Oral Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: Progression to Malignancy and Clinical Implications. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- White/keratotic lesions that can be smooth, fissured, verrucous, or erythematous, with or without the presence of ulcerated areas.

- (2)

- Non-contiguous multifocal lesions or single lesions larger than 4 cm in a single site or single lesions larger than 3 cm with the involvement of contiguous sites.

- (3)

- Lesions that progress/expand and/or develop multifocality over time.

- (4)

- Histopathology, which, in absence of dysplasia or carcinoma, still shows hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, atrophy, or acanthosis with minimal or absent cytological atypia, with or without the presence of a lymphocytic band, or verrucous hyperplasia.

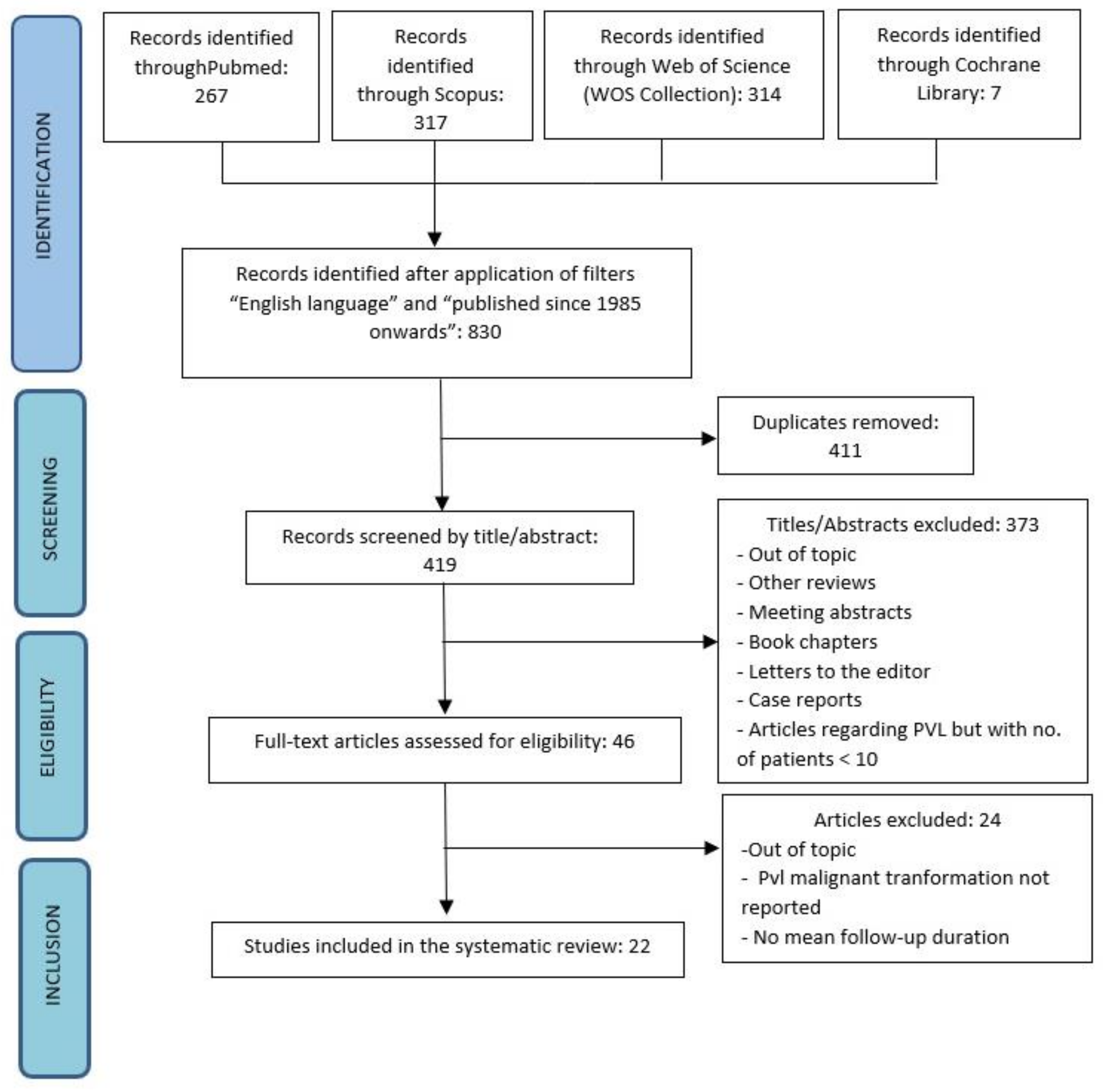

2. Materials and Methods

- −

- PubMed.

- −

- Scopus.

- −

- Web of Science (WOS Core Collection).

- −

- Cochrane Library.

- −

- Studies involving at least 10 PVL patients.

- −

- Diagnosis of PVL carried out on the basis of the criteria defined by Hansen et al. [2], or subsequent modifications.

- −

- Studies reporting the number of patients who, over time, developed oral cancer as a consequence of PVL neoplastic transformation.

- −

- Articles in which the mean follow-up of PVL patients was explicitly reported.

- First author;

- Year of publication;

- Country in which the study was conducted;

- Enrolment period of patients;

- Type of study with any statistical analysis applied;

- Number of patients with PVL diagnosis;

- Gender;

- Mean age;

- Mean duration of follow-up;

- Current or past use of tobacco or alcohol;

- Number of patients who underwent neoplastic transformation of the lesion, including the number of men and women;

- Subjects who developed verrucous carcinoma or conventional oral squamous cell carcinoma (included gender);

- Number of patients who developed multiple carcinomas in different intraoral sites;

- Mean time from diagnosis of PVL to neoplastic transformation;

- Mean number of biopsies per patient;

- Mean time between first and eventual second primary oral carcinoma;

- Number of patients who died from causes related to oral carcinoma;

- The site most frequently involved by the onset of PVL or by malignant transformation.

