HNRNPL Restrains miR-155 Targeting of BUB1 to Stabilize Aberrant Karyotypes of Transformed Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

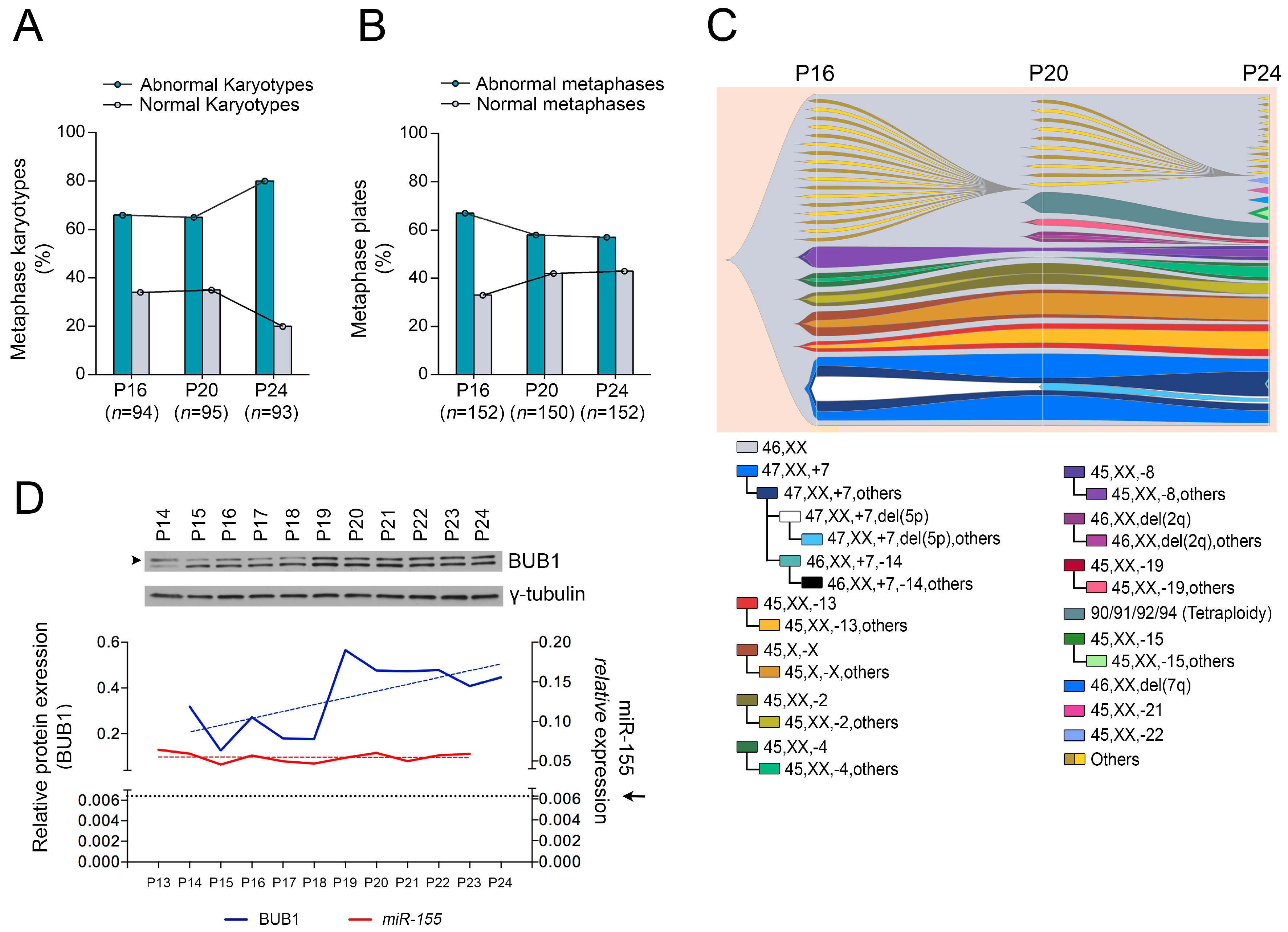

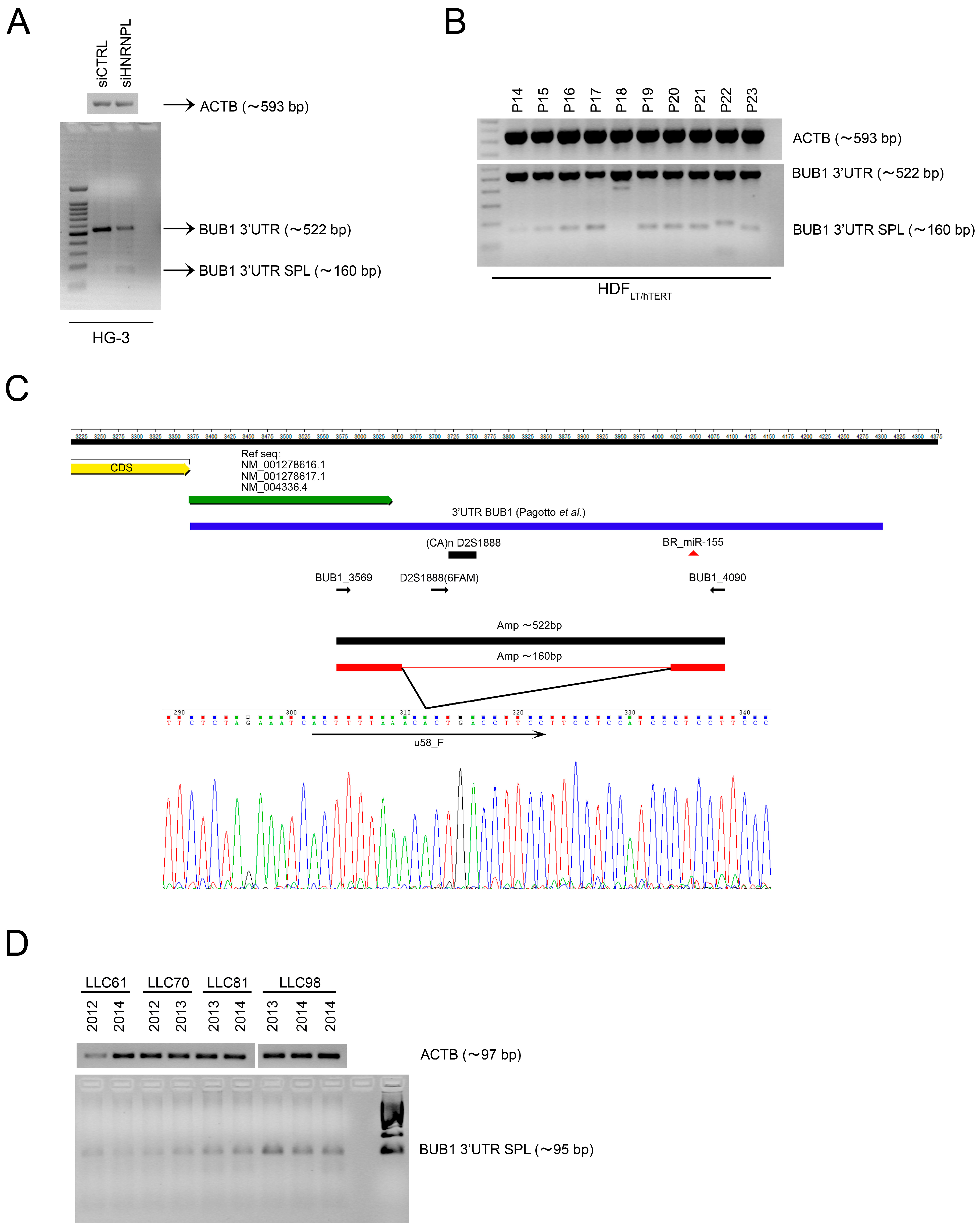

2.1. Role of miR-155 in Advanced Passages of Immortalized HDF Cells

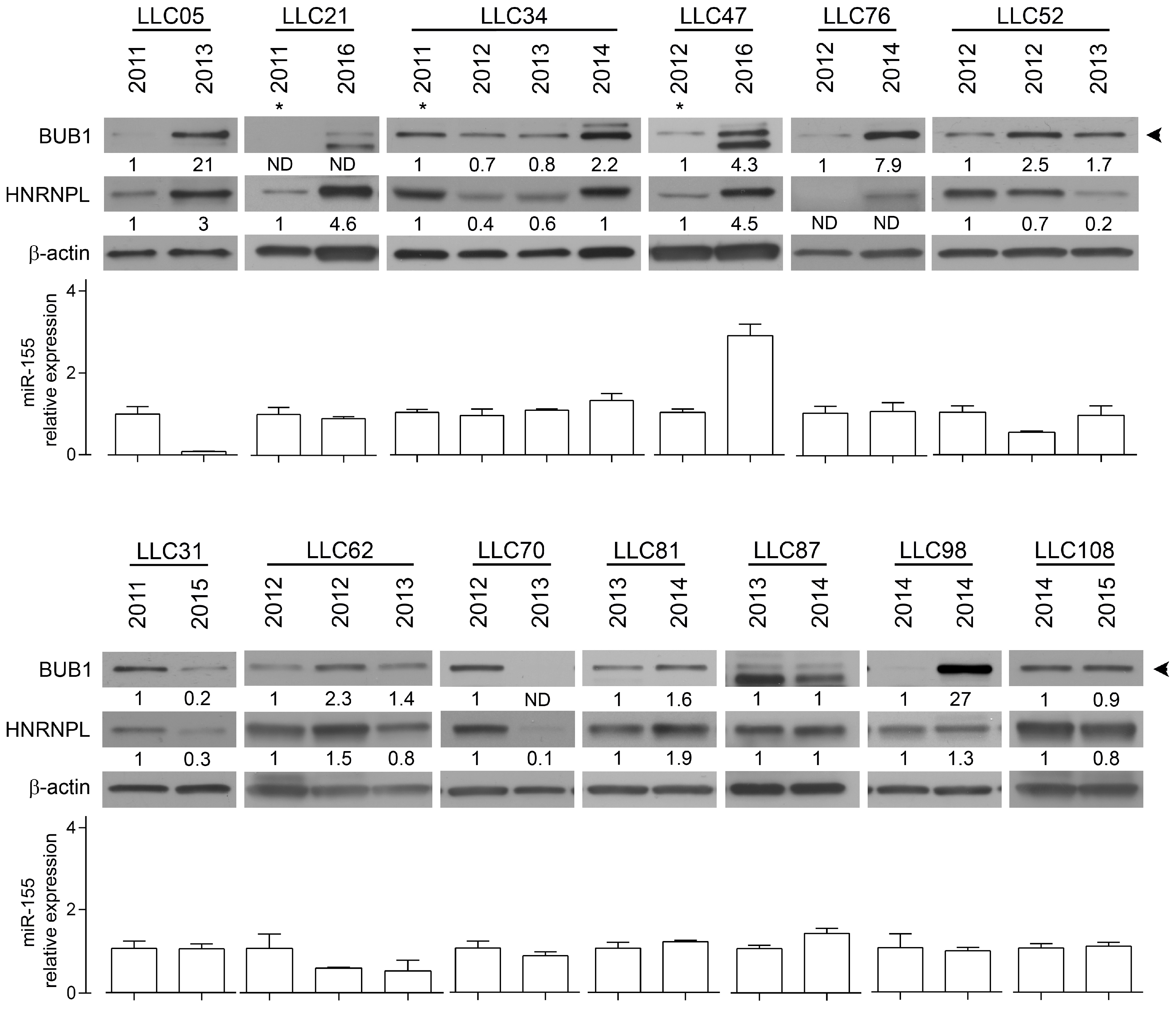

