Cognitive Functions in Repeated Glioma Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

2. Results

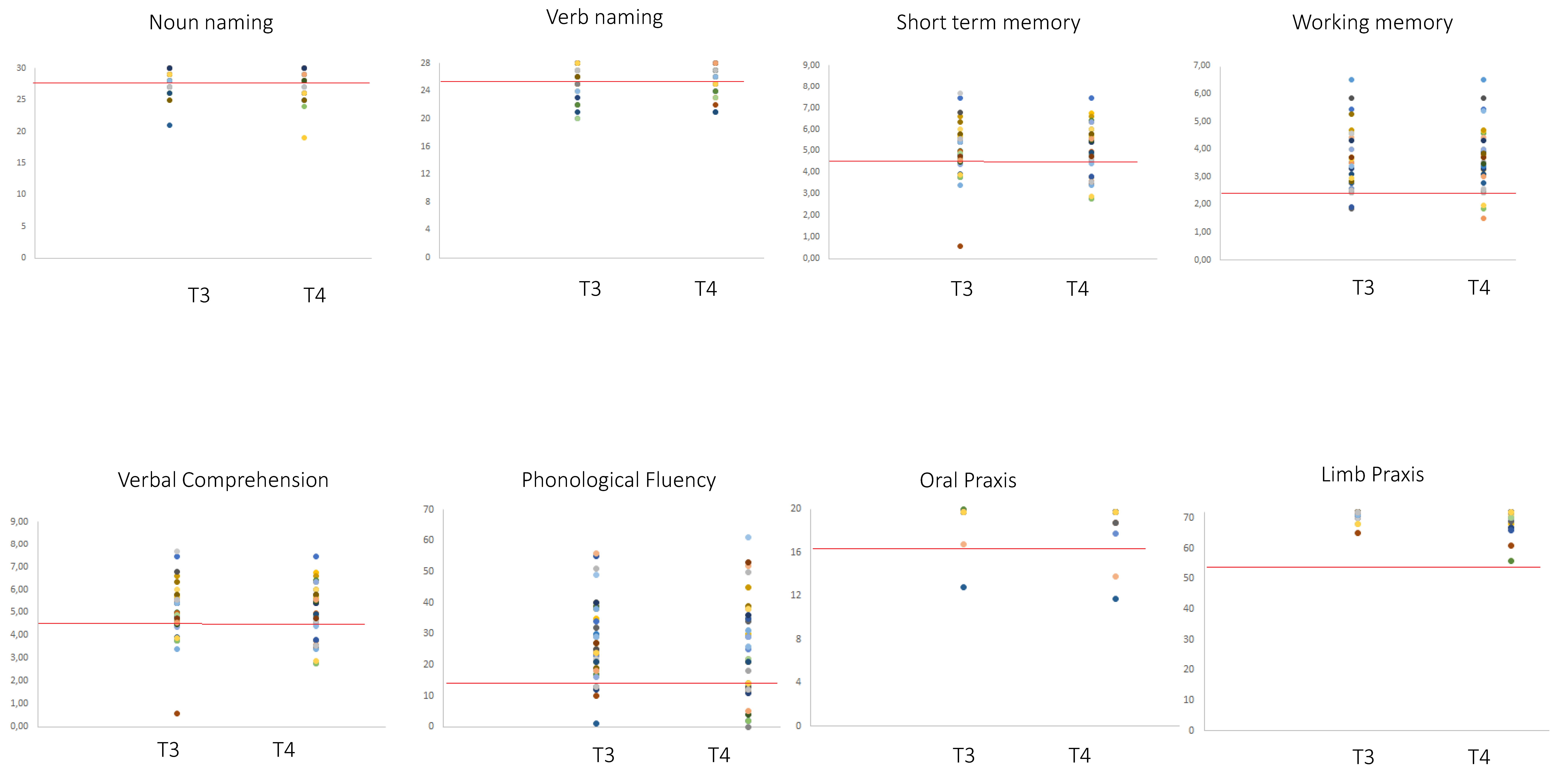

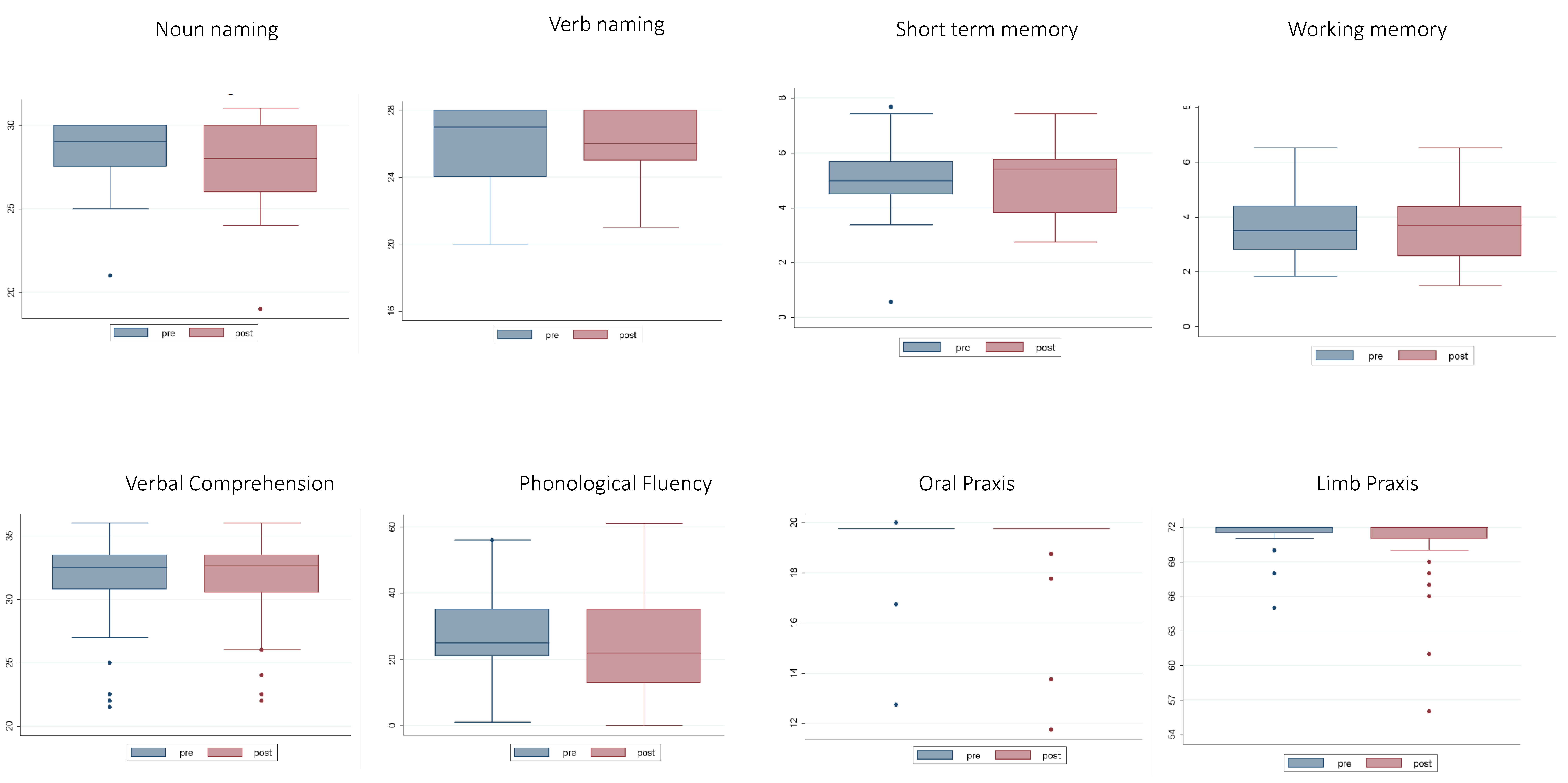

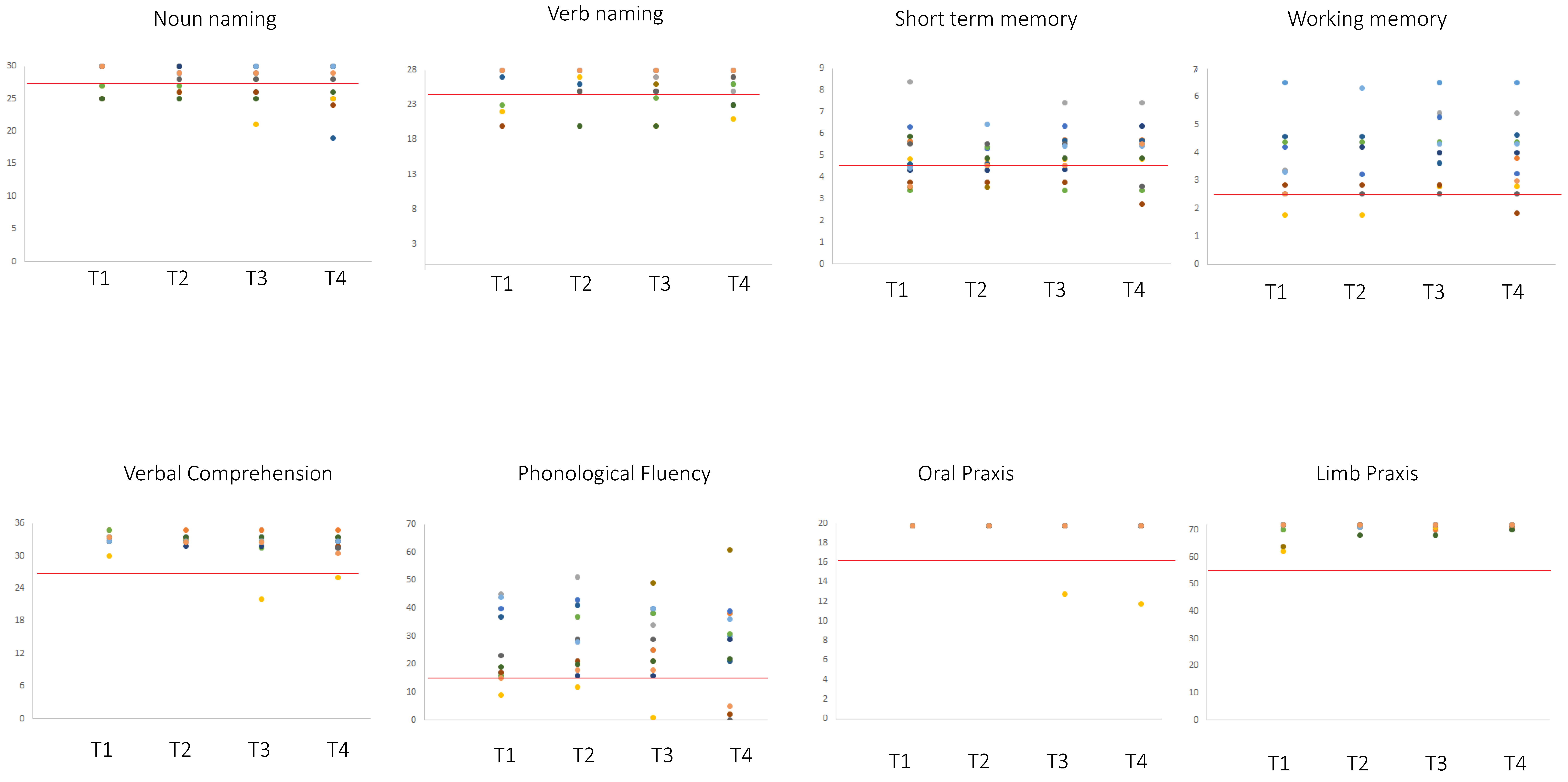

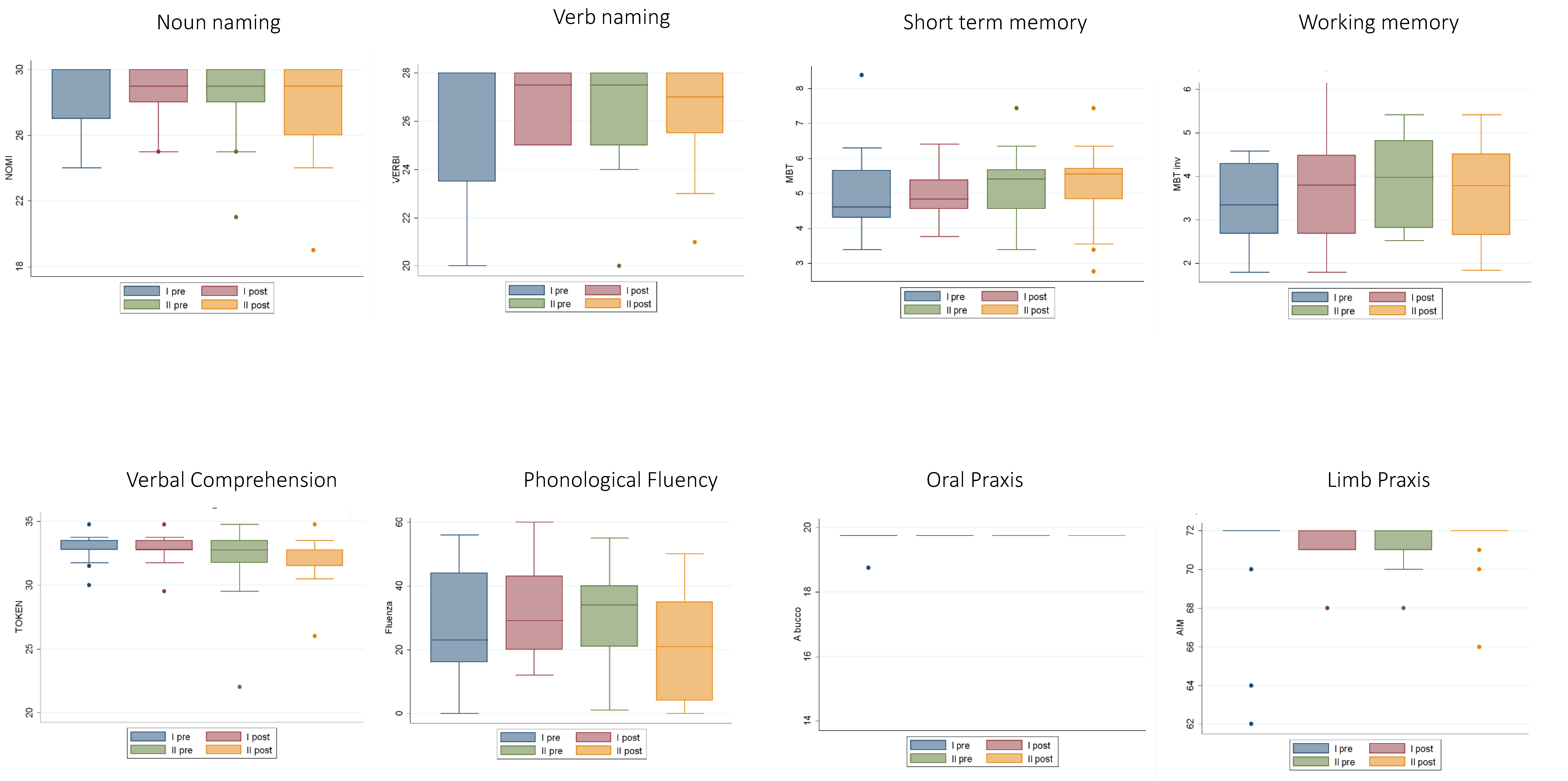

2.1. Neuropsychological Data

2.2. Radiotherapy

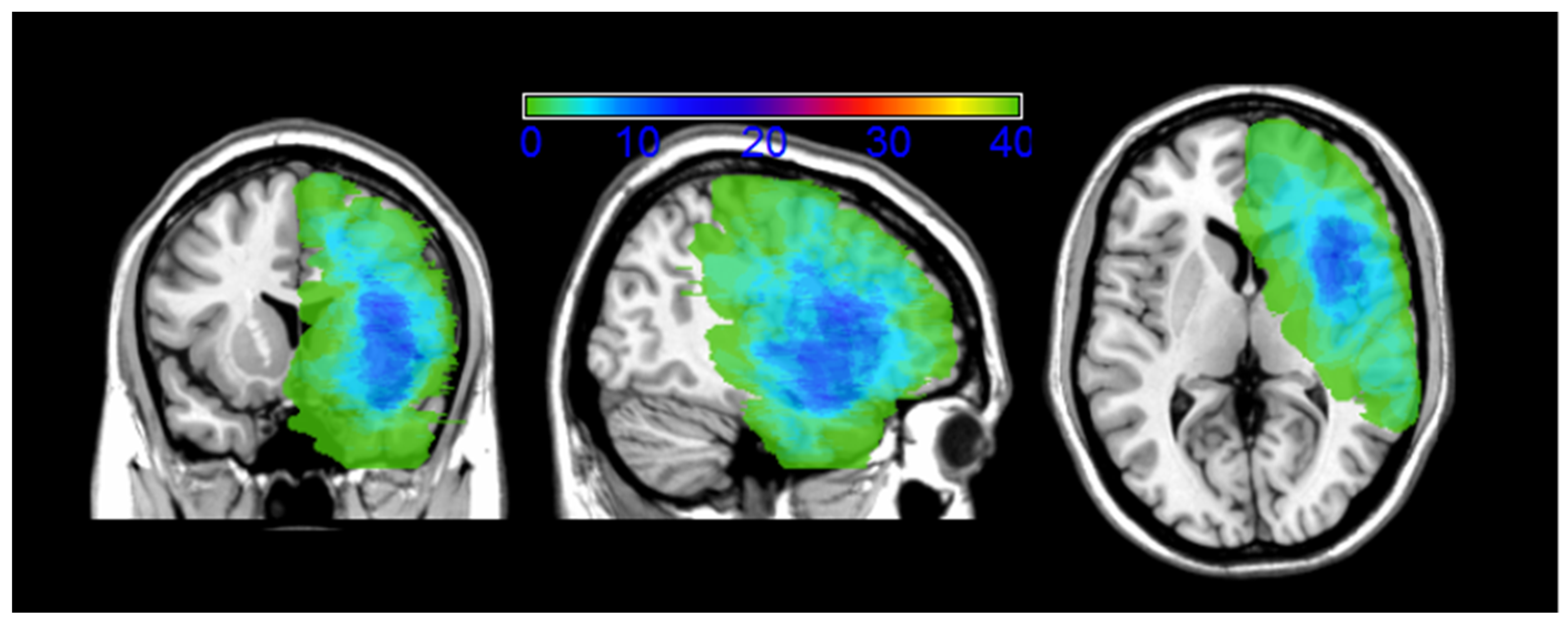

2.3. MRI Structural Data Analysis

2.4. Intraoperative Findings in Recurrence Surgery

2.5. Extent of Resection

2.6. Overall Survival

