Profiling of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Circulating Tumour Cells—Are We Ready for the ‘Liquid’ Revolution?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Multifactorial Prognostic and Predictive Panels in Invasive Breast Cancer

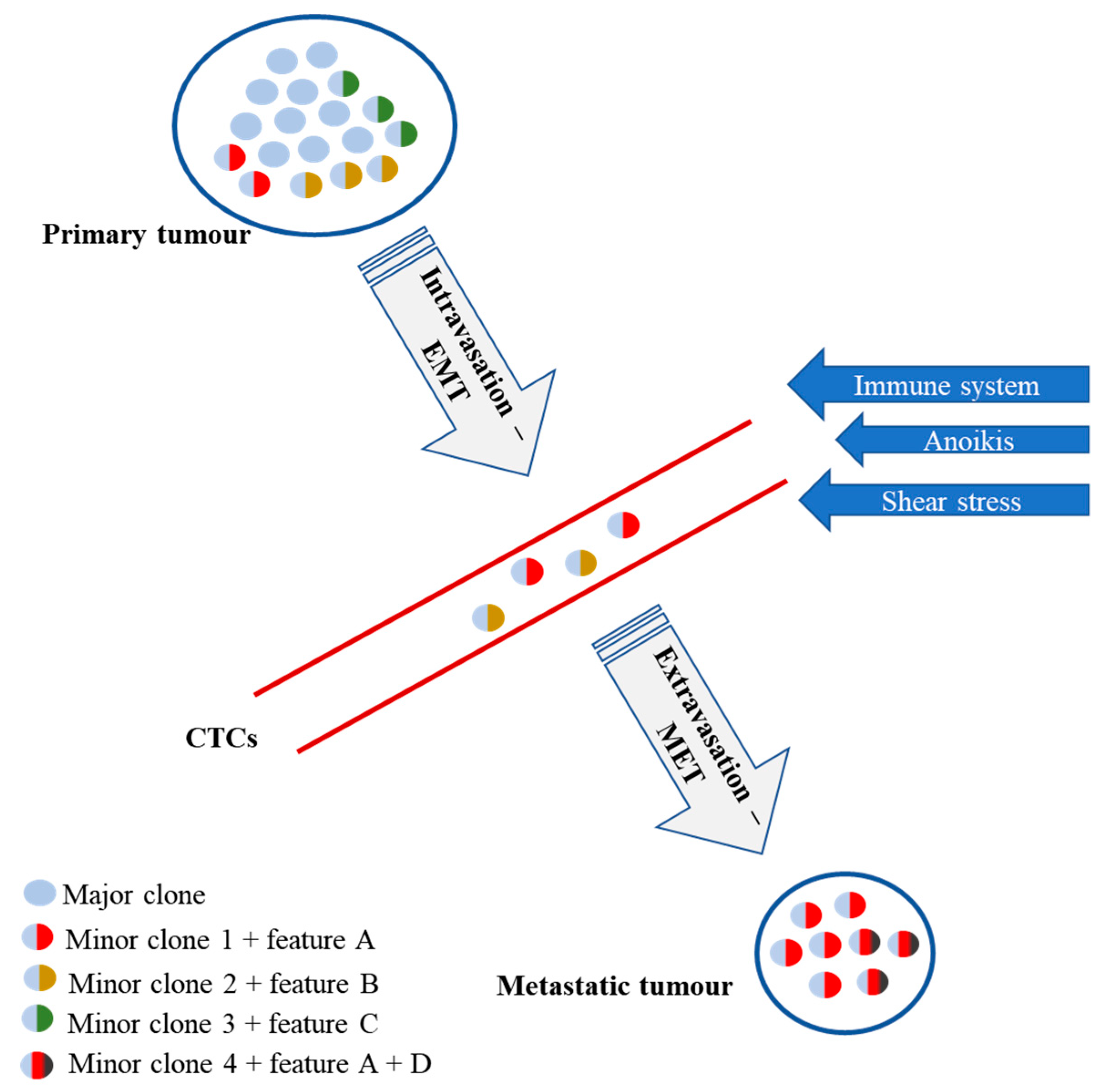

3. Inter- and Intratumoural Heterogeneity of IBC

4. CTCs—Clinical Potential and Limitations

5. Methods of CTCs isolation

6. The Prognostic and Predictive Value of CTCs Detection and Quantification in Patients with IBC

7. Assessment of Multiparametric Panels in IBC CTCs

7.1. Protein Level

7.2. DNA Level

7.3. RNA Level

7.4. microRNA Level

8. Single Cell Analysis of CTCs—Future or Confusion?

9. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram I, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman D, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinn, H.-P.; Kreipe, H. A brief overview of the WHO classification of breast tumors, 4th edition, focusing on issues and updates from the 3rd edition. Breast care 2013, 8, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, J.C.; Barlock, A.; Huff, K.K.; Lippman, M.E. Changes in multiple or sequential estrogen receptor determinations in breast cancer. Cancer 1980, 45, 792–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, L.S.; Karlsson, E.; Wilking, U.M.; Johansson, U.; Hartman, J.; Lidbrink, E.K.; Hatschek, T.; Skoog, L.; Bergh, J. Clinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2601–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M.; Fackler, M.J.; Halushka, M.K.; Molavi, D.W.; Taylor, M.E.; Teo, W.W.; Griffin, C.; Fetting, J.; Davidson, N.E.; De Marzo, A.M.; et al. Heterogeneity of breast cancer metastases: comparison of therapeutic target expression and promoter methylation between primary tumors and their multifocal metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1938–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 3786–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turashvili, G.; Brogi, E. Tumor heterogeneity in breast cancer. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.A.; Guttery, D.S.; Hills, A.; Fernandez-Garcia, D.; Page, K.; Rosales, B.M.; Goddard, K.S.; Hastings, R.K.; Luo, J.; Ogle, O.; et al. Personalized medicine and imaging mutation analysis of cell-free DNA and single circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients with high circulating tumor cell counts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Mu, Z.; Rademaker, A.W.; Austin, L.K.; Strickland, K.S.; Costa, R.L.B.; Nagy, R.J.; Zagonel, V.; Taxter, T.J.; Behdad, A.; et al. Cell-free DNA and circulating tumor cells: comprehensive liquid biopsy analysis in advanced breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Bardia, A.; Wittner, B.S.; Stott, S.L.; Smas, M.E.; Ting, D.T.; Isakoff, S.J.; Ciciliano, J.C.; Wells, M.N.; Shah, A.M.; et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science (80-) 2013, 339, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttery, D.S.; Page, K.; Hills, A.; Woodley, L.; Marchese, S.D.; Rghebi, B.; Hastings, R.K.; Luo, J.; Pringle, J.H.; Stebbing, J.; et al. Noninvasive detection of activating estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) mutations in estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Chem. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.-C.; Peeters, D.J.; Fehm, T.; Nolé, F.; Gisbert-Criado, R.; Mavroudis, D.; Grisanti, S.; Generali, D.; Garcia-Saenz, J.A.; Stebbing, J.; et al. Clinical validity of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. Oncol. 2014, 15, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.-J.; Tsui, D.W.Y.; Murtaza, M.; Biggs, H.; Rueda, O.M.; Chin, S.-F.; Dunning, M.J.; Gale, D.; Forshew, T.; Mahler-Araujo, B.; et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, M.A.; Stoupis, G.; Theodoropoulos, P.A.; Mavroudis, D.; Georgoulias, V.; Agelaki, S. Circulating tumor cells with stemness and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition features are chemoresistant and predictive of poor outcome in metastatic breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, molcanther.0584.2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markiewicz, A.; Nagel, A.; Szade, J.; Majewska, H.; Skokowski, J.; Seroczynska, B.; Stokowy, T.; Welnicka-Jaskiewicz, M.; Zaczek, A.J. Aggressive phenotype of cells disseminated via hematogenous and lymphatic route in breast cancer patients. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, J.A.; Page, K.; Blighe, K.; Hava, N.; Guttery, D.; Ward, B.; Brown, J.; Ruangpratheep, C.; Stebbing, J.; Payne, R.; et al. Genomic analysis of circulating cell-free DNA infers breast cancer dormancy. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, M.H.D.; Bender, S.; Krahn, T.; Schlange, T. ctDNA and CTCs in liquid biopsy - current status and where we need to progress. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolacinska, A.; Morawiec, J.; Fendler, W.; Malachowska, B.; Morawiec, Z.; Szemraj, J.; Pawlowska, Z.; Chowdhury, D.; Choi, Y.E.; Kubiak, R.; et al. Association of microRNAs and pathologic response to preoperative chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer: Preliminary report. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 2851–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka, D.; Braun, M.; Kordek, R.; Sadej, R.; Romanska, H. MicroRNAs in regulation of triple-negative breast cancer progression. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 144, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Gregory, R.I. MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurozumi, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kurosumi, M.; Ohira, M.; Matsumoto, H.; Horiguchi, J. Recent trends in microRNA research into breast cancer with particular focus on the associations between microRNAs and intrinsic subtypes. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 62, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senkus, E.; Kyriakides, S.; Ohno, S.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Poortmans, P.; Rutgers, E.; Zackrisson, S. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up † incidence and epidemiology. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, v8–v30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godet, I.; Gilkes, D.M. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integr. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, O.L.; Spies, N.C.; Anurag, M.; Griffith, M.; Luo, J.; Tu, D.; Yeo, B.; Kunisaki, J.; Miller, C.A.; Krysiak, K.; et al. The prognostic effects of somatic mutations in ER-positive breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørlie, T.; Perou, C.M.; Tibshirani, R.; Aas, T.; Geisler, S.; Johnsen, H.; Hastie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10869–10874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørlie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Parker, J.; Hastie, T.; Marron, J.S.; Nobel, A.; Deng, S.; Johnsen, H.; Pesich, R.; Geisler, S.; et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8418–8423. [Google Scholar]

