Assessing the Current State of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention: A Comprehensive Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

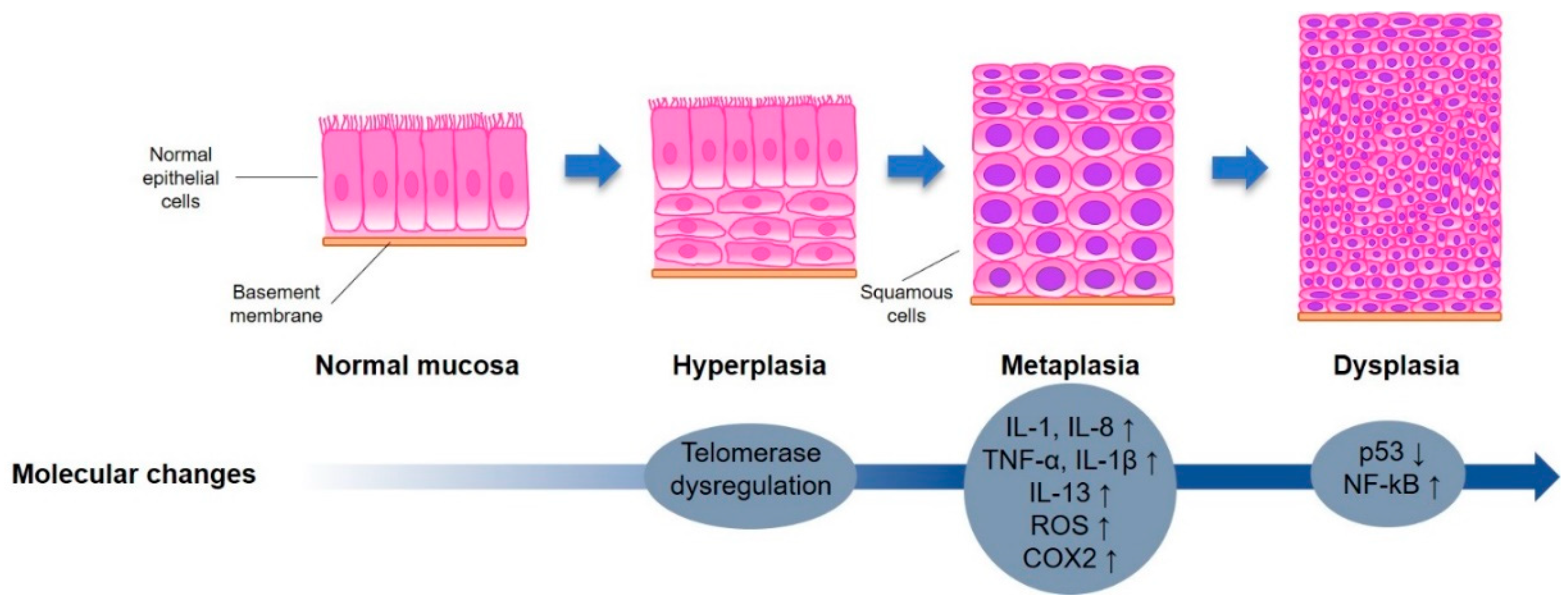

2. Lung Carcinogenesis

2.1. Role of Nicotine in the Onset of Lung Cancer

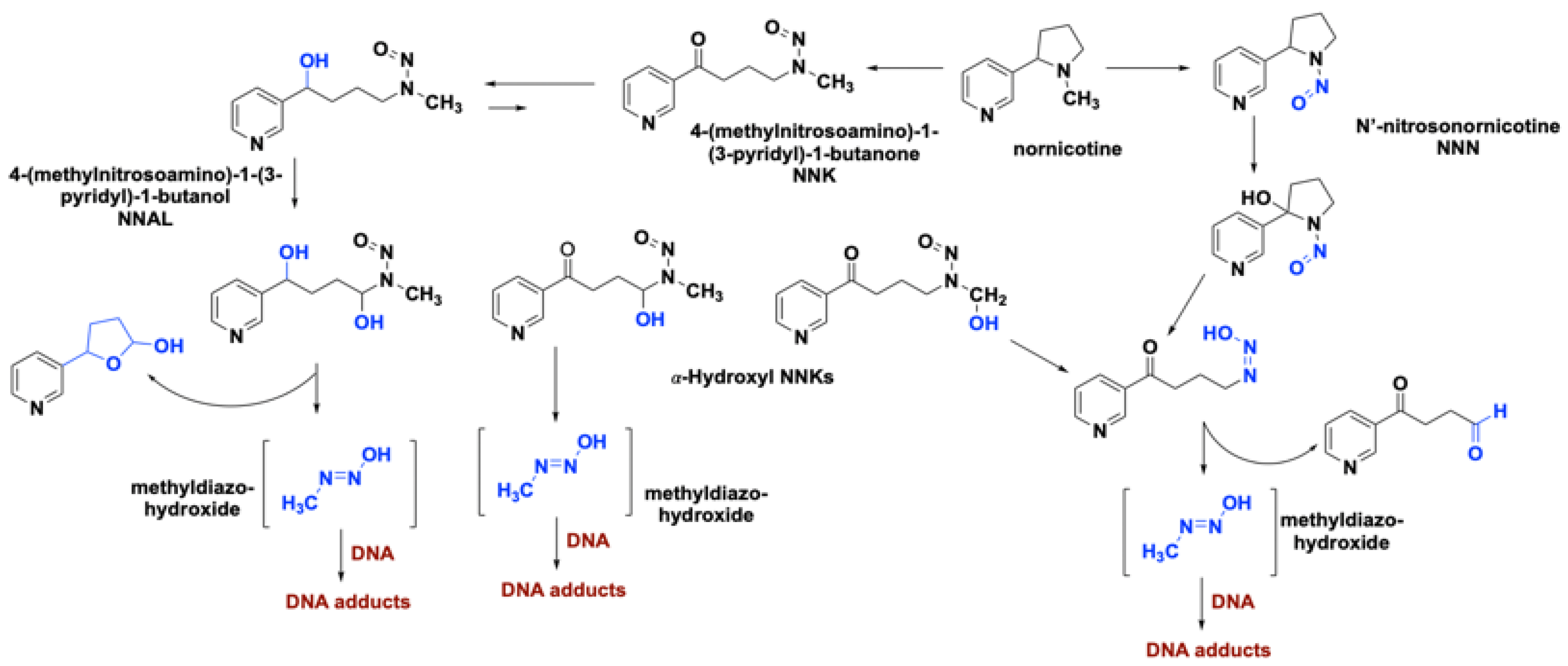

2.2. Role of Smoking-Associated Toxins in the Initiation of Lung Cancer

2.3. Bio-Molecular Pathways Involved in Lung Carcinogenesis

2.3.1. Inflammation

2.3.2. Oxidative Stress

2.3.3. Proliferative/Growth Signaling

2.3.4. Downregulation of Protective Mechanism

3. Chemoprevention Strategies for Lung Cancer

3.1. Modulation of Tumorigenic Pathways as a Chemoprevention Strategy in Lung Cancer

3.2. Drug Repurposing in the Area of Lung Chemoprevention

3.2.1. Anti-Inflammatory Compounds as Chemopreventive Agents

3.2.2. Modulators of Signaling Pathways

4. Examples of New Chemopreventive Strategies

4.1. Alteration of Paracrine Signaling of Endothelial Cells as a Tertiary Cancer Prevention Strategy

4.2. Synthetic Lethality Strategy

4.3. Modulation of Lung Microbiome

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4-ABP | 4-aminobiphenyl |

| 8-oxoG | 8-oxi-7,8-dihydroguanine |

| AAH | Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting-enzyme |

| Ach | acetylcholine |

| ADC | Adenocarcinoma |

| ALK | Anaplastic lymphoma kinase |

| ARBs | Angiotensin receptor blockers |

| ARE | Antioxidant response element |

| ATBC | Alpha-Tocopherol Beta Carotene |

| B(a)P | Benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) |

| CARET | β-Carotene and Retinol efficacy Study |

| CDC | Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CIS | Squamous dysplasia and carcinoma |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| DEC | Dysfunctional endothelial cells |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EVALI | E-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury |

