Behavioral and Psychological Outcomes Associated with Skin Cancer Genetic Testing in Albuquerque Primary Care

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

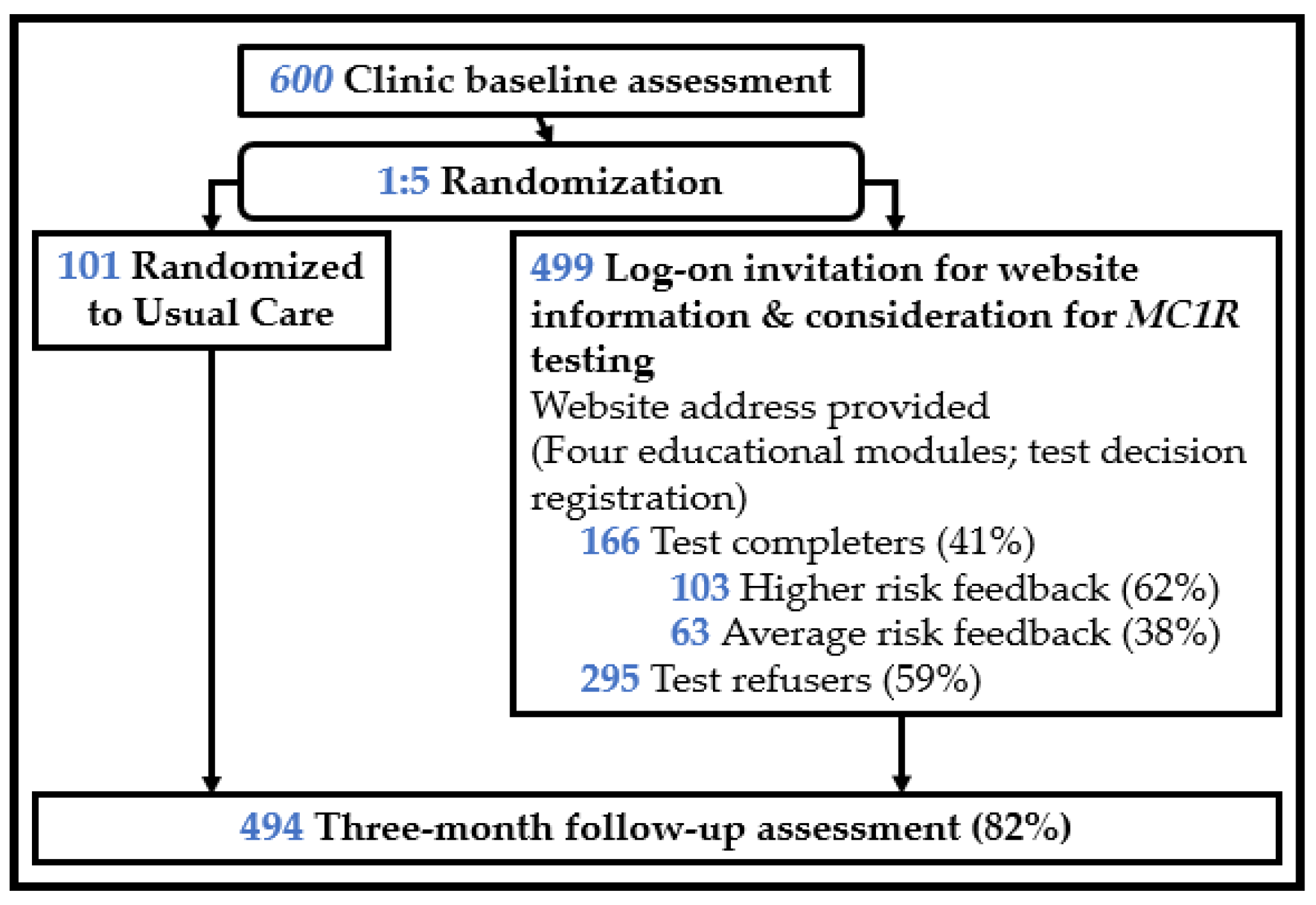

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcome Measures

2.3.2. Predictors

2.3.3. Moderators

2.4. Biostatistical Approach

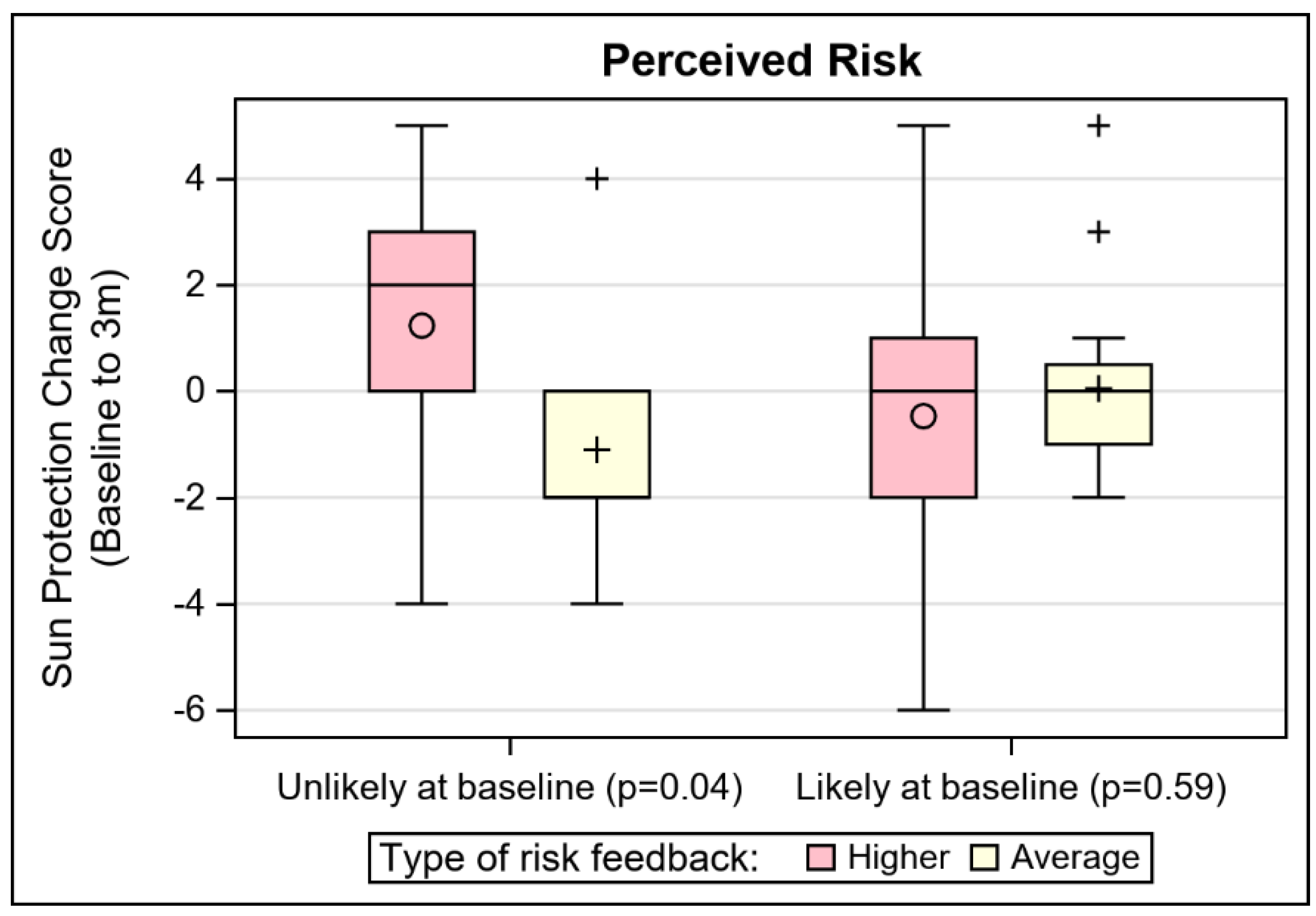

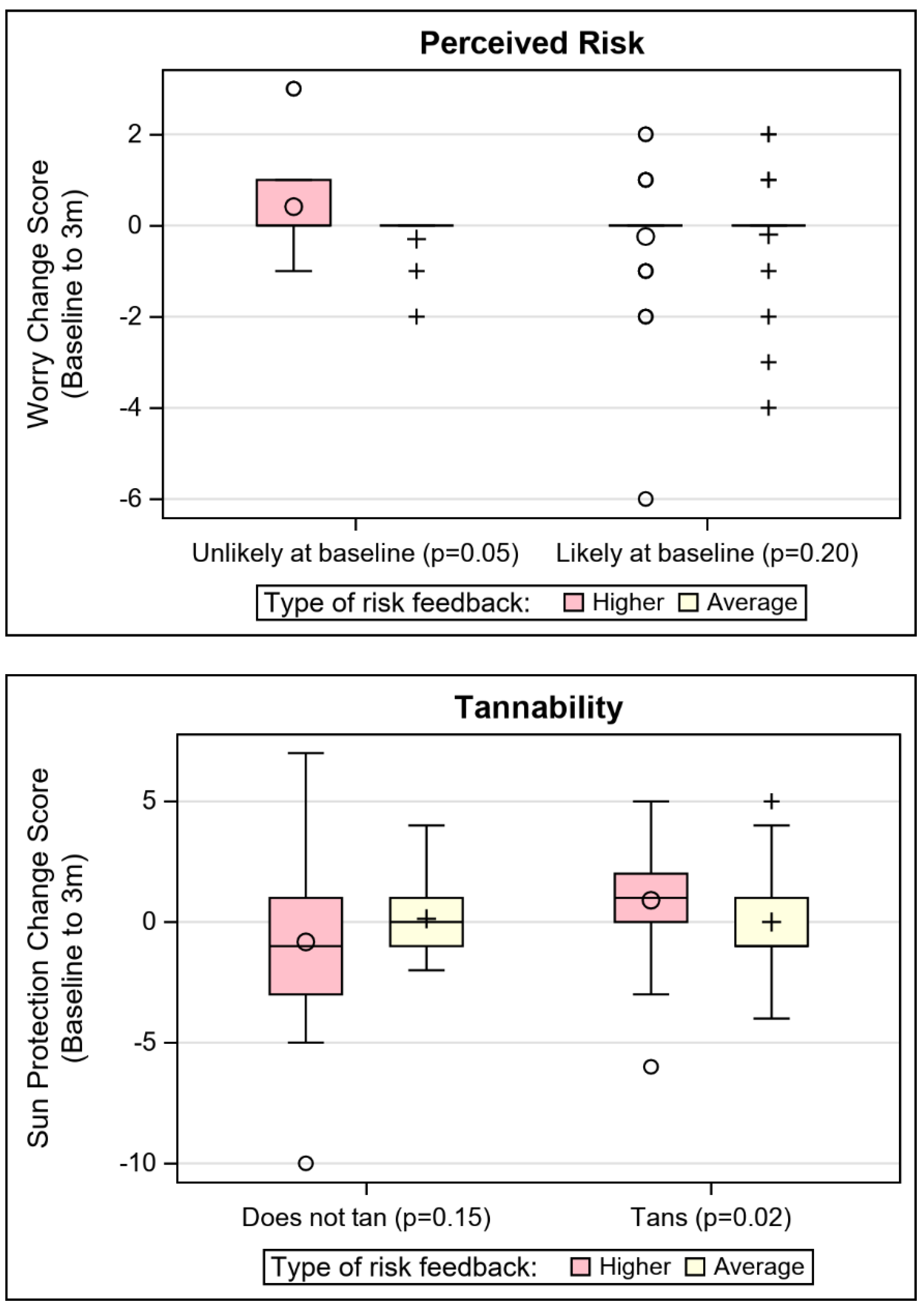

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvord, T.W.; Marriott, L.K.; Nguyen, P.T.; Shafer, A.; Brown, K.; Stoller, W.; Volpi, J.L.; Vandehey-Guerrero, J.; Ferrara, L.K.; Blakesley, S.; et al. Public perception of predictive cancer genetic testing and research in Oregon. J. Genet. Couns. 2020, 29, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regalado, A. More than 26 million people have taken an at-home ancestry test. MIT