2.7. Correlation Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Neuropsychological Testing

4.2. MRI Structural Data

4.3. Awake Surgery

4.4. Radiotherapy

4.5. Statistical Analysis of Neuropsychological Data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ius, T.; Isola, M.; Budai, R.; Pauletto, G.; Tomasino, B.; Fadiga, L.; Skrap, M. Low-grade glioma surgery in eloquent areas: Volumetric analysis of extent of resection and its impact on overall survival. A single-institution experience in 190 patients—Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 117, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugdale, E.; Gerrard, G. Low-grade gliomas in adults. Cancer Med. 2006, 3, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rezvan, A.; Christine, D.; Christian, H.; Olga, Z.; Lutz, E.; Marius, H.; Stephanie, C.; Christel, H.M.; Rainer, W.C.; Andreas, U. Long-term outcome and survival of surgically treated supratentorial low-grade glioma in adult patients. Acta Neurochir. (Wien.) 2009, 151, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffau, H.; Taillandier, L. New concepts in the management of diffuse low-grade glioma: Proposal of a multistage and individualized therapeutic approach. Neuro Oncol. 2015, 17, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myrmel, K.S. Comparison of a Strategy Favoring Early Surgical Resection vs a Strategy Favoring Watchful Waiting in Low-Grade Gliomas. JAMA 2012, 308, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar]

