Epigenetic Drugs for Cancer and microRNAs: A Focus on Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epigenetic Drugs in Cancer

2.1. Histone Deacetylase

2.2. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

2.3. FDA-Approved Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

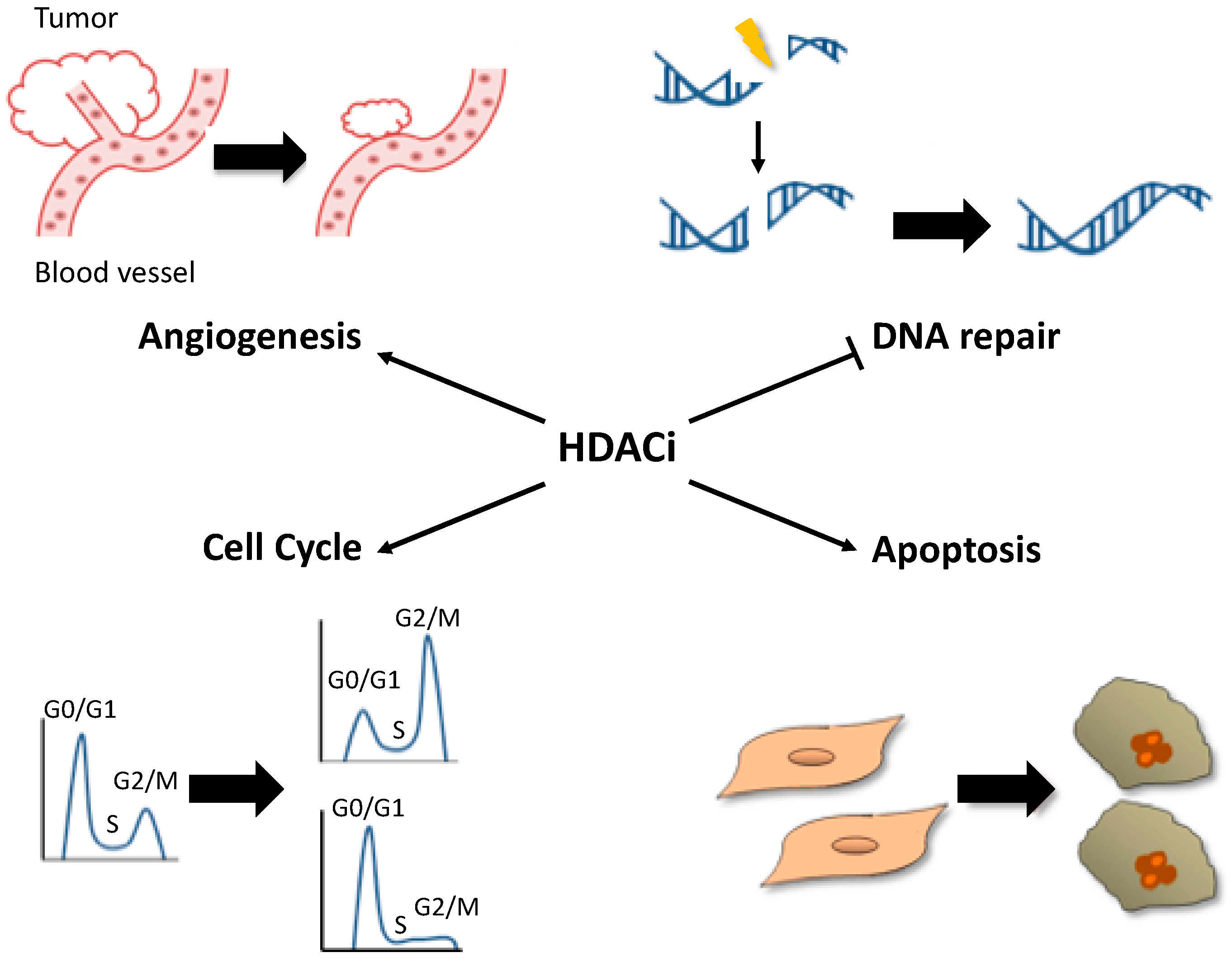

3. Effect of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors on Tumor Cells

3.1. Cell Cycle

3.2. Cell Death

3.3. Angiogenesis

3.4. DNA Damage

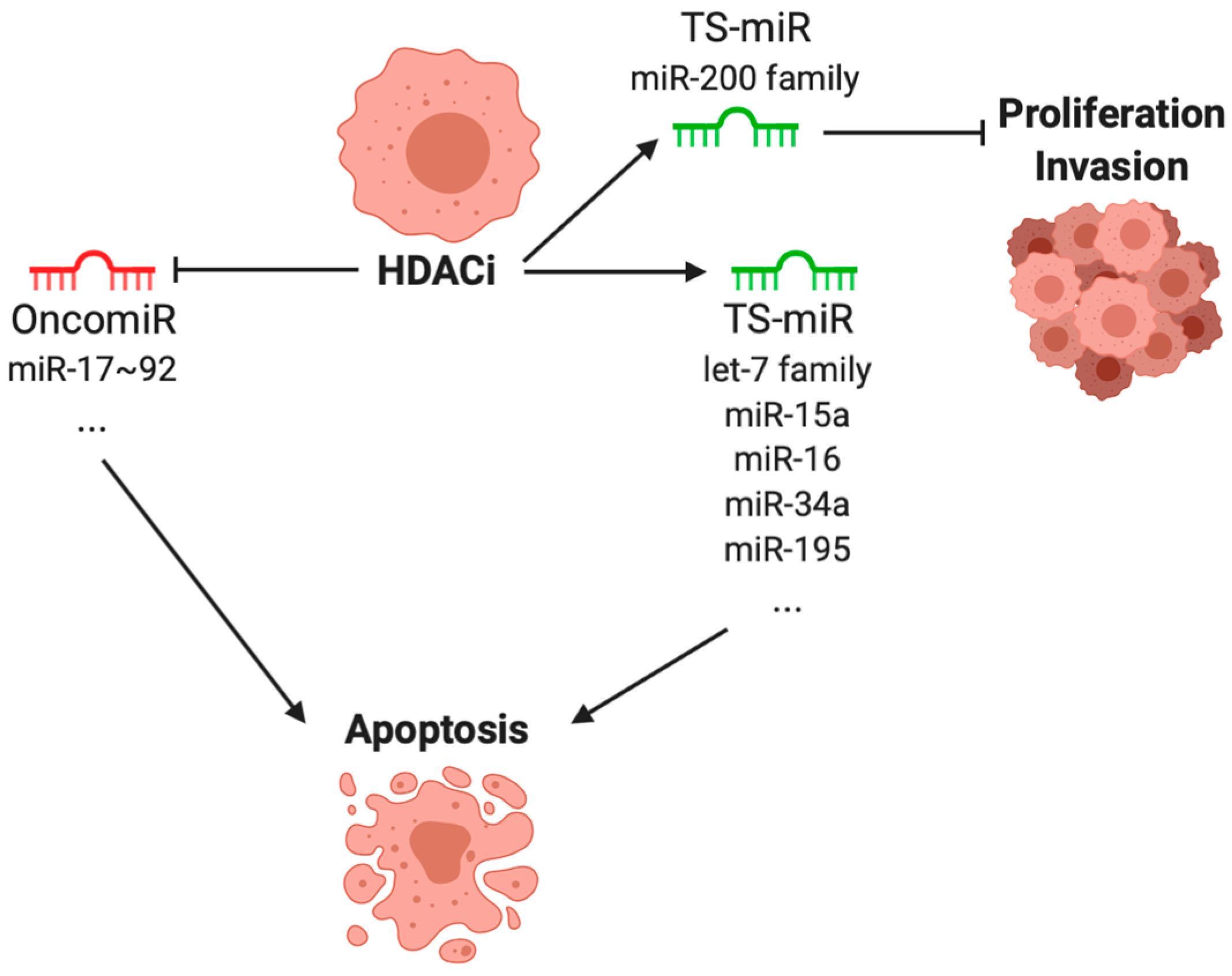

4. Effect of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors on microRNA Expressions in Cancer

4.1. microRNAs Dysregulated in Cancer

4.2. miRNA Regulated by Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

4.2.1. FDA-Approved HDACi and miRNAs

4.2.2. Other HDACi and miRNAs

4.2.3. Clinical Relevance

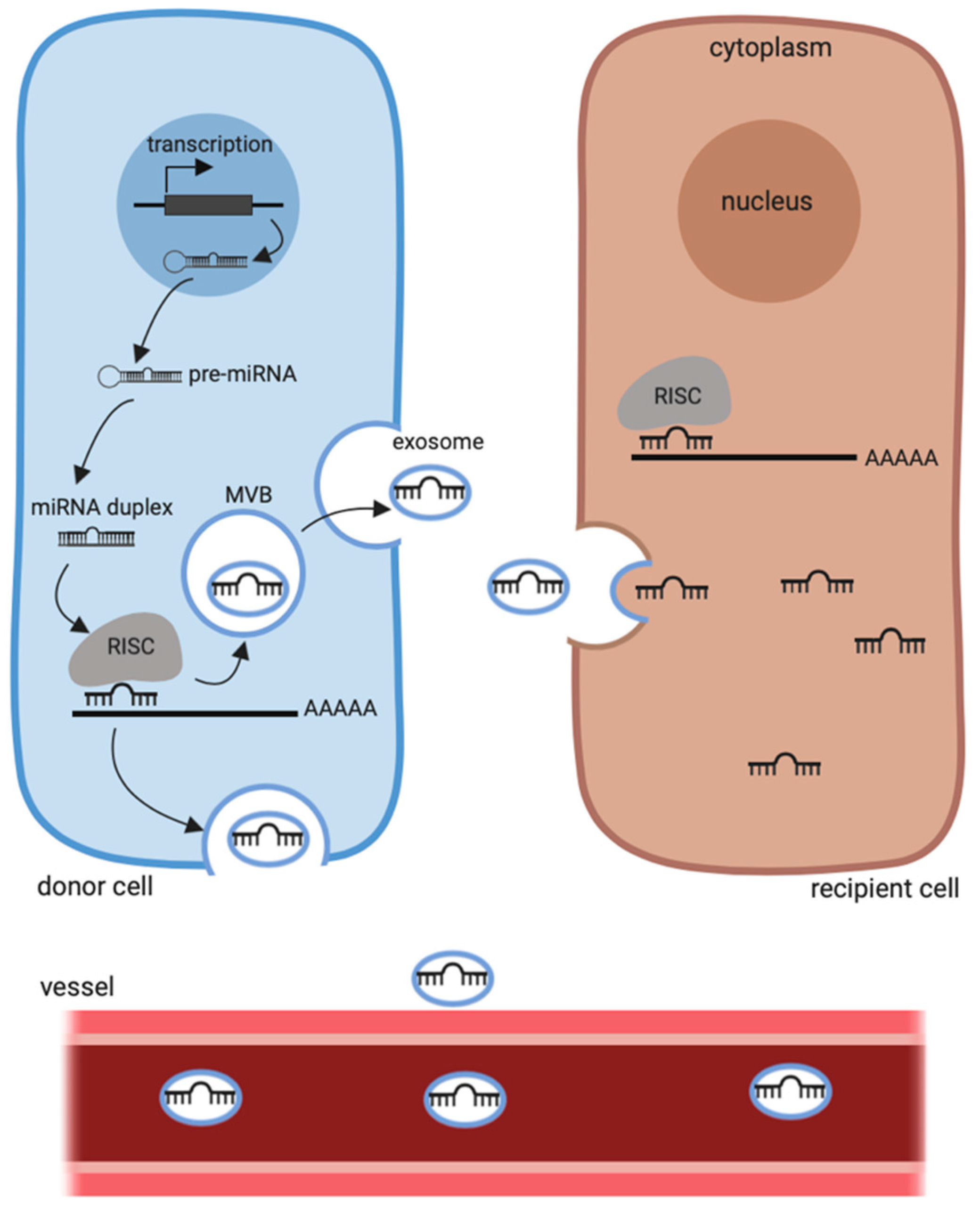

4.3. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and Circulating miRNAs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbach, M.; Schwanhäusser, B.; Thierfelder, N.; Fang, Z.; Khanin, R.; Rajewsky, N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 2008, 455, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, R.C.; Farh, K.K.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zen, K.; Zhang, C.-Y. Secreted microRNAs: A new form of intercellular communication. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Xu, H.; Gong, W.; Deng, W. The Tumor Cytosol miRNAs, Fluid miRNAs, and Exosome miRNAs in Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tan, R.; Wong, L.; Fekete, R.; Halsey, J. Quantitation of microRNAs by real-time RT-qPCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 687, 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, A.D.; Issa, J.-P.J. The promise of epigenetic therapy: Reprogramming the cancer epigenome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2017, 42, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seto, E.; Yoshida, M. Erasers of Histone Acetylation: The Histone Deacetylase Enzymes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a018713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Fischle, W.; Verdin, E.; Greene, W.C. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science 2001, 293, 1653–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaughan, L.; Logan, I.R.; Cook, S.; Neal, D.E.; Robson, C.N. Tip60 and histone deacetylase 1 regulate androgen receptor activity through changes to the acetylation status of the receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 25904–25913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Roeder, R.G. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell 1997, 90, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.W.; Bae, M.K.; Ahn, M.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Sohn, T.K.; Bae, M.H.; Yoo, M.A.; Song, E.J.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, K.W. Regulation and destabilization of HIF-1alpha by ARD1-mediated acetylation. Cell 2002, 111, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Balbas, M.A.; Bauer, U.M.; Nielsen, S.J.; Brehm, A.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of E2F1 activity by acetylation. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.H.; Du, Y.; Ard, P.G.; Phillips, C.; Carella, B.; Chen, C.J.; Rakowski, C.; Chatterjee, C.; Lieberman, P.M.; Lane, W.S.; et al. The c-MYC oncoprotein is a substrate of the acetyltransferases hGCN5/PCAF and TIP60. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 10826–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Fu, M.; Angeletti, R.H.; Siconolfi-Baez, L.; Reutens, A.T.; Albanese, C.; Lisanti, M.P.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; Kato, S.; Hopp, T.; et al. Direct acetylation of the estrogen receptor alpha hinge region by p300 regulates transactivation and hormone sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 18375–18383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, J.J.; Murphy, P.J.; Gaillard, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J.T.; Nicchitta, C.V.; Yoshida, M.; Toft, D.O.; Pratt, W.B.; Yao, T.P. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.L.; Guan, Y.J.; Chatterjee, D.; Chin, Y.E. Stat3 dimerization regulated by reversible acetylation of a single lysine residue. Science 2005, 307, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Caron, C.; Matthias, G.; Hess, D.; Khochbin, S.; Matthias, P. HDAC-6 interacts with and deacetylates tubulin and microtubules in vivo. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, N.; Bertrand, P. Interpreting clinical assays for histone deacetylase inhibitors. Cancer Manag. Res. 2011, 3, 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, P.A. Discovery and development of SAHA as an anticancer agent. Oncogene 2007, 26, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, R.M. Belinostat: First global approval. Drugs 2014, 74, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P.G.; Laubach, J.P.; Lonial, S.; Moreau, P.; Yoon, S.S.; Hungria, V.T.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Beksac, M.; Alsina, M.; San-Miguel, J.F. Panobinostat: A novel pan-deacetylase inhibitor for the treatment of relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2015, 15, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaecke, T.; Papeleu, P.; Elaut, G.; Rogiers, V. Trichostatin A-like hydroxamate histone deacetylase inhibitors as therapeutic agents: Toxicological point of view. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, C.; Rahman, F.; Piekarz, R.; Peer, C.; Frye, R.; Robey, R.W.; Gardner, E.R.; Figg, W.D.; Bates, S.E. Romidepsin: A new therapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and a potential therapy for solid tumors. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2010, 10, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.P.; Foss, F.F. Romidepsin for the Treatment of Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. Oncologist 2015, 20, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, B.S.; Johnson, J.R.; Cohen, M.H.; Justice, R.; Pazdur, R. FDA approval summary: Vorinostat for treatment of advanced primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncologist 2007, 12, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, L.M.; Kindler, H.L.; Calvert, H.; Manegold, C.; Tsao, A.S.; Fennell, D.; Ohman, R.; Plummer, R.