Making Patient-Specific Treatment Decisions Using Prognostic Variables and Utilities of Clinical Outcomes

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Statistical Estimation

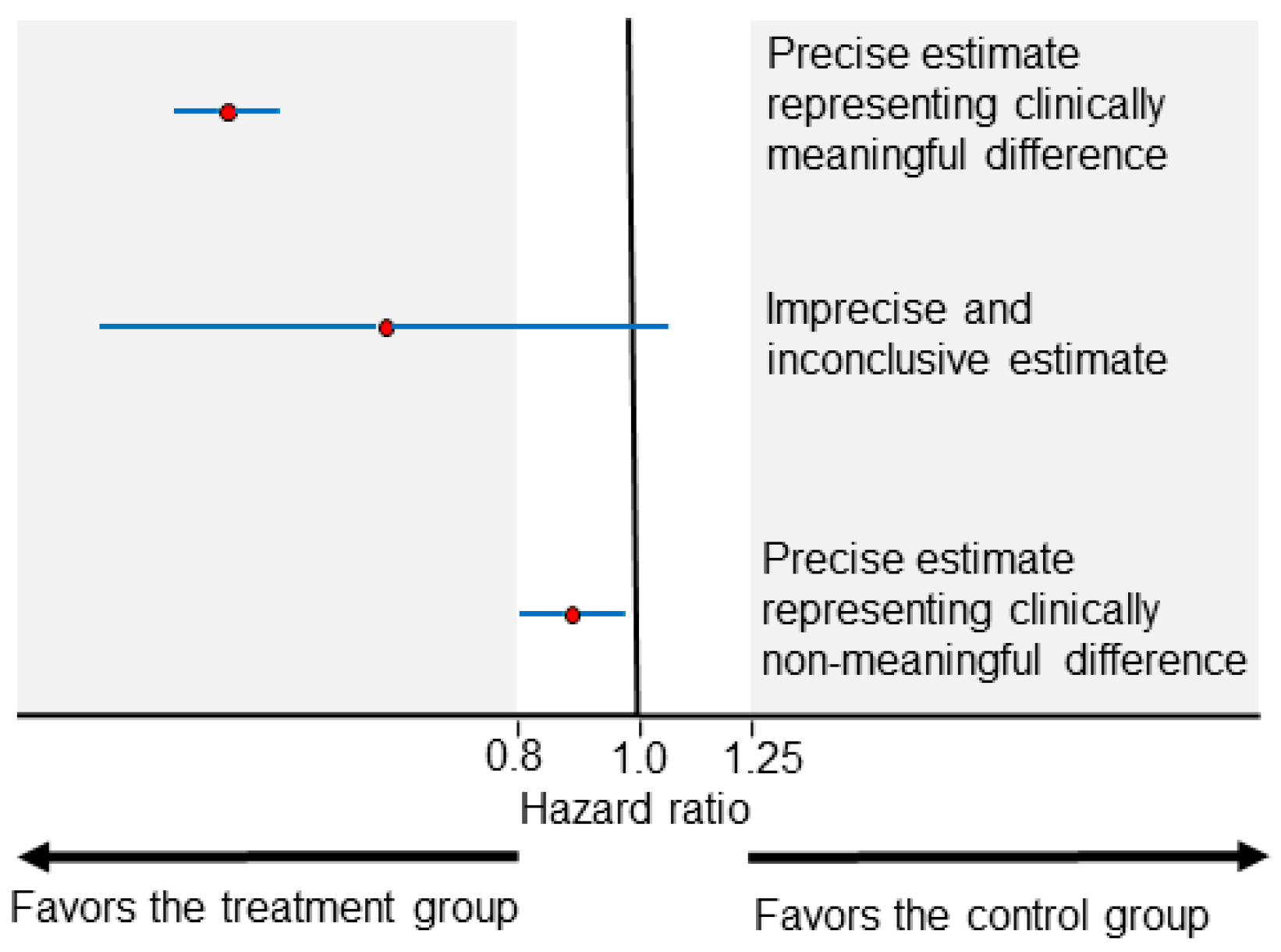

2.1. Advantages and Limitations of Estimated Parameters

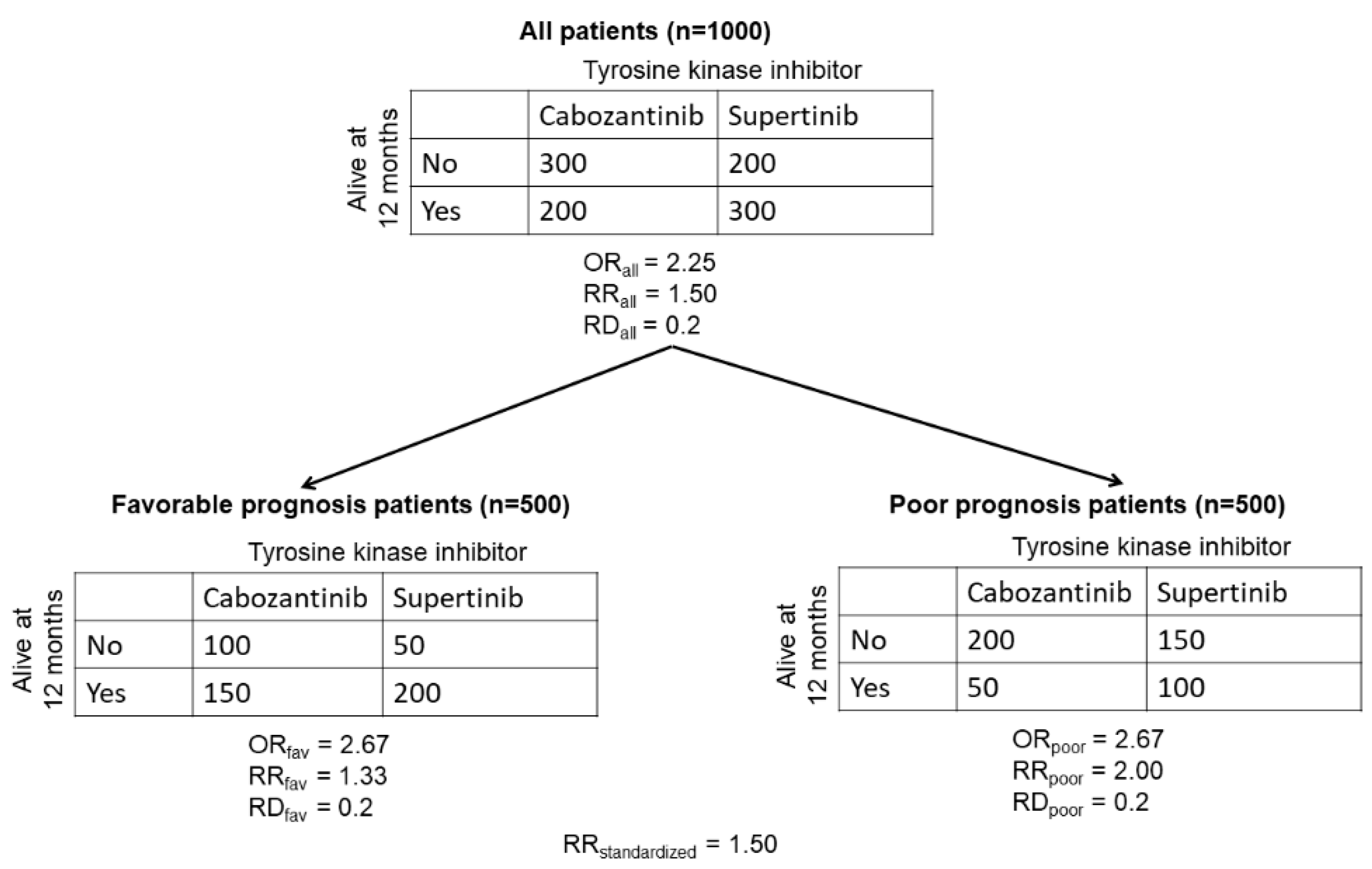

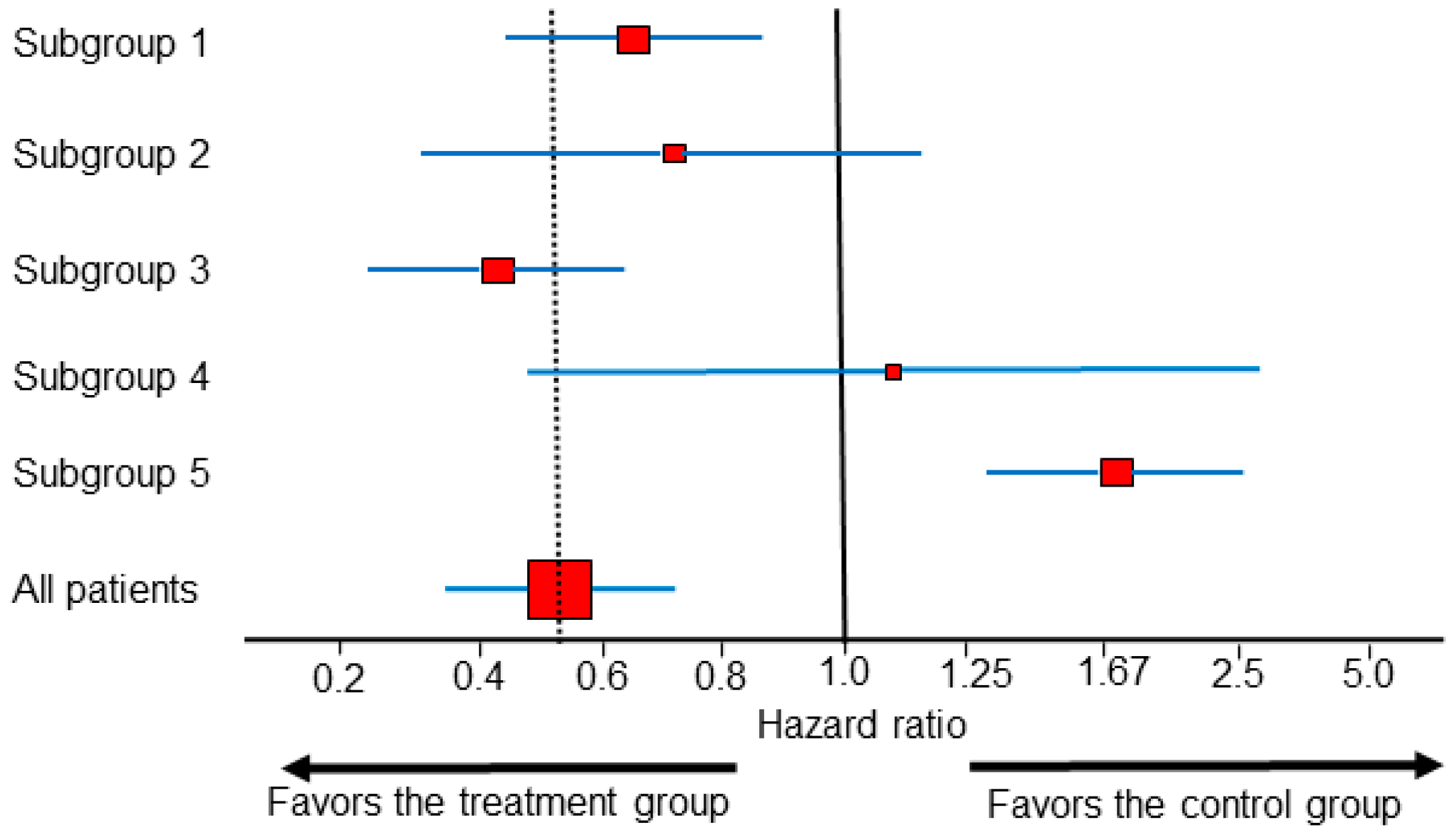

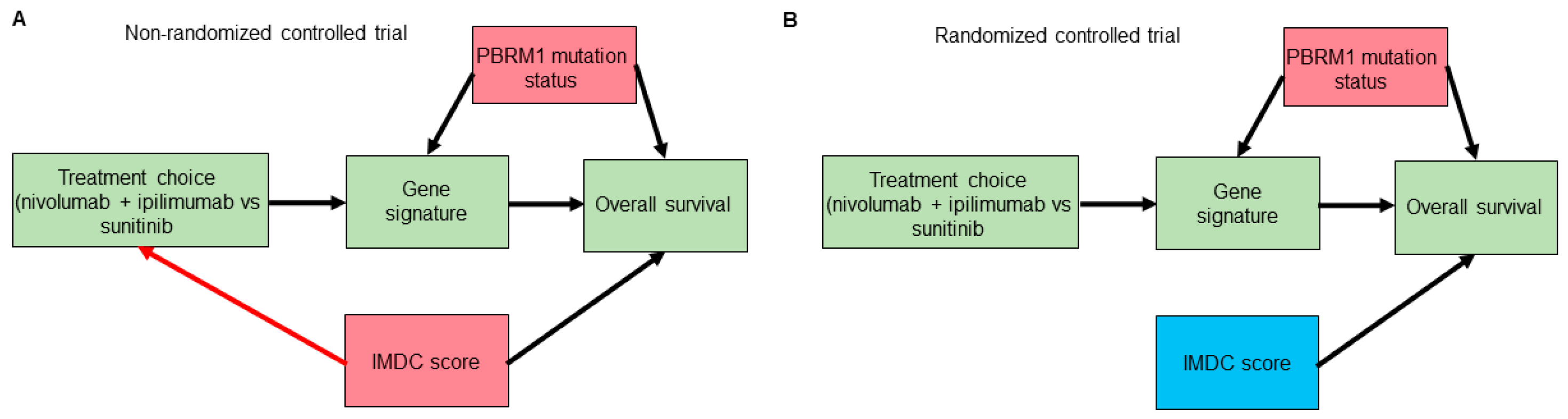

2.2. Subgroup Analysis on the Estimation Scale

3. Clinical Outcome Prediction

4. Making Clinical Decisions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Liu, K.; Meng, X.-L. There Is Individualized Treatment. Why Not Individualized Inference? Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 2016, 3, 79–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adashek, J.J.; Genovese, G.; Tannir, N.M.; Msaouel, P. Recent advancements in the treatment of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A review of the evidence using second-generation p-values. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2020, 23, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, D.Y.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Harshman, L.C.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Mackenzie, M.; Wood, L.; Donskov, F.; Tan, M.H.; et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Kidney Cancer (Version 1.2021). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Heng, D.Y.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Warren, M.A.; Golshayan, A.R.; Sahi, C.; Eigl, B.J.; Ruether, J.D.; Cheng, T.; North, S.; et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: Results from a large, multicenter study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5794–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.J.; Xie, W.; Kroeger, N.; Lee, J.L.; Rini, B.I.; Knox, J.J.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Srinivas, S.; Pal, S.K.; Yuasa, T.; et al. The International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium model as a prognostic tool in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma previously treated with first-line targeted therapy: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, S. Mastering variation: Variance components and personalised medicine. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 966–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, S. Seven myths of randomisation in clinical trials. Stat. Med. 2013, 32, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, J.F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, S. Statistical Issues in Drug Development, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. xix. 498p. [Google Scholar]