| HNE | Trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| IEN | Intraepithelial neoplasia |

| Keap-1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| nAChR | nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| NNAL | Nnitrosamine alcohol |

| NNK | Nitrosamine ketone |

| NNN | N-nitrosonicotine |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| p38 MAPK | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| PGE-2 | COX2/prostaglandin E2 |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinomas |

| Se | Selenium |

| TKIs | TK inhibitors |

| TZD | Thiazolidinedione |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General; US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004.

- Links, C. Surgeon General’s Advisory on E-Cigarette Use among Youth; Arizona Free Press: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Gentzke, A.S.; Apelberg, B.J.; Jamal, A.; King, B.A. Use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United states, 2011–2018. Mmwr-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1276–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiani, D.C. Vaping-induced acute lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 960–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuramochi, J.; Inase, N.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kawachi, H.; Takemura, T.; Yoshizawa, Y. Lung cancer in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Respiration 2011, 82, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, D.M.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Pisani, P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005, 55, 74–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Schiller, J.H.; Gazdar, A.F. Lung cancer in never smokers—A different disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolle, E.; Pichler, M. Non-smoking-associated lung cancer: A distinct entity in terms of tumor biology, patient characteristics and impact of hereditary cancer predisposition. Cancers 2019, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Takada, M.; Kubo, A.; Matsumura, A.; Fukai, S.; Tamura, A.; Saito, R.; Kawahara, M.; Maruyama, Y. Gender, histology, and time of diagnosis are important factors for prognosis: Analysis of 1499 never-smokers with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in japan. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, I.; Ishikawa, S.; Ando, W.; Sohara, Y. Lung adenocarcinoma in never smokers: Problems of primary prevention from aspects of susceptible genes and carcinogens. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 6207–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, E.; Gazdar, A. Pathogenesis of lung cancer signalling pathways: Roadmap for therapies. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 1485–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloff, G.J.; Lippman, S.M.; Dannenberg, A.J.; Sigman, C.C.; Pearce, H.L.; Reid, B.J.; Szabo, E.; Jordan, V.C.; Spitz, M.R.; Mills, G.B.; et al. Progress in chemoprevention drug development: The promise of molecular biomarkers for prevention of intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer—A plan to move forward. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 3661–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, A.S.; Kim, E.S.; Hong, W.K. Chemoprevention of cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004, 54, 150–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapproth, H.; Reinheimer, T.; Metzen, J.; Munch, M.; Bittinger, F.; Kirkpatrick, C.J.; Hohle, K.D.; Schemann, M.; Racke, K.; Wessler, I. Non-neuronal acetylcholine, a signalling molecule synthezised by surface cells of rat and man. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1997, 355, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grando, S.A. Connections of nicotine to cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykhmus, O.; Gergalova, G.; Koval, L.; Zhmak, M.; Komisarenko, S.; Skok, M. Mitochondria express several nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes to control various pathways of apoptosis induction. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 53, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grando, S.A.; Pittelkow, M.R.; Schallreuter, K.U. Adrenergic and cholinergic control in the biology of epidermis: Physiological and clinical significance. J. Investig. Derm. 2006, 126, 1948–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyavsky, A.I.; Shchepotin, I.B.; Galitovkiy, V.; Grando, S.A. Mechanisms of tumor-promoting activities of nicotine in lung cancer: Synergistic effects of cell membrane and mitochondrial nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergalova, G.L.; Likhmous, O.Y.; Skok, M.V. Possible influence of a7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation in the mitochondrial membrane on apoptosis development. Neurophysiology 2011, 43, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. Impact of tobacco smoke in hiv progression: A major risk factor for the development of neuroaids and associated cns disorders. J. Public Health 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S.S. Lung carcinogenesis by tobacco smoke. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 2724–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S.S. Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific n-nitrosamines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998, 11, 559–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, S.S.; Hoffmann, D. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines, an important group of carcinogens in tobacco and tobacco smoke. Carcinogenesis 1988, 9, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistuba, I.I.; Lam, S.; Behrens, C.; Virmani, A.K.; Fong, K.M.; LeRiche, J.; Samet, J.M.; Srivastava, S.; Minna, J.D.; Gazdar, A.F. Molecular damage in the bronchial epithelium of current and former smokers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997, 89, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, A.; Sivandzade, F.; Archie, S.R.; Cucullo, L. Public health policies on e-cigarettes. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2019, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, K.J.; Dalgleish, A.G. Chronic immune activation and inflammation as the cause of malignancy. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Perfetti, T.A.; King, J.A. Perspectives on pulmonary inflammation and lung cancer risk in cigarette smokers. Inhal. Toxicol. 2006, 18, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysich, K.B.; Menezes, R.J.; Ronsani, A.; Swede, H.; Reid, M.E.; Cummings, K.M.; Falkner, K.L.; Loewen, G.M.; Bepler, G. Regular aspirin use and lung cancer risk. BMC Cancer 2002, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, K.R.; D’hulst, A.I.; Maes, T.; Moerloose, K.B.; Demedts, I.K.; Lebecque, S.; Joos, G.F.; Brusselle, G.G. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation and emphysema are attenuated in ccr6-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 4350–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, D.K.; Hirata, F.; Rishi, A.K.; Gairola, C.G. Cigarette smoke, inflammation, and lung injury: A mechanistic perspective. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B Crit. Rev. 2009, 12, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudkov, A.V.; Komarova, E.A. P53 and the carcinogenicity of chronic inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, I.; Tanaka, N. Role of p53 in the regulation of the inflammatory tumor microenvironment and tumor suppression. Cancers 2018, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwano, K.; Kunitake, R.; Kawasaki, M.; Nomoto, Y.; Hagimoto, N.; Nakanishi, Y.; Hara, N. P21waf1/cip1/sdi1 and p53 expression in association with DNA strand breaks in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 154, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filaire, E.; Dupuis, C.; Galvaing, G.; Aubreton, S.; Laurent, H.; Richard, R.; Filaire, M. Lung cancer: What are the links with oxidative stress, physical activity and nutrition. Lung Cancer 2013, 82, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kino, K.; Sugiyama, H. Possible cause of g-c-->c-g transversion mutation by guanine oxidation product, imidazolone. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Elizur, T.; Sevilya, Z.; Leitner-Dagan, Y.; Elinger, D.; Roisman, L.C.; Livneh, Z. DNA repair of oxidative DNA damage in human carcinogenesis: Potential application for cancer risk assessment and prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008, 266, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Elizur, T.; Elinger, D.; Leitner-Dagan, Y.; Blumenstein, S.; Krupsky, M.; Berrebi, A.; Schechtman, E.; Livneh, Z. Development of an enzymatic DNA repair assay for molecular epidemiology studies: Distribution of ogg activity in healthy individuals. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Elizur, T.; Krupsky, M.; Blumenstein, S.; Elinger, D.; Schechtman, E.; Livneh, Z. DNA repair activity for oxidative damage and risk of lung cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Elizur, T.; Elinger, D.; Blumenstein, S.; Krupsky, M.; Schechtman, E.; Livneh, Z. Novel molecular targets for risk identification: DNA repair enzyme activities. Cancer Biomark. 2007, 3, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, H.; Nair, J. Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation-derived DNA-lesions in inflammation driven carcinogenesis. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2004, 28, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, H.; McGavin, M.; Orloff, M.; Riechert, A.; Porter, B. Simultaneous exposure to nicotine and hyperoxia causes tumors in hamsters. Lab. Investig. A J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 1995, 73, 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Schaal, C.; Chellappan, S.P. Nicotine-mediated cell proliferation and tumor progression in smoking-related cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, H.M.; Jull, B.A.; Sheppard, B.J.; Plummer, H.K. Interaction of tobacco-specific toxicants with the neuronal alpha(7) nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and its associated mitogenic signal transduction pathway: Potential role in lung carcinogenesis and pediatric lung disorders. Eur. J. Pharm. 2000, 393, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, D.L.; Liu, X.; Hopkins, T.M.; Swick, M.C.; Dhir, R.; Siegfried, J.M. Nicotine activates cell-signaling pathways through muscle-type and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Pulm Pharm. 