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Fukuoka, K.; et al. Vorinostat in patients with advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma who have progressed on previous chemotherapy (VANTAGE-014): A phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, H.; Kim, Y.B.; Terano, H.; Yoshida, M.; Horinouchi, S. FR901228, a potent antitumor antibiotic, is a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 241, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, H.; Nakajima, H.; Hori, Y.; Goto, T.; Okuhara, M. Action of FR901228, a novel antitumor bicyclic depsipeptide produced by Chromobacterium violaceum no. 968, on Ha-ras transformed NIH3T3 cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1994, 58, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarz, R.L.; Frye, R.; Turner, M.; Wright, J.J.; Allen, S.L.; Kirschbaum, M.H.; Zain, J.; Prince, H.M.; Leonard, J.P.; Geskin, L.J.; et al. Phase II multi-institutional trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin as monotherapy for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5410–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiffier, B.; Pro, B.; Prince, H.M.; Foss, F.; Sokol, L.; Greenwood, M.; Caballero, D.; Borchmann, P.; Morschhauser, F.; Wilhelm, M.; et al. Results from a pivotal, open-label, phase II study of romidepsin in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma after prior systemic therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, O.A.; Horwitz, S.; Masszi, T.; Van Hoof, A.; Brown, P.; Doorduijn, J.; Hess, G.; Jurczak, W.; Knoblauch, P.; Chawla, S.; et al. Belinostat in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: Results of the Pivotal Phase II BELIEF (CLN-19) Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foss, F.; Advani, R.; Duvic, M.; Hymes, K.B.; Intragumtornchai, T.; Lekhakula, A.; Shpilberg, O.; Lerner, A.; Belt, R.J.; Jacobsen, E.D.; et al. A Phase II trial of Belinostat (PXD101) in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 168, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, S.S.; Belani, C.P.; Ruel, C.; Frankel, P.; Gitlitz, B.; Koczywas, M.; Espinoza-Delgado, I.; Gandara, D. Phase II study of belinostat (PXD101), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for second line therapy of advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009, 4, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San-Miguel, J.F.; Hungria, V.T.; Yoon, S.S.; Beksac, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Elghandour, A.; Jedrzejczak, W.W.; Gunther, A.; Nakorn, T.N.; Siritanaratkul, N.; et al. Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Bishayee, A.; Pandey, A.K. Targeting Histone Deacetylases with Natural and Synthetic Agents: An Emerging Anticancer Strategy. Nutrients 2018, 10, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckschlager, T.; Plch, J.; Stiborova, M.; Hrabeta, J. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors as Anticancer Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottamal, M.; Zheng, S.; Huang, T.L.; Wang, G. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical studies as templates for new anticancer agents. Molecules 2015, 20, 3898–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, S.Y.; Meng, S.; Shei, A.; Hodin, R.A. p21(WAF1) is required for butyrate-mediated growth inhibition of human colon cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6791–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Deiry, W.S.; Tokino, T.; Velculescu, V.E.; Levy, D.B.; Parsons, R.; Trent, J.M.; Lin, D.; Mercer, W.E.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 1993, 75, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Yamashita, T.; Mariko, Y.; Nosaka, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Ando, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tsuruo, T.; Nakanishi, O. A synthetic inhibitor of histone deacetylase, MS-27-275, with marked in vivo antitumor activity against human tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4592–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, C.Y.; Ngo, L.; Xu, W.S.; Richon, V.M.; Marks, P.A. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor activation of p21WAF1 involves changes in promoter-associated proteins, including HDAC1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowa, Y.; Orita, T.; Minamikawa-Hiranabe, S.; Mizuno, T.; Nomura, H.; Sakai, T. Sp3, but not Sp1, mediates the transcriptional activation of the p21/WAF1/Cip1 gene promoter by histone deacetylase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 4266–4270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Condorelli, F.; Gnemmi, I.; Vallario, A.; Genazzani, A.A.; Canonico, P.L. Inhibitors of histone deacetylase (HDAC) restore the p53 pathway in neuroblastoma cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, L.; Chai, G.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Acetylation of p53 at lysine 373/382 by the histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide induces expression of p21(Waf1/Cip1). Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strait, K.A.; Dabbas, B.; Hammond, E.H.; Warnick, C.T.; Iistrup, S.J.; Ford, C.D. Cell cycle blockade and differentiation of ovarian cancer cells by the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A are associated with changes in p21, Rb, and Id proteins. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002, 1, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, V.L.; Williams, J.M.; Cogswell, J.P.; Mendenhall, M.; Zimmer, S.G. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote apoptosis and differential cell cycle arrest in anaplastic thyroid cancer cells. Thyroid 2001, 11, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florenes, V.A.; Skrede, M.; Jorgensen, K.; Nesland, J.M. Deacetylase inhibition in malignant melanomas: Impact on cell cycle regulation and survival. Melanoma Res. 2004, 14, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandy, T.E.; Shankar, S.; Ross, D.D.; Sausville, E.; Srivastava, R.K. Interactive effects of HDAC inhibitors and TRAIL on apoptosis are associated with changes in mitochondrial functions and expressions of cell cycle regulatory genes in multiple myeloma. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Sigua, C.; Tao, J.; Bali, P.; George, P.; Li, Y.; Wittmann, S.; Moscinski, L.; Atadja, P.; Bhalla, K. Cotreatment with histone deacetylase inhibitor LAQ824 enhances Apo-2L/tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand-induced death inducing signaling complex activity and apoptosis of human acute leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2580–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.R.; Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. HDAC inhibitors enhance the apoptosis-inducing potential of TRAIL in breast carcinoma. Oncogene 2005, 24, 4609–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Singh, T.R.; Fandy, T.E.; Luetrakul, T.; Ross, D.D.; Srivastava, R.K. Interactive effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors and TRAIL on apoptosis in human leukemia cells: Involvement of both death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 16, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacomino, G.; Medici, M.C.; Russo, G.L. Valproic acid sensitizes K562 erythroleukemia cells to TRAIL/Apo2L-induced apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2008, 28, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inoue, S.; Harper, N.; Walewska, R.; Dyer, M.J.; Cohen, G.M. Enhanced Fas-associated death domain recruitment by histone deacetylase inhibitors is critical for the sensitization of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 3088–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, G.M.; Newbold, A.; Johnstone, R.W. Intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway signaling as determinants of histone deacetylase inhibitor antitumor activity. Adv. Cancer Res. 2012, 116, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mie Lee, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; Jin Son, M.; Nakajima, H.; Jeong Kwon, H.; Kim, K.W. Inhibition of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis by FK228, a specific histone deacetylase inhibitor, via suppression of HIF-1alpha activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 300, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, H.; Murakami, H.; Ohshima, Y.; Murakami, M.; Yamazaki, I.; Tamura, Y.; Mima, T.; Satone, A.; Ide, W.; Hashimoto, I.; et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors such as sodium butyrate and trichostatin A inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion from human glioblastoma cells. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2002, 19, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasakawa, Y.; Naoe, Y.; Noto, T.; Inoue, T.; Sasakawa, T.; Matsuo, M.; Manda, T.; Mutoh, S. Antitumor efficacy of FK228, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, depends on the effect on expression of angiogenesis factors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 66, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgouras, D.; Becker, U.; Loitsch, S.; Stein, J. Modulation of angiogenesis-related protein synthesis by valproic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 316, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, U.; Kaiser, M.; Sterz, J.; Zavrski, I.; Jakob, C.; Fleissner, C.; Eucker, J.; Possinger, K.; Sezer, O. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reduce VEGF production and induce growth suppression and apoptosis in human mantle cell lymphoma. European J. Haematol. 2006, 76, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kwon, H.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Baek, J.H.; Jang, J.E.; Lee, S.W.; Moon, E.J.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.K.; Chung, H.Y.; et al. Histone deacetylases induce angiogenesis by negative regulation of tumor suppressor genes. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, D.Z.; Kachhap, S.K.; Collis, S.J.; Verheul, H.M.; Carducci, M.A.; Atadja, P.; Pili, R. Class II histone deacetylases are associated with VHL-independent regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 8814–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.T.; Hung, W.C. Inhibition of proliferation, sprouting, tube formation and Tie2 signaling of lymphatic endothelial cells by the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 30, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellebrekers, D.M.; Castermans, K.; Vire, E.; Dings, R.P.; Hoebers, N.T.; Mayo, K.H.; Oude Egbrink, M.G.; Molema, G.; Fuks, F.; van Engeland, M.; et al. Epigenetic regulation of tumor endothelial cell anergy: Silencing of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by histone modifications. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10770–10777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellebrekers, D.M.; Melotte, V.; Vire, E.; Langenkamp, E.; Molema, G.; Fuks, F.; Herman, J.G.; Van Criekinge, W.; Griffioen, A.W.; van Engeland, M. Identification of epigenetically silenced genes in tumor endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4138–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, M.J.; Nakajima, H.; Kim, K.W. Histone deacetylase inhibitor FK228 inhibits tumor angiogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 97, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Kurzrock, R.; Shankar, S. MS-275 sensitizes TRAIL-resistant breast cancer cells, inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis, and reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 3254–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camphausen, K.; Burgan, W.; Cerra, M.; Oswald, K.A.; Trepel, J.B.; Lee, M.J.; Tofilon, P.J. Enhanced radiation-induced cell killing and prolongation of gammaH2AX foci expression by the histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camphausen, K.; Cerna, D.; Scott, T.; Sproull, M.; Burgan, W.E.; Cerra, M.A.; Fine, H.; Tofilon, P.J. Enhancement of in vitro and in vivo tumor cell radiosensitivity by valproic acid. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 114, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, A.; Kurland, J.F.; Nishikawa, T.; Tanaka, T.; Hobbs, M.L.; Tucker, S.L.; Ismail, S.; Stevens, C.; Meyn, R.E. Histone deacetylase inhibitors radiosensitize human melanoma cells by suppressing DNA repair activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 4912–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, A.; Tanaka, T.; Hobbs, M.L.; Tucker, S.L.; Richon, V.M.; Meyn, R.E. Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, enhances the response of human tumor cells to ionizing radiation through prolongation of gamma-H2AX foci. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006, 5, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perona, M.; Thomasz, L.; Rossich, L.; Rodriguez, C.; Pisarev, M.A.; Rosemblit, C.; Cremaschi, G.A.; Dagrosa, M.A.; Juvenal, G.J. Radiosensitivity enhancement of human thyroid carcinoma cells by the inhibitors of histone deacetylase sodium butyrate and valproic acid. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 478, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Carr, T.; Dimtchev, A.; Zaer, N.; Dritschilo, A.; Jung, M. Attenuated DNA damage repair by trichostatin A through BRCA1 suppression. Radiat. Res. 2007, 168, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adimoolam, S.; Sirisawad, M.; Chen, J.; Thiemann, P.; Ford, J.M.; Buggy, J.J. HDAC inhibitor PCI-24781 decreases RAD51 expression and inhibits homologous recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19482–19487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachhap, S.K.; Rosmus, N.; Collis, S.J.; Kortenhorst, M.S.; Wissing, M.D.; Hedayati, M.; Shabbeer, S.; Mendonca, J.; Deangelis, J.; Marchionni, L.; et al. Downregulation of homologous recombination DNA repair genes by HDAC inhibition in prostate cancer is mediated through the E2F1 transcription factor. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koprinarova, M.; Botev, P.; Russev, G. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate enhances cellular radiosensitivity by inhibiting both DNA nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination. DNA Repair 2011, 10, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosato, R.R.; Almenara, J.A.; Grant, S. The histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 promotes differentiation or apoptosis in human leukemia cells through a process regulated by generation of reactive oxygen species and induction of p21CIP1/WAF1 1. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 3637–3645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruefli, A.A.; Bernhard, D.; Tainton, K.M.; Kofler, R.; Smyth, M.J.; Johnstone, R.W. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) overcomes multidrug resistance and induces cell death in P-glycoprotein-expressing cells. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 99, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, L.M.; Zhou, X.; Xu, W.S.; Scher, H.I.; Rifkind, R.A.; Marks, P.A.; Richon, V.M. The histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA arrests cancer cell growth, up-regulates thioredoxin-binding protein-2, and down-regulates thioredoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11700–11705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Jeong, E.G.; Choi, M.C.; Kim, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Song, S.H.; Park, J.; Bang, Y.J.; Kim, T.Y. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 10 induces thioredoxin-interacting protein and causes accumulation of reactive oxygen species in SNU-620 human gastric cancer cells. Mol. Cells 2010, 30, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerstedt, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Nair, D.; Holmgren, A. In vivo redox state of human thioredoxin and redox shift by the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 2002–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calin, G.A.; Dumitru, C.D.; Shimizu, M.; Bichi, R.; Zupo, S.; Noch, E.; Aldler, H.; Rattan, S.; Keating, M.; Rai, K.; et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15524–15529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquela-Kerscher, A.; Slack, F.J. Oncomirs—micrornas with a role in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roush, S.; Slack, F.J. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.-Y.; Ye, H.; Han, B.-W.; Wang, W.-T.; Wei, P.-P.; He, B.; Li, X.-J.; Chen, Y.-Q. Genome-wide screen identified let-7c/miR-99a/miR-125b regulating tumor progression and stem-like properties in cholangiocarcinoma. Oncogene 2016, 35, 3376–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Gong, X. Let-7c Inhibits the Proliferation, Invasion, and Migration of Glioma Cells via Targeting E2F5. Oncol. Res. 2018, 26, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Han, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Fang, F.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, N.; et al. MicroRNA let-7c inhibits migration and invasion of human non-small cell lung cancer by targeting ITGB3 and MAP4K3. Cancer Lett. 2014, 342, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, K.R.M.; Sousa-Canavez, J.M.; Reis, S.T.; Tomiyama, A.H.; Camara-Lopes, L.H.; Sañudo, A.; Antunes, A.A.; Srougi, M. Change in expression of miR-let7c, miR-100, and miR-218 from high grade localized prostate cancer to metastasis. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2011, 29, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, S.; Ichikawa, D.; Takeshita, H.; Morimura, R.; Hirajima, S.; Tsujiura, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Miyamae, M.; Nagata, H.; Konishi, H.; et al. Circulating miR-18a: A Sensitive Cancer Screening Biomarker in Human Cancer. In Vivo 2014, 28, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Shi, K.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, G.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, W. Effect of exosomal miRNA on cancer biology and clinical applications. Mol Cancer 2018, 17, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ma, M.; Dai, J.; Cui, C.; Si, L.; Sheng, X.; Chi, Z.; Xu, L.; Yu, S.; Xu, T.; et al. miR-let-7b and miR-let-7c suppress tumourigenesis of human mucosal melanoma and enhance the sensitivity to chemotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.M.; Grosshans, H.; Shingara, J.; Byrom, M.; Jarvis, R.; Cheng, A.; Labourier, E.; Reinert, K.L.; Brown, D.; Slack, F.J. RAS Is Regulated by the let-7 MicroRNA Family. Cell 2005, 120, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.-J.; Feng, Y.-C.; He, R.-Z.; Li, X.; Yu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, M.; Zhu, F.; et al. Let-7c inhibits cholangiocarcinoma growth but promotes tumor cell invasion and growth at extrahepatic sites. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.-Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Song, H.-Z.; Feng, B.; Huang, G.-C.; Wang, R.; Chen, L.-B.; De, W. Let-7c Governs the Acquisition of Chemo- or Radioresistance and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Phenotypes in Docetaxel-Resistant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, Q.; Ban, Z.; Cao, J.; Chu, T.; Lei, D.; Liu, C.; Guo, W.; Zeng, X. Effects of let-7c on the proliferation of ovarian carcinoma cells by targeted regulation of CDC25a gene expression. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 5543–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Wu, L.; Yao, J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wu, F. MicroRNA let-7c Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Induces Cell Cycle Arrest by Targeting CDC25A in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.-B.; Gu, J.; Zuo, H.-J.; Chen, Z.-G.; Zhao, W.; Li, M.; Ji, D.-B.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-Q. Let-7c functions as a metastasis suppressor by targeting MMP11 and PBX3 in colorectal cancer. J. Pathol. 2012, 226, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, D.; Sharifi, M. Antiproliferative effect of upregulation of hsa-let-7c-5p in human acute erythroleukemia cells. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Fu, X.; Mao, X.; Mao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Ding, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Let-7c-5p inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis by targeting ERCC6 in breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederichs, S.; Haber, D.A. Sequence Variations of MicroRNAs in Human Cancer: Alterations in Predicted Secondary Structure Do Not Affect Processing. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 6097–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.K.; Mattie, M.D.; Berger, C.E.; Benz, S.C.; Benz, C.C. Rapid alteration of microRNA levels by histone deacetylase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Lee, E.-M.; Cha, H.J.; Bae, S.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, S.-M.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; et al. MicroRNAs that respond to histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA and p53 in HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 35, 1343–1352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Fazio, P.; Montalbano, R.; Neureiter, D.; Alinger, B.; Schmidt, A.; Merkel, A.L.; Quint, K.; Ocker, M. Downregulation of HMGA2 by the pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat is dependent on hsa-let-7b expression in liver cancer cell lines. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C.; Naegeli, K.; Nam, S.; Ballard, B.; Hyslop, A.; Melki, C.; Reilly, E.; Hur, M.-W.; Nephew, K.P. A unique histone deacetylase inhibitor alters microRNA expression and signal transduction in chemoresistant ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012, 13, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pili, R.; Liu, G.; Chintala, S.; Verheul, H.; Rehman, S.; Attwood, K.; Lodge, M.A.; Wahl, R.; Martin, J.I.; Miles, K.M.; et al. Combination of the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat with bevacizumab in patients with clear-cell renal cell carcinoma: A multicentre, single-arm phase I/II clinical trial. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Shin, S.; Cha, H.J.; Yoon, Y.; Bae, S.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.J.; Park, I.C.; Jin, Y.W.; et al. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) changes microRNA expression profiles in A549 human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 24, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borbone, E.; De Rosa, M.; Siciliano, D.; Altucci, L.; Croce, C.M.; Fusco, A. Up-regulation of miR-146b and down-regulation of miR-200b contribute to the cytotoxic effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on ras-transformed thyroid cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E1031–E1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, B.; Yang, C. The microRNA-200 family: Small molecules with novel roles in cancer development, progression and therapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 6472–6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eades, G.; Yang, M.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q. miR-200a regulates Nrf2 activation by targeting Keap1 mRNA in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 40725–40733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Liang, Z.; Feng, A.; Salgado, E.; Shim, H. HDAC inhibitor suppresses proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells through regulation of miR-200c targeting CRKL. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 147, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-H.; Dimri, M.; Dimri, G.P. MicroRNA-31 Is a Transcriptional Target of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors and a Regulator of Cellular Senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 10555–10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalls, D.; Tang, S.-N.; Rodova, M.; Srivastava, R.K.; Shankar, S. Targeting epigenetic regulation of miR-34a for treatment of pancreatic cancer by inhibition of pancreatic cancer stem cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, D.; Liu, C.; Vasan, K.; Sulda, M.; Puduvalli, V.K.; Wierda, W.G.; Keating, M.J. Histone deacetylases mediate the silencing of miR-15a, miR-16, and miR-29b in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2012, 119, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibino, S.; Saito, Y.; Muramatsu, T.; Otani, A.; Kasai, Y.; Kimura, M.; Saito, H. Inhibitors of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) activate tumor-suppressor microRNAs in human cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2014, 3, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretzner, L.; Scuto, A.; Dino, P.M.; Kowolik, C.M.; Wu, J.; Ventura, P.; Jove, R.; Forman, S.J.; Yen, Y.; Kirschbaum, M.H. Combining histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat with aurora kinase inhibitors enhances lymphoma cell killing with repression of c-Myc, hTERT, and microRNA levels. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3912–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepore, I.; Dell’Aversana, C.; Pilyugin, M.; Conte, M.; Nebbioso, A.; De Bellis, F.; Tambaro, F.P.; Izzo, T.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Ferrara, F.; et al. HDAC inhibitors repress BARD1 isoform expression in acute myeloid leukemia cells via activation of miR-19a and/or b. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbert, D.R.; Wappel, R.L.; Moran, D.M.; Shell, S.A.; Bacus, S.S. The Role of Myc and the miR-17~92 Cluster in Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Induced Apoptosis of Solid Tumors. J. Cancer Ther. 2013, 4, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, H.; Lan, P.; Hou, Z.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, C. Histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA epigenetically regulates miR-17-92 cluster and MCM7 to upregulate MICA expression in hepatoma. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K.J.; Cobiac, L.; Le Leu, R.K.; Van der Hoek, M.B.; Michael, M.Z. Histone deacetylase inhibition in colorectal cancer cells reveals competing roles for members of the oncogenic miR-17-92 cluster. Mol. Carcinog. 2013, 52, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffgen, M.; Schmidt, D.H.; von Rücker, A.; Müller, S.C.; Ellinger, J. Epigenetic regulation of microRNA expression in renal cell carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 436, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamodu, O.A.; Kuo, K.-T.; Yuan, L.-P.; Cheng, W.-H.; Lee, W.-H.; Ho, Y.-S.; Chao, T.-Y.; Yeh, C.-T. HDAC inhibitor suppresses proliferation and tumorigenicity of drug-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells through regulation of hsa-miR-196a targeting BCR/ABL1. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 370, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, T.-H.; Ewald, B.; Zecevic, A.; Liu, C.; Sulda, M.; Papaioannou, D.; Garzon, R.; Blachly, J.S.; Plunkett, W.; Sampath, D. HDAC Inhibition Induces MicroRNA-182, which Targets RAD51 and Impairs HR Repair to Sensitize Cells to Sapacitabine in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3537–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seol, H.S.; Akiyama, Y.; Shimada, S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, T.I.; Chun, S.M.; Singh, S.R.; Jang, S.J. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-373 to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer through IRAK2 and LAMP1 axes. Cancer Lett. 2014, 353, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suraweera, A.; O’Byrne, K.J.; Richard, D.J. Combination Therapy with Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors (HDACi) for the Treatment of Cancer: Achieving the Full Therapeutic Potential of HDACi. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Xu, H.; Jin, W.; Wu, J.; Gao, S. Histone deacetylases inhibitor trichostatin A increases the expression of Dleu2/miR-15a/16-1 via HDAC3 in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 383, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.M.; Hiebert, S.W.; Eischen, C.M. Myc Induces miRNA-Mediated Apoptosis in Response to HDAC Inhibition in Hematologic Malignancies. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Dong, T.S.; Dalal, S.R.; Wu, F.; Bissonnette, M.; Kwon, J.H.; Chang, E.B. The Microbe-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate Targets miRNA-Dependent p21 Gene Expression in Human Colon Cancer. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray-Stewart, T.; Hanigan, C.L.; Woster, P.M.; Marton, L.J.; Casero, R.A. Histone Deacetylase Inhibition Overcomes Drug Resistance through a miRNA-Dependent Mechanism. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 2088–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Wang, W.-H.; Wu, W.-Y.; Hsu, C.-C.; Wei, L.-R.; Wang, S.-F.; Hsu, Y.-W.; Liaw, C.-C.; Tsai, W.-C. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitor AR-42 exhibits antitumor activity in pancreatic cancer cells by affecting multiple biochemical pathways. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Zhou, S.; Guo, B. Class I HDAC inhibitor mocetinostat induces apoptosis by activation of miR-31 expression and suppression of E2F6. Cell Death Discov. 2016, 2, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Katsushima, K.; Shinjo, K.; Hatanaka, A.; Ohka, F.; Suzuki, S.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Soga, N.; Takahashi, S.; Kondo, Y. Histone Deacetylase Inhibition in Prostate Cancer Triggers miR-320–Mediated Suppression of the Androgen Receptor. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4192–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins-Burow, B. The histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A alters microRNA expression profiles in apoptosis-resistant breast cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 27, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-F.; Long, C.-Y.; Wu, C.-H.; Wu, D.-C.; Lee, J.-N.; Chang, W.-C.; Tsai, E.-M. HDAC Inhibitors Target HDAC5, Upregulate MicroRNA-125a-5p, and Induce Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, D.E.; Park, S.B.; Kim, K.; Kim, C.; Song, S.Y. CG200745, an HDAC inhibitor, induces anti-tumour effects in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines via miRNAs targeting the Hippo pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandres, E.; Agirre, X.; Bitarte, N.; Ramirez, N.; Zarate, R.; Roman-Gomez, J.; Prosper, F.; Garcia-Foncillas, J. Epigenetic regulation of microRNA expression in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 2737–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas, J.; Ni, X.; Castanares, M.; Liu, M.M.; Esopi, D.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Rodriguez, R.; Mendell, J.T.; Lupold, S.E. A novel source for miR-21 expression through the alternative polyadenylation of VMP1 gene transcripts. Nucl. Acids Res. 2012, 40, 6821–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, Y.; Nakada, C.; Noguchi, T.; Tanigawa, M.; Nguyen, L.T.; Uchida, T.; Hijiya, N.; Matsuura, K.; Fujioka, T.; Seto, M.; et al. MicroRNA-375 is downregulated in gastric carcinomas and regulates cell survival by targeting PDK1 and 14-3-3zeta. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buurman, R.; Gürlevik, E.; Schäffer, V.; Eilers, M.; Sandbothe, M.; Kreipe, H.; Wilkens, L.; Schlegelberger, B.; Kühnel, F.; Skawran, B. Histone deacetylases activate hepatocyte growth factor signaling by repressing microRNA-449 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 811–820.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Zeng, L.; Jiang, X. microRNA-889 is downregulated by histone deacetylase inhibitors and confers resistance to natural killer cytotoxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trécul, A.; Morceau, F.; Gaigneaux, A.; Schnekenburger, M.; Dicato, M.; Diederich, M. Valproic acid regulates erythro-megakaryocytic differentiation through the modulation of transcription factors and microRNA regulatory micro-networks. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 92, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, J.; DeBlasio, D.; Govindarajan, S.S.; Zhang, S.; Perera, R.J. Epigenetic regulation of microRNA-375 and its role in melanoma development in humans. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 2467–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canella, A.; Nieves, H.C.; Sborov, D.W.; Cascione, L.; Radomska, H.S.; Smith, E.; Stiff, A.; Consiglio, J.; Caserta, E.; Rizzotto, L.; et al. HDAC inhibitor AR-42 decreases CD44 expression and sensitizes myeloma cells to lenalidomide. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 31134–31150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.M.; Benarroch, Y.; Chan, E.K.L. Anti-Cancer Drugs Reactivate Tumor Suppressor miR-375 Expression in Tongue Cancer Cells: miR-375 REACTIVATION BY ANTI-CANCER DRUGS. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Liang, G.; Egger, G.; Friedman, J.M.; Chuang, J.C.; Coetzee, G.A.; Jones, P.A. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, K.V.; Martínez de Paz, A.; Tyagi, M.; Cheema, M.S.; Thambirajah, A.A.; Gretzinger, T.L.; Stefanelli, G.; Chow, R.L.; Krupke, O.; Hendzel, M.; et al. Trichostatin A decreases the levels of MeCP2 expression and phosphorylation and increases its chromatin binding affinity. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meidhof, S.; Brabletz, S.; Lehmann, W.; Preca, B.-T.; Mock, K.; Ruh, M.; Schüler, J.; Berthold, M.; Weber, A.; Burk, U.; et al. ZEB1-associated drug resistance in cancer cells is reversed by the class I HDAC inhibitor mocetinostat. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Lin, H.; Luo, X.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z. miR-605 joins p53 network to form a p53: miR-605: Mdm2 positive feedback loop in response to stress. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-J.; Yang, H.-Q.; Xia, W.; Cui, L.; Xu, R.-F.; Lu, H.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, B.; Tian, Z.-N.; Cao, Y.-J.; et al. Down-regulation of miR-605 promotes the proliferation and invasion of prostate cancer cells by up-regulating EN2. Life Sci. 2017, 190, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, H.; Hashemi, M.; Bizhani, F.; Hashemi, S.M.; Bahari, G. Association study of miR-100, miR-124-1, miR-218-2, miR-301b, miR-605, and miR-4293 polymorphisms and the risk of breast cancer in a sample of Iranian population. Gene 2018, 647, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najminejad, H.; Kalantar, S.M.; Abdollahpour-Alitappeh, M.; Karimi, M.H.; Seifalian, A.M.; Gholipourmalekabadi, M.; Sheikhha, M.H. Emerging roles of exosomal miRNAs in breast cancer drug resistance. IUBMB Life 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardini, B.; Sabo, A.A.; Birolo, G.; Calin, G.A. Noncoding RNAs in Extracellular Fluids as Cancer Biomarkers: The New Frontier of Liquid Biopsies. Available online: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.gate2.inist.fr/pubmed/31416190 (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Thery, C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D. Exosomal miRNA Cargo as Mediator of Immune Escape Mechanisms in Neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 1293–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanakis, N.-I.; Baloche, V.; Busson, P. Tumor exosomal microRNAs thwarting anti-tumor immune responses in nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Ann. Trans. Med. 2017, 5, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, B.; Kirave, P.; Gondaliya, P.; Jash, K.; Jain, A.; Tekade, R.K.; Kalia, K. Exosomal miRNA in chemoresistance, immune evasion, metastasis and progression of cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, D.-H.; Hong, J.-Y.; Park, H.J.; Lee, S.K. The role of exosomes and miRNAs in drug-resistance of cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Class | Targeted Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) | Localization | Zn2+ | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1, 2, 3, 8 | Nucleus | Yes | Ubiquitous |