- McGirt, M.J.; Chaichana, K.L.; Attenello, F.J.; Weingart, J.D.; Than, K.; Burger, P.C.; Olivi, A.; Brem, H.Q.-H.A. Extent of surgical resection is independently associated with survival in patients with hemispheric infiltrating low-grade gliomas. Neurosurgery 2008, 63, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomas, D.A.; Laack, N.N.I.; Rao, R.D.; Meyer, F.B.; Shaw, E.G.; Neill, B.P.O.; Giannini, C.; Brown, P.D. Intracranial low-grade gliomas in adults: 30-year experience with long-term follow-up at Mayo Clinic. Neuro Oncol. 2009, 11, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.S.; Chang, E.F.; Lamborn, K.R.; Chang, S.M.; Prados, M.D.; Cha, S.; Tihan, T.; Vandenberg, S.; Mcdermott, M.W.; Berger, M.S. Role of Extent of Resection in the Long-Term Outcome of Low-Grade Hemispheric Gliomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. Long-term outcomes after supratotal resection of diffuse low-grade gliomas: A consecutive series with 11-year follow-up. Acta Neurochir. (Wien.) 2016, 158, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumert, B.G.; Stupp, R. Low-grade glioma: A challenge in therapeutic options: The role of radiotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ius, T.; Pauletto, G.; Cesselli, D.; Isola, M.; Turella, L.; Budai, R.; Demaglio, G.; Eleopra, R.; Fadiga, L.; Lettieri, C.; et al. Second Surgery in Insular Low-Grade Gliomas. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 497610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.S.; Leyrer, C.M.; Parsons, M.; Suh, J.H.; Chao, S.T.; Yu, J.S.; Kotecha, R.; Jia, X.; Peereboom, D.M.; Prayson, R.A.; et al. Risk Factors for Malignant Transformation of Low-Grade Glioma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 100, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotta, J.M.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Reis, R.C.; Botelho, R.V. Malignant transformation of low-grade gliomas in patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2017, 117, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdańska, M.U.; Bodnar, M.; Piotrowska, M.J.; Murek, M.; Schucht, P.; Beck, J.; Martínez-González, A.; Pérez-García, V.M. A mathematical model describes the malignant transformation of low grade gliomas: Prognostic implications. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chiang, G.C.-Y.; Magge, R.S.; Fine, H.A.; Ramakrishna, R.; Chang, E.W.; Pulisetty, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Kovanlikaya, I. Texture analysis on conventional MRI images accurately predicts early malignant transformation of low-grade gliomas. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 2751–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, R.; Hebb, A.; Barber, J.; Rostomily, R.; Silbergeld, D. Outcomes in Reoperated Low-Grade Gliomas. Neurosurgery 2015, 77, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.H.; Berger, M.S.; Lamborn, K.R.; Aldape, K.; McDermott, M.W.; Prados, M.D.; Chang, S.M. Repeated operations for infiltrative low-grade gliomas without intervening therapy. J. Neurosurg. 2003, 98, 1165–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamisch, C.; Ruge, M.; Kellermann, S.; Kohl, A.C.; Duval, I.; Goldbrunner, R.; Grau, S.J. Impact of treatment on survival of patients with secondary glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 133, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. Brain plasticity and tumors. In Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery; Pickard, J.D., Akalan, N., Di Rocco, C., Dolenc, V.V., Antunes, J.L., Mooij, J.J.A., Schramm, J., Sindou, M., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2008; pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-3-211-72283-1. [Google Scholar]

- Duffau, H. Brain plasticity: From pathophysiological mechanisms to therapeutic applications. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 13, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, D.G.; Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Perry, D.W.; Berger, M.S. Intraoperative mapping during repeat awake craniotomy reveals the functional plasticity of adult cortex. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H.; Capelle, L. Preferential brain locations of low-grade gliomas: Comparison with glioblastomas and review of hypothesis. Cancer 2004, 100, 2622–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffau, H.; Capelle, L.; Denvil, D.; Sichez, N.; Gatignol, P.; Lopes, M.; Mitchell, M.C.; Sichez, J.P.; Van Effenterre, R. Functional recovery after surgical resection of low grade gliomas in eloquent brain: Hypothesis of brain compensation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffau, H.; Lopes, M.; Arthuis, F.; Bitar, A.; Sichez, J.P.; Van Effenterre, R.; Capelle, L. Contribution of intraoperative electrical stimulations in surgery of low grade gliomas: A comparative study between two series without (1985-96) and with (1996–2003) functional mapping in the same institution. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juratli, T.A.; Kirsch, M.; Geiger, K.; Klink, B.; Leipnitz, E.; Pinzer, T.; Soucek, S.; Schrok, E.; Schackert, G.; Krex, D. The prognostic value of IDH mutations and MGMT promoter status in secondary high-grade gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2012, 110, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thon, N.; Eigenbrod, S.; Kreth, S.; Lutz, J.; Tonn, J.C.; Kretzschmar, H.; Peraud, A.; Kreth, F.W. IDH1 mutations in grade II astrocytomas are associated with unfavorable progression-free survival and prolonged postrecurrence survival. Cancer 2012, 118, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.; Tzarfati, G.; Costa, M.; Serafimova, M.; Korn, A.; Vendrov, I.; Alfasi, T.; Krill, D.; Aviram, D.; Ben Moshe, S.; et al. Incidence and impact of stroke following surgery for low-grade gliomas. J. Neurosurg. JNS 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppstrom, T.J.; Singh, R.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.F.; Magge, R.; Ramakrishna, R. Repeat surgery for recurrent low-grade gliomas should be standard of care. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2016, 151, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonski, M.; Taillandier, L.; Herbet, G.; Maldonado, I.L.; Beauchesne, P.; Fabbro, M.; Campello, C.; Gozé, C.; Rigau, V.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; et al. Combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection as a new strategy for WHO grade II gliomas: A study of cognitive status and quality of life. J. Neurooncol. 2012, 106, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, J.; Taillandier, L.; Moritz-gasser, S.; Gatignol, P.; Duffau, H. Re-operation is a safe and effective therapeutic strategy in recurrent WHO grade II gliomas within eloquent areas. Acta Neurochir. (Wien.) 2009, 151, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeckle, K.A.; Decker, P.A.; Ballman, K.V.; Flynn, P.J.; Giannini, C.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Jenkins, R.B.; Buckner, J.C. Transformation of low grade glioma and correlation with outcome: An NCCTG database analysis. J. Neurooncol. 2011, 104, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuya, Y.; Ikuta, S.; Maruyama, T.; Nitta, M.; Saito, T.; Tsuzuki, S.; Chernov, M.; Kawamata, T.; Muragaki, Y. Tumor recurrence patterns after surgical resection of intracranial low-grade gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 2019, 144, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, C.G.; Walker, D.G.; Miller, D.M.; Butte, P.; Morrison, B.; Kittle, D.S.; Hansen, S.J.; Nufer, K.L.; Byrnes-Blake, K.A.; Yamada, M.; et al. Phase 1 Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Fluorescence Imaging Study of Tozuleristide (BLZ-100) in Adults With Newly Diagnosed or Recurrent Gliomas. Neurosurgery 2019, 85, E641–E649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonski, M.; Pallud, J.; Gozé, C.; Mandonnet, E.; Rigau, V.; Bauchet, L.; Fabbro, M.; Beauchesne, P.; Baron, M.H.; Fontaine, D.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may optimize the extent of resection of World Health Organization grade II gliomas: A case series of 17 patients. J. Neurooncol. 2013, 113, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Niu, X.; Gan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Mao, Q. Clinical and Pathologic Features and Prognostic Factors for Recurrent Gliomas. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, e21–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, P.; Bernstein, M.; Muller, P.J.; Tucker, W.S. The value of reoperation for recurrent glioblastoma. Can. J. Surg. 1993, 36, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Harsh, G.R.; Levin, V.A.; Gutin, P.H.; Seager, M.; Silver, P.; Wilson, C.B. Reoperation for Recurrent Glioblastoma and Anaplastic Astrocytoma. Neurosurgery 1987, 21, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmurget, M.; Bonnetblanc, F.; Duffau, H. Contrasting acute and slow-growing lesions: A new door to brain plasticity. Brain 2007, 130, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. Lessons from brain mapping in surgery for low-grade glioma: Insights into associations between tumour and brain plasticity. Lancet Neurol. 2005, 4, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, F.; Palese, A.; Del Missier, F.; Moreale, R.; Ius, T.; Shallice, T.; Fabbro, F.; Skrap, M. Long-Term Cognitive Functioning and Psychological Well-Being in Surgically Treated Patients with Low-Grade Glioma. World Neurosurg. 2017, 103, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, M.; Costa, A.; Caltagirone, C.; Carlesimo, G.A. Forward and backward span for verbal and visuo-spatial data: Standardization and normative data from an Italian adult population. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 34, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, M.; Costa, A.; Caltagirone, C.; Carlesimo, G.A. Erratum to: Forward and backward span for verbal and visuo-spatial data: Standardization and normative data from an Italian adult population. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 36, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novelli, G.; Papagno, C.; Capitani, E.; Laiacona, M.; Vallar, G.; Cappa, S.F. Tre test clinici di ricerca e produzione lessicale. Taratura su sogetti normali. Arch. Psicol. Neurol. Psichiatr. 1986, 47, 477–506. [Google Scholar]