- Perou, C.M.; Sørlie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; van de Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Rees, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.S.; Mullins, M.; Cheung, M.C.U.; Leung, S.; Voduc, D.; Vickery, T.; Davies, S.; Fauron, C.; He, X.; Hu, Z.; et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, A.; Perou, C.M. Deconstructing the molecular portraits of breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittaneh, M.; Montero, A.J.; Glück, S. Molecular profiling for breast cancer: A comprehensive review. Biomark. Cancer 2013, 5, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallden, B.; Storhoff, J.; Nielsen, T.; Dowidar, N.; Schaper, C.; Ferree, S.; Liu, S.; Leung, S.; Geiss, G.; Snider, J.; et al. Development and verification of the PAM50-based Prosigna breast cancer gene signature assay. BMC Med. Genomics 2015, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowsett, M.; Sestak, I.; Lopez-Knowles, E.; Sidhu, K.; Dunbier, A.K.; Cowens, J.W.; Ferree, S.; Storhoff, J.; Schaper, C.; Cuzick, J. Comparison of PAM50 risk of recurrence score with oncotype DX and IHC4 for predicting risk of distant recurrence after endocrine therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2783–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prat, A.; Parker, J.S.; Fan, C.; Perou, C.M. PAM50 assay and the three-gene model for identifying the major and clinically relevant molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 135, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, N.P.; Lundberg, A.; Lindström, L.S.; Harrell, J.C.; Foukakis, T.; Carlsson, L.; Einbeigi, Z.; Linderholm, B.K.; Loman, N.; Malmberg, M.; et al. PAM50 provides prognostic information when applied to the lymph node metastases of advanced breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 7225–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Li, T.; Bai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhan, J.; Shi, B. Breast cancer intrinsic subtype classification, clinical use and future trends. Am J Cancer Res 2015, 5, 2929–2943. [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver, M.J.; He, Y.D.; van’t Veer, L.J.; Dai, H.; Hart, A.A.M.; Voskuil, D.W.; Schreiber, G.J.; Peterse, J.L.; Roberts, C.; Marton, M.J.; et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1999–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van’t Veer, L.J.; Dai, H.; van de Vijver, M.J.; He, Y.D.; Hart, A.A.M.; Mao, M.; Peterse, H.L.; van der Kooy, K.; Marton, M.J.; Witteveen, A.T.; et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature 2002, 415, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; van’t Veer, L.J.; Bogaerts, J.; Slaets, L.; Viale, G.; Delaloge, S.; Pierga, J.-Y.; Brain, E.; Causeret, S.; DeLorenzi, M.; et al. 70-Gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early-stage breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.; Shak, S.; Tang, G.; Kim, C.; Baker, J.; Cronin, M.; Baehner, F.L.; Walker, M.G.; Watson, D.; Park, T.; et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2817–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.O.; Parker, J.S.; Leung, S.; Voduc, D.; Ebbert, M.; Vickery, T.; Davies, S.R.; Snider, J.; Stijleman, I.J.; Reed, J.; et al. A comparison of PAM50 intrinsic subtyping with immunohistochemistry and clinical prognostic factors in tamoxifen-treated estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5222–5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerevall, P.-L.; Ma, X.-J.; Li, H.; Salunga, R.; Kesty, N.C.; Erlander, M.G.; Sgroi, D.C.; Holmlund, B.; Skoog, L.; Fornander, T.; et al. Prognostic utility of HOXB13:IL17BR and molecular grade index in early-stage breast cancer patients from the Stockholm trial. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morigi, C. Highlights from the 15th St Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference 15-18 March, 2017, Vienna: Tailored treatments for patients with early breast cancer. ecancermedicalscience 2017, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipits, M.; Rudas, M.; Jakesz, R.; Dubsky, P.; Fitzal, F.; Singer, C.F.; Dietze, O.; Greil, R.; Jelen, A.; Sevelda, P.; et al. A new molecular predictor of distant recurrence in er-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer adds independent information to conventional clinical risk factors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6012–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimbung, S.; Loman, N.; Hedenfalk, I. Clinical and molecular complexity of breast cancer metastases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffer, C.L.; Weinberg, R.A. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 2011, 331, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler, I.J. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: The “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosse, S.A.; Gorges, T.M.; Pantel, K. Biology, detection, and clinical implications of circulating tumor cells. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurilio, G.; Disalvatore, D.; Pruneri, G.; Bagnardi, V.; Viale, G.; Curigliano, G.; Adamoli, L.; Munzone, E.; Sciandivasci, A.; De Vita, F.; et al. A meta-analysis of oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 discordance between primary breast cancer and metastases. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krøigård, A.B.; Larsen, M.J.; Thomassen, M.; Kruse, T.A. Molecular concordance between primary breast cancer and matched metastases. Breast J. 2016, 22, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Naume, B. Circulating and disseminated tumor cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 1623–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, N.V.; Bardia, A.; Wittner, B.S.; Benes, C.; Ligorio, M.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, M.; Sundaresan, T.K.; Licausi, J.A.; Desai, R.; et al. HER2 expression identifies dynamic functional states within circulating breast cancer cells. Nature 2016, 537, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, T. A case of cancer in which cells similar to those in the rumours were seen in the blood after death. Aust. Med. J. 1869, 14, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Allard, W.J.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Repollet, M.; Connelly, M.C.; Rao, C.; Tibbe, A.G.J.; Uhr, J.W.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6897–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Z.; Wang, C.; Ye, Z.; Austin, L.; Civan, J.; Hyslop, T.; Palazzo, J.P.; Jaslow, R.; Li, B.; Myers, R.E.; et al. Prospective assessment of the prognostic value of circulating tumor cells and their clusters in patients with advanced-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 154, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, N.; Bardia, A.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Donaldson, M.C.; Wittner, B.S.; Spencer, J.A.; Yu, M.; Pely, A.; Engstrom, A.; Zhu, H.; et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell 2014, 158, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.H.; Wendel, M.; Luttgen, M.; Yoshioka, C.; Marrinucci, D.; Lazar, D.; Schram, E.; Nieva, J.; Bazhenova, L.; Morgan, A.; et al. Characterization of circulating tumor cell aggregates identified in patients with epithelial tumors. Phys. Biol. 2012, 9, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.; Tripathy, D.; Frenkel, E.P.; Shete, S.; Naftalis, E.Z.; Huth, J.F.; Beitsch, P.D.; Leitch, M.; Hoover, S.; Euhus, D.; et al. Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer dormancy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 8152–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbanua, M.J.M.; Park, J.W. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-55947-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.M.; Ramani, V.C.; Jeffrey, S.S. Circulating tumor cell technologies. Mol. Oncol. 2016, 10, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, A.; Ksia̧zkiewicz, M.; Wełnicka-Jaśkiewicz, M.; Seroczyńska, B.; Skokowski, J.; Szade, J.; Zaczek, A.J. Mesenchymal phenotype of CTC-enriched blood fraction and lymph node metastasis formation potential. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieuwerts, A.M.; Kraan, J.; Bolt-de Vries, J.; van der Spoel, P.; Mostert, B.; Martens, J.W.M.; Gratama, J.