2.2. The RNA-Binding Protein HNRNPL Correlates Positively with BUB1 in CLL Cells

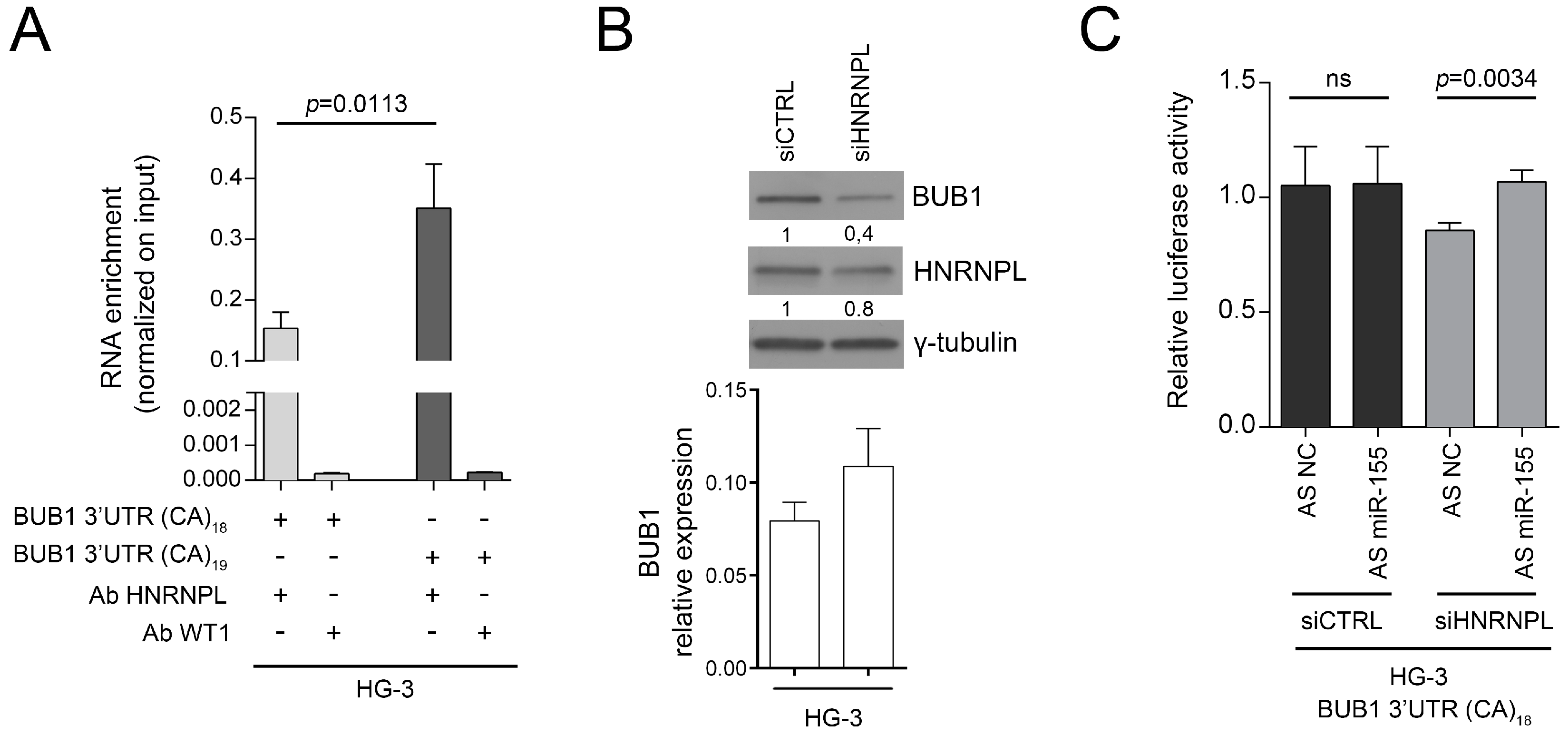

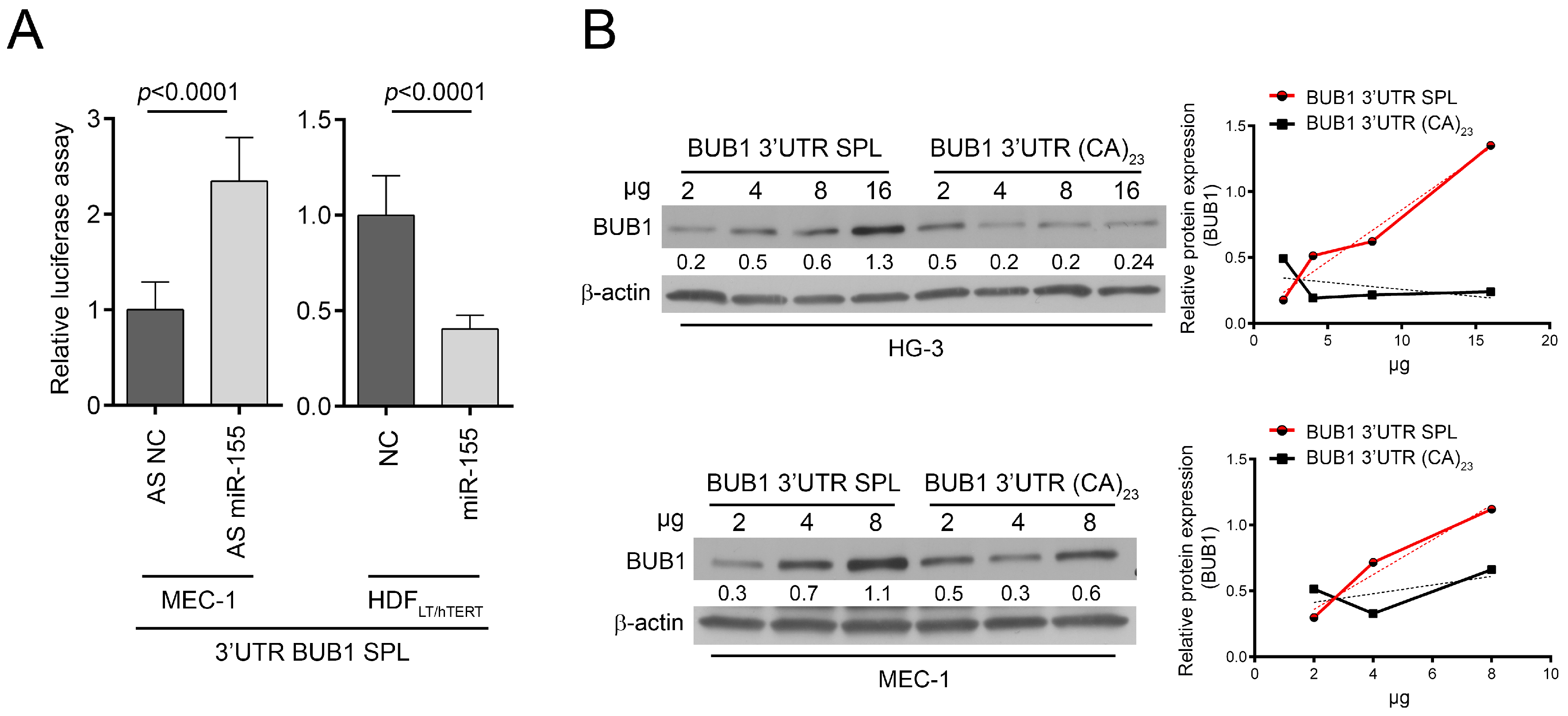

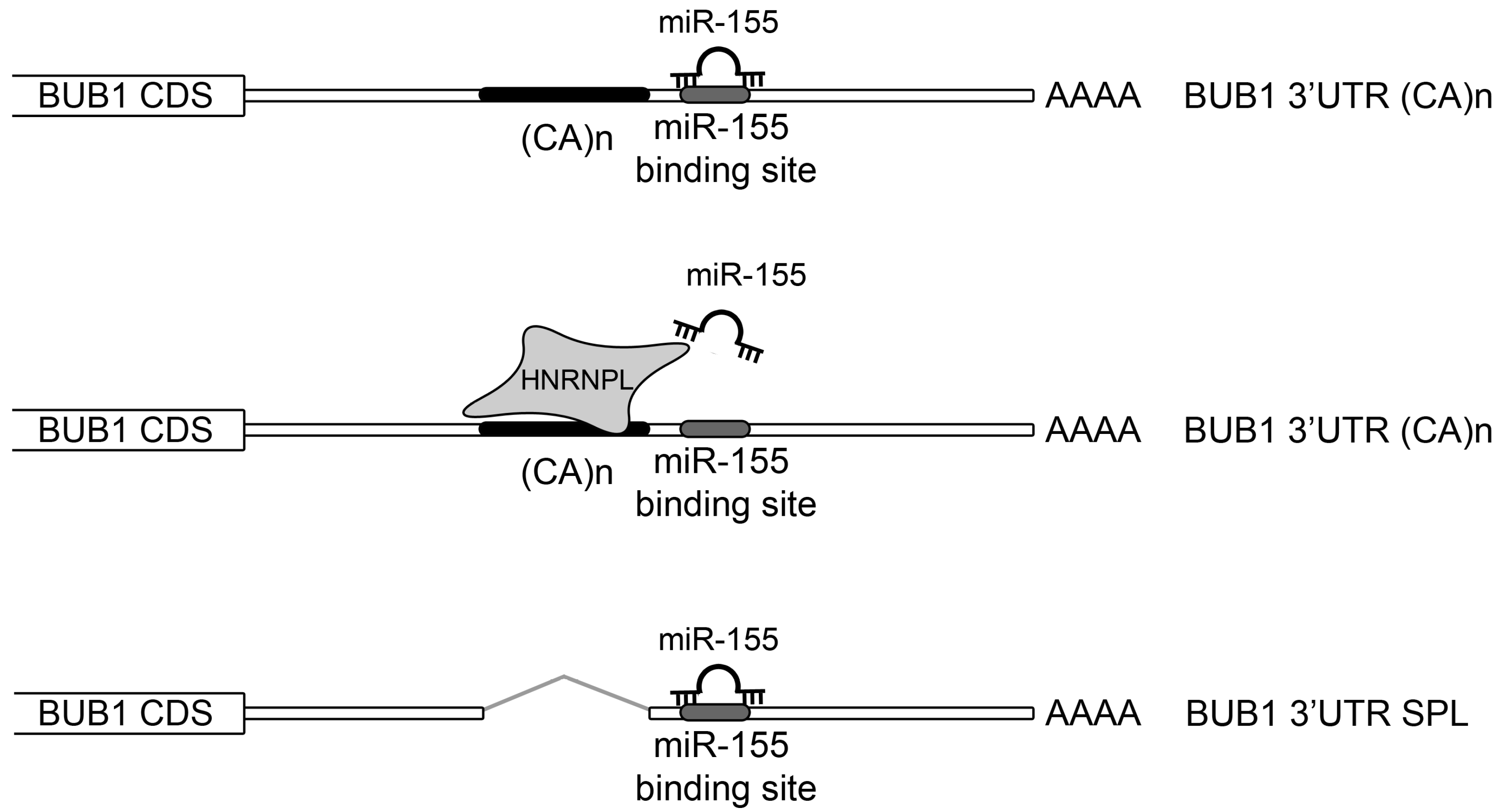

2.3. HNRNPL Interaction on 3′UTR of BUB1 Inhibits miR-155 Targeting

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Primary Cells