- Sutradhar, R.; Austin, P.C. Relative rates not relative risks: Addressing a widespread misinterpretation of hazard ratios. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, R.D.; Hoekstra, R.; Rouder, J.N.; Lee, M.D.; Wagenmakers, E.J. The fallacy of placing confidence in confidence intervals. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2016, 23, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, Z.; Greenland, S. Semantic and cognitive tools to aid statistical science: Replace confidence and significance by compatibility and surprise. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thall, P.F. Statistical Remedies for Medical Researchers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wolkewitz, M.; Beyersmann, J.; Gastmeier, P.; Schumacher, M. Modeling the effect of time-dependent exposure on intensive care unit mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2009, 35, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Mansournia, M.A. Limitations of individual causal models, causal graphs, and ignorability assumptions, as illustrated by random confounding and design unfaithfulness. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 30, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, R.; Zhang, J.; Farewell, D. Making apples from oranges: Comparing noncollapsible effect estimators and their standard errors after adjustment for different covariate sets. Biom. J. 2021, 63, 528–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didelez, V.; Stensrud, M.J. On the logic of collapsibility for causal effect measures. Biom. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansournia, M.A.; Greenland, S. The relation of collapsibility and confounding to faithfulness and stability. Epidemiology 2015, 26, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernan, M.A.; Clayton, D.; Keiding, N. The Simpson’s paradox unraveled. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenland, S.; Pearl, J.; Robins, J.M. Confounding and Collapsibility in Causal Inference. Stat. Sci. 1999, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, S.A.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Xu, C.; Lin, L.; Chivese, T.; Thalib, L. Questionable utility of the relative risk in clinical research: A call for change to practice. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernan, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Causal Inference; Taylor & Francis: Milton, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland, S. Smoothing Observational Data: A Philosophy and Implementation for the Health Sciences. Int. Stat. Rev. 2006, 74, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, P.L.; Gedye, C.; Boutros, P.C.; Wheatley-Price, P.; John, T. Current and Evolving Methods to Visualize Biological Data in Cancer Research. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, djw031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J. Forest plots and the interpretation of subgroups. Lancet 2005, 365, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Aren Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthelemy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Zurawski, B.; Oyervides Juarez, V.M.; Hsieh, J.J.; Basso, U.; Shah, A.Y.; et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grunwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Kopyltsov, E.; Mendez-Vidal, M.J.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulieres, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Penkov, K.; Haanen, J.; Rini, B.; Albiges, L.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Negrier, S.; Uemura, M.; et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Motzer, R.J.; Rini, B.I.; Haanen, J.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Gravis-Mescam, G.; Uemura, M.; Lee, J.L.; et al. Updated efficacy results from the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial: First-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, M.R.; James, N.D.; Sydes, M.R. ‘Thursday’s child has far to go’-interpreting subgroups and the STAMPEDE trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2327–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Agoritsas, T.; Alba, A.C.; Guyatt, G. How to use a subgroup analysis: Users’ guide to the medical literature. JAMA 2014, 311, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Briel, M.; Walter, S.D.; Guyatt, G.H. Is a subgroup effect believable? Updating criteria to evaluate the credibility of subgroup analyses. BMJ 2010, 340, c117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J.; Vehtari, A. Regression and Other Stories; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, D.M.; Paulus, J.K.; van Klaveren, D.; D’Agostino, R.; Goodman, S.; Hayward, R.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Patrick-Lake, B.; Morton, S.; Pencina, M.; et al. The Predictive Approaches to Treatment effect Heterogeneity (PATH) Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, D.M.; Steyerberg, E.; van Klaveren, D. Personalized evidence based medicine: Predictive approaches to heterogeneous treatment effects. BMJ 2018, 363, k4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, A.; Garrido-Castro, A.; Poorvu, P.; Winer, E.; Mittendorf, E.; King, T. Utility of the 21-Gene Recurrence Score in Node-Positive Breast Cancer. Oncology 2021, 35, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.; Emsley, R.; Liu, H.; Landau, S. Integrating biomarker information within trials to evaluate treatment mechanisms and efficacy for personalised medicine. Clin. Trials 2013, 10, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, D.D.; Msaouel, P. Causal Diagram Techniques for Urologic Oncology Research. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenland, S.; Pearl, J.; Robins, J.M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. xvi. 384p. [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas, J. Molecular genetics of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, J.J.; Chen, D.; Wang, P.I.; Marker, M.; Redzematovic, A.; Chen, Y.B.; Selcuklu, S.D.; Weinhold, N.; Bouvier, N.; Huberman, K.H.; et al. Genomic Biomarkers of a Randomized Trial Comparing First-line Everolimus and Sunitinib in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kim, T.B.; Peng, B.; Karam, J.; Creighton, C.; Joon, A.; Kawakami, F.; Trevisan, P.; Jonasch, E.; Chow, C.W.; et al. Sarcomatoid Renal Cell Carcinoma Has a Distinct Molecular Pathogenesis, Driver Mutation Profile, and Transcriptional Landscape. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 6686–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, C.; Forney, A.; Pearl, J. A Crash Course in Good and Bad Controls. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3689437 (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Snapinn, S.; Jiang, Q. On the clinical meaningfulness of a treatment’s effect on a time-to-event variable. Stat. Med. 2011, 30, 2341–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupacis, A.; Sackett, D.L.; Roberts, R.S. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 1728–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.L. Number needed to treat and number needed to harm are not the best way to report and assess the results of randomised clinical trials. Br. J. Haematol 2009, 146, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.L. Misleading Statistics. Pharm. Med. 2010, 24, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, L.J.; Publications, D. The Foundations of Statistics; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreia-Vioglio, S.; Maccheroni, F.; Marinacci, M.; Montrucchio, L. Classical subjective expected utility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6754–6759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, L.; Berger, N.; Bosetti, V.; Gilboa, I.; Hansen, L.P.; Jarvis, C.; Marinacci, M.; Smith, R.D. Rational policymaking during a pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, J.M.; Eraker, S.A. Parametric models of the utility of survival duration: Tests of axioms in a generic utility framework. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 44, 166–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G.J. The Development of Utility Theory. I. J. Political Econ. 1950, 58, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsert, J.; Kaliszyk, C. Towards Formal Foundations for Game Theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Theorem Proving (ITP 2018), Oxford, UK, 9–12 July 2018; pp. 495–503. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, T.A.; Thall, P.F.; Yuan, Y.; McAvoy, S.; Gomez, D.R. Robust treatment comparison based on utilities of semi-competing risks in non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2017, 112, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, T.A.; Yuan, Y.; Thall, P.F.; Elizondo, J.H.; Hofstetter, W.L. A utility-based design for randomized comparative trials with ordinal outcomes and prognostic subgroups. Biometrics 2018, 74, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thall, P.F.; Nguyen, H.Q. Adaptive randomization to improve utility-based dose-finding with bivariate ordinal outcomes. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2012, 22, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Thall, P.F.; Ji, Y.; Muller, P. Bayesian Dose-Finding in Two Treatment Cycles Based on the Joint Utility of Efficacy and Toxicity. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2015, 110, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, B.P.; Thall, P.F.; Lin, S.H. Bayesian Group Sequential Clinical Trial Design using Total Toxicity Burden and Progression-Free Survival. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2016, 65, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Thall, P.F.; Muller, P.; Mehran, R.J. A Decision-Theoretic Comparison of Treatments to Resolve Air Leaks After Lung Surgery Based on Nonparametric Modeling. Bayesian Anal. 2017, 12, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thall, P.F. Bayesian Utility-Based Designs for Subgroup-Specific Treatment Comparison and Early-Phase Dose Optimization in Oncology Clinical Trials. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Rademacher, J.G.; Hillman, S.; Storrick, E.; Mahoney, M.R.; Thall, P.F.; Jatoi, A.; Mandrekar, S.J. Adverse Event Burden Score-A Versatile Summary Measure for Cancer Clinical Trials. Cancers 2020, 12, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, P.; Lloyd, A.; Nathan, P.; Choueiri, T.K.; Cella, D.; Neary, M.P. Elicitation of health state utilities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Med. Res. Opin 2010, 26, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R. Cost-utility analysis. BMJ 1993, 307, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kind, P.; Lafata, J.E.; Matuszewski, K.; Raisch, D. The use of QALYs in clinical and patient decision-making: Issues and prospects. Value Health 2009, 12 (Suppl. 1), S27–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. An introduction to patient decision aids. BMJ 2013, 347, f4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Legare, F.; Lewis, K.B. Patient Decision Aids to Engage Adults in Treatment or Screening Decisions. JAMA 2017, 318, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, D.; Legare, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Task | Scale Used | Example Outputs | Distinct Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical estimation | Estimation scale | Hazard ratios (derived from loge hazards) Odds ratios (derived from loge odds) | Simple, powerful, and flexible summaries of effect size differences; not directly interpretable clinically but can be used to compare clinical effects of interest; non-collapsible parameters may be preferable for categorical and time-to-event models |

