Progress in Circulating Tumor Cell Research Using Microfluidic Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Trends in Circulating Tumor Cell (CTC) Research

2.1. Positive Enrichment of CTCs Using Antigen-Antibody Reaction

2.2. Positive Enrichment of CTCs Based on Size

2.3. Negative Enrichment of CTCs

2.4. Integration of Enrichment Methods

3. Single CTC Analysis Using Microfluidic Devices

4. Critical Concerns

4.1. Advantages of CTC Research Compared with That Using Various Circulating Biomarkers

4.2. Commercialization of Microfluidic-Based CTC Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vilsmaier, T.; Rack, B.; Janni, W.; Jeschke, U.; Weissenbacher, T.; SUCCESS Study Group. Angiogenic cytokines and their influence on circulating tumour cells in sera of patients with the primary diagnosis of breast cancer before treatment. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Bardia, A.; Wittner, B.; Stott, S.L.; Smas, M.E.; Ting, D.T.; Isakoff, S.J.; Ciciliano, J.C.; Wells, M.N.; Shah, A.M.; et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science 2013, 339, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.C.; Doyle, G.V.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Significance of circulating tumor cells detected by the CellSearch system in patients with metastatic breast colorectal and prostate cancer. J. Oncol. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Huang, P.H.; Xie, Y.; Mai, J.D.; Wang, L.; Nguyen, N.T.; Huang, T.J. Rare cell isolation and analysis in microfluidics. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertler, R.; Rosenberg, R.; Fuehrer, K.; Dahm, M.; Nekarda, H.; Siewert, J.R. Detection of circulating tumor cells in blood using an optimized density gradient centrifugation. In Molecular Staging of Cancer; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; pp. 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Vona, G.; Sabile, A.; Louha, M.; Sitruk, V.; Romana, S.; Schütze, K.; Capron, F.; Franco, D.; Pazzagli, M.; Vekemans, M. Isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells: A new method for the immunomorphological and molecular characterization of circulating tumor cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.J.; Lakshmi, R.L.; Chen, P.; Lim, W.-T.; Yobas, L.; Lim, C.T. Versatile label free biochip for the detection of circulating tumor cells from peripheral blood in cancer patients. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thege, F.I.; Lannin, T.B.; Saha, T.N.; Tsai, S.; Kochman, M.L.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Rhim, A.D.; Kirby, B.J. Microfluidic immunocapture of circulating pancreatic cells using parallel EpCAM and MUC1 capture: Characterization, optimization and downstream analysis. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 1175–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, T.R. A case of cancer in which cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after death. Aust. Med. J. 1869, 14, 146–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Xiao, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, L. Prognostic role of circulating tumor cells and disseminated tumor cells in patients with prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 5551–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorges, T.M.; Tinhofer, I.; Drosch, M.; Röse, L.; Zollner, T.M.; Krahn, T.; von Ahsen, O. Circulating tumour cells escape from EpCAM-based detection due to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, A.F.; Groom, A.C.; MacDonald, I.C. Metastasis: Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, K.A.; Jung, H.I. Advances and critical concerns with the microfluidic enrichments of circulating tumor cells. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrinucci, D.; Bethel, K.; Lazar, D.; Fisher, J.; Huynh, E.; Clark, P.; Bruce, R.; Nieva, J.; Kuhn, P. Cytomorphology of circulating colorectal tumor cells: A small case series. J. Oncol. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lewis, M.T.; Huang, J.; Gutierrez, C.; Osborne, C.K.; Wu, M.-F.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Pavlick, A.; Zhang, X.; Chamness, G.C.; et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, K.A.; Lee, T.Y.; Jung, H.I. Negative enrichment of circulating tumor cells using a geometrically activated surface interaction chip. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 4439–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.Y.; Hyun, K.A.; Jung, H.I. An integrated microfluidic chip for one-step isolation of circulatingtumor cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 238, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kang, Y.T.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, J.; Cho, Y.-H.; Han, S.W. Polyester fabric sheet layers functionalized with graphene oxide for sensitive isolation of circulating tumor cells. Biomaterials 2017, 125, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceto, N.; Bardia, A.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Donaldson, M.C.; Wittner, B.S.; Spencer, J.A.; Yu, M.; Pely, A.; Engstrom, A.; Zhu, H.; et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell 2014, 158, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Wong, K.H.; Khankhel, A.H.; Zeinali, M.; Reategui, E.; Phillips, M.J.; Luo, X.; Aceto, N.; Fachin, F.; Hoang, A.N.; et al. Microfluidic isolation of platelet-covered circulating tumor cells. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 3498–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, E.; Rivera-Báez, L.; Fouladdel, S.; Yoon, H.J.; Guthrie, S.; Wieger, J.; Deol, Y.; Keller, E.; Sahai, V.; Simeone, D.M.; et al. High-throughput microfluidic labyrinth for the label-free isolation of circulating tumor cells. Cell Syst. 2017, 5, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.G.; Abate, M.F.