Simple Summary

Platinum-based agents are one of the most widely used chemotherapy drugs for various types of cancer. However, one of the main challenges in the application of platinum drugs is resistance, which is currently being widely investigated. Epigenetic DNA methylation-based biomarkers are promising to aid in the selection of patients, helping to foresee their platinum therapy response in advance. These biomarkers enable minimally invasive patient sample collection, short analysis, and good sensitivity. Hence, improved methodologies for the detection and quantification of DNA methylation biomarkers will facilitate their use in the choice of an optimal treatment strategy.

Abstract

Platinum-based chemotherapy is routinely used for the treatment of several cancers. Despite all the advances made in cancer research regarding this therapy and its mechanisms of action, tumor resistance remains a major concern, limiting its effectiveness. DNA methylation-based biomarkers may assist in the selection of patients that may benefit (or not) from this type of treatment and provide new targets to circumvent platinum chemoresistance, namely, through demethylating agents. We performed a systematic search of studies on biomarkers that might be predictive of platinum-based chemotherapy resistance, including in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical models and clinical studies using patient samples. DNA methylation biomarkers predictive of response to platinum remain mostly unexplored but seem promising in assisting clinicians in the generation of more personalized follow-up and treatment strategies. Improved methodologies for their detection and quantification, including non-invasively in liquid biopsies, are additional attractive features that can bring these biomarkers into clinical practice, fostering precision medicine.

1. Introduction

Platinum-based agents (cisplatin (CDDP), carboplatin, and oxaliplatin) are broadly used for the treatment of several cancer types. Notwithstanding their broad spectrum of clinical use, several concerns remain, especially the emergence of treatment resistance, which causes additional challenges. Over the last decades, epigenetic biomarkers, especially those related to DNA methylation, have increasingly shown their value as cancer biomarkers, amenable for simple, fast, and low-cost detection in a non- or minimally invasive way. These are highly versatile, with value for diagnosis, risk stratification, and prediction of response to a specific treatment, sparing patients from harmful and unnecessary side effects. However, the setup and confirmation of a reliable biomarker with a strong routine clinical application is a complex process, which takes many steps from in vitro experiments to in vivo pre-clinical model validation and patient tissue analysis, with further validation in independent (multi-institutional) cohorts to ensure the desired high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy [1,2]. Indeed, there is a plethora of studies proposing new biomarkers, but very few have made their way to clinical practice for several reasons including pre-analytical issues, cohort demographic variations, and a lack of standardized reporting, among many others [3]. In this review, we focused on epigenetic-based biomarkers, specifically DNA methylation, which might be used to predict response to platinum-based chemotherapy, emphasizing their establishment and detection methods.

1.1. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy: Brief Definition and Mechanisms of Action

Platinum anticancer drugs are routinely used for the treatment of several types of malignancies, both solid and hematolymphoid. Since the discovery of CDDP anti-tumor activity in 1969 and following its approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1978, platinum-based chemotherapy has been widely used in cancer treatment, which makes research on its mechanism of action and resistance extremely relevant for contemporary oncology [4,5]. Although CDDP remains the most commonly used platinum drug in the clinic, two analogs were also approved for tumor types: carboplatin (in 1989) and oxaliplatin (in 2002) [6,7].

Platinum-based chemotherapy has been proven to be effective to treat several types of cancers [8,9] and is widely used in the treatment of very distinct tumors, including esophageal (EC), gastric (GC), lung (LC) (small cell (SCLC) and non-small cell (NSCLC)), colorectal (CRC), and head and neck (HNC) cancers [10]. It is also used in urothelial (UC) and cervical (CC) carcinomas, as well as testicular and ovarian germ cell tumors (TGCT, OC). Platinum compounds are also used to treat other malignancies including leukemias, melanoma, neuroendocrine neoplasms, sarcomas, and tumors of neuroectodermal origin (such as neuroblastoma), demonstrating the versatility of these agents [11]. It is reasonable to theorize that such wide effectiveness in very distinct tumor types (with different biology, genomic drivers, risk factors, and molecular background) might be due to multiple pathways in which platinum-based drugs interfere.

Platinum compounds, especially CDDP, demonstrate remarkable clinical success in TGCT, enabling high cure rates (~80%) even in cases of heavily metastatic disease [12,13,14]. However, this specific type of testicular tumor shows hypersensitivity to CDDP, a fact that is tightly linked to its epigenetic and developmental biology background, and clinicians have not been able to reproduce such a success rate on somatic-type tumors of adulthood treated with the same platinum compounds [15,16,17]. This creates a need to fully understand the mechanism of action of this therapy and its mechanisms of resistance to improve patient care. In this review, we addressed the three platinum compounds more widely used in clinical practice, with a particular focus on the most widely used: CDDP.

CDDP has been used for years as a first-line treatment for several cancer types, either alone or in combination with other therapeutic options, such as radiation (to serve as a radiosensitizer) or other chemotherapeutics [18]. It is usually administered as either a neoadjuvant (for tumor shrinkage) or adjuvant (to lessen the risk of recurrence) therapy [19,20,21]. It may also be used in a palliative chemotherapy scenario, due to its cytotoxic activity, in an attempt to maintain patient quality of life [11]. The downside is that platinum agents demonstrate several critical side effects, such as nephrotoxicity and peripheral neurotoxicity, limiting the dose that might be used for patient treatment [22]. Additionally, cancer survivors previously treated with platinum disclose traceable levels of CDDP in urine and plasma many years after treatment, which is a major concern that may cause long-term side effects, triggering a decline in quality of life and, ultimately, resulting in death [23,24,25]. The current precision medicine paradigm is no longer compliant with sustaining such side effects either in a short and/or long term, and all efforts must be placed in improving risk stratification of patients with appropriate biomarkers to spare patients from futile, unnecessary treatments and their side effects.

Chemically, CDDP or cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) is formed by one platinum atom bound to two chloride atoms and two amide groups [26]. CDDP is known to cross the cell membrane by passive diffusion or through transmembrane transporters, of which the most studied are the copper transporters CTR1 and CTR2 [27,28]. The cytosol favors the aquation process of CDDP due to chloride concentration entailing CDDP activation [29]. Once inside the cell, CDDP binds strongly to the N7 reactive center of purine residues, causing DNA damage by creating adducts, blocking cell division, and resulting in apoptotic cell death [8,30]. CDDP, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin may cause different DNA adducts [30,31,32]; the fundamental cellular processes related to the CDDP mechanism are not fully understood and are subject to continuous study [33,34,35].

Carboplatin, also called cis-diamino-(1,1-cyclobutandicarboxylate) platinum (II), discloses a more favorable safety profile when compared to CDDP [36]. The downside is that carboplatin is much less potent, and, usually, a substantially higher clinical dose is required to match CDDP efficacy [37]. The mechanism of action of carboplatin is very similar to CDDP; previous works have demonstrated that CDDP-resistant tumor cell lines are cross-resistant to carboplatin as well [37].

Oxaliplatin has a 1,2-diaminocyclohexane carrier ligand [38]. Generally, oxaliplatin is more effective than CDDP in vitro [39]. However, single-agent oxaliplatin has low activity in many tumors clinically; thus, it is often combined with other drugs such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [40,41]. Currently, it is mostly used in the treatment of advanced CRC [42]. Unlike CDDP and carboplatin, oxaliplatin reacts rapidly in plasma, undergoing a process of transformation into reactive compounds due to the displacement of the oxalate group [31].

