Design and Simulation Analysis of a Temperature Control System for Real-Time Quantitative PCR Instruments Based on Key Hot Air Circulation and Temperature Field Regulation Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Technical Solution and Structural Layout of the Temperature Control System

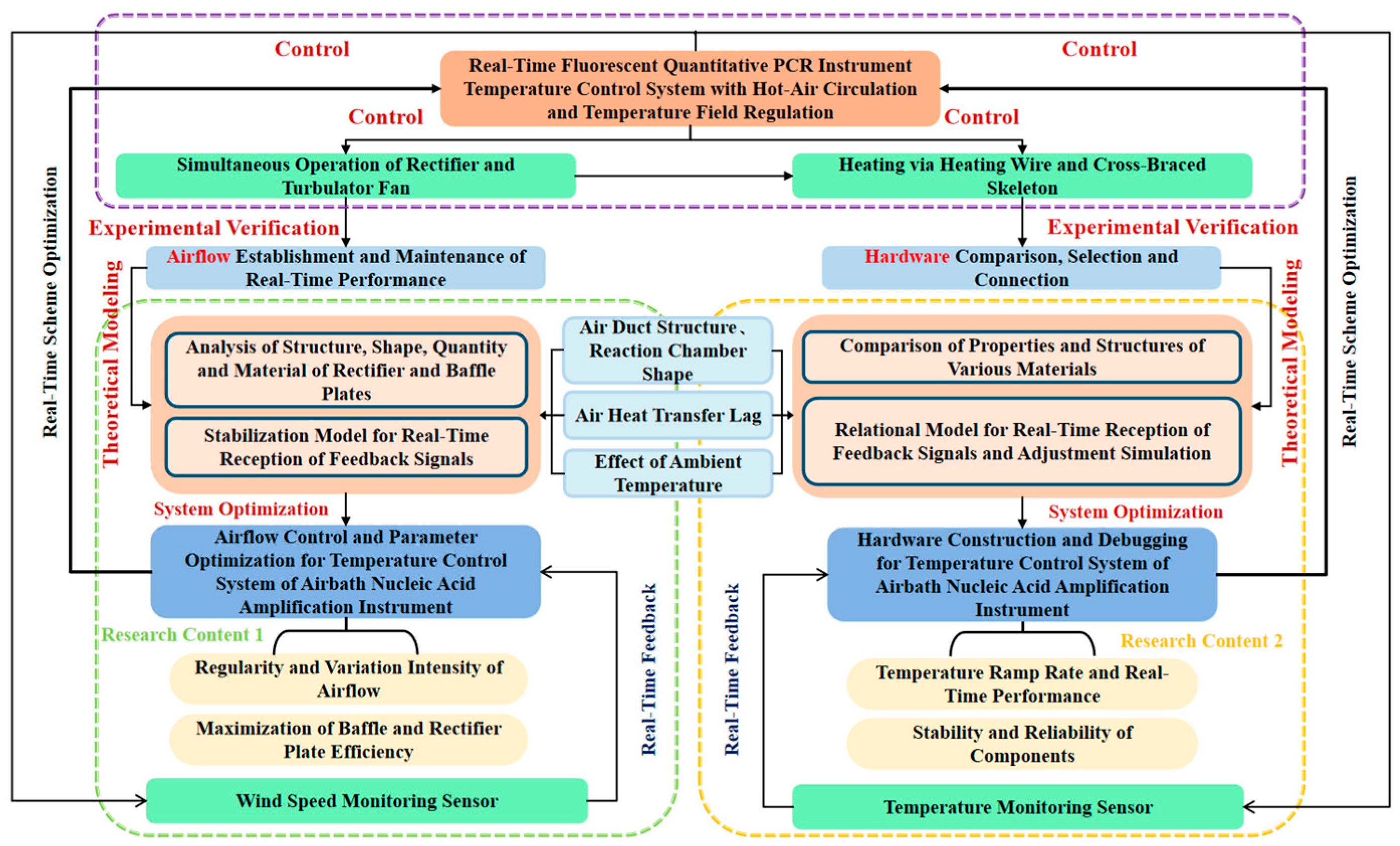

2.1. Research Framework for the Temperature Control System

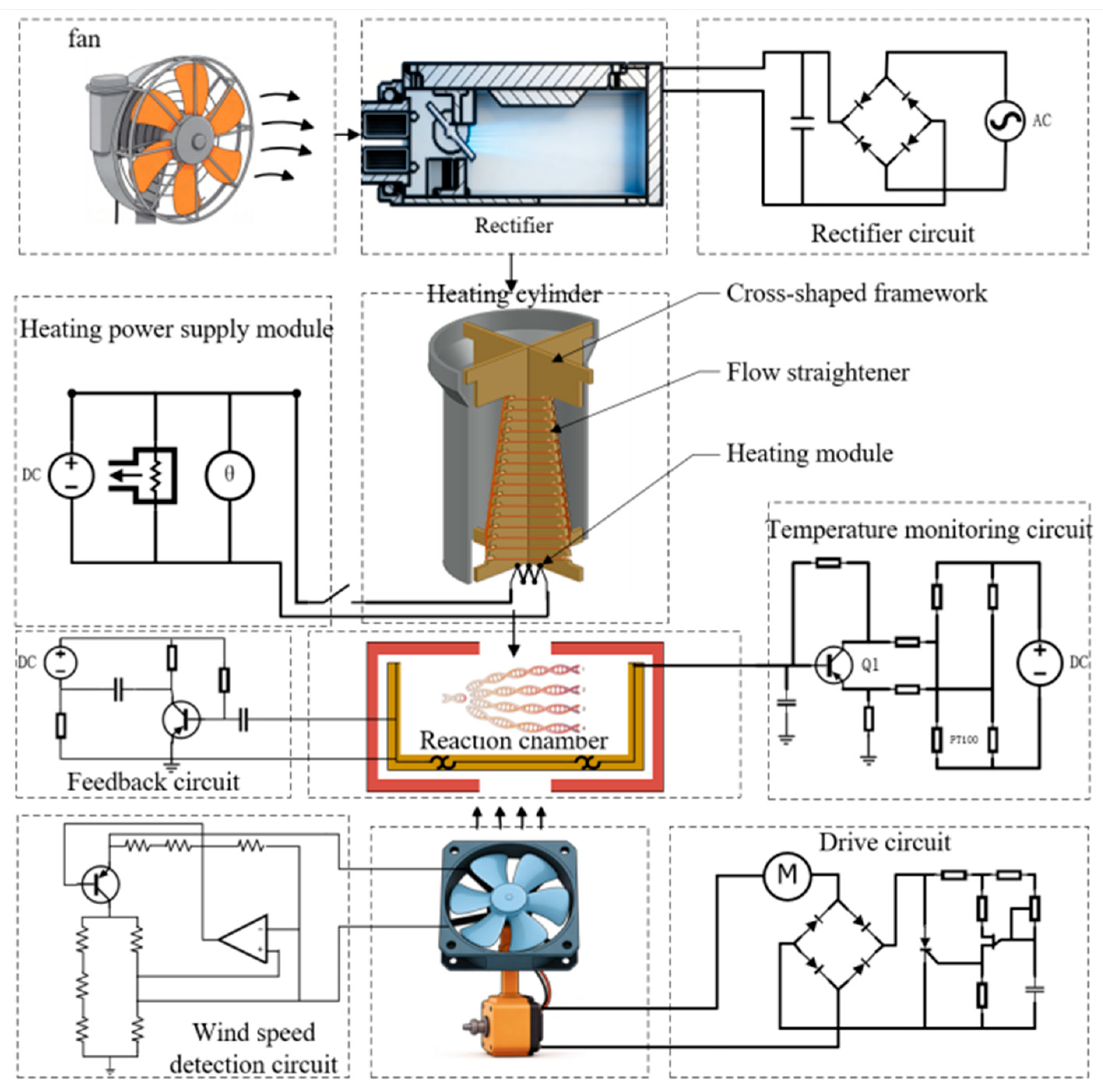

2.2. Technical Solution for the Temperature Control System

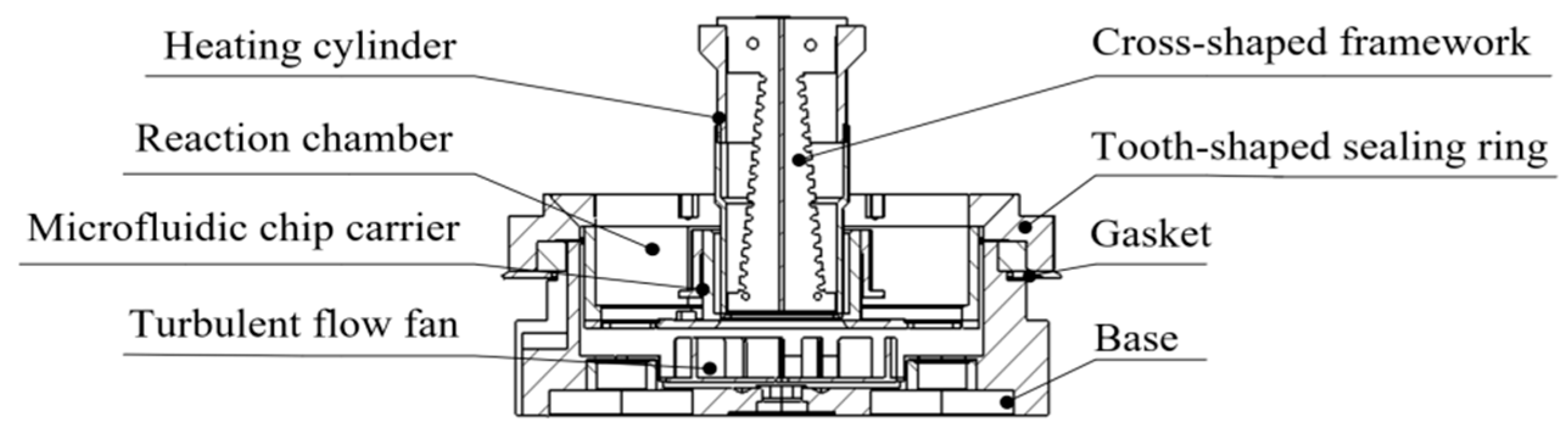

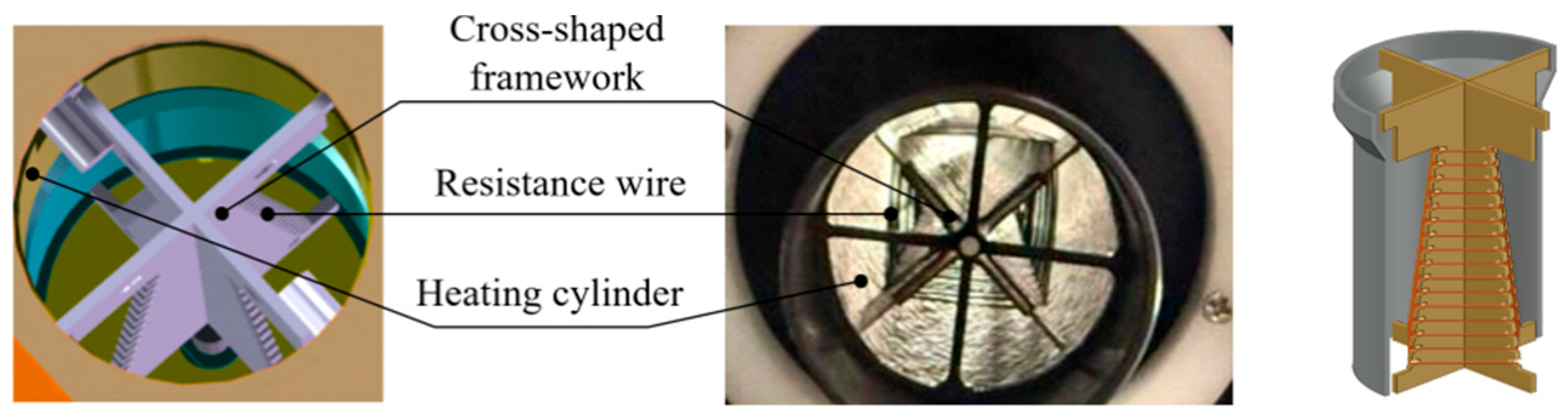

2.3. Structural Layout of the Temperature Control System

2.4. Overall Structure and Microfluidic Chip Layout

3. Reliability Analysis of the Temperature Control System

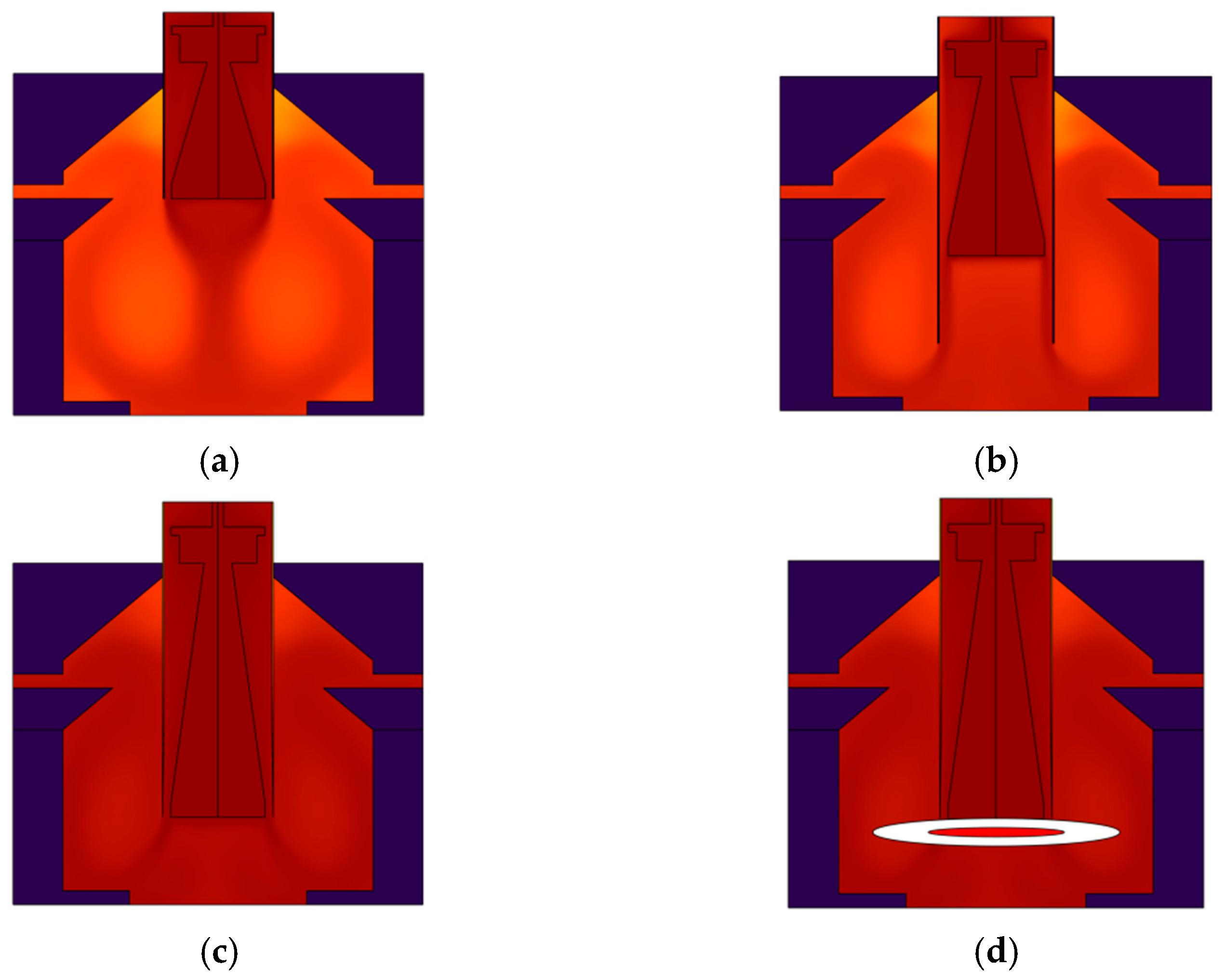

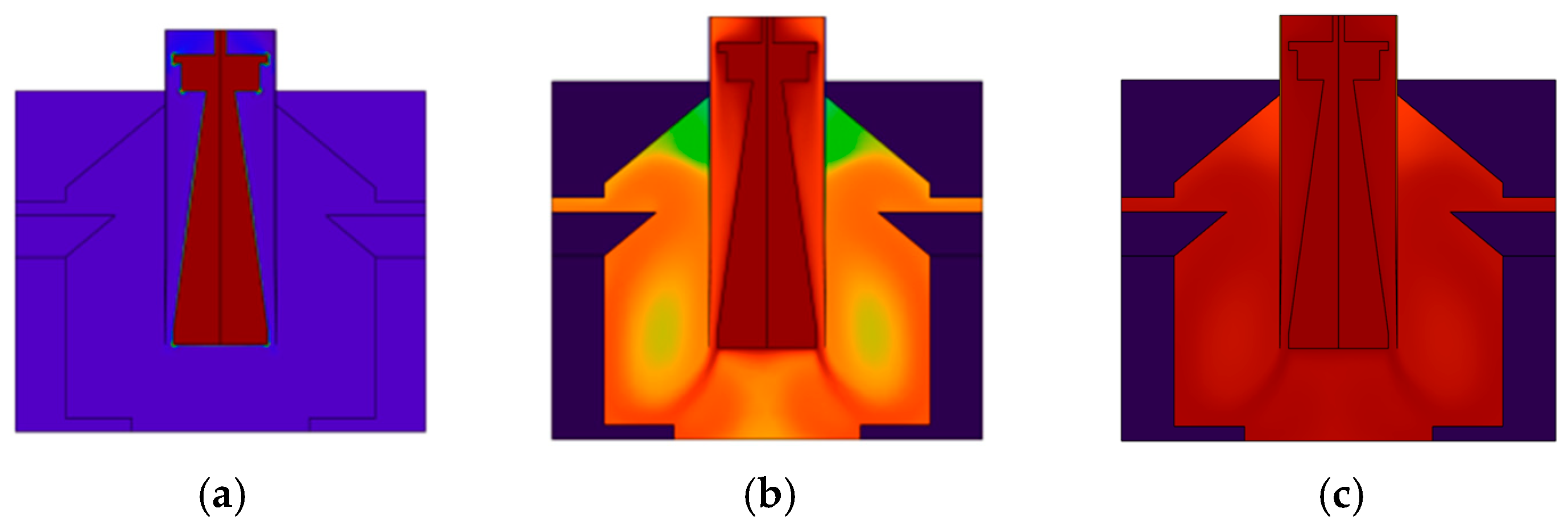

3.1. Temperature Control System

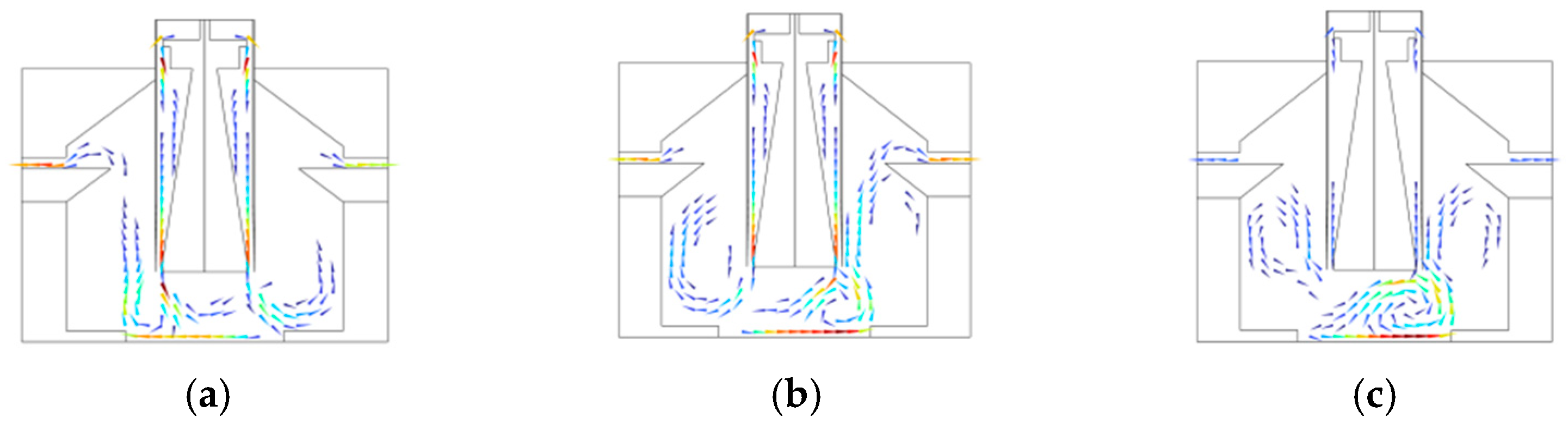

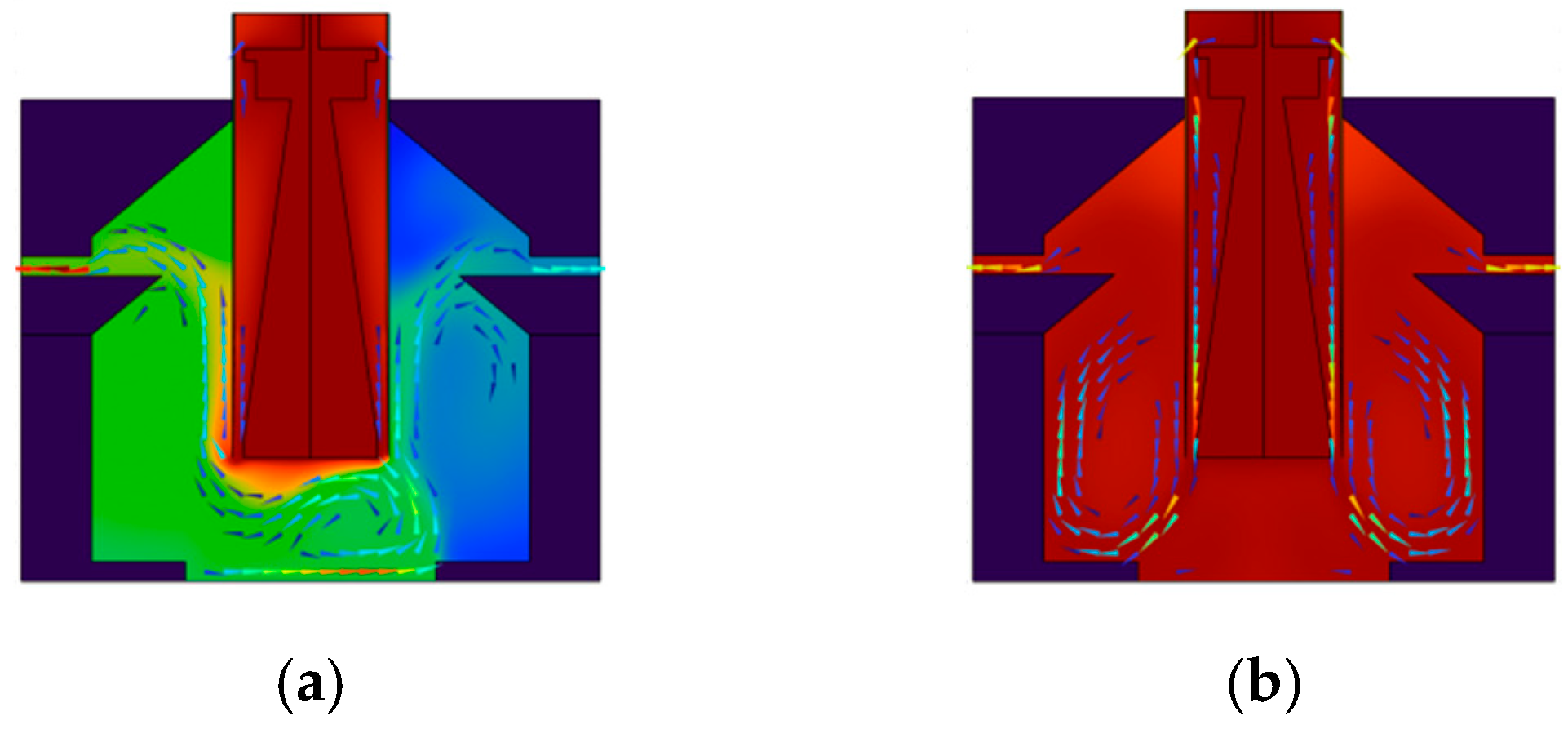

3.2. Airflow Rectification System

4. Harmonic Response Analysis of the Temperature Control System

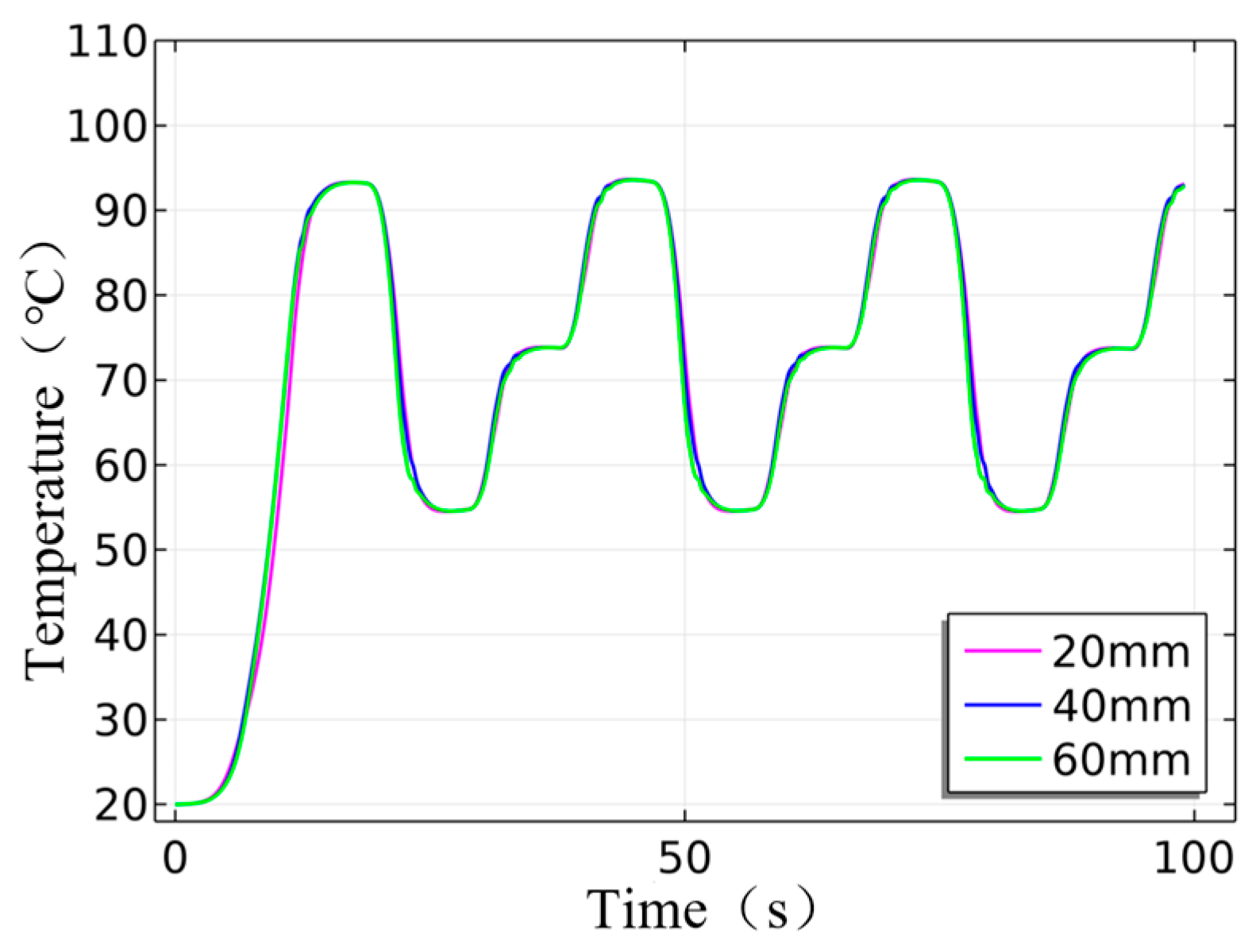

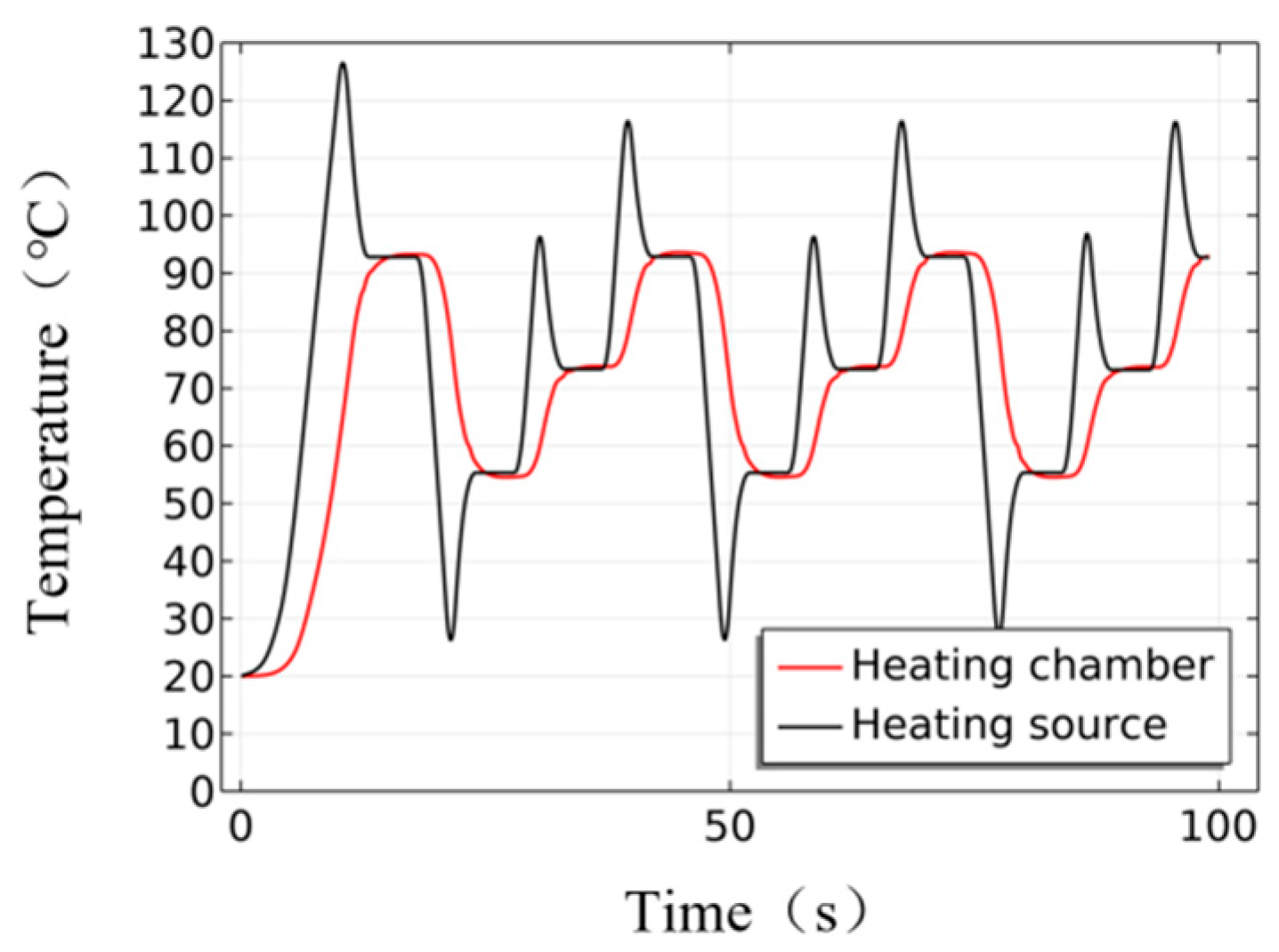

4.1. Thermal Performance of PCR Instruments

4.2. Rectification Performance of PCR Instruments

5. Reliability Testing of the Temperature Control System

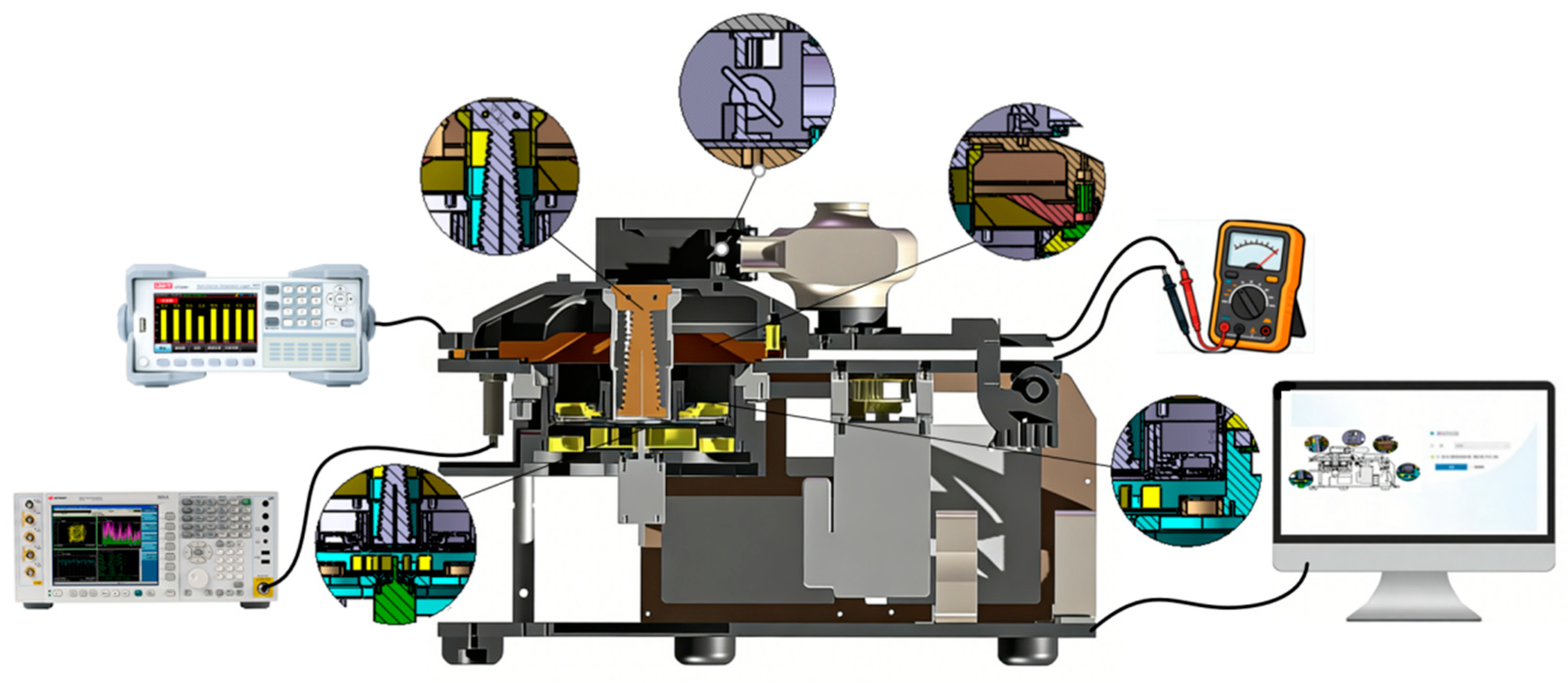

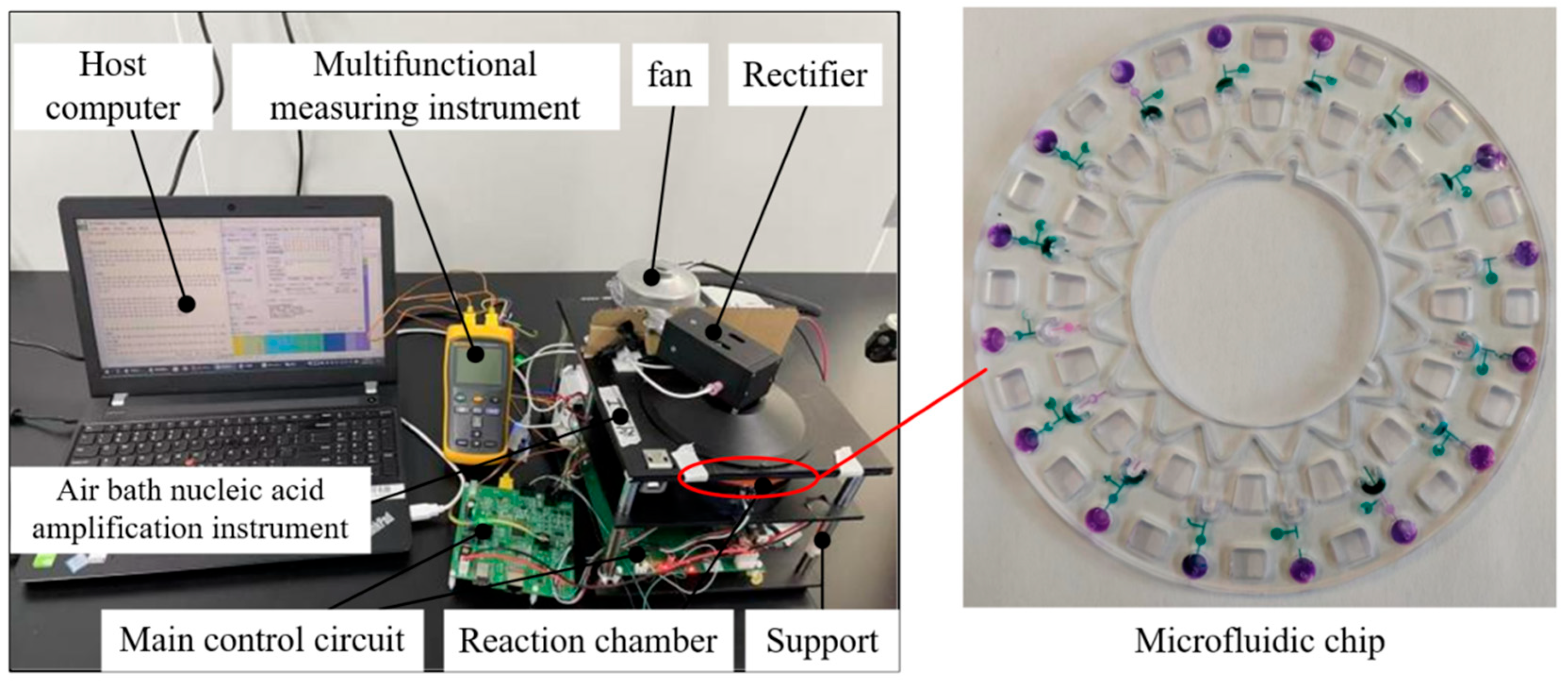

5.1. Experimental Setup