- De Renzi, E.; Motti, F.; Nichelli, P. Imitating Gestures: A Quantitative Approach to Ideomotor Apraxia. Arch. Neurol. 1980, 37, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinnler, M.; Tognoni, G. Standardizzazione e validazione di test neuropsicologici. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1987, 8, 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Miceli, G.; Laudanna, A.; Burani, C. Batteria per l’analisi dei Deficit Afasici. B. A. D. A. (B. A. D. A.: A Battery for the Assessment of Aphasic Disorders). Roma Cepsag 1994. Available online: https://www.iris.unisa.it/handle/11386/3828878?mode=full.19 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- De Renzi, E.; Faglioni, P. Normative Data and Screening Power of a Shortened Version of the Token Test. Cortex 1978, 14, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.S. Lesions in functional (“eloquent”) cortex and subcortical white matter. Clin. Neurosurg. 1994, 41, 444–463. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.S.; Ojemann, G.A. Intraoperative brain mapping techniques in neuro-oncology. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 1992, 58, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojemann, G.; Ojemann, J.; Lettich, E.; Berger, M. Cortical language localization in left, dominant hemisphere. J. Neurosurg. 1989, 71, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrap, M.; Marin, D.; Ius, T.; Fabbro, F.; Tomasino, B. Brain mapping: A novel intraoperative neuropsychological approach. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 125, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrap, M.; Mondani, M.; Tomasino, B.; Weis, L.; Budai, R.; Pauletto, G.; Eleopra, R.; Fadiga, L.; Ius, T. Surgery of insular nonenhancing gliomas: Volumetric analysis of tumoral resection, clinical outcome, and survival in a consecutive series of 66 cases. Neurosurgery 2012, 70, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ius, T.; Pignotti, F.; Della Pepa, G.M.; Bagatto, D.; Isola, M.; Battistella, C.; Gaudino, S.; Pegolo, E.; Chiesa, S.; Arcicasa, M.; et al. Glioblastoma: From volumetric analysis to molecular predictors. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| P# | Gender | Age | S | Site Surgery | H | Hist | EOR | RT Post 2nd Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 33 | 13 | F-T-I | LH | LGG | 66 | V |

| 2 | M | 32 | 8 | F-P | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 3 | M | 35 | 13 | T-I | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 4 | F | 52 | 13 | F-P | LH | LGG | 85 | V |

| 5 | M | 23 | 13 | F | LH | LGG | 100 | X |

| 6 | M | 40 | 13 | T | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 7 | F | 56 | 13 | F-I | LH | HGG | 100 | X |

| 8 | M | 24 | 13 | T-P | LH | HGG | 100 | X |

| 9 | M | 36 | 8 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 100 | X |

| 10 | M | 30 | 18 | F | LH | LGG | 90 | X |

| 11 | F | 37 | 18 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 85 | V |

