Research Progress on Personalized Bone Implants Based on Additive Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

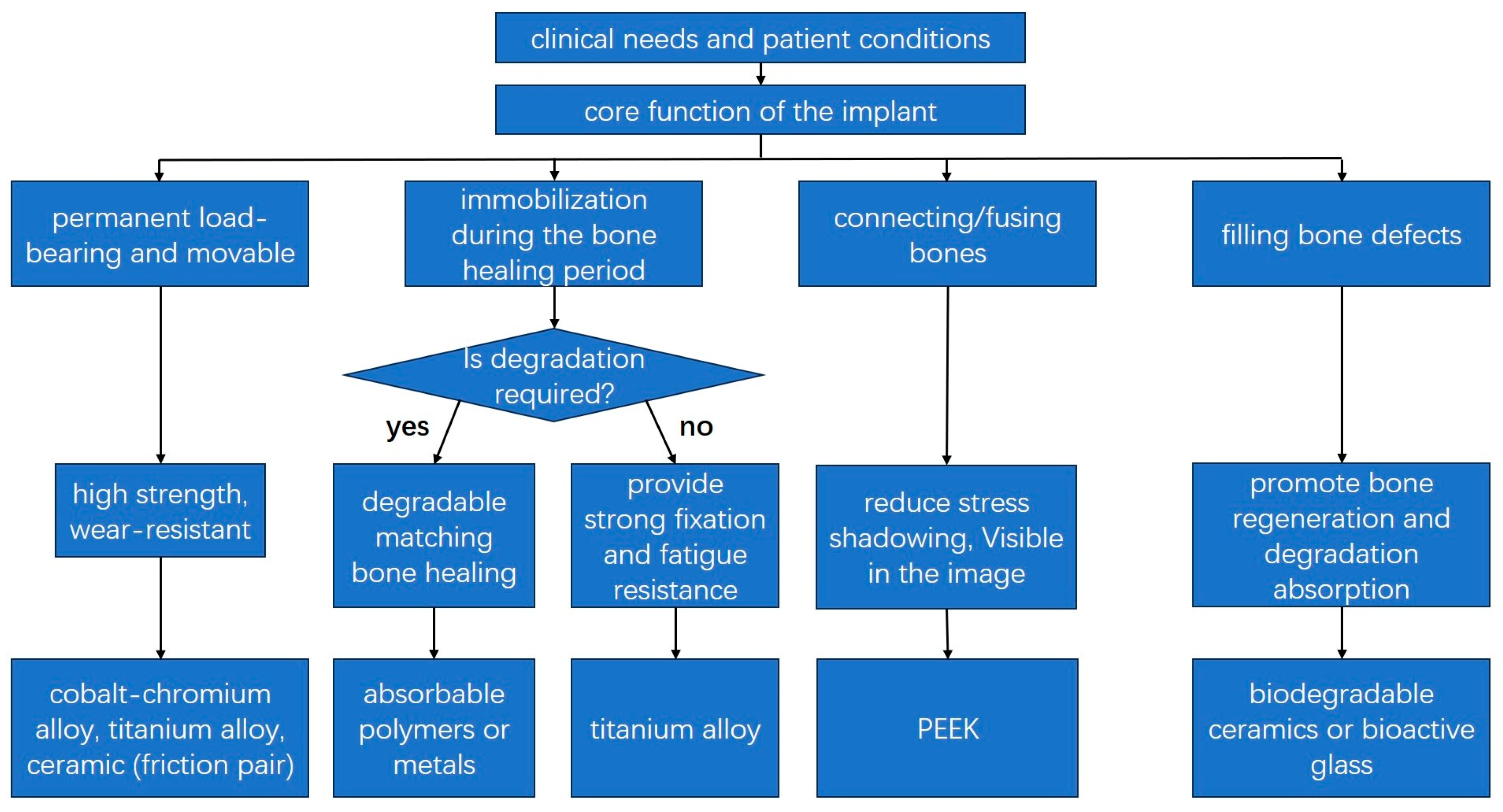