Technol. Rev. 2019, 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Feero, W.G.; Wicklund, C.A. Consumer Genomic Testing in 2020. JAMA 2020, 323, 1445–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Roundtable on Genomics and Precision Health. Exploring the Current Landscape of Consumer Genomics: Proceedings of a Workshop; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agurs-Collins, T.; Ferrer, R.; Ottenbacher, A.; Waters, E.A.; O’Connell, M.E.; Hamilton, J.G. Public Awareness of Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Tests: Findings from the 2013 U.S. Health Information National Trends Survey. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 30, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apathy, N.C.; Menser, T.; Keeran, L.M.; Ford, E.W.; Harle, C.A.; Huerta, T.R. Trends and Gaps in Awareness of Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Tests from 2007 to 2014. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, N.M.; Blum-Barnett, E.; Madrid, S.D.; Jonas, C.; Janes, K.; Alvarado, M.; Bedoy, R.; Paolino, V.; Aziz, N.; McGlynn, E.A.; et al. Demographic differences in the utilization of clinical and direct-to-consumer genetic testing. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 29, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetterstrand, K. DNA Sequencing Costs: Data. Available online: https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/DNA-Sequencing-Costs-Data (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Hay, J.L.; Bowers, J.M.; Hamilton, J.G. Genomics and behavior change. In The Handbook of Health Psychology, 3rd ed.; Revenson, T.A., Gurung, R.A.R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 474–483. [Google Scholar]