| Clinical outcome prediction | Outcome scale | Median survival, mean survival, three-month survival probability, one-year survival probability, risk difference, absolute risk reduction | Interpretable by clinicians and patients; require knowledge of each patient’s baseline prognostic risk for the outcome of interest; can directly contradict each other depending on which parametric effect is used; collapsible parameters are preferable for categorical and time-to-event outcomes |

| Clinical decision making | Utility scale | Utility of clinical outcomes | Allows a focus on the clinical outcomes of interest for specific patient prognostic groups; depends on the subjective goals and values of the patient/decision-maker |

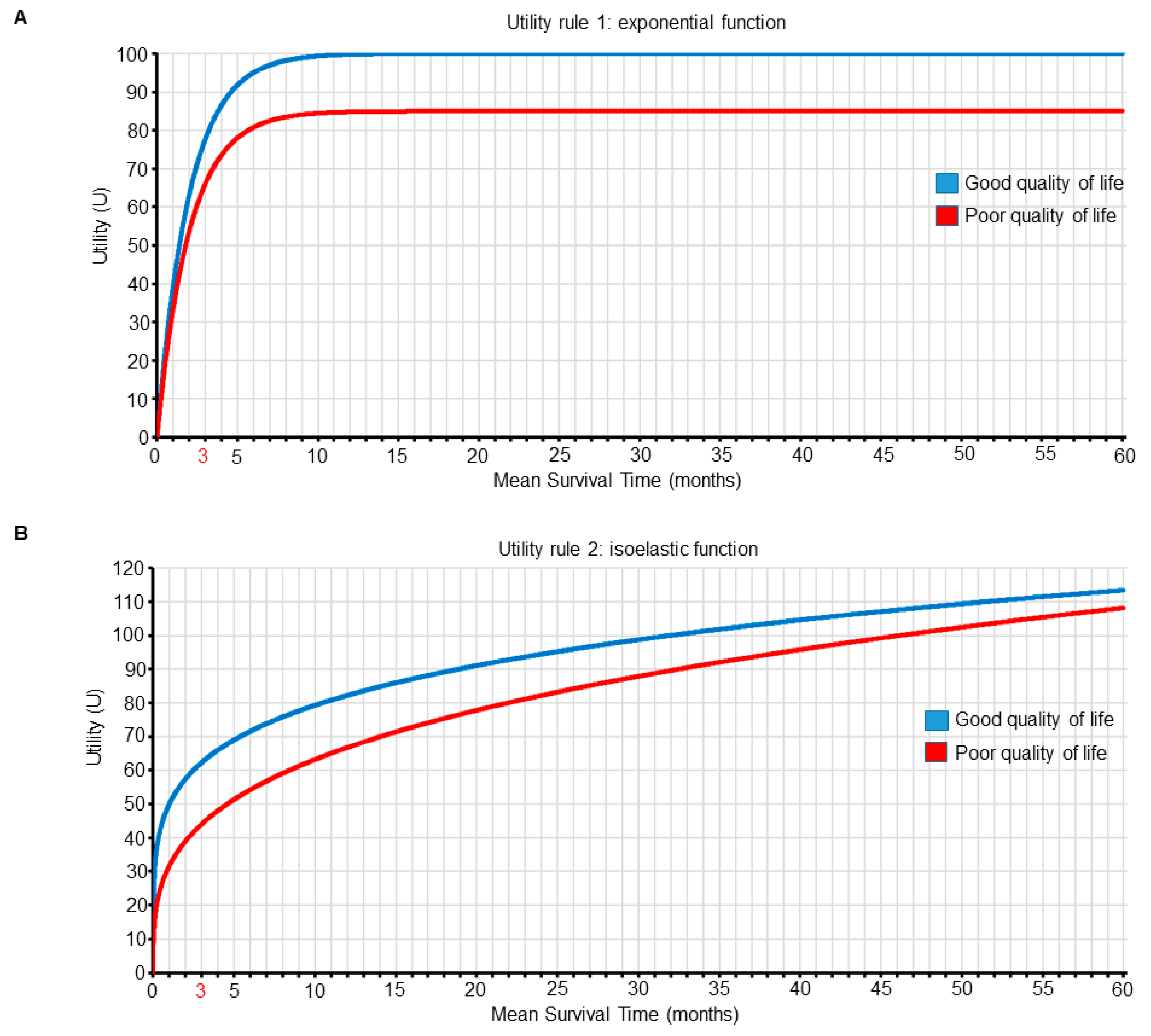

| Mean Survival Time (Months) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 |

| Good | 39 | 63 | 78 | 86 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Poor | 33 | 53 | 66 | 74 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 |

| Mean Survival Time (Months) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 |