2007, 20, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Pillai, S.; Chellappan, S. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling in tumor growth and metastasis. J. Oncol. 2011, 2011, 456743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurutani, J.; Castillo, S.S.; Brognard, J.; Granville, C.A.; Zhang, C.; Gills, J.J.; Sayyah, J.; Dennis, P.A. Tobacco components stimulate akt-dependent proliferation and nfκb-dependent survival in lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, F.R.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Bunn, P.A., Jr.; Di Maria, M.V.; Veve, R.; Bremmes, R.M.; Baron, A.E.; Zeng, C.; Franklin, W.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: Correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3798–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdar, A.F.; Minna, J.D. Deregulated egfr signaling during lung cancer progression: Mutations, amplicons, and autocrine loops. Cancer Prev. Res. 2008, 1, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdar, A.F.; Shigematsu, H.; Herz, J.; Minna, J.D. Mutations and addiction to egfr: The achilles ‘heal’ of lung cancers? Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigematsu, H.; Gazdar, A.F. Somatic mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway in lung cancers. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, J.A.; Cantley, L.C. The role of the erbb family members in non-small cell lung cancers sensitive to epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 4372s–4376s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, W.; Wang, T.Y.; Riely, G.J.; Miller, V.A.; Pan, Q.; Ladanyi, M.; Zakowski, M.F.; Heelan, R.T.; Kris, M.G.; Varmus, H.E. Kras mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riely, G.J.; Politi, K.A.; Miller, V.A.; Pao, W. Update on epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7232–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soda, M.; Choi, Y.L.; Enomoto, M.; Takada, S.; Yamashita, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Fujiwara, S.; Watanabe, H.; Kurashina, K.; Hatanaka, H.; et al. Identification of the transforming eml4-alk fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 2007, 448, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Molecular mechanisms of the keap1–nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells 2011, 16, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Sato, H.; Nishimura, N.; Takahashi, S.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M. Accelerated DNA adduct formation in the lung of the nrf2 knockout mouse exposed to diesel exhaust. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2001, 173, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, T.; Ishii, Y.; Itoh, K.; Kiwamoto, T.; Kimura, T.; Matsuno, Y.; Morishima, Y.; Hegab, A.E.; Homma, S.; Nomura, A.; et al. Nrf2-deficient mice are highly susceptible to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Genes Cells 2005, 10, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Villeneuve, N.F.; Sun, Z.; Wong, P.K.; Zhang, D.D. Dual roles of nrf2 in cancer. Pharm. Res. 2008, 58, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A.; Johnson, D.A.; Kraft, A.D.; Calkins, M.J.; Jakel, R.J.; Vargas, M.R.; Chen, P.-C. The nrf2-are pathway: An indicator and modulator of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Hannink, M. Distinct cysteine residues in keap1 are required for keap1-dependent ubiquitination of nrf2 and for stabilization of nrf2 by chemopreventive agents and oxidative stress. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 8137–8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levonen, A.L.; Landar, A.; Ramachandran, A.; Ceaser, E.K.; Dickinson, D.A.; Zanoni, G.; Morrow, J.D.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Cellular mechanisms of redox cell signalling: Role of cysteine modification in controlling antioxidant defences in response to electrophilic lipid oxidation products. Biochem. J. 2004, 378, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Wakabayashi, J.; Maher, J.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of keap1 in determining nrf2 activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 2758–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera-Rodriguez, R. Importance of the keap1-nrf2 pathway in nsclc: Is it a possible biomarker? Biomed. Rep. 2018, 9, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rachakonda, G.; Sekhar, K.R.; Jowhar, D.; Samson, P.C.; Wikswo, J.P.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Datta, P.K.; Freeman, M.L. Increased cell migration and plasticity in nrf2-deficient cancer cell lines. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3703–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, M.H.; Lee, W.J.; Hsieh, F.K.; Li, C.F.; Cheng, T.Y.; Wang, M.Y.; Chen, J.S.; Chow, J.M.; Jan, Y.H.; Hsiao, M.; et al. Keap1-nrf2 interaction suppresses cell motility in lung adenocarcinomas by targeting the s100p protein. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4719–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerins, M.J.; Ooi, A. The roles of nrf2 in modulating cellular iron homeostasis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1756–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lippman, S.M. An intermittent approach for cancer chemoprevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, P.; Kelloff, G.; Burch-Whitman, C.; Kramer, B.S. Chemoprevention. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1995, 45, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopala, S.V.; Vashee, S.; Oldfield, L.M.; Suzuki, Y.; Venter, J.C.; Telenti, A.; Nelson, K.E. The human microbiome and cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2017, 10, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivarelli, S.; Salemi, R.; Candido, S.; Falzone, L.; Santagati, M.; Stefani, S.; Torino, F.; Banna, G.L.; Tonini, G.; Libra, M. Gut microbiota and cancer: From pathogenesis to therapy. Cancers 2019, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, R.J.; Pazienza, V. Impact of different types of diet on gut microbiota profiles and cancer prevention and treatment. Medicina 2019, 55, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachida, S.; Mizutani, S.; Shiroma, H.; Shiba, S.; Nakajima, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Watanabe, H.; Masuda, K.; Nishimoto, Y.; Kubo, M.; et al. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal distinct stage-specific phenotypes of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zackular, J.P.; Rogers, M.A.; Ruffin, M.T.t.; Schloss, P.D. The human gut microbiome as a screening tool for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2014, 7, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Ren, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. Lung-cancer chemoprevention by induction of synthetic lethality in mutant kras premalignant cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidle, U.H.; Maisel, D.; Eick, D. Synthetic lethality-based targets for discovery of new cancer therapeutics. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2011, 8, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, R.L. Chemoprevention of lung cancer. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2009, 6, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Rao, S.K.; Popper, H.H.; Cagle, P.T.; Fraire, A.E. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung: A probable forerunner in the development of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Mod. Pathol. 2001, 14, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, W.H. Early glandular neoplasia of the lung. Respir. Res. 2000, 1, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licchesi, J.D.; Westra, W.H.; Hooker, C.M.; Herman, J.G. Promoter hypermethylation of hallmark cancer genes in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2570–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.T.; Roth, M.D.; Fishbein, M.C.; Aberle, D.R.; Zhang, Z.F.; Rao, J.Y.; Tashkin, D.P.; Goodglick, L.; Holmes, E.C.; Cameron, R.B.; et al. Lung cancer chemoprevention with celecoxib in former smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, M.; Kohno, H.; Kakizawa, K.; Iizasa, T.; Otsuji, M.; Saitoh, Y.; Hiroshima, K.; Ohwada, H.; Fujisawa, T. Ki-67 immunostaining and other prognostic factors including tobacco smoking in patients with resected nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 89, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolmark, N.; Dunn, B.K. The role of tamoxifen in breast cancer prevention: Issues sparked by the nsabp breast cancer prevention trial (p-1). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 949, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, C.V.; Reddy, B.S. Nsaids and chemoprevention. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2004, 4, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Rabadi, L.; Bergan, R. A way forward for cancer chemoprevention: Think local. Cancer Prev. Res. 2017, 10, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ambrosio, C.; Ferber, A.; Resnicoff, M.; Baserga, R. A soluble insulin-like growth factor i receptor that induces apoptosis of tumor cells in vivo and inhibits tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 4013–4020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Majumder, P.K.; Febbo, P.G.; Bikoff, R.; Berger, R.; Xue, Q.; McMahon, L.M.; Manola, J.; Brugarolas, J.; McDonnell, T.J.; Golub, T.R.; et al. Mtor inhibition reverses akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and hif-1-dependent pathways. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blot, W.J.; Li, J.Y.; Taylor, P.R.; Guo, W.; Dawsey, S.; Wang, G.Q.; Yang, C.S.; Zheng, S.F.; Gail, M.; Li, G.Y.; et al. Nutrition intervention trials in linxian, china: Supplementation with specific vitamin/mineral combinations, cancer incidence, and disease-specific mortality in the general population. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.M.; Ross, S.A. Beta-carotene increases lung cancer incidence in cigarette smokers. Nutr. Rev. 1996, 54, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpha-Tocopherol, B.C.C.P.S.G. The effect of vitamin e and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Virtamo, J.; Pietinen, P.; Huttunen, J.K.; Korhonen, P.; Malila, N.; Virtanen, M.J.; Albanes, D.; Taylor, P.R.; Albert, P.; Group, A.S. Incidence of cancer and mortality following alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene supplementation: A postintervention follow-up. JAMA 2003, 290, 476–485. [Google Scholar]