- Bloss, C.S.; Ornowski, L.; Silver, E.; Cargill, M.; Vanier, V.; Schork, N.J.; Topol, E.J. Consumer perceptions of direct-to-consumer personalized genomic risk assessments. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Krapcho, M.; Garshell, J.; Miller, D.; Altekruse, S.F.; Kosary, C.L.; Yu, M.; Ruhl, J.; Tatalovich, Z.; Mariotto, A.; et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, H.K.; Marrett, L.D.; Cokkinides, V.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.; Patel, P.; Tai, E.; Jemal, A.; Li, J.; Kim, J.; Ekwueme, D.U. Melanoma in adolescents and young adults (ages 15–39 years): United States, 1999–2006. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, S38–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Geller, A.C.; Tucker, M.A.; Guy, G.P., Jr.; Weinstock, M.A. Melanoma burden and recent trends among non-Hispanic whites aged 15–49 years, United States. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- American Cancer Society. Types of Cancers That Develop in Young Adults. 2019. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-in-young-adults/cancers-in-young-adults.html (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2020. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Rogers, H.W.; Weinstock, M.A.; Feldman, S.R.; Coldiron, B.M. Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the U.S. Population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagas, M.R.; Greenberg, E.R.; Spencer, S.K.; Stukel, T.A.; Mott, L.A. Increase in incidence rates of basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer in New Hampshire, USA. New Hampshire Skin Cancer Study Group. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 81, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzic, J.G.; Schmitt, A.R.; Wright, A.C.; Alniemi, D.T.; Zubair, A.S.; Olazagasti Lourido, J.M.; Sosa Seda, I.M.; Weaver, A.L.; Baum, C.L. Incidence and Trends of Basal Cell Carcinoma and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Population-Based Study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, G.P., Jr.; Machlin, S.R.; Ekwueme, D.U.; Yabroff, K.R. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002–2006 and 2007–2011. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 48, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, B.K.; Kricker, A. How much melanoma is caused by sun exposure? Melanoma Res. 1993, 3, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandini, S.; Sera, F.; Cattaruzza, M.S.; Pasquini, P.; Picconi, O.; Boyle, P.; Melchi, C.F. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandini, S.; Autier, P.; Boniol, M. Reviews on sun exposure and artificial light and melanoma. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011, 107, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.M.; Barrett, J.H.; Bishop, D.T.; Armstrong, B.K.; Bataille, V.; Bergman, W.; Berwick, M.; Bracci, P.M.; Elwood, J.M.; Ernstoff, M.S.; et al. Sun exposure and melanoma risk at different latitudes: A pooled analysis of 5700 cases and 7216 controls. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, V.; Lear, J.T.; Szeimies, R.M. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Lancet 2010, 375, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricker, A.; Weber, M.; Sitas, F.; Banks, E.; Rahman, B.; Goumas, C.; Kabir, A.; Hodgkinson, V.S.; van Kemenade, C.H.; Waterboer, T.; et al. Early Life UV and Risk of Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinoma in New South Wales, Australia. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, E.; Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Gandini, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Bagnardi, V.; Specchia, C.; Liu, F.; Kayser, M.; Nijsten, T.; et al. MC1R variants increased the risk of sporadic cutaneous melanoma in darker-pigmented Caucasians: A pooled-analysis from the M-SKIP project. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanetsky, P.A.; Panossian, S.; Elder, D.E.; Guerry, D.; Ming, M.E.; Schuchter, L.; Rebbeck, T.R. Does MC1R genotype convey information about melanoma risk beyond risk phenotypes? Cancer 2010, 116, 2416–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, A.K.; Collazo-Roman, M.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Valavanis, S.; Del Rio, J.; Soto, B.; Flores, I.; Dutil, J.; Kanetsky, P.A. MC1R variants and associations with pigmentation characteristics and genetic ancestry in a Hispanic, predominately Puerto Rican, population. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, S.; Sera, F.; Gandini, S.; Iodice, S.; Caini, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Fargnoli, M.C. MC1R variants, melanoma and red hair color phenotype: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 2753–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstenblith, M.R.; Shi, J.; Landi, M.T. Genome-wide association studies of pigmentation and skin cancer: A review and meta-analysis. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2010, 23, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, E.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Gandini, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Liu, F.; Kayser, M.; Nijsten, T.; Han, J.; Kumar, R.; Gruis, N.A.; et al. MC1R gene variants and non-melanoma skin cancer: A pooled-analysis from the M-SKIP project. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, M.T.