1.2. A Brief Introduction to DNA Methylation

The radical difference between genetic and epigenetic changes is that genetic lesions are irreversible whereas epigenetic lesions are potentially reversible as they are associated with gain or loss of DNA methylation or other modifications of chromatin, thus enabling therapeutic intervention [43,44]. Epigenetic mutations, also called epimutations, are heritable; they may be constitutional and derived from a germline, thus expected to be found in all of the tissues of an individual, or they may be somatic, eventually restricted to a specific somatic tissue [45]. Epigenetic aberrations may consist of abnormal patterns of DNA methylation, disrupted patterns of histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs), altered expression of small non-coding RNAs, and alterations in chromatin composition and/or organization [46]. Histone modification and DNA methylation specifically regulate gene expression at the transcriptional level, preceding morphological changes associated with neoplastic transformation and even genetic alterations [47].

1.3. DNA Methylation Regulates Transcription and Affects Protein Levels

DNA methylation mostly affects CpG dinucleotides and is involved in tumorigenesis through three main mechanisms: locus-specific (e.g., tumor suppressor genes (TSG)) hypermethylation [48], global hypomethylation of the cancer genome [49], or direct mutagenesis of 5mC sequences [50,51]. It is noteworthy that all three routes occur simultaneously, indicating the importance of methylation as an epigenetic driver in cancer development. Hypermethylation negatively impacts transcription, reducing levels of the proteins responsible for processes such as DNA damage repair, creating a fundamental replication advantage over normal cells [52]. It was demonstrated that DNA methylation alterations result from the altered expression of methyltransferases [53]. Since these enzymes are responsible for the transfer of a methyl group to DNA, their up/downregulation leads to DNA hyper/hypomethylation, thus impairing normal epigenetic regulation and enabling malignant transformation and progression together with the increase in chemoresistance [54]. Importantly, due to their significant role in the epigenome regulation, methyltransferases could serve as a suitable therapeutic target in cancer treatment [55].

1.4. Epigenetic-Based Cancer Biomarkers

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Dictionary of Cancer Terms, a cancer biomarker is a biological molecule that is found in blood or other body fluids or tissues, which indicates an abnormal, cancer-related process or condition [56]. Biomarkers vary depending on their objective (risk assessment, diagnosis, prognosis, or prediction of response to therapy), and herein we focus on the predictive type of biomarkers, which forecast the response to a specific treatment [57]. Ideally, a biomarker should have perfect (100%) specificity and sensitivity [57,58]. We reviewed available data on cancer cell lines and patient tissues because these are critical for the development of reliable biomarkers’ detection and establishment, including those based on the hypermethylation of gene promoters [59,60]. Recently, many studies focused on the need to identify and select reliable biomarkers for all kinds of cancer treatment. Sample (blood, urine, stool) collection is minimally or non-invasive and may thus be performed more frequently, allowing for easier and earlier diagnosis, disease monitoring, and easy storage [61]. Furthermore, it may assist clinicians in the decision of prescribing neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment [59]. In this context, personalized medicine has become a priority. It is widely acknowledged that there is no universal treatment for cancer and that some patients are resistant to specific types of treatment. A perfect treatment strategy should target cancer cells in all the pathways that are crucial for their survival. Since epi-genetic aberrations may, at the least partially, contribute to cancer resistance to therapy and relapse, epigenetic modulation, such as DNA demethylating agents, may prove useful [62,63]. In this scenario, epigenetic-based biomarkers become relevant to determine whether a patient might benefit from a specific chemotherapy regimen, including those that are platinum based.

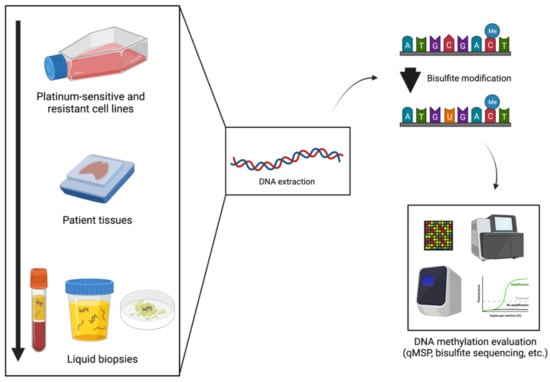

Among cancer-related epigenetic alterations, we focused our literature search on DNA methylation as a biomarker for predicting patient response to platinum-based chemotherapy (Figure 1). Indeed, DNA methylation itself is advantageous compared to other epigenetic biomarkers not only because it can be detected in non-invasively collected body fluids but also because it is representative of tumor heterogeneity. Whereas primary tumor and metastatic deposits’ tissue samples are highly heterogeneous, having several tumor cell clones, which may be missed by needle biopsy sampling, circulating tumor cells or nucleic acids are representative of the tumor bulk, either primary or metastatic [63,64]. Additionally, either in tissue or liquid biopsy specimens, DNA is much more stable and resistant to degradation (by formalin fixation, freeze, and thawing procedures) than RNA [57,65,66]. Furthermore, data obtained from the assessment of DNA methylation may be compared to absolute reference points (fully methylated/unmethylated DNA) allowing for quantification [65].

Figure 1.

Platinum- resistance DNA methylation biomarkers’ examination process. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 1 February 2022).

Currently, there is a large number of methods to detect DNA methylation, either target-based (e.g., methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (MSP), bisulfite sequencing, pyrosequencing methylation-specific restriction endonucleases, etc.) or genome wide-based (e.g., 450K or 850K array) and a vast amount of data are available publicly, enabling comparisons [67]. Finally, improvements in technology are under development to facilitate the detection of DNA methylation biomarkers in an absolute way without the need for pre-amplification reactions (e.g., droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)) [68,69].

Although such biomarkers seem auspicious due to their feasibility, they are not widely used in practice because of their limited sensitivity compared to the available standard-of-care tools. The particular reason for this circumstance is that often the detection of a single biomarker (e.g., promoter hypermethylation of a specific gene) is not sufficient to obtain a reliable conclusion and gene panels are required to overcome this limitation. Furthermore, for validation purposes, promoter methylation status must be confirmed using multiple methods and in several cohorts with distinct demographic features before. Additionally, other environmental conditions might impact gene methylation acting as confounders in cancer biomarker studies [67,70]. Additional problems are related to biomarker results’ interpretation and reporting, including normalization (appropriate normalizers, method of relative quantification), sample and DNA input conditions (which may be prohibitive in specific clinical scenarios), cost-related issues, etc.

To set up a reliable biomarker predictive of response to chemotherapy, one needs to identify relevant genes by compiling and testing training and validation cohorts and comparing DNA methylation status among specific cohorts of patients, specifically, in this setting, patients who responded (either completely or partially) to treatment and those who did not respond and endured a poor outcome [57,67,71]. Additionally, adjusting for demographic and clinicopathologic factors (age, gender, grade, stage, baseline characteristics of patients, etc.) is very relevant since DNA methylation biomarkers may lose their predictive value after adjustment in multivariable models. Moreover, cancer cell line testing is important to illuminate how chemotherapy-sensitive and -resistant cells react to treatment, evaluating whether the methylation profile changes over time and if the use of a demethylating agent sensitizes resistant cells [72]. For that purpose, the collection of patient tissue samples (for instance, biopsies, FFPE tissue samples, frozen samples, etc.), the extraction of DNA (assuring the best possible quality), and performing bisulfite treatment (or variations, such as with the use of methylation-sensitive endonucleases) followed by targeted MSP-based methods are required (Figure 1). Then, if sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and overall accuracy reach high levels of performance, a biomarker is a candidate for further testing in body fluids to determine whether it will constitute a reliable biomarker for clinical use [65].

