A Hardware-Friendly Joint Denoising and Demosaicing System Based on Efficient FPGA Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- At the algorithm level, a hardware-inspired and multi-stage network structure (LJDD-Net) is proposed, which achieves excellent restoration quality with lower model complexity and tends to improve latency and efficiency. Compared with the standard convolutional solution, the parameters and MACs are reduced by 83.38% and 77.71%, respectively.

- Based on algorithm–hardware co-design, a unified and flexible mechanism is employed. The computing unit adopts a fully pipelined dataflow architecture with a scalable hardware interface, which effectively addresses resource constraints across different platforms. In addition, a padding mechanism based on address mapping is proposed to achieve zero resource overhead.

- The hardware architecture with multiple levels of parallelism, implemented on a Xilinx development board, achieves a 2.09× improvement in computational efficiency over the state-of-the-art method [27]. Compared with the two parallelization schemes, the proposed hardware accelerator achieves energy-efficiency improvements of 72.56× and 24.28× on the CPU platform, and 85.39× and 28.58× on the GPU platform, respectively. Moreover, the design demonstrates the advantages of high quality, low cost, and high performance, while maintaining a balanced trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency, as verified in subsequent experiments.

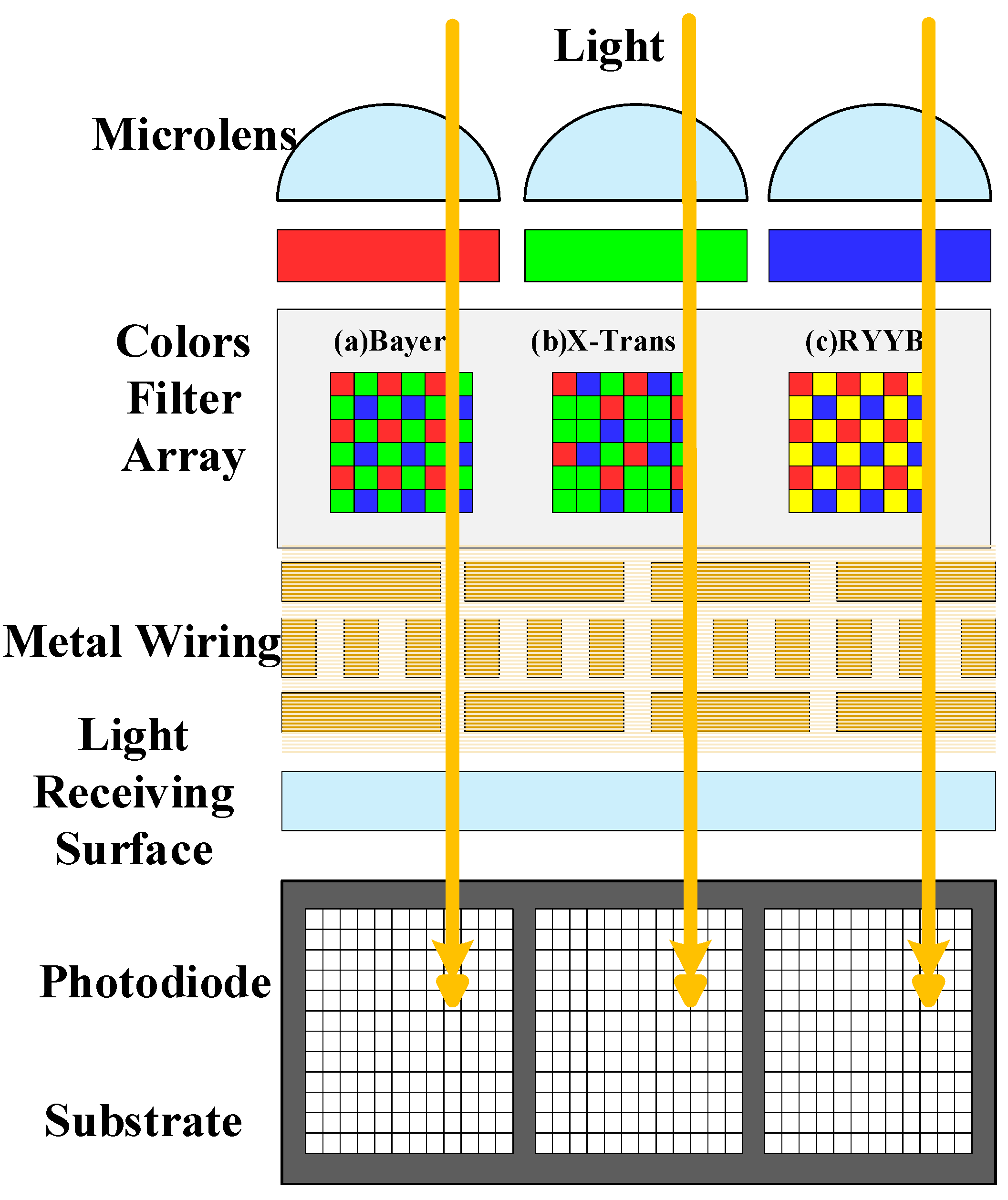

2. Related Work and Motivation

2.1. Multi-Stage Methods

2.2. Design Challenges in DM&DN Hardware Solutions

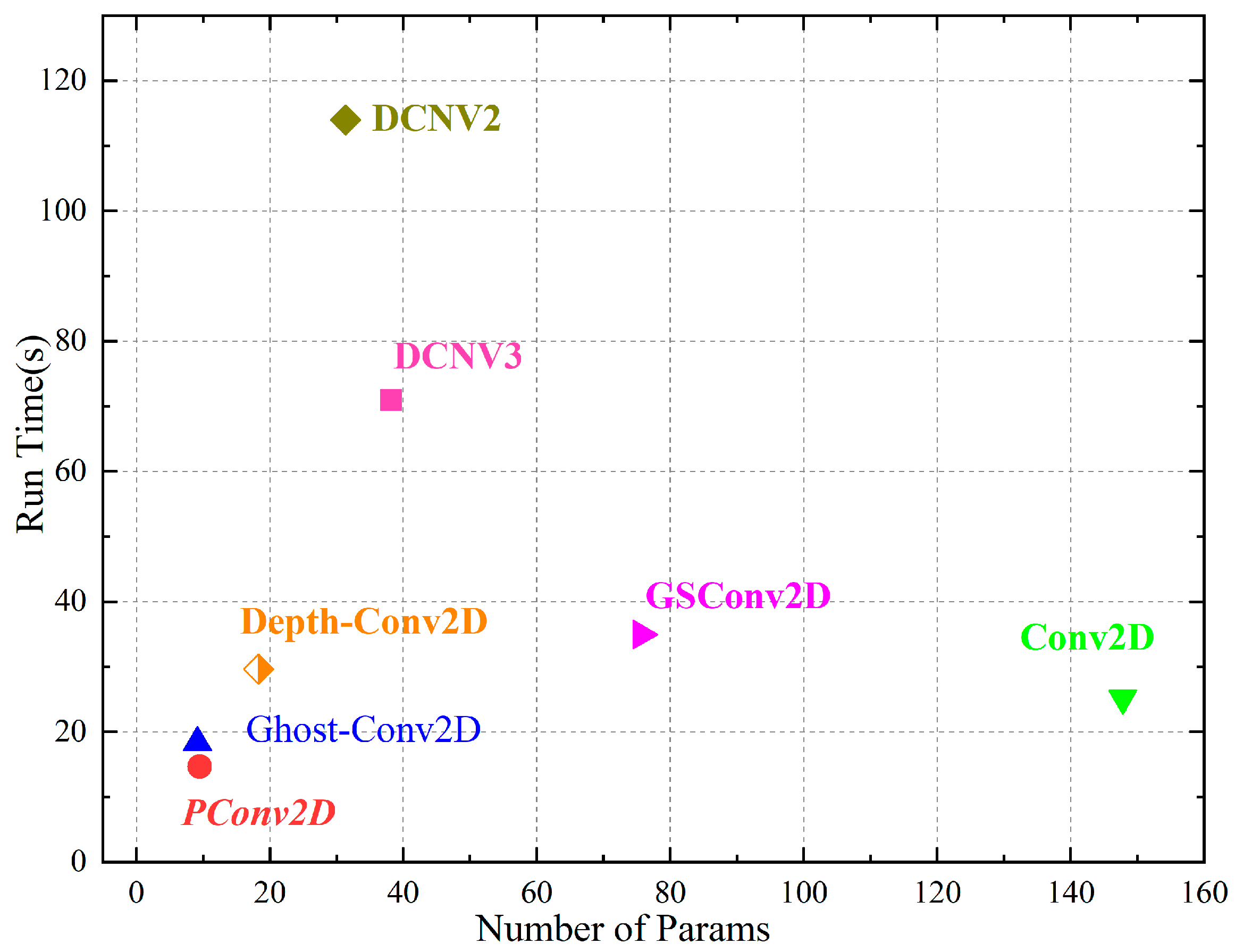

