Advancing In Vitro Microfluidic Models for Pressure-Induced Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration: Current Insights and Future Directions from a Biomechanical Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pressure Modes in Current In Vitro Studies on Pressure-Induced Degeneration of RGCs: Static or Dynamic?

2.1. Static Pressure Models

2.2. Dynamic Pressure Models

3. The Direct and Indirect Pressure Effect on Pressure-Induced Degeneration of RGCs

3.1. Direct Pressure Effect on RGCs

3.2. Indirect Pressure Effect on RGCs

4. Development of Advanced In Vitro Microfluidic Models for Studying Degeneration of RGCs

4.1. Unidirectional Alignment of RGC Axons

4.2. Co-Culture Systems That Allow Cell–Cell Interactions Between Retinal Cell Types

4.3. The Control of Various Biomechanical Parameters That RGCs Experience In Vivo

4.3.1. Tissue Biomechanics

4.3.2. Fluctuating IOP Levels

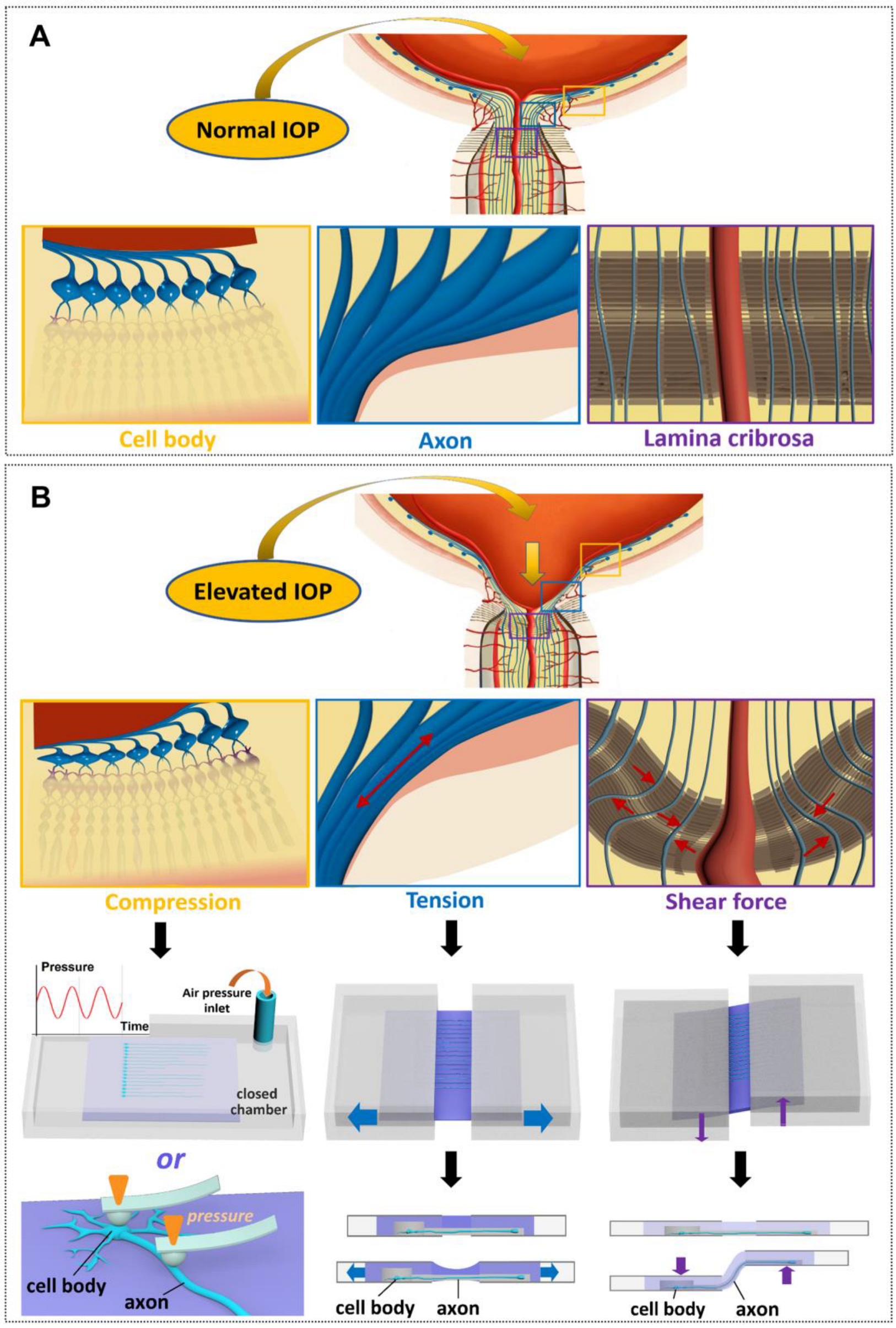

4.3.3. Mechanical Stresses Acting on RGC Axons Due to the Deformation of Laminar Cribrosa

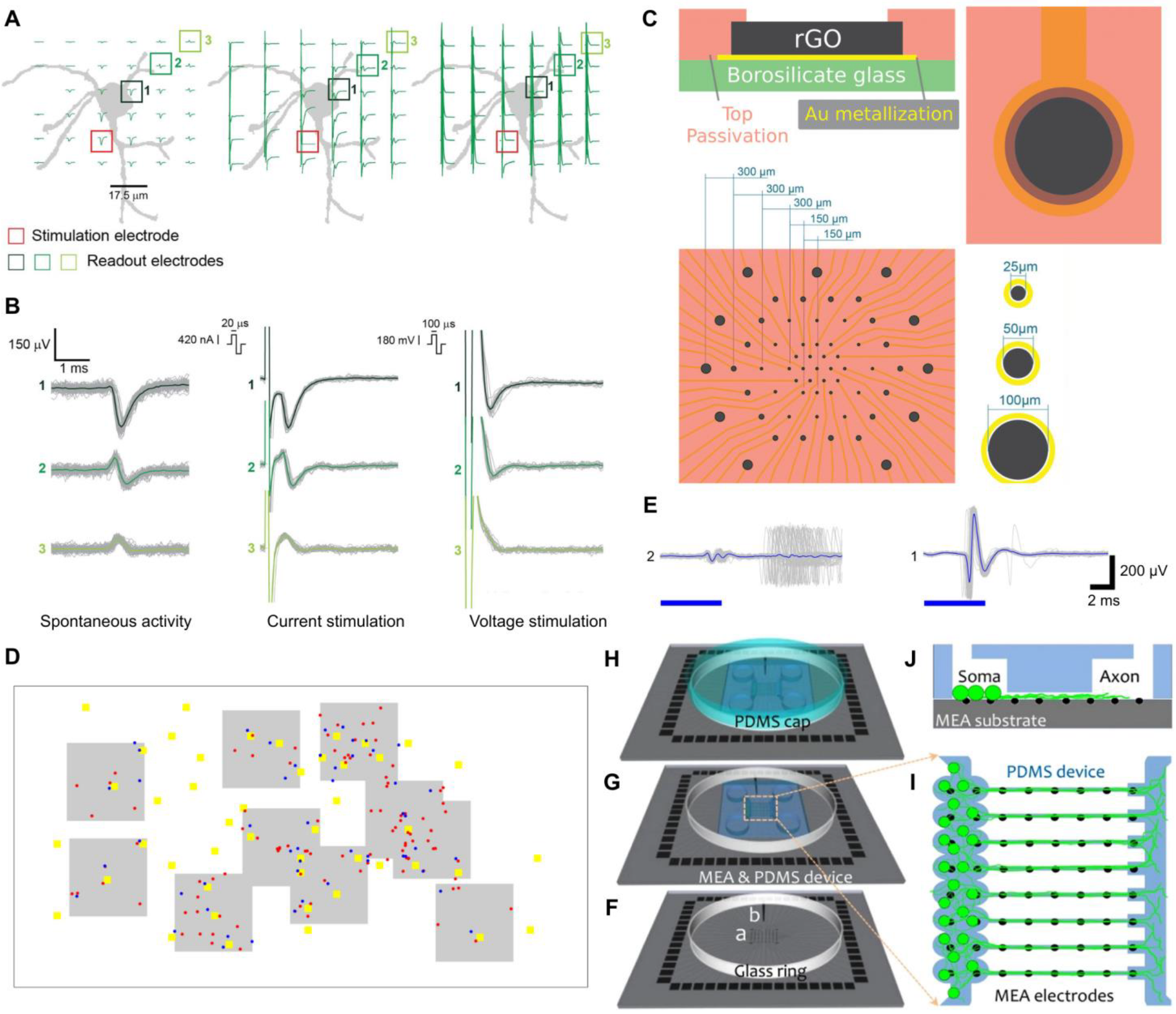

4.4. Merging Microfluidics with Electrode Technology to Study RGC Electroconductivity

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tham, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.-Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden through 2040: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhenni, R.A.; Dunmire, J.; Sewell, A.; Edward, D.P. Animal Models of Glaucoma. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 692609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.C.; Moore, C.G.; Deppmeier, L.M.H.; Gold, B.G.; Meshul, C.K.; Johnson, E.C. A Rat Model of Chronic Pressure-induced Optic Nerve Damage. Exp. Eye Res. 1997, 64, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.; Morrison, J.C.; Farrell, S.; Deppmeier, L.; Moore, C.G.; McGinty, M.R. The Effect of Chronically Elevated Intraocular Pressure on the Rat Optic Nerve Head Extracellular Matrix. Exp. Eye Res. 1996, 62, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, R.J.; Chidlow, G.; Wood, J.P.M.; Crowston, J.G.; Goldberg, I. Definition of glaucoma: Clinical and experimental concepts. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2012, 40, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, M.; Picciani, R.G.; Lee, R.K.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Aqueous humor dynamics: A review. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2010, 4, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, R.F. Flow of aqueous humor in humans [The Friedenwald Lecture]. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1991, 32, 3145–3166. [Google Scholar]

