3.1. Orthogonal Experiment

The results of the above orthogonal experiments were analyzed by means of variance (ANOVA), which was used to evaluate the effect of controllable factors on the results of the study by decomposing the total variation into different sources of variation and examining the degree of variation between the different groups. The variation of each controllable factor was evaluated by the extreme variance (Range, R), which was used to determine the degree of influence of different controllable factors on the results of the study. The surface roughness, Sa, of the samples after laser polishing was used as an evaluation index of the quality of laser polishing, and it should be emphasized that the average value of three samples was selected for calculating the evaluation index of each polishing process. The statistical data are shown in

Table 6, and the typical morphology at each process parameter is shown in

Figure 6.

The main effect analysis can determine the optimal level and the combination of optimal levels in the orthogonal experiments, and the results of the main effect analysis for each process parameter of the orthogonal experiments in this paper are shown in

Table 7 and

Figure 7. For the process parameter LPP, the range R1 is 1.74 μm, and the optimal level is 4 (10,400 kW/cm

2); for the process parameter LPS, the range R2 is 1.26, and the optimal level is 3 (800 mm/s); and for the process parameter LPT, the range R3 is 0.67, and the optimal level is 1 (1 time). Thus, the optimum surface roughness Sa can be obtained when the process parameter combination is 4 (10,400 kW/cm

2)

−3 (800 mm/s)

−1 (1 time). Furthermore, by comparing the values of R1, R2, and R3, LPP has the greatest effect on surface roughness, followed by LPS, and LPT has the least effect. Unless otherwise noted, all subsequent studies are conducted using the process parameter combination 4 (10,400 kW/cm

2)

−3 (800 mm/s)

−1 (1 time).

Figure 8 shows the surface roughness of EB-PBF Ti6Al4V after laser polishing using the optimal combination of process parameters 4 (10,400 kW/cm

2)

−3 (800 mm/s)

−1 (1). The morphology of EB-PBF Ti6Al4V after laser polishing is shown in

Figure 6. The surface roughness, Sa, of the material in the area of 337.82 × 282.62 um measured by WLI is 0.26 μm, and that of the material before polishing is 13.18 μm. The surface roughness of the material has been reduced by 98.03% after laser polishing, and at the same time, the SEM images show that the laser-polished area is homogeneous, and that there are no obvious cracks and defects, such as irregular bumps and depressions.

3.2. Laser Polishing Mechanism Based on Molten Pool Dynamics

With the input of laser energy, EB-PBF Ti6Al4V gradually transforms from the solid phase to the liquid and gas phases, and the liquid-phase part of the material flows under surface forces (capillary forces due to spatial curvature difference, thermocapillary forces due to temperature gradient, and recoil pressure due to evaporation) as well as volumetric forces (gravitational and buoyant forces). The distribution of the above three surface forces and laser energy shows a complex non-linear relationship, and the three are coupled in the molten pool flow state during laser polishing over time. Therefore, in order to reveal the influence of process parameters on laser polishing, it is important to investigate the interaction mechanism between laser energy and EB-PBF Ti6Al4V based on molten pool dynamics in conjunction with numerical simulation results.

Figure 9a shows the surface temperature distribution of the material at different moments. It can be seen that the temperature rises sharply when the laser energy is applied to the material. When the processing time reaches 0.1 ms, the highest temperature on the material surface is 3233 K at the center of the laser spot. At this time, the material temperature within the range of nearly 150 μm exceeds the liquidus temperature, forming a molten pool. With time, the temperature gradually increases, and the area exceeding the temperature of the liquid phase line also gradually increases; at the moment of 0.6 ms, the melt pool spreads over the entire material surface, and during the time period of 0.7 ms–0.8 ms, the temperature of the material surface gradually stabilizes at 2000 K due to the movement of the beam, which has already exceeded the processed area.