4.2. DNA/RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Plasmids

4.5. Cells Transfection and Luciferase Target Assays

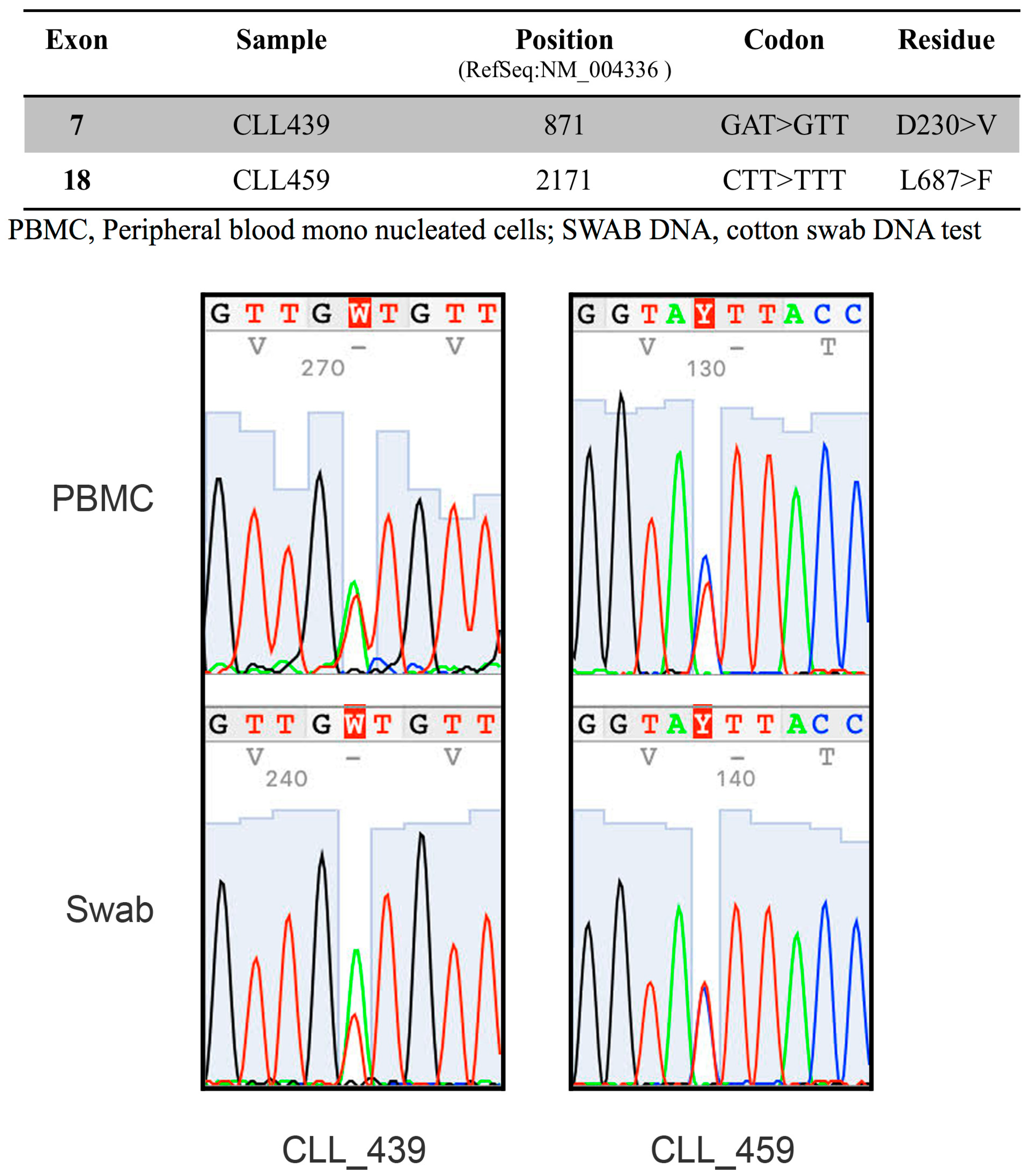

4.6. Mutational Analysis

4.7. Western Blotting

4.8. Karyotype Analyses

4.9. Immunofluorescence

4.10. RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

4.11. DNA Fragment Length Analysis (FLA)

4.12. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| miR-155 | Hsa-miR-155-5p |

| BUB1 | mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine kinase budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 |

| CENP-F | centromere protein F |

| ZW10 | zw10 kinetochore protein |

| HNRNPL | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L |

| CLL | chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| SAC | spindle assembly checkpoint |

| CIN | chromosome instability |

| HDF | human normal dermal fibroblast |

| HD | healthy donors |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| HDFLT/hTERT | Immortalized HDF cells |

