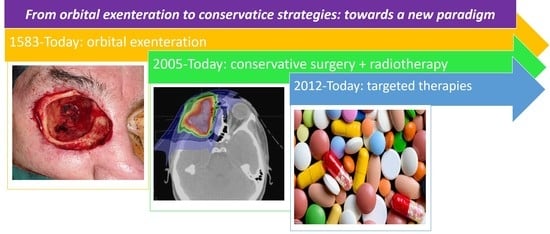

New Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours: Towards a New ‘Eye-Sparing’ Paradigm?

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method for Literature Search

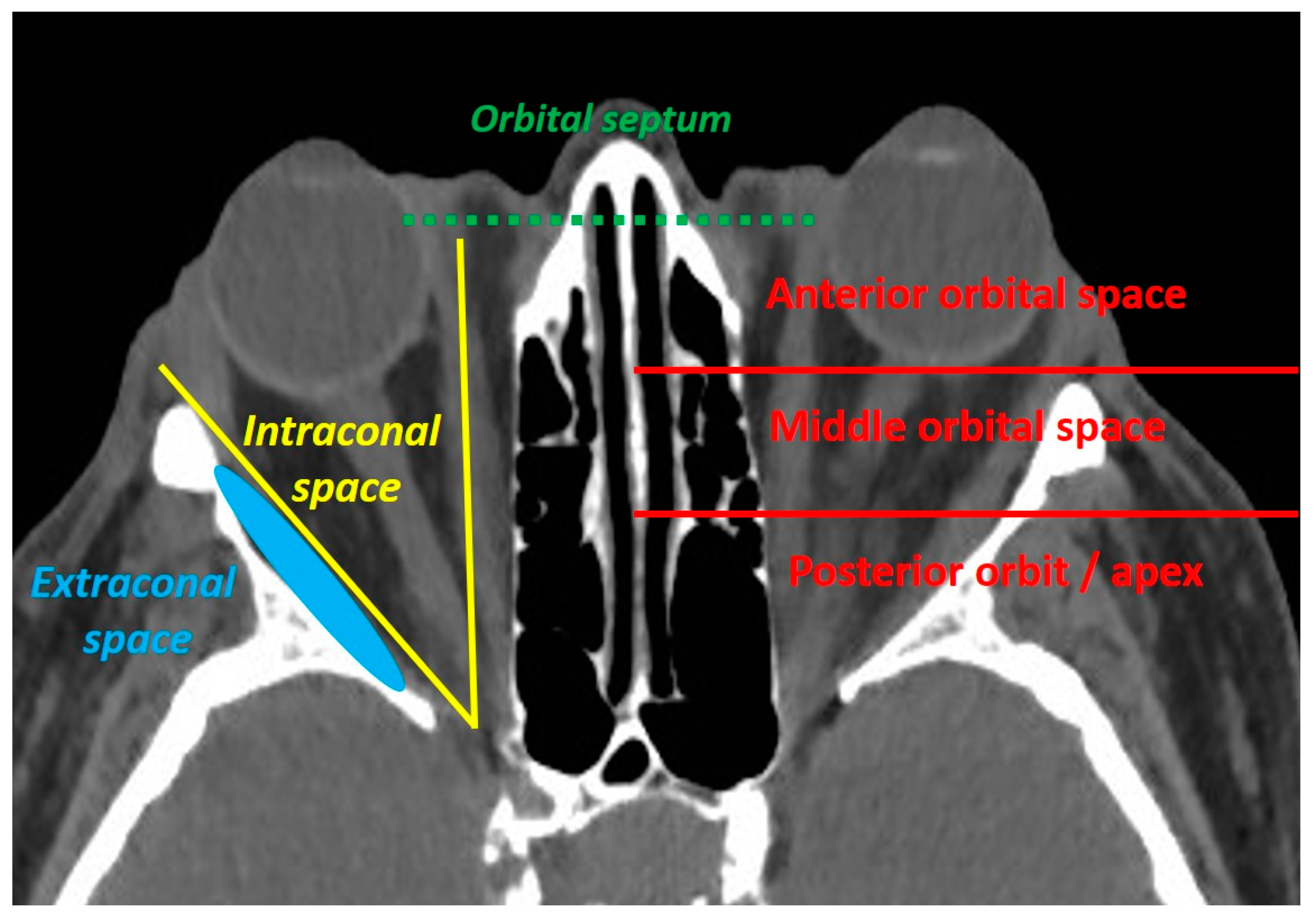

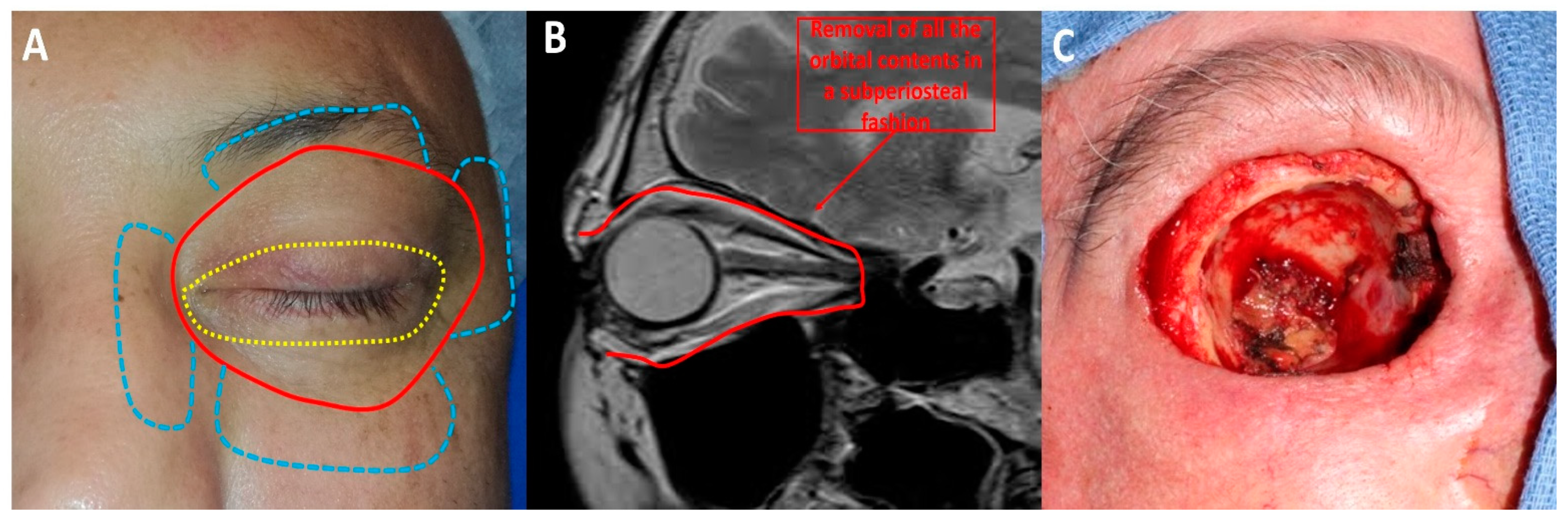

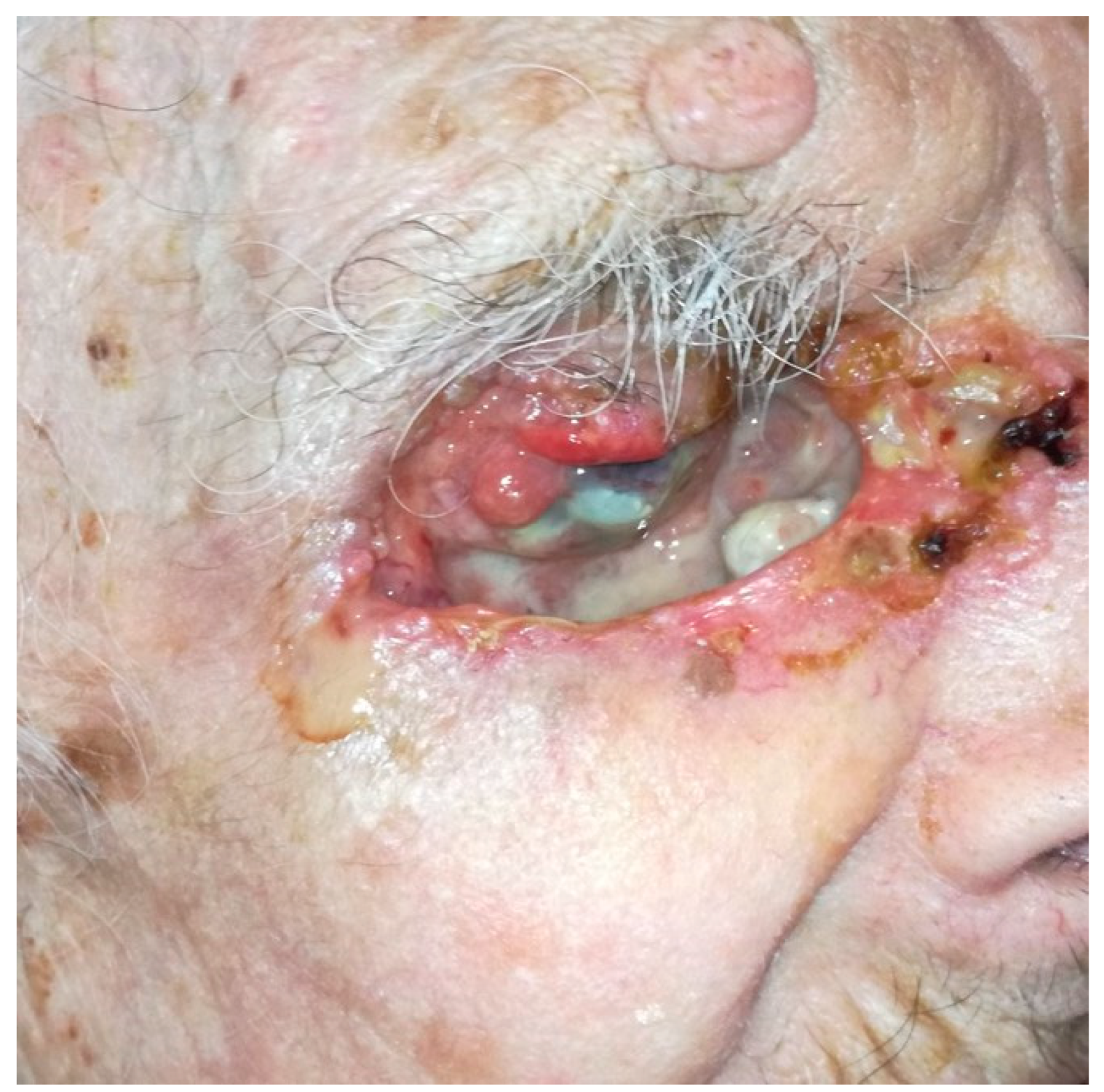

3. Orbital Exenteration for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours

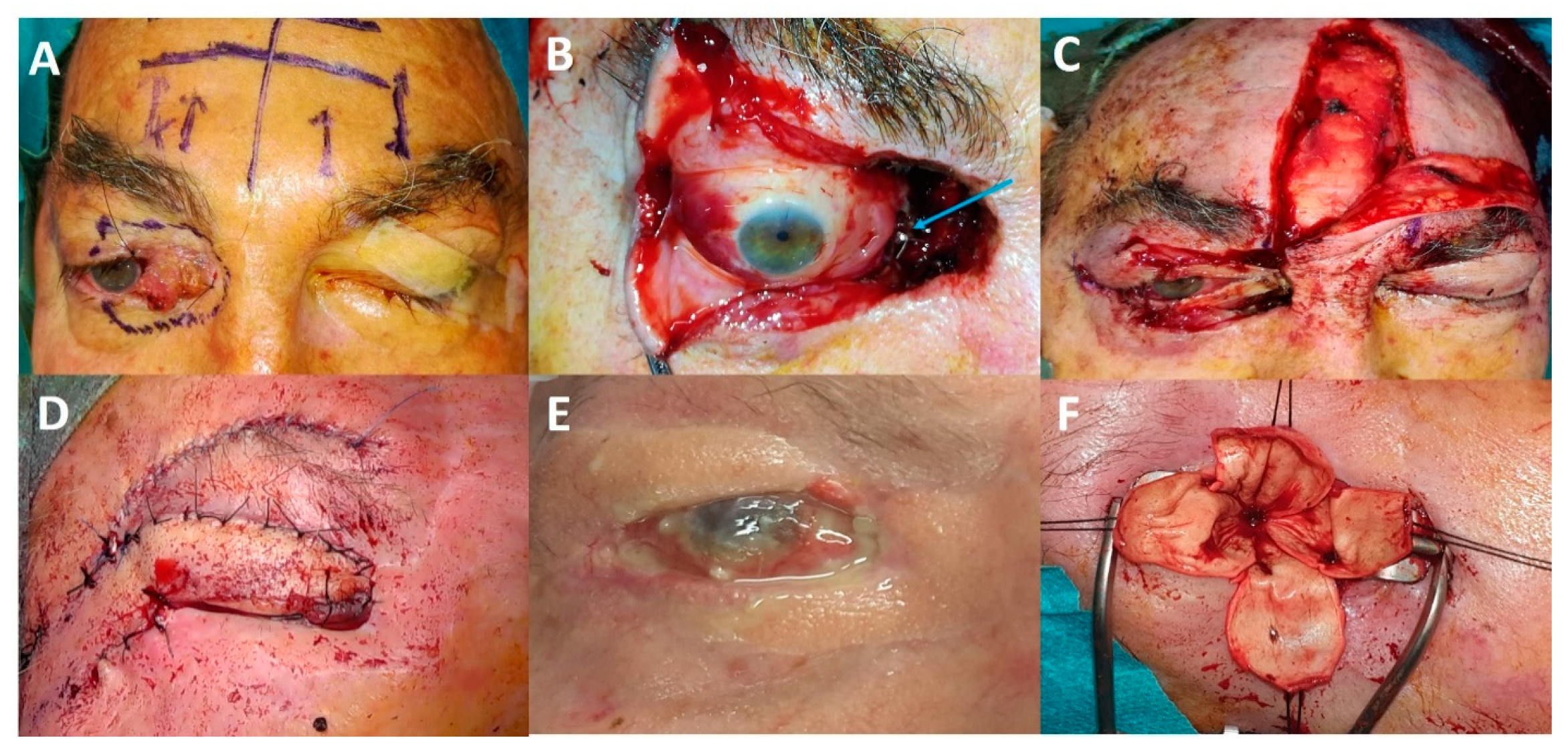

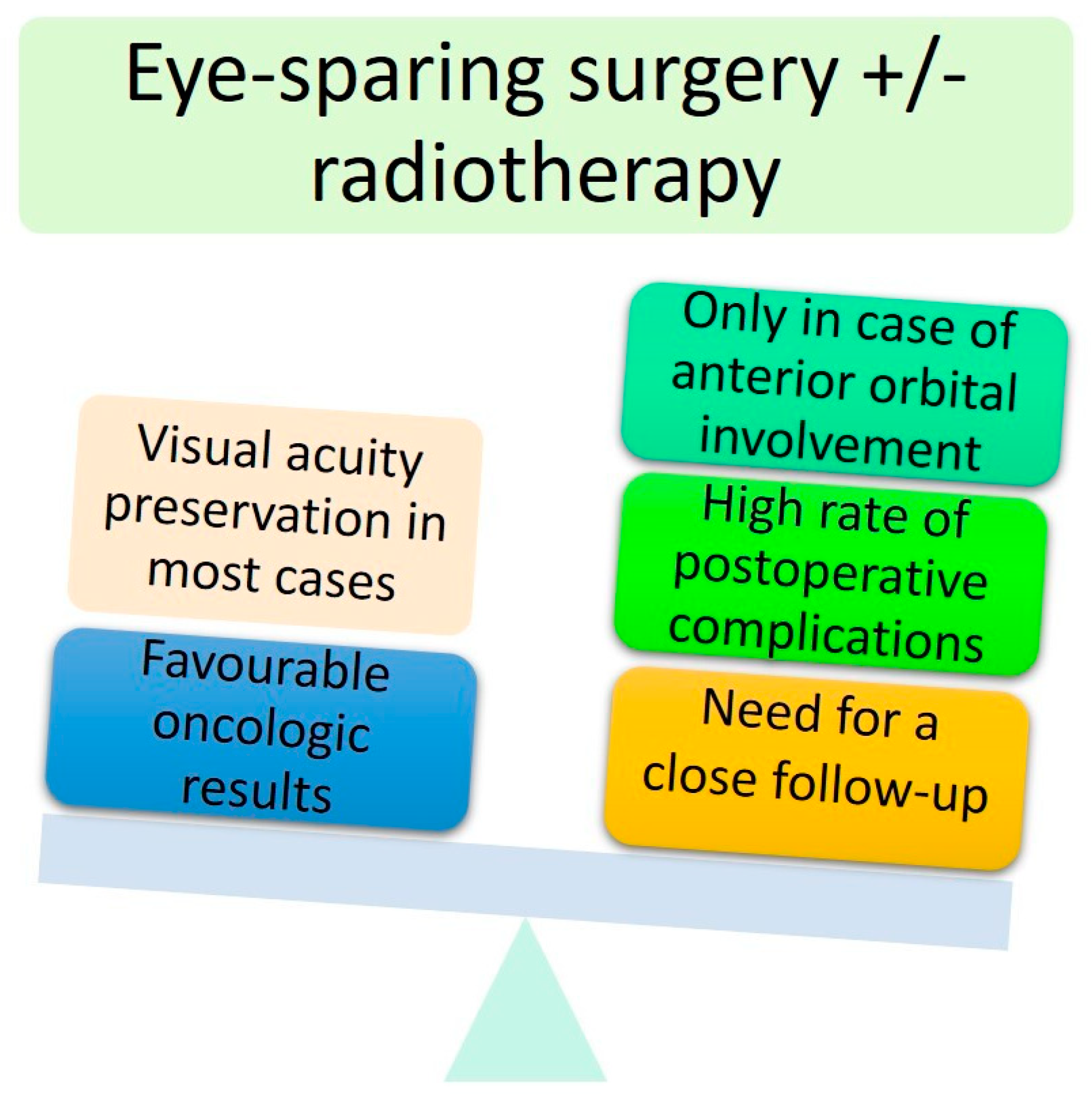

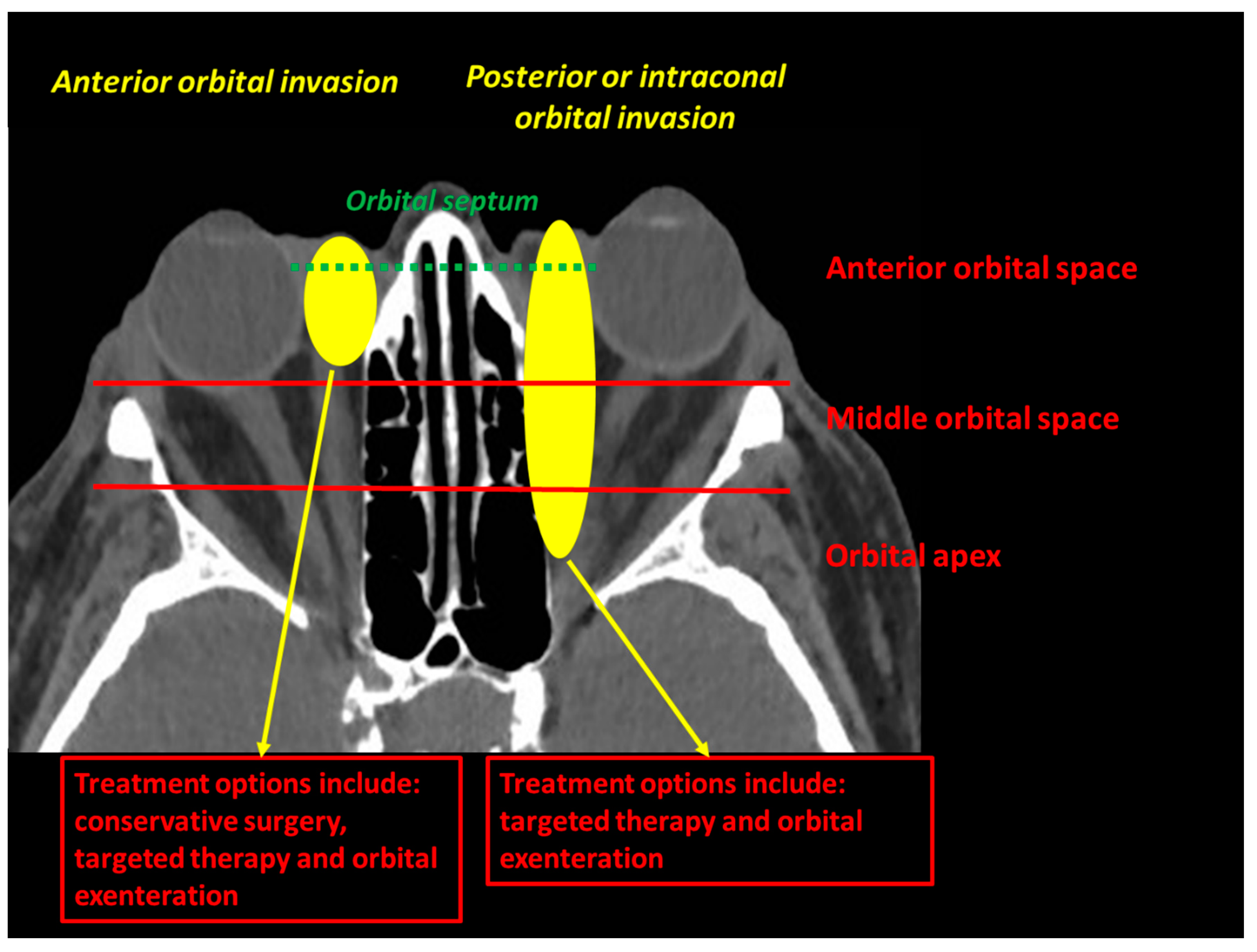

4. First Step towards Eye-Sparing Strategies: Conservative Surgery Followed or Not by Adjuvant Radiotherapy

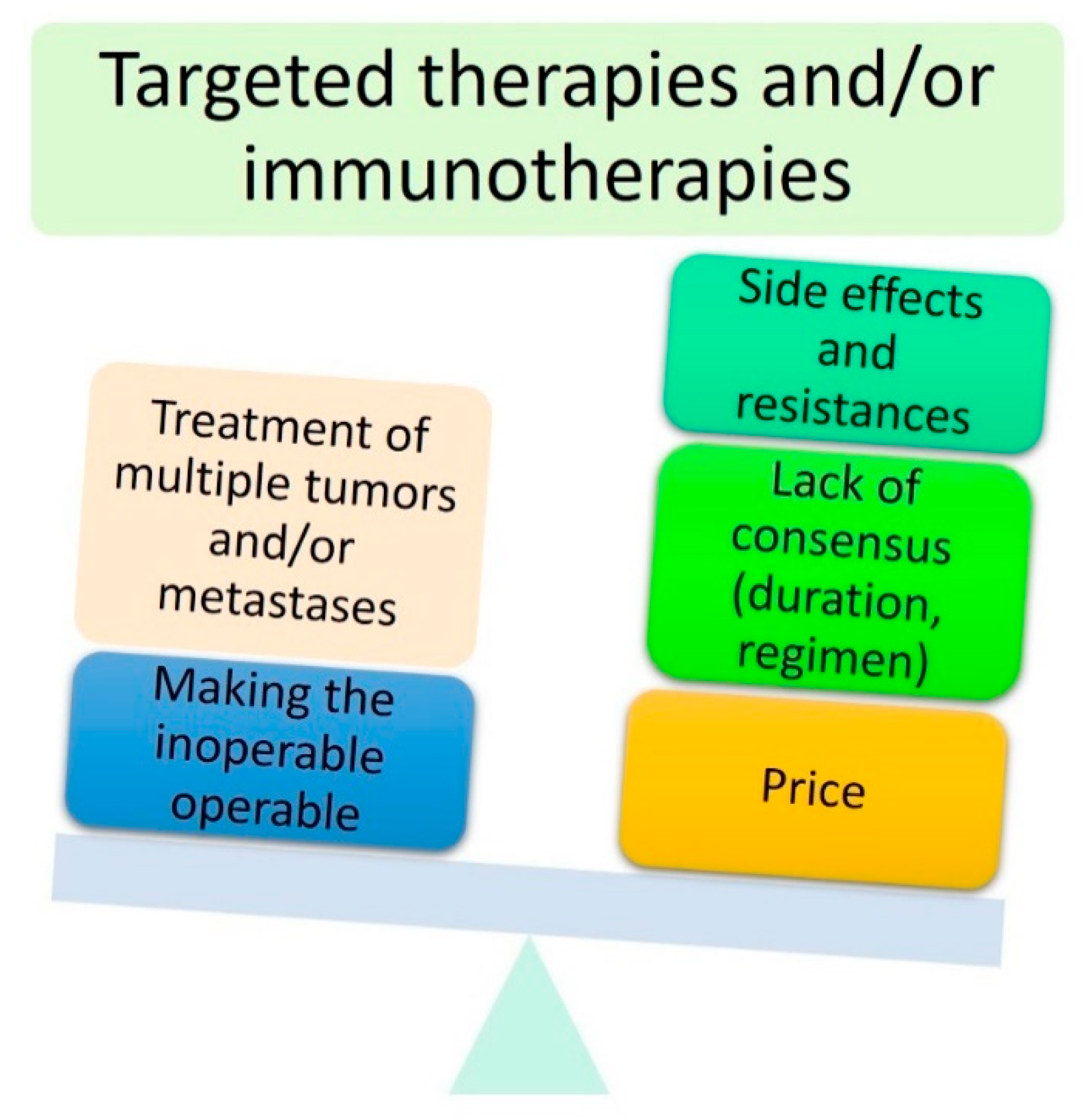

5. Second Step towards Eye-Sparing Strategies: Use of Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies

5.1. Targeted Therapies in Locally Advanced BCC: More Questions Than Answers?

- Between 58% and 75% of patients had an orbital involvement at the time of diagnosis. For these patients, anti-SMO therapies were prescribed to avoid OE. However, for the remaining patients without obvious orbital involvement, anti-SMO therapies were used to treat large eyelid tumours for which a wide surgical excision followed by multiple grafts and flaps would have otherwise been required. In addition, extended periocular reconstruction is often associated with residual eyelid malposition with subsequent exposure to keratitis [20]. Taken together, these data indicate that the term ‘locally advanced’ can be used for either eyelid tumours invading the orbit or eyelid tumours requiring complex and disfiguring periocular flaps and grafts.