- Omenn, G.S.; Goodman, G.E.; Thornquist, M.D.; Balmes, J.; Cullen, M.R.; Glass, A.; Keogh, J.P.; Meyskens, F.L.; Valanis, B.; Williams, J.H.; et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin a on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresso, K.C.; Tsai, K.Y.; Brown, P.H.; Szabo, E.; Lippman, S.; Hawk, E.T. Molecular cancer prevention: Current status and future directions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 345–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennekens, C.H.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.; Rosner, B.; Cook, N.R.; Belanger, C.; LaMotte, F.; Gaziano, J.M.; Ridker, P.M.; et al. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with beta carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redlich, C.A.; Blaner, W.S.; Van Bennekum, A.M.; Chung, J.S.; Clever, S.L.; Holm, C.T.; Cullen, M.R. Effect of supplementation with beta-carotene and vitamin a on lung nutrient levels. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1998, 7, 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, L.H.; Burton, G.; Kelly, F.J. Plasma rrr-alpha-tocopherol concentrations are lower in smokers than in non-smokers after ingestion of a similar oral load of this antioxidant vitamin. Clin. Sci. 1997, 92, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyskens, F.L., Jr.; Szabo, E. Diet and cancer: The disconnect between epidemiology and randomized clinical trials. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 1366–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhuo, H.; Smith, A.H.; Steinmaus, C. Selenium and lung cancer: A quantitative analysis of heterogeneity in the current epidemiological literature. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 771–778. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, H.; Kennedy, D.; Fergusson, D.; Fernandes, R.; Cooley, K.; Seely, A.; Sagar, S.; Wong, R.; Seely, D. Selenium and lung cancer: A systematic review and meta analysis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.E.; Duffield-Lillico, A.J.; Garland, L.; Turnbull, B.W.; Clark, L.C.; Marshall, J.R. Selenium supplementation and lung cancer incidence: An update of the nutritional prevention of cancer trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2002, 11, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, D.D.; Lee, S.J.; Keller, S.M.; Wright, G.S.; Aisner, S.; Belinsky, S.A.; Johnson, D.H.; Johnston, M.R.; Goodman, G.; Clamon, G.; et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase iii chemoprevention trial of selenium supplementation in patients with resected stage i non-small-cell lung cancer: Ecog 5597. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4179–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, H.; Azim, S.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, M.A.; Patel, G.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P. Cancer chemoprevention by phytochemicals: Nature’s healing touch. Molecules 2017, 22, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, J.M.; Chiang, T.A.; Chang, W.T.; Chao, C.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, G.Y.; Shih, Y.X.; Shih, Y.W. Plumbagin inhibits tpa-induced mmp-2 and u-pa expressions by reducing binding activities of nf-kappab and ap-1 via erk signaling pathway in a549 human lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2010, 335, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, Y.C.; Ho, C.T.; Pan, M.H. Recent advances in cancer chemoprevention with phytochemicals. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Khor, T.O.; Shu, L.; Su, Z.Y.; Fuentes, F.; Lee, J.H.; Kong, A.N. Plants vs. Cancer: A review on natural phytochemicals in preventing and treating cancers and their druggability. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 1281–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Bi, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gong, Y.; Shi, J.; Xu, L. Cancer chemoprevention and therapy using chinese herbal medicine. Biol. Proced. Online 2018, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotecha, R.; Takami, A.; Espinoza, J.L. Dietary phytochemicals and cancer chemoprevention: A review of the clinical evidence. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 52517–52529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.H.; Barve, A.; Yu, S.; Huang, M.T.; Kong, A.N. Cancer chemoprevention by phytochemicals: Potential molecular targets, biomarkers and animal models. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2007, 28, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Carmella, S.G.; Hochalter, J.B.; Rauch, D.; Oliver, A.; Jensen, J.; Hatsukami, D.K.; Upadhyaya, P.; Hecht, S.S.; et al. Phenanthrene metabolism in smokers: Use of a two-step diagnostic plot approach to identify subjects with extensive metabolic activation. J. Pharm. Exp. 2012, 342, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, S.M.; Royce, S.G.; Licciardi, P.V.; Karagiannis, T.C. Dietary sulforaphane in cancer chemoprevention: The role of epigenetic regulation and hdac inhibition. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 22, 1382–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Monisha, J.; Roy, N.K.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical: Multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. Br. J. Pharm. 2017, 174, 1325–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, A.; Wahid, F.; Lee, Y.S. Curcumin in cancer chemoprevention: Molecular targets, pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and clinical trials. Arch. Pharm. 2010, 343, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pricci, M.; Girardi, B.; Giorgio, F.; Losurdo, G.; Ierardi, E.; Di Leo, A. Curcumin and colorectal cancer: From basic to clinical evidences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Harsha, C.; Banik, K.; Vikkurthi, R.; Sailo, B.L.; Bordoloi, D.; Gupta, S.C.; Aggarwal, B.B. Is curcumin bioavailability a problem in humans: Lessons from clinical trials. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dance-Barnes, S.T.; Kock, N.D.; Moore, J.E.; Lin, E.Y.; Mosley, L.J.; D’Agostino, R.B., Jr.; McCoy, T.P.; Townsend, A.J.; Miller, M.S. Lung tumor promotion by curcumin. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lian, F.; Smith, D.E.; Russell, R.M.; Wang, X.D. Lycopene supplementation inhibits lung squamous metaplasia and induces apoptosis via up-regulating insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 in cigarette smoke-exposed ferrets. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3138–3144. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, J.L.; An, D.T.; Trung, L.Q.; Yamada, K.; Nakao, S.; Takami, A. Stilbene derivatives from melinjo extract have antioxidant and immune modulatory effects in healthy individuals. Integr. Mol. Med. 2015, 2, 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.D.; Lu, H.X.; Xu, L.S.; Xiao, W. Polyphyllin d exerts potent anti-tumour effects on lewis cancer cells under hypoxic conditions. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009, 37, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Dai, L.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J. Ganoderic acid dm induces autophagic apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by inhibiting the pi3k/akt/mtor activity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 316, 108932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, J.X.; Yang, C.S.; Yang, M.Q.; Deng, Y.; Wang, H. Gene regulation mediated by micrornas in response to green tea polyphenol egcg in mouse lung cancer. BMC Genom. 2014, 15 (Suppl. 11), S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xu, C.; Zheng, L.; Wang, K.; Jin, M.; Sun, Y.; Yue, Z. Polyphyllin vii induces apoptotic cell death via inhibition of the pi3k/akt and nfkappab pathways in a549 human lung cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, I.; Sharma, M.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Combinatorial epigenetics impact of polyphenols and phytochemicals in cancer prevention and therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, A.; Wang, X.; Shan, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Jiang, P.; Feng, Q. Curcumin reactivates silenced tumor suppressor gene rarbeta by reducing DNA methylation. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Bi, L.; Luo, H.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Wei, G.; Chen, W. Water extract of ginseng and astragalus regulates macrophage polarization and synergistically enhances ddp’s anticancer effect. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 232, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granchi, C.; Fortunato, S.; Meini, S.; Rizzolio, F.; Caligiuri, I.; Tuccinardi, T.; Lee, H.Y.; Hergenrother, P.J.; Minutolo, F. Characterization of the saffron derivative crocetin as an inhibitor of human lactate dehydrogenase 5 in the antiglycolytic approach against cancer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 5639–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walser, T.; Cui, X.; Yanagawa, J.; Lee, J.M.; Heinrich, E.; Lee, G.; Sharma, S.; Dubinett, S.M. Smoking and lung cancer: The role of inflammation. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.E.; Beebe-Donk, J.; Schuller, H.M. Chemoprevention of lung cancer by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among cigarette smokers. Oncol. Rep. 2002, 9, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasky, T.M.; Baik, C.S.; Slatore, C.G.; Alvarado, M.; White, E. Prediagnostic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and lung cancer survival in the vital study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2012, 7, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Hong, W.K.; Lee, J.J.; Mao, L.; Morice, R.C.; Liu, D.D.; Jimenez, C.A.; Eapen, G.A.; Lotan, R.; Tang, X.; et al. Biological activity of celecoxib in the bronchial epithelium of current and former smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, A.B.; Dubinett, S.M. Cox-2 inhibition and lung cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2004, 31, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R.; Lee, I.M.; Zhang, S.M.; Moorthy, M.V.; Buring, J.E. Alternate-day, low-dose aspirin and cancer risk: Long-term observational follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishodia, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Cyclooxygenase (cox)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates activation of cigarette smoke-induced nuclear factor (nf)-kappab by suppressing activation of ikappabalpha kinase in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: Correlation with suppression of cyclin d1, cox-2, and matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5004–5012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.T.; Fishbein, M.C.; Adams, B.; Roth, M.D.; Goodglick, L.; Hong, L.; Burdick, M.; Strieter, E.R.; Holmes, C.; Tashkin, D.P.; et al. Celecoxib decreases ki-67 proliferative index in active smokers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemenoff, R.; Meyer, A.M.; Hudish, T.M.; Mozer, A.B.; Snee, A.; Narumiya, S.; Stearman, R.S.; Winn, R.A.; Weiser-Evans, M.; Geraci, M.W.; et al. Prostacyclin prevents murine lung cancer independent of the membrane receptor by activation of peroxisomal proliferator--activated receptor gamma. Cancer Prev. Res. 2008, 1, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R.L.; Blatchford, P.J.; Kittelson, J.; Minna, J.D.; Kelly, K.; Massion, P.P.; Franklin, W.A.; Mao, J.; Wilson, D.O.; Merrick, D.T.; et al. Oral iloprost improves endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Larsson, A.; Mattsson, H.; Hjertberg, E.; Dahlback, M.; Tunek, A.; Brattsand, R. Reversible fatty acid conjugation of budesonide. Novel mechanism for prolonged retention of topically applied steroid in airway tissue. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1998, 26, 623–630. [Google Scholar]