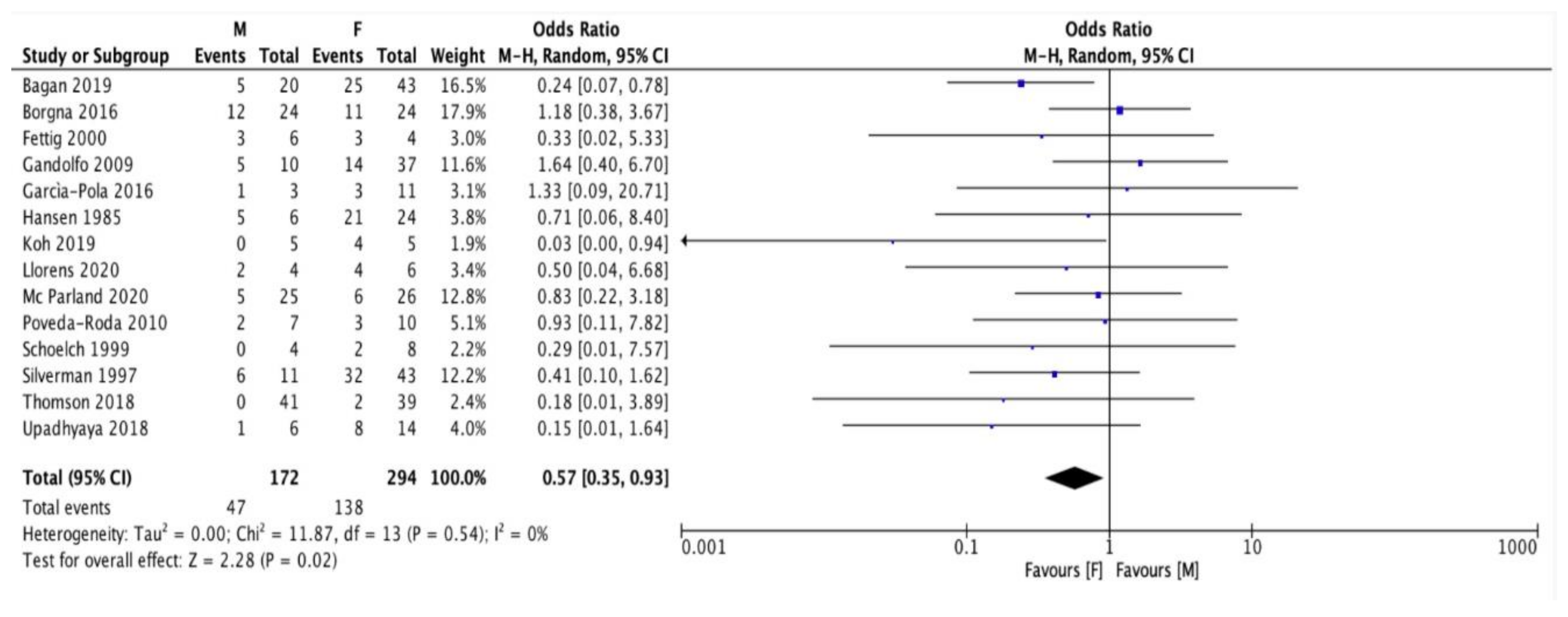

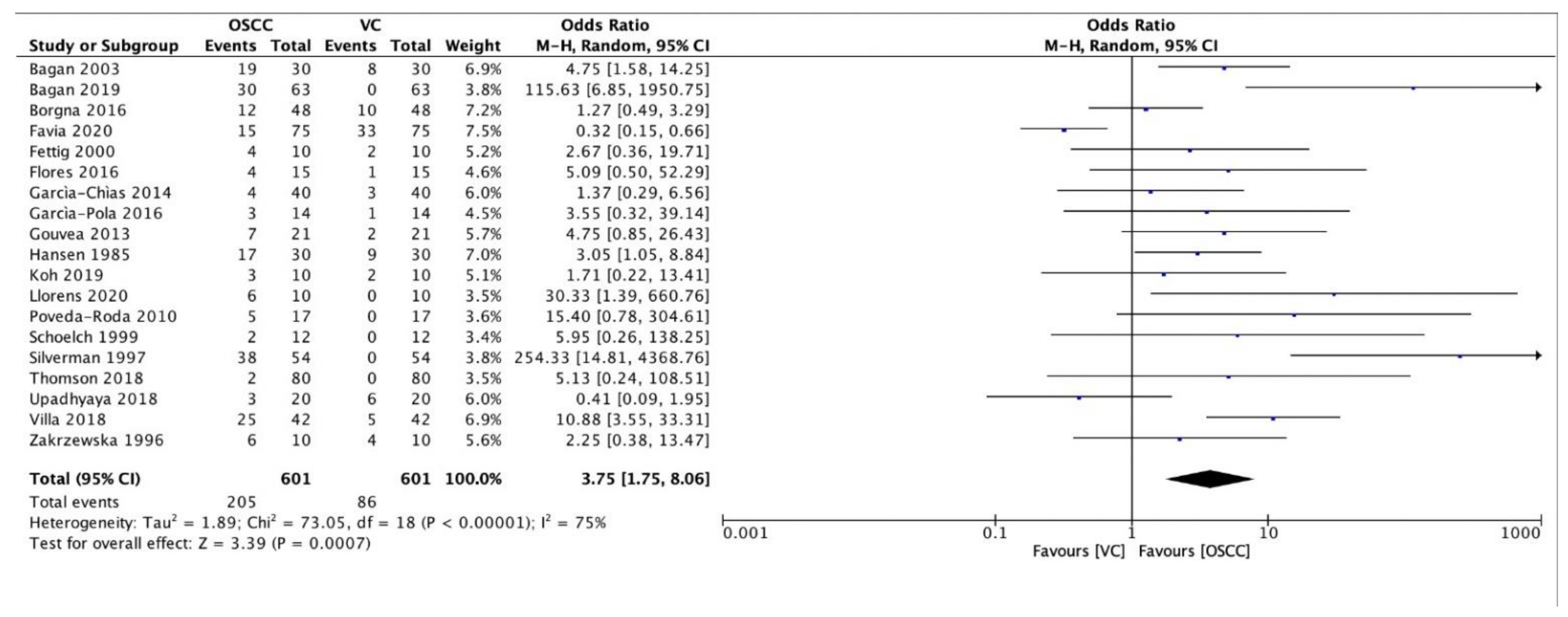

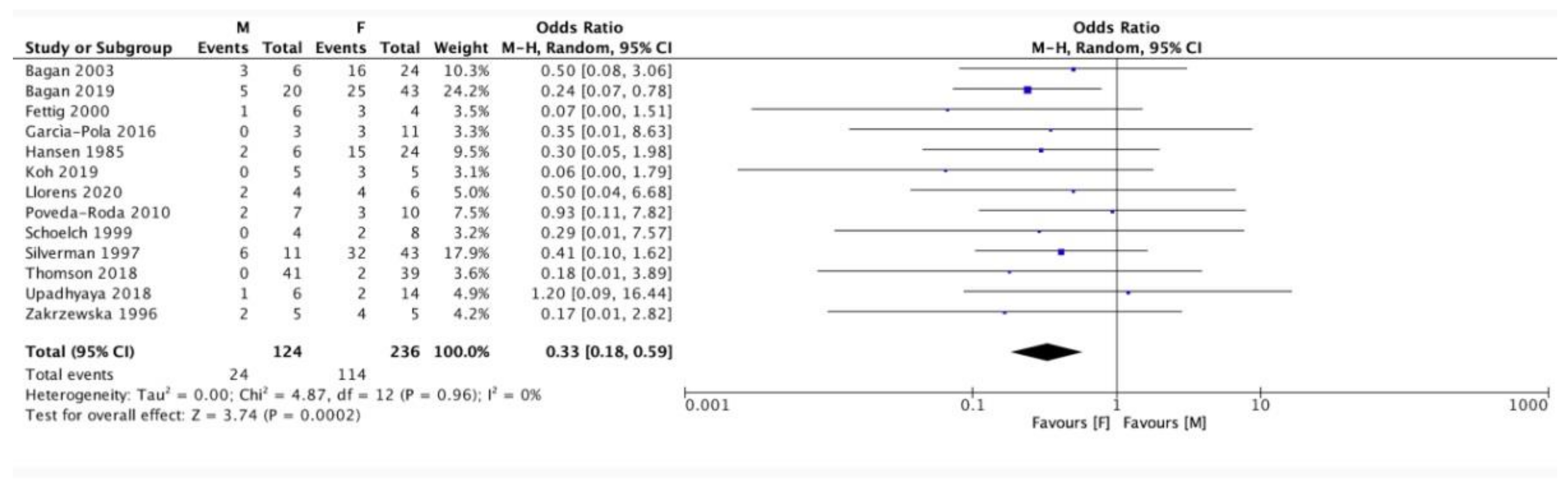

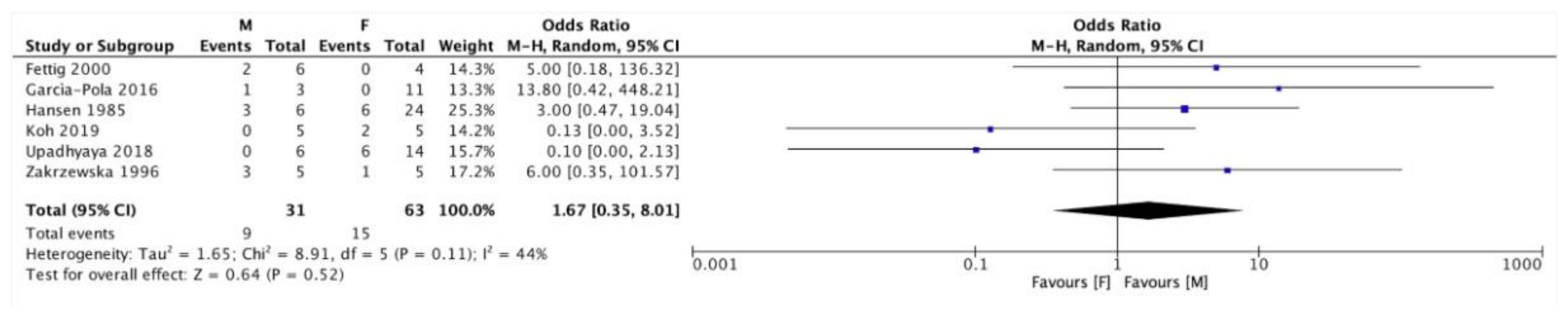

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Kujan, O.; Aguirre-Urizar, J.M.; Bagan, J.V.; González-Moles, M.; Kerr, A.R.; Lodi, G.; Mello, F.W.; Monteiro, L.; Ogden, G.R.; et al. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.S.; Olson, J.A.; Silverman, S., Jr. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1985, 60, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerero-Lapiedra, R.; Balade-Martinez, D.; Moreno-López, L.A.; Esparza-Gomez, G.; Bagan, J. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A proposal for diagnostic criteria. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2010, 15, e839–e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carrard, V.C.; Brouns, E.R.; van der Waal, I. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia; a critical appraisal of the diagnostic criteria. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2013, 18, e411–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Menon, R.S.; Kerr, A.R.; De Abreu, A.F.; Guollo, A.; Ojeda, D.; Woo, S.B. Proliferative leukoplakia: Proposed new clinical diagnostic criteria. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Jawanda, M.K.; Madhushankari, G.S. Current challenges and the diagnostic pitfalls in the grading of epithelial dysplasia in oral potentially malignant disorders: A review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 10, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, J.; Van Dis, M.; Zakrzewska, J.; Lopes, V.; Speight, P.; Hopper, C. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A report of ten cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 1996, 82, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S., Jr.; Gorsky, M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A follow-up study of 54 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 1997, 84, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoelch, M.L.; Sekandari, N.; Regezi, J.A.; Silverman, S., Jr. Laser management of oral leukoplakias: A follow-up study of 70 patients. Laryngoscope 1999, 109, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fettig, A.; Pogrel, M.A.; Silverman, S., Jr.; Bramanti, T.E.; Da Costa, M.; Regezi, J.A. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia of the gingiva. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 2000, 90, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagan, J.V.; Jimenez, Y.; Sanchis, J.M.; Poveda, R.; Milian, M.A.; Murillo, J.; Scully, C. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: High incidence of gingival squamous cell carci-noma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2003, 32, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagán, J.V.; Murillo, J.; Poveda, R.; Gavaldá, C.; Jiménez, Y.; Scully, C. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Unusual locations of oral squamous cell carcinomas, and field cancerization as shown by the appearance of multiple OSCCs. Oral Oncol. 2004, 40, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfo, S.; Castellani, R.; Pentenero, M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A potentially malignant disorder involving periodontal sites. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda-Roda, R.; Bagan, J.; Jimenez-Soriano, Y.; Diaz-Fernandez, J.; Gavalda-Esteve, C. Retinoids and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL). A preliminary study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2009, 15, e3–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gouvêa, A.F.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; Speight, P.M.; Hunter, K.; Carlos, R.; Vargas, P.A.; De Almeida, O.P.; Lopes, M.A. High incidence of DNA ploidy abnormalities and increased Mcm2 expression may predict malignant change in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Histopathology 2013, 62, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Chias, B.; Casado-De La Cruz, L.; Esparza-Gomez, G.; Cerero-Lapiedra, R. Diagnostic criteria in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Evaluation. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2014, 19, e335–e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, I.L.