| FLA | fragment length analysis |

| MLH1 | mutL homolog 1 |

| MSH6 | mutS homolog 6 |

| MSI | microsatellite instability |

| MBL | monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis |

| RIP | RNA immunoprecipitation |

References

- Valeri, N.; Gasparini, P.; Fabbri, M.; Braconi, C.; Veronese, A.; Lovat, F.; Adair, B.; Vannini, I.; Fanini, F.; Bottoni, A.; et al. Modulation of mismatch repair and genomic stability by miR-155. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6982–6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinami, R.; Ercolani, C.; Petti, E.; Piazza, S.; Ciani, Y.; Sestito, R.; Sacconi, A.; Biagioni, F.; le Sage, C.; Agami, R.; et al. miR-155 Drives Telomere Fragility in Human Breast Cancer by Targeting TRF1. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 4145–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, P.; Lovat, F.; Fassan, M.; Casadei, L.; Cascione, L.; Jacob, N.K.; Carasi, S.; Palmieri, D.; Costinean, S.; Shapiro, C.L.; et al. Protective role of miR-155 in breast cancer through RAD51 targeting impairs homologous recombination after irradiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4536–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauth, C.; O’Hare, M.J.; Lederer, G.; Jat, P.S.; Speicher, M.R. Order of genetic events is critical determinant of aberrations in chromosome count and structure. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2004, 40, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, M.J.; Bond, J.; Clarke, C.; Takeuchi, Y.; Atherton, A.J.; Berry, C.; Moody, J.; Silver, A.R.J.; Davies, D.C.; Alsop, A.E.; et al. Conditional immortalization of freshly isolated human mammary fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagotto, S.; Veronese, A.; Soranno, A.; Lanuti, P.; Marco, M.D.; Russo, M.V.; Ramassone, A.; Marchisio, M.; Simeone, P.; Franchi, P.E.G.; et al. Hsa-miR-155-5p drives aneuploidy at early stages of cellular transformation. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 13036–13047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.V.; Vergnolle, M.A.; Hussein, D.; Wozniak, M.J.; Allan, V.J.; Taylor, S.S. Silencing Cenp-F weakens centromeric cohesion, prevents chromosome alignment and activates the spindle checkpoint. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 4889–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.H.; Ai, J.S.; Liang, C.G.; Hou, Y.; Chen, D.Y.; Schatten, H.; Sun, Q.Y. Bub1 prevents chromosome misalignment and precocious anaphase during mouse oocyte meiosis. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, K.; Malureanu, L.; Baker, D.J.; Abraham, S.C.; van Deursen, J.M. Bub1 mediates cell death in response to chromosome missegregation and acts to suppress spontaneous tumorigenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 179, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Jin, F.; Jeganathan, K.B.; van Deursen, J.M. Whole chromosome instability caused by Bub1 insufficiency drives tumorigenesis through tumor suppressor gene loss of heterozygosity. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musio, A.; Montagna, C.; Zambroni, D.; Indino, E.; Barbieri, O.; Citti, L.; Villa, A.; Ried, T.; Vezzoni, P. Inhibition of BUB1 results in genomic instability and anchorage-independent growth of normal human fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 2855–2863. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, H.; Lengauer, C. Aneuploidy and cancer. Nature 2004, 432, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, B.A.A.; Silk, A.D.; Montagna, C.; Verdier-Pinard, P.; Cleveland, D.W. Aneuploidy acts both oncogenically and as a tumor suppressor. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, P.C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science 1976, 194, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.F.; Furge, K.; Koeman, J.; Dykema, K.; Su, Y.L.; Cutler, M.L.; Werts, A.; Haak, P.; Woude, G.F.V. Chromosome instability, chromosome transcriptome, and clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8995–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Davis, A.; McDonald, T.O.; Sei, E.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Tsai, P.C.; Casasent, A.; Waters, J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Punctuated copy number evolution and clonal stasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowetz, F. A saltationist theory of cancer evolution. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1102–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarifar, F.; Yao, P.; Eswarappa, S.M.; Fox, P.L. Repression of VEGFA by CA-rich element-binding microRNAs is modulated by hnRNP L. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossbach, O.; Hung, L.H.; Khrameeva, E.; Schreiner, S.; Konig, J.; Curk, T.; Zupan, B.; Ule, J.; Gelfand, M.S.; Bindereif, A. Crosslinking-immunoprecipitation (iCLIP) analysis reveals global regulatory roles of hnRNP L. RNA Biol. 2014, 11, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bernardo, M.C.; Crowther-Swanepoel, D.; Broderick, P.; Webb, E.; Sellick, G.; Wild, R.; Sullivan, K.; Vijayakrishnan, J.; Wang, Y.; Pittman, A.M.