Long-Lasting Hydrophilicity of Al2O3 Surfaces via Femtosecond Laser Microprocessing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Experimental Section

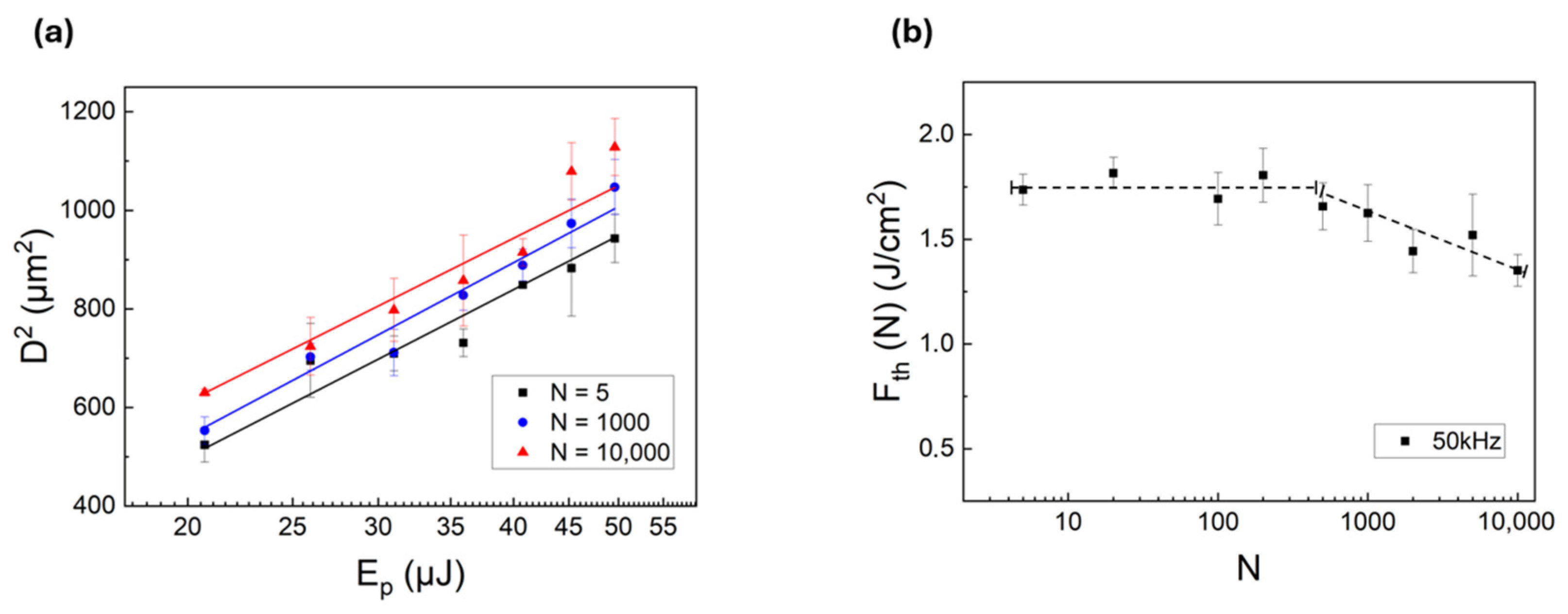

3.1. Ablation Threshold of Alumina with Femtosecond Laser Pulses

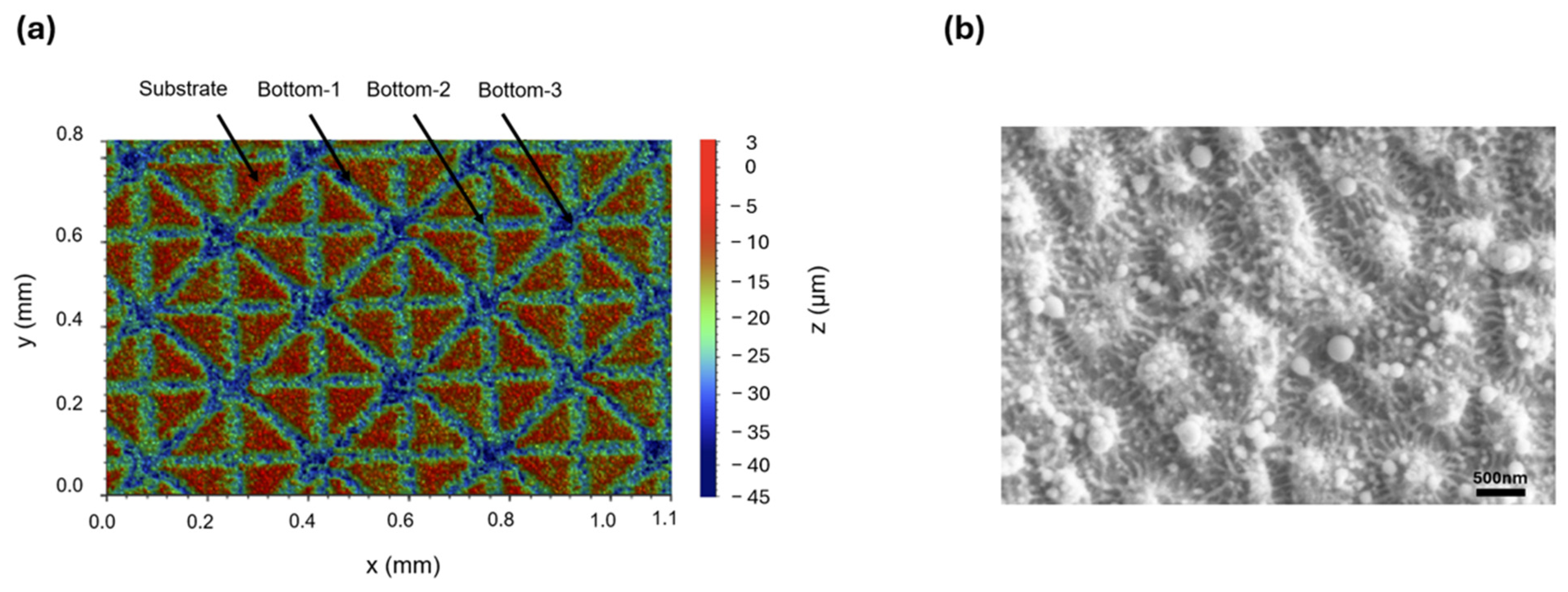

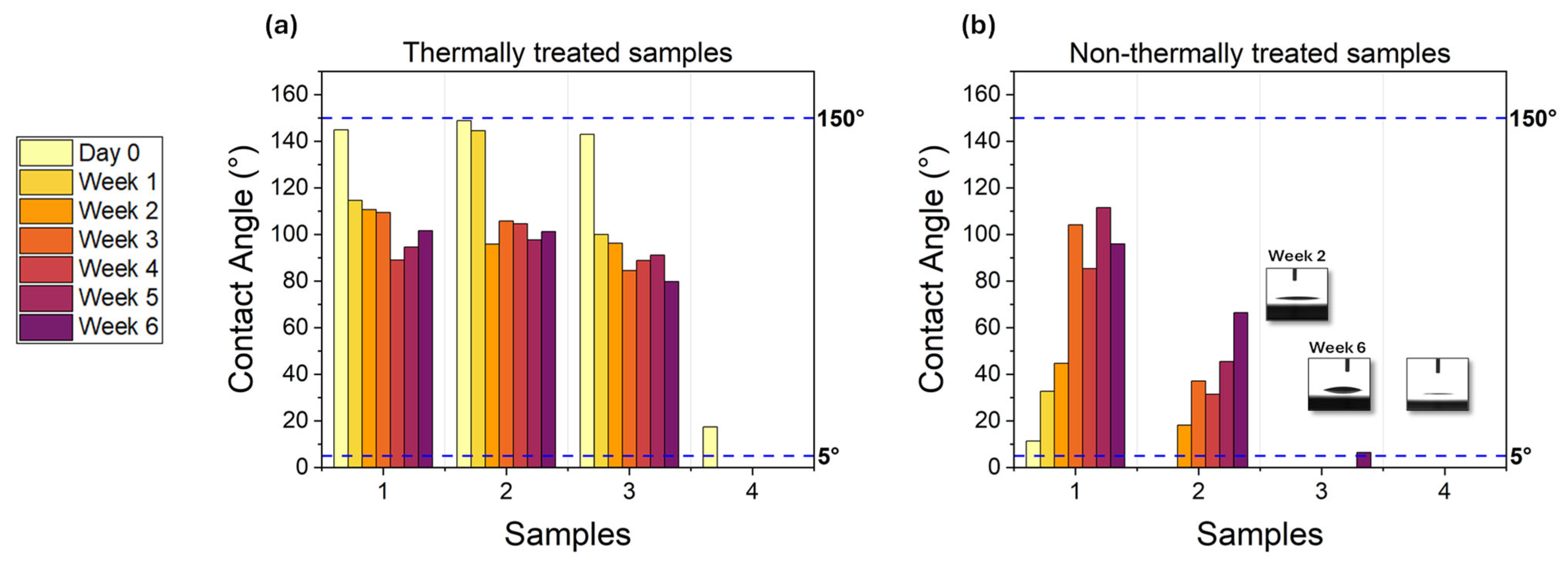

3.2. Role of Femtosecond Laser Microtexturing on Alumina Wettability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Auerkari, P. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Engineering Alumina Ceramics; Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 1996; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.C.; Zheng, H.Y.; Chu, P.L.; Tan, J.L.; Teh, K.M.; Liu, T.; Tay, G.H. Femtosecond laser drilling of alumina ceramic substrates. Appl. Phys. A 2010, 101, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrie, W.; Rushton, A.; Gill, M.; Fox, P.; O’Neill, W. Femtosecond laser micro-structuring of alumina ceramic. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2005, 248, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, S.; Yang, C.; Qi, H.; Jaffery, S.H.I. Effect of surface modification on wettability and tribology by laser texturing in Al2O3. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 4434–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Xiang, Y.; Jia, X. Laser drilling of alumina ceramic substrates: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rung, S.; Häcker, N.; Hellmann, R. Micromachining of alumina using a high-power ultrashort-pulsed laser. Materials 2022, 15, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leese, H.; Bhurtun, V.; Lee, K.P.; Mattia, D. Wetting behaviour of hydrophilic and hydrophobic nanostructured porous anodic alumina. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2013, 420, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdheesh, R. Fabrication of a superhydrophobic Al2O3 surface using picosecond laser pulses. Langmuir 2014, 30, 12067–12073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.R.S.; Santos, L.N.R.M.; Farias, R.M.C.; Sousa, B.V.; Neves, G.A.; Menezes, R.R. Alumina applied in bone regeneration: Porous α-alumina and transition alumina. Cerâmica 2022, 68, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafikova, G.; Piatnitskaia, S.; Shapovalova, E.; Chugunov, S.; Kireev, V.; Ialiukhova, D.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Interaction of ceramic implant materials with immune system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarino, G.; Vicenti, G.; Piazzolla, A.; Piconi, C.; Moretti, B. Ceramic-Ceramic Hip Arthroplasty. Ital. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2013, 39, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Moameri, H.H.; Nahi, Z.M.; Rzaij, D.R.; Al-Sharify, N.T. A review on the biomedical applications of alumina. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 24, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, X.; Akbulut, O.; Hu, J.; Suib, S.L.; Kong, J.; Stellacci, F. Superwetting nanowire membranes for selective absorption. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Saito, N.; Takai, O. Correlation of cell adhesive behaviors on superhydrophobic, superhydrophilic, and micropatterned superhydrophobic/superhydrophilic surfaces to their surface chemistry. Langmuir 2010, 26, 8147–8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passerone, A.; Valenza, F.; Muolo, M.L. A review of transition metals diborides: From wettability studies to joining. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 8275–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Kuo, C.P. Evaluation of surface roughness in laser-assisted machining of aluminum oxide ceramics with Taguchi method. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2007, 47, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Guan, K.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, N.; Guan, Y. Engineered functional surfaces by laser microprocessing for biomedical applications. Engineering 2018, 4, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, D.; Li, L.; Stott, F.H. The effects of laser-induced modification of surface roughness of Al2O3-based ceramics on fluid contact angle. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 390, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.; Bartolome, J.F.; Gnecco, E.; Muller, F.A.; Graf, S. Selective generation of laser-induced periodic surface structures on Al2O3-ZrO2-Nb composites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; Guan, Y. Fabrication of superhydrophilic surface on alumina ceramic by ultrafast laser microprocessing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 557, 149842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Y. Super Hydrophilic Surface Fabricated on Alumina Ceramic by Ultrafast Laser Microprocessing. J. Laser Micro/Nanoeng. 2021, 16, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- CoorsTek. Al2O3 Thick-Film Ceramic Substrates Design Guide. Available online: https://www.coorstek.com (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Liu, J.M. Simple technique for measurements of pulsed Gaussian-beam spot sizes. Opt. Lett. 1982, 7, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriukaitis, D. Examining Ablation Efficiency in Alumina Ceramics Utilizing Femtosecond Laser with MHz/GHz Burst Regime. Ph.D. Thesis, Vilniaus Universitetas, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Di Niso, F.; Gaudiuso, C.; Sibillano, T.; Mezzapesa, F.P.; Ancona, A.; Lugarà, P.M. Role of heat accumulation on the incubation effect in multi-shot laser ablation of stainless steel at high repetition rates. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 12200–12210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfregola, F.A.; De Palo, R.; Gaudiuso, C.; Mezzapesa, F.P.; Patimisco, P.; Ancona, A.; Volpe, A. Influence of working parameters on multi-shot femtosecond laser surface ablation of lithium niobate. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palo, R.; Volpe, A.; Gaudiuso, C.; Patimisco, P.; Spagnolo, V.; Ancona, A. Threshold fluence and incubation during multi-pulse ultrafast laser ablation of quartz. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 44908–44917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, A.; Covella, S.; Gaudiuso, C.; Ancona, A. Improving the laser texture strategy to get superhydrophobic aluminum alloy surfaces. Coatings 2021, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiuso, C.; Fanelli, F.; Volpe, A.; Ancona, A.; Buogo, S.; Mezzapesa, F. Unlocking ultrasound manipulation by laser-engineered hierarchical nanostructures. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2025, 58, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Qian, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Q. Heat accumulation effects in femtosecond laser-induced subwavelength periodic surface structures on silicon. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2023, 21, 051402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.V.; Chun, D.M. Fast wettability transition from hydrophilic to superhydrophobic laser-textured stainless steel surfaces under low-temperature annealing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 409, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzapesa, F.P.; Gaudiuso, C.; Volpe, A.; Ancona, A.; Mauro, S.; Buogo, S. Underwater acoustic camouflage by wettability transition on laser textured superhydrophobic metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 11, 2400124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, X. Femtosecond laser patterned alumina ceramics surface towards enhanced superhydrophobic performance. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 15426–15434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Yang, Q.; Hou, X.; Chen, F. Nature-inspired superwettability achieved by femtosecond lasers. Ultrafast Sci. 2022, 2022, 9895418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Repetition rates [kHz] | 50–25–10–5–1 |