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; Della Coletta, R.; Leme, A.F.P.; Lopes, M.A. Low expression of angiotensinogen and dipeptidyl peptidase 1 in saliva of patients with proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. World J. Clin. Cases 2016, 4, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pola, M.J.; Llorente-Pendas, S.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.; Garcia-Martin, J.M. The development of proliferative verrucous leu-koplakia in oral lichen planus. A preliminary study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e328–e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgna, S.C.; Clarke, P.T.; Schache, A.G.; Lowe, D.; Ho, M.W.; McCarthy, C.E.; Adair, S.; Field, E.A.; Field, J.K.; Holt, D.; et al. Management of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: Justification for a conservative approach. Head Neck 2017, 39, 1997–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.J.; Goodson, M.L.; Smith, D.R. Potentially malignant disorders revisited—The lichenoid lesion/proliferative verrucous leukoplakia conundrum. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, J.D.; Fitzpatrick, S.G.; Islam, M.N.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Cohen, D.M. A Retrospective 20-Year Analysis of Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia and Its Progression to Malignancy and Association with High-risk Human Papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 2018, 12, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagan, J.; Murillo-Cortes, J.; Leopoldo-Rodado, M.; Sanchis-Bielsa, J.M.; Bagan, L. Oral cancer on the gingiva in patients with proliferative leukoplakia: A study of 30 cases. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, J.; Kurago, Z.B. Expanded Expression of Toll-Like Receptor 2 in Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia. Head Neck Pathol. 2019, 13, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favia, G.; Capodiferro, S.; Limongelli, L.; Tempesta, A.; Maiorano, E. Malignant transformation of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A series of 48 patients with suggestions for management. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 50, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, C.; Soriano, B.; Trilla-Fuertes, L.; Bagan, L.; Ramos-Ruiz, R.; Gamez-Pozo, A.; Peña, C.; Bagan, J.V. Immune expression profile identification in a group of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia patients: A pre-cancer niche for oral squamous cell carcinoma development. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 25, 2645–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McParland, H.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Lichenoid morphology could be an early feature of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 50, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.K.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Bigby, M.; Callen, J.P. Systematic reviews: Grading recommendations and evidence quality. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadie, W.M.; Partington, E.J.; Fowler, C.B.; Schmalbach, C.E. Optimal Management of Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 153, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrejon-Moya, A.; Jané-Salas, E.; López-López, J. Clinical manifestations of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A system-atic review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 49, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentenero, M.; Meleti, M.; Vescovi, P.; Gandolfo, S. Oral proliferative verrucous leucoplakia: Are there particular features for such an ambiguous entity? A systematic review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 170, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagan, J.V.; Jiménez-Soriano, Y.; Diaz-Fernandez, J.M.; Murillo-Cortés, J.; Sanchis-Bielsa, J.M.; Poveda-Roda, R.; Bagan, L. Malignant transformation of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia to oral squamous cell carcinoma: A series of 55 cases. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouquot, J.E. Oral verrucous carcinoma: Incidence in two US populations. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 1998, 86, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R.; Varghese, I.; Sugathan, C.K. Ackerman’s tumour (verrucous carcinoma) of the oral cavity: A clinicepidemiological study of 426 cases. Aust. Dent. J. 1988, 23, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, L.V. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery 1948, 23, 670–678. [Google Scholar]