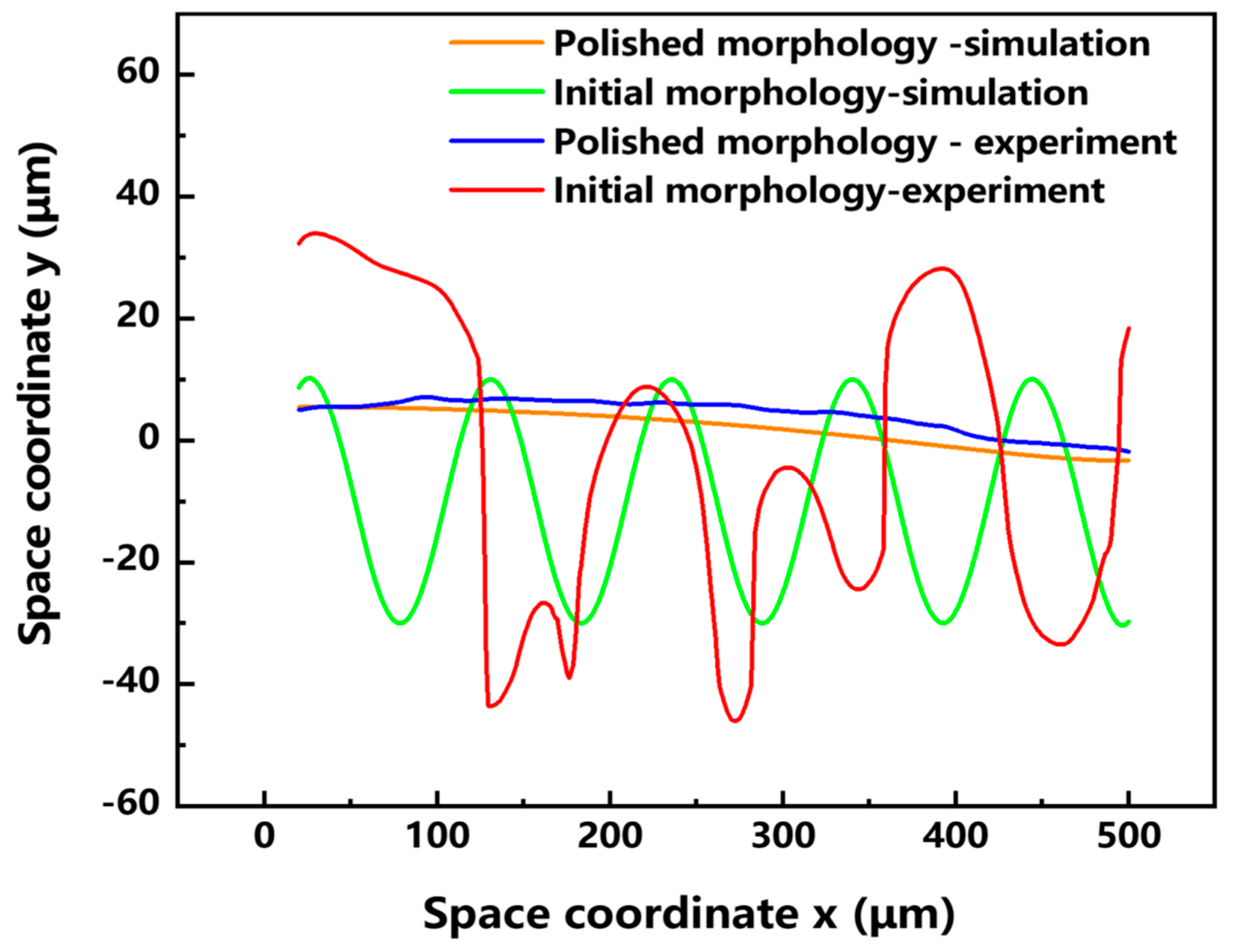

Figure 9b shows the variation of the space curvature of the material at different moments. The value of the space curvature, which describes the degree of curvature of the surface, is used to characterize the roughness of the material morphology, and the larger the space curvature is, the rougher the material surface. As time increases, the space curvature gradually decreases. The space curvature at 0.8 ms is reduced by 95.65% compared to the space curvature at 0 ms, indicating that the roughness of the material has been greatly improved after laser polishing.

To further study the motion of the molten pool during laser polishing, numerical simulation data of the temperature field, velocity field, and phase field were visualized, and the dynamics of the molten pool during laser polishing were studied by combining capillary force, thermocapillary force, and recoil pressure maps at different times.

Figure 10a–f show the evolution of the surface morphology and phase field distribution at 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 ms. The red box displays the velocity field distribution in front of the molten pool, while the green box displays the phase field distribution of the material. In the phase field diagram, the red area represents the liquid phase region and the blue area represents the solid phase region.

Figure 11a–f show the evolution of surface forces at 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 ms, respectively. From the melt pool evolution process, under the action of laser energy, the convex peaks on the original rough surface gradually disappear under the flow of the melt pool, and the original rough surface becomes smooth.

At the 0 ms moment, because the laser energy just acted on the surface of the material, the highest temperature of 306 K (see

Figure 10a) has not yet resulted in a phase transition and has not formed a molten pool; therefore, the material surface morphology has not changed, and, at this time, among the surface forces, the capillary force occupies an absolutely dominant position (see

Figure 11a). At the moment of 0.1 ms, the molten pool gradually appears, and the first bump on the rough surface starts to flatten under the action of the surface force (see

Figure 10b). In the region of 20 < x < 110 μm, a larger temperature gradient gradually arises with the temperature increase, and the thermocapillary force increases in this region with the same dominant role as that of the capillary force on the flow of the molten pool (see

Figure 11b). Since the surface tension of Ti6Al4V due to the negative temperature coefficient of Ti6Al4V, the molten pool moves outward from the center of the laser spot, and the molten material gradually flows from the first peak to the first valley under the action of the thermocapillary force; at this time, the heat generated by the laser has not yet been transferred to other regions, and the surface tension still dominates in the region of 110 < x < 500 μm. At the moment of 0.2 ms, as the temperature continues to rise and the area irradiated by the laser increases (see