2. Design Method for Personalized Bone Implants

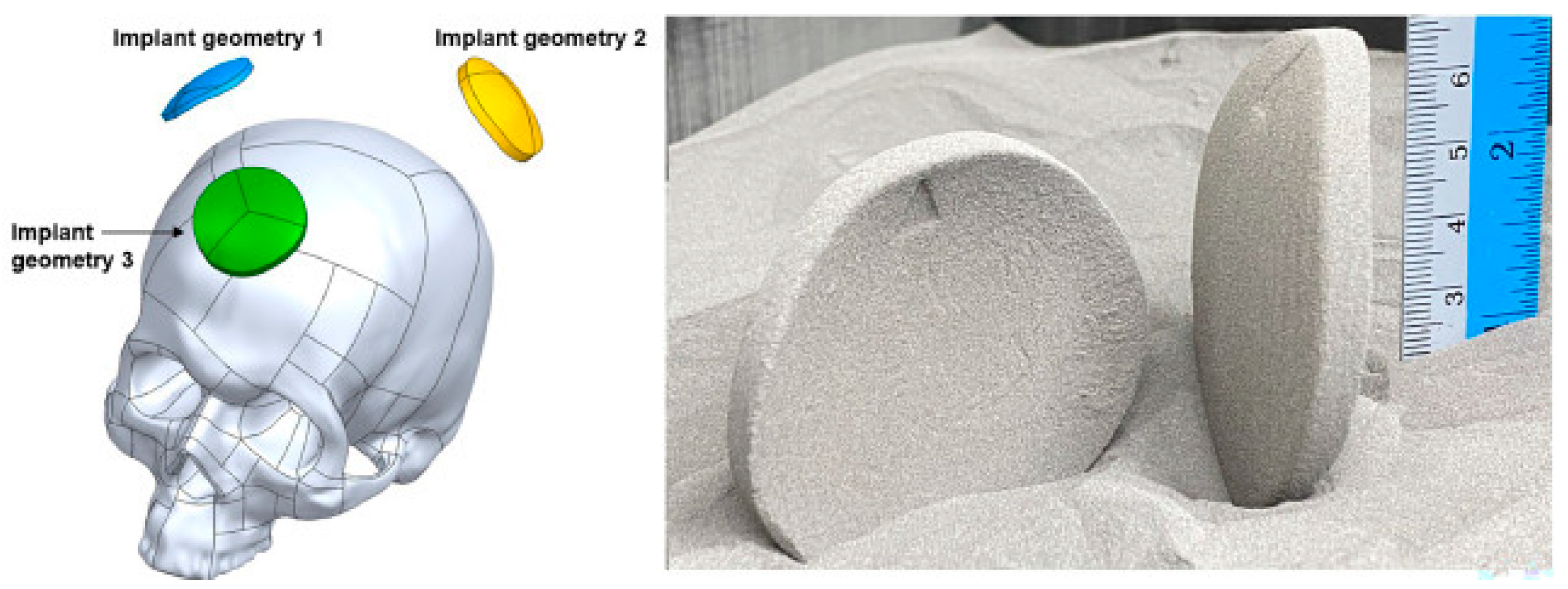

2.1. Medical Imaging and 3D Modeling

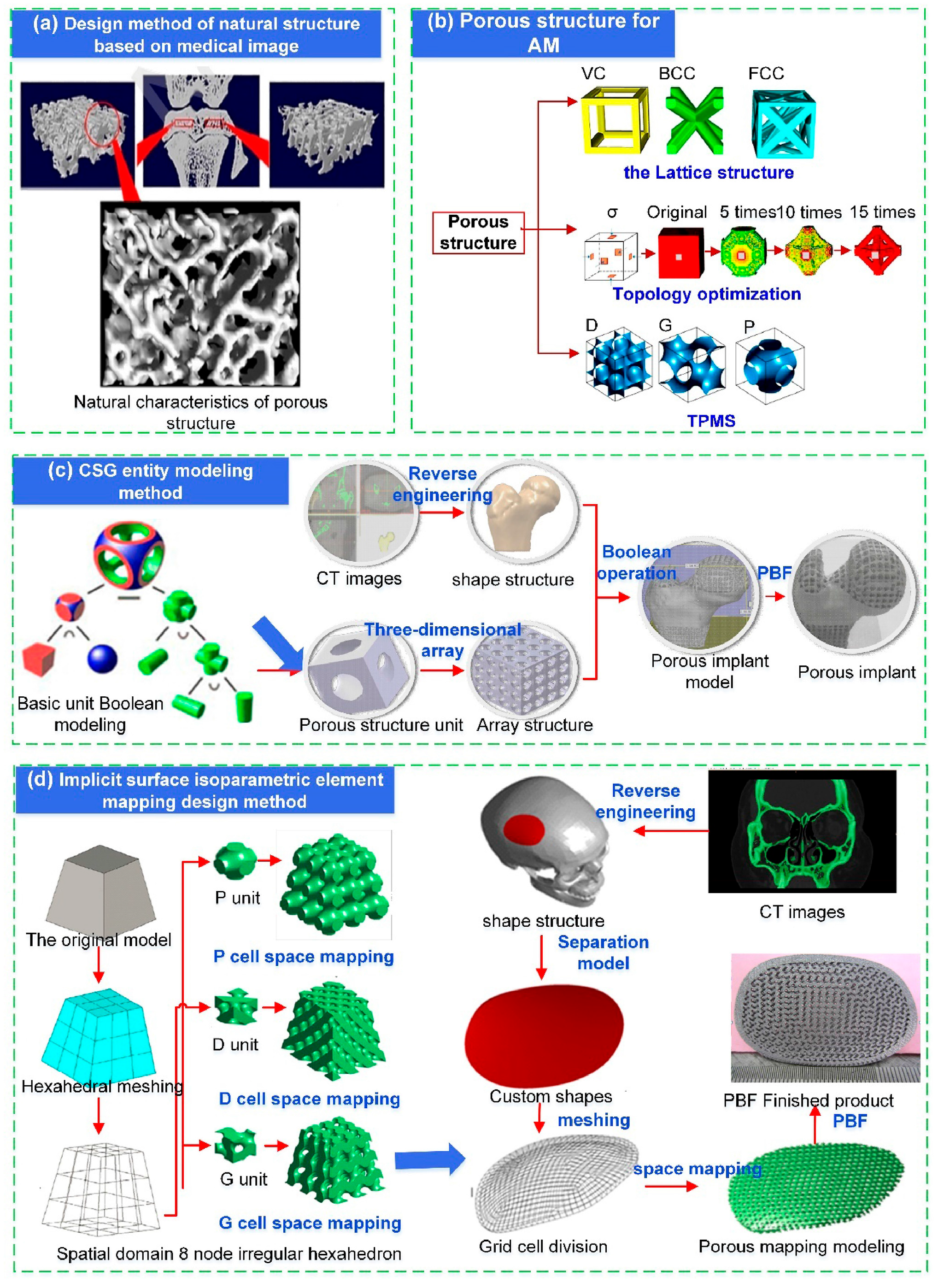