-W.; Sleijfer, S.; Foekens, J.A. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in large quantities of contaminating leukocytes by a multiplex real-time PCR. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 118, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mego, M.; Cierna, Z.; Janega, P.; Karaba, M.; Minarik, G.; Benca, J.; Sedlácková, T.; Sieberova, G.; Gronesova, P.; Manasova, D.; et al. Relationship between circulating tumor cells and epithelial to mesenchymal transition in early breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Reuben, J.M.; Doyle, G.V.; Allard, W.J.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulou, E.; Yang, L.-Y.; Rangel, K.M.; Reuben, J.M.; Hsu, L.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Valero, V.; Fritsche, H.A.; Cristofanilli, M. Comparison of assay methods for detection of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: AdnaGen AdnaTest BreastCancer Select/DetectTM versus Veridex CellSearchTM system. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluim, D.; Devriese, L.A.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.M. Validation of a multiparameter flow cytometry method for the determination of phosphorylated extracellular-signal-regulated kinase and DNA in circulating tumor cells. Cytom. Part A 2012, 81A, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talasaz, A.H.; Powell, A.A.; Huber, D.E.; Berbee, J.G.; Roh, K.-H.; Yu, W.; Xiao, W.; Davis, M.M.; Pease, R.F.; Mindrinos, M.N.; et al. Isolating highly enriched populations of circulating epithelial cells and other rare cells from blood using a magnetic sweeper device. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3970–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorges, T.M.; Tinhofer, I.; Drosch, M.; Röse, L.; Zollner, T.M.; Krahn, T.; von Ahsen, O. Circulating tumour cells escape from EpCAM-based detection due to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fusi, A.; Klopocki, E.; Schmittel, A.; Tinhofer, I.; Nonnenmacher, A.; Keilholz, U. Negative enrichment by immunomagnetic nanobeads for unbiased characterization of circulating tumor cells from peripheral blood of cancer patients. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapin, M.; Tjensvoll, K.; Oltedal, S.; Buhl, T.; Gilje, B.; Smaaland, R.; Nordgård, O. MINDEC-An enhanced negative depletion strategy for circulating tumour cell enrichment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillig, T.; Horn, P.; Nygaard, A.-B.; Haugaard, A.S.; Nejlund, S.; Brandslund, I.; Sölétormos, G. In vitro detection of circulating tumor cells compared by the CytoTrack and CellSearch methods. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 4597–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somlo, G.; Lau, S.K.; Frankel, P.; Hsieh, H.B.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Krivacic, R.; Bruce, R.H. Multiple biomarker expression on circulating tumor cells in comparison to tumor tissues from primary and metastatic sites in patients with locally advanced/inflammatory, and stage IV breast cancer, using a novel detection technology. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 128, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrinucci, D.; Bethel, K.; Kolatkar, A.; Luttgen, M.S.; Malchiodi, M.; Baehring, F.; Voigt, K.; Lazar, D.; Nieva, J.; Bazhenova, L.; et al. Fluid biopsy in patients with metastatic prostate, pancreatic and breast cancers. Phys. Biol. 2012, 9, 016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenic, R.; Treue, D.; Lehmann, A.; Hummel, M.; Dietel, M.; Denkert, C.; Budczies, J. Comparison of targeted next-generation sequencing and Sanger sequencing for the detection of PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2015, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasik, S.; Schuster, C.; Ortlepp, C.; Platzbecker, U.; Bornhäuser, M.; Schetelig, J.; Ehninger, G.; Folprecht, G.; Thiede, C. An optimized targeted Next-Generation Sequencing approach for sensitive detection of single nucleotide variants. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2018, 15, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, T.T.; Bardia, A.; Spring, L.M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Kalinich, M.; Dubash, T.; Sundaresan, T.; Hong, X.; LiCausi, J.A.; Ho, U.; et al. A digital RNA signature of circulating tumor cells predicting early therapeutic response in localized and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1286–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, K.; Cote, R.J.; Fodstad, O. Detection and clinical importance of micrometastatic disease. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjanappa, M.; Hao, Y.; Simpson, E.R.; Bhat-Nakshatri, P.; Nelson, J.B.; Tersey, S.A.; Mirmira, R.G.; Cohen-Gadol, A.A.; Saadatzadeh, M.R.; Li, L.; et al. A system for detecting high impact-low frequency mutations in primary tumors and metastases. Oncogene 2018, 37, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.-T.; Cui, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.-F.; Cui, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, J. Circulating tumor cell status monitors the treatment responses in breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riethdorf, S.; Müller, V.; Loibl, S.; Nekljudova, V.; Weber, K.; Huober, J.; Fehm, T.; Schrader, I.; Hilfrich, J.; Holms, F.; et al. Prognostic impact of circulating tumor cells for breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant “geparquattro” trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5384–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.-C.; Michiels, S.; Riethdorf, S.; Mueller, V.; Esserman, L.J.; Lucci, A.; Naume, B.; Horiguchi, J.; Gisbert-Criado, R.; Sleijfer, S.; et al. Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A meta-analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucci, A.; Hall, C.S.; Lodhi, A.K.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Anderson, A.E.; Xiao, L.; Bedrosian, I.; Kuerer, H.M.; Krishnamurthy, S. Circulating tumour cells in non-metastatic breast cancer: A prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiadis, M.; Xenidis, N.; Perraki, M.; Apostolaki, S.; Politaki, E.; Kafousi, M.; Stathopoulos, E.N.; Stathopoulou, A.; Lianidou, E.; Chlouverakis, G.; et al. Different prognostic value of cytokeratin-19 mRNA–positive circulating tumor cells according to estrogen receptor and HER2 status in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 5194–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, T.J.; Bosma, A.J.; Baumbusch, L.O.; Synnestvedt, M.; Borgen, E.; Russnes, H.G.; Schlichting, E.; van’t Veer, L.J.; Naume, B. The prognostic significance of tumour cell detection in the peripheral blood versus the bone marrow in 733 early-stage breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rack, B.; Schindlbeck, C.; Jückstock, J.; Andergassen, U.; Hepp, P.; Zwingers, T.; Friedl, T.W.P.; Lorenz, R.; Tesch, H.; Fasching, P.A.; et al. Circulating tumor cells predict survival in early average-to-high risk breast cancer patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Gong, L.; Zhang, T.; Ye, J.; Chai, L.; Ni, C.; Mao, Y. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 18, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C.; Shields, P.G.; Warren, R.D.; Cohen, P.; Wilkinson, M.; Ottaviano, Y.L.; Rao, S.B.; Eng-wong, J.; Seillier-moiseiwitsch, F.; Noone, A.; et al. Circulating tumor cells: A useful predictor of treatment efficacy in metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5153–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ling, F.; Gui, A.; Chen, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z. Predictive value of circulating tumor cells for evaluating short- and long-term efficacy of chemotherapy for breast cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 4808–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerage, J.B.; Barlow, W.E.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Winer, E.P.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Srkalovic, G.; Tejwani, S.; Schott, A.F.; O’Rourke, M.A.; Lew, D.L.; et al. Circulating tumor cells and response to chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: SWOG S0500. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3483–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinsky, K.; Mayer, J.A.; Xu, X.; Pham, T.; Wong, K.L.; Villarin, E.; Pircher, T.J.; Brown, M.; Maurer, M.A.; Bischoff, F.Z. Correlation of hormone receptor status between circulating tumor cells, primary tumor, and metastasis in breast cancer patients. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2015, 17, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, B.; Müller, V.; Tewes, M.; Zeitz, J.; Kasimir-Bauer, S.; Loehberg, C.R.; Rack, B.; Schneeweiss, A.; Fehm, T. Comparison of estrogen and progesterone receptor status of circulating tumor cells and the primary tumor in metastatic breast cancer patients. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 122, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayan, A.; Hannemann, J.; Spötter, J.; Müller, V.; Pantel, K.; Joosse, S.A. Heterogeneity of estrogen receptor expression in circulating tumor cells from metastatic breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.; Rack, B.; Kuhn, C.; Hofmann, S.; Finkenzeller, C.; Jäger, B.; Jeschke, U.; Doisneau-Sixou, S.F. Heterogeneity of ERα and ErbB2 status in cell lines and circulating tumor cells of metastatic breast cancer patients. Transl. Oncol. 2012, 5, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkala, E.; Sollier-Christen, E.; Renier, C.; Rosàs-Canyelles, E.; Che, J.; Heirich, K.; Duncombe, T.A.; Vlassakis, J.; Yamauchi, K.A.; Huang, H.; et al. Profiling protein expression in circulating tumour cells using microfluidic western blotting. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, D.T. Single-cell analysis of circulating tumor cells as a window into tumor heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2016, 158, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimir-Bauer, S.; Hoffmann, O.; Wallwiener, D.; Kimmig, R.; Fehm, T. Expression of stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in primary breast cancer patients with circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensler, M.; Van Curov A, I.; Becht, E.; Rej Palata, O.; Strnad, P.; Tesa Rov A E, P.; Cabi Nakov A E, M.; Svec, D.; Kubista, M.; Bartu Nkov A, J.R.; et al. Gene expression profiling of circulating tumor cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from breast cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2015, 5, e1102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, B.; Tewes, M.; Fehm, T.; Hauch, S.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-, S. Stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers are frequently overexpressed in circulating tumor cells of metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2009, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, C.; Larios, J.M.; Muñiz, M.C.; Aung, K.; Cannell, E.M.; Darga, E.P.; Kidwell, K.M.; Thomas, D.G.; Tokudome, N.; Brown, M.E.; et al. Heterogeneous estrogen receptor expression in circulating tumor cells suggests diverse mechanisms of fulvestrant resistance. Mol. Oncol. 2016, 10, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, R.; Fernandez, A.; Sanchez-Rovira, P.; Salido, M.; Rodríguez, M.; García-Puche, J.L.; Macià, M.; Corominas, J.M.; Delgado-Rodriguez, M.; Gonzalez, L.; et al. Biomarkers characterization of circulating tumour cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehm, T.; Hoffmann, O.; Aktas, B.; Becker, S.; Solomayer, E.F.; Wallwiener, D.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-bauer, S. Detection and characterization of circulating tumor cells in blood of primary breast cancer patients by RT-PCR and comparison to status of bone marrow disseminated cells. Br Can. Res. 2009, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehm, T.; Müller, V.; Aktas, B.; Janni, W.; Schneeweiss, A.; Stickeler, E.; Lattrich, C.; Löhberg, C.R.; Solomayer, E.; Rack, B.; et al. HER2 status of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a prospective, multicenter trial. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 124, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Challenges in circulating tumour cell research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beije, N.; Onstenk, W.; Kraan, J.; Sieuwerts, A.M.; Hamberg, P.; Dirix, L.Y.; Brouwer, A.; de Jongh, F.E.; Jager, A.; Seynaeve, C.M.; et al. Prognostic impact of HER2 and ER status of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients with a HER2-negative primary tumor. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallwiener, M.; Hartkopf, A.D.; Riethdorf, S.; Nees, J.; Sprick, M.R.; Schönfisch, B.; Taran, F.-A.; Heil, J.; Sohn, C.; Pantel, K.; et al. The impact of HER2 phenotype of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: A retrospective study in 107 patients. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onstenk, W.; Sieuwerts, A.M.; Weekhout, M.; Mostert, B.; Reijm, E.A.; van Deurzen, C.H.M.; Bolt-de Vries, J.B.; Peeters, D.J.; Hamberg, P.; Seynaeve, C.; et al. Gene expression profiles of circulating tumor cells versus primary tumors in metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 362, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, N.; Nakamura, S.; Tokuda, Y.; Shimoda, Y.; Yagata, H.; Yoshida, A.; Ota, H.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Cristofanilli, M.; Ueno, N.T. Prognostic value of HER2-positive circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 17, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chang, C.-J.; Yeh, K.-Y.; Chang, P.-H.; Huang, J.-S. The prognostic value of her2-positive circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Breast Cancer 2017, 17, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, C.; Muñiz, M.C.; Thomas, D.G.; Griffith, K.A.; Kidwell, K.M.; Tokudome, N.; Brown, M.E.; Aung, K.; Miller, M.C.; Blossom, D.L.; et al. Development of circulating tumor cell-endocrine therapy index in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2487–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizkova, M.; Dujaric, M.-E.; Lehmann-Che, J.; Scott, V.; Tembo, O.; Asselain, B.; Pierga, J.-Y.; Marty, M.; de Cremoux, P.; Spyratos, F.; et al. Outcome impact of PIK3CA mutations in HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1807–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzer, B.; Medoro, G.; Pasch, S.; Fontana, F.; Zorzino, L.; Pestka, A.; Andergassen, U.; Meier-Stiegen, F.; Czyz, Z.T.; Alberter, B.; et al. Molecular profiling of single circulating tumor cells with diagnostic intention. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 1371–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punnoose, E.A.; Atwal, S.K.; Spoerke, J.M.; Savage, H.; Pandita, A.; Yeh, R.-F.; Pirzkall, A.; Fine, B.M.; Amler, L.C.; Chen, D.S.; et al. Molecular biomarker analyses using circulating tumor cells. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frithiof, H.; Aaltonen, K.; Rydén, L. A FISH-based method for assessment of HER-2 amplification status in breast cancer circulating tumor cells following CellSearch isolation. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2016, 9, 7095–7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.A.; Pham, T.; Wong, K.L.; Scoggin, J.; Sales, E.V.; Clarin, T.; Pircher, T.J.; Mikolajczyk, S.D.; Cotter, P.D.; Bischoff, F.Z. FISH-based determination of HER2 status in circulating tumor cells isolated with the microfluidic CEETM platform. Cancer Genet. 2011, 204, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.-C.; Cottu, P.; Dubot, C.; Venat-Bouvet, L.; Lortholary, A.; Bourgeois, H.; Bollet, M.; Servent Hanon, V.; Luporsi-Gely, E.; Espie, M.; et al. 117PAnti-HER2 therapy efficacy in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer with HER2-amplified circulating tumor cells: Results of the CirCe T-DM1 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, mdx363.