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Tsang, S.; Gold, B.; Munroe, D.; Rebbeck, T.; Swoyer, J.; Ter-Minassian, M.; Hedayati, M.; Grossman, L.; et al. MC1R, ASIP, and DNA repair in sporadic and familial melanoma in a Mediterranean population. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, D.; Nagore, E.; Bermejo, J.L.; Figl, A.; Botella-Estrada, R.; Thirumaran, R.K.; Angelini, S.; Hemminki, K.; Schadendorf, D.; Kumar, R. Melanocortin receptor 1 variants and melanoma risk: A study of 2 European populations. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, C.; Parra, E.J.; Pfaff, C.L.; Dios, S.; Marshall, J.A.; Hamman, R.F.; Ferrell, R.E.; Hoggart, C.L.; McKeigue, P.M.; Shriver, M.D. Admixture in the Hispanics of the San Luis Valley, Colorado, and its implications for complex trait gene mapping. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2004, 68, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, M.; Edgar, H.; Mosley, C.; Hunley, K. Associations between ethnic identity, regional history, and genomic ancestry in New Mexicans of Spanish-speaking descent. Biodemography Soc. Biol. 2018, 64, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimentidis, Y.C.; Miller, G.F.; Shriver, M.D. Genetic admixture, self-reported ethnicity, self-estimated admixture, and skin pigmentation among Hispanics and Native Americans. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2009, 138, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanetsky, P.A.; Hay, J.L. Marshaling the Translational Potential of MC1R for Precision Risk Assessment of Melanoma. Cancer Prev. Res. 2018, 11, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V.M.; Shuk, E.; Arniella, G.; Gonzalez, C.J.; Gany, F.; Hamilton, J.G.; Gold, G.S.; Hay, J.L. A Qualitative Exploration of Latinos’ Perceptions about Skin Cancer: The Role of Gender and Linguistic Acculturation. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coups, E.J.; Stapleton, J.L.; Manne, S.L.; Hudson, S.V.; Medina-Forrester, A.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Gordon, M.; Tatum, K.S.; Robinson, J.K.; Natale-Pereira, A.; et al. Psychosocial correlates of sun protection behaviors among U.S. Hispanic adults. J. Behav. Med. 2014, 37, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.C.; Bruce, S.; Weinberg, A.D.; Cooper, H.P.; Yen, A.H.; Hill, M. Early detection of skin cancer: Racial/ethnic differences in behaviors and attitudes. J. Cancer Educ. 1994, 9, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Parmet, Y.; Allen, G.; Parker, D.F.; Ma, F.; Rouhani, P.; Kirsner, R.S. Disparity in melanoma: A trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch. Dermatol. 2009, 145, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, M.; Robinson, J.K.; Camara, C.; Chittineni, B.; Fisher, S.G. Skin cancer awareness in suburban employees: A Hispanic perspective. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 47, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.K.; Joshi, K.M.; Ortiz, S.; Kundu, R.V. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: Recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieser, M.J.; Wilson, S.; Vrieze, S. Behavioral impact of return of genetic test results for complex disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, A.; Vinson, C.A.; Chambers, D.A. Future directions for implementation science at the National Cancer Institute: Implementation Science Centers in Cancer Control. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 11, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C.; Clyne, M.; Kennedy, A.E.; Chambers, D.A.; Khoury, M.J. The current state of funded NIH grants in implementation science in genomic medicine: A portfolio analysis. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.L.; Berwick, M.; Zielaskowski, K.; White, K.A.; Rodriguez, V.M.; Robers, E.; Guest, D.D.; Sussman, A.; Talamantes, Y.; Schwartz, M.R.; et al. Implementing an Internet-Delivered Skin Cancer Genetic Testing Intervention to Improve Sun Protection Behavior in a Diverse Population: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc 2017, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, M.; Greenberg, E.; Jin, Y.; Paulsen, C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483); U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath, K.; Nagler, R.H.; Bigman-Galimore, C.A.; McCauley, M.P.; Jung, M.; Ramanadhan, S. The communications revolution and health inequalities in the 21st century: Implications for cancer control. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorence, D.; Park, H. Group disparities and health information: A study of online access for the underserved. Health Inform. J. 2008, 14, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorence, D.P.; Park, H.; Fox, S. Racial disparities in health information access: Resilience of the Digital Divide. J. Med. Syst. 2006, 30, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.J.; Manne, S.L.; Myers, R.E.; Keenan, E.M.; Balshem, A.M.; Weinberg, D.S. Predictors of patient uptake of colorectal cancer gene environment risk assessment. Genome Med. 2012, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, J.; Kaphingst, K.A.; Baser, R.; Li, Y.; Hensley-Alford, S.; McBride, C.M. Skin cancer concerns and genetic risk information-seeking in primary care. Public Health Genom. 2012, 15, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.L.; Meyer White, K.; Sussman, A.; Kaphingst, K.; Guest, D.; Schofield, E.; Dailey, Y.T.; Robers, E.; Schwartz, M.R.; Zielaskowski, K.; et al. Psychosocial and Cultural Determinants of Interest and Uptake of Skin Cancer Genetic Testing in Diverse Primary Care. Public Health Genom. 