- Estensen, R.D.; Jordan, M.M.; Wiedmann, T.S.; Galbraith, A.R.; Steele, V.E.; Wattenberg, L.W. Effect of chemopreventive agents on separate stages of progression of benzo[alpha]pyrene induced lung tumors in a/j mice. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.; Li, Y.; Gunning, W.T.; Kramer, P.M.; Al-Yaqoub, F.; Lubet, R.A.; Steele, V.E.; Szabo, E.; Tao, L. Prevention of mouse lung tumors by budesonide and its modulation of biomarkers. Carcinogenesis 2002, 23, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattenberg, L.W.; Wiedmann, T.S.; Estensen, R.D.; Zimmerman, C.L.; Galbraith, A.R.; Steele, V.E.; Kelloff, G.J. Chemoprevention of pulmonary carcinogenesis by brief exposures to aerosolized budesonide or beclomethasone dipropionate and by the combination of aerosolized budesonide and dietary myo-inositol. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lam, S.; leRiche, J.C.; McWilliams, A.; Macaulay, C.; Dyachkova, Y.; Szabo, E.; Mayo, J.; Schellenberg, R.; Coldman, A.; Hawk, E.; et al. A randomized phase iib trial of pulmicort turbuhaler (budesonide) in people with dysplasia of the bronchial epithelium. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6502–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, G.; Szabo, E.; Decensi, A.; Guerrieri-Gonzaga, A.; Bellomi, M.; Radice, D.; Ferretti, S.; Pelosi, G.; Lazzeroni, M.; Serrano, D.; et al. Randomized phase ii trial of inhaled budesonide versus placebo in high-risk individuals with ct screen-detected lung nodules. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parimon, T.; Chien, J.W.; Bryson, C.L.; McDonell, M.B.; Udris, E.M.; Au, D.H. Inhaled corticosteroids and risk of lung cancer among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.F.; Kuo, H.C.; Lin, M.C.; Ho, S.C.; Tu, M.L.; Chen, Y.M.; Chen, Y.C.; Fang, W.F.; Wang, C.C.; Liu, G.H. Inhaled corticosteroids have a protective effect against lung cancer in female patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29711–29721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.H.; Szabo, E. Induction of differentiation and apoptosis by ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Ravi Kiran Ammu, V.V.V.; Garikapati, K.K.; Krishnamurthy, P.T.; Chintamaneni, P.K.; Pindiprolu, S. Possible role of ppar-gamma and cox-2 receptor modulators in the treatment of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 124, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, S.P.; Reddy, A.T.; Banno, A.; Reddy, R.C. Ppar agonists for the prevention and treatment of lung cancer. Ppar Res. 2017, 2017, 8252796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, R.; Ratnasinghe, L.; Simmons, D.L.; Siegel, E.R.; Midathada, M.V.; Kim, L.; Kim, P.J.; Owens, R.J.; Lang, N.P. Thiazolidinediones and the risk of lung, prostate, and colon cancer in patients with diabetes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; James, M.; Wen, W.; Lu, Y.; Szabo, E.; Lubet, R.A.; You, M. Chemopreventive effects of pioglitazone on chemically induced lung carcinogenesis in mice. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 3074–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Kong, A.W.; Yuan, H.; Ma, L.T.; Hsin, M.K.; Wan, I.Y.; Underwood, M.J.; Chen, G.G. Pioglitazone prevents smoking carcinogen-induced lung tumor development in mice. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2012, 12, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, P.J.; Rai, H.; Beukemann, M.; Xu, M.; Jain, A.; Sasidhar, M. The effect of metformin and thiazolidinedione use on lung cancer in diabetics. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.H. Pioglitazone and lung cancer risk in taiwanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2018, 44, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosetti, C.; Rosato, V.; Buniato, D.; Zambon, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Corrao, G. Cancer risk for patients using thiazolidinediones for type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Oncologist 2013, 18, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.L.; Blatchford, P.J.; Merrick, D.T.; Bunn, P.A., Jr.; Bagwell, B.; Dwyer-Nield, L.D.; Jackson, M.K.; Geraci, M.W.; Miller, Y.E. A randomized phase ii trial of pioglitazone for lung cancer chemoprevention in high-risk current and former smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2019, 12, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, S.A.; Li, G.; El-Kommos, A.; Kang, H.; Ramalingam, S.S.; Behera, M.; Gandhi, K.; Kowalski, J.; Sica, G.L.; Khuri, F.R.; et al. Class i hdacs are mediators of smoke carcinogen-induced stabilization of dnmt1 and serve as promising targets for chemoprevention of lung cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2014, 7, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, A.K.; Tsay, J.C.; Tchou-Wong, K.M.; Jorgensen, A.; Rom, W.N. Chemoprevention of lung cancer: Prospects and disappointments in human clinical trials. Cancers 2013, 5, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoPiccolo, J.; Blumenthal, G.M.; Bernstein, W.B.; Dennis, P.A. Targeting the pi3k/akt/mtor pathway: Effective combinations and clinical considerations. Drug Resist. Update 2008, 11, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott, R.M.; Dennis, P.A. The role of the akt/mtor pathway in tobacco carcinogen-induced lung tumorigenesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, A.S.; McDonnell, T.; Lam, S.; Putnam, J.B.; Bekele, N.; Hong, W.K.; Kurie, J.M. Increased phospho-akt (ser(473)) expression in bronchial dysplasia: Implications for lung cancer prevention studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2003, 12, 660–664. [Google Scholar]