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, R.P.L.; Raba, K.; Schmidt, O.; Honisch, E.; Meier-Stiegen, F.; Behrens, B.; Möhlendick, B.; Fehm, T.; Neubauer, H.; Klein, C.A.; et al. Genomic high-resolution profiling of single CKpos/CD45neg flow-sorting purified circulating tumor cells from patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Chem. 2014, 60, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, C.; Fernandez, S.V.; Fittipaldi, P.; Dempsey, P.W.; Ruth, K.J.; Cristofanilli, M.; Katherine Alpaugh, R. Mutational studies on single circulating tumor cells isolated from the blood of inflammatory breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 163, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Benali-Furet, N.; Uzan, G.; Znaty, A.; Ye, Z.; Paolillo, C.; Wang, C.; Austin, L.; Rossi, G.; Fortina, P.; et al. Detection and characterization of circulating tumor associated cells in metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, F.; Rotunno, G.; Salvianti, F.; Galardi, F.; Pestrin, M.; Gabellini, S.; Simi, L.; Mancini, I.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Pazzagli, M.; et al. Mutational analysis of single circulating tumor cells by next generation sequencing in metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 26107–26119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolaki, S.; Perraki, M.; Kallergi, G.; Kafousi, M.; Papadopoulos, S.; Kotsakis, A.; Pallis, A.; Xenidis, N.; Kalmanti, L.; Kalbakis, K.; et al. Detection of occult HER2 mRNA-positive tumor cells in the peripheral blood of patients with operable breast cancer: Evaluation of their prognostic relevance. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 117, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiadis, M.; Kallergi, G.; Ntoulia, M.; Perraki, M.; Apostolaki, S.; Kafousi, M.; Chlouverakis, G.; Stathopoulos, E.; Lianidou, E.; Georgoulias, V.; et al. Prognostic value of the molecular detection of circulating tumor cells using a multimarker reverse transcription-pcr assay for cytokeratin 19, mammaglobin a, and her2 in early breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2593–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiadis, M.; Rothé, F.; Chaboteaux, C.; Durbecq, V.; Rouas, G.; Criscitiello, C.; Metallo, J.; Kheddoumi, N.; Singhal, S.K.; Michiels, S.; et al. HER2-positive circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e15624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, A.; Ahrends, T.; Wełnicka-Jaśkiewicz, M.; Seroczyńska, B.; Skokowski, J.; Jaśkiewicz, J.; Szade, J.; Biernat, W.; Zaczek, A.J. Expression of epithelial to mesenchymal transition-related markers in lymph node metastases as a surrogate for primary tumor metastatic potential in breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Sarkar, F.H.; Ahmed, Q.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Nahleh, Z.A.; Semaan, A.; Sakr, W.; Munkarah, A.; Ali-Fehmi, R. Molecular markers of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition are associated with tumor aggressiveness in breast carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2011, 4, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.E.; Scott, J.H.; Wolf, D.M.; Novak, P.; Punj, V.; Magbanua, M.J.M.; Zhu, W.; Mineyev, N.; Haqq, C.M.; Crothers, J.R.; et al. Expression profiling of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 149, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, T.B.; Kaur, P.; Ring, A.; Schechter, N.; Lang, J.E. Challenges in using liquid biopsies for gene expression profiling. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7036–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieuwerts, A.M.; Mostert, B.; Bolt-De Vries, J.; Peeters, D.; De Jongh, F.E.; Stouthard, J.M.L.; Dirix, L.Y.; Van Dam, P.A.; Van Galen, A.; De Weerd, V.; et al. mRNA and microRNA expression profiles in circulating tumor cells and primary tumors of metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 3600–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, E.; Callari, M.; Reduzzi, C.; D’Aiuto, F.; Mariani, G.; Generali, D.; Pierotti, M.A.; Daidone, M.G.; Cappelletti, V. Gene expression profiling of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Clin. Chem. 2015, 61, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, K.E.; Novosadová, V.; Bendahl, P.; Graffman, C.; Larsson, A.; Rydén, L. Molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells from patients with metastatic breast cancer reflects evolutionary changes in gene expression under the pressure of systemic therapy Patient cohort. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 45544–45565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.M.; Tan, K.M.-L.; Chua, H.W.; Huang, M.-C.; Cheong, W.C.; Li, M.-H.; Tucker, S.; Koay, E.S.-C. Paper-based MicroRNA expression profiling from plasma and circulating tumor cells. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, C.; Plummer, P.N.; Jovanovic, L.; McInnes, L.M.; Wescott, D.; Saunders, C.M.; Schneeweiss, A.; Wallwiener, M.; Nelson, C.; Spring, K.J.; et al. Heterogeneity of miR-10b expression in circulating tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Ory, B.; Lamoureux, F.; Heymann, M.-F.; Heymann, D.; Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Ory, B.; Lamoureux, F.; Heymann, M.-F.; Heymann, D. Tumour heterogeneity: The key advantages of single-cell analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, N.A.; Yussif, S.M. Ki-67 as a prognostic marker according to breast cancer molecular subtype. Cancer Biol. Med. 2016, 13, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niikura, N.; Masuda, S.; Kumaki, N.; Xiaoyan, T.; Terada, M.; Terao, M.; Iwamoto, T.; Oshitanai, R.; Morioka, T.; Tuda, B.; et al. Prognostic significance of the Ki67 scoring categories in breast cancer subgroups. Clin. Breast Cancer 2014, 14, 323–329.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould Rothberg, B.E.; Bracken, M.B. E-cadherin immunohistochemical expression as a prognostic factor in infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2006, 100, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P.A.; Kirschmann, D.A.; Cerhan, J.R.; Folberg, R.; Seftor, E.A.; Sellers, T.A.; Hendrix, M.J. Association between keratin and vimentin expression, malignant phenotype, and survival in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2698–2703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bulfoni, M.; Gerratana, L.; Del Ben, F.; Marzinotto, S.; Sorrentino, M.; Turetta, M.; Scoles, G.; Toffoletto, B.; Isola, M.; Beltrami, C.A.; et al. In patients with metastatic breast cancer the identification of circulating tumor cells in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is associated with a poor prognosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Hennessy, B.T.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Sahin, A.; Liu, W.; Ju, Z.; Carey, M.S.; Myhre, S.; Speers, C.; Deng, L.; et al. Functional proteomics can define prognosis and predict pathologic complete response in patients with breast cancer. Clin. Proteomics 2011, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Sahin, A.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Mills, G.B.; Do, K.-A.; Meric-Bernstam, F. Functional proteomics characterization of residual breast cancer after neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, I.C.; Voet, T. Single cell genomics: Advances and future perspectives. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, S.V.; Bingham, C.; Fittipaldi, P.; Austin, L.; Palazzo, J.; Palmer, G.; Alpaugh, K.; Cristofanilli, M. TP53 mutations detected in circulating tumor cells present in the blood of metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestrin, M.; Salvianti, F.; Galardi, F.; De Luca, F.; Turner, N.; Malorni, L.; Pazzagli, M.; Di Leo, A.; Pinzani, P. Heterogeneity of PIK3CA mutational status at the single cell level in circulating tumor cells from metastatic breast cancer patients. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, G.; Krishnakumar, S.; Powell, A.A.; Zhang, H.; Mindrinos, M.N.; Telli, M.L.; Davis, R.W.; Jeffrey, S.S. Single cell mutational analysis of PIK3CA in circulating tumor cells and metastases in breast cancer reveals heterogeneity, discordance, and mutation persistence in cultured disseminated tumor cells from bone marrow. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, L.M.; Kindelberger, D.W.; Ligon, A.H.; Capelletti, M.; Fiorentino, M.; Loda, M.; Cibas, E.S.; Jänne, P.A.; Krop, I.E. Improving the yield of circulating tumour cells facilitates molecular characterisation and recognition of discordant HER2 amplification in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoletti, C.; Cani, A.K.; Larios, J.M.; Hovelson, D.H.; Aung, K.; Darga, E.P.; Cannell, E.M.; Baratta, P.J.; Liu, C.