Figure 10c), the liquid phase region on the material surface grows to 245 μm, and in the 20 < x < 200 μm region, as the phase transition to the liquid phase has already occurred, the spatial curvature becomes flat under the coupling effect of surface forces; the capillary force is gradually reduced, so that the thermocapillary force in this region is gradually dominated (see

Figure 11c). At the same time, in the 68 < x < 118 μm region, the maximum temperature reaches 3287 K, which has been close to the evaporation temperature of Ti6Al4V (3315 K). Part of the material in this region is removed by evaporation to produce a recoil pressure. At the moment of 0.2 ms, as the temperature continues to rise and the area irradiated by the laser increases (see

Figure 10c), the liquid-phase region on the material surface grows to 245 μm; in the 20 < x < 200 μm region, as the phase transition to the liquid phase has already occurred, the spatial curvature becomes flat under the coupling effect of surface forces. The capillary force is gradually reduced, so that the thermocapillary force of this region gradually dominates (see

Figure 11c). At the same time, in the 68 < x < 118 μm region, the maximum temperature reaches 3287 K, which is close to the evaporation temperature of Ti6Al4V (3315 K); part of the material in this region is removed by evaporation to generate a recoil pressure.

In order to investigate the influence of different process parameters on the laser polishing effect of EB-PBF Ti6Al4V from the perspective of numerical simulation, the surface force distribution of the molten pool under different LPP and LPS is plotted, and

Figure 12a–d shows the surface force distribution and the corresponding molten pool morphology when the LPPD is 3900 kW/cm

2, 5200 kW/cm

2, 7790 kW/cm

2, and 10,400 kW/cm

2, and the laser polishing time is 0.4 ms, respectively. When the LPPD is 3900 kW/cm

2, the laser energy is not enough to make the vertical surface of EB-PBF Ti6Al4V entirely covered by the molten pool, which affects the influence of the surface force on the flow and makes the laser polishing effect very poor. When the LPPD is 5200 kW/cm

2 and 7790 kW/cm

2, the laser energy is enough to make the molten pool cover the entire vertical surface, but, at this time, the thermocapillary force is always difficult to occupy the dominant position in the occupation of the surface force. According to the previous section, we can see that the appropriate thermocapillary force is the key factor to make the molten pool flow to the two sides, and the lack of thermocapillary force makes ability of the molten pool to move in the tangential direction poor, which affects the final polishing effect. When the LPPD is 10,400 kW/cm

2, while sufficient laser energy can keep the thermo-capillary force as dominant, at the same time, a reasonable recoil pressure further suppresses the protruding part of the vertical surface.

Figure 13a–d shows the surface force distribution and the corresponding melt pool morphology when the LPS is 500 mm/s, 600 mm/s, 800 mm/s, and 1000 mm/s, and the laser focus moves to the same position. When the LPS is 500 mm/s and 600 mm/s, the accumulation of energy makes the thermocapillary force dominant for a long period of time due to the slow laser moving speed. The amount of fluid flowing from the center to the edge is too much, which makes the molten pool show a tilted state and affects the final polishing effect. When the LPS is 1000 mm/s, because the laser energy moves too fast, the accumulated laser energy is not enough to make the vertical surface of the peaks reduce but not completely disappear. When the LPS is 800 mm/s, at this time, the laser power and laser movement speed are in a balanced state, and the vertical surface is in the best flat state. For the effect of LPT, it was experimentally found that when the LPT is more than 1 time, the accumulation of laser energy will induce molten pool spattering, which has a negative impact on the surface roughness of the parts.

This study focuses on the molten pool dynamics of laser polishing and discusses the influence of continuous-laser polishing process parameters on polish quality. The laser energy transforms the material along the polishing path from the solid phase to the liquid and gas phases. After the material becomes liquid, a molten pool is formed. Under the action of surface tension caused by the difference in surface curvature, thermocapillary force induced by a temperature gradient, and vapor recoil pressure during the liquid–gas phase transition, the surface curvature gradually decreases. This eliminates the partially melted particles adhering to the side surface of the sample during the EB-PBF process. At the same time, in the later stages of laser polishing, thermocapillary force and recoil pressure dominate the surface forces due to temperature accumulation. The tangential flow induced by the thermocapillary force and the normal flow induced by the recoil pressure cause the end of the polishing path to flow toward the previously flattened region of the surface curvature, forming smaller waves. The roughness analysis results for the polished side surface of EB-PBF Ti6Al4V show that higher laser polishing power density (LPPD) is advantageous in increasing the coverage area of the melt pool, increasing the surface forces in the melt pool, and improving the leveling ability of the peaks and valleys of the molten pool. A lower LPPD, when faced with a very rough side surface, has difficulty eliminating a large number of semi-melted particles, resulting in poorer polishing effects. Moderate laser polishing speed (LPS) settings help balance the polishing process by preventing excessive laser heat buildup, which could lead to excessive surface forces causing molten pool splashing, or insufficient laser energy, which makes it difficult to eliminate semi-melted particles. In addition, a lower laser polishing time (LPT) is beneficial for slowing heat accumulation under high power conditions.