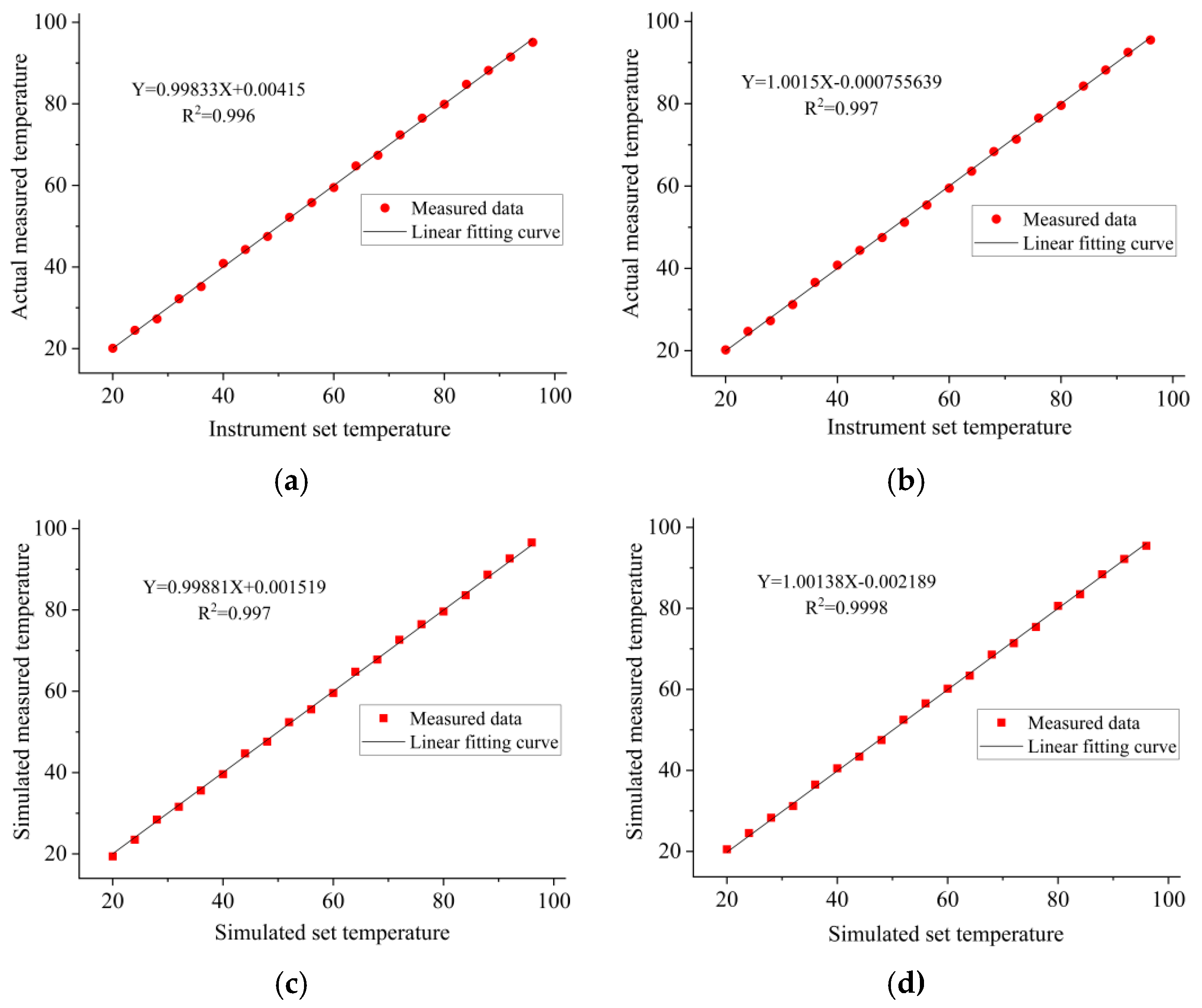

5.2. Reproducibility Analysis

5.3. Temperature Uniformity Analysis

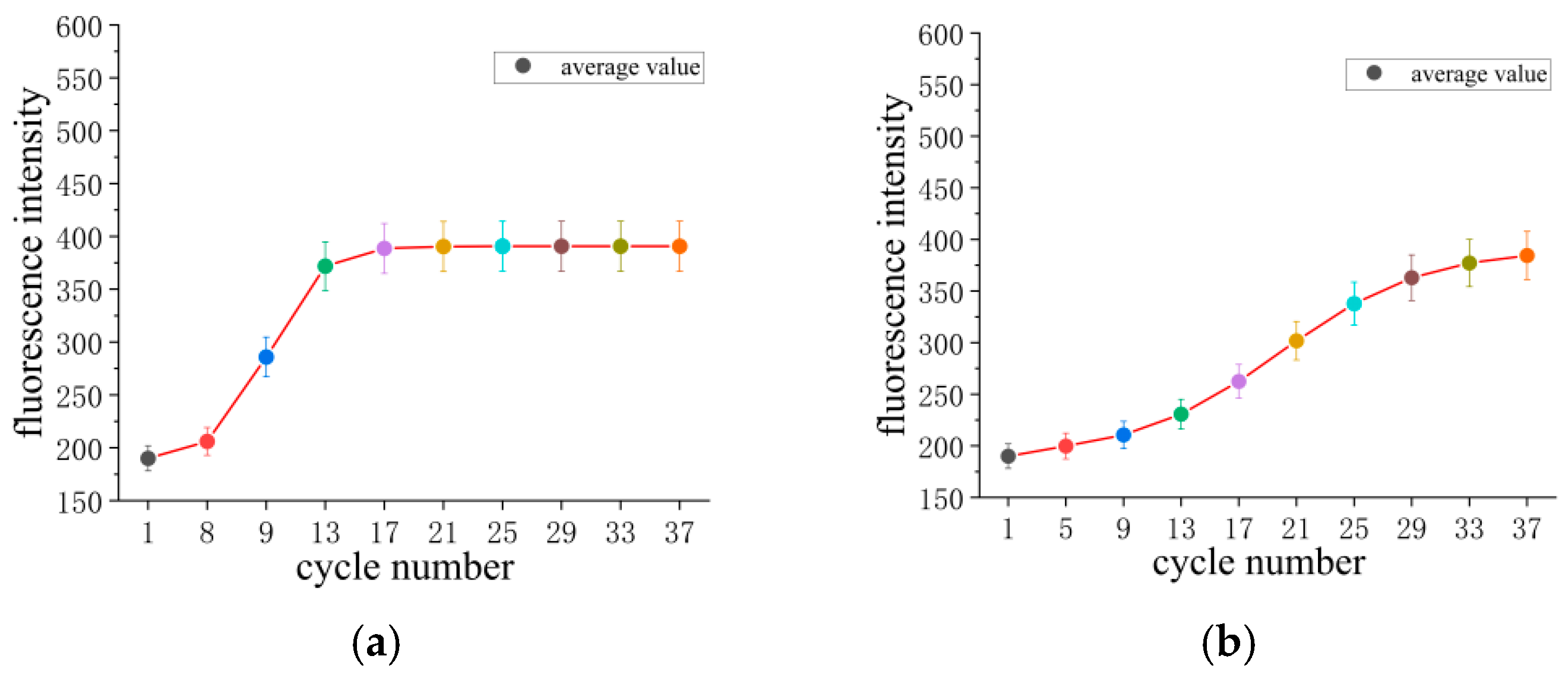

5.4. Reliability Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeom, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Ahn, S.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y.; Koo, C. A Thermocycler Using a Chip Resistor Heater and a Glass Microchip for a Portable and Rapid Microchip-Based PCR Device. Micromachines 2022, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, M.; Kang, R.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Jiang, B. A quick thermal response digital acoustofluidic system for rapid on-chip PCR. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 290, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Si, H.; Jing, F.; Sun, P.; Zhao, D.; Wu, D. A Double-Deck Self-Digitization Microfluidic Chip for Digital PCR. Micromachines 2020, 11, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, C.; Taylor, D.; Linacre, A. PCR in Forensic Science: A Critical Review. Genes 2024, 15, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Laššáková, S.; Korabečná, M.; Neužil, P. PCR Past, Present and Future. BioTechniques 2020, 69, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Liu, X.; Xiao, X. Physical Simulation-Based Calibration for Quantitative Real-Time PCR. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Rokshana, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, F. Near-Infrared Responsive Droplet for Digital PCR. Small 2022, 18, e2107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashouf, H.; Talebjedi, B.; Tasnim, N.; Tan, M.; Alousi, S.; Pakpour, S.; Hoorfar, M. Development of a disposable and easy-to-fabricate microfluidic PCR device for DNA amplification. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2023, 189, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Yu, C.; Li, S.; Wei, C.; Dai, S.; Li, H.; Li, J. Microfluidics Temperature Compensating and Monitoring Based on Liquid Metal Heat Transfer. Micromachines 2022, 13, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tong, X.; Li, W.; Liang, L.; Liu, B.; Chen, C. Simulation of Rapid Thermal Cycle for Ultra-Fast PCR. Sensors 2022, 22, 9990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Tong, J.; Li, J.; Shao, G.; Xie, B.; Zhuang, J.; Bi, G.; Mu, Y. A portable, high-throughput real-time quantitative PCR device for point-of-care testing. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 674, 115200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Peng, C.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wu, W. Portable Heating System Based on a Liquid Metal Bath for Rapid PCR. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 26165–26173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Zhou, W.; Cui, J.; Shen, Z.; Wei, Q.; Chu, X. Experimental study on the heating/cooling and temperature uniformity performance of the microchannel temperature control device for nucleic acid PCR amplification reaction of COVID-19. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 226, 120342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, Z.; Wu, W. Construction of Very Low-Cost Loop Polymerase Chain Reaction System Based on Proportional-Integral-Derivative Temperature Control Optimization Algorithm and Its Application in Gene Detection. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 46003–46011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, L.; Yu, Y.; Meng, X. Microdroplet PCR in Microfluidic Chip Based on Constant Pressure Regulation. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, E.; Sun, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, J.; Feng, S.; Liu, B. Implementation of Rapid Nucleic Acid Amplification Based on the Super Large Thermoelectric Cooler Rapid Temperature Rise and Fall Heating Module. Biosensors 2024, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, L.; Shen, Y.; Gong, P.; Zhang, H.; Meng, X.; Yu, Y. Constant Pressure-Regulated Microdroplet Polymerase Chain Reaction in Microfluid Chips: A Methodological Study. Micromachines 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos-Reis-Delgado, A.A.; Carmona-Dominguez, A.; Sosa-Avalos, G.; Jimenez-Saaib, I.H.; Villegas-Cantu, K.E.; Gallo-Villanueva, R.C.; Perez-Gonzalez, V.H. Recent