2019, 22, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; Khan, E.; White, K.M.; Sussman, A.; Guest, D.; Schofield, E.; Dailey, Y.T.; Robers, E.; Schwartz, M.R.; Li, Y.; et al. Effects of health literacy skills, educational attainment, and level of melanoma risk on responses to personalized genomic testing. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Anyone Can Get Skin Cancer; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; McBride, C.M.; Wade, C.; Alford, S.H.; Reid, R.; Larson, E.; Baxevanis, A.D.; Brody, L.C. Patients’ understanding of and responses to multiplex genetic susceptibility test results. Genet. Med. 2012, 14, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Yaroch, A.L.; Dancel, M.; Saraiya, M.; Crane, L.A.; Buller, D.B.; Manne, S.; O’Riordan, D.L.; Heckman, C.J.; Hay, J.; et al. Measures of sun exposure and sun protection practices for behavioral and epidemiologic research. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, C.; Trock, B.; Rimer, B.K.; Jepson, C.; Brody, D.; Boyce, A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychol. 1991, 10, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, L.D.; Griffin, J.M.; Partin, M.R.; Noorbaloochi, S.; Grill, J.P.; Snyder, A.; Bradley, K.A.; Nugent, S.M.; Baines, A.D.; Vanryn, M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, L.D.; Bradley, K.A.; Boyko, E.J. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam. Med. 2004, 36, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.E.; Kreps, G.L.; Hesse, B.W.; Croyle, R.T.; Willis, G.; Arora, N.K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K.V.; Weinstein, N.; Alden, S. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J. Behav. Med. 1982, 5, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.A.; Hay, J.L.; Orom, H.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Drake, B.F. “Don’t know” responses to risk perception measures: Implications for underserved populations. Med. Decis. Making 2013, 33, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, T.B. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch. Dermatol. 1988, 124, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, S.; Sera, F.; Cattaruzza, M.S.; Pasquini, P.; Abeni, D.; Boyle, P.; Melchi, C.F. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: I. Common and atypical naevi. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garamszegi, L.Z. Comparing effect sizes across variables: Generalization without the need for Bonferroni correction. Behav. Ecol. 2006, 17, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How Big is a Big Odds Ratio? Interpreting the Magnitudes of Odds Ratios in Epidemiological Studies. Commun. Stat.—Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.L.; Zielaskowski, K.; Meyer White, K.; Kaphingst, K.; Robers, E.; Guest, D.; Sussman, A.; Talamantes, Y.; Schwartz, M.; Rodriguez, V.M.; et al. Interest and Uptake of MC1R Testing for Melanoma Risk in a Diverse Primary Care Population: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.A.M.; Dailey, Y.T.; Guest, D.D.; Zielaskowski, K.; Robers, E.; Sussman, A.; Hunley, K.; Hughes, C.R.; Schwartz, M.R.; Kaphingst, K.A.; et al. MC1R Variation in a New Mexico Population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Yenter, D.; Chou, W.S.; Kaphingst, K.A. State of recent literature on communication about cancer genetic testing among Latinx populations. J. Genet. Couns 2020, 30, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, C.M.; Koehly, L.M.; Sanderson, S.C.; Kaphingst, K.A. The behavioral response to personalized genetic information: Will genetic risk profiles motivate individuals and families to choose more healthful behaviors? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloss, C.S.; Schork, N.J.; Topol, E.J. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.W.; Prentice-Dunn, S. Protection motivation theory. In Handbook of Health Behavior Research 1: Personal and Social Determinants; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.M.; Ding, H.; Guy, G.P., Jr.; Watson, M.; Hartman, A.M.; Perna, F.M. Prevalence of Sun Protection Use and Sunburn and Association of Demographic and Behaviorial Characteristics with Sunburn Among US Adults. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.L.; Shuk, E.; Schofield, E.; Loeb, R.; Holland, S.; Burkhalter, J.; Li, Y. Real-time sun protection decisions in first-degree relatives of melanoma patients. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Gies, P.; O’Riordan, D.L.; Elliott, T.; Nehl, E.; McCarty, F.; Davis, E. Validity of self-reported solar UVR exposure compared with objectively measured UVR exposure. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 3005–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, J.C.; Collins, F.S. Precision medicine in 2030-seven ways to transform healthcare. Cell 2021, 184, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.C.; Kennedy, A.E.; Chambers, D.A.; Khoury, M.J. The current state of implementation science in genomic medicine: Opportunities for improvement. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ethnicity, Hispanic | All, n (%) | Study Completers, n (%) | Lost-to-Follow-Up, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 286 (48%) | 220 (45%) | 66 (63%) | <0.01 | |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 15 (3%) | 12 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 0.11 |