-J.; Chu, D.; et al. Comprehensive mutation and copy number profiling in archived circulating breast cancer tumor cells documents heterogeneous resistance mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berns, K.; Horlings, H.M.; Hennessy, B.T.; Madiredjo, M.; Hijmans, E.M.; Beelen, K.; Linn, S.C.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Hauptmann, M.; et al. A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2007, 12, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandarlapaty, S.; Sakr, R.A.; Giri, D.; Patil, S.; Heguy, A.; Morrow, M.; Modi, S.; Norton, L.; Rosen, N.; Hudis, C.; et al. Frequent mutational activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 6784–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, L.; Gaur, S.; Zhang, K.; Wu, X.; Yuan, Y.-C.; Li, H.; Hu, S.; Weng, Y.; Yen, Y. Mutants TP53 p.R273H and p.R273C but not p.R273G enhance cancer cell malignancy. Hum. Mutat. 2014, 35, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, R.; Kavuri, S.M.; Searleman, A.C.; Shen, W.; Shen, D.; Koboldt, D.C.; Monsey, J.; Goel, N.; Aronson, A.B.; Li, S.; et al. Activating HER2 mutations in HER2 gene amplification negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.B.L.; Leal, M.F.; de Souza, C.R.T.; Montenegro, R.C.; Rey, J.A.; Carvalho, A.A.; Assumpção, P.P.; Khayat, A.S.; Pinto, G.R.; Demachki, S.; et al. Prognostic and predictive significance of myc and kras alterations in breast cancer from women treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aas, T.; Børresen, A.-L.; Geisler, S.; Smith-Sørensen, B.; Johnsen, H.; Varhaug, J.E.; Akslen, L.A.; Lønning, P.E. Specific P53 mutations are associated with de novo resistance to doxorubicin in breast cancer patients. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berns, E.M.; Foekens, J.A.; Vossen, R.; Look, M.P.; Devilee, P.; Henzen-Logmans, S.C.; van Staveren, I.L.; van Putten, W.L.; Inganäs, M.; Meijer-van Gelder, M.E.; et al. Complete sequencing of TP53 predicts poor response to systemic therapy of advanced breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 2155–2162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kandioler-Eckersberger, D.; Ludwig, C.; Rudas, M.; Kappel, S.; Janschek, E.; Wenzel, C.; Schlagbauer-Wadl, H.; Mittlböck, M.; Gnant, M.; Steger, G.; et al. TP53 mutation and p53 overexpression for prediction of response to neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muller, P.A.J.; Vousden, K.H. Mutant p53 in cancer: New functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, J.E.; Magbanua, M.J.M.; Scott, J.H.; Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Wang, G.; Federman, S.; Esserman, L.J.; Park, J.W.; Haqq, C.M. A comparison of RNA amplification techniques at sub-nanogram input concentration. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehm, T.; Becker, S.; Duerr-Stoerzer, S.; Sotlar, K.; Mueller, V.; Wallwiener, D.; Lane, N.; Solomayer, E.; Uhr, J. Determination of HER2 status using both serum HER2 levels and circulating tumor cells in patients with recurrent breast cancer whose primary tumor was HER2 negative or of unknown HER2 status. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9, R74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewes, M.; Aktas, B.; Welt, A.; Mueller, S.; Hauch, S.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-Bauer, S. Molecular profiling and predictive value of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: An option for monitoring response to breast cancer related therapies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 115, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Ma, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, S.; Xiao, R.; Yuan, L.; Sun, X.; Yi, Z.; Yang, H.; Xu, B. Analysis of the hormone receptor status of circulating tumor cell subpopulations based on epithelial-mesenchymal transition: A proof-of-principle study on the heterogeneity of circulating tumor cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 65993–66002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Christofori, G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009, 28, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.J.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradilone, A.; Raimondi, C.; Nicolazzo, C.; Petracca, A.; Gandini, O.; Vincenzi, B.; Naso, G.; Aglianò, A.M.; Cortesi, E.; Gazzaniga, P. Circulating tumour cells lacking cytokeratin in breast cancer: The importance of being mesenchymal. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulos, P.A.; Polioudaki, H.; Agelaki, S.; Kallergi, G.; Saridaki, Z.; Mavroudis, D.; Georgoulias, V. Circulating tumor cells with a putative stem cell phenotype in peripheral blood of patients with breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010, 288, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Settleman, J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: An emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene 2010, 29, 4741–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seton-Rogers, S. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: Untangling EMT’s functions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Marengo, M.S.; Oltean, S.; Kemeny, G.; Bitting, R.L.; Turnbull, J.D.; Herold, C.I.; Marcom, P.K.; George, D.J.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A. Circulating tumor cells from patients with advanced prostate and breast cancer display both epithelial and mesenchymal markers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagiannis, G.S.; Goswami, S.; Jones, J.G.; Oktay, M.H.; Condeelis, J.S. Signatures of breast cancer metastasis at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredemeier, M.; Edimiris, P.; Tewes, M.; Mach, P.; Aktas, B.; Schellbach, D.; Wagner, J.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-Bauer, S. Establishment of a multimarker qPCR panel for the molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells in blood samples of metastatic breast cancer patients during the course of palliative treatment. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41677–41690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boral, D.; Vishnoi, M.; Liu, H.N.; Yin, W.; Sprouse, M.L.; Scamardo, A.; Hong, D.S.; Tan, T.Z.; Thiery, J.P.; Chang, J.C.; et al. Molecular characterization of breast cancer CTCs associated with brain metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsialou, A.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Whitney, K.; Goswami, S.; Kenny, P.A.; Condeelis, J.S. Selective gene-expression profiling of migratory tumor cells in vivo predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, T.J.; Roepman, P.; Naume, B.; van’t Veer, L.J. A prognostic gene expression profile that predicts circulating tumor cell presence in breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, C. Genomic profiling of breast cancers. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 27, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorges, T.M.; Kuske, A.; Röck, K.; Mauermann, O.; Müller, V.; Peine, S.; Verpoort, K.; Novosadova, V.; Kubista, M.; Riethdorf, S.; et al. Accession of tumor heterogeneity by multiplex transcriptome profiling of single circulating tumor cells. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navin, N.; Kendall, J.; Troge, J.; Andrews, P.; Rodgers, L.; McIndoo, J.; Cook, K.; Stepansky, A.; Levy, D.; Esposito, D.; et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature 2011, 472, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, A.A.; Talasaz, A.H.; Zhang, H.; Coram, M.A.; Reddy, A.; Deng, G.; Telli, M.L.; Advani, R.H.; Carlson, R.W.; Mollick, J.A.; et al. Single cell profiling of circulating tumor cells: Transcriptional heterogeneity and diversity from breast cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, S.S.; Kester, L.; Spanjaard, B.; Bienko, M.; van Oudenaarden, A. Integrated genome and transcriptome sequencing of the same cell. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaulay, I.C.; Haerty, W.; Kumar, P.; Li, Y.I.; Hu, T.X.; Teng, M.J.; Goolam, M.; Saurat, N.; Coupland, P.; Shirley, L.M.; et al. G&T-seq: Parallel sequencing of single-cell genomes and transcriptomes. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 519–522. [Google Scholar]