- Urcola, J.H.; Hernández, M.; Vecino, E. Three experimental glaucoma models in rats: Comparison of the effects of intraocular pressure elevation on retinal ganglion cell size and death. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 83, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, J.; van Oterendorp, C.; Stoykow, C.; Volz, C.; Jehle, T.; Boehringer, D.; Lagrèze, W.A. Evaluation of intraocular pressure elevation in a modified laser-induced glaucoma rat model. Exp. Eye Res. 2012, 104, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; House, P.; Morgan, W.; Sun, X.; Yu, D.-Y. Developing laser-induced glaucoma in rabbits. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 27, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strouthidis, N.G.; Fortune, B.; Yang, H.; Sigal, I.A.; Burgoyne, C.F. Effect of Acute Intraocular Pressure Elevation on the Monkey Optic Nerve Head as Detected by Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 9431–9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, M.; Lindsey, J.D.; Weinreb, R.N. Ocular Hypertension in Mice with a Targeted Type I Collagen Mutation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 1581–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarie, J.M.; Link, B.A. The Primary open-angle glaucoma gene WDR36 functions in ribosomal RNA processing and interacts with the p53 stress–response pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 2474–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toris, C.B.; Zhan, G.-L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Zhao, J.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Camras, C.B.; Yablonski, M.E. Aqueous Humor Dynamics in Monkeys with Laser-Induced Glaucoma. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 16, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Harada, C.; Nakamura, K.; Quah, H.-M.A.; Okumura, A.; Namekata, K.; Saeki, T.; Aihara, M.; Yoshida, H.; Mitani, A.; et al. The potential role of glutamate transporters in the pathogenesis of normal tension glaucoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitesides, G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Matthews, B.D.; Mammoto, A.; Montoya-Zavala, M.; Hsin, H.Y.; Ingber, D.E. Reconstituting Organ-Level Lung Functions on a Chip. Science 2010, 328, 1662–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ali, J.; Sorger, P.K.; Jensen, K.F. Cells on chips. Nature 2006, 442, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leske, M.C.; Heijl, A.; Hussein, M.; Bengtsson, B.; Hyman, L.; Komaroff, E. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: The early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2003, 121, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.; Yu, Y.; Ng, S.H.; Mak, H.K.; Yip, Y.W.Y.; van der Merwe, Y.; Ren, T.; Yung, J.S.Y.; Biswas, S.; Cao, X.; et al. Intracameral injection of a chemically cross-linked hydrogel to study chronic neurodegeneration in glaucoma. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, K.; Tanna, A.P.; De Moraes, C.G.; Camp, A.S.; Weinreb, R.N. Review of the measurement and management of 24-hour intraocular pressure in patients with glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 65, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, K.; Weinreb, R.N.; Medeiros, F.A. Is 24-hour intraocular pressure monitoring necessary in glaucoma? Semin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 28, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidl, M.C.; Choi, C.J.; Syed, Z.A.; Melki, S.A. Intraocular pressure fluctuation and glaucoma progression: What do we know? Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 98, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, E.W.; Bahinski, A.; Huh, D. Organs-on-chips at the frontiers of drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.N.; Ingber, D.E. Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tao, T.; Su, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, Y.; Qin, J. A disease model of diabetic nephropathy in a glomerulus-on-a-chip microdevice. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.-K.; Liu, Q.; Kim, K.-Y.; Crowston, J.G.; Lindsey, J.D.; Agarwal, N.; Ellisman, M.H.; Perkins, G.A.; Weinreb, R.N. Elevated Hydrostatic Pressure Triggers Mitochondrial Fission and Decreases Cellular ATP in Differentiated RGC-5 Cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 2145–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ju, W.-K.; Crowston, J.G.; Xie, F.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Lindsey, J.D.; Weinreb, R.N. Oxidative Stress Is an Early Event in Hydrostatic Pressure–Induced Retinal Ganglion Cell Damage. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 4580–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Rajabi, S.; Pedrigi, R.M.; Overby, D.R.; Read, A.T.; Ethier, C.R. In Vitro Models for Glaucoma Research: Effects of Hydrostatic Pressure. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 6329–6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, M.H.; Elvas, F.; Boia, R.; Gonçalves, F.Q.; Cunha, R.A.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Santiago, A.R. Adenosine A2AR blockade prevents neuroinflammation-induced death of retinal ganglion cells caused by elevated pressure. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumpio, B.E.; Widmann, M.D.; Ricotta, J.; Awolesi, M.A.; Watase, M. Increased ambient pressure stimulates proliferation and morphologic changes in cultured endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1994, 158, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappington, R.M.; Chan, M.; Calkins, D.J. Interleukin-6 Protects Retinal Ganglion Cells from Pressure-Induced Death. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 2932–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappington, R.M.; Sidorova, T.; Long, D.J.; Calkins, D.J. TRPV1: Contribution to retinal ganglion cell apoptosis and increased intracellular Ca2+ with exposure to hydrostatic pressure. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agar, A.; Yip, S.S.; Hill, M.A.; Coroneo, M.T. Pressure related apoptosis in neuronal cell lines. J. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Mak, H.K.; Chan, Y.K.; Lin, C.; Kong, C.; Leung, C.K.S.; Shum, H.C. An in vitro pressure model towards studying the response of primary retinal ganglion cells to elevated hydrostatic pressures. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingensiep, C.; Schaffrath, K.; Walter, P.; Johnen, S. Effects of Hydrostatic Pressure on Electrical Retinal Activity in a Multielectrode Array-Based ex vivo Glaucoma Acute Model. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 831392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, K.; Iizuka, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Araie, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Tsukahara, S. Molecular and Cellular Reactions of Retinal Ganglion Cells and Retinal Glial Cells under Centrifugal Force Loading. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 3778–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, Y. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure on the expression of glutamine synthetase in rat retinal Müller cells cultured in vitro. Exp. Ther. Med. 2011, 2, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, V.; Novelli, E.; Vozzi, G.; Scarpa, C.; Caleo, M.; Ahluwalia, A.; Solini, A.; Santini, E.; Parisi, V.; Di Virgilio, F.; et al. Acute retinal ganglion cell injury caused by intraocular pressure spikes is mediated by endogenous extracellular ATP. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 2741–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.; Aldarwesh, A.; Rhodes, J.D.; Broadway, D.C.; Everitt, C.; Sanderson, J. Hydrostatic pressure does not cause detectable changes in survival of human retinal ganglion cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Fu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, Z. Organ-on-a-Chip Systems: Microengineering to Biomimic Living Systems. Small 2016, 12, 2253–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappington, R.M.; Calkins, D.J. Pressure-Induced Regulation of IL-6 in Retinal Glial Cells: Involvement of the Ubiquitin/Proteasome Pathway and NFκB. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 3860–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Shahidullah, M.; Delamere, N.A. Hydrostatic pressure-induced release of stored calcium in cultured rat optic nerve head astrocytes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 3129–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.H.; Zhou, Z.L.; Qian, J.; Lin, Y.; Ngan, A.H.W.; Gao, H. Volumetric Deformation of Live Cells Induced by Pressure-Activated Cross-Membrane Ion Transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 118101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Yoshitomi, T.; Zorumski, C.F.; Izumi, Y. Effects of acutely elevated hydrostatic pressure in a rat ex vivo retinal preparation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 6414–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Yoshitomi, T.; Covey, D.F.; Zorumski, C.F.; Izumi, Y. TSPO activation modulates the effects of high pressure in a rat ex vivo glaucoma model. Neuropharmacology 2016, 111, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.P.; Pasquale, L.R. Clinical characteristics and current treatment of glaucoma. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a017236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.M.; Farrell, R.A.; Langham, M.E.; O’Brien, V.; Schilder, P. Estimation of pulsatile ocular blood flow from intraocular pressure. Acta Ophthalmol. Suppl. 1989, 191, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion, I.B.; Harris, A.; Siesky, B.; Shulman, S.; McCranor, L.; Garzozi, H.J. Pulsatile ocular blood flow: Relationship with flow velocities in vessels supplying the retina and choroid. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 882–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findl, O.; Rainer, G.; Dallinger, S.; Dorner, G.; Polak, K.; Kiss, B.; Georgopoulos, M.; Vass, C.; Schmetterer, L. Assessment of optic disk blood flow in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 130, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.G.; von Rückmann, A.; Pillunat, L.E. Topical carbonic anhydrase inhibition increases ocular pulse amplitude in high tension primary open angle glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 82, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.; Nelson, P.; O’Brien, C. A comparison of ocular blood flow in untreated primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 126, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Poinoosawmy, D.; Bunce, C.V.; O’Brien, C.; Hitchings, R.A. Pulsatile ocular blood flow investigation in asymmetric normal tension glaucoma and normal subjects. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 82, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulsteke, C.; Stalmans, I.; Fieuws, S.; Zeyen, T. Correlation between ocular pulse amplitude measured by dynamic contour tonometer and visual field defects. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 246, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjabi, O.S.; Ho, H.-K.V.; Kniestedt, C.; Bostrom, A.G.; Stamper, R.L.; Lin, S.C. Intraocular Pressure and Ocular Pulse Amplitude Comparisons in Different Types of Glaucoma Using Dynamic Contour Tonometry. Curr. Eye Res. 2009, 31, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, C.; Bachmann, L.M.; Robert, Y.C.; Thiel, M.A. Ocular Pulse Amplitude in Healthy Subjects as Measured by Dynamic Contour Tonometry. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2006, 124, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnichels, S.; Paquet-Durand, F.; Löscher, M.; Tsai, T.; Hurst, J.; Joachim, S.C.; Klettner, A. Retina in a dish: Cell cultures, retinal explants and animal models for common diseases of the retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 81, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bergen, N.J.; Wood, J.P.M.; Chidlow, G.; Trounce, I.A.; Casson, R.J.; Ju, W.-K.; Weinreb, R.N.; Crowston, J.G. Recharacterization of the RGC-5 Retinal Ganglion Cell Line. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 4267–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, R.R.; Clark, A.F.; Daudt, D.; Vishwanatha, J.K.; Yorio, T. A Forensic Path to RGC-5 Cell Line Identification: Lessons Learned. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 5712–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ze’ev, A.; Robinson, G.S.; Bucher, N.L.; Farmer, S.R. Cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions differentially regulate the expression of hepatic and cytoskeletal genes in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 2161–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.B.; Srigunapalan, S.; Wheeler, A.R.; Simmons, C.A. A 3D microfluidic platform incorporating methacrylated gelatin hydrogels to study physiological cardiovascular cell-cell interactions. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 2591–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Koito, H.; Li, J.; Han, A. Microfluidic compartmentalized co-culture platform for CNS axon myelination research. Biomed. Microdevices 2009, 11, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, K.; Lee, M.; Shin, H.-W.; Chung, S. In vitro nasal mucosa gland-like structure formation on a chip. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, J.; Boyle, J.; Pielen, A.; Lagrèze, W.A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors sodium butyrate and valproic acid delay spontaneous cell death in purified rat retinal ganglion cells. Mol. Vis. 2011, 17, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Li, T.; Hu, J.; Zhou, X.; Wu, J.; Wu, Q. Comparative analysis of three purification protocols for retinal ganglion cells from rat. Mol. Vis. 2016, 22, 387–400. [Google Scholar]