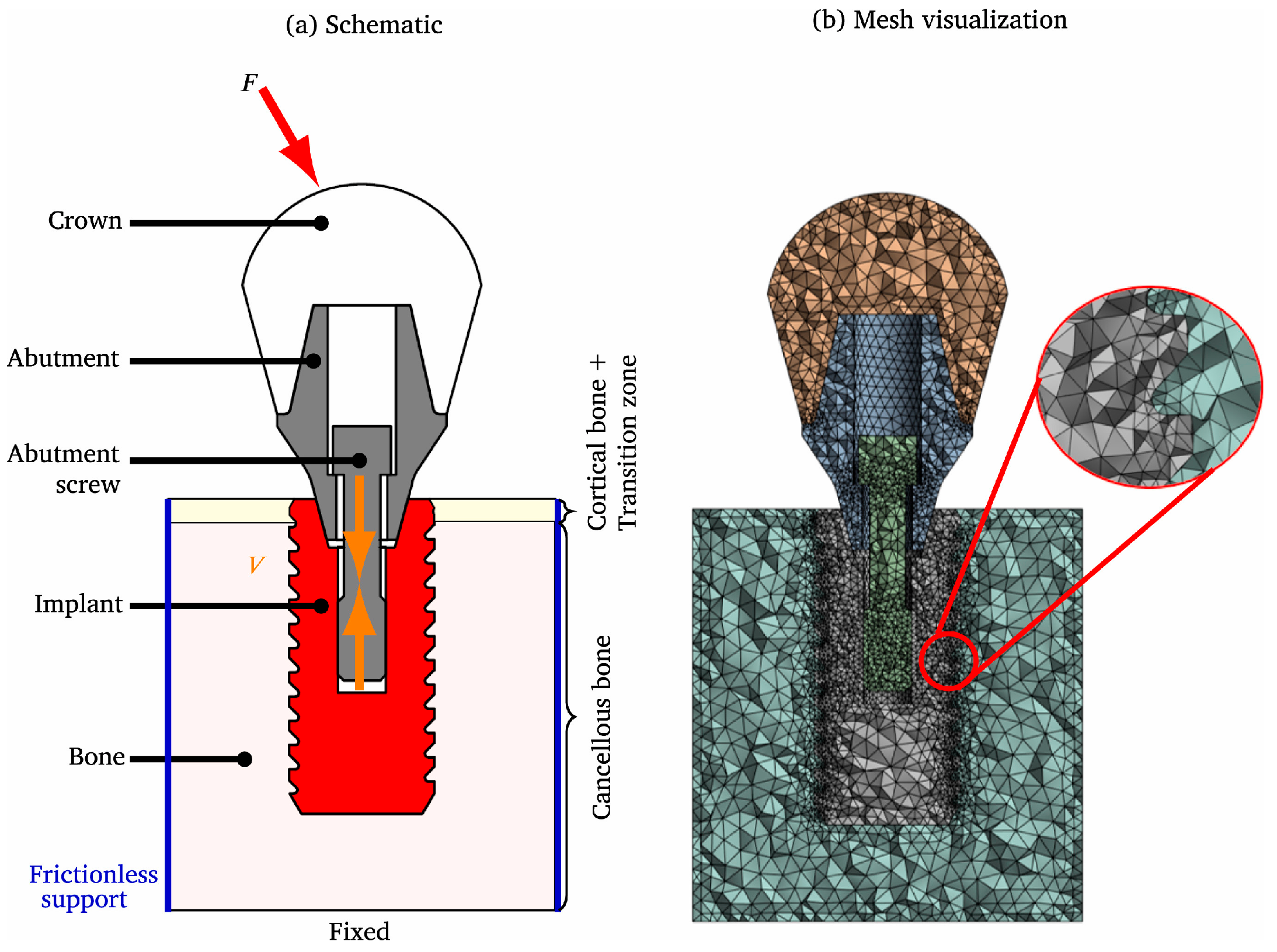

2.2. Design Method for Porous Structures of Implants

2.2.1. Constructive Solid Geometry Method

2.2.2. Topology-Optimization-Based Design of Porous Bone Implants