- Bagan, J.; Murillo-Cortes, J.; Poveda-Roda, R.; Leopoldo-Rodado, M.; Bagan, L. Second primary tumors in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: A series of 33 cases. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 24, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaughter, D.; Southwick, H.; Smejkal, W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous cell carcinoma: Clinical implications of multicentric origins. Cancer 1953, 6, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakhuis, B.J.M.; Tabor, M.P.; Kummer, J.A.; Leemans, C.R.; Brakenhoff, R.H. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: Evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 1727–1730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simple, M.; Suresh, A.; Das, D.; Kuriakose, M.A. Cancer stem cells and field cancerization of Oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2015, 51, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, R.; Weghorst, C.M.; Lehman, T.A.; Calvert, R.J.; Bijur, G.; Sabourin, C.L.; Mallery, S.R.; Schuller, D.E.; Stoner, G.D. Mutated and wild-type p53 expression and HPV integration in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontol. 1997, 83, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palefsky, J.M.; Silverman, S., Jr.; Abdel-Salaam, M.; Daniels, T.E.; Greenspan, J.S. Association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and infection with human papillomavirus type 16. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1995, 24, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, G.; Giovannelli, L.; Ammatuna, P.; Capra, G.; Colella, G.; Di Liberto, C.; Gandolfo, S.; Pentenero, M.; Carrozzo, M.; Serpico, R.; et al. Proliferative verrucous vs. conventional leukoplakia: No significantly increased risk of HPV infection. Oral Oncol. 2004, 40, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagan, J.V.; Jimenez, Y.; Murillo, J.; Gavaldá, C.; Poveda, R.; Scully, C.; Alberola, T.M.; Torres-Puente, M.; Pérez-Alonso, M. Lack of association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and human papillomavirus infection. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axell, T.; Holmstrup, P.; Kramer, J.R.; Pindborg, J.J.; Shear, M. International seminar on oral leukoplakia and associated lesions re-lated to tobacco habits. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1984, 12, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrish, S.; Ben-Izhak, O.; Sabo, E.; Rachmiel, A. Oral squamous cell carcinoma associated with proliferative verrucous leukoplakia compared with conventional squamous cell carcinoma—A clinical, histologic and immunohistochemical study. Oral Surg Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 119, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Year of Publication | Number of PVL Patients | Patients Enrolment Period | Type of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hansen et al. [2] | 1985 | 30 | 1961–1983 | Retrospective case series |