- Nafian, F.; Kamali Doust Azad, B.; Yazdani, S.; Rasaee, M.J.; Daftarian, N. A lab-on-a-chip model of glaucoma. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, G.; Li, L.Y.; Patil, R.V.; Wax, M.B. TNF-alpha and TNF-alpha receptor-1 in the retina of normal and glaucomatous eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Neufeld, A.H. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: A potentially neurodestructive cytokine produced by glia in the human glaucomatous optic nerve head. Glia 2000, 32, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantoulas, C.; Farmer, C.; Machado, P.; Baba, K.; McMahon, S.B.; Raouf, R. Probing Functional Properties of Nociceptive Axons Using a Microfluidic Culture System. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennet, D.; Estlack, Z.; Reid, T.; Kim, J. A microengineered human corneal epithelium-on-a-chip for eye drops mass transport evaluation. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Hao, R.; Du, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Gu, Z.; Yang, H. A human cornea-on-a-chip for the study of epithelial wound healing by extracellular vesicles. iScience 2022, 25, 104200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Fu, H.; Bazinet, L.; Birsner, A.E.; D’Amato, R.J. A Method for Developing Novel 3D Cornea-on-a-Chip Using Primary Murine Corneal Epithelial and Endothelial Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Yao, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, L.; Luo, C.; Yang, W.; Li, L. A biomimetic human disease model of bacterial keratitis using a cornea-on-a-chip system. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 5239–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Lee, S.; Lee, B.J.; Son, K.; Jeon, N.L.; Kim, J.H. Wet-AMD on a Chip: Modeling Outer Blood-Retinal Barrier In Vitro. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 7, 1700028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arık, Y.B.; Buijsman, W.; Loessberg-Zahl, J.; Cuartas-Vélez, C.; Veenstra, C.; Logtenberg, S.; Grobbink, A.M.; Bergveld, P.; Gagliardi, G.; den Hollander, A.I.; et al. Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip model of the outer blood–retinal barrier with clinically relevant read-outs for tissue permeability and vascular structure. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Song, Y.; Jolly, A.L.; Hwang, T.; Kim, S.; Lee, B.; Jang, J.; Jo, D.H.; Baek, K.; Liu, T.L.; et al. High-Throughput Microfluidic 3D Outer Blood-Retinal Barrier Model in a 96-Well Format: Analysis of Cellular Interactions and Barrier Function in Retinal Health and Disease. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2400634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurissen, T.L.; Spielmann, A.J.; Schellenberg, G.; Bickle, M.; Vieira, J.R.; Lai, S.Y.; Pavlou, G.; Fauser, S.; Westenskow, P.D.; Kamm, R.D.; et al. Modeling early pathophysiological phenotypes of diabetic retinopathy in a human inner blood-retinal barrier-on-a-chip. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.M.; de Haan, P.; Ronaldson-Bouchard, K.; Kim, G.-A.; Ko, J.; Rho, H.S.; Chen, Z.; Habibovic, P.; Jeon, N.L.; Takayama, S.; et al. A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.-E.; Mustafaoglu, N.; Herland, A.; Hasselkus, R.; Mannix, R.; FitzGerald, E.A.; Prantil-Baun, R.; Watters, A.; Henry, O.; Benz, M.; et al. Hypoxia-enhanced Blood-Brain Barrier Chip recapitulates human barrier function and shuttling of drugs and antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatine, G.D.; Barrile, R.; Workman, M.J.; Sances, S.; Barriga, B.K.; Rahnama, M.; Barthakur, S.; Kasendra, M.; Lucchesi, C.; Kerns, J.; et al. Human iPSC-Derived Blood-Brain Barrier Chips Enable Disease Modeling and Personalized Medicine Applications. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 995–1005.e1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.L.; Groenendijk, L.; Overdevest, R.; Fowke, T.M.; Annida, R.; Mocellin, O.; de Vries, H.E.; Wevers, N.R. Human BBB-on-a-chip reveals barrier disruption, endothelial inflammation, and T cell migration under neuroinflammatory conditions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, K.-T.; Lee, J.S.; Shin, J.; Cui, B.; Yang, K.; Choi, Y.S.; Choi, N.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.-H.; et al. Fungal brain infection modelled in a human-neurovascular-unit-on-a-chip with a functional blood–brain barrier. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Koo, B.-K.; Knoblich, J.A. Human organoids: Model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Cai, X.; Guan, R. Recent progress on the organoids: Techniques, advantages and applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 185, 117942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.-N.; Jin, Y.; An, Y.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.; Choi, W.-Y.; Koo, D.-J.; Yu, W.; et al. Microfluidic device with brain extracellular matrix promotes structural and functional maturation of human brain organoids. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, I.; Grebenyuk, S.; Abdel Fattah, A.R.; Rustandi, G.; Pilkington, T.; Verfaillie, C.; Ranga, A. Engineering neurovascular organoids with 3D printed microfluidic chips. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintard, C.; Tubbs, E.; Jonsson, G.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Werschler, N.; Laporte, C.; Pitaval, A.; Bah, T.-S.; Pomeranz, G.; et al. A microfluidic platform integrating functional vascularized organoids-on-chip. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Tian, C.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Sun, A.X.; McCracken, K.; Tchieu, J.; Gu, M.; Mackie, K.; Guo, F. Vascular network-inspired diffusible scaffolds for engineering functional midbrain organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 824–837.e825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebenyuk, S.; Abdel Fattah, A.R.; Kumar, M.; Toprakhisar, B.; Rustandi, G.; Vananroye, A.; Salmon, I.; Verfaillie, C.; Grillo, M.; Ranga, A. Large-scale perfused tissues via synthetic 3D soft microfluidics. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, T.; Duenki, T.; Chow, S.Y.A.; Ikegami, Y.; Beaubois, R.; Levi, T.; Nakagawa-Tamagawa, N.; Hirano, Y.; Ikeuchi, Y. Complex activity and short-term plasticity of human cerebral organoids reciprocally connected with axons. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Ozaki, H.; Morikawa, A.; Shiraiwa, K.; Pin, A.P.; Salem, A.G.; Phommahasay, K.A.; Sugita, B.K.; Vu, C.H.; Hammad, S.M.; et al. Proof of concept for brain organoid-on-a-chip to create multiple domains in forebrain organoids. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 3749–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshksayan, K.; Harihara, A.; Mondal, S.; Hegarty, E.; Atherly, T.; Sahoo, D.K.; Jergens, A.E.; Mochel, J.P.; Allenspach, K.; Zoldan, J.; et al. OrganoidChip facilitates hydrogel-free immobilization for fast and blur-free imaging of organoids. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Yamaoka, N.; Imaizumi, Y.; Nagashima, T.; Furutani, T.; Ito, T.; Okada, Y.; Honda, H.; Shimizu, K. Development of a human neuromuscular tissue-on-a-chip model on a 24-well-plate-format compartmentalized microfluidic device. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duc, P.; Vignes, M.; Hugon, G.; Sebban, A.; Carnac, G.; Malyshev, E.; Charlot, B.; Rage, F. Human neuromuscular junction on micro-structured microfluidic devices implemented with a custom micro electrode array (MEA). Lab Chip 2021, 21, 4223–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, M.; Dittlau, K.S.; Beretti, F.; Yedigaryan, L.; Zavatti, M.; Cortelli, P.; Palumbo, C.; Bertucci, E.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Sampaolesi, M.; et al. Human Neuromuscular Junction on a Chip: Impact of Amniotic Fluid Stem Cell Extracellular Vesicles on Muscle Atrophy and NMJ Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoklund Dittlau, K.; Krasnow, E.N.; Fumagalli, L.; Vandoorne, T.; Baatsen, P.; Kerstens, A.; Giacomazzi, G.; Pavie, B.; Rossaert, E.; Beckers, J.; et al. Human motor units in microfluidic devices are impaired by FUS mutations and improved by HDAC6 inhibition. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, N.; Potey, A.; Blond, F.; Guerin, C.; Baudouin, C.; Peyrin, J.-M.; Brignole-Baudouin, F.; Réaux-Le Goazigo, A. Assessment of corneal nerve regeneration after axotomy in a compartmentalized microfluidic chip model with automated 3D high resolution live-imaging. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1417653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneau, N.; Potey, A.; Vitoux, M.-A.; Magny, R.; Guerin, C.; Baudouin, C.; Peyrin, J.-M.; Brignole-Baudouin, F.; Réaux-Le Goazigo, A. Corneal neuroepithelial compartmentalized microfluidic chip model for evaluation of toxicity-induced dry eye. Ocul. Surf. 2023, 30, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wong, H.L.; Ip, Y.L.; Chu, W.Y.; Li, M.S.; Saha, C.; Shih, K.C.; Chan, Y.K. Current microfluidic platforms for reverse engineering of cornea. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalkader, R.; Kamei, K.-i. Multi-corneal barrier-on-a-chip to recapitulate eye blinking shear stress forces. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kado Abdalkader, R.; Chaleckis, R.; Fujita, T.; Kamei, K.-i. Modeling dry eye with an air–liquid interface in corneal epithelium-on-a-chip. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Byun, W.Y.; Alisafaei, F.; Georgescu, A.; Yi, Y.-S.; Massaro-Giordano, M.; Shenoy, V.B.; Lee, V.; Bunya, V.Y.; Huh, D. Multiscale reverse engineering of the human ocular surface. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achberger, K.; Probst, C.; Haderspeck, J.; Bolz, S.; Rogal, J.; Chuchuy, J.; Nikolova, M.; Cora, V.; Antkowiak, L.; Haq, W.; et al. Merging organoid and organ-on-a-chip technology to generate complex multi-layer tissue models in a human retina-on-a-chip platform. eLife 2019, 8, e46188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Gong, Y.; Zou, T.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, C.; Mo, L.; Kang, J.; Fan, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, J. A controllable perfusion microfluidic chip for facilitating the development of retinal ganglion cells in human retinal organoids. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 3820–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabbe, E.; Pelaez, D.; Agarwal, A. Retinal organoid chip: Engineering a physiomimetic oxygen gradient for optimizing long term culture of human retinal organoids. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 1626–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Linares, A.; Wareham, L.K.; Walmsley, T.S.; Holden, J.M.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Pan, Z.; Xu, Y.-Q.; Li, D. Dynamic Observation of Retinal Response to Pressure Elevation in a Microfluidic Chamber. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12297–12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, E.L.; Stamer, D.W.; Au, S.; Overby, D.R. Co-culture with trabecular meshwork cells promotes barrier function in an organ-on-chip model of Schlemm’s canal inner endothelial wall. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 2500. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, E.L.; Stamer, D.W.; Wan, Z.; Kamm, R.; Au, S.; Overby, D.R. Building an Organ-on-Chip Model of the Inner Wall Endothelium of Schlemm’s Canal. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 3490. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.; Kolarzyk, A.M.; Stamer, W.D.; Lee, E. Human ocular fluid outflow on-chip reveals trabecular meshwork-mediated Schlemm’s canal endothelial dysfunction in steroid-induced glaucoma. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 4, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, J.; van der List, D.; Wang, G.Y.; Chalupa, L.M. Morphological properties of mouse retinal ganglion cells. Neuroscience 2006, 140, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.L.; Espinosa, J.S.; Xu, Y.; Davidson, N.; Kovacs, G.T.A.; Barres, B.A. Retinal Ganglion Cells Do Not Extend Axons by Default: Promotion by Neurotrophic Signaling and Electrical Activity. Neuron 2002, 33, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.K.; Yung, J.S.Y.; Weinreb, R.N.; Ng, S.H.; Cao, X.; Ho, T.Y.C.; Ng, T.K.; Chu, W.K.; Yung, W.H.; Choy, K.W.; et al. MicroRNA-19a-PTEN Axis Is Involved in the Developmental Decline of Axon Regenerative Capacity in Retinal Ganglion Cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenaccio, A.; Llavero Hurtado, M.; Diaz, P.; Lamont, D.J.; Wishart, T.M.; Court, F.A. Molecular analysis of axonal-intrinsic and glial-associated co-regulation of axon degeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Blurton-Jones, M.; Rhee, S.W.; Cribbs, D.H.; Cotman, C.W.; Jeon, N.L. A microfluidic culture platform for CNS axonal injury, regeneration and transport. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagella, P.; Neto, E.; Jiménez-Rojo, L.; Lamghari, M.; Mitsiadis, T.A. Microfluidics co-culture systems for studying tooth innervation. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijssen, J.; Aguila, J.; Hoogstraaten, R.; Kee, N.; Hedlund, E. Axon-Seq Decodes the Motor Axon Transcriptome and Its Modulation in Response to ALS. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 11, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Black, S.E.; Lotlikar, M.S.; Fenn, R.H.; Jorfi, M.; Kovacs, D.M.; Tanzi, R.E. Axonal generation of amyloid-β from palmitoylated APP in mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Nakanishi, T.; Ueno, M.; Itohara, S.; Yamashita, T. Netrin-G1 Regulates Microglial Accumulation along Axons and Supports the Survival of Layer V Neurons in the Postnatal Mouse Brain. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wu, T. Ultrafast Microdroplet Generation and High-Density Microparticle Arraying Based on Biomimetic Nepenthes Peristome Surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 47299–47308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Van Bergen, N.J.; Kong, G.Y.; Chrysostomou, V.; Waugh, H.S.; O’Neill, E.C.; Crowston, J.G.; Trounce, I.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in glaucoma and emerging bioenergetic therapies. Exp. Eye Res. 2011, 93, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.Y.; Van Bergen, N.J.; Trounce, I.A.; Crowston, J.G. Mitochondrial dysfunction and glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2009, 18, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, M.J.; Ng, C.P.; Lanz, H.L.; Vulto, P.; Suter-Dick, L.; Masereeuw, R. Kidney-on-a-Chip Technology for Drug-Induced Nephrotoxicity Screening. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanowicz, D.R.; Lu, H.H. Multifunction co-culture model for evaluating cell-cell interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1202, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goers, L.; Freemont, P.; Polizzi, K.M. Co-culture systems and technologies: Taking synthetic biology to the next level. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, S.; Du, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Qian, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, W. Microfluidic co-culture system for cancer migratory analysis and anti-metastatic drugs screening. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, I.D.; Boia, R.; Rodrigues-Neves, A.C.; Madeira, M.H.; Marques, C.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Santiago, A.R. Blockade of microglial adenosine A(2A) receptor suppresses elevated pressure-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death in retinal cells. Glia 2019, 67, 896–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensheimer, T.; Veerman, D.; van Oosten, E.M.; Segerink, L.; Garanto, A.; van der Meer, A.D. Retina-on-chip: Engineering functional in vitro models of the human retina using organ-on-chip technology. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 996–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Wu, J.; Liu, A.P. Advanced Microfluidic Device Designed for Cyclic Compression of Single Adherent Cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, J.; Olmos Calvo, I.; Peter, E.; Jenner, F.; Purtscher, M.; Shlager, M. Recent Advances of Biologically Inspired 3D Microfluidic Hydrogel Cell Culture Systems. J. Cell Biol. Cell Metab. 2015, 2, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.Y.; Shin, A.; Park, J.; Nagiel, A.; Lalane, R.A.; Schwartz, S.D.; Demer, J.L. Deformation of Optic Nerve Head and Peripapillary Tissues by Horizontal Duction. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 174, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, M.A.; Clark, M.E.; Bruno, L.; Girkin, C.A. In vivo optic nerve head mechanical response to intraocular and cerebrospinal fluid pressure: Imaging protocol and quantification method. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, J.C.; Girkin, C.A. Lamina cribrosa in glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Li, L.; Song, F. Study on the deformations of the lamina cribrosa during glaucoma. Acta Biomater. 2017, 55, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Jonas, J.B.; Aung, T.; Schmetterer, L.; Girard, M.J.A. Modeling the Origin of the Ocular Pulse and Its Impact on the Optic Nerve Head. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 3997–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunsmann, C.; Hammer, C.M.; Rheinlaender, J.; Kruse, F.E.; Schäffer, T.E.; Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U. Evaluation of Lamina Cribrosa and Peripapillary Sclera Stiffness in Pseudoexfoliation and Normal Eyes by Atomic Force Microscopy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 2960–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.K.; Zhang, X.; Kripke, D.F.; Weinreb, R.N. Twenty-four-Hour Intraocular Pressure Pattern Associated with Early Glaucomatous Changes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 1586–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smedt, S. Noninvasive intraocular pressure monitoring: Current insights. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2015, 9, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajiei, T.D.; Iadanza, S.; Bachmann, L.M.; Kniestedt, C. Inventory of Ocular Pulse Amplitude Values in Healthy Subjects and Patients With Ophthalmologic Illnesses: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 259, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Ding, Y.; Duan, X.; Wu, Z. Ocular pulse amplitude in different types of glaucoma using dynamic contour tonometry: Diagnosis and follow-up of glaucoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 4148–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.E.; Wang, S.S.; Good, T.A. Role of viscoelastic properties of differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells in cyclic shear stress injury. Biotechnol. Prog. 2001, 17, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorhees, A.P.; Jan, N.J.; Sigal, I.A. Effects of collagen microstructure and material properties on the deformation of the neural tissues of the lamina cribrosa. Acta Biomater. 