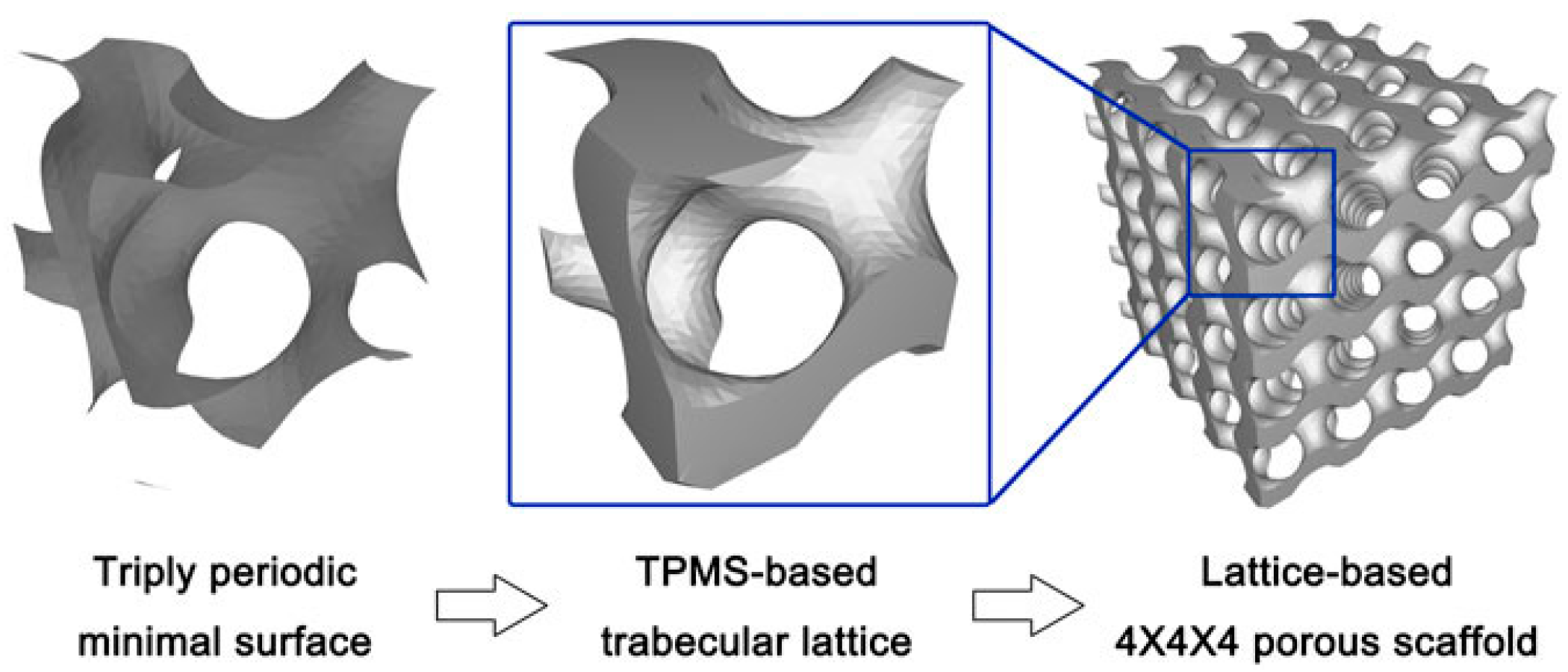

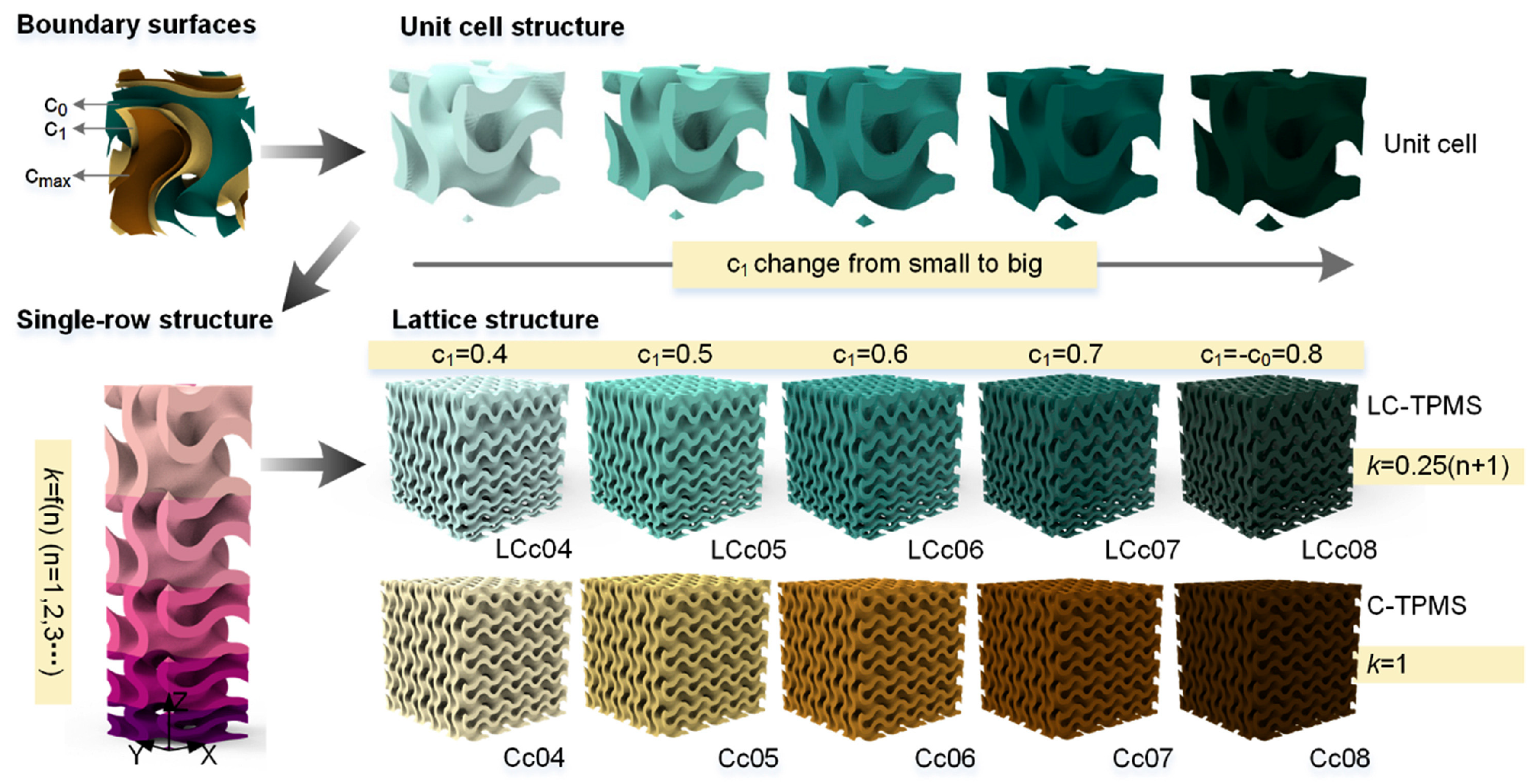

2.2.3. Design Method for Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces

2.2.4. Comparative Analysis of Design Methods

3. Material Systems for Personalized Bone Implants

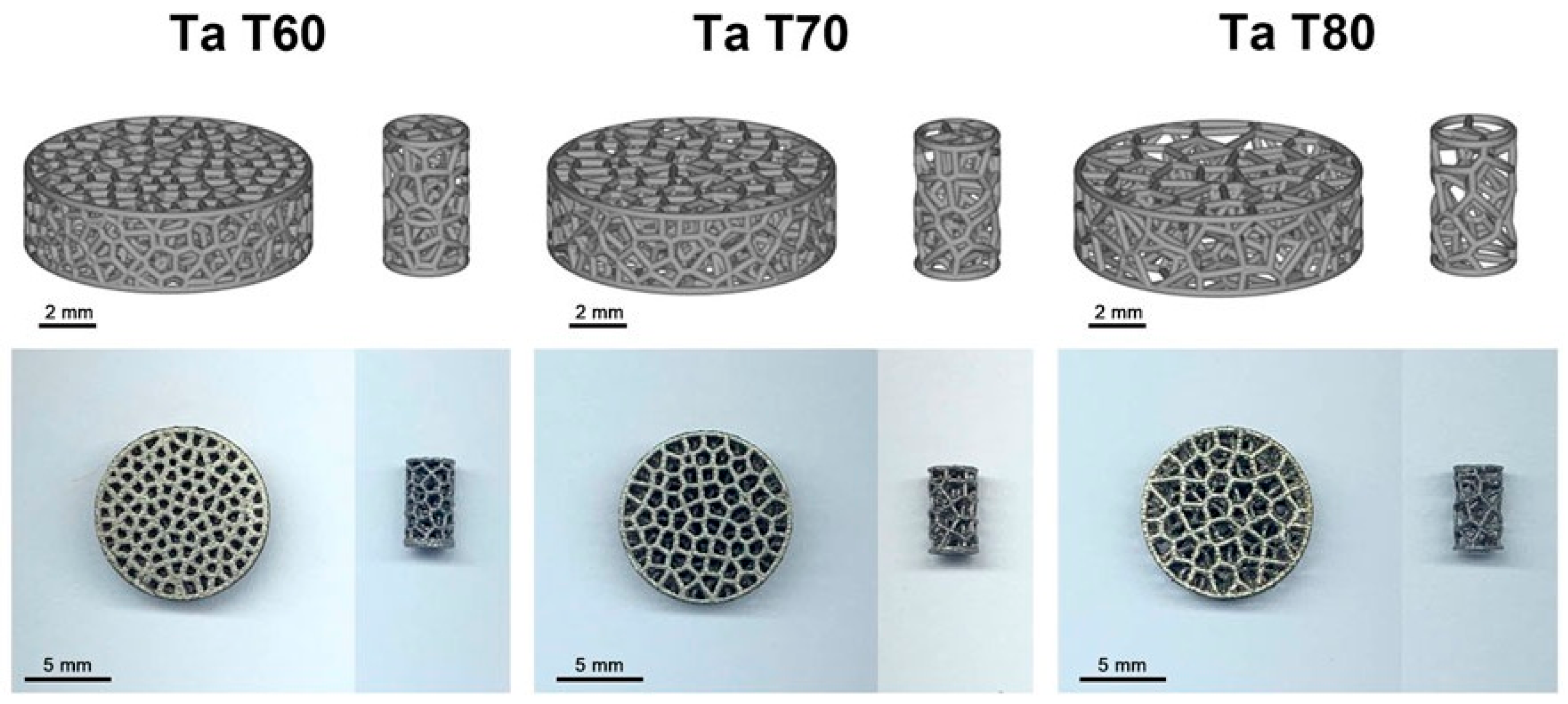