| 12 | M | 41 | - | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 85 | V |

| 13 | M | 20 | 11 | T-P | LH | LGG | 65 | X |

| 14 | M | 49 | 17 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 90 | V |

| 15 | M | 45 | 18 | F | LH | LGG | 90 | X |

| 16 | M | 44 | 13 | T | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 17 | M | 35 | 8 | F-P | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 18 | F | 34 | 8 | F-P | LH | HGG | 100 | X |

| 19 | F | 38 | 18 | F-P | LH | LGG | 85 | X |

| 20 | M | 48 | 8 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 21 | M | 37 | 13 | F-T-I | LH | LGG | 90 | X |

| 22 | F | 17 | 10 | F | LH | LGG | 85 | X |

| 23 | M | 39 | 8 | F | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 24 | F | 66 | 5 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 25 | M | 45 | 18 | F-T-I | LH | LGG | 70 | X |

| 26 | M | 47 | 18 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 27 | M | 57 | 18 | T | LH | HGG | X | |

| 28 | M | 15 | 10 | F-I | LH | LGG | 100 | X |

| 29 | M | 29 | 18 | F-I | LH | LGG | 100 | X |

| 30 | M | 32 | 5 | F | LH | HGG | 84 | X |

| 31 | M | 36 | 5 | F | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 32 | F | 48 | 13 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 50 | V |

| 33 | M | 33 | 8 | F-I | LH | LGG | 80 | V |

| 34 | M | 36 | 8 | F-I | LH | HGG | 85 | X |

| 35 | M | 34 | 18 | F-T-I | LH | LGG | 85 | X |

| 36 | F | 28 | 13 | F-T-I | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| 37 | M | 18 | 12 | T | LH | LGG | 100 | X |

| 38 | F | 34 | 13 | F-I | LH | LGG | 92 | X |

| 39 | F | 35 | 13 | F-I | LH | LGG | 90 | X |

| 40 | F | 47 | 8 | T | LH | HGG | 100 | V |

| Number of Patients within the Normal Range | Level of Performance of Patients Below the Normal Range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | T3 | T4 | T3 vs. T4 McNemar | T3 | T4 | Cut-offs |

| STM | 31/38 | 28/38 (4/38 w; 1/38 i) | p = 0.375, n.s. | 3.05 ± 1.4 | 3.39 ± 0.41 | 4.26 |

| o_PRAXIS | 40/40 | 40/40 | - | - | - | - |

| IMA | 38/38 | 38/38 | - | - | - | - |

| Compr | 35/39 | 35/39 (1/39 w, 1/39 i) | p = 1, n.s. | 22.75 ± 1.55 | 23.63 ± 1.80 | 26.26 |

| N_nam | 30/40 | 27/40 (4/40 w, 1/40 i) | p = 0.37, n.s. | 25.60 ± 1.78 | 25.23 ± 2.05 | 28 |

| v_nam | 24/39 | 25/39 (4/39 w, 5/39 i) | p = 1, n.s. | 23.13 ± 1.85 | 23.57 ± 1.45 | 26 |

| WM | 25/31 | 23/31 (4/35w, 2/31 i) | p = 0.68, n.s. | 2.32 ± 0.31 | 2.26 ± 0.39 | 2.65 |

| Ph_Fl | 32/38 | 26/38 (7/38 w, 1/38 i) | p = 0.07, n.s. | 11 ± 5.19 | 8 ± 5.33 | 16 |

| Task | Pre-Surgery | Post-Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| WM | p = 0.28 | p = 0.74 |

| Ph_Fl | p = 0.19 | p = 0.51 |

| Compr | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| o_PRAXIS | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| STM | p = 0.01 | p = 0.2 |

| IMA | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| N_nam | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| v_nam | p < 0.001 | p < 0.01 |

| Task | T3 | T4 | T3 vs. T4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| STM | 5.04 ± 1.23 | 5 ± 1.18 | Z = −0.5, p = 0.59 |

| WM | 3.63 ± 1.13 | 3.63 ± 1.14 | t (30) = −0.18 p = 0.5 |

| IMA | 71.38 ± 1.44 | 70.55 ± 3.28 | Z = 0.84, p = 0.39 |

| N_nam | 28.23 ± 1.9 | 27.95 ± 2.35 | Z = 0.416, p = 0.67 |

| v_nam | 25.79 ± 1.9 | 25.92 ± 2.08 | Z = −0.506, p = 0.612 |

| Compr | 31.37 ± 3.5 | 31.49 ± 3.22 | Z = −0.379, p = 0.750 |

| Ph_Fl | 27.38 ± 12.29 | 25.26 ± 15.07 | t (37) = 0.907, p = 0.18 |

| o_PRAXIS | 19.5 ± 1.19 | 19.30 ± 1.58 | Z = −2.44, p = 0.014 |

| Task | Number of Patients within the Normal Range | Level of Performance of Patients Below the Normal Range | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T1–T4 Cochran’s Q test | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Cut-offs | |

| STM | 10/13 | 12/13 (0 w,2 i) | 11/13 | 10/13 (1w, 0i) | p = 0.299, n.s. | 3.56 ± 0.15 | 3.65 ± 0.84 | 3.58 ± 0.26 | 3.38 ± 0.45 | 4.26 |

| o_PRAXIS | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | - | - | - | - | - | 16 |