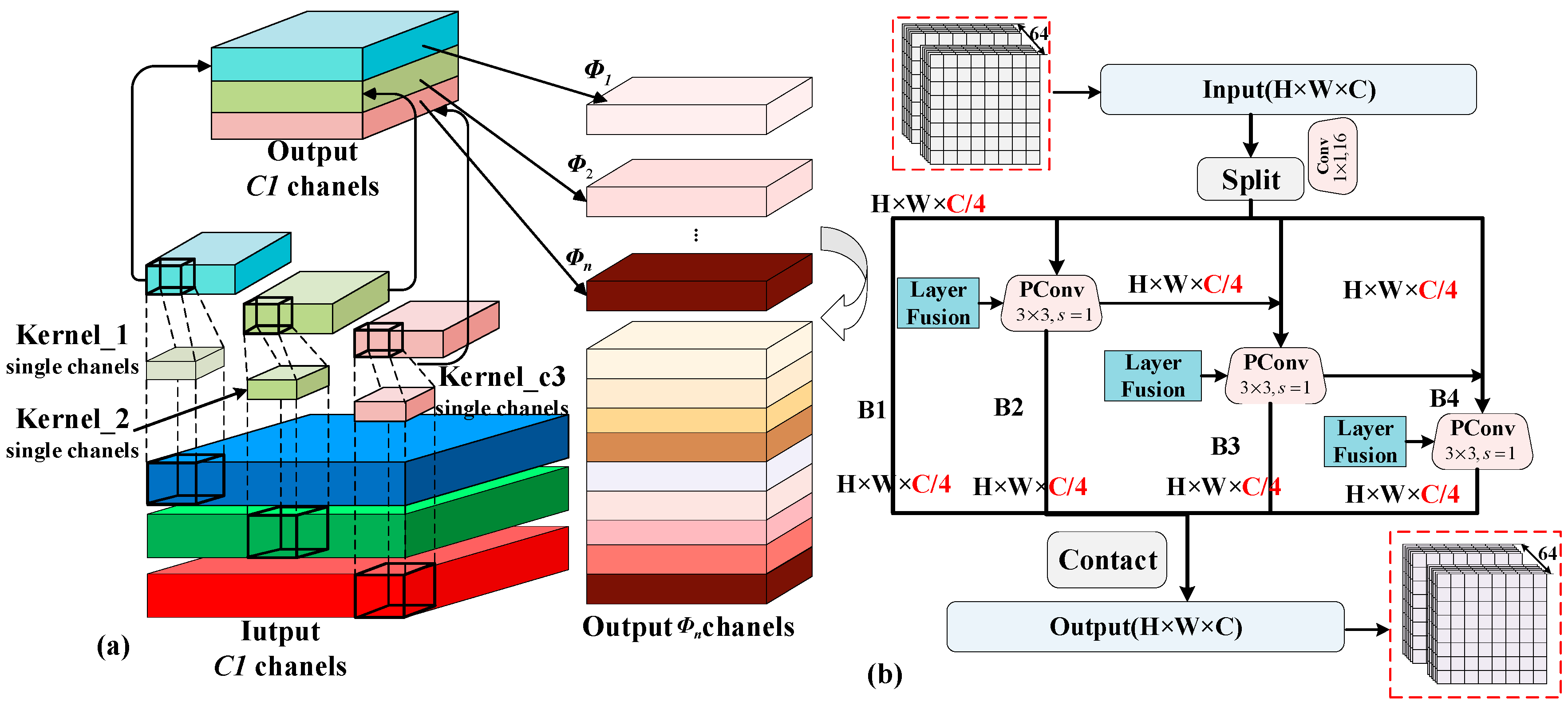

2.3. Exploring Various Convolution Operations

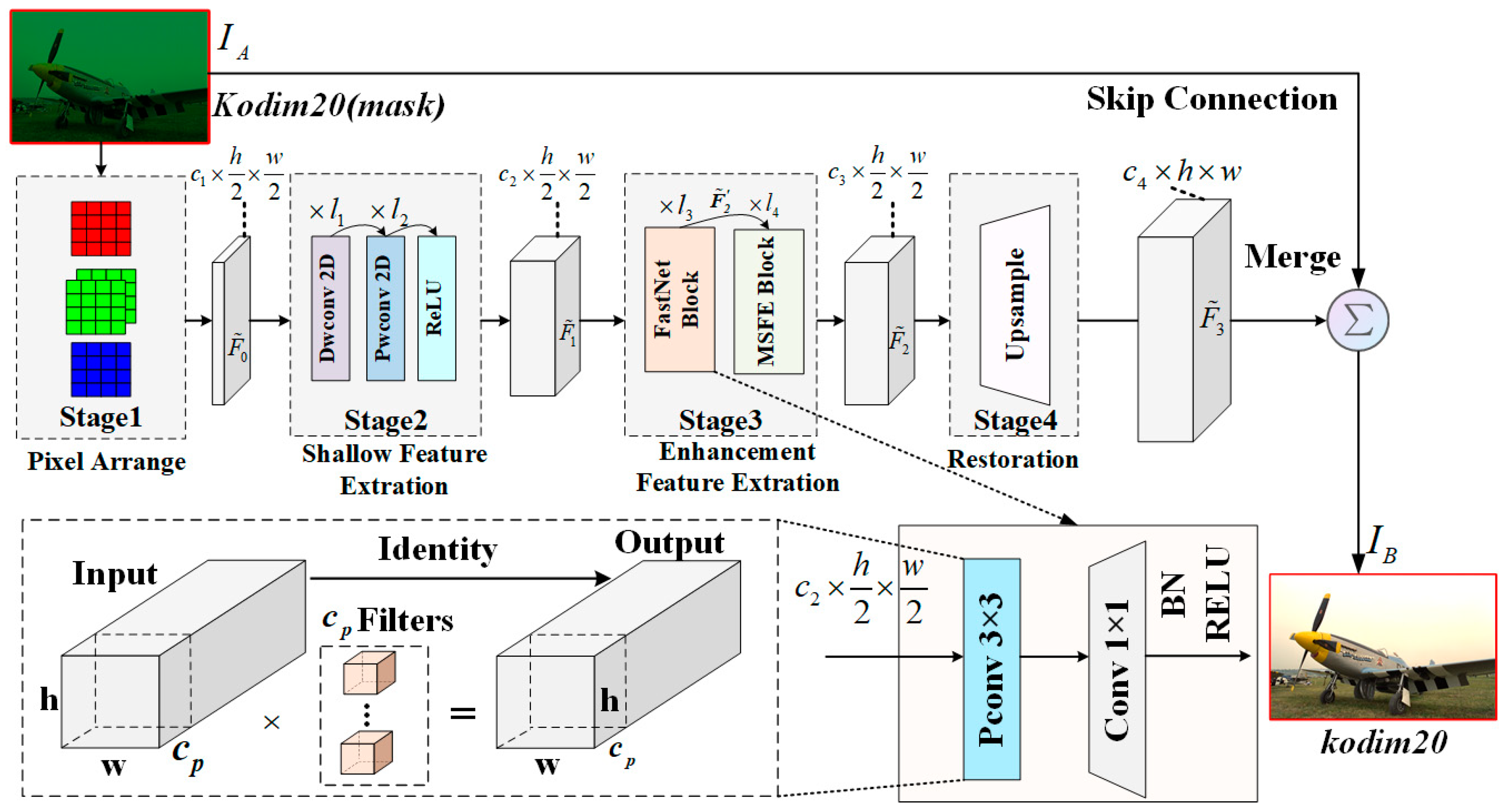

3. Network Design Incorporating Partial Convolution

3.1. Definition of RAW–sRGB Pairs

3.2. Proposed Method

3.3. Deep Feature Extraction and Restoration Layer

3.4. Parameters and Analysis

4. Hardware Implementation and Optimization Strategy

4.1. Data Flow and Module Implementation

4.2. Details of Convolution Calculation

- (1)

- Unified computing engine

- (2)

- Padding mechanism and construction matrix

- (3)