| Zakrzewska et al. [7] | 1996 | 10 | - | Case series |

| Silverman e Gorsky [8] | 1997 | 54 | - | Case series |

| Schoelch et al. [9] | 1999 | 12 | - | Case series |

| Fettig et al. [10] | 2000 | 10 | 1995–1999 | Case series |

| Bagan et al. [11] | 2003 | 30 | - | Case control |

| Bagan et al. [12] | 2004 | 19 | - | Case series |

| Gandolfo et al. [13] | 2009 | 47 | 1981–2006 | Retrospective case control |

| Poveda-Roda et al. [14] | 2010 | 17 | - | Preliminary study |

| Gouvea et al. [15] | 2013 | 21 | - | Retrospective case control |

| Garcìa-Chìas et al. [16] | 2014 | 40 | 1984–2011 | Retrospective case series |

| Flores et al. [17] | 2016 | 15 | - | Case control |

| Garcìa-Pola et al. [18] | 2016 | 14 | 1984–2015 | Observational descriptive study |

| Borgna et al. [19] | 2016 | 48 | 1990–2015 | Retrospective case series |

| Thomson et al. [20] | 2018 | 80 | 1996–2014 | Retrospective cohort |

| Upadhyaya et al. [21] | 2018 | 20 | 1994–2016 | Retrospective case series |

| Villa et al. [5] | 2018 | 42 | 1996–2016 | Retrospective case series |

| Bagan et al. [22] | 2019 | 63 | 2003–2018 | Retrospective observational clinical study |

| Koh et al. [23] | 2019 | 10 | - | Case control |

| Favia et al. [24] | 2020 | 75 | 1989–2008 | Retrospective case series |

| Llorens et al. [25] | 2020 | 10 | - | Retrospective case control |

| McParland and Warnakulasuriya [26] | 2020 | 51 | - | Retrospective case series |

| Authors | Year of Publication | Grade of Recommendation | Quality of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hansen et al. [2] | 1985 | 2A | C |