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies six susceptibility loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankarling, G.; Cole, B.S.; Mallory, M.J.; Lynch, K.W. Transcriptome-wide RNA interaction profiling reveals physical and functional targets of hnRNP L in human T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, J.; Stangl, K.; Lane, W.S.; Bindereif, A. HnRNP L stimulates splicing of the eNOS gene by binding to variable-length CA repeats. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2003, 10, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimini, D. Merotelic kinetochore orientation, aneuploidy, and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1786, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.L.; Cibulskis, K.; Helman, E.; McKenna, A.; Shen, H.; Zack, T.; Laird, P.W.; Onofrio, R.C.; Winckler, W.; Weir, B.A.; et al. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhoum, S.F.; Ngo, B.; Laughney, A.M.; Cavallo, J.A.; Murphy, C.J.; Ly, P.; Shah, P.; Sriram, R.K.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Taunk, N.K.; et al. Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response. Nature 2018, 553, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhoum, S.F.; Cantley, L.C. The Multifaceted Role of Chromosomal Instability in Cancer and Its Microenvironment. Cell 2018, 174, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.L.; Bakhoum, S.F.; Compton, D.A. Mechanisms of chromosomal instability. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R285–R295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkbak, N.J.; Eklund, A.C.; Li, Q.; McClelland, S.E.; Endesfelder, D.; Tan, P.; Tan, I.B.; Richardson, A.L.; Szallasi, Z.; Swanton, C. Paradoxical relationship between chromosomal instability and survival outcome in cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3447–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkard, M.E.; Weaver, B.A. Tuning Chromosomal Instability to Optimize Tumor Fitness. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansregret, L.; Patterson, J.O.; Dewhurst, S.; Lopez-Garcia, C.; Koch, A.; McGranahan, N.; Chao, W.C.H.; Barry, D.J.; Rowan, A.; Instrell, R.; et al. APC/C Dysfunction Limits Excessive Cancer Chromosomal Instability. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Mraz, M.; Fecteau, J.F.; Yu, J.; Ghia, E.M.; Zhang, L.; Bao, L.; Rassenti, L.Z.; et al. MicroRNA-155 influences B-cell receptor signaling and associates with aggressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2014, 124, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.A.; van Heesbeen, R.; Blomen, V.A.; Janssen, L.M.E.; van Diemen, F.; Brummelkamp, T.R.; Medema, R.H. BUB1 Is Essential for the Viability of Human Cells in which the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Is Compromised. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 1424–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tighe, A.; Johnson, V.L.; Albertella, M.; Taylor, S.S. Aneuploid colon cancer cells have a robust spindle checkpoint. EMBO Rep. 2001, 2, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemeister, G.; Mengel, A.; Fernandez-Montalvan, A.E.; Bone, W.; Schroder, J.; Zitzmann-Kolbe, S.; Briem, H.; Prechtl, S.; Holton, S.J.; Monning, U.; et al. Inhibition of BUB1 Kinase by BAY 1816032 Sensitizes Tumor Cells toward Taxanes, ATR, and PARP Inhibitors In Vitro and In Vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Hajkova, P.; Barton, S.C.; Lao, K.; Surani, M.A. MicroRNA expression profiling of single whole embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; McMichael, J.; Dang, H.X.; Maher, C.A.; Ding, L.; Ley, T.J.; Mardis, E.R.; Wilson, R.K. Visualizing tumor evolution with the fishplot package for R. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurowska-Stolarska, M.; Alivernini, S.; Ballantine, L.E.; Asquith, D.L.; Millar, N.L.; Gilchrist, D.S.; Reilly, J.; Ierna, M.; Fraser, A.R.; Stolarski, B.; et al. MicroRNA-155 as a proinflammatory regulator in clinical and experimental arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11193–11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, R.M.; Taganov, K.D.; Boldin, M.P.; Cheng, G.; Baltimore, D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chao, T.C.; Chang, K.Y.; Lin, N.; Patil, V.S.; Shimizu, C.; Head, S.R.; Burns, J.C.; Rana, T.M. The long noncoding RNA THRIL regulates TNFalpha expression through its interaction with hnRNPL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderberg, M.; Raffalli-Mathieu, F.; Lang, M.A. Inflammation modulates the interaction of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) I/polypyrimidine tract binding protein and hnRNP L with the 3′untranslated region of the murine inducible nitric-oxide synthase mRNA. Mol. Pharm. 2002, 62, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNairn, A.J.; Chuang, C.H.; Bloom, J.C.; Wallace, M.D.; Schimenti, J.C. Female-biased embryonic death from inflammation induced by genomic instability. Nature 2019, 567, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagotto, S.; Veronese, A.; Soranno, A.; Balatti, V.; Ramassone, A.; Guanciali-Franchi, P.E.; Palka, G.; Innocenti, I.; Autore, F.; Rassenti, L.Z.; et al. HNRNPL Restrains miR-155 Targeting of BUB1 to Stabilize Aberrant Karyotypes of Transformed Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancers 2019, 11, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11040575