- Timing diagrams of different convolution modules

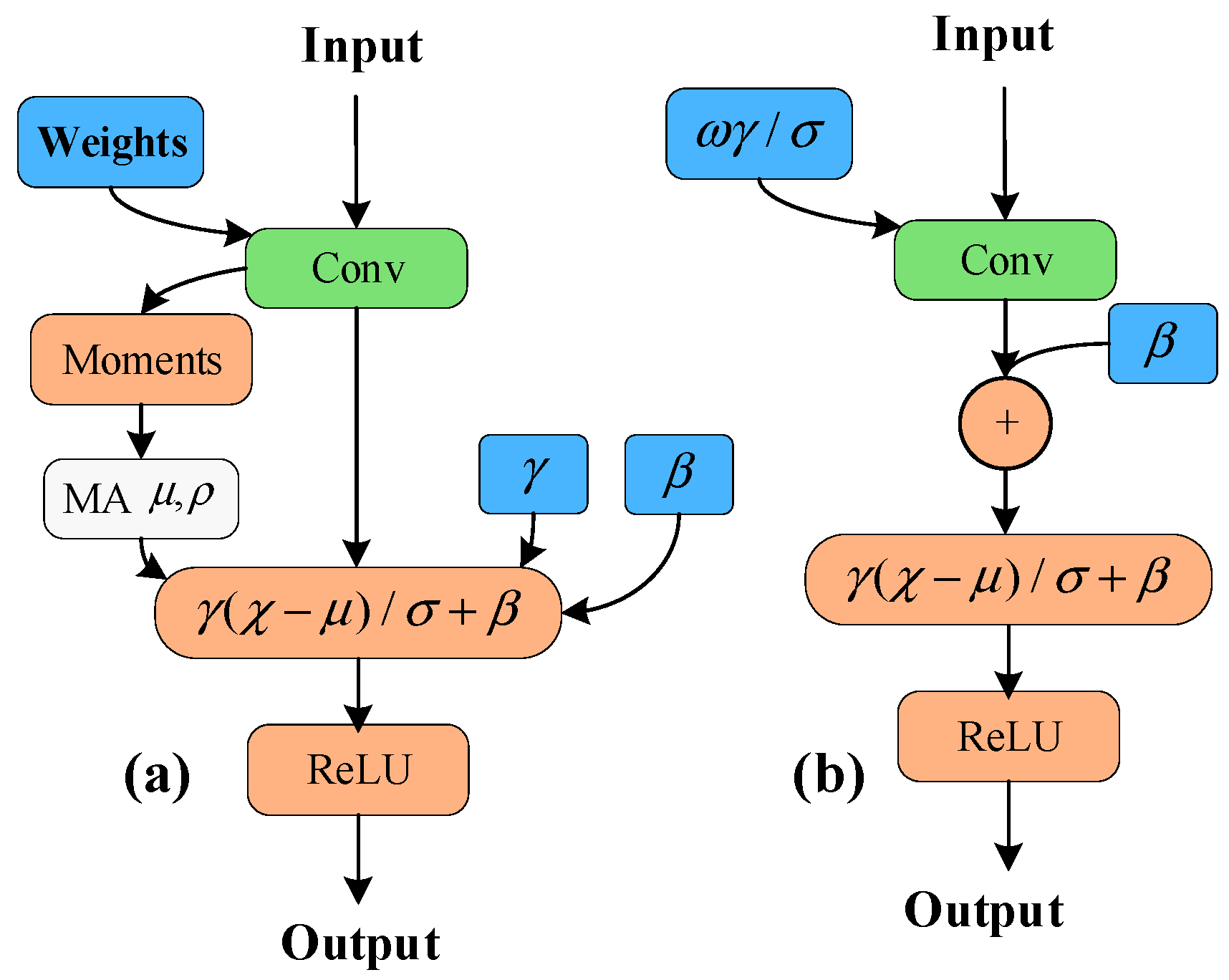

4.3. Layer Fusion and Quantization

5. Evaluation and Experimental Results

5.1. Preliminary

5.2. Training Strategy and Ablation Study

5.3. Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison

5.4. Hardware Implementation Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, H.; Tian, Q.; Farrell, J.; Wandell, B.A. Learning the Image Processing Pipeline. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 5032–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckler, M.; Jayasuriya, S.; Sampson, A. Reconfiguring the Imaging Pipeline for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 975–984. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, D.; Calvagno, G. Color Image Demosaicking: An Overview. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2011, 26, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 40429-2021; Information Technology—Requirements for Automotive-Grade Cameras. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=4754CB1B7AD798F288C52D916BFECA34 (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Yu, K.; Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Loy, C.C.; Gu, J. ReconfigISP: Reconfigurable Camera Image Processing Pipeline. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 4228–4237. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Gharbi, M.; Adams, A.; Kamil, S.; Li, T.-M.; Barnes, C.; Ragan-Kelley, J. Searching for Fast Demosaicking Algorithms. ACM Trans. Graph. 2022, 41, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, M.; Dou, R.; Yu, S.; Liu, L.; Wu, N. A Compact High-Quality Image Demosaicking Neural Network for Edge-Computing Devices. Sensors 2021, 21, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, A.; Timofte, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Peng, Z.; Ren, S.; et al. AIM 2020 Challenge on Learned Image Signal Processing Pipeline. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ehret, T.; Facciolo, G. A Study of Two CNN Demosaicking Algorithms. Image Process. Line 2019, 9, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Meyer, D.E.; Xu, H.; Kuester, F. Splatty- a Unified Image Demosaicing and Rectification Method. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 786–795. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, J.; Brunhaver, J.; DeVito, Z.; Ragan-Kelley, J.; Cohen, N.; Bell, S.; Vasilyev, A.; Horowitz, M.; Hanrahan, P. Darkroom: Compiling High-Level Image Processing Code into Hardware Pipelines. ACM Trans. Graph. 2014, 33, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, E.; Giryes, R.; Bronstein, A.M. DeepISP: Toward Learning an End-to-End Image Processing Pipeline. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 28, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, W.; Wang, Z. Deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: A comprehensive review. Neural Comput. 2017, 29, 2352–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, K.; Nash, R. An Introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.08458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, N.; Moolayil, J. Convolutional Neural Networks. In Deep Learning with Python: Learn Best Practices of Deep Learning Models with PyTorch; Ketkar, N., Moolayil, J., Eds.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 197–242. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kuen, J.; Ma, L.; Shahroudy, A.; Shuai, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Cai, J.; et al. Recent Advances in Convolutional Neural Networks. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Facciolo, G.; Morel, J.-M. A Review of an Old Dilemma: Demosaicking First, or Denoising First? In Proceedings of the the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 514–515. [Google Scholar]