2. Research Methodology

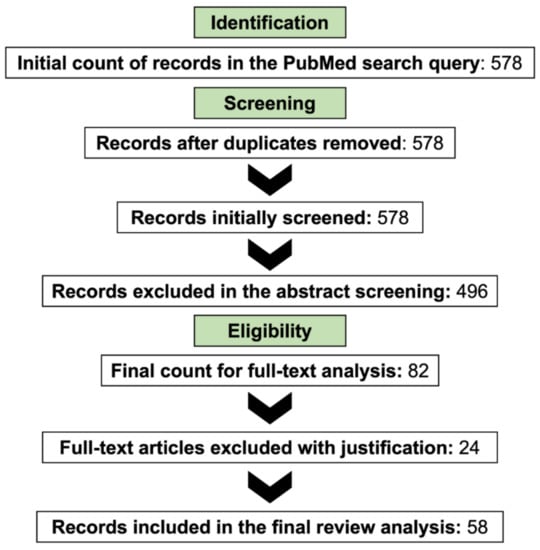

For the purposes of this review, a PubMed database search was conducted with the query (cisplatin OR carboplatin OR oxaliplatin) AND (DNA methylation OR epigenetics) AND (resistance OR chemoresistance). The search only considered original records published in English (i.e., reviews were excluded) and no restricted time interval was considered. Initially, the articles were chosen through comprehensive abstract analysis, and the final count was reached after a critical, full-text read of those that conveyed significant information for the topic. For this review, only studies analyzing the role of DNA methylation in platinum-based chemotherapy resistance using human cell lines or patient samples were considered. Figure 2 depicts the flow diagram representing the methodology used to reach the final set of selected sources of information. The information collected is summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, which depict epigenetically regulated genes associated with platinum-based chemotherapy resistance in cell lines (Table 1) or patient tissues (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The research methodology employed for this review.

Table 1.

Promising DNA methylation markers predictive of resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy (mechanistic studies with cell lines). Genes related with the three most common platinum drug resistance pathways are indicated as [T], genes encoding proteins’ transporters, related with cellular uptake of platinum drugs; [R], genes encoding proteins responsible for DNA damage repair; or [A], genes encoding proteins related with the induction of apoptotic cell death.

Table 2.

Promising DNA methylation markers predictive of resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy (studies with patient samples). Genes related with the three most common platinum drug resistance pathways are indicated as [T], genes encoding proteins’ transporters, related with cellular uptake of platinum drugs; [R], genes encoding proteins responsible for DNA damage repair; or [A], genes encoding proteins related with induction of apoptotic cell death.

3. Discussion

DNA Methylation and Platinum Resistance

Resistance to platinum treatment can be divided into two main types: intrinsic and acquired. Many patients that initially are sensitive to the treatment often develop resistance to it during their treatment course, causing relapse and reducing its overall clinical efficacy [29]. The development of new CDDP analogs, with fewer side effects, also aimed to tackle resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy, a goal which was not fully achieved and that also met with decreased effectiveness.

Changes in the epigenetic landscape, a cancer hallmark [129], appear to be nonrandom and are associated with the acquisition of chemoresistance to platinum in various types of cancers [130,131]. Indeed, platinum-based chemotherapy seems to induce changes in DNA methylation patterns [33,77,96,101,132]. This epigenetic mechanism plays a substantial role in the platinum resistance mechanism, affecting the transcription and translation of genes involved in reduced platinum influx to the cell or increased export (e.g., ABCB1), increased DNA damage repair routes (e.g., BRCA1, ERCC1, MLH1, hMSH2), inactivation of apoptosis pathways (e.g., Casp8AP2, GULP1, p73, RIP3), or increased platinum detoxification (e.g., MT1E) (Table 1 and Table 2). DNA damage repair pathways, for instance, have been proven to be of critical importance in the process of resistance to platinum compounds due to the DNA adducts these create [8,26,29,62,133]. The mismatch repair pathway (MMR) is a vital tool to keep genome stability, and a deficiency in this system has been shown to cause CDDP resistance in cells, associated with poor prognosis in some tumors [26,133]. Several previous studies have shown that promoter hypermethylation of genes involved in this pathway, such as MLH1 and hMSH2, is associated with the acquisition of resistance to platinum therapy [72,92,105,110,121,124]. The NRF2/KEAP1 pathway plays a key role in the chemoresistance process of different tumor types and is capable of inhibiting apoptosis, promoting cell proliferation, and chemoresistance [134]. This pathway has already shown to be regulated by epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation [135]. Additionally, genes such as ERα and ABC transporters, proven to be involved in the chemoresistance process, are regulated by the NRF2/KEAP1 pathway [136].

Our review of the literature disclosed several publications on the relevance of DNA methylation-based biomarkers for the prediction of response to platinum therapy, notwithstanding their heterogeneity concerning methodological settings (cell lines vs. tumor tissues). However, no such biomarker has been approved so far [57]. There are several critical steps in the validation of biomarkers as well as several hurdles that make the process of approval very strict, complex, time-consuming, and expensive, justifying why so very few of these markers make it all the way to clinical practice [2,57,65,71,137]. All these limitations make DNA methylation predictive biomarkers for platinum-based chemotherapy still relatively unexplored. One of the main problems observed in this type of study is the size of the validation cohort. If the cohort of patients treated with platinum compounds is not large enough, reliable conclusions about the predictive value of biomarkers cannot be drawn [74,92,99,105]. Thus, sample size estimation is mandatory to assure that the study cohort(s) enable the identification of significant differences between responders and non-responders if they exist. Additionally, multiple clinical variables must be considered, and the results should be adjusted/stratified according to these parameters, such as tumor type, stage, the platinum compound used for treatment, and treatment response, among others, as these are highly relevant clinical factors that may significantly influence methylation levels as well as the likelihood of response to therapy [57,71].

Another relevant issue is the estimation of tumor cell density in tissue samples tested. For example, the percentage of tumor in tissue sections chosen for DNA purification varies widely among published reports, from >30% of tumor cells [117] to >70% [82,125] or even >90% [98,122]. This variability is very likely to influence the determination of methylation levels (even considering that normalization for input has been made), jeopardizing the comparison of results and the reproducibility of experiments, undermining the possibility of biomarker validation [138].

An important and very common limitation in the publications assessed is the lack of information in clinical studies concerning biomarker performance parameters, such as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, etc. [81,92,123]. These parameters are critical to evaluating the potential of the new DNA methylation biomarkers and comparing them with conventional methods or other markers that are routinely used in clinical care at present. Considering published data reviewed and depicted in Table 2, reported sensitivity or specificity values are modest (e.g., 67% [92] or 45% [81] sensitivity), probably owing to the very small size of initial tissue biopsies, which may not provide enough DNA for the experiments using several replicates, or contamination of purified DNA with tissue residues such as proteins, complicating the determination of correlation between gene methylation and expression [57,65,139,140]. To overcome this problem, optimal sample processing should be ensured and cohort size should be increased to account for variations in DNA concentration and purity among samples, enabling a more robust analysis of results [65].

Interestingly, differences in tissue condition regarding treatment are also apparent among the studies on methylation analysis. Whereas, in most studies, the tumor tissue analyzed for DNA methylation was collected after platinum treatment [108,109,117], in some assessed tumor tissue samples collected from untreated patients, primary cell cultures were established and were exposed to platinum prior to methylation analyses [88,98]. Results from these two strategies must be compared with caution because the presence or absence of the tumor microenvironment and altered cell communication derived from culture conditions is likely to entail the activation of different pathways [141].