- West, K.A.; Brognard, J.; Clark, A.S.; Linnoila, I.R.; Yang, X.; Swain, S.M.; Harris, C.; Belinsky, S.; Dennis, P.A. Rapid akt activation by nicotine and a tobacco carcinogen modulates the phenotype of normal human airway epithelial cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granville, C.A.; Warfel, N.; Tsurutani, J.; Hollander, M.C.; Robertson, M.; Fox, S.D.; Veenstra, T.D.; Issaq, H.J.; Linnoila, R.I.; Dennis, P.A. Identification of a highly effective rapamycin schedule that markedly reduces the size, multiplicity, and phenotypic progression of tobacco carcinogen-induced murine lung tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, P.A. Rapamycin for chemoprevention of upper aerodigestive tract cancers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2009, 2, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seabloom, D.E.; Galbraith, A.R.; Haynes, A.M.; Antonides, J.D.; Wuertz, B.R.; Miller, W.A.; Miller, K.A.; Steele, V.E.; Miller, M.S.; Clapper, M.L.; et al. Fixed-dose combinations of pioglitazone and metformin for lung cancer prevention. Cancer Prev. Res. 2017, 10, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J.M.; Donnelly, L.A.; Emslie-Smith, A.M.; Alessi, D.R.; Morris, A.D. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ 2005, 330, 1304–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decensi, A.; Puntoni, M.; Goodwin, P.; Cazzaniga, M.; Gennari, A.; Bonanni, B.; Gandini, S. Metformin and cancer risk in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, H.; Goto, A.; Tsujimoto, T.; Noda, M. Cancer risk in diabetic patients treated with metformin: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hense, H.W.; Geier, A.S. Re: “Reduced risk of lung cancer with metformin therapy in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 1130–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmedt, N.; Azoulay, L.; Hense, S. Re: “Reduced risk of lung cancer with metformin therapy in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 1216–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsai, M.J.; Yang, C.J.; Kung, Y.T.; Sheu, C.C.; Shen, Y.T.; Chang, P.Y.; Huang, M.S.; Chiu, H.C. Metformin decreases lung cancer risk in diabetic patients in a dose-dependent manner. Lung Cancer 2014, 86, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Bi, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, G.; Guo, Y.; Song, Q. Reduced risk of lung cancer with metformin therapy in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowall, B.; Stang, A.; Rathmann, W.; Kostev, K. No reduced risk of overall, colorectal, lung, breast, and prostate cancer with metformin therapy in diabetic patients: Database analyses from germany and the uk. Pharm. Drug Saf. 2015, 24, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Gills, J.J.; Memmott, R.M.; Lam, S.; Dennis, P.A. The chemopreventive agent myoinositol inhibits akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in bronchial lesions from heavy smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2009, 2, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassie, F.; Melkamu, T.; Endalew, A.; Upadhyaya, P.; Luo, X.; Hecht, S.S. Inhibition of lung carcinogenesis and critical cancer-related signaling pathways by n-acetyl-s-(n-2-phenethylthiocarbamoyl)-l-cysteine, indole-3-carbinol and myo-inositol, alone and in combination. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witschi, H.; Espiritu, I.; Uyeminami, D. Chemoprevention of tobacco smoke-induced lung tumors in a/j strain mice with dietary myo-inositol and dexamethasone. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Witschi, H.; Espiritu, I.; Ly, M.; Uyeminami, D. The effects of dietary myoinositol on lung tumor development in tobacco smoke-exposed mice. Inhal. Toxicol. 2004, 16, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, S.; McWilliams, A.; LeRiche, J.; MacAulay, C.; Wattenberg, L.; Szabo, E. A phase i study of myo-inositol for lung cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 1526–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unver, N.; Delgado, O.; Zeleke, K.; Cumpian, A.; Tang, X.; Caetano, M.S.; Wang, H.; Katayama, H.; Yu, H.; Szabo, E.; et al. Reduced il-6 levels and tumor-associated phospho-stat3 are associated with reduced tumor development in a mouse model of lung cancer chemoprevention with myo-inositol. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.I.; Lee, H.W. A myo-inositol diet for lung cancer prevention and beyond. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S3919–S3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Rojo de la Vega, M.; Chapman, E.; Ooi, A.; Zhang, D.D. The effects of nrf2 modulation on the initiation and progression of chemically and genetically induced lung cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 57, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sova, M.; Saso, L. Design and development of nrf2 modulators for cancer chemoprevention and therapy: A review. Drug Des. Dev. 2018, 12, 3181–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.; Oza, A.M.; Siu, L.L. The statins as anticancer agents. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.; Porter, D.C.; Chen, X.; Herliczek, T.; Lowe, M.; Keyomarsi, K. Lovastatin-mediated g1 arrest is through inhibition of the proteasome, independent of hydroxymethyl glutaryl-coa reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 7797–7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.C.; Yang, T.Y.; Hsu, Y.P.; Hao, W.R.; Kao, P.F.; Sung, L.C.; Chen, C.C.; Wu, S.Y. Statins dose-dependently exert a chemopreventive effect against lung cancer in copd patients: A population-based cohort study. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 59618–59629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khurana, V.; Bejjanki, H.R.; Caldito, G.; Owens, M.W. Statins reduce the risk of lung cancer in humans: A large case-control study of us veterans. Chest 2007, 131, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yi, L.; Chen, S. Can statins reduce risk of lung cancer, especially among elderly people? A meta-analysis. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2013, 25, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Zhang, K.; Gu, L. Angiotensin receptor blockers (arbs) reduce the risk of lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 12656–12660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pasternak, B.; Svanstrom, H.; Callreus, T.; Melbye, M.; Hviid, A. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer. Circulation 2011, 123, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, L.; Assimes, T.L.; Yin, H.; Bartels, D.B.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Suissa, S. Long-term use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, B.M.; Filion, K.B.; Yin, H.; Sakr, L.; Udell, J.A.; Azoulay, L. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and risk of lung cancer: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2018, 363, k4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franses, J.W.; Baker, A.B.; Chitalia, V.C.; Edelman, E.R. Stromal endothelial cells directly influence cancer progression. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 66ra65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franses, J.W.; Drosu, N.C.; Gibson, W.J.; Chitalia, V.C.; Edelman, E.R. Dysfunctional endothelial cells directly stimulate cancer inflammation and metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, A.; Pai, R.C.; Fong, S.; Leung, S.; Lawrence, D.A.; Marsters, S.A.; Blackie, C.; Chang, L.; McMurtrey, A.E.; Hebert, A.; et al. Safety and antitumor activity of recombinant soluble apo2 ligand. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 104, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, S.K.; Harris, L.A.; Xie, D.; Deforge, L.; Totpal, K.; Bussiere, J.; Fox, J.A. Preclinical studies to predict the disposition of apo2l/tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in humans: Characterization of in vivo efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety. J. Pharm. Exp. 2001, 299, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tolcher, A.W.; Mita, M.; Meropol, N.J.; von Mehren, M.; Patnaik, A.; Padavic, K.; Hill, M.; Mays, T.; McCoy, T.; Fox, N.L.; et al. Phase i pharmacokinetic and biologic correlative study of mapatumumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody with agonist activity to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor-1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, S.J.S.; Lewis, K.E.; Huws, S.A.; Hegarty, M.J.; Lewis, P.D.; Pachebat, J.A.; Mur, L.A.J. A pilot study using metagenomic sequencing of the sputum microbiome suggests potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Gao, R.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Guo, H.; Cheng, J.; et al. Discovery and validation of potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 3111–3122. [Google Scholar]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillere, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of pd-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, O.V.; Romashin, D.; Zborovskaya, I.B.; Davydov, M.M.; Shogenov, M.S.; Gratchev, A. Human lung microbiome on the way to cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 1394191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, A.; Sabharwal, A.; Violante, T.; Manuballa, S.; Genco, R.; Patnaik, S.; Yendamuri, S. The microbiome and lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, V.C. Quorum sensing inhibitors: An overview. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasky, T.M.; White, E.; Chen, C.L. Long-term, supplemental, one-carbon metabolism-related vitamin b use in relation to lung cancer risk in the vitamins and lifestyle (vital) cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3440–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Affected Pathways | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Phytochemicals | Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-oxidant | Inhibition of PKA-induced signaling and PKA-induced generation of ROS Suppression of ROS production and modulation of insulin-like growth factor -I/pathway | Resveratrol (grape) Caffeic acid Curcumin Plumbagin Honokiol Lycopene (tomato) | Multiple cancer lines [103] in vitro Smoke-induced carcinogenesis model in ferrets [117] |