- Din, S.; Paul, A.; Ahmad, A. Smart Embedded System Based on Demosaicking for Enhancement of Surveillance Systems. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 86, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhu, S.; Ma, Z.; Xiong, R.; Zeng, B. NTSDCN: New Three-Stage Deep Convolutional Image Demosaicking Network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 3725–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S. Real-Scene Reflection Removal with RAW-RGB Image Pairs. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 3759–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, M.V.; McDonagh, S.; Maggioni, M.; Leonardis, A.; Pérez-Pellitero, E. Model-Based Image Signal Processors via Learnable Dictionaries. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wu, F.F.; Dong, W.; Shi, G.; Li, X. Lightweight Deep Residue Learning for Joint Color Image Demosaicking and Denoising. In Proceedings of the 2018 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Beijing, China, 20–24 August 2018; pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Chollet, F. Depthwise separable convolutions for neural machine translation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Network decoupling: From regular to depthwise separable convolutions. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.05517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.-H.; Chan, S.-H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J.; Lai, R.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, L.; Yang, Y.; Gu, L. Memory-Efficient Deformable Convolution Based Joint Denoising and Demosaicing for UHD Images. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 7346–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, M.; Chaurasia, G.; Paris, S.; Durand, F. Deep Joint Demosaicking and Denoising. ACM Trans. Graph. 2016, 35, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadidos, A.O.; Khadidos, A.O.; Khan, F.Q.; Tsaramirsis, G.; Ahmad, A. Bayer Image Demosaicking and Denoising Based on Specialized Networks Using Deep Learning. Multimed. Syst. 2021, 27, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Jin, Z.; Steinbach, E. Color Image Demosaicking Using a 3-Stage Convolutional Neural Network Structure. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Athens, Greece, 7–10 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.P.P.; Peter, K.J.; Kingsly, C.S. De-Noising and Demosaicking of Bayer Image Using Deep Convolutional Attention Residual Learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 20323–20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jin, Q.; Facciolo, G.; Zeng, T.; Morel, J.-M. Joint Demosaicking and Denoising Benefits from a Two-Stage Training Strategy. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 434, 115330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasingam, S. Deep Camera: A Fully Convolutional Neural Network for Image Signal Processing; IEEE: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019; pp. 3868–3878. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.; Lee, H.; Je, H.; Kim, K.; Ryu, D.; No, A. PyNET-Q×Q: An Efficient PyNET Variant for Q×Q Bayer Pattern Demosaicing in CMOS Image Sensors. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 44895–44910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Cai, J.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, L. CameraNet: A Two-Stage Framework for Effective Camera ISP Learning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2248–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Ouyang, J. Channel-by-Channel Demosaicking Networks with Embedded Spectral Correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1906.09884. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, C.-Y.; Yang, F.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Fang, Y.-W. Efficient VLSI Architecture for Edge-Oriented Demosaicking. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018, 28, 2038–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Xiong, X.; Xu, D.; Zhu, X.; Fan, Y. A Hardware Friendly Demosaicking Algorithm Based on Edge Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 16th International Conference on Solid-State & Integrated Circuit Technology (ICSICT), Nanjing, China, 25–28 October 2022; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Li, D. Real time bayer raw video projective transformation system using FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Limassol, Cyprus, 6–8 July 2020; pp. 410–414. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanath, R.; Snyder, W.E.; Bilbro, G.L.; Sander, W.A. Demosaicking methods for bayer color arrays. J. Electron. Imaging 2002, 11, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Zuo, W.; Wang, F. Low Cost Edge Sensing for High Quality Demosaicking. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 28, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, D. An Efficient Adaptive Interpolation for Bayer CFA Demosaicking. Sens. Imaging 2019, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, K.-H.; Choi, K.; Jung, S.-W.; Ko, S.-J. Image Compression-Aware Deep Camera ISP Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 137824–137832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Cheol Kim, M.; Lee, B.D.; Hoon Sunwoo, M. Implementation of CNN based demosaicking on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2021 18th International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 6–9 October 2021; pp. 417–418. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.-Y.; Li, C.-C.; Hao, W.; Xue, Y.-F. FPGA Acceleration of Color Interpolation Algorithm Based on Gradient and Color Difference. Sens. Imaging 2020, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Duan, X.; Han, J. A Design Framework for Generating Energy-Efficient Accelerator on FPGA toward Low-Level Vision. IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst. 2024, 32, 1485–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-T.; Isikdogan, L.F.; Rao, S.; Nayak, B.; Gerasimow, T.; Sutic, A.; Ain-kedem, L.; Michael, G. VisionISP: Repurposing the Image Signal Processor for Computer Vision Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 4624–4628. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.; Li, H.; Tan, Y.; Ding, P.L.K.; Li, B. A Two-Stage Convolutional Neural Network for Joint Demosaicking and Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 4238–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.-H.; Cheng, M.-M.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Yang, M.-H.; Torr, P. Res2Net: A New Multi-Scale Backbone Architecture. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehret, T.; Davy, A.; Arias, P.; Facciolo, G. Joint Demosaicking and Denoising by Fine-Tuning of Bursts of Raw Images. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8867–8876. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and Training of Neural Networks for Efficient Integer-Arithmetic-Only Inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 2704–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Fowlkes, C.; Tal, D.; Malik, J. A Database of Human Segmented Natural Images and Its Application to Evaluating Segmentation Algorithms and Measuring Ecological Statistics. In Proceedings of the Eighth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–14 July 2001; Volume 2, pp. 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, E. Frequency-Domain Methods for Demosaicking of Bayer-Sampled Color Images. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2005, 12, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Duanmu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yong, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Waterloo Exploration Database: New Challenges for Image Quality Assessment Models. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-B.; Singh, A.; Ahuja, N. Single Image Super-Resolution from Transformed Self-Exemplars. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 5197–5206. [Google Scholar]