Most clinical studies (i.e., those based on patient cohorts) performed DNA methylation analysis in tissues, either fresh, frozen, or formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin. Indeed, very few have used liquid biopsies [75,103], which seem advantageous considering they are easier, less invasive, faster, and more comfortable to obtain compared with conventional tissue biopsies. Importantly, liquid biopsies allow for real-time monitoring, as blood or urine may be drawn periodically and biomarkers assessed over shorter or longer periods of time [137,142,143].

In addition to in vitro and clinical studies, in vivo animal models are very useful in cancer research as they more closely replicate the complexity and heterogeneity of cancer tissues compared to in vitro cell line studies [144]. Nonetheless, they are much more expensive and represent a superior work burden and some of these models may not very precisely mimic the human tumor microenvironment [145]. From our search, very few studies on DNA methylation biomarkers or therapeutic targets of platinum-based chemotherapy have used animal models and the ones that did mostly used those in in vivo assays to complement the in vitro cell studies [100,108,115].

Notwithstanding the hypothesis that DNA methylation biomarkers might help to predict a response to platinum-based chemotherapy, they may also represent important therapeutic targets that might help sensitize tumor cells to platinum compounds [72,74,80,86,95,99,107]. For instance, a previous study showed that the impairment of ABCB1 expression due to promoter hypermethylation caused a reduction in the ABCB1 transporter and lessened CDDP resistance [95]. Another study showed that promoter methylation levels of BRCA1, a key gene involved in DNA repair, were higher in CDDP-resistant ovarian cancer cell lines and that exposure to a demethylating agent sensitized those cells to platinum treatment [107]. Thus, if further demonstrated in clinical studies, DNA methylation patterns might allow for the improvement of therapeutic strategies [57,65,71].

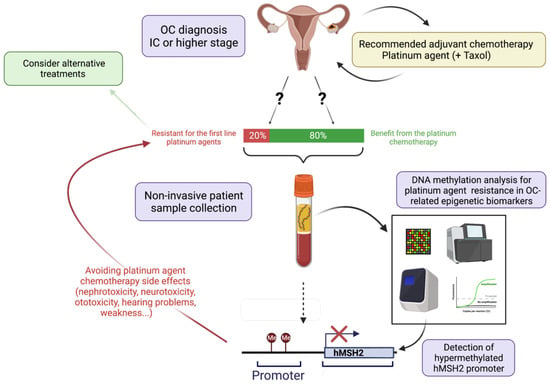

Figure 3 illustrates the ideal process of how a biomarker of platinum-based agent resistance (in this case, hMSH2 promoter hypermethylation) could be validated and confirmed as a predictive biomarker, assisting in the therapeutic decision for OC patients, improving survival and quality of life.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of pipeline for validation of DNA methylation-based biomarker to predict resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy in ovarian cancer (OC) patients. After a clinical diagnosis of OC (top of the picture), if the disease was staged as IC or higher, the recommended treatment is adjuvant chemotherapy with a platinum agent (CDDP, carboplatin, or oxaliplatin), eventually in combination with Taxol. However, there is a 20% probability that the patient will be resistant to platinum agents, which complicates the choice of treatment [66]. To select the best treatment method, biomarker validation could be performed. This follows with non-invasive patient sample collection (for instance, blood plasma), which can be used for circulating tumor DNA methylation analysis, focusing on platinum agent resistance. In this case, gene promoter hypermethylation indicating platinum resistance in OC was detected (e.g., hMSH2) [124], indicating that the patient will likely endure platinum resistance. Thus, not only may the side effects of ineffective treatment [22] be avoided but alternative treatments, eventually including epi-drugs, should be considered. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 1 February 2022).

Epi-drugs, which may be inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases, histone deacetylases, histone acetyltransferases, histone methyltransferases, or histone demethylases, may play an important role in cancer treatment by enhancing the effects of combinational therapy with platinum-based compounds as sensitizers [146,147]. This was shown in several clinical trials [73,148,149] and opens the way for a wider use of predictive DNA methylation-based biomarkers in tumors candidating for treatment with platinum compounds. Although holding substantial potential for the enactment of precision medicine, more robust validation studies are required to provide definitive evidence.

4. Conclusions

Presently, cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide and its incidence and mortality are increasing. Thus, in parallel with the implementation of preventive and early diagnosis measures, the development of effective and patient-specific therapeutic strategies is required to tackle this growing public health problem. Platinum-based chemotherapy, in use for more than 40 years, remains the first-line treatment for many types of cancer; resistance to this therapy is a major concern. Importantly, epigenetic dysregulation, specifically aberrant DNA methylation, plays an important role in the resistance process. Thus, biomarkers based on DNA methylation might enable the identification of those tumors more prone to demonstrate or acquire resistance to platinum compounds as well as constituting therapeutic targets enabling the sensitization of tumors. Thus, many studies have been undertaken to unveil and validate candidate biomarkers. Our review disclosed several mechanistic studies with cell lines and animal models, as well as some clinical studies, using patient samples, which identified some promising DNA methylation biomarkers predictive of response/resistance to platinum treatment. However, none of these biomarkers has been validated yet since most clinical studies analyzed small cohorts and the heterogeneity of patients, samples, and analytical methods precludes a meaningful and decisive conclusion. Hence, there is an urgent need to set up clinical validation studies, with adequate statistical power to enable the identification of the added value of those epigenetic biomarkers. This requires a joint effort from basic scientists and clinicians, departing from the more robust pre-clinical and clinical data available and bridging the gap that will lead to biomarker-assisted therapeutic decisions for patients who are candidates for platinum-based chemotherapy.

Author Contributions

N.T.T. and S.G. drafted the manuscript and figures. J.L., C.J. and R.H. supervised the work and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Research Center of the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto (CI-IPOP–FBGEBC-27). NTT holds a contract funded by Programa Operacional Regional do Norte and is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund under the project “The Porto Comprehensive Cancer Center” with the reference NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-072678 (Porto.CCC, Contract RNCCCP.CCC-CI-IPOP-LAB3).