| Asian | 12 (2%) | 10 (2%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Black or African American | 15 (3%) | 14 (3%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| White | 423 (71%) | 357 (72%) | 66 (62%) | |

| Other | 132 (22%) | 99 (20%) | 33 (31%) | |

| Gender, female | 473 (79%) | 390 (79%) | 83 (78%) | 0.88 |

| Education | ||||

| <HS | 46 (8%) | 28 (6%) | 18 (17%) | <0.01 |

| HS or GED | 94 (16%) | 66 (13%) | 28 (26%) | |

| Some college | 142 (24%) | 121 (24%) | 21 (20%) | |

| Associates degree or higher | 318 (53%) | 279 (56%) | 39 (37%) | |

| Income | ||||

| <USD 10,000 | 75 (13%) | 58 (12%) | 17 (17%) | <0.01 |

| USD 10,000–29,000 | 175 (31%) | 135 (29%) | 40 (40%) | |

| USD 30,000–49,000 | 97 (17%) | 82 (18%) | 15 (15%) | |

| USD 50,000–69,000 | 69 (12%) | 58 (12%) | 11 (11%) | |

| USD 70,000–89,000 | 49 (9%) | 44 (9%) | 5 (5%) | |

| ≥USD 90,000 | 102 (18%) | 90 (19%) | 12 (12%) | |

| Personal Cancer History, Yes | 95 (16%) | 75 (15%) | 20 (19%) | 0.36 |

| Family History of Skin Cancer, Yes | 202 (35%) | 181 (37%) | 21 (21%) | <0.01 |

| Don’t Know (abs. cont.) | 62 (10%) | 43 (9%) | 19 (18%) | <0.01 |

| Absolute dichotomous, likely | 191 (49%) | 169 (52%) | 22 (35%) | 0.02 |

| Don’t Know (abs. dich.) | 207 (35%) | 165 (33%) | 42 (40%) | 0.20 |

| Test Offer | 499 (83%) | 406 (82%) | 93 (88%) | 0.17 |

| Test Completion, acceptors 1 | 204 (41%) | 194 (48%) | 10 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Risk Feedback, higher risk 1 | 73 (60%) | 69 (60%) | 4 (67%) | 0.74 |

| Skin Cancer Screening, Ever | 223 (37%) | 186 (38%) | 37 (35%) | 0.57 |

| Mean (SD) | All, n (%) | Study Completers, n (%) | Lost-to-Follow-Up, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.84 (14.3) | 53.22 (14.0) | 56.71 (15.3) | 0.70 |

| Burnability | 0.48 (0.6) | 0.47 (0.6) | 0.53 (0.6) | 0.43 |

| Tannability | 0.83 (0.6) | 0.81 (0.5) | 0.89 (0.6) | 0.50 |

| Lifetime Number of Sunburns | 1.21 (1.2) | 1.25 (1.2) | 1.03 (1.3) | 0.10 |

| Health Literacy | 10.59 (2.1) | 10.73 (1.9) | 9.92 (2.8) | 0.19 |

| Importance of Genetic Testing, | 5.96 (1.5) | 5.97 (1.5) | 5.91 (1.7) | 0.69 |

| Perceived Risk | ||||

| Absolute continuous | 3.95 (1.4) | 4.00 (1.4) | 3.71 (1.7) | 0.31 |

| Comparative cont. | 2.87 (1.0) | 2.90 (0.9) | 2.72 (1.1) | 0.79 |

| Sun Protection | 17.07 (3.8) | 17.15 (3.8) | 16.69 (4.0) | 0.26 |

| Skin Cancer Worry | 2.54 (1.1) | 2.53 (1.0) | 2.58 (1.2) | 0.68 |

| Group | Model n | Sun Protection b (p) | Skin Cancer Screening OR (p) | Skin Cancer Worry b (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Offer (n = 406) vs. Usual Care (n = 87) | 493 | −0.12 (0.680) | 1.24 (0.546) | −0.01 (0.873) |