- Agustsson, E.; Timofte, R. NTIRE 2017 Challenge on Single Image Super-Resolution: Dataset and Study. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Lee, K.M. Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-L.; Ma, E.-D. VLSI Implementation of an Adaptive Edge-Enhanced Color Interpolation Processor for Real-Time Video Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2014, 24, 1982–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-L.; Chang, H.-R.; Lin, T.-L. Ultra-low-cost Colour Demosaicking VLSI Design for Real-time Video Applications. Electron. Lett. 2014, 50, 1585–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan, V.; Mohanty, N.; Ramanathan, S. An Area-Efficient Systolic Architecture for Real-Time VLSI Finite Impulse Response Filters. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on VLSI Design, Bombay, India, 3–6 January 1993; IEEE: Bombay, India, 1993; pp. 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa, K.; Parks, T.W. Adaptive homogeneity-directed demosaicing algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2003 International Conference on Image Processing (Cat. No.03CH37429), Barcelona, Spain, 14–17 September 2003; Volume 3, pp. 360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Pekkucuksen, I.; Altunbasak, Y. Gradient Based Threshold Free Color Filter Array Interpolation. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Hong Kong, China, 26–29 September 2010; pp. 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K.; Anastassiou, D. Subpixel Edge Localization and the Interpolation of Still Images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1995, 4, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, Z.; Lu, A.; Li, Y.; Chang, S.-E.; Ma, X.; Lin, X.; Fang, Z. FILM-QNN: Efficient FPGA Acceleration of Deep Neural Networks with Intra-Layer, Mixed-Precision Quantization. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays, Virtual, 27 February–1 March 2022; pp. 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z. A Flexible and Efficient FPGA Accelerator for Various Large-Scale and Lightweight CNNs. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2022, 69, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, T.; Zhao, Z. A High-Performance FPGA-Based Depthwise Separable Convolution Accelerator. Electronics 2023, 12, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Su, Z.; Luo, J.; Wang, Z. A Unified Acceleration Solution Based on Deformable Network for Image Pixel Processing. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 3629–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Computational Capability | Camera Count |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | <1 TOPS | 1 |

| L2 | >10 TOPS | 5+ |

| L3 | >100 TOPS | 8+ |

| L4 | >500 TOPS | 10+ |

| L5 | >1000 TOPS | 12+ |

| Node | Input Feature Map | Output Feature Map | Params |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-0 | [64, 3, 128, 128] | [64, 4, 64, 64] | 52 |

| 1-1 | [64, 4, 64, 64] | [64, 64, 64, 64] | 2368 |

| 2-0 | [64, 64, 64, 64] | [64, 64, 64, 64] | 896 |

| 2-1 | [64, 64, 64, 64] | [64, 64, 64, 64] | 4160 |

| 3-0 | [64, 64, 64, 64] | [64, 16, 64, 64] | 2304 |

| 3-1 | [64, 64, 64, 64] | [64, 64, 64, 64] | 10,668 |

| 4-0 | [64, 64, 64, 64] | [64, 12, 64, 64] | 780 |

| 4-1 | [64, 12, 64, 64] | [64, 6, 128, 128] | 147 |

| 4-2 | [64, 6, 128, 128] | [64, 3, 128, 128] | 21 |

| Model PSNR/SSIM | Kodak24 | McMaster | DIV2K |

|---|---|---|---|

| σ = 5 σ = 10 σ = 15 | σ = 5 σ = 10 σ = 15 | σ = 5 σ = 10 σ = 15 | |

| SC | 34.65/31.49/28.82 | 33.58/31.53/28.93 | 34.90/31.95/29.22 |

| 0.9380/0.7756/0.7081 | 0.9417/0.9004/0.8014 | 0.9387/0.8928/0.8025 | |

| SC-P | 34.55/31.48/28.77 | 33.55/31.19/28.90 | 34.90/31.92/29.18 |

| 0.9393/0.8815/0.7889 | 0.9479/0.9033/0.8295 | 0.9462/0.8933/0.8021 | |

| SC-DEP | 34.51/31.38/28.31 | 33.46/31.11/28.56 | 34.89/31.83/28.77 |

| 0.9389/0.8742/0.7566 | 0.9454/0.8958/0.8000 | 0.9453/0.8845/0.7700 | |

| SC-DEP-P | 33.94/30.81/27.85 | 32.91/30.58/28.09 | 33.95/31.27/28.31 |

| 0.9195/0.8581/0.7330 | 0.9217/0.8747/0.7796 | 0.9170/0.8631/0.7499 |

| Datasets | L.R. | H.R. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kodak | McMaster | Waterloo | Average | Urban100 | DIV2K | Flickr2K | Average | ||

| Method | PREC. | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM | PSNR/SSIM |

| BI [63] | FP32 | 29.46/0.5546 | 33.49/0.5234 | 28.52/- | 30.49/0.539 | 31.43/0.7453 | 33.28/0.6930 | 35.26/0.7784 | 33.32/0.7389 |

| EECP [58] | / | 33.90/- | 29.08/- | 28.62/0.5043 | 30.53/0.5043 | 30.52/0.6623 | 34.15/0.7970 | -/- | 32.34/0.7297 |

| FPCD [59] | / | 33.57/- | 30.25/- | 34.52/- | 32.78/- | -/- | 35.52/- | -/- | 35.52/- |

| ACDS [60] | / | 29.80/0.5043 | 30.04/0.4432 | 29.68/0.5234 | 29.84/0.4903 | 32.06/0.6856 | 34.69/0.9068 | -/- | 33.38/0.7947 |