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during the current review are available in the PubMed repository, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 1 February 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lobo, J.; Gillis, A.J.M.; van den Berg, A.; Dorssers, L.C.J.; Belge, G.; Dieckmann, K.P.; Roest, H.P.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; Gietema, J.; Hamilton, R.J.; et al. Identification and Validation Model for Informative Liquid Biopsy-Based microRNA Biomarkers: Insights from Germ Cell Tumor in Vitro, in Vivo and Patient-Derived Data. Cells 2019, 8, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; Bathe, O.F. Response biomarkers: Re-envisioning the approach to tailoring drug therapy for cancer. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariat, S.F.; Lotan, Y.; Vickers, A.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Schmitz-Drager, B.J.; Goebell, P.J.; Malats, N. Statistical consideration for clinical biomarker research in bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2010, 28, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, B.; Vancamp, L.; Trosko, J.E.; Mansour, V.H. Platinum Compounds: A New Class of Potent Antitumour Agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amable, L. Cisplatin resistance and opportunities for precision medicine. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 106, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrap, K.R. Preclinical studies identifying carboplatin as a viable cisplatin alternative. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1985, 12 (Suppl. A), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machover, D.; Diaz-Rubio, E.; de Gramont, A.; Schilf, A.; Gastiaburu, J.J.; Brienza, S.; Itzhaki, M.; Metzger, G.; N’Daw, D.; Vignoud, J.; et al. Two consecutive phase II studies of oxaliplatin (L-OHP) for treatment of patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma who were resistant to previous treatment with fluoropyrimidines. Ann. Oncol. 1996, 7, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharm. 2014, 740, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desoize, B.; Madoulet, C. Particular aspects of platinum compounds used at present in cancer treatment. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2002, 42, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Kumar, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy of Human Cancers. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2019, 11, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron, M.A.; Oing, C.; Bremmer, F.; Ströbel, P.; Murray, M.J.; Coleman, N.; Amatruda, J.F.; Honecker, F.; Bokemeyer, C.; Albers, P.; et al. The developmental origin of cancers defines basic principles of cisplatin resistance. Cancer Lett. 2021, 519, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Fazal, Z.; Corbet, A.K.; Bikorimana, E.; Rodriguez, J.C.; Khan, E.M.; Shahid, K.; Freemantle, S.J.; Spinella, M.J. Epigenetic Remodeling through Downregulation of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Mediates Chemotherapy Resistance in Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. Cancers 2019, 11, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, P.; Albrecht, W.; Algaba, F.; Bokemeyer, C.; Cohn-Cedermark, G.; Fizazi, K.; Horwich, A.; Laguna, M.P.; Nicolai, N.; Oldenburg, J.; et al. Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2015 Update. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, J.; Constancio, V.; Guimaraes-Teixeira, C.; Leite-Silva, P.; Miranda-Goncalves, V.; Sequeira, J.P.; Pistoni, L.; Guimaraes, R.; Cantante, M.; Braga, I.; et al. Promoter methylation of DNA homologous recombination genes is predictive of the responsiveness to PARP inhibitor treatment in testicular germ cell tumors. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 846–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, J.; Gillis, A.J.M.; Jeronimo, C.; Henrique, R.; Looijenga, L.H.J. Human Germ Cell Tumors are Developmental Cancers: Impact of Epigenetics on Pathobiology and Clinic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalavska, K.; Conteduca, V.; De Giorgi, U.; Mego, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance in Testicular Germ Cell Tumors-clinical Implications. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, J.; Jeronimo, C.; Henrique, R. Morphological and molecular heterogeneity in testicular germ cell tumors: Implications for dedicated investigations. Virchows Arch. 2021, 479, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfenstein, S.; Riesterer, O.; Meier, U.R.; Papachristofilou, A.; Kasenda, B.; Pless, M.; Rothschild, S.I. 3-weekly or weekly cisplatin concurrently with radiotherapy for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck—A multicentre, retrospective analysis. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, R.; Bergman, B.; Dunant, A.; Le Chevalier, T.; Pignon, J.P.; Vansteenkiste, J.; International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Collaborative Group. Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gong, Y.-B.; Xu, H.-M. Neoadjuvant therapy strategies for advanced gastric cancer: Current innovations and future challenges. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2020, 6, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Sinha, R.J.; Bhaskar, V.; Aeron, R.; Sharma, A.; Singh, V. Role of gemcitabine and cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in muscle invasive bladder cancer: Experience over the last decade. Asian J. Urol. 2019, 6, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabik, C.A.; Dolan, M.E. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2007, 33, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovanec, M.; Abu Zaid, M.; Hanna, N.; El-Kouri, N.; Einhorn, L.H.; Albany, C. Long-term toxicity of cisplatin in germ-cell tumor survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2670–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santabarbara, G.; Maione, P.; Rossi, A.; Gridelli, C. Pharmacotherapeutic options for treating adverse effects of Cisplatin chemotherapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016, 17, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellesnes, R.; Myklebust, T.Å.; Fosså, S.D.; Bremnes, R.M.; Karlsdottir, Á.; Kvammen, Ø.; Tandstad, T.; Wilsgaard, T.; Negaard, H.F.S.; Haugnes, H.S. Testicular Cancer in the Cisplatin Era: Causes of Death and Mortality Rates in a Population-Based Cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3561–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.R.R.; Silva, M.M.; Quinet, A.; Cabral-Neto, J.B.; Menck, C.F.M. DNA repair pathways and cisplatin resistance: An intimate relationship. Clinics 2018, 73, e478s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, B.G.; Larson, C.A.; Safaei, R.; Howell, S.B. Copper Transporter 2 Regulates the Cellular Accumulation and Cytotoxicity of Cisplatin and Carboplatin. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4312–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, S.; Lee, J.; Thiele, D.J.; Herskowitz, I. Uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin mediated by the copper transporter Ctr1 in yeast and mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14298–14302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Krishnamurthy, S. Cellular Responses to Cisplatin-Induced DNA Damage. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 2010, 201367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimit, A.; Adebali, O.; Sancar, A.; Jiang, Y. Differential damage and repair of DNA-adducts induced by anti-cancer drug cisplatin across mouse organs. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faivre, S.; Chan, D.; Salinas, R.; Woynarowska, B.; Woynarowski, J.M. DNA strand breaks and apoptosis induced by oxaliplatin in cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 66, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, M.A.; Schwartz, A.; Rahmouni, A.R.; Leng, M. Interstrand cross-links are preferentially formed at the d(GC) sites in the reaction between cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) and DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 1982–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Cui, J.; Wen, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Cisplatin induces HepG2 cell cycle arrest through targeting specific long noncoding RNAs and the p53 signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 4605–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Ju, J.F.; Danenberg, K.D.; Danenberg, P.V. Inhibition of pre-mRNA splicing by cisplatin and platinum analogs. Int. J. Oncol. 2003, 23, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velma, V.; Dasari, S.R.; Tchounwou, P.B. Low Doses of Cisplatin Induce Gene Alterations, Cell Cycle Arrest, and Apoptosis in Human Promyelocytic Leukemia Cells. Biomark. Insights 2016, 11, BMI.S39445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooriyaarachchi, M.; Narendran, A.; Gailer, J. Comparative hydrolysis and plasma protein binding of cis-platin and carboplatin in human plasma in vitro. Metallomics 2010, 3, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, R.S.; Adjei, A.A. Review of the Comparative Pharmacology and Clinical Activity of Cisplatin and Carboplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyonari, S.; Iimori, M.; Matsuoka, K.; Watanabe, S.; Morikawa-Ichinose, T.; Miura, D.; Niimi, S.; Saeki, H.; Tokunaga, E.; Oki, E.; et al. The 1,2-Diaminocyclohexane Carrier Ligand in Oxaliplatin Induces p53-Dependent Transcriptional Repression of Factors Involved in Thymidylate Biosynthesis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 2332–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alian, O.M.; Azmi, A.S.; Mohammad, R.M. Network insights on oxaliplatin anti-cancer mechanisms. Clin. Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltz, L.B.; Clarke, S.; Díaz-Rubio, E.; Scheithauer, W.; Figer, A.; Wong, R.; Koski, S.; Lichinitser, M.; Yang, T.-S.; Rivera, F.; et al. Bevacizumab in Combination With Oxaliplatin-Based Chemotherapy As First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2013–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.; Mushin, M.; Kirkpatrick, P. Oxaliplatin. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comella, P.; Casaretti, R.; Sandomenico, C.; Avallone, A.; Franco, L. Role of oxaliplatin in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Clin. Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Rossi, A.; Garcia-Manero, G. Epigenetic therapy of leukemia: An update. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yu, D.-H.; Waterland, R.A.; Zhang, P.; Schady, D.; Chen, M.-H.; Guan, Y.; Gadkari, M.; Shen, L. Targeted p16Ink4a epimutation causes tumorigenesis and reduces survival in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3708–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.L.; Dobbins, T.; Lindor, N.M.; Rapkins, R.W.; Hitchins, M.P. Identification of constitutional MLH1 epimutations and promoter variants in colorectal cancer patients from the Colon Cancer Family Registry. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetic Determinants of Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a019505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Shin, W.; Lee, J.; Do, J. CpG and Non-CpG Methylation in Epigenetic Gene Regulation and Brain Function. Genes 2017, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S.; Fearon, E.; Vogelstein, B.; De Bustros, A.; Sharkis, S.; Burke, P.; Staal, S.; Nelkin, B. Hypermethylation of the 5′ region of the calcitonin gene is a property of human lymphoid and acute myeloid malignancies. Blood 1987, 70, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudet, F.; Hodgson, J.G.; Eden, A.; Jackson-Grusby, L.; Dausman, J.; Gray, J.W.; Leonhardt, H.; Jaenisch, R. Induction of Tumors in Mice by Genomic Hypomethylation. Science 2003, 300, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, M.J.; Wang, L. Arsenic alters cytosine methylation patterns of the promoter of the tumor suppressor gene p53 in human lung cells: A model for a mechanism of carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 1997, 386, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.H.; Kuo, K.C.; Gehrke, C.W.; Huang, L.-H.; Ehrlich, M. Heat- and alkali-induced deamination of 5-methylcytosine and cytosine residues in DNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Struct. Expr. 1982, 697, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuebel, K.E.; Chen, W.; Cope, L.; Glöckner, S.C.; Suzuki, H.; Yi, J.-M.; Chan, T.A.; Neste, L.V.; Criekinge, W.V.; Bosch, S.v.d.; et al. Comparing the DNA Hypermethylome with Gene Mutations in Human Colorectal Cancer. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3, e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Wu, C.; Cui, W.; Wang, L. DNA Methyltransferases in Cancer: Biology, Paradox, Aberrations, and Targeted Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulanovskaya, O.A.; Zuhl, A.M.; Cravatt, B.F. NNMT promotes epigenetic remodeling in cancer by creating a metabolic methylation sink. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, R.; Pozzi, V.; Sartini, D.; Salvolini, E.; Brisigotti, V.; Molinelli, E.; Campanati, A.; Offidani, A.; Emanuelli, M. Beyond Nicotinamide Metabolism: Potential Role of Nicotinamide N-Methyltransferase as a Biomarker in Skin Cancers. Cancers 2021, 13, 4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute, N.C. Definition of Biomarker. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/biomarker (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Mikeska, T.; Craig, J. DNA Methylation Biomarkers: Cancer and Beyond. Genes 2014, 5, 821–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wians, F.H. Clinical Laboratory Tests: Which, Why, and What Do The Results Mean? Lab. Med. 2009, 40, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppedè, F. Genetic and epigenetic biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.N.; Belli, A.; Di Pietro, V. Small Non-coding RNAs: New Class of Biomarkers and Potential Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talens, R.P.; Boomsma, D.I.; Tobi, E.W.; Kremer, D.; Jukema, J.W.; Willemsen, G.; Putter, H.; Slagboom, P.E.; Heijmans, B.T. Variation, patterns, and temporal stability of DNA methylation: Considerations for epigenetic epidemiology. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 3135–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.-W.; Pouliot, L.M.; Hall, M.D.; Gottesman, M.M. Cisplatin Resistance: A Cellular Self-Defense Mechanism Resulting from Multiple Epigenetic and Genetic Changes. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Peng, Y.; Gao, A.; Du, C.; Herman, J.G. Epigenetic heterogeneity in cancer. Biomark. Res. 2019, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Kit, A.; Nielsen, H.M.; Tost, J. DNA methylation based biomarkers: Practical considerations and applications. Biochimie 2012, 94, 2314–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonito, N.A.; Borley, J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.S.; Ghaem-Maghami, S.; Brown, R. Epigenetic Regulation of the Homeobox Gene MSX1 Associates with Platinum-Resistant Disease in High-Grade Serous Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdyukov, S.; Bullock, M. DNA Methylation Analysis: Choosing the Right Method. Biology 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; O’Rourke, D.; Sanchez-Garcia, J.F.; Cai, T.; Scheuenpflug, J.; Feng, Z. Development of a liquid biopsy based purely quantitative digital droplet PCR assay for detection of MLH1 promoter methylation in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, J.H.; Huibers, M.M.H.; Van Es, R.J.J.; De Bree, R.; Willems, S.M. Droplet digital PCR for detection and quantification of circulating tumor DNA in plasma of head and neck cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, F.; Ghai, M.; Maharaj, L. The effects of DNA methylation on human psychology. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 346, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C. Epigenetic biomarker development. Epigenomics 2009, 1, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, G. In vitro study of human mutL homolog 1 hypermethylation in inducing drug resistance of esophageal carcinoma. Irish J. Med. Sci. 2017, 186, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tada, Y.; Yokomizo, A.; Shiota, M.; Tsunoda, T.; Plass, C.; Naito, S. Aberrant DNA methylation of T-cell leukemia, homeobox 3 modulates cisplatin sensitivity in bladder cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 39, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xylinas, E.; Hassler, M.; Zhuang, D.; Krzywinski, M.; Erdem, Z.; Robinson, B.; Elemento, O.; Clozel, T.; Shariat, S. An Epigenomic Approach to Improving Response to Neoadjuvant Cisplatin Chemotherapy in Bladder Cancer. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Guida, E.; Inokawa, Y.; Goldberg, R.; Reis, L.O.; Ooki, A.; Pilli, M.; Sadhukhan, P.; Woo, J.; Choi, W.; et al. GULP1 regulates the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling axis in urothelial carcinoma. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaba0443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Lee, K.D.; Pai, M.Y.; Chu, P.Y.; Hsu, C.C.; Chiu, C.C.; Chen, L.T.; Chang, J.Y.; Hsiao, S.H.; Leu, Y.W. Changes in DNA methylation are associated with the development of drug resistance in cervical cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2015, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosof, L.; Yerram, S.; Armstrong, T.; Chu, N.; Danilova, L.; Yanagisawa, B.; Hidalgo, M.; Azad, N.; Herman, J.G. GPX3 promoter methylation predicts platinum sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, B.; Lu, R.; Lou, W.; Bao, Y.; Qiao, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, K.; Chen, J.; Bao, D.; Ye, M.; et al. KIF18b-dependent hypomethylation of PARPBP gene promoter enhances oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 407, 112827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, R.; Zheng, S.; Linghu, E.; Herman, J.G.; Guo, M. Methylation of SLFN11 is a marker of poor prognosis and cisplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-P.; Li, L.; Yan, J.; Hou, X.-X.; Jia, Y.-X.; Chang, Z.-W.; Guan, X.-Y.; Qin, Y.