| Modulation of invasion and migration of cancer cells | Inhibition of MMP-2 | Plumbagin | Human A549 lung cancer cells [104] |

| Modulation of the immune system | Potentiation of NK cell lysis via NKG2D pathway | Resveratrol | Clinical trial [118] |

| Induction of apoptosis | Reduction of the mitochondrial membrane potential and release of cytochrome c Induction of apoptosisi and cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase Downregulation of Bcl-2 and NF-κB pathway Modulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway | Polyphyllin D (Chinese medical herb Paris polyphylla) Ganoderic acid T (Chinese medicine herb Ganoderma lucidium) Green tea polyphenols (EGCG) Green tea polyphenols (EGCG) Polyphyllin VII (Chinese medical herb Paris polyphylla) | Lewis lung cancer cells [119] in vitro NSCLC (A549, NCI-H460) [120] cells in vitro Tobacco carcinogen-induced (NKK-induced) lung tumors in A/J mice [121] A549 human lung cancer in vitro [122] |

| Alteration of epigenetic alterations in cells | Modulation of DNA methylation and chromatin modeling | Green tea polyphenols | H460 lung cancer cell line [123] A549 and H460 human lung cancer cell lines in vitro and lung cancer xenograft of A549 in BALB/c nude mice models in vivo [124] |

| Inflammation | Modulation of the IL-10 and TGF-β | Water extract of ginseng and astragalus | A549 cells in vitro and LLC-allografted mice model [125] |

| Glucose Metabolism | Inhibition of isoform 5 of lactate dehydrogenase | Crocetin (saffron) | human A549 lung cancer cells [126] in vitro |

| Class of Chemopreventive Agents | Chemopreventive Agent | Trial | Suboplulation of Patients | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamins and minerals | ⍺-tocopherol, β-carotene | ATBC Study (Finland, 1994) | 29, 133 male smokers (≥ 5 cigarettes/day) | 17% increase in the lung cancer rate and 8% increase in the overall death rate [91]. The follow-up study showed reduction in the risk of those who quitted smoking [92]. |

| β-carotene, retinol | CARET Study (USA, 1985) | 18,344 current and ex-smokers, male and female; workers with history of asbestos exposure | Study was stopped 21 months earlier due to the higher incidence of lung cancer, higher rate of cardiovascular-related, mortality and overall mortality [93]. | |