| Number of pulses (N) | 5–20–100–200–500–1000–2000–5000–10,000 |

| Pulse energy (Ep) [µJ] | 49.6–45.3–40.8–35.9–31–25.9–20.7 |

| Sample | Depth [µm] | Scan Speed [mm/s] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 750 |

| 2 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 250 |

| 3 | 13.2 ± 0.1 | 80 |

| 4 | 17.1 ± 0.1 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Signorile, A.; Papa, L.; Pontrandolfi, M.; Gaudiuso, C.; Volpe, A.; Ancona, A.; Mezzapesa, F.P. Long-Lasting Hydrophilicity of Al2O3 Surfaces via Femtosecond Laser Microprocessing. Micromachines 2026, 17, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010029

Signorile A, Papa L, Pontrandolfi M, Gaudiuso C, Volpe A, Ancona A, Mezzapesa FP. Long-Lasting Hydrophilicity of Al2O3 Surfaces via Femtosecond Laser Microprocessing. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSignorile, Alessandra, Liliana Papa, Marida Pontrandolfi, Caterina Gaudiuso, Annalisa Volpe, Antonio Ancona, and Francesco Paolo Mezzapesa. 2026. "Long-Lasting Hydrophilicity of Al2O3 Surfaces via Femtosecond Laser Microprocessing" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010029

APA StyleSignorile, A., Papa, L., Pontrandolfi, M., Gaudiuso, C., Volpe, A., Ancona, A., & Mezzapesa, F. P. (2026). Long-Lasting Hydrophilicity of Al2O3 Surfaces via Femtosecond Laser Microprocessing. Micromachines, 17(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010029