| IMA | 17/17 | 17/17 | 17/17 | 17/17 | - | - | - | - | - | 52 |

| Compr | 17/17 | 17/17 | 17/17 | 17/17 | p = 0.391, n.s. | - | - | 22 | 26 | 26.26 |

| N_nam | 12/17 | 14/17 (0w, 2 i) | 13/17 | 12/17 (1w, 0i) | p = 0.468, n.s. | 25.67 ± 1.34 | 25.67 ± 0.58 | 24.50 ± 2.38 | 23.80 ± 2.77 | 28 |

| v_nam | 8/12 | 8/12 (2w, 2 i) | 7/12 | 9/12 (1w, 3 i) | p = 0.801, n.s | 22.25 ± 1.71 | 24 ± 2.5 | 23.43 ± 2.37 | 23 ± 1.63 | 26 |

| WM | 6/8 | 6/8 (0w, o i) | 7/8 | 6/8 (1w, 0 i) | p = 0.732, n.s. | 2.28 ± 0.99 | 2.16 ± 0.99 | 2.28 ± 1.70 | 1.70 ± 0.37 | 2.65 |

| Ph_Fl | 9/13 | 12/13 (o w, 3 i) | 11/13 | 8/13 (3w, 0i) | p = 0.057, n.s. | 10 ± 7.35 | 14 ± 2.83 | 10 ± 7.94 | 2.60 ± 1.95 | 16 |

| Task | Cut-offs | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Repeated Measures ANOVA | Post-Hoc Analyses (Tukey-Corrections) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph_Fl | 16 | 28.92 ± 18.16 | 31.9 ± 15.75 | 30.24 ± 14.69 | 25.06 ± 17.94 | F(3.36) = 8.18, p = 0.0003 | T4 vs. T1. t(12) = −3.09, p = 0.019 T4 vs. T2 t(12) = −4.66, p < 0.001 T4 vs. T3 t(12) = −3.75, p = 0.003 |

| N_nam | 28 | 28.71 ± 2.17 | 28.59 ± 1.66 | 28.06 ± 2.41 | 27.76 ± 3.07 | F(3.48) = 1.13, p = 0.33 | - |

| v_nam | 26 | 26.00 ± 2.92 | 26.36 ± 2.27 | 25.88 ± 2.62 | 26.35 ± 2.15 | F(3.33) = 0.42, p = 0.67 | - |

| Compr | 26.26 | 33.01 ± 1.15 | 32.84 ± 1.09 | 32.00 ± 2.81 | 31.94 ± 1.94 | F(3.48) = 3.06, p = 0.07 | - |

| IMA | 52 | 70.82 ± 3.00 | 71.59 ± 1.00 | 71.53 ± 1.07 | 71.40 ± 1.59 | F(3.42) = 0.67, p = 0.48 | - |

| STM | 4.26 | 4.91 ± 1.36 | 4.81 ± 0.72 | 5.14 ± 0.99 | 5.08 ± 1.23 | F(3.36) = 0.34, p = 0.78 | - |

| WM | 2.65 | 3.61 ± 1.37 | 3.80 ± 1.36 | 3.75 ± 1.38 | 3.75 ± 1.22 | F(3.21) = 0.69, p = 0.568 | - |

| o_PRAXIS | 26 | 19.69 ± 0.25 | 19.75 ± 0.00 | 19.34 ± 1.70 | 19.28 ± 1.94 | F(3.45) = 1, p = 0.33 | - |

| Task | Level of Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | T-Test | RT | No RT |

| STM | t(37) = 0.32, p = 0.74, n.s. | 5.06 ± 1.10 | 4.93 ± 1.28 |

| o_PRAXIS | t(38) = 0.116, p = 0.908, n.s. | 19.32 ± 1.43 | 19.27 ± 1.74 |

| IMA | t(36) = −0.98, p = 0.33, n.s. | 70 ± 3.99 | |

| Compr | t(38) = −0.53, p = 0.59, n.s. | 31.20 ± 3.42 | 31.75 ± 3.11 |

| N_nam | t(38) = −0.67, p = 0.504, n.s. | 27.68 ± 2,75 | 28.19 ± 1.97 |

| v_nam | t(37) = −1.02, p = 0.314, n.s. | 25.56 ± 2,09 | 26.24 ± 2.07 |

| WM | t(33) = 0.704, p = 0.48, n.s. | 3.78 ± 1.28 | 3.504 ± 1.04 |

| Ph_Fl | t(37) = 0.05, p = 0.96, n.s. | 25.39 ± 13.41 | 25.14 ± 16.70 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Capo, G.; Skrap, M.; Guarracino, I.; Isola, M.; Battistella, C.; Ius, T.; Tomasino, B. Cognitive Functions in Repeated Glioma Surgery. Cancers 2020, 12, 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051077

Capo G, Skrap M, Guarracino I, Isola M, Battistella C, Ius T, Tomasino B. Cognitive Functions in Repeated Glioma Surgery. Cancers. 2020; 12(5):1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCapo, Gabriele, Miran Skrap, Ilaria Guarracino, Miriam Isola, Claudio Battistella, Tamara Ius, and Barbara Tomasino. 2020. "Cognitive Functions in Repeated Glioma Surgery" Cancers 12, no. 5: 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051077

APA StyleCapo, G., Skrap, M., Guarracino, I., Isola, M., Battistella, C., Ius, T., & Tomasino, B. (2020). Cognitive Functions in Repeated Glioma Surgery. Cancers, 12(5), 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12051077