| IIa | 4, 5, 7, 9 | Nucleus and cytoplasm | Yes | Tissue specific |

| IIb | 6, 10 | Cytoplasm | Yes | Tissue specific |

| III | Sirtuins 1–7 | Nucleus, cytoplasm and mitochondria | No | Variable |

| IV | 11 | Nucleus and cytoplasm | Yes | Ubiquitous |

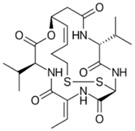

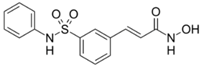

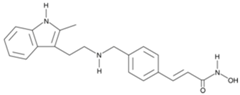

| Name | Structure | Year of Approval | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vorinostat |  | 2006 | Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma |

| Romidepsin |  | 2009 2011 | Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma Peripheral T Cell Lymphoma |

| Belinostat |  | 2014 | Peripheral T Cell Lymphoma |

| Panobinostat |  | 2015 | Multiple Myeloma |

| Disease | Targets | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glioma | E2F5 | Control of cell cycle | [86] |

| Melanoma | CALU | Protein folding and sorting | [91] |

| Lung cancer | RAS | Oncogene | [92] |

| NSCLC | ITGB3/MAP4K3 | Metastatic abilities | [87] |

| Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) | IL6-R | Immune response | [85] |

| EZH2/DVL3/βcatenin | Metastatic abilities | [93] | |

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | IL8 | Immune response | [93] |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | BCL-XL | Inhibitor of cell death | [94] |

| Ovarian carcinoma | CDC25A | Control of cell cycle | [95] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | CDC25A | Control of cell cycle | [96] |

| Colorectal cancer | MMP11/PBX3 | Metastatic abilities | [97] |

| Erythroleukemia | PBX2 | Transcription | [98] |

| Breast cancer | ERCC6 | Transcription/excision repair | [99] |

| Cancers | HDACi | miRNAs | miRNA Targets | Pathways | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | Vorinostat |  miR-200a miR-200a |  Keap1 Keap1 |  Nrf2 antioxidant pathway Nrf2 antioxidant pathway | [109] |

miR-200C miR-200C |  CRKL CRKL |  Invasion Invasion | [110] | ||

Migration Migration | |||||

| Panobinostat |  miR-31, miR-125a, miR-125b, miR-205, miR-141, miR-200c miR-31, miR-125a, miR-125b, miR-205, miR-141, miR-200c |  NF-kB inducing kinase, ITGA5, SEPHS1, RSBN1, TFDP1 NF-kB inducing kinase, ITGA5, SEPHS1, RSBN1, TFDP1 |  Cellular senescence Cellular senescence | [111] | |

BMI1 and EZH2 (indirect) BMI1 and EZH2 (indirect) | |||||

| Colorectal | Vorinostat | Changes in 275 out of the 723 studied human miRNAs | see article for predicted targets | [102] | |

miR-17-92 cluster miR-17-92 cluster |  PTEN PTEN | Proliferation (opposite effects depending on members of the cluster) | [119] | ||

mRNA levels of c-MYC, E2F1, E2F2 and E2F3 mRNA levels of c-MYC, E2F1, E2F2 and E2F3 | |||||

| HCC | Vorinostat Panobinostat |  let-7b let-7b |  p21 p21 |  E2F1 transcriptional activity E2F1 transcriptional activity | [103] |

MYC, MET, HMGA2, TRAIL, BCLX MYC, MET, HMGA2, TRAIL, BCLX |  Cell proliferation Cell proliferation | ||||

| Vorinostat |  miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-20a, miR-93, miR-106b miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-20a, miR-93, miR-106b |  MICA, MICB MICA, MICB |  Recognition of tumor by innate immune cells Recognition of tumor by innate immune cells | [118] | |

| Leukemia | Vorinostat Romidepsin |  miR-15a, miR16, miR29b miR-15a, miR16, miR29b |  MCL1, BCL-2 MCL1, BCL-2 |  Apoptosis Apoptosis | [113] |

| Vorinostat |  23 miR (e.g. miR-19a, miR-19b) 23 miR (e.g. miR-19a, miR-19b) |  BARD-1 BARD-1 |  Sensitivity to vorinostat Sensitivity to vorinostat | [116] | |

26 miR (see article) 26 miR (see article) |  Apoptosis Apoptosis | ||||

miR-196a miR-196a |  BCR/ABL BCR/ABL |  Transcriptional activity of the pluripotency factors Transcriptional activity of the pluripotency factors | [121] | ||

Cell cycle progression genes Cell cycle progression genes | |||||

Sentivity to imatinib mesylate (a Tyrosine Kinase inhibitor) Sentivity to imatinib mesylate (a Tyrosine Kinase inhibitor) | |||||

| Panobinostat | miR-26a, miR-133a, miR-181b, miR-182, miR-200c, miR-211, miR-320a, miR-320c, miR-423-5p, miR-638, miR-877, miR-1307, miR-1308, miR-1268 miR-516a-3p, miR-605 |  Homologous recombination repair pathway (RAD51, BRCA1, NBS1) Homologous recombination repair pathway (RAD51, BRCA1, NBS1) |  Homologous recombination repairdelay DNA repair Homologous recombination repairdelay DNA repair Sensitivity to CNDAC (prodrug used in AML) Sensitivity to CNDAC (prodrug used in AML) | [122] | |

| Lung | Vorinostat |  let7b, miR-17*, miR-92a let7b, miR-17*, miR-92a | expected targets for each miR listed in the article | [106] | |

miR-373 miR-373 |  LAMP1, VSP4B, IRAK2, BRMS1L, SYDE1, CYBRD1, PDIK1L, C10orf46, TGFBR2 LAMP1, VSP4B, IRAK2, BRMS1L, SYDE1, CYBRD1, PDIK1L, C10orf46, TGFBR2 | Associated with poorer disease-free survival | [123] | ||

| Lymphoma | Vorinostat |  miR-15b, miR-17-3p, miR-17-5p, miR-18, miR-34a, miR-155 miR-15b, miR-17-3p, miR-17-5p, miR-18, miR-34a, miR-155 |  c-myc c-myc |  Sensitivity to apoptosis Sensitivity to apoptosis | [115] |

| Ovarian | Vorinostat |  Let-7, miR-99, miR-100, miR-125… (see figure in article) Let-7, miR-99, miR-100, miR-125… (see figure in article) | [104] | ||

| Pancreatic | Vorinostat |  miR-34a miR-34a |  Cyclin D1, CDK6, SIRT1, survivin, BCL-2, VEGF, Notch pathway Cyclin D1, CDK6, SIRT1, survivin, BCL-2, VEGF, Notch pathway |  Cell proliferation, stem cell renewal, invasivness Cell proliferation, stem cell renewal, invasivness | [112] |

p21/CIP1, acetylated p53, PUMA p21/CIP1, acetylated p53, PUMA |  Apoptosis, cell cycle arrest Apoptosis, cell cycle arrest | ||||

) or increase (

) or increase ( ) of either miRNA or target and their associated pathway.