| Good | 50 | 57 | 62 | 66 | 82 | 89 | 94 | 99 | 103 |

| Poor | 32 | 39 | 44 | 48 | 67 | 75 | 82 | 88 | 93 |

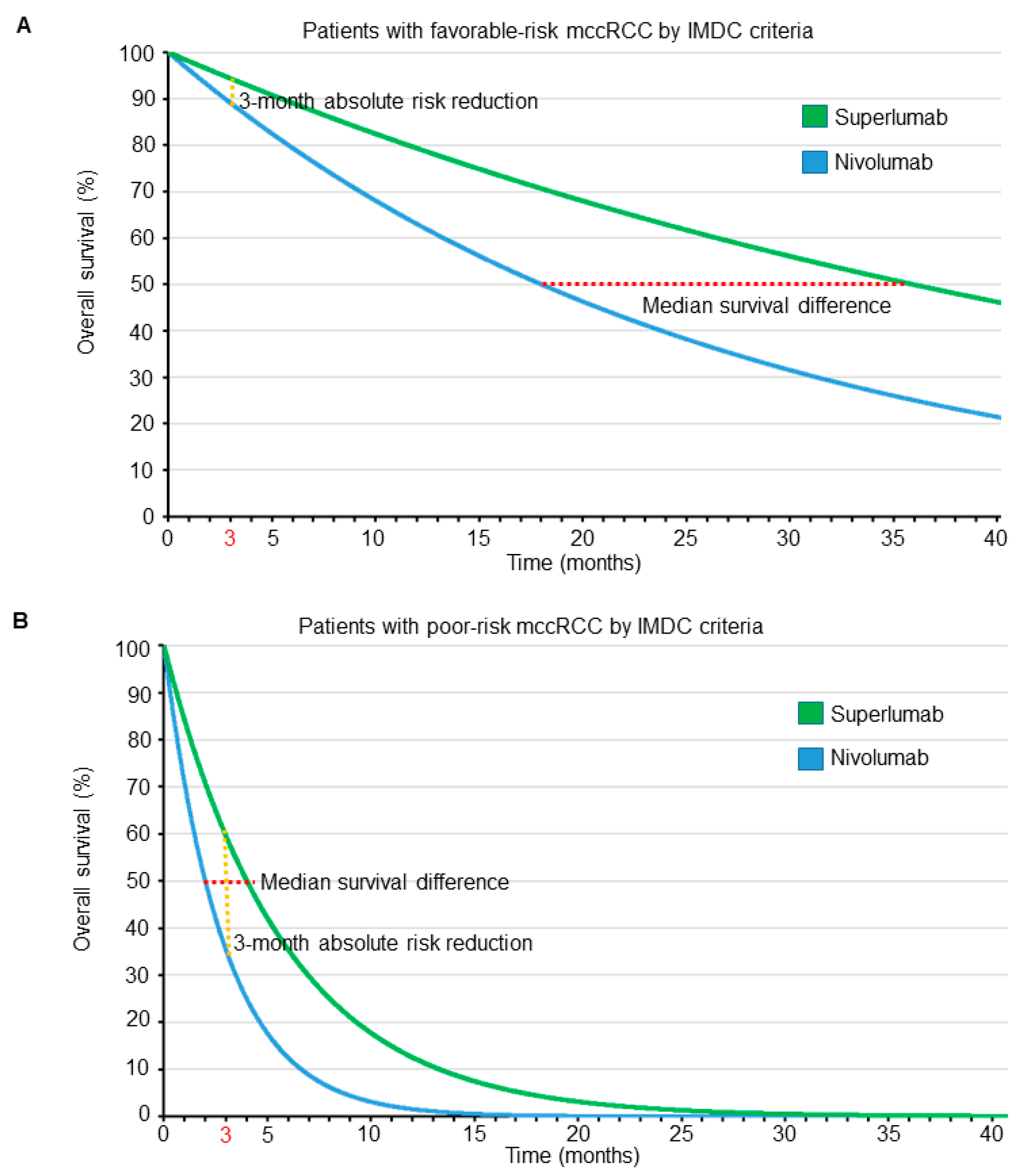

| Parameter | Patient A | Patient B | Conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMDC prognostic subgroup | Favorable risk | Poor risk | The two patients differ only in their prognostic status | ||

| Nivolumab | Superlumab | Nivolumab | Superlumab | ||

| Median overall survival (months) | 18 | 36 | 2 | 4 | The median and mean survival differences are more pronounced for patient A compared with patient B |

| Mean overall survival (months) | 26 | 52 | 5.8 | 2.9 | |

| Survival probablity at 3 months | 89% | 94% | 35% | 60% | The absolute risk reduction at 3 months is more pronounced for patient B compared with patient A |

| Utilities based on the first joint utility function (Figure 5A and Table 2) | 100 | 85 | 76 | 80 | Choose nivolumab for patient A and superlumab for patient B |

| Utilities based on the second joint utility function (Figure 5B and Table 3) | 96 | 109 | 62 | 56 | Choose superlumab for patient A and nivolumab for patient B |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Msaouel, P.; Lee, J.; Thall, P.F. Making Patient-Specific Treatment Decisions Using Prognostic Variables and Utilities of Clinical Outcomes. Cancers 2021, 13, 2741. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112741

Msaouel P, Lee J, Thall PF. Making Patient-Specific Treatment Decisions Using Prognostic Variables and Utilities of Clinical Outcomes. Cancers. 2021; 13(11):2741. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112741

Chicago/Turabian StyleMsaouel, Pavlos, Juhee Lee, and Peter F. Thall. 2021. "Making Patient-Specific Treatment Decisions Using Prognostic Variables and Utilities of Clinical Outcomes" Cancers 13, no. 11: 2741. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112741

APA StyleMsaouel, P., Lee, J., & Thall, P. F. (2021). Making Patient-Specific Treatment Decisions Using Prognostic Variables and Utilities of Clinical Outcomes. Cancers, 13(11), 2741. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112741