- Treatment duration was not consensual and ranged from 2 to 53 months. This highlights the lack of consensus on treatment regimen (daily versus sequential administration) and exact duration. Sequential treatment with drug discontinuation during the weekend is currently under investigation.

- The rate of complete response was highly variable, ranging from 29% to 67%. This could be explained by the lack of clear guidelines for the definition of remission. Several studies were based on a clinical examination (mainly based on the RECIST criteria [15,17]), whereas other studies were based on a systematic surgical biopsy [16]. Of course, the histological analysis remains the gold standard, and the benefit/risk ratio and economic balance should be carefully considered for each patient.

- The large differences in the rates of patients undergoing adjuvant surgical excision (ranging from 4.7% to 100%) highlight two radically opposed treatment paradigms. Should anti-SMO therapies be considered a neoadjuvant treatment allowing surgeons to reduce perioperative surgical morbidity or a cure (i.e., treatment to be carried out until complete tumour removal)? The neoadjuvant paradigm would have several advantages such as reducing treatment duration (through reduced cost and treatment side effects) and systematic histopathological whole tumour control. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the use of anti-SMO therapies as an adjuvant treatment in the case of R1 or R2 periocular BCC resection.

- Anti-SMO side effects (i.e., alopecia, nausea, dysgeusia and muscle spasms) are known to be highly prevalent, affecting about 100% of patients. While they were often considered mild, drug discontinuation was needed in 7.7–38% of patients in periocular BCC studies. For these patients, systematically performing a biopsy after treatment should be discussed to ensure complete tumour removal. This high treatment discontinuation rate highlights the need to develop an alternative treatment regimen (discontinuation regimen). In addition, serious anti-SMO side effects should not be neglected. In their study involving 244 periocular BCCs, [19] found that 5.7% of patients died from anti–SMO-related side effects, whereas only 2% died from disease progression [19]. This finding should be kept in mind, especially in more fragile and elderly patients.

- Finally, the most meaningful data are probably the rate of secondary OE, ranging from 0% to 23%. As previously stated, the goal of anti-SMO therapies is eye preservation by avoiding OE. Unsurprisingly, this rate was higher in studies with a longer follow-up [15,18]. This result shows that anti-SMO therapies are not the ‘holy grail’.