-R. Down-Regulation of CIDEA Promoted Tumor Growth and Contributed to Cisplatin Resistance by Regulating the JNK-p21/Bad Signaling Pathways in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabu, J.; Yamashita, S.; Takeshima, H.; Kishino, T.; Takahashi, T.; Oda, I.; Koyanagi, K.; Igaki, H.; Tachimori, Y.; Daiko, H.; et al. FGF5 methylation is a sensitivity marker of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to definitive chemoradiotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurimoto, K.; Hayashi, M.; Guerrero-Preston, R.; Koike, M.; Kanda, M.; Hirabayashi, S.; Tanabe, H.; Takano, N.; Iwata, N.; Niwa, Y.; et al. PAX5 gene as a novel methylation marker that predicts both clinical outcome and cisplatin sensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Zouridis, H.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, L.L.; Tan, I.B.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Ooi, C.H.; Lee, J.; Qin, L.; Wu, J.; et al. Integrated epigenomics identifies BMP4 as a modulator of cisplatin sensitivity in gastric cancer. Gut 2013, 62, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, O.; Ando, T.; Ohmiya, N.; Ishiguro, K.; Watanabe, O.; Miyahara, R.; Hibi, Y.; Nagai, T.; Yamada, K.; Goto, H. Alteration of gene expression and DNA methylation in drug-resistant gastric cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhash, V.V.; Tan, S.H.; Tan, W.L.; Yeo, M.S.; Xie, C.; Wong, F.Y.; Kiat, Z.Y.; Lim, R.; Yong, W.P. GTSE1 expression represses apoptotic signaling and confers cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Nie, G.; Guo, M. Methylation of SLFN11 promotes gastric cancer growth and increases gastric cancer cell resistance to cisplatin. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 6124–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wermann, H.; Stoop, H.; Gillis, A.J.; Honecker, F.; van Gurp, R.J.; Ammerpohl, O.; Richter, J.; Oosterhuis, J.W.; Bokemeyer, C.; Looijenga, L.H. Global DNA methylation in fetal human germ cells and germ cell tumours: Association with differentiation and cisplatin resistance. J. Pathol. 2010, 221, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Shao, C.-J.; Chen, F.-R.; Kwan, A.-L.; Chen, Z.-P. Role of ERCC1 promoter hypermethylation in drug resistance to cisplatin in human gliomas. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1944–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiyoshi, S.; Honda, S.; Minato, M.; Ara, M.; Suzuki, H.; Hiyama, E.; Taketomi, A. Hypermethylation of CSF3R is a novel cisplatin resistance marker and predictor of response to postoperative chemotherapy in hepatoblastoma. Hepatol. Res. 2020, 50, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Rao, X.; House, M.G.; Nephew, K.P.; Cullen, K.J.; Guo, Z. GPx3 promoter hypermethylation is a frequent event in human cancer and is associated with tumorigenesis and chemotherapy response. Cancer Lett. 2011, 309, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, J.; House, M.G.; Cullen, K.J.; Nephew, K.P.; Guo, Z. Role of neurofilament light polypeptide in head and neck cancer chemoresistance. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, C.T.; Dang, D.; Achdjian, S.; Ye, Y.; Katz, S.G.; Schmidt, B.L. Decitabine Rescues Cisplatin Resistance in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, W.J.; Rafferty, M.; Hegarty, S.; Gremel, G.; Ryan, D.; Fraga, M.F.; Esteller, M.; Dervan, P.A.; Gallagher, W.M. Metallothionein 1E is methylated in malignant melanoma and increases sensitivity to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Melanoma Res. 2010, 20, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Kondo, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Boumber, Y.; Konishi, K.; Guo, Y.; Chen, X.; Vilaythong, J.N.; Issa, J.P. Drug sensitivity prediction by CpG island methylation profile in the NCI-60 cancer cell line panel. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 11335–11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Song, J.; Lai, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Feng, X.; Sun, X.; Du, Z. Hypermethylation of ATP-binding cassette B1 (ABCB1) multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1) is associated with cisplatin resistance in the A549 lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2016, 97, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-E.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Tung, C.-H.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-L.; Hong, T.-M. DNA methylation maintains the CLDN1-EPHB6-SLUG axis to enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy and inhibit lung cancer progression. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8903–8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xue, X.; Fu, W.; Dai, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhong, S.; Deng, B.; Yin, J. Epigenetic activation of FOXF1 confers cancer stem cell properties to cisplatinresistant nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 56, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez de Caceres, I.; Cortes-Sempere, M.; Moratilla, C.; Machado-Pinilla, R.; Rodriguez-Fanjul, V.; Manguán-García, C.; Cejas, P.; López-Ríos, F.; Paz-Ares, L.; de CastroCarpeño, J.; et al. IGFBP-3 hypermethylation-derived deficiency mediates cisplatin resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2010, 29, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Tessema, M.; Bai, L.; Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Zheng, X.; Saxton, B.; Chen, W.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of RIP3 Suppresses Necroptosis and Increases Resistance to Chemotherapy in NonSmall Cell Lung Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-W.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.-Z.; Lu, X.-X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.-B.; Guan, X.-X.; Tong, J.-D. Integrated analysis of DNA methylation and mRNA expression profiling reveals candidate genes associated with cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, Q. Cisplatin-induced downregulation of SOX1 increases drug resistance by activating autophagy in non-small cell lung cancer cell. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 439, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, Y.B.; Park, S.Y.; Yang, S.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Hong, K.M. Transglutaminase 2 as a cisplatin resistance marker in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 136, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Yang, W.; Qin, X.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Lin, C.; Li, W.; Gu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ran, Y. ECRG4 acts as a tumor suppressor and as a determinant of chemotherapy resistance in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell. Oncol. 2015, 38, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, H.M.; Safuwan, N.A.; Chivers, P.; Papacharalbous, E.; Giannopoulos, T.; Butler-Manuel, S.; Madhuri, K.; Lovell, D.P.; Crook, T. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57(Kip2) is epigenetically regulated in carboplatin resistance and results in collateral sensitivity to the CDK inhibitor seliciclib in ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeller, C.; Dai, W.; Steele, N.L.; Siddiq, A.; Walley, A.J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.S.M.; Rizzo, S.; Van Der Zee, A.; Plumb, J.A.; Brown, R. Candidate DNA methylation drivers of acquired cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer identified by methylome and expression profiling. Oncogene 2012, 31, 4567–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, L.J.; Smith, P.R.; Hiller, L.; Szlosarek, P.W.; Kimberley, C.; Sehouli, J.; Koensgen, D.; Mustea, A.; Schmid, P.; Crook, T. Epigenetic silencing of argininosuccinate synthetase confers resistance to platinum-induced cell death but collateral sensitivity to arginine auxotrophy in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.R.; Li, S.D.; He, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.X.; Liu, X.L.; Wan, X.P. Aberrant methylation of breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene 1 in chemosensitive human ovarian cancer cells does not involve the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-Akt pathway. Cancer Sci. 2010, 101, 1618–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-L.; Su, H.-Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Liao, Y.-P.; Hartman-Frey, C.; Lai, Y.-H.; Yang, H.-W.; Deatherage, D.E.; Kuo, C.-T.; Huang, Y.-W.; et al. Promoter hypermethylation of FBXO32, a novel TGF-β/SMAD4 target gene and tumor suppressor, is associated with poor prognosis in human ovarian cancer. Lab. Investig. 2010, 90, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.A.; Rodríguez-Antolín, C.; Vera, O.; Pernía, O.; Esteban-Rodríguez, I.; Dolores Diestro, M.; Benitez, J.; Sánchez-Cabo, F.; Alvarez, R.; De Castro, J.; et al. Transcriptional epigenetic regulation of Fkbp1/Pax9 genes is associated with impaired sensitivity to platinum treatment in ovarian cancer. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathdee, G.; MacKean, M.J.; Illand, M.; Brown, R. A role for methylation of the hMLH1 promoter in loss of hMLH1 expression and drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.N.; Sung, H.Y.; Yang, S.D.; Chae, Y.J.; Ju, W.; Ahn, J.H. Epigenetic modification of alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase enhances cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer. Korean J. Physiol. Pharm. 2018, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.D.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, J.I. 3-Oxoacid CoA transferase 1 as a therapeutic target gene for cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 2611–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.Y.; Lai, H.C.; Lin, Y.W.; Liu, C.Y.; Chen, C.K.; Chou, Y.C.; Lin, S.P.; Lin, W.