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Yang, C.J. Isolation, detection and antigen based profiling of circulating tumor cells using a size dictated immunocapture chip. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10681–10685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.L.; Huang, W.; Jalal, S.I.; Chan, B.D.; Mahmood, A.; Shahda, S.; O’Neil, B.H.; Matei, D.E.; Savran, C.A. Circulating tumor cell detection using a parallel flow micro-aperture chip system. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, B.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.; Lee, K.; Kwon, O.; Kang, S.; Kim, Y. Selective isolation of magnetic nanoparticle-mediated heterogeneity subpopulation of circulating tumor cells using magnetic gradient based microfluidic system. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 88, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, B.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.S.; Kang, S.; Lee, Y. Spiral shape microfluidic channel for selective isolating of heterogenic circulating tumor cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 101, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Park, S.; Duffy, S.P.; Matthews, K.; Ang, R.R.; Todenhöfer, T.; Abdi, H.; Azad, A.; Bazov, J.; Chi, K.N.; et al. Size and deformability based separation of circulating tumor cells from castrate resistant prostate cancer patients using resettable cell traps. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 2278–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, K.A.; Koo, G.B.; Han, H.; Sohn, J.; Choi, W.; Kim, S.I.; Jung, H.I.; Kim, Y.S. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition leads to loss of EpCAM and different physical properties in circulating tumor cells from metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 24677–24687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renier, C.; Pao, E.; Che, J.; Liu, H.E.; Lemaire, C.A.; Matsumoto, M.; Tribouler, M.; Srivinas, S.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Rettig, M.; et al. Label-free isolation of prostate circulating tumor cells using Vortex microfluidic technology. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Yuan, H.; Jing, F.; Wu, S.; Zhou, H.; Mao, H.; Jin, Q.; Zhao, J.; Cong, H.; Jia, C. Analysis of circulating tumor cells from lung cancer patients with multiple biomarkers using high-performance size-based microfluidic chip. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 12917–12928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, S.H.; Edd, J.; Haber, D.A.; Maheswaran, S.; Stott, S.L.; Toner, M. Clusters of circulating tumor cells: A biophysical and technological perspective. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 3, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarioglu, A.F.; Aceto, N.; Kojic, N.; Donaldson, M.C.; Zeinali, M.; Hamza, B.; Engstrom, A.; Zhu, H.; Sundaresan, T.K.; Miyamoto, D.T.; et al. A microfluidic device for label-free, physical capture of circulating tumor cell clusters. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; McFaul, S.M.; Duffy, S.P.; Deng, X.; Tavassoli, P.; Black, P.C.; Ma, H. Technologies for label-free separation of circulating tumor cells: From historical foundations to recent developments. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollier, E.; Go, D.E.; Che, J.; Gossett, D.R.; O’Byrne, S.; Weaver, W.M.; Kummer, N.; Rettig, M.; Goldman, J.; Nickols, N.; et al. Size-selective collection of circulating tumor cells using Vortex technology. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo, D. Inertial microfluidics. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 3038–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Tian, C.; Li, T.; Xu, J.; Chen, S.W.; Tu, Q.; Yuan, M.S.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Spiral microchannel with ordered micro-obstacles for continuous and highly-efficient particle separation. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 3578–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, K.-A.; Lee, T.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, H.-I. Two-stage microfluidic chip for selective isolation of circulating tumor cells (CTCs). Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 67, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, J.; Kang, Y.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Cho, Y.H.; Chang, H.J.; Kim, H.; Moon, B.I.; Kim, H.G. Dual-patterned immunofiltration (DIF) device for the rapid efficient negative selection of heterogeneous circulating tumor cells. Lab Chip 2016, 24, 4759–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushing, K.; Undvall, E.; Ceder, Y.; Lilja, H.; Laurell, T. Reducing WBC background in cancer cell separation products by negative acoustic contrast particle immuno-acoustophoresis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1000, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fachin, F.; Spuhler, P.; Martel-Foley, J.M.; Edd, J.F.; Barber, T.A.; Walsh, J.; Karabacak, M.; Pai, V.; Yu, M.; Smith, K.; et al. Monolithic chip for high-throughput blood cell depletion to sort rare circulating tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Zhao, H.; Shu, W.; Tian, J.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, E.; Slamon, D.; Hou, D.; et al. An integrated microfluidic device for rapid and high-sensitivity analysis of circulating tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, F.D.; Turetta, M.; Celetti, G.; Piruska, A.; Bulfoni, M.; Piruska, A.; Bulfoni, M.; Cesselli, D.; Huck, W.T.S.; Scoles, G. A method for detecting circulating tumor cells based on the measurement of single-cell metabolism in droplet-based microfluidics. Angew. Chem. 2016, 55, 8581–8584. [Google Scholar]