5.2. Targeted Therapies Used for Other Periocular Malignant Tumours

5.3. Immunotherapies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kasaee, A.; Eshraghi, B.; Nekoozadeh, S.; Ameli, K.; Sadeghi, M.; Jamshidian-Tehrani, M. Orbital exenteration: A 23-year report. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 33, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibovitch, I.; McNab, A.; Sullivan, T.; Davis, G.; Selva, D. Orbital invasion by periocular basal cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madge, S.N.; Khine, A.A.; Thaller, V.T.; Davis, G.; Malhotra, R.; McNab, A.; O’Donnell, B.; Selva, D. Globe-Sparing surgery for medial canthal basal cell carcinoma with anterior orbital invasion. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 2222–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel, A.; Baillif, S.; Nahon-Esteve, S.; Gastaud, L.; Bertolotto, C.; Lassalle, S.; Lagier, J.; Hamedani, M.; Poissonnet, G. Orbital exenteration: An updated review with perspectives. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2021. (In Press, Corrected Proof). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, A.; Oberic, A.; Moulin, A.; Zografos, L.; Bellini, L.; Almairac, F.; Hamedani, M. Orbital exenteration and conjunctival melanoma: A 14-year study at the Jules Gonin eye hospital. Eye 2020, 34, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, R.A.; Kim, J.W.; Shorr, N. Orbital Exenteration: Results of an Individualized Approach. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 19, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, A.; Hamedani, M.; Lagier, J.; Bertolotto, C.; Gastaud, L.; Poissonnet, G. Does orbital exenteration still has a place in 2019? J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2019, 43, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackuaku-Dogbe, E.M.; Biritwum, R.B.; Briamah, Z.I. Psycho-social challenges of patients following orbital exenteration. East. Afr. Med. J. 2012, 89, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Martel, A.; Nahon-Esteve, S.; Gastaud, L.; Bertolotto, C.; Lassalle, S.; Baillif, S.; Charles, A. Incidence of orbital exenteration: A nationwide study in France over the 2006–2017 period. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavolontà, P.; Esmaeli, B.; Donna, P.; Tranfa, F.; Iuliano, A.; Abbate, V.; Fossataro, F.; Attanasi, F.; Bonavolontà, G. Outcomes after eye-sparing surgery vs orbital exenteration in patients with lacrimal gland carcinoma. Head Neck 2020, 42, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkow, N.; Jakobiec, F.A.; Lee, H.; Sutula, F.C. Long-Term outcomes of globe-preserving surgery with proton beam radiation for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 195, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.E.; Gore, S.K.; Plowman, N.P. Cranio-orbital resection does not appear to improve survival of patients with lacrimal gland carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 35, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Hu, J.; Gao, J.; Yang, J.; Qiu, X.; Kong, L.; Lu, J.J. Outcomes of orbital malignancies treated with eye-sparing surgery and adjuvant particle radiotherapy: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekulic, A.; Migden, M.R.; Oro, A.E.; Dirix, L.; Lewis, K.D.; Hainsworth, J.D.; Solomon, J.A.; Yoo, S.; Arron, S.T.; Friedlander, P.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2171–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, K.Y.; Fife, K.; Lear, J.T.; Price, R.D.; Durrani, A.J. Vismodegib for locally advanced periocular and orbital basal cell carcinoma: A review of 15 consecutive cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagiv, O.; Nagarajan, P.; Ferrarotto, R.; Kandl, T.J.; Thakar, S.D.; Glisson, B.S.; Altan, M.; Esmaeli, B. Ocular preservation with neoadjuvant vismodegib in patients with locally advanced periocular basal cell carcinoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 103, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiger-Moscovich, M.; Reich, E.; Tauber, G.; Berliner, O.; Priel, A.; Ben Simon, G.; Elkader, A.A.; Yassur, I. Efficacy of vismodegib for the treatment of orbital and advanced periocular basal cell carcinoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 207, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliphant, H.; Laybourne, J.; Chan, K.; Haridas, A.; Edmunds, M.R.; Morris, D.; Clarke, L.; Althaus, M.; Norris, P.; Cranstoun, M.; et al. Vismodegib for periocular basal cell carcinoma: An international multicentre case series. Eye 2020, 34, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ishai, M.; Tiosano, A.; Fenig, E.; Ben Simon, G.; Yassur, I. Outcomes of Vismodegib for periocular locally advanced basal cell carcinoma from an open-label trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020, 138, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verity, D.H.; Collin, J.R.O. Eyelid reconstruction: The state of the art. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 12, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastefanou, V.P.; René, C. Secondary resistance to Vismodegib after initial successful treatment of extensive recurrent periocular basal cell carcinoma with orbital invasion. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 33, S68–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, J.E.; Basset-Séguin, N. Vismodegib: A Review in advanced basal cell carcinoma. Drugs 2018, 78, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-K.; Liao, S.-L.; Jou, J.-R.; Lai, P.-C.; Kao, S.C.S.; Hou, P.-K.; Chen, M.-S. Malignant eyelid tumours in taiwan. Eye 2003, 17, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, R.C. Molecularly targeted agents in oculoplastic surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, V.T.; Pfeiffer, M.L.; Esmaeli, B. Targeted therapy for orbital and periocular basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 29, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El-Sawy, T.; Sabichi, A.L.; Myers, J.N.; Kies, M.S.; William, W.N.; Glisson, B.S.; Lippman, S.; Esmaeli, B. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors for treatment of orbital squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2012, 130, 1608–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pasquali, S.; Hadjinicolaou, A.V.; Chiarion Sileni, V.; Rossi, C.R.; Mocellin, S. Systemic Treatments for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD011123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiani, C.; Béranger, G.E.; Leclerc, J.; Ballotti, R.; Bertolotto, C. Focus on cutaneous and uveal melanoma specificities. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 724–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, A.-C.; Dahl, C.; Dahmcke, C.M.; Lade-Keller, J.; Siersma, V.D.; Toft, P.B.; Coupland, S.E.; Prause, J.U.; Guldberg, P.; Heegaard, S. BRAF Mutations in conjunctival melanoma: Investigation of incidence, clinicopathological features, prognosis and paired premalignant lesions. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016, 94, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholz, S.L.; Cosgarea, I.; Süßkind, D.; Murali, R.; Möller, I.; Reis, H.; Leonardelli, S.; Schilling, B.; Schimming, T.; Hadaschik, E.; et al. NF1 Mutations in Conjunctival melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.L.; Smalley, K.S.; Sondak, V.K.; Gibney, G.T. Conjunctival Melanomas Harbor BRAF and NRAS Mutations—Letter. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24166902/ (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Kim, J.M.; Weiss, S.; Sinard, J.H.; Pointdujour-Lim, R. Dabrafenib and trametinib for BRAF-mutated conjunctival melanoma. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2020, 6, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagi Glass, L.R.; Lawrence, D.P.; Jakobiec, F.A.; Freitag, S.K. Conjunctival melanoma responsive to combined systemic BRAF/MEK inhibitors. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017, 33, e114–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Hu, C.; Shu, L.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, L.; Pu, X.; Wu, F. Clinical treatment options for early-stage and advanced conjunctival melanoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 66, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.L.; Kibbi, N.; Worley, B.; Kelm, R.C.; Wang, J.V.; Barker, C.A.; Behshad, R.; Bichakjian, C.K.; Bolotin, D.; Bordeaux, J.S.; et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e699–e714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladen, J.C.; Moosajee, M.; Tracey-White, D.; Beaconsfield, M.; O’Toole, E.A.; Philpott, M.P. Analysis of hedgehog signaling in periocular sebaceous carcinoma. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwon, M.J.; Shin, H.S.; Nam, E.S.; Cho, S.J.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, S.; Park, H.-R. Comparison of HER2 gene amplification and KRAS alteration in eyelid sebaceous carcinomas with that in other eyelid tumors. Pathol Res. Pr. 2015, 211, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, M.T.; Singh, R.R.; Seviour, E.G.; Curry, J.L.; Hudgens, C.W.; Bell, D.; Wimmer, D.A.; Ning, J.; Czerniak, B.A.; Zhang, L.; et al. Next-generation sequencing identifies high frequency of mutations in potentially clinically actionable genes in sebaceous carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2016, 240, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, V.S.; Habib, L.A.; Yoon, M.K. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: A review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2019, 64, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.D.; Sandhu, S.; Gyorki, D.E.; Johnston, M.L.; Rischin, D. Recent insights and advances in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Oncol. Pr. 2016, 12, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, L.A.; Wolkow, N.; Freitag, S.K.; Yoon, M.K. Advances in immunotherapy and periocular malignancy. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 34, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassalle, S.; Nahon-Esteve, S.; Frouin, E.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Josselin, N.; Cassoux, N.; Barnhill, R.; Scheller, B.; Baillif, S.; Hofman, P. PD-L1 expression in 65 conjunctival melanomas and its association with clinical outcome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, O.; Thakar, S.D.; Kandl, T.J.; Ford, J.; Sniegowski, M.C.; Hwu, W.-J.; Esmaeli, B. Immunotherapy with programmed cell death 1 inhibitors for 5 patients with conjunctival melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018, 136, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, P.T.; Pavlick, A.C. Checkpoint Inhibition immunotherapy for advanced local and systemic conjunctival melanoma: A clinical case series. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Migden, M.R.; Rischin, D.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; Lewis, K.D.; Chung, C.H.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Lim, A.M.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Conger, J.R.; Grob, S.R.; Tao, J. Massive periocular squamous cell carcinoma with response to pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 35, e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Russell, J.; Hamid, O.; Bhatia, S.; Terheyden, P.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Shih, K.C.; Lebbé, C.; Linette, G.P.; Milella, M.; et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic merkel cell carcinoma: A multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayaraj, P.; Sen, S. Evaluation of PD-L1 and PD-1 expression in aggressive eyelid sebaceous gland carcinoma and its clinical significance. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 1983–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yu, H.; Fu, G.; Fan, X.; Jia, R. Programmed death receptor ligand 1 expression in eyelid sebaceous carcinoma: A Consecutive case series of 41 patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019, 97, e390–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Musibay, E.; Murugan, P.; Giubellino, A.; Sharma, S.; Steinberger, D.; Yuan, J.; Hunt, M.A.; Lou, E.; Miller, J.S. Near Complete response to pembrolizumab in microsatellite-stable metastatic sebaceous carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Number of Patients | Number (%) of Patients with Orbital Involvement | Mean (Range) Treatment Duration (Months) | Number (%) of Patients Achieving a Complete Response | Number (%) of Patients Achieving an Incomplete Response | Number (%) of Patients with a Progressive Disease | Number (%) of Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Surgical Excision | Number (%) of Patients Undergoing Secondary Orbital Exenteration | Number (%) of Patients Who Discontinued Treatment Due to Excessive Side Effects (%) | Mean (Range) Follow-Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wong, 2015 [15] | 15 | 10 (67) | 13 (2–40) | 10 (67) | 3 (20) | 2 (13) | 1 (7) | 3 (20) | 5 (33) | 36 (14–52) |