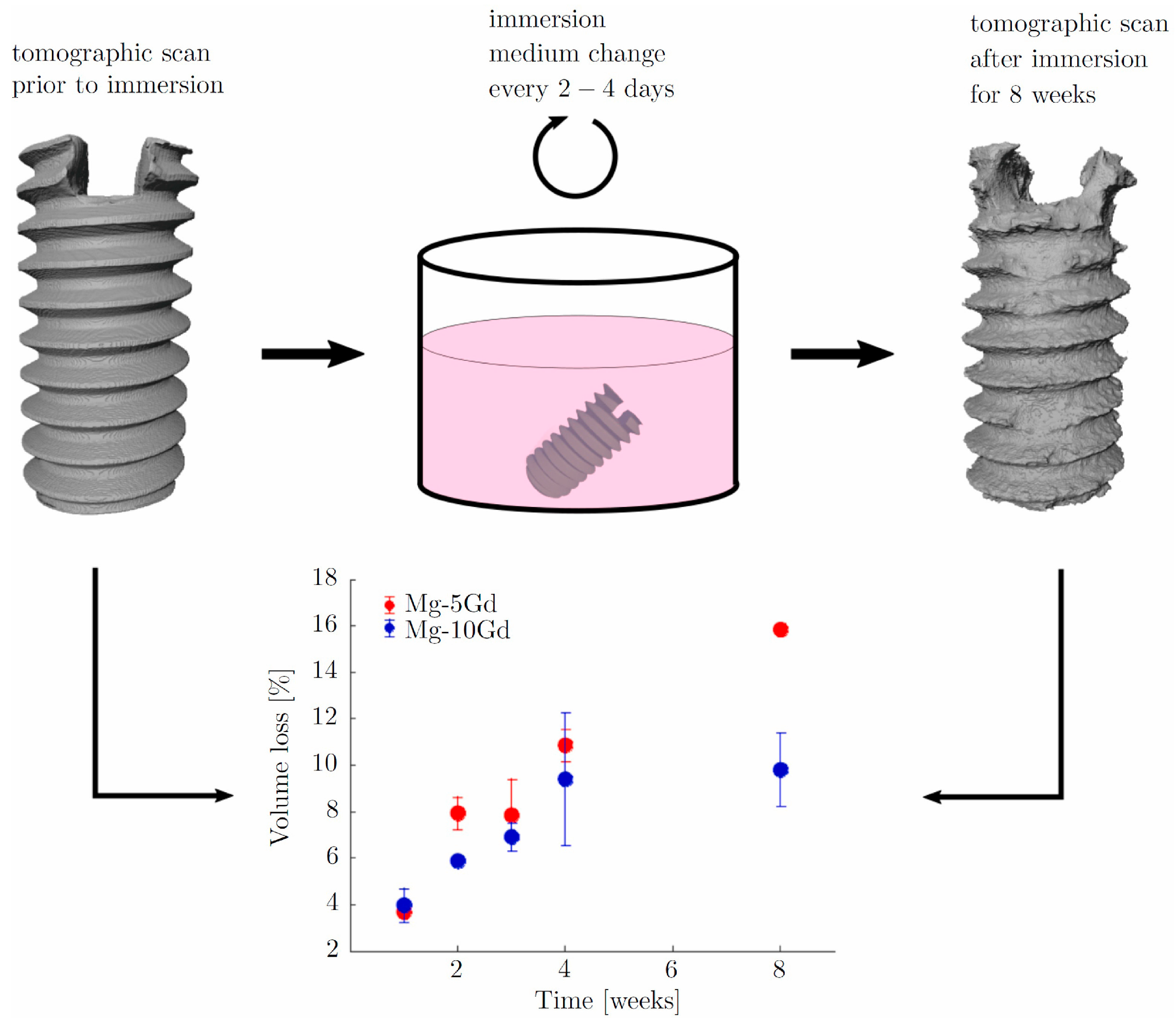

3.1. Metal Materials

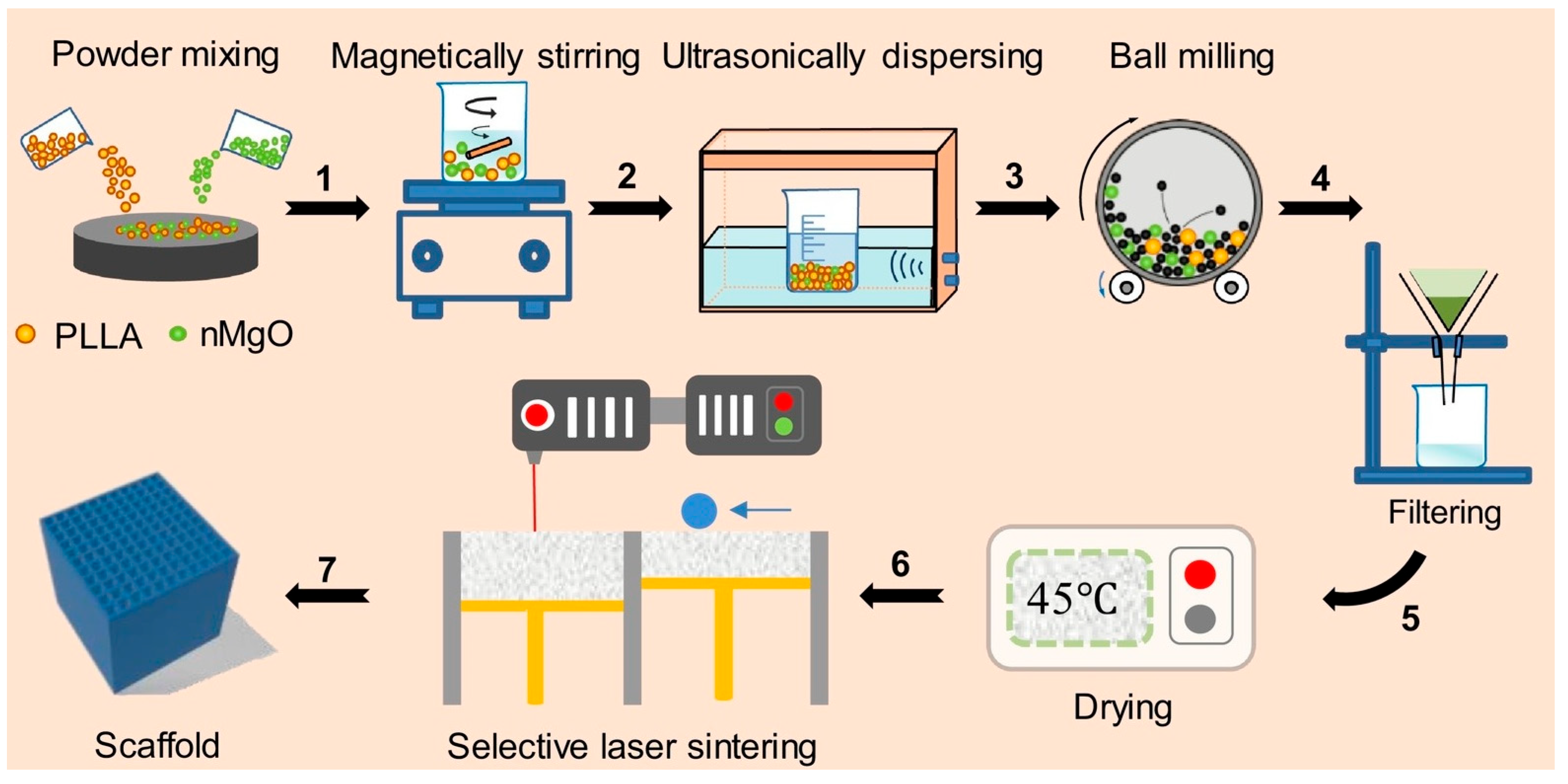

3.2. Polymer Materials

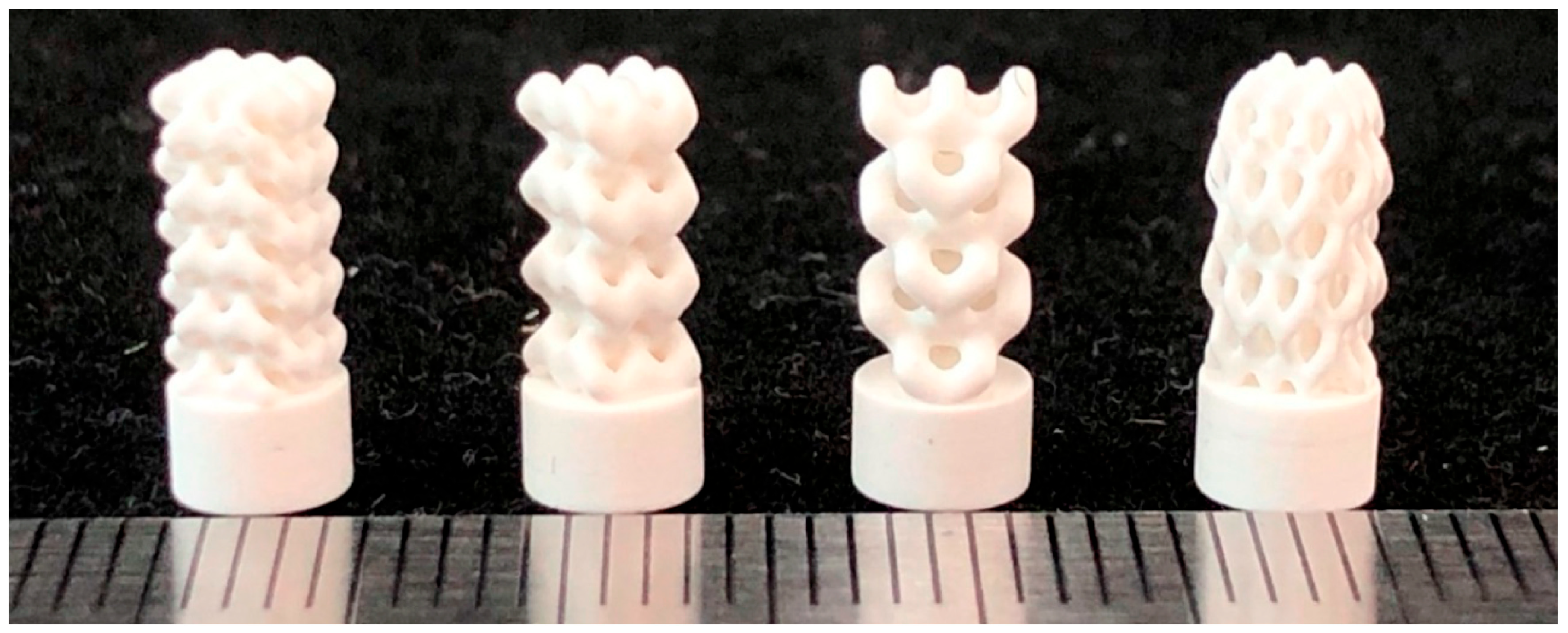

3.3. Ceramic Materials