advances and challenges in temperature monitoring and control in microfluidic devices. Electrophoresis 2022, 44, 268–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, X.; Su, H.; Li, S.; Chen, Y. Temperature Control of a Droplet Heated by an Infrared Laser for PCR Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 14341–14353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, G.A.; Abdel-Mawgood, A.L.; Abouelsoud, A.A.; Mohamed, H.; Umezu, S.; El-Bab, A.M.F. New cost effective design of PCR heating cycler system using Peltier plate without the conventional heating block. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 3259–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishbin, E.; Eghbal, M.; Navidbakhsh, M.; Zandi, M. Localized air-mediated heating method for isothermal and rapid thermal processing on lab-on-a-disk platforms. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 294, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, J.; Wang, S.; Luo, G.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. PCR virtual temperature sensor design based on system modeling and identification. Measurement 2025, 240, 115605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fang, Y.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, M.; Xing, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, N. Temperature control algorithm for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) instrumentation based upon improved hybrid fuzzy proportional integral derivative (PID) control. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2023, 51, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, Q.; Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Lou, K.; Liu, Y.; Wen, W. A Rapid Digital PCR System with a Pressurized Thermal Cycler. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Cui, C. Temperature control technology for PCR. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electron. Netw. Devices Fields 2024, 37, e3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.-Q.; Huang, S.-L.; Xi, B.-C.; Gong, X.-L.; Ji, J.-H.; Hu, Y.; Ding, Y.-J.; Zhang, D.-X.; Ge, S.-X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Ultrafast Microfluidic PCR Thermocycler for Nucleic Acid Amplification. Micromachines 2023, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaňová, M.; Wang, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lednický, T.; Korabečná, M.; Neužil, P. Temperature non-uniformity detection on dPCR chips and temperature sensor calibration. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; An, Y.; Xi, B.; Gong, X.; Chen, Z.; Shao, S.; Ge, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Xia, N. Ultra-fast, sensitive and low-cost real-time PCR system for nucleic acid detection. Lab A Chip 2023, 23, 2611–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Chang, C.; Zhao, X.; Yong, H.; Ke, X.; Wu, Z. A Thermal Cycler Based on Magnetic Induction Heating and Anti-Freezing Water Cooling for Rapid PCR. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument Type | Up Ramp (°C/s) | Down Ramp (°C/s) | Steady-State Temperature Deviation (±°C) | Single Cycle Duration (s) | Total Duration for 35 Cycles (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid metal bath | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.3 | 82 ± 3 | 47.8 ± 1.2 |

| Peltier-cooled air bath | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.4 | 75 ± 2 | 43.8 ± 0.8 |

| Air bath | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 13.5 ± 0.1 | 0.1 | 28 ± 2 | 16.3 ± 0.6 |

| Structural Configuration | Temperature Uniformity Inside Heating Chamber (°C) | Time Taken for Heating Up to 95 °C (s) | Time Taken for Cooling Down to 55 °C (s) | Sample Amplification Efficiency After 35 Cycles (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme A (Equal height short cylinder) | 1.2 | 17.3 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 92.5 ± 1.3 |

| Scheme B (Unequal height) | 1.8 | 16 ± 2 | 10.3 ± 1 | 88.3 ± 1.5 |

| Scheme C (Equal height long cylinder) | 0.1 | 14 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 98.9 ± 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Shi, L.; Meng, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y. Design and Simulation Analysis of a Temperature Control System for Real-Time Quantitative PCR Instruments Based on Key Hot Air Circulation and Temperature Field Regulation Technologies. Micromachines 2026, 17, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020169

Wang Z, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Shi C, Zhao Z, Chen Q, Shi L, Meng X, Zhang H, Yu Y. Design and Simulation Analysis of a Temperature Control System for Real-Time Quantitative PCR Instruments Based on Key Hot Air Circulation and Temperature Field Regulation Technologies. Micromachines. 2026; 17(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhe, Yue Zhao, Yan Wang, Chunxiang Shi, Zizhao Zhao, Qimeng Chen, Lemin Shi, Xiangkai Meng, Hao Zhang, and Yuanhua Yu. 2026. "Design and Simulation Analysis of a Temperature Control System for Real-Time Quantitative PCR Instruments Based on Key Hot Air Circulation and Temperature Field Regulation Technologies" Micromachines 17, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020169

APA StyleWang, Z., Zhao, Y., Wang, Y., Shi, C., Zhao, Z., Chen, Q., Shi, L., Meng, X., Zhang, H., & Yu, Y. (2026). Design and Simulation Analysis of a Temperature Control System for Real-Time Quantitative PCR Instruments Based on Key Hot Air Circulation and Temperature Field Regulation Technologies. Micromachines, 17(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020169