Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology: Basic Principles

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. PPC in Oncology: Basic Principles

2.1. The Evolving Scenario of Pediatric Oncology

2.2. Basic Principles of PPC and Their Application in Pediatric Oncology

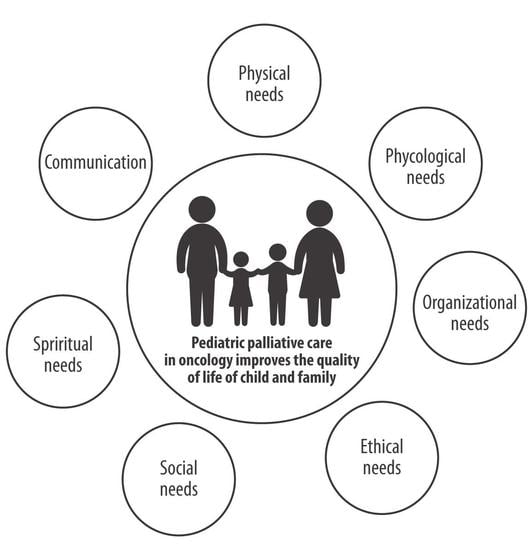

3. Needs in Pediatric Oncology

3.1. Child Needs

3.2. Family Needs

3.3. Communication Needs

3.4. Ethical Needs

3.5. Team Needs

4. Models of PPC in Oncology

5. End-of-Life Care and Advanced Care Planning

5.1. Basic Principles and Symptom Management

5.2. Advanced Care Planning

5.3. After Death Care

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Connor, S.R.; Downing, J.; Marston, J. Estimating the global need for palliative care for children: A cross-sectional analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Make Every Child Count. Available online: https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/resource/make-every-child-count/ (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Feudtner, C.; Kang, T.I.; Hexem, K.R.; Friedrichsdorf, S.J.; Osenga, K.; Siden, H.; Friebert, S.E.; Hays, R.M.; Dussel, V.; Wolfe, J. Pediatric palliative care patients: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 094–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief in Paediatrics. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274561 (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Benini, F.; Pappadatou, D.; Bernadá, M.; Craig, F.; De Zen, L.; Downing, J.; Drake, R.; Freidrichsdorf, S.; Garros, D.; Giacomelli, L.; et al. International standards for pediatric palliative care: From IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, e529–e543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaman, J.; McCarthy, S.; Wiener, L.; Wolfe, J. Pediatric palliative care in oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salins, N.; Hughes, S.; Preston, N. Palliative Care in paediatric oncology: An update. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Weaver, M.S.; DeWitt, L.H.; Byers, E.; Stevens, S.E.; Lukowski, J.; Shih, B.; Zalud, K.; Applegarth, J.; Wong, H.N.; et al. The impact of specialty palliative care in pediatric oncology: A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 1060–1079.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsdorf, S.J.; Postier, A.; Dreyfus, J.; Osenga, K.; Sencer, S.; Wolfe, J. Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaman, J.M.; Kaye, E.C.; Lu, J.J.; Sykes, A.; Baker, J.N. Palliative care involvement is associated with less intensive end-of-life care in adolescent and young adult oncology patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim-Malpass, J.; Erickson, J.M.; Malpass, H.C. End-of-life care characteristics for young adults with cancer who die in the hospital. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuviello, A.; Raisanen, J.C.; Donohue, P.K.; Wiener, L.; Boss, R.D. Defining the boundaries of palliative care in pediatric oncology. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 1033–1042.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.T.; Rost, M.; De Clercq, E.; Arnold, L.; Elger, B.S.; Wangmo, T. Palliative care initiation in pediatric oncology patients: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.A.; Knapp, C.; Madden, V.; Shenkman, E. Pediatricians’ perceptions of and preferred timing for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e777–e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Woods, C.; Kennedy, K.; Velrajan, S.; Gattas, M.; Bilbeisi, T.; Huber, R.; Lemmon, M.E.; Baker, J.N.; Mack, J.W. Communication around palliative care principles and advance care planning between oncologists, children with advancing cancer and families. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 125, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benini, F.; Orzalesi, M.; de Santi, A.; Congedi, S.; Lazzarin, P.; Pellegatta, F.; De Zen, L.; Spizzichino, M.; Alleva, E. Barriers to the development of pediatric palliative care in Italy. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2016, 52, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, B.S.; Movsisyan, N.; Batmunkh, T.; Kumirova, E.; Borisevich, M.V.; Kirgizov, K.; Graetz, D.E.; McNeil, M.J.; Yakimkova, T.; Vinitsky, A.; et al. Barriers to the early integration of palliative care in pediatric oncology in 11 Eurasian countries. Cancer 2020, 126, 4984–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisio, K.N.; Levy, C.D.; Lewis, A.M.; Schultz, C.L. Attitudes and practices of pediatric oncologists regarding palliative care consultation for pediatric oncology patients. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogetz, J.F.; Root, M.C.; Purser, L.; Torkildson, C. Comparing health care provider-perceived barriers to pediatric palliative care fifteen years ago and today. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drach, L.L.; Cook, M.; Shields, S.; Burger, K.J. Changing the culture of pediatric palliative care at the bedside. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2021, 23, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, K.L.; Santos, G.; Ciapponi, A.; Comandé, D.; Bilodeau, M.; Wolfe, J.; Dussel, V. Impact of specialized pediatric palliative care: A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 339–364.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benini, F.; Cauzzo, C.; Congedi, S.; Da Dalt, L.; Cogo, P.; Biscaglia, L.; Giacomelli, L. Training in pediatric palliative care in Italy: Still much to do. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2019, 55, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, N.; Force, L.M.; Allemani, C.; Atun, R.; Bray, F.; Coleman, M.P.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Frazier, A.L.; Robison, L.L.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; et al. Childhood cancer burden: A review of global estimates. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e42–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.M.; Link, M.P.; Simone, J.V. Milestones in the curability of pediatric cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, D.W.; Gavin, A.T. Mortality among children and young people who survive cancer in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med. J. 2016, 85, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E.; DeSantis, C.; Robbins, A.; Kohler, B.; Jemal, A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaman, J.M.; Kaye, E.C.; Baker, J.N.; Wolfe, J. Pediatric palliative oncology: The state of the science and art of caring for children with cancer. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2018, 30, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Wolfe, J. Approaching the third decade of paediatric palliative oncology investigation: Historical progress and future directions. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2017, 1, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattner, P.; Strobel, H.; Khoshnevis, N.; Grunert, M.; Bartholomae, S.; Pruss, M.; Fitzel, R.; Halatsch, M.E.; Schilberg, K.; Siegelin, M.D.; et al. Compare and contrast: Pediatric cancer versus adult malignancies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, M.; De Zen, L.; Pellegatta, F.; Lazzarin, P.; Bertolotti, M.; Manfredini, L.; Aprea, A.; Memo, L.; Del Vecchio, A.; Agostiniani, R.; et al. A consensus conference report on defining the eligibility criteria for pediatric palliative care in Italy. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Rubenstein, J.; Levine, D.; Baker, J.N.; Dabbs, D.; Friebert, S.E. Pediatric palliative care in the community. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, C.; Lynch, C.; Donea, O.; Javier, R.; Clark, D. EAPC Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe 2013. Available online: https://www.rehpa.dk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/EAPC-Atlas-of-Pallaitive-Care-in-Europe-2013-webudgave.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Downing, J.; Ling, J.; Benini, F.; Payne, S.; Papadatou, D. A summary of the EAPC White Paper on core competencies for education in paediatric palliative care. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2014, 21, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Quill, T.E.; Abernethy, A.P. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1173–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, K.E.; Snaman, J.M.; Kaye, E.C.; Bower, K.A.; Weaver, M.S.; Baker, J.N.; Wolfe, J.; Ullrich, C. Models of pediatric palliative oncology outpatient care-benefits, challenges, and opportunities. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics 2000, 106, 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, P.H.; De Castro Molina, J.A.; Teo, K.; Tan, W.S. Paediatric palliative care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs: Evaluation of a home-based program. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, E.C.; Friebert, S.; Baker, J.N. Early integration of palliative care for children with high-risk cancer and their families. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstraesser, E.; Hain, R.D.; Pereira, J.L. The development of an instrument that can identify children with palliative care needs: The Paediatric Palliative Screening Scale (PaPaS Scale): A qualitative study approach. BMC Palliat. Care 2013, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.G.; Kwon, S.Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Kim, M.S.; Jeong, S.H.; Hahn, S.M.; Han, K.T.; Park, S.J.; Choi, J.Y. Paediatric palliative screening scale as a useful tool for clinicians’ assessment of palliative care needs of pediatric patients: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriastuti, M.; Halim, P.G.; Kusrini, E.; Bangun, M. Correlation of pediatric palliative screening scale and quality of life in pediatric cancer patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2020, 26, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarin, P.; Giacomelli, L.; Terrenato, I.; Benini, F.; on behalf of the ACCAPED Study Group. A tool for the evaluation of clinical needs and eligibility to pediatric palliative care: The validation of the ACCAPED scale. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.E.; Raybin, J.L.; Ward, J.; Balian, C.; Gilger, E.; Murray, P.; Li, Z. Using patient-reported outcomes to measure symptoms in children with advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Orellana, L.; Ullrich, C.; Cook, E.F.; Kang, T.I.; Rosenberg, A.; Geyer, R.; Feudtner, C.; Dussel, V. Symptoms and distress in children with advanced cancer: Prospective patient-reported outcomes from the PediQUEST study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekar, A.A.; Cascella, M. WHO Analgesic Ladder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554435/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Splinter, W. Novel approaches for treating pain in children. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutelman, P.R.; Chambers, C.T.; Stinson, J.N.; Parker, J.A.; Fernandez, C.V.; Witteman, H.O.; Nathan, P.C.; Barwick, M.; Campbell, F.; Jibb, L.A.; et al. Pain in children with cancer: Prevalence, characteristics, and parent management. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahed, G.; Koohi, F. Emotional and behavioral disorders in pediatric cancer patients. Iran J. Child Neurol. 2020, 14, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks-Ferguson, V. Relationships of age and gender to hope and spiritual well-being among adolescents with cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2006, 23, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin-Odanye, E.O.; Husman, A.J. Impact of stigma and stigma-focused interventions on screening and treatment outcomes in cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience 2021, 15, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.; Sawin, K.J.; Hendricks-Ferguson, V.L. Experiences of pediatric oncology patients and their parents at end of life: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 33, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E.; Abrams, A.N.; Banks, J.; Christofferson, J.; DiDonato, S.