- Genshaft, A.S.; Li, S.; Gallant, C.J.; Darmanis, S.; Prakadan, S.M.; Ziegler, C.G.K.; Lundberg, M.; Fredriksson, S.; Hong, J.; Regev, A.; et al. Multiplexed, targeted profiling of single-cell proteomes and transcriptomes in a single reaction. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbahce, N.; Magbanua, M.J.M.; Chin, R.; Agarwal, M.R.; Luo, X.; Liu, J.; Hayden, D.M.; Mao, Q.; Ciotlos, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Quantitative whole genome sequencing of circulating tumor cells enables personalized combination therapy of metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4530–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilicic, T.; Kim, J.K.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Bagger, F.O.; McCarthy, D.J.; Marioni, J.C.; Teichmann, S.A. Classification of low quality cells from single-cell RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Singh, A.; Kulkarni, R.V. Transcriptional bursting in gene expression: Analytical results for general stochastic models. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S. Tuning noise in gene expression. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2015, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegenhain, C.; Vieth, B.; Parekh, S.; Heyn, H. Comparative analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing methods. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 631–643.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analyte | Marker | Prognostic/Predictive Value in IBC-Primary Tumour | Successfully Applied in CTCs | Prognostic or Predictive Value when Examined in CTCs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | HER2 amplification | Strong predictive value. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | No confirmed prognostic/predictive value in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with ado-trastuzumab emtansine [111]. | [112,113,114,115,116] |