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Yu, M.H. Epigenetic silencing of SFRP5 is related to malignant phenotype and chemoresistance of ovarian cancer through Wnt signaling pathway. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogales, V.; Reinhold, W.C.; Varma, S.; Martinez-Cardus, A.; Moutinho, C.; Moran, S.; Heyn, H.; Sebio, A.; Barnadas, A.; Pommier, Y.; et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the putative DNA/RNA helicase SLFN11 in human cancer confers resistance to platinum drugs. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 3084–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leon, M.; Cardenas, H.; Vieth, E.; Emerson, R.; Segar, M.; Liu, Y.; Nephew, K.; Matei, D. Transmembrane protein 88 (TMEM88) promoter hypomethylation is associated with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsch, D.; Hoffmann, F.; Steinbach, D.; Jansen, L.; Mary Photini, S.; Gajda, M.; Mosig, A.S.; Sonnemann, J.; Peters, S.; Melnikova, M.; et al. Tribbles 2 mediates cisplatin sensitivity and DNA damage response in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Sun, T.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Jing, M. Estrogen receptor-α promoter methylation is a biomarker for outcome prediction of cisplatin resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 15, 2855–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunch, B.; Krishnan, N.; Greenspan, R.D.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Attwood, K.; Yan, L.; Qi, Q.; Wang, D.; Morrison, C.; Omilian, A.; et al. TAp73 expression and P1 promoter methylation, a potential marker for chemoresponsiveness to cisplatin therapy and survival in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, M.P.; Tanzer, M.; Balluff, B.; Burgermeister, E.; Kretzschmar, A.K.; Hughes, D.J.; Tetzner, R.; Lofton-Day, C.; Rosenberg, R.; Reinacher-Schick, A.C.; et al. TFAP2E-DKK4 and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Herman, J.G.; Brock, M.V.; Zhao, P.; Guo, M. Predictive value of CHFR and MLH1 methylation in human gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2015, 18, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, S.; McKiernan, J.M.; Narayan, G.; Houldsworth, J.; Bacik, J.; Dobrzynski, D.L.; Assaad, A.M.; Mansukhani, M.; Reuter, V.E.; Bosl, G.J.; et al. Role of promoter hypermethylation in Cisplatin treatment response of male germ cell tumors. Mol. Cancer 2004, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cortés-Sempere, M.; de Miguel, M.P.; Pernía, O.; Rodriguez, C.; de Castro Carpeño, J.; Nistal, M.; Conde, E.; López-Ríos, F.; Belda-Iniesta, C.; Perona, R.; et al. IGFBP-3 methylation-derived deficiency mediates the resistance to cisplatin through the activation of the IGFIR/Akt pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasse, S.; Lienhard, M.; Frese, S.; Kerick, M.; Steinbach, A.; Grimm, C.; Hussong, M.; Rolff, J.; Becker, M.; Dreher, F.; et al. Epigenomic profiling of non-small cell lung cancer xenografts uncover LRP12 DNA methylation as predictive biomarker for carboplatin resistance. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yan, L.; Xiao-Fei, L.; Hai-Yan, S.; Juan, C.; Shan, K. Hypermethylation of mismatch repair gene hMSH2 associates with platinum-resistant disease in epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.W.; Lam, W.-Y.; Chen, F.; Yung, M.M.H.; Chan, Y.-S.; Chan, W.-S.; He, F.; Liu, S.S.; Chan, K.K.L.; Li, B.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylome analysis identifies methylation signatures associated with survival and drug resistance of ovarian cancers. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Hua, T.; Zhang, H.B.; Tian, Y.J.; Li, Y.; Kang, S. Promoter Methylation of the MGRN1 Gene Predicts Prognosis and Response to Chemotherapy of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Patients. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 659254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, T.; Alkema, N.G.; Schreuder, L.; Meersma, G.J.; de Meyer, T.; van Criekinge, W.; Klip, H.G.; Fiegl, H.; van Nieuwenhuysen, E.; Vergote, I.; et al. Methylome analysis of extreme chemoresponsive patients identifies novel markers of platinum sensitivity in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.S.; Teaberry, V.S.; Bland, A.E.; Huang, Z.; Whitaker, R.S.; Baba, T.; Fujii, S.; Secord, A.A.; Berchuck, A.; Murphy, S.K. Elevated MAL expression is accompanied by promoter hypomethylation and platinum resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, X.-X.; Li, M.-C.; Cao, C.-H.; Wan, D.-Y.; Xi, B.-X.; Tan, J.-H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Feng, X.-X.; et al. C/EBPβ enhances platinum resistance of ovarian cancer cells by reprogramming H3K79 methylation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senga, S.S.; Grose, R.P. Hallmarks of cancer—the new testament. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 200358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.M.; Wilson, A.; Koo, C.; Masrour, N.; Gallon, J.; Loomis, E.; Flower, K.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.; Hergovich, A.; Cunnea, P.; et al. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Induces Methylation Changes in Blood DNA Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2213–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, A.; Kothandapani, A.; Zhitkovich, A.; Sobol, R.W.; Patrick, S.M. Role of mismatch repair proteins in the processing of cisplatin interstrand cross-links. DNA Repair. 2015, 35, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- No, J.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Song, Y.S. Targeting nrf2 signaling to combat chemoresistance. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 19, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Wu, R.; Guo, Y.; Kong, A.N. Regulation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling: The role of epigenetics. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2016, 1, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossetta, G.; Fantone, S.; Montanari, E.; Marzioni, D.; Goteri, G. Role of NRF2 in Ovarian Cancer. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, E.; Rothwell, D.G.; Brady, G.; Dive, C. Liquid Biopsy-Based Biomarkers of Treatment Response and Resistance. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Hattori, N.; Kushima, R.; Lee, Y.-C.; Igaki, H.; Tachimori, Y.; Nagino, M.; Ushijima, T. Estimation of the Fraction of Cancer Cells in a Tumor DNA Sample Using DNA Methylation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Venkatesh, A.; Ray, S.; Srivastava, S. Challenges and prospects for biomarker research: A current perspective from the developing world. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1844, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.E.; Wang, J.; Mitchell, H.; Webb-Robertson, B.-J.; Hafen, R.; Ramey, J.; Rodland, K.D. Challenges in biomarker discovery: Combining expert insights with statistical analysis of complex omics data. Expert Opin. Med. Diagn. 2013, 7, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertel, A.; Verghese, A.; Byers, S.W.; Ochs, M.; Tozeren, A. Pathway-specific differences between tumor cell lines and normal and tumor tissue cells. Mol. Cancer 2006, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Thoburn, C.; Afsari, B.; Danilova, L.; Douville, C.; Javed, A.A.; Wong, F.; Mattox, A.; et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 2018, 359, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Clinical Applications of Circulating Tumor Cells and Circulating Tumor DNA as Liquid Biopsy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, P.; Aboagye, E.O.; Balkwill, F.; Balmain, A.; Bruder, G.; Chaplin, D.J.; Double, J.A.; Everitt, J.; Farningham, D.A.H.; Glennie, M.J.; et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1555–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, W.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wu, F.; Sun, G.; Sun, G.; Lv, C.; Hui, B. Application of Animal Models in Cancer Research: Recent Progress and Future Prospects. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 2455–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, A.; Altucci, L. Epi-drugs to fight cancer: From chemistry to cancer treatment, the road ahead. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebbioso, A.; Carafa, V.; Benedetti, R.; Altucci, L. Trials with ‘epigenetic’ drugs: An update. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulonis, U.; Berlin, S.; Lee, H.; Whalen, C.; Obermayer, E.; Penson, R.; Liu, J.; Campos, S.; Krasner, C.; Horowitz, N. Phase I study of combination of vorinostat, carboplatin, and gemcitabine in women with recurrent, platinum-sensitive epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 76, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabb, S.J.; Danson, S.; Catto, J.W.F.; Hussain, S.; Chan, D.; Dunkley, D.; Downs, N.; Marwood, E.; Day, L.; Saunders, G.; et al. Phase I Trial of DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor Guadecitabine Combined with Cisplatin and Gemcitabine for Solid Malignancies Including Urothelial Carcinoma (SPIRE). Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1882–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).