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Kabour, M.; Madan-Swain, A.; Patel, S.K.; Zadeh, S.; et al. Psychosocial assessment as a standard of care in pediatric cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, S426–S459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.E.; Vos, K.; Raybin, J.L.; Ward, J.; Balian, C.; Gilger, E.A.; Li, Z. Comparison of child self-report and parent proxy-report of symptoms: Results from a longitudinal symptom assessment study of children with advanced cancer. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 26, e12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, J.; Houtrow, A.J.; Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Council on Children with Disabilities. Pain assessment and treatment in children with significant impairment of the central nervous system. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20171002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P.S.; Nuss, S.L.; Ruccione, K.S.; Withycombe, J.S.; Jacobs, S.; DeLuca, H.; Faulkner, C.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.I.; Gross, H.E.; et al. PROMIS pediatric measures in pediatric oncology: Valid and clinically feasible indicators of patient-reported outcomes. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.B.; McFatrich, M.; Mack, J.W.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Jacobs, S.S.; Baker, J.N.; Withycombe, J.S.; Lin, L.; Mann, C.M.; Villabroza, K.R.; et al. Expanding construct validity of established and new PROMIS Pediatric measures for children and adolescents receiving cancer treatment. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Katz, E.R.; Meeske, K.; Dickinson, P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer 2002, 94, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.J.; Devine, T.D.; Dick, G.S.; Johnson, E.A.; Kilham, H.A.; Pinkerton, C.R.; Stevens, M.M.; Thaler, H.T.; Portenoy, R.K. The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: The validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7-12. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2002, 23, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, L.M.; Fahner, J.C.; Sondaal, S.F.V.; Schouten-van Meeteren, A.Y.N.; de Kruiff, C.C.; van Delden, J.J.M.; Kars, M.C. Anticipating the future of the child and family in pediatric palliative care: A qualitative study into the perspectives of parents and healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadatou, D.; Kalliani, V.; Karakosta, E.; Liakopoulou, P.; Bluebond-Langner, M. Home or hospital as the place of end-of-life care and death: A grounded theory study of parents’ decision-making. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Kang, T.I.; Mack, J.W. Racial and ethnic differences in parental decision-making roles in pediatric oncology. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Friedrich, A.; Blazin, L.J.; Baker, J.N.; Mack, J.W.; DuBois, J. Communication in pediatric oncology: A qualitative study. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20201193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick Communication Reference Guide. Available online: https://blogs.stjude.org/progress/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/04/StJude-physician-communication-guide.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Bluebond-Langner, M.; Hargrave, D.; Henderson, E.M.; Langner, R. ‘I have to live with the decisions I make’: Laying a foundation for decision making for children with life-limiting conditions and life-threatening illnesses. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.; Lam, C.G.; Cunningham, M.J.; Remke, S.; Chrastek, J.; Klick, J.; Macauley, R.; Baker, J.N. Best practices for pediatric palliative cancer care: A primer for clinical providers. J. Suppo. Oncol. 2013, 11, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.; Kirsch, R. When is enough, enough? Exploring ethical and team considerations in paediatric cardiac care dilemmas. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2022, 37, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrete, T.N.; Tariman, J.D. Pediatric palliative care: A literature review of best practices in oncology nursing education programs. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 23, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streuli, J.C.; Widger, K.; Medeiros, C.; Zuniga-Villanueva, G.; Trenholm, M. Impact of specialized pediatric palliative care programs on communication and decision-making. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, P.J.; Herbert, A.R.; Baggio, S.J.; Donovan, L.A.; McLarty, A.M.; Duffield, J.A.; Pedersen, L.C.; Duc, J.K.; Delaney, A.M.; Johnson, S.A.; et al. Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Evaluating the impact of national education in pediatric palliative care: The Quality of Care Collaborative Australia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrichsdorf, S.J.; Remke, S.; Hauser, J.; Foster, L.; Postier, A.; Kolste, A.; Wolfe, J. Development of a Pediatric Palliative Care Curriculum and Dissemination Model: Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Pediatrics. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 58, 707–720.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, M.S.; Wichman, C. Implementation of a competency-based, interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care curriculum using content and format preferred by pediatric residents. Children 2018, 5, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granek, L.; Bartels, U.; Barrera, M.; Scheinemann, K. Challenges faced by pediatric oncology fellows when patients die during their training. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, e182–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education; Board on Global Health; Institute of Medicine. Interprofessional Education for Collaboration: Learning How to Improve Health from Interprofessional Models across the Continuum of Education to Practice: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klick, J.C.; Hauer, J. Pediatric palliative care. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2010, 40, 120–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, E.R.; Frost, A.C.; Kane, H.L.; Rokoske, F.S. Barriers to accessing palliative care for pediatric patients with cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer 2018, 124, 2278–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R. How to make communication among oncologists, children with cancer, and their caregivers therapeutic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2122536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, E.D.; Levine, J.M. The day two talk: Early integration of palliative care principles in pediatric oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4068–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, E.C.; Snaman, J.M.; Baker, J.N. Pediatric palliative oncology: Bridging silos of care through an embedded model. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2740–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brock, K.E.; Allen, K.E.; Falk, E.; Velozzi-Averhoff, C.; DeGroote, N.P.; Klick, J.; Wasilewski-Masker, K. Association of a pediatric palliative oncology clinic on palliative care access, timing and location of care for children with cancer. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruera, E.; Hui, D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, L.E.; De La Cruz, M.; Wong, A.; Castro, D.; Bruera, E. Snapshot of an outpatient supportive care center at a comprehensive cancer center. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstraesser, E.; Flury, M. Care at the end of life for children with cancer. In Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Skiadaresis, J.; Alexander, S.; Wolfe, J. Differences in end-of-life communication for children with advanced cancer who were referred to a palliative care team. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilden, J. It is time to let in pediatric palliative care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, K.; Cignacco, E.; Engberg, S.; Ramelet, A.S.; von der Weid, N.; Eskola, K.; Bergstraesser, E.; on behalf of the PELICAN Consortium; Ansari, M.; Aebi, C.; et al. Patterns of paediatric end-of-life care: A chart review across different care settings in Switzerland. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Grier, H.E.; Klar, N.; Levin, S.B.; Ellenbogen, J.M.; Salem-Schatz, S.; Emanuel, E.J.; Weeks, J.C. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odejide, O.O.; Steensma, D.P. Patients with haematological malignancies should not have to choose between transfusions and hospice care. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e418–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Kato, I.; Umeda, K.; Hiramatsu, H.; Takita, J.; Adachi, S.; Tsuneto, S. Continuous deep sedation at the end of life in children with cancer: Experience at a single center in Japan. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 37, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arantzamendi, M.; Belar, A.; Payne, S.; Rijpstra, M.; Preston, N.; Menten, J.; Van der Elst, M.; Radbruch, L.; Hasselaar, J.; Centeno, C. Clinical aspects of palliative sedation in prospective studies. A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 831–844.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horridge, K.A. Advance care planning: Practicalities, legalities, complexities and controversies. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sanderson, A.; Hall, A.M.; Wolfe, J. Advance care discussions: Pediatric clinician preparedness and practices. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, S.; Fletcher, K.; Goldstein, R. The grief of parents after the death of a young child. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2019, 26, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

At diagnosis

|

During illness

|

Related to complex needs

|

| Diagnosis | Progression | End of Life | After Death Care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom management |

|

|

| |

| Management of psychological, social, spiritual needs |

|

|

|

|

| Assessment of the quality of life |

|

|

| |

| Communication |

|

|

|

|

| Family support |

|

|

|

|

| Coordination activities |

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benini, F.; Avagnina, I.; Giacomelli, L.; Papa, S.; Mercante, A.; Perilongo, G. Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology: Basic Principles. Cancers 2022, 14, 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14081972

Benini F, Avagnina I, Giacomelli L, Papa S, Mercante A, Perilongo G. Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology: Basic Principles. Cancers. 2022; 14(8):1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14081972

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenini, Franca, Irene Avagnina, Luca Giacomelli, Simonetta Papa, Anna Mercante, and Giorgio Perilongo. 2022. "Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology: Basic Principles" Cancers 14, no. 8: 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14081972

APA StyleBenini, F., Avagnina, I., Giacomelli, L., Papa, S., Mercante, A., & Perilongo, G. (2022). Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology: Basic Principles. Cancers, 14(8), 1972. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14081972