| Sagiv, 2018 [16] | 8 | 6 (75) | 14 * (4–36) | 5 (62.5) † | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 18 (6–43) |

| Eiger-Moscovich, 2019 [17] | 21 | 15 (71.5) | 9 * (1–53) | 10 (48) | 11 (52) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.7) | 1 (4.7) | 8 (38) | 26 * (9–60) |

| Oliphant, 2020 [18] | 13 | 7 (58) | 7 (2–36) | 5 (38) | 8 (54) | 0 (0) | 6 (46) | 3 (23) | 1 (7.7) | 30 (12–48) |

| Ben Ishai, 2020 [19] | 244 ‡ | NR | 10 * (5–19.5) | 70 (28.7) | 94 (38.5) | 5 (2) | NR | NR | 58 (23.8) | 10 * (5.7–14) |

| Tumour Histology | Main Molecular Target |

|---|---|

| BCC | Hedgehog pathway (SMO) |

| SCC | EGFR PD-1/PD-L1 |

| Melanoma (lid or conjunctiva) | BRAF PD-1/PD-L1 CTLA4 |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | Hedgehog pathway HER2 Pi3K pathway PD-1/PD-L1 |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | AKT-mTOR pathway PD-1/PD-L1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martel, A.; Lassalle, S.; Picard-Gauci, A.; Gastaud, L.; Montaudie, H.; Bertolotto, C.; Nahon-Esteve, S.; Poissonnet, G.; Hofman, P.; Baillif, S. New Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours: Towards a New ‘Eye-Sparing’ Paradigm? Cancers 2021, 13, 2822. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112822

Martel A, Lassalle S, Picard-Gauci A, Gastaud L, Montaudie H, Bertolotto C, Nahon-Esteve S, Poissonnet G, Hofman P, Baillif S. New Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours: Towards a New ‘Eye-Sparing’ Paradigm? Cancers. 2021; 13(11):2822. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112822

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartel, Arnaud, Sandra Lassalle, Alexandra Picard-Gauci, Lauris Gastaud, Henri Montaudie, Corine Bertolotto, Sacha Nahon-Esteve, Gilles Poissonnet, Paul Hofman, and Stephanie Baillif. 2021. "New Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours: Towards a New ‘Eye-Sparing’ Paradigm?" Cancers 13, no. 11: 2822. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112822

APA StyleMartel, A., Lassalle, S., Picard-Gauci, A., Gastaud, L., Montaudie, H., Bertolotto, C., Nahon-Esteve, S., Poissonnet, G., Hofman, P., & Baillif, S. (2021). New Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours: Towards a New ‘Eye-Sparing’ Paradigm? Cancers, 13(11), 2822. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112822