| PIK3CA gain-of-function mutation | Prognostic factor linked to good prognosis; not applied in routine clinical practice. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Not assessed. | [112,117,118] | |

| TP53 loss-of-function mutation | Prognostic factor linked to poor prognosis; no predictive value in routine clinical practice. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Not assessed. | [117,119] | |

| RB1 | Prognostic factor linked to poor prognosis. Predictive value—low RB1 expression in triple negative/ER-negative breast cancers related to good prognosis in patients treated with chemotherapy. | Yes, can be assessed. | Not assessed. | [118] | |

| ESR1 mutations | Prognostic factor linked to poor prognosis, potentially to be applied in clinics as a negative predictive factor (hormone resistance). | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Not assessed. | [119] | |

| Ion AmpliSeq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 | Not assessed. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Not assessed. | [10,120] | |

| RNA | ESR1/PGR | Both receptors routinely examined at protein level. Discrepancies between mRNA and protein expression frequently observed, but mRNA evaluation also shown of prognostic/ predictive value. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Prognostic value like in primary tumour, discrepant results of predictive value. | [93,105,107]. |

| HER2 | Discrepancies between mRNA and protein levels seen in nearly 25% of patients. Protein examination routinely applied in clinics. mRNA also of both prognostic and predictive value. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | HER2-positive CTCs are linked to poor prognosis in terms of both OS and PFS. | [108,109,121,122,123] | |

| EMT pathway molecules | Association between high levels of mesenchymal markers frequently reported. No predictive value or validated clinical application. | Yes, but efficiency of protocol/s still to be improved. | High frequency of mesenchymal CTCs linked to poor prognosis. No data on predictive value. | [62,97,99,124,125] | |

| PAM50 | Prognostic and predictive value comparable to standard predictive factors, useful in clinical practice. | No report on coverage of all genes; single reports on partial assessment of the signature | Not assessed. | [91,126,127,128] | |

| Prosigna | Routinely applied predictive panel in clinics. | No, cannot be robustly applied. | Not assessed. | [126,127] | |

| Other panels, including EndoPredict, Mammaprint, OncotypeDx, Breast Cancer Index | Each panel designed to predict outcome; prognostic and predictive values of various panels similarly high across several comparing studies; routinely applied in clinics. | No reports so far. | Not assessed. | [60,126,129,130] | |

| microRNAs | Some panels of prognostic value when measured in primary tumour, but the known panels mostly applied for free-circulating microRNAs. | On-going research to resolve technical issues. | Not assessed. | [128,131,132,133] | |

| Protein | ER, PR | The most significant prognostic and predictive factors applied in clinics. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Prognostic value. | [11,101,103,105,106,107,108] |

| HER2 | One of the key prognostic and predictive factors applied in clinics. | Yes, can be robustly assessed. | Poor prognostic value in terms of PFS in patients with HER2-positive CTCs in comparison to patients with HER2-negative CTCs, no strong prognostic value regarding OS. | [101,105,106,109] | |

| Ki67 | One of the key prognostic and predictive factors applied in clinics. | Yes, but some technical difficulties still to be overcome. | Not assessed. | [134,135] | |

| EMT pathway molecules | Prognostic role of E-cadherin, vimentin and keratins. | Yes, can be robustly assessed | EMT activation related with reduced PFS and OS in metastatic patients. | [16,136,137,138] | |

| Proteomic panels | Prognostic significance of breast cancer subtypes identified by a multi-protein marker set. | Yes, can be assessed. | Not assessed. Used in basic science research. | [139,140] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Braun, M.; Markiewicz, A.; Kordek, R.; Sądej, R.; Romańska, H. Profiling of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Circulating Tumour Cells—Are We Ready for the ‘Liquid’ Revolution? Cancers 2019, 11, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020143

Braun M, Markiewicz A, Kordek R, Sądej R, Romańska H. Profiling of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Circulating Tumour Cells—Are We Ready for the ‘Liquid’ Revolution? Cancers. 2019; 11(2):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020143

Chicago/Turabian StyleBraun, Marcin, Aleksandra Markiewicz, Radzisław Kordek, Rafał Sądej, and Hanna Romańska. 2019. "Profiling of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Circulating Tumour Cells—Are We Ready for the ‘Liquid’ Revolution?" Cancers 11, no. 2: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020143

APA StyleBraun, M., Markiewicz, A., Kordek, R., Sądej, R., & Romańska, H. (2019). Profiling of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Circulating Tumour Cells—Are We Ready for the ‘Liquid’ Revolution? Cancers, 11(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020143