3.4. Considerations for Material Selection

4. Manufacture Method for Bone Implants Based on Additive Manufacturing

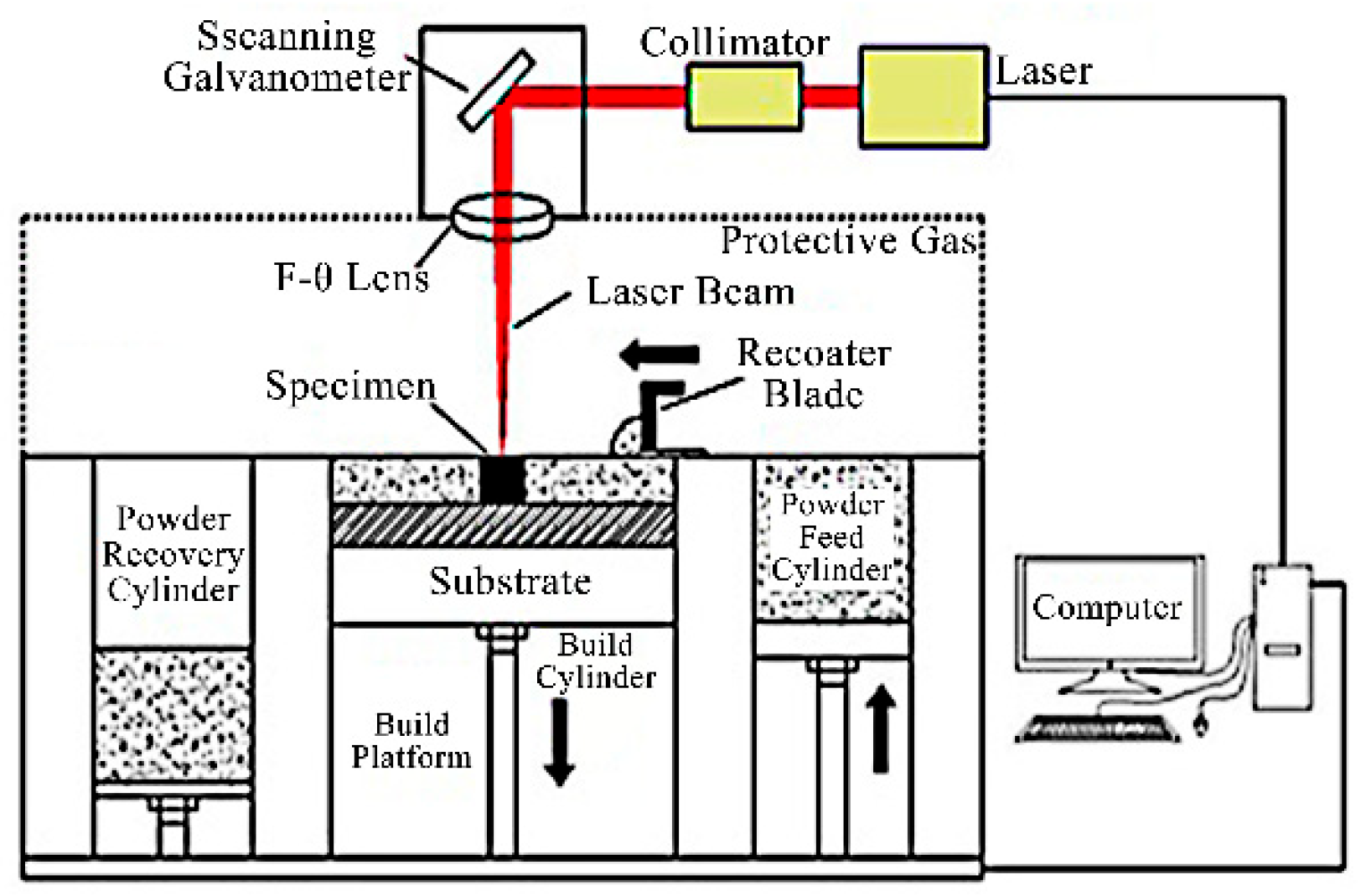