) of either miRNA or target and their associated pathway.| Cancers | HDACi | miRNAs | miRNA Targets | Pathways | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | LAQ824 |  miR27a (≈40% of miRNAs modulated) miR27a (≈40% of miRNAs modulated) |  RYBP/DEDAF, ZBTB10/RINZF RYBP/DEDAF, ZBTB10/RINZF | [101] | |

| TSA |  22 miR among which: miR-1, miR-143, miR-144, miR-191-3p, miR-202-5p… 22 miR among which: miR-1, miR-143, miR-144, miR-191-3p, miR-202-5p… | (predicted targets for each miRNAs provided in the article) | [132] | ||

10 miR among which: miR-500, miR-645, miR-512-3p, miR-613… 10 miR among which: miR-500, miR-645, miR-512-3p, miR-613… | |||||

| (see article for complete listing) | |||||

| TSA, VPA NaBu… |  miR125-a miR125-a |  HDAC5 mRNA HDAC5 mRNA |  apoptosis apoptosis | [133] | |

| CCA | CG200746 |  miR-22-3p, miR-22-5p, miR-194-3p, miR-194-5p, miR-210-3p, miR-509-3p miR-22-3p, miR-22-5p, miR-194-3p, miR-194-5p, miR-210-3p, miR-509-3p | expression induced in treated cells |  tumor growth tumor growth proliferation proliferation | [134] |

| Colorectal | PBA |  miR-9, miR-127, miR-129, miR-137 miR-9, miR-127, miR-129, miR-137 | [135] | ||

| Butyrate |  18 miRNAs 18 miRNAs |  p21 protein expression p21 protein expression |  proliferation proliferation | [127] | |

26 miRNAs (among which miR-17-92a, miR-18b-106 and miR25-106b clusters) 26 miRNAs (among which miR-17-92a, miR-18b-106 and miR25-106b clusters) | |||||

| Entinostat (MS-275) |  pri and mature miR-21 pri and mature miR-21 | [136] | |||

| Gastric carcinoma | TSA |  miR-375 miR-375 |  PDK1, XIAP, 14-3-3ζ (YWHAZ), cIAP-2 (BIRC3) PDK1, XIAP, 14-3-3ζ (YWHAZ), cIAP-2 (BIRC3) |  Tumor cell viability Tumor cell viability | [137] |

| BCL2L11 (Bim) |  apoptosis apoptosis | ||||

| HCC | TSA |  miR-449 miR-449 |  c-MET c-MET |  cell proliferation cell proliferation apoptosis apoptosis | [138] |

| Sodium valproate |  miR-889 miR-889 |  MICB MICB |  sensitivity to NK cell-mediated lysis sensitivity to NK cell-mediated lysis | [139] | |

| Leukemia | valpromide (=VPA analog) |  miR-144, miR-451, miR-155 (all cells) miR-144, miR-451, miR-155 (all cells) |  GATA-1 GATA-1 |  erythropoiesis impairment erythropoiesis impairment | [140] |

GATA-2 GATA-2 | |||||

miR-15a, miR-16, miR-222 (some cells) miR-15a, miR-16, miR-222 (some cells) |  ETS family (PU.1, ETS-1, GABP-α, Fli-1) ETS family (PU.1, ETS-1, GABP-α, Fli-1) |  megakaryocyte features megakaryocyte features | |||

| Lung | Entinostat (MS275) |  miR-200a miR-200a |  KEAP1/NRF2 KEAP1/NRF2 |  cell growth cell growth | [128] |

| TSA |  Let-7, miR-15a, miR-16-1 Let-7, miR-15a, miR-16-1 |   proliferation and apoptosis proliferation and apoptosis | [125] | ||

| induce cell cycle arrest | |||||

| Lymphoma | RGFP966 |  miR-15a, miR-195, let-7a (in vitro and in vivo) miR-15a, miR-195, let-7a (in vitro and in vivo) |  BCL-2, BCL-XL BCL-2, BCL-XL |  apoptosis apoptosis | [126] |

| Melanoma | 4PBA (or 5Aza, 5Aza + 4PBS) |  miR-34b, miR-132, miR-142-3p, miR-200a, miR-375, miR-489 miR-34b, miR-132, miR-142-3p, miR-200a, miR-375, miR-489 |  Proliferation, invasion Proliferation, invasion | [141] | |

wound healing wound healing | |||||

| changes in cell morphology | |||||

| Multiple Myeloma | AR-42 |  miR-9-5p miR-9-5p |  CD44 CD44 | [142] | |

| Ovarian | AR42 |  miR-15a, miR-34, … miR-15a, miR-34, …(see figure in article) |  WT1, PAX2, GATA6, APO2/TRAIL… WT1, PAX2, GATA6, APO2/TRAIL…(see article) |  EMT, Canonical Wnt R signaling EMT, Canonical Wnt R signaling Negative regulation of cell cycle processes, extrinsic apoptosis Negative regulation of cell cycle processes, extrinsic apoptosis | [104] |

| Pancreatic | AR-42 |  miR-30d, miR-33, miR-125b miR-30d, miR-33, miR-125b |  p53, cyclin B2, CDC25B p53, cyclin B2, CDC25B |  Invasion, tumor growth Invasion, tumor growth | [129] |

| Prostate | Mocetinostat |  miR-31 miR-31 |  E2F6 E2F6 |  apoptosis apoptosis | [130] |

| OBP-801 |  miR-320a in vitro and in vivo (rat) miR-320a in vitro and in vivo (rat) |  PSA, androgen receptor PSA, androgen receptor |  Viability, cell growth, cell proliferation, prostate tumorigenesis (in vivo) Viability, cell growth, cell proliferation, prostate tumorigenesis (in vivo) | [131] | |

| Tongue | TSA (or Doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, etoposide treatments) |  miR-375 miR-375 |  CIP2A, MYC, 14-3-3z, E6AP, E6, E7 CIP2A, MYC, 14-3-3z, E6AP, E6, E7 |  cell proliferation, migration and invasion cell proliferation, migration and invasion | [143] |

p21, p53, RB p21, p53, RB | |||||

| Various models | PBA (and 5-Aza-CdR) |  17 miR/313 studied (see article for details) 17 miR/313 studied (see article for details) |  BCL6 (suggested) BCL6 (suggested) | [144] | |

| TSA |  miR132/212 miR132/212 |  MeCP2 MeCP2 | [145] | ||

) or increase (

) or increase ( ) of either miRNA or target and their associated pathway.

) of either miRNA or target and their associated pathway.© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Autin, P.; Blanquart, C.; Fradin, D. Epigenetic Drugs for Cancer and microRNAs: A Focus on Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Cancers 2019, 11, 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11101530

Autin P, Blanquart C, Fradin D. Epigenetic Drugs for Cancer and microRNAs: A Focus on Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Cancers. 2019; 11(10):1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11101530

Chicago/Turabian StyleAutin, Pierre, Christophe Blanquart, and Delphine Fradin. 2019. "Epigenetic Drugs for Cancer and microRNAs: A Focus on Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors" Cancers 11, no. 10: 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11101530

APA StyleAutin, P., Blanquart, C., & Fradin, D. (2019). Epigenetic Drugs for Cancer and microRNAs: A Focus on Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Cancers, 11(10), 1530. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11101530