Pagotto S, Veronese A, Soranno A, Balatti V, Ramassone A, Guanciali-Franchi PE, Palka G, Innocenti I, Autore F, Rassenti LZ, et al. HNRNPL Restrains miR-155 Targeting of BUB1 to Stabilize Aberrant Karyotypes of Transformed Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancers. 2019; 11(4):575. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11040575

Chicago/Turabian StylePagotto, Sara, Angelo Veronese, Alessandra Soranno, Veronica Balatti, Alice Ramassone, Paolo E. Guanciali-Franchi, Giandomenico Palka, Idanna Innocenti, Francesco Autore, Laura Z. Rassenti, and et al. 2019. "HNRNPL Restrains miR-155 Targeting of BUB1 to Stabilize Aberrant Karyotypes of Transformed Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia" Cancers 11, no. 4: 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11040575

APA StylePagotto, S., Veronese, A., Soranno, A., Balatti, V., Ramassone, A., Guanciali-Franchi, P. E., Palka, G., Innocenti, I., Autore, F., Rassenti, L. Z., Kipps, T. J., Mariani-Costantini, R., Laurenti, L., Croce, C. M., & Visone, R. (2019). HNRNPL Restrains miR-155 Targeting of BUB1 to Stabilize Aberrant Karyotypes of Transformed Cells in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancers, 11(4), 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11040575