4.1. Powder Bed Fusion

4.1.1. Selective Laser Melting

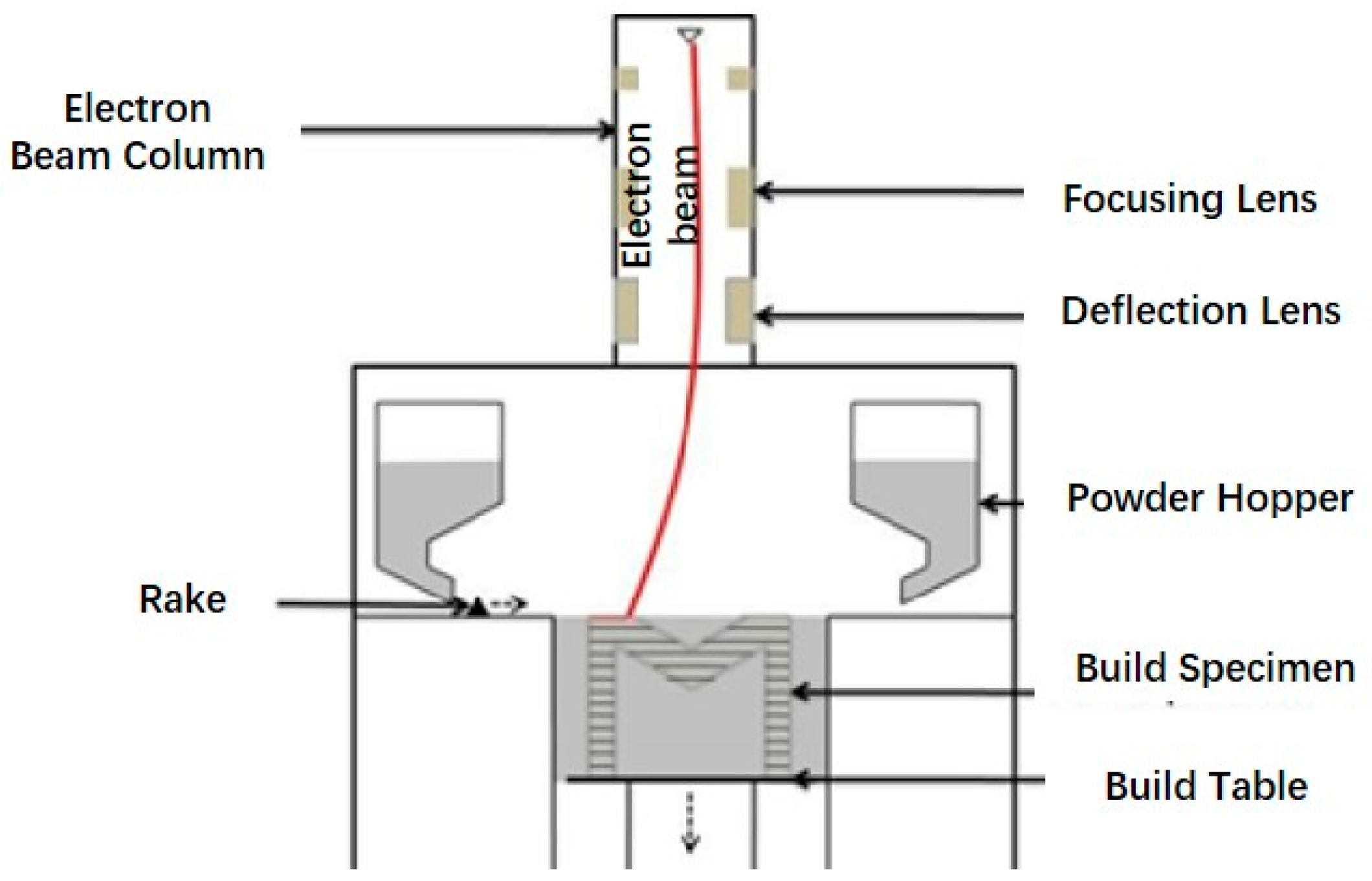

4.1.2. Electron Beam Melting

4.2. Fused Deposition Modeling

4.3. Binder Jetting

