Cascade Dielectrophoretic Separation for Selective Enrichment of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Producing Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Physics and Simulation of the Dielectrophoretic Separation

2.2. Strain and Cultivation Conditions

2.3. Electrode Fabrication

2.4. Electrokinetic Separation Cascade

2.5. Flow Cytometry

3. Results and Discussion

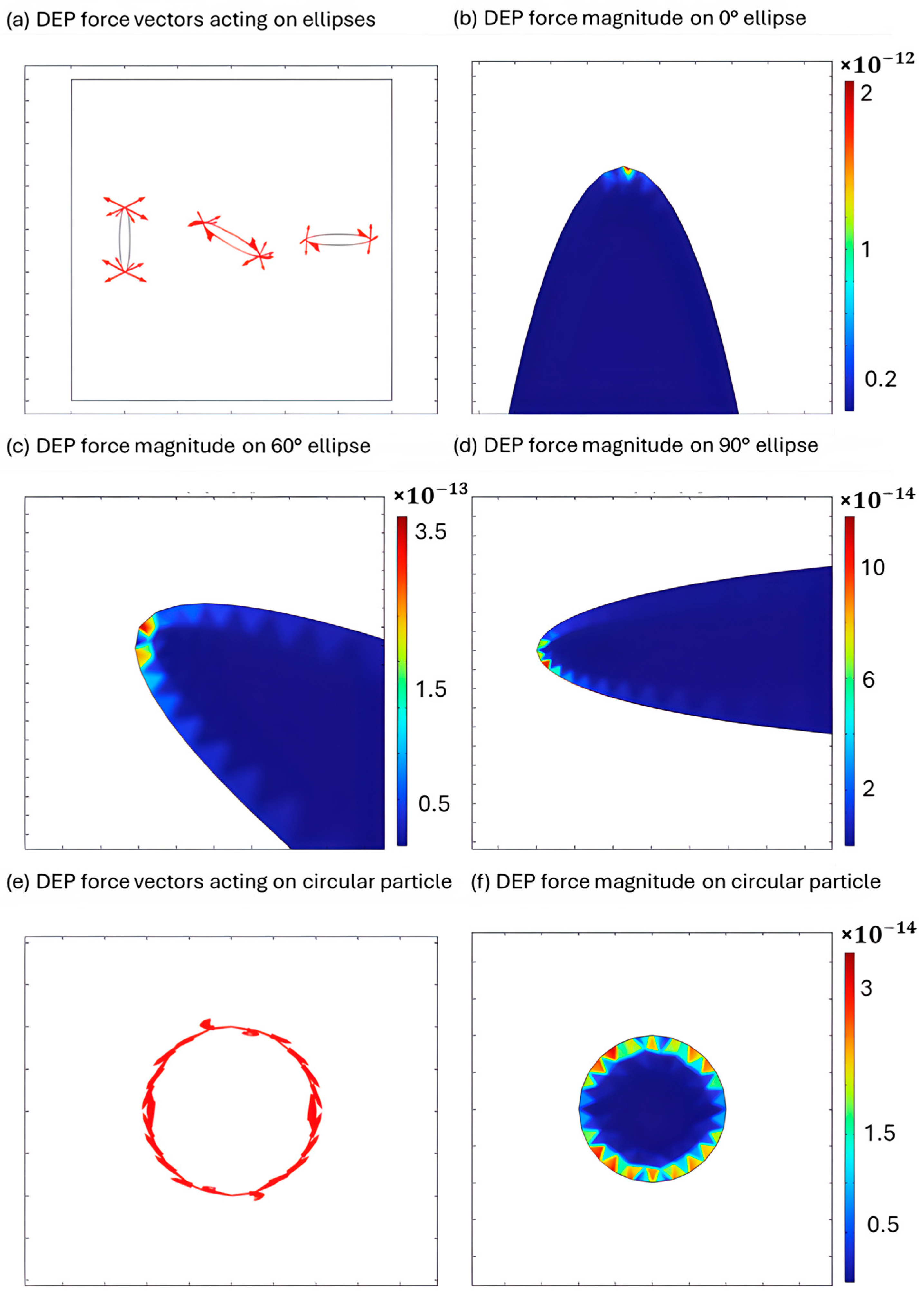

3.1. Simulation Results

3.2. Evaluation of Feasibility of DEP-Based Cell Separation

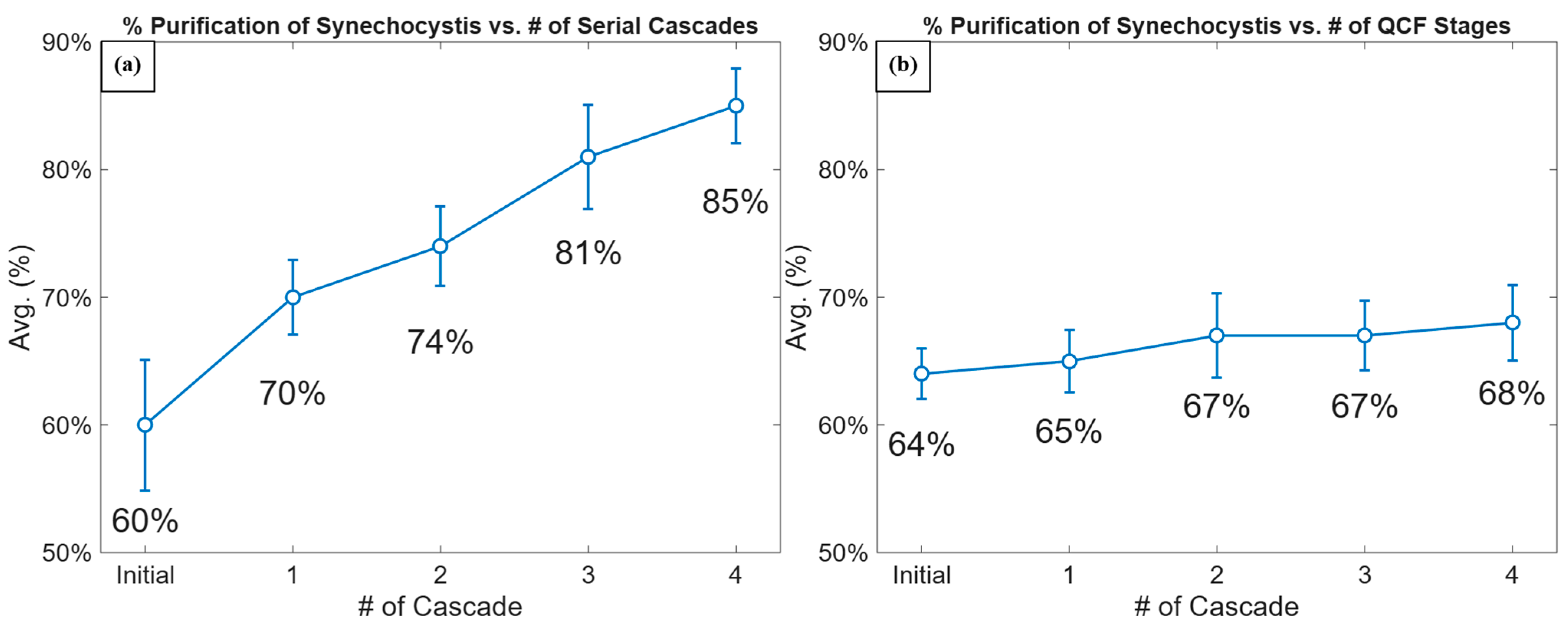

3.3. The Cascade Dielectrophoretic Separation

3.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gleizer, S.; Bar-On, Y.M.; Ben-Nissan, R.; Milo, R. Engineering microbes to produce fuel, commodities, and food from CO2. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.E.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. The microbial food revolution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Dong, Q.; Che, S.; Li, R.; Tang, K.H.D. Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics: A review of recent advances, feasibility and cleaner production. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Cho, B.K.; Lee, D.-H. Synthetic biology-driven microbial therapeutics for disease treatment. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.P.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y. Biomanufacturing: History and perspective. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos Rodriguez-Conde, F.; Zhu, S.; Dikicioglu, D. Harnessing microbial division of labor for biomanufacturing: A review of laboratory and formal modeling approaches. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2025, 45, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieenia, R.; Klemm, C.; Hapeta, P.; Fu, J.; García, M.G.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Designing synthetic microbial communities with the capacity to upcycle fermentation byproducts to increase production yields. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururani, P.; Bhatnagar, P.; Kumar, V.; Vlaskin, M.S.; Grigorenko, A.V. Algal consortiums: A novel and integrated approach for wastewater treatment. Water 2022, 14, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Min, K.J.; Park, K.Y. Changes in anaerobic digestion performance and microbial community by increasing SRT through sludge recycling in food waste leachate treatment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbing, M.E.; Fuqua, C.; Parsek, M.R.; Peterson, S.B. Bacterial competition: Surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, K.; Lavoie, A.; Rao, B.M.; Daniele, M.; Menegatti, S. Past, present, and future of affinity-based cell separation technologies. Acta Biomater. 