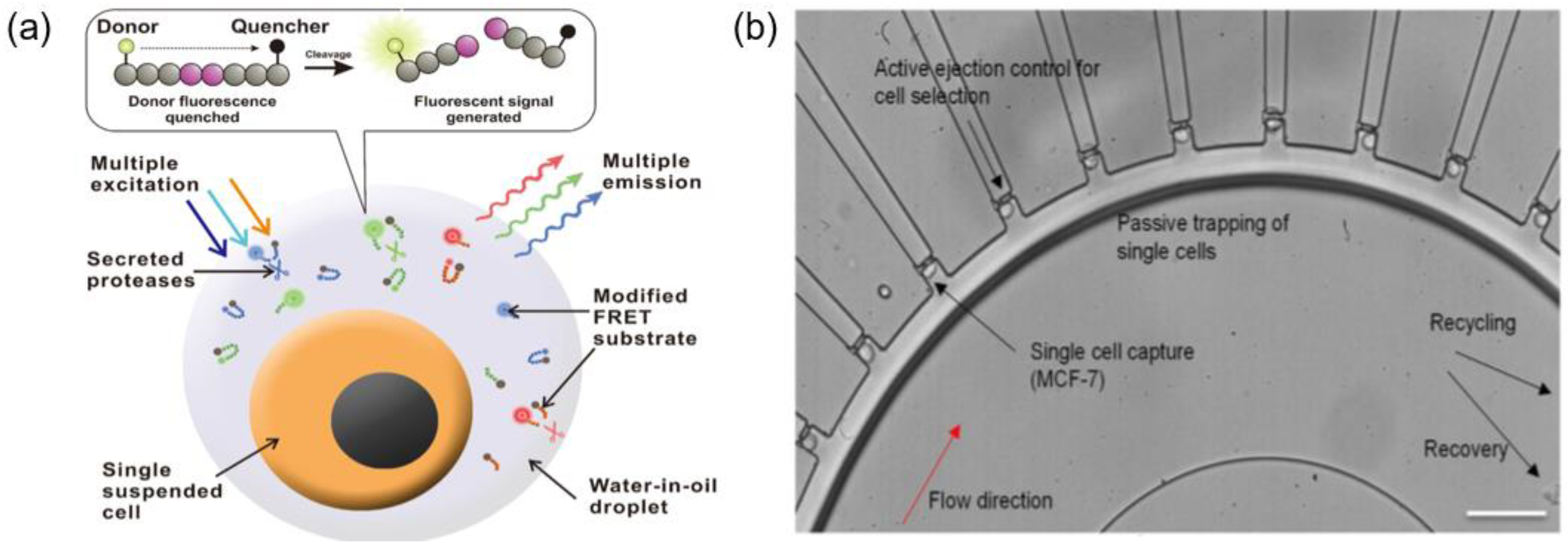

- Ng, E.X.; Miller, M.A.; Jing, T.; Chen, C. Single cell multiplexed assay for proteolytic activity using droplet microfluidics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 81, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, T.; Tan, S.J.; Lim, C.L.; Lau, D.P.X.; Chua, Y.W.; Kirsna, S.S.; Lyer, G.; Tan, G.S.; Lim, T.K.H.; Tan, D.S.W.; et al. Microfluidic enrichment for the single cell analysis of circulating tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.T.; Wittner, B.S.; Ligorio, M.; Jordan, N.V.; Shah, A.M.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Aceto, N.; Bersani, F.; Brannigan, B.W.; Xega, K.; et al. Single-Cell RNA sequencing identifies extracellular matrix gene expression by Pancreatic circulating tumor cells. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1905–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Real-time liquid biopsy in cancer patients: Fact or fiction? Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 6384–6388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisitkun, T.; Shen, R.F.; Knepper, M.A. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 13368–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotara, A.; Markou, A.; Lianidou, E.S.; Patrinos, G.P.; Katsila, T. Exosomes: A cancer theranostics road map. Public Health Genom. 2017, 20, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharaziha, P.; Ceder, S.; Li, Q.; Panaretakis, T. Tumor cell-derived exosomes: A message in a bottle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1826, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Naranjo, J.C.; Wu, H.J.; Ugaz, V.M. Microfluidics for exosome isolation and analysis: Enabling liquid biopsy for personalized medicine. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 3558–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, T.L. Tumor-derived exosomes and their role in cancer progression. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2016, 74, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwarzenbach, H.; Hoon, D.S.; Pantel, K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Clinical applications of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA as liquid biopsy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, R.E.; Drew, H.R.; Conner, B.N.; Wing, R.M.; Fratini, A.V.; Kopka, M.L. The anatomy of A-, B-, and Z-DNA. Science 1982, 216, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ershova, E.; Sergeeva, V.; Klimenko, M.; Avetisova, K.; Klimenko, P.; Kostyuk, E.; Veiko, N.; Veiko, R.; Izevskaya, V.; Kutsev, S.; et al. Circulating cell-free DNA concentration and DNase I activity of peripheral blood plasma change in case of pregnancy with intrauterine growth restriction compared to normal pregnancy. Biomed. Rep. 2017, 7, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Olmo, D.; García Olmo, D.C.; Ontañon, J.; Martínez, E.; Vallejo, M. Tumor DNA circulating in the plasma might play a role in metastasis. The hypothesis of the genometastasis. Histol. Histopathol. 