| Baseline | 0.68 (<0.001) | 2.24 (0.002) | 0.08 (0.001) | |

| Complete (n = 194) vs. Decline Testing (n = 211) | 405 | 0.36 (0.148) | 0.97 (0.903) | −0.02 (0.765) |

| Baseline | 0.68 (<0.001) | 2.06 (0.013) | 0.07 (0.008) | |

| Higher (n = 69) vs. Avg (n = 45) risk feedback | 114 | 0.35 (0.431) | 0.82 (0.710) | −0.01 (0.921) |

| Baseline | 0.71 (<0.001) | 1.88 (0.230) | 0.10 (0.045) |

| Moderator Variable | Sun Protection, η2 (p-Value) | Skin Exam, OR (p-Value) | Worry, η2 (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 0.00 (0.67) | 1.86 (0.62) | 0.00 (0.97) |

| Race: White | 0.00 (0.60) | 1.03 (>0.99) | 0.00 (0.96) |

| Gender | 0.00 (0.50) | 2.36 (0.55) | 0.00 (0.94) |

| Education | 0.00 (0.70) | 8.32 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.51) |

| Age | 0.00 (0.80) | 1.76 (0.39) | 0.01 (0.68) |

| Income | 0.00 (0.64) | 2.29 (0.44) | 0.00 (0.86) |

| Personal Cancer History | 0.01 (0.19) | 4.92 (0.18) | 0.01 (0.50) |

| Family History of Skin Cancer | 0.00 (0.62) | 16.65 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.79) |

| Burnability | 0.01 (0.16) | 1.34 (0.58) | 0.01 (0.56) |

| Tannability | 0.03 (0.01) | 1.32 (0.59) | 0.01 (0.65) |

| Lifetime number of sunburns | 0.00 (0.93) | 36.97 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.41) |

| Health Literacy | 0.00 (0.49) | 1.46 (0.62) | 0.00 (0.94) |

| Importance of Genetic Testing | 0.00 (0.61) | 2.97 (0.16) | 0.00 (0.71) |

| Perceived Risk | |||

| Absolute continuous | 0.01 (0.09) | 2.45 (0.13) | 0.00 (0.89) |

| DK (abs. cont.): DK response | 0.01 (0.09) | >99 (NaN) | 0.00 (>0.99) |

| Absolute dichotomous: Likely | 0.02 (0.04) | 1.83 (0.63) | 0.05 (0.20) |

| DK (abs. dich.): DK response | 0.00 (0.96) | 1.06 (0.96) | 0.01 (0.48) |

| Comparative cont. | 0.01 (0.11) | 2.09 (0.20) | 0.00 (0.99) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hay, J.L.; Kaphingst, K.A.; Buller, D.; Schofield, E.; Meyer White, K.; Sussman, A.; Guest, D.; Dailey, Y.T.; Robers, E.; Schwartz, M.R.; et al. Behavioral and Psychological Outcomes Associated with Skin Cancer Genetic Testing in Albuquerque Primary Care. Cancers 2021, 13, 4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164053

Hay JL, Kaphingst KA, Buller D, Schofield E, Meyer White K, Sussman A, Guest D, Dailey YT, Robers E, Schwartz MR, et al. Behavioral and Psychological Outcomes Associated with Skin Cancer Genetic Testing in Albuquerque Primary Care. Cancers. 2021; 13(16):4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164053

Chicago/Turabian StyleHay, Jennifer L., Kimberly A. Kaphingst, David Buller, Elizabeth Schofield, Kirsten Meyer White, Andrew Sussman, Dolores Guest, Yvonne T. Dailey, Erika Robers, Matthew R. Schwartz, and et al. 2021. "Behavioral and Psychological Outcomes Associated with Skin Cancer Genetic Testing in Albuquerque Primary Care" Cancers 13, no. 16: 4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164053

APA StyleHay, J. L., Kaphingst, K. A., Buller, D., Schofield, E., Meyer White, K., Sussman, A., Guest, D., Dailey, Y. T., Robers, E., Schwartz, M. R., Li, Y., Hunley, K., & Berwick, M. (2021). Behavioral and Psychological Outcomes Associated with Skin Cancer Genetic Testing in Albuquerque Primary Care. Cancers, 13(16), 4053. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164053