| CIAG [45] | FP32 | 37.36/0.9658 | 30.49/0.8604 | 29.08/0.9256 | 32.31/0.9173 | 32.54/0.8827 | 30.51/0.9021 | 35.87/0.8689 | 32.97/0.8846 |

| SUIDC [10] | INT8 | 34.94/0.8302 | 32.60/0.9052 | 29.83/0.9120 | 32.46/0.8825 | 32.04/0.8522 | 35.26/0.9020 | 36.23/0.9256 | 34.51/0.8933 |

| TS [44] | FIX | 35.47/- | 29.83/- | 31.89/ | 32.40/ | 34.21/- | 33.26/- | 35.31/- | 34.23/- |

| Zhou [46] | BOPs | 32.24/0.9154 | 37.24/0.9794 | 29.92/0.8739 | 33.13/0.9229 | 31.16/0.8958 | -/- | 31.16/0.8958 | |

| Guan [27] | 8,8 * | 33.73/0.8935 | -/- | -/- | 33.73/0.8935 | -/- | -/- | -/- | -/- |

| LJDD | FP32 | 38.35/0.9831 | 35.76/0.9785 | 36.29/0.9847 | 36.8/0.9821 | 34.56/0.9860 | 38.44/0.9830 | 39.02/0.9871 | 37.34/0.9854 |

| LJDD * | 8,16 * | 36.09/0.9741 | 34.16/0.9619 | 34.35/0.9731 | 34.87/0.9697 | 32.68/0.9676 | 35.98/0.9704 | 36.04/0.9716 | 34.9/0.9699 |

| [39] 20’ | [45] 20’ | [64] 21’ | [65] 22’ | [66] 23’ | [44] 21’ | [27] 22’ | CPU | GPU | Ours 1 | Ours 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasks | Traditional DM&DN Algorithm | Other Acceleration Solutions | DM&DN Based on Models | ||||||||

| Platform | Zynq-7045 | Zynq 7020 | ZCU102 | Intel Arria10 | Arria10 GX 660 | Virtex-7 | Zynq UltraScale+ | i7-10700K | RTX3060 | ZynqUtraScale + XCZU15EG | |

| Precision (W,A) | fixed | INT8 | Mixed | 8bit-fixed | 12-8fixed | INT16 | INT8 | FP32 | 8–16*fixed | ||

| Parallelism | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 16 |

| Clock (MHz) | 101 | 120 | 100 | 200 | 225 | 120 | 250 | 4360 | 1777 | 275 | |

| DSP Used | 21 | 9 | 214 | 607 | 1082 | 81 | 2304 | - | - | 304 | 1168 |

| BRAM | 124 (22.75%) | 12 (8.57%) | 126.5 | 769 (36%) | 216 (24%) | 15 (1.46%) | 544 (59.65%) | - | - | 137 (18.41%) | 322 (43.28%) |

| Logic | 1136 (LUT) 1241 (FF) | 8997 (LUT) 9933 (FF) | 39.1k (LUT) /-(FF) | 207k (ALM) | 28.2k (LUTs 10.3%) 14k (FFs 2.6%) | 1605 (LUT) 3741 (FF) | 20.50k (LUT) 29.35k (FF) | - | - | 18.00k (LUT 3.42%) 18.98k (2.78%) | 51.60k (LUT 9.82%) 147.56k (FF 21.62%) |

| Computation Efficiency (GOPS/DSP) | - | - | 0.137 | 0.13 | 0.24 | - | 0.23 | - | - | 0.48 1 | 0.25 2 |

| Power(W) | 3.5 | - | 16.51 | - | - | 80.8 | 38.66 | 3.92 1 | 6.66 2 | ||

| Energy Efficiency (GOPS/W) | 9.77 | - | 15.72 | - | - | 0.512 | 1.53 | 37.15 1 | 43.72 2 | ||

| PE/DSP Reuse | - | - | N/N | N/N | Y/N | N/N | Y/N | - | - | Y/Y | |

| Kernel Range/Stride | - | K = 3 | K = 3/K = 1 | K = 3 | K/S = 3/1 | K = 1,3/S = 1 | - | - | K/S = Wide range | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y. A Hardware-Friendly Joint Denoising and Demosaicing System Based on Efficient FPGA Implementation. Micromachines 2026, 17, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010044

Wang J, Wang X, Shen Y. A Hardware-Friendly Joint Denoising and Demosaicing System Based on Efficient FPGA Implementation. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiqing, Xiang Wang, and Yu Shen. 2026. "A Hardware-Friendly Joint Denoising and Demosaicing System Based on Efficient FPGA Implementation" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010044

APA StyleWang, J., Wang, X., & Shen, Y. (2026). A Hardware-Friendly Joint Denoising and Demosaicing System Based on Efficient FPGA Implementation. Micromachines, 17(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010044