1999, 14, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spindler, K.L.G. Methodological, biological and clinical aspects of circulating free DNA in metastatic colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, M.; Amant, F.; Biankin, A.V.; Budinská, E.; Byrne, A.T.; Caldas, C.; Clarke, R.B.; de Jong, S.; Jonkers, J.; Mælandsmo, G.M.; et al. Patient-derived Xenograft models: An emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Circulating Biomarkers | Features | Isolation Techniques | Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTC |

|

|

| -- |

| Exosome |

|

|

| [46,47,48,49] |

| cfDNA |

|

|

| [51,52,53] |

| Company (Country) | Product (Chip) | Highlights | Revenue * | Year Founded | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angel plc (UK) | ParsortixTM system |

| $0.64 million | 2003 | http://www.angleplc.com |

| ApoCell, Inc. (USA) | ApoStreamTM |

| $6.27 million | 2004 | http://www.apocell.com |

| Biocept, Inc. (US) | Target Selector™ platform (CEE microfluidic chip) |

| $3.22 million | 1997 | https://biocept.com |

| Biofluidica, Inc. (USA) | BioFluidica’s CTC System |

| $0.29 million | 2012 | http://www.biofluidica.com |

| Celsee diagnostics (USA) | Celsee PREP 400, Celsee ANALYZER |

| -- | 2011 | https://www.celsee.com |

| Clearbridge Biomedics (Singapore) | ClearCell® FX1 system (CTChip® FR) |

| $0.57 million | 2009 | http://www.clearbridgebiomedics.com |

| Cynvenio Biosystems, Inc. (USA) | LiquidBiopsy® Platform (ClearID® Clinical Testing) |

| -- | https://www.cynvenio.com | |

| Fluxion Bioscience, Inc. (USA) | IsoFlux CTC system, IsoFlux Cytation Imager |

| -- | https://liquidbiopsy.fluxionbio.com/ | |

| Menarini Silicon Biosystem (USA) | DEPArray™ |

| $5.58 million | 1976 | http://www.siliconbiosystems.com |

| Vortex Bioscience | VTX-1 |

| -- | 2010 | https://vortexbiosciences.com |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gwak, H.; Kim, J.; Kashefi-Kheyrabadi, L.; Kwak, B.; Hyun, K.-A.; Jung, H.-I. Progress in Circulating Tumor Cell Research Using Microfluidic Devices. Micromachines 2018, 9, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi9070353

Gwak H, Kim J, Kashefi-Kheyrabadi L, Kwak B, Hyun K-A, Jung H-I. Progress in Circulating Tumor Cell Research Using Microfluidic Devices. Micromachines. 2018; 9(7):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi9070353

Chicago/Turabian StyleGwak, Hogyeong, Junmoo Kim, Leila Kashefi-Kheyrabadi, Bongseop Kwak, Kyung-A Hyun, and Hyo-Il Jung. 2018. "Progress in Circulating Tumor Cell Research Using Microfluidic Devices" Micromachines 9, no. 7: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi9070353

APA StyleGwak, H., Kim, J., Kashefi-Kheyrabadi, L., Kwak, B., Hyun, K.-A., & Jung, H.-I. (2018). Progress in Circulating Tumor Cell Research Using Microfluidic Devices. Micromachines, 9(7), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi9070353