2017, 58, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Song, F. Biomechanical research into lamina cribrosa in glaucoma. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1277–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Akagi, T.; Hangai, M.; Ohashi-Ikeda, H.; Takayama, K.; Morooka, S.; Kimura, Y.; Nakano, N.; Yoshimura, N. Alterations in the Neural and Connective Tissue Components of Glaucomatous Cupping After Glaucoma Surgery Using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Kwok, S.; Sun, J.; Pan, X.; Pavlatos, E.; Clayson, K.; Hazen, N.; Liu, J. IOP-induced regional displacements in the optic nerve head and correlation with peripapillary sclera thickness. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 200, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallfors, N.; Khan, A.; Dickey, M.D.; Taylor, A.M. Integration of pre-aligned liquid metal electrodes for neural stimulation within a user-friendly microfluidic platform. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, S.; Fiscella, M.; Marchetti, C.; Viswam, V.; Müller, J.; Frey, U.; Hierlemann, A. Single-Cell Electrical Stimulation Using CMOS-Based High-Density Microelectrode Arrays. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Shinde, A.; Illath, K.; Kar, S.; Nagai, M.; Tseng, F.-G.; Santra, T.S. Microfluidic platforms for single neuron analysis. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 13, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvan, F.T.; Cunquero, M.; Masvidal-Codina, E.; Walston, S.T.; Marsal, M.; de la Cruz, J.M.; Viana, D.; Nguyen, D.; Degardin, J.; Illa, X.; et al. Graphene-based microelectrodes with bidirectional functionality for next-generation retinal electronic interfaces. Nanoscale Horiz. 2024, 9, 1948–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.E.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Min, B.-K.; Im, M. Retinal degeneration increases inter-trial variabilities of light-evoked spiking activities in ganglion cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 253, 110305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiscella, M.; Farrow, K.; Jones, I.L.; Jäckel, D.; Müller, J.; Frey, U.; Bakkum, D.J.; Hantz, P.; Roska, B.; Hierlemann, A. Recording from defined populations of retinal ganglion cells using a high-density CMOS-integrated microelectrode array with real-time switchable electrode selection. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 211, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibille, J.; Gehr, C.; Benichov, J.I.; Balasubramanian, H.; Teh, K.L.; Lupashina, T.; Vallentin, D.; Kremkow, J. High-density electrode recordings reveal strong and specific connections between retinal ganglion cells and midbrain neurons. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Sun, S.; Luo, J.; Wu, Y.; Cai, X. Exploring retinal ganglion cells encoding to multi-modal stimulation using 3D microelectrodes arrays. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1245082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Fu, T.-M.; Qiao, M.; Viveros, R.D.; Yang, X.; Zhou, T.; Lee, J.M.; Park, H.-G.; Sanes, J.R.; Lieber, C.M. A method for single-neuron chronic recording from the retina in awake mice. Science 2018, 360, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.M.; Shekhar, K.; Whitney, I.E.; Jacobi, A.; Benhar, I.; Hong, G.; Yan, W.; Adiconis, X.; Arnold, M.E.; Lee, J.M.; et al. Single-Cell Profiles of Retinal Ganglion Cells Differing in Resilience to Injury Reveal Neuroprotective Genes. Neuron 2019, 104, 1039–1055.e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickenscheidt, M.; Zeck, G. Action potentials in retinal ganglion cells are initiated at the site of maximal curvature of the extracellular potential. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 036006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szu-Yu Ho, T.; Rasband, M.N. Maintenance of neuronal polarity. Dev. Neurobiol. 2011, 71, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kole, M.H.; Stuart, G.J. Signal Processing in the Axon Initial Segment. Neuron 2012, 73, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.W.; Rasband, M.N.; Meseguer, V.; Kramer, R.H.; Golding, N.L. Serotonin modulates spike probability in the axon initial segment through HCN channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obien, M.E.J.; Deligkaris, K.; Bullmann, T.; Bakkum, D.J.; Frey, U. Revealing neuronal function through microelectrode array recordings. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Joo, S.; Jung, H.; Hong, N.; Nam, Y. Recent trends in microelectrode array technology for in vitro neural interface platform. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2014, 4, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Shimba, K.; Narumi, T.; Asahina, T.; Kotani, K.; Jimbo, Y. Revealing single-neuron and network-activity interaction by combining high-density microelectrode array and optogenetics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claverol-Tinture, E.; Cabestany, J.; Rosell, X. Multisite Recording of Extracellular Potentials Produced by Microchannel-Confined Neurons In-Vitro. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 54, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibey, R.; Latifi, S.; Mousavi, H.; Pesce, M.; Arab-Tehrany, E.; Blau, A. A multielectrode array microchannel platform reveals both transient and slow changes in axonal conduction velocity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogan, S.F.; Troyk, P.R.; Ehrlich, J.; Plante, T.D. In Vitro Comparison of the Charge-Injection Limits of Activated Iridium Oxide (AIROF) and Platinum-Iridium Microelectrodes. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2005, 52, 1612–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference |

Cell Type(s) Involved | Study Targets | System and Experimental Design | Main Findings | Conclusion/Significance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ju et al., 2007 [27] | RGC-5 cell line RGC-5 cells were differentiated with succinyl concanavalin A | Mitochondrial dysfunction in RGC-5 | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized Chamber Duration: 3 days Pressure level (mmHg): 30 |

|

|

|

| Liu et al., 2007 [28] | RGC-5 cell line | Oxidative adduct formation and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) expression in RGC-5 | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized Chamber Duration: 2 h Pressure level (mmHg): 30, 60 and 100 |

|

|

|

| Resta et al., 2007 [39] | Rat RGCs in isolated rat retinas | Viability of RGCs | Pressure type: Dynamic (Pulsatile) Setup: Pressurized Chamber (regulated by electronically controlled gas admission) Duration: 1 h Pressure level (mmHg): 50 |

|

|

|

| Sappington et al., 2009 [33] | Primary mice RGCs | The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized Chamber Duration: 48 h Pressure level (mmHg): 70 |

|

|

|

| Osborne et al., 2015 [40] | Primary RGCs in human reina explant Human organotypic retinal cultures (HORCs) from donor eyes were cultured in serum-free DMEM/hamf12. | Stress pathway signaling and RGCs survival | Pressure type: Both Hydrostatic and Dynamic (1/60 Hz, 10–100 mmHg) Setup: Pressurized Chamber with mass flow controllers Duration: 24 h (static pressure)/1 h cyclic pressure Pressure level (mmHg): 60 |

|

|

|

| Wu et al., 2019 [35] | Primary rats RGCs | Biological changes of RGCs (axon and total neurite length, cell body area, dendritic branching, and cell survival) | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Liquid height Duration: 72 h Pressure level (mmHg): 10, 20, 25, 30, 40 and 50 |

|

|

|

| Nafian et al., 2020 [66] | Primary rat RGCs purified from postnatal Wistar rats | Potential effect of neuroprotection of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or a novel BDNF mimetic (RNYK) on RGCs | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized chamber Duration: 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h Pressure level (mmHg): 15 and 33 |

|

|

|

| Reference | Target Cell Type(s) | Study Aims | Experimental Design | Main Findings | Conclusion/Significance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agar et al., 2000 [34] | Neuronal cell lines (B35 and PC12) B35 line is derived from the CNS of rat. | Cultured neuronal lines | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized Chamber Duration: 2 h Pressure level (mmHg): 100 |

| Pressure alone may act as a stimulus for apoptosis in neuronal cell cultures. |

|

| Sappington et al., 2006 [32] | Primary rat RGCs, astrocyte, and microglia | Glia-derived factors, in particular interleukin-6 (IL-6), on RGC survival | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized Chamber Duration:0–48 h Pressure level (mmHg): 30, 70 |

| Increased IL-6 in microglia medium counters not only proapoptotic signals from these cells but also the pressure-induced apoptotic cascade intrinsic to RGCs. |

|

| Mandal et al., 2010 [43] | Primary rat optic nerve astrocytes | Realtionship between calcium responses and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Liquid height Duration: 2 h Pressure level (mmHg): 15 |

|

|

|

| Yu et al., 2011 [38] | Rat retinal Müller cells | Glutamine synthetase (GS) in rat retinal Müller cells | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized cell culture flask Duration: 24 h Pressure level (mmHg): 20, 40, 60, 80 |

|

|

|

| Lei et al., 2011 [29] | DITNC1 cell line, a kind of optic nerve head [ONH] cells DITNC1 cells are obtained from brain diencephalon tissues of 1-day-old rats. | Potential biological changes of ONH cells cultured on a rigid substrate (migration, shape, and α-tubulin architecture in the cells) | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Liquid height Duration: 48/72 h Pressure level (mmHg): 7.4 |

|

|

|

| Madeira et al., 2015 [30] | Microglia and RGCs in rat retinal organotypic cultures | The ability of A2AR blockade to control the reactivity of microglia and neuroinflammation as well as RGC loss in retinal organotypic cultures | Pressure type: Hydrostatic Setup: Pressurized Chamber Duration: 4/24 h Pressure level (mmHg): 70 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, T.; Hao, J.; Mak, H.; Peng, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Chan, Y.K. Advancing In Vitro Microfluidic Models for Pressure-Induced Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration: Current Insights and Future Directions from a Biomechanical Perspective. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121368

Gao T, Hao J, Mak H, Peng Z, Wu J, Li Q, Chan YK. Advancing In Vitro Microfluidic Models for Pressure-Induced Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration: Current Insights and Future Directions from a Biomechanical Perspective. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121368

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Tianyi, Junhao Hao, Heather Mak, Zhiting Peng, Jing Wu, Qinyu Li, and Yau Kei Chan. 2025. "Advancing In Vitro Microfluidic Models for Pressure-Induced Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration: Current Insights and Future Directions from a Biomechanical Perspective" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121368

APA StyleGao, T., Hao, J., Mak, H., Peng, Z., Wu, J., Li, Q., & Chan, Y. K. (2025). Advancing In Vitro Microfluidic Models for Pressure-Induced Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration: Current Insights and Future Directions from a Biomechanical Perspective. Micromachines, 16(12), 1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121368