| Zakrzewska et al. [7] | 1996 | 2A | C |

| Silverman and Gorsky [8] | 1997 | 2A | C |

| Schoelch et al. [9] | 1999 | 2A | C |

| Fettig et al. [10] | 2000 | 2A | C |

| Bagan et al. [11] | 2003 | 2A | B |

| Bagan et al. [12] | 2004 | 2A | C |

| Gandolfo et al. [13] | 2009 | 2A | B |

| Poveda-Roda et al. [14] | 2010 | 2A | B |

| Gouvea et al. [15] | 2013 | 2A | B |

| Garcìa-Chìas et al. [16] | 2014 | 2A | C |

| Flores et al. [17] | 2016 | 2A | B |

| Garcìa-Pola et al. [18] | 2016 | 2A | C |

| Borgna et al. [19] | 2016 | 2A | C |

| Thomson et al. [20] | 2018 | 2A | B |

| Upadhyaya et al. [21] | 2018 | 2A | C |

| Villa et al. [5] | 2018 | 2A | C |

| Bagan et al. [22] | 2019 | 2A | C |

| Koh et al. [23] | 2019 | 2A | B |

| Favia et al. [24] | 2020 | 2A | C |

| Llorens et al. [25] | 2020 | 2A | B |

| McParland and Warnakulasuriya [26] | 2020 | 2A | C |

| Authors | Number of PVL Patients | M | F | Tobacco Use | Mean Follow-Up (Y) | Number of PVL Patients with Malignant Transformation | Number of Patients with Multiple Oral Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hansen 1985 [2] | 30 | 6 | 24 | 18 | 6.1 | 26/30 | - |

| Zakrzewska 1996 [7] | 10 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6.6 | 10/10 | - |

| Silverman 1997 [8] | 54 | 11 | 43 | 17 | 11.6 | 38/54 | 12/38 |

| Schoelch 1999 [9] | 12 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2/12 | - |

| Fettig 2000 [10] | 10 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4.4 | 6/10 | - |

| Bagan 2003/2004 [11,12] | 30 | 6 | 24 | 7 | 4.7 | 27/30 | 10/19 |

| Gandolfo 2009 [13] | 47 | 10 | 37 | 17 | 6.8 | 19/47 | 8/19 |

| Poveda-Roda 2010 [14] | 17 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 6.6 | 5/17 | 3/5 |

| Gouvea 2013 [15] | 21 | 3 | 18 | 4 | 7.3 | 9/21 | 2/9 |

| Garcìa-Chìas 2014 [16] | 40 | 15 | 25 | 13 | 3.6 | 7/40 | - |

| Flores 2016 [17] | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 5.4 | 4/15 | 2/4 |

| Garcìa-Pola 2016 [18] | 14 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 14.5 | 4/14 | - |

| Borgna 2016 [19] | 48 | 24 | 24 | 33 | 4.3 | 23/48 | - |

| Thomson 2018 [20] | 80 | 41 | 39 | - | 4 | 2/80 | - |

| Upadhyaya 2018 [21] | 20 | 6 | 14 | 12 | 7.6 | 9/20 | 3/9 |

| Villa 2018 [5] | 42 | 7 | 35 | 17 | 4.5 | 30/42 | 10/30 |

| Bagan 2019 [22] | 63 | 20 | 43 | 25 | 6 (median) | 30/63 | - |

| Koh 2019 [23] | 10 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3.3 | 4/10 | - |

| Favia 2020 [24] | 75 | - | - | - | 5.2 (median) | 48/75 | 33/48 |

| Llorens 2020 [25] | 10 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 12.2 | 6/10 | 4/6 |

| McParland 2020 [26] | 51 | 25 | 26 | 22 | 16 | 11/51 | - |

| Total | 699 | 208 | 416 | 218/544 | 7.2 | 320/699 | 87/187 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palaia, G.; Bellisario, A.; Pampena, R.; Pippi, R.; Romeo, U. Oral Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: Progression to Malignancy and Clinical Implications. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4085. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164085

Palaia G, Bellisario A, Pampena R, Pippi R, Romeo U. Oral Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: Progression to Malignancy and Clinical Implications. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2021; 13(16):4085. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164085

Chicago/Turabian StylePalaia, Gaspare, Amelia Bellisario, Riccardo Pampena, Roberto Pippi, and Umberto Romeo. 2021. "Oral Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: Progression to Malignancy and Clinical Implications. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Cancers 13, no. 16: 4085. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164085

APA StylePalaia, G., Bellisario, A., Pampena, R., Pippi, R., & Romeo, U. (2021). Oral Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia: Progression to Malignancy and Clinical Implications. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers, 13(16), 4085. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164085