Curcumin with Mesalamine for Induction of Remission in Mild to Moderate Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, S587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Torbenson, M.; Hamad, A.R.; Soloski, M.J.; Li, Z. High-fat diet modulates non-CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells and regulatory T cells in mouse colon and exacerbates experimental colitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008, 151, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitcher, M.C.; Cummings, J.H. Hydrogen sulphide: A bacterial toxin in ulcerative colitis? Gut 1996, 39, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.N.; McQuade, J.L.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; McCulloch, J.A.; Vetizou, M.; Cogdill, A.P.; Khan, M.A.W.; Zhang, X.; White, M.G.; Peterson, C.B.; et al. Dietary fiber and probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response. Science 2021, 374, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentella, M.C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Pizzoferrato, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miggiano, G.A.D. Nutrition, IBD and Gut Microbiota: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubrovsky, A.; Kitts, C.L. Effect of the Specific Carbohydrate Diet on the Microbiome of a Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Ulcerative Colitis Patient. Cureus 2018, 10, e2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervier, K.; Moss, S.; Kumar, N.; Adoum, A.; Barne, M.; Browne, H.; Kaser, A.; Kiely, C.J.; Neville, B.A.; Powell, N.; et al. Two microbiota subtypes identified in irritable bowel syndrome with distinct responses to the low FODMAP diet. Gut 2022, 71, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, A.; Bukovsky, I.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Alwarith, J.; Barnard, N.D.; Kahleova, H. The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vétizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillère, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.L.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Cutaneous Malignancy | Immunotherapy | Diarrhea | Colitis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade ≤ 2 | Grade ≥ 3 | Grade ≤ 2 | Grade ≥ 3 | ||

| Melanoma | Pembrolizumab (Keynote-054) [21] * | 18.3% | 0.8% | 1.7% | 2% |

| Nivolumab (Checkmate-238) [22] * | 22.8% | 1.5% | 1.3% | 0.7% | |

| Ipilimumab (EORTC-18071) [23] | 39% | 10% | 8% | 7% | |

| Ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) + Nivo (1 mg/kg) (Checkmate-511) [24] * | 24.7% | 6.2% | 0.6% | 4.5% | |

| Ipilimumab (1 mg/kg) + Nivolumab (3 mg/kg) (Checkmate-511) [24] * | 23.3% | 2.8% | 1.7% | 2.2% | |

| Nivolumab + Relatlimab (Relativity-047) [25] * | 12.7% | 0.8% | 5.7% | 1.1% | |

| SCC | Pembrolizumab (Keynote-629) [26] * | 9.4% | 0% | 0% | 1.3% |

| Cemiplimab [27] | 27% | 0% | -* | -* | |

| BCC | Cemiplimab [28] | 24% | 0% | 0% | 5% |

| MCC | Pembrolizumab (Keynote 017) [29] * | 3.8% | 0% | -* | -* |

| Avelumab [30] | 5.1% | 0% | -* | -* | |

| Diet | Contents | Use in CIC |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusive enteral nutrition [81,82,83,84,85] | Formula consisting of hydrolysate, synthetic amino acid, digestible fat, sucrose, vitamin, mineral dissolved in water | Subacute |

| BRAT [86] | Banana, rice, applesauce, and toast | Transition |

| Low-Residual Diet [87,88] | Excludes high-fiber foods, such as whole-grain breads, cereals, nuts, fruits, and vegetables. | Transition |

| Anti-Inflammatory Diet [89] | Includes fresh nutrient-dense food such as fruits, freshly cooked vegetables, fish or meat, bone broth, and fermented food | Transition/Maintenance |

| Low FODMAP [90,91] | Excludes foods such as fruits, corn syrup, milk, yogurt, honey, wheat, onions, apple, pears, legumes, beans, and other similar products. | Transition/Maintenance |

| Semi-Vegetarian Diet [92] | Includes mostly fresh fruits and vegetables with weekly fish and biweekly meat | Transition/Maintenance |

| Mediterranean Diet [93] | Includes vegetables, fruits, cereals, nuts, legumes, unsaturated fat (e.g., olive oil), a medium intake of fish, dairy products, wine, and a low consumption of saturated fat, meat, and sweets | Maintenance |

| Specific Carbohydrate Diet [94] | Includes monosaccharides such as fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, honey, meat, and fish. Excludes complex carbohydrates such as grains and dairy. | Maintenance |

| Whole food plant-based diet [95] | Includes fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grain foods without any animal product, including dairy, eggs, food emulsifiers, artificial flavors, omega 6 fatty acid, and any processed food | Maintenance |

| Diet | Abundance of Bacterial Species |

|---|---|

| High-Fiber Diet [80,115,118] | Ruminococcaceae species, Prevotella, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria |

| Meditarranean Diet [93,119] | Lacnospira, L. ruminococcus species, Bacteroidetes, Clostridium cluster IV, and XIVa |

| Specific Carbohydrate Diet [119,120] | Enterobacter species, including Escherichia, Clostridia, Gammaproteobacteria |

| Low FODMAP Diet [119,121] | Bacteroides, Clostridium cluster XIVa, Akkermansia muciniphilia |

| Whole Food Plant-Based Diet [122] | Prevotella, Ruminococcus |

| Bacterial Species | Effect of Immunotherapy |

|---|---|

| Bacteroides fragillis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, and Burkholderiales | Increase efficacy of CTLA-4 inhibitors [123] |

| Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium longum, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Augment effect of anti-PD-L1 inhibitors [124] |

| Ruminococcaceae species and Faecalibacterium species | High-fiber diet increases efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy [118,125] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saha, A.; Dreyfuss, I.; Sarfraz, H.; Friedman, M.; Markowitz, J. Dietary Considerations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Useful for Treatment of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. Cancers 2023, 15, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010084

Saha A, Dreyfuss I, Sarfraz H, Friedman M, Markowitz J. Dietary Considerations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Useful for Treatment of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. Cancers. 2023; 15(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaha, Aditi, Isabella Dreyfuss, Humaira Sarfraz, Mark Friedman, and Joseph Markowitz. 2023. "Dietary Considerations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Useful for Treatment of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis" Cancers 15, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010084

APA StyleSaha, A., Dreyfuss, I., Sarfraz, H., Friedman, M., & Markowitz, J. (2023). Dietary Considerations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Are Useful for Treatment of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. Cancers, 15(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15010084