| β-carotene | Physician’s Health Study (USA, 1982) | 22,071 male physicians, current smokers (11%) or former smokers (39%) | After 12 years, no effect was observed on any of the outcomes (malignant neoplasia, cardiovascular diseases, and death from all causes) [95] | |

| Selinium | The Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Trial | 1312 participants | Lung cancer was the secondary end point, with the pronounced benefit observed only in the subgroup with the low baseline of Se in serum [101]. | |

| Selinium | Secondary lung tumor prevention | 1772 patients with resected stage I non-small cell lung cancer | No chemoprevention benefit was observed [102] | |

| Phytochemicals | Green tea or polyphenon E | NCT00363805 (USA, 2004) | 195 patients, current or ex-smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | No results were published |

| Green tea, black tea | NCT02719860 High Tea Consumption on Smoking Related Oxidative Stress (USA, 2004) | 154 participants, current and ex-smokers | No results were published | |

| Glucobrassicin-rich Brussels sprouts | NCT0299939 Glucobrassicin-Brussel Sprout Effect on D10 Phe Metabolism (USA, 2016) | 48 participants, current and ex-smokers | Ongoing study | |

| Sulforaphane | NCT03232138 Clinical Trial of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention With Sulforaphane in Former Smokers | 72 participants, current and ex-smokers | Ongoing study | |

| Anti-innflammatory agents | Low-does aspirin (100 mg daily) | Women’s Health Study (USA, 1993) | 39,876 healthy female health professionals | No effect on lung cancer incidents [133] |

| NSAID’s and vitamin B | The VITamins And Lifestyle (Vital) Study | 77,738 men and women | No effect of pre-diagnostic use of aspirin on the survival rate in patients with lung cancer [202]. High use of ibuprofen was associated with the 64% increase in lung cancer mortality. | |

| Low (200 mg daily) and high (400 mg twice a day) doses of celecoxib | Biological activity of celecoxib in the bronchial epithelium of current and former smokers (USA, 2010) | 204 patients, smokers and former smokers | High-dose showed statistically significant reduction in Ki-67 expression in smokers (by 1.10%) and in former smokers (by 3.85%) [131] | |

| Celecoxib (400 mg daily) | Lung cancer chemoprevention with celecoxib in former smokers (USA, 2010) | 137 participants, former smokers (≥ 30-pack-years of smoking; ≥ of sustained abstinence of smoking) | Significant reduction in Ki-67 expression (up to 34%) in the celecoxib-arm. Beneficial results were linked with the higher levels of PGE2 in responders [82]. | |

| Iloprost | Effect of oral iloprost on endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers(USA, 2012) | 152 subjects with the sputum cytologic atypia (current and former smokers) | Significant improvement in biopsy data for former smokers, no effect was observed for current smokers [137]. | |

| Budenoside(1600μg daily for 6 months) | A randomized phase IIb trial of pulmicort turbuhaler (budesonide) in people with dysplasia of the bronchial epithelium. | 112 smokers with one or more sites of bronchial dysplasia | In smokers, inhaled budenoside showed no effect on regression of bronchial dysplastic lesions or prevention of new lesions [142]. | |

| Budenoside(800μg twice daily for 12 months) | Randomized phase II trial of inhaled budesonide versus placebo in high-Risk individuals with CT screen–detected lung nodules (USA, 2011) | 202 subjects, current and former smokers with CT-detected lung nodules that were persistent for at least 1 year | No effect was detected on lung nodules sizes, although per-lesion analysis showed effect on a regression of existing target nodules. No effect was observed for peripheral nodule sizes [143]. | |

| Triamcinolone, beclomethasone, flunisolide, fluticasone | Inhaled corticosteroids and risk of lung cancer among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (USA, 2001) | 10,474 subjects with a diagnosis of COPD and no history of lung cancer | A dose-response decrease in risk of lung cancer was observed [144]. | |

| Fluticasone and budenoside | Effect of inhaled corticosteroids against lung cancer in female patients with COPD: a nationwide population-based cohort study (Taiwan, 2009) | 13,868 female COPD patients | A reduction of 1.5 fold in lung cancer incidence rate was observed in patients treated with the inhaled corticosteroids [145]. | |

| PPARγ agonists | Pioglitazone | A Randomized Phase II Trial of Pioglitazone for Lung Cancer Chemoprevention in High-Risk Current and Former Smokers (USA, 2019) | 92 subjects with the sputum cytologic atypia (current and former smokers) | Slight improvement in worst biopsy scores, dysplasia index, and average score was observed in former smokers. No protective effect was observed in current smokers [155]. |

| Modulators of mTOR pathways | Myo-inositol (18 g daily for 3 months) | A phase I study of myo-inositol for lung cancer chemoprevention (Canada, 2006) | 26 participants, smokers (≥ 30-pack-years of smoking) with one or more sites of bronchial dysplasia. Dose -escalation study had 16 participants, chemoprevention study was done in a group of 10 patients | Significant regression of dysplastic lesions was observed [177]. |

| Statins | Lovastatin, fluvastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin, and pravastatin | A population-based cohort study to evaluate effect of stating against lung cancer in COPD patients (Taiwan, 2012) | 43,802 COPD patients | Statins, except lovastatin and fluvastatin, produce dose-dependent chemopreventive effect in studies COPD group of patients [184]. |

| Statins | A retrospective case-control study of US veterans evaluation the effect of statins on the risk of lung cancer in humans (USA, 2004) | 483,733 subjects | Statins showed protective effect against the development of lung cancer [185]. | |

| Antihypertensive agents | Angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel blockers. | A retrospective cohort study to analyze an association between the use of angiotensin receptor blockers and cancer (UK, 2010) | 1,165,781 patients that were prescribed antihypertensive agents | Angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics beta-blockers had no effect on the rate of lung cancer incidences. However, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel blockers were associated with the higher incidences of lung cancer [189]. |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | A retrospective nationwide cohort study: use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer (Denmark, 2006) | 107,466 ARB users (≥ 35 years) | No effect of Angiotensin receptor blockers on lung cancer incidences [188]. | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers | Population based cohort study to analyze an association between the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cancer (UK, 2016) | 992,061 patients newly treated with any hypertensive agents. | Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors was associated with the higher incidences of lung cancer [190]. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ashraf-Uz-Zaman, M.; Bhalerao, A.; Mikelis, C.M.; Cucullo, L.; German, N.A. Assessing the Current State of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention: A Comprehensive Overview. Cancers 2020, 12, 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051265

Ashraf-Uz-Zaman M, Bhalerao A, Mikelis CM, Cucullo L, German NA. Assessing the Current State of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention: A Comprehensive Overview. Cancers. 2020; 12(5):1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051265

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshraf-Uz-Zaman, Md, Aditya Bhalerao, Constantinos M. Mikelis, Luca Cucullo, and Nadezhda A. German. 2020. "Assessing the Current State of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention: A Comprehensive Overview" Cancers 12, no. 5: 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051265

APA StyleAshraf-Uz-Zaman, M., Bhalerao, A., Mikelis, C. M., Cucullo, L., & German, N. A. (2020). Assessing the Current State of Lung Cancer Chemoprevention: A Comprehensive Overview. Cancers, 12(5), 1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051265