2020, 112, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roush, D.J.; Lu, Y. Advances in primary recovery: Centrifugation and membrane technology. Biotechnol. Prog. 2008, 24, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Patidar, S.K. Microalgae harvesting techniques: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaamoo, M.; Cardenas-Benitez, B.; Lee, A.P. A high-throughput microfluidic cell sorter using a three-dimensional coupled hydrodynamic-dielectrophoretic pre-focusing module. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapizco-Encinas, B.H. Nonlinear electrokinetic methods of particles and cells. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 17, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Rajestari, Z.; Morse, T.C.; Li, H.; Kulinsky, L. Electrokinetic manipulation of biological cells towards biotechnology applications. Micromachines 2024, 15, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhao, K.; Lou, J.; Zhang, K. Recent advances in dielectrophoretic manipulation and separation of microparticles and biological cells. Biosensors 2024, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Patel, S.H.; Johnson, M.; Kale, A.; Raval, Y.; Tzeng, T.R.; Xuan, X. Enhanced throughput for electrokinetic manipulation of particles and cells in a stacked microfluidic device. Micromachines 2016, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, N.J.; Rabinovitch-Deere, C.A.; Carroll, A.L.; Nozzi, N.E.; Case, A.E.; Atsumi, S. Cyanobacterial metabolic engineering for biofuel and chemical production. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 35, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Esquer, C.R.; Smarda, J.; Rippka, R.; Axen, S.D.; Guglielmi, G.; Gugger, M.; Kerfeld, C.A. Cyanobacterial ultrastructure in light of genomic sequence data. Photosynth. Res. 2016, 129, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmann, E.; Gugger, M.; Sivonen, K.; Fewer, D.P. Natural product biosynthetic diversity and comparative genomics of the cyanobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, S.; Tran, H.; Steinbüchel, A. Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 possesses a two-component polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthase similar to that of anoxygenic purple sulfur bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 1998, 170, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.B. Basic theory of dielectrophoresis and electrorotation methods for determining the forces and torques exerted by nonuniform electric fields on biological particles suspended in aqueous media. In Micro- & Nanoelectrokinetics; Research Studies Press: Baldock, UK, 2003; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H.; Green, N.G. Electrokinetics and Electrohydrodynamics in Microsystems; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bau, H.H. The dielectrophoresis of cylindrical and spherical particles submerged in shells and in semi-infinite media. Phys. Fluids 2004, 16, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.; Al Ahmad, M. Cells electrical characterization: Dielectric properties, mixture, and modeling theories. J. Eng. 2020, 2020, 9475490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eeckhoudt, R.; Rao, N.R.H.; Muylaert, K.; Tavernier, F.; Kraft, M.; Taurino, I. Harnessing intrinsic biophysical cellular properties for identification of algae and cyanobacteria via impedance spectroscopy. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 4081–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanichapichart, P.; Bunthawin, S.; Kaewpaiboon, A.; Kanchanapoom, K. Determination of cell dielectric properties using dielectrophoretic technique. ScienceAsia 2002, 28, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1979, 111, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondot, N.; Yan, S.; Mager, D.; Kulinsky, L. A low-cost printed circuit board-based centrifugal microfluidic platform for dielectrophoresis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Piñón, M.; Pramanick, B.; Ortega-Gama, F.G.; Pérez-González, V.H.; Kulinsky, L.; Madou, M.J.; Hwang, H.; Martinez-Chapa, S.O. Hydrodynamic channeling as a controlled flow reversal mechanism for bidirectional AC electroosmotic pumping using glassy carbon microelectrode arrays. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2019, 29, 075007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage # | Serial Cascades (%) | QCF Stages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage #1 | 39.2 ± 35.2 | 8.3 ± 9.7 |

| Stage #2 | 12.2 ± 7.5 | 29.3 ± 20.4 |

| Stage #3 | 23.8 ± 14.8 | 11.0 ± 11.8 |

| Stage #4 | 24.6 ± 19.1 | 28.4 ± 16.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, S.; Pacheco, S.L.; Laskie, A.K.; Gonzalez Esquer, C.R.; Kulinsky, L. Cascade Dielectrophoretic Separation for Selective Enrichment of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Producing Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121402

Yan S, Pacheco SL, Laskie AK, Gonzalez Esquer CR, Kulinsky L. Cascade Dielectrophoretic Separation for Selective Enrichment of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Producing Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121402

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Songyuan, Sara Louise Pacheco, Asa K. Laskie, Cesar Raul Gonzalez Esquer, and Lawrence Kulinsky. 2025. "Cascade Dielectrophoretic Separation for Selective Enrichment of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Producing Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121402

APA StyleYan, S., Pacheco, S. L., Laskie, A. K., Gonzalez Esquer, C. R., & Kulinsky, L. (2025). Cascade Dielectrophoretic Separation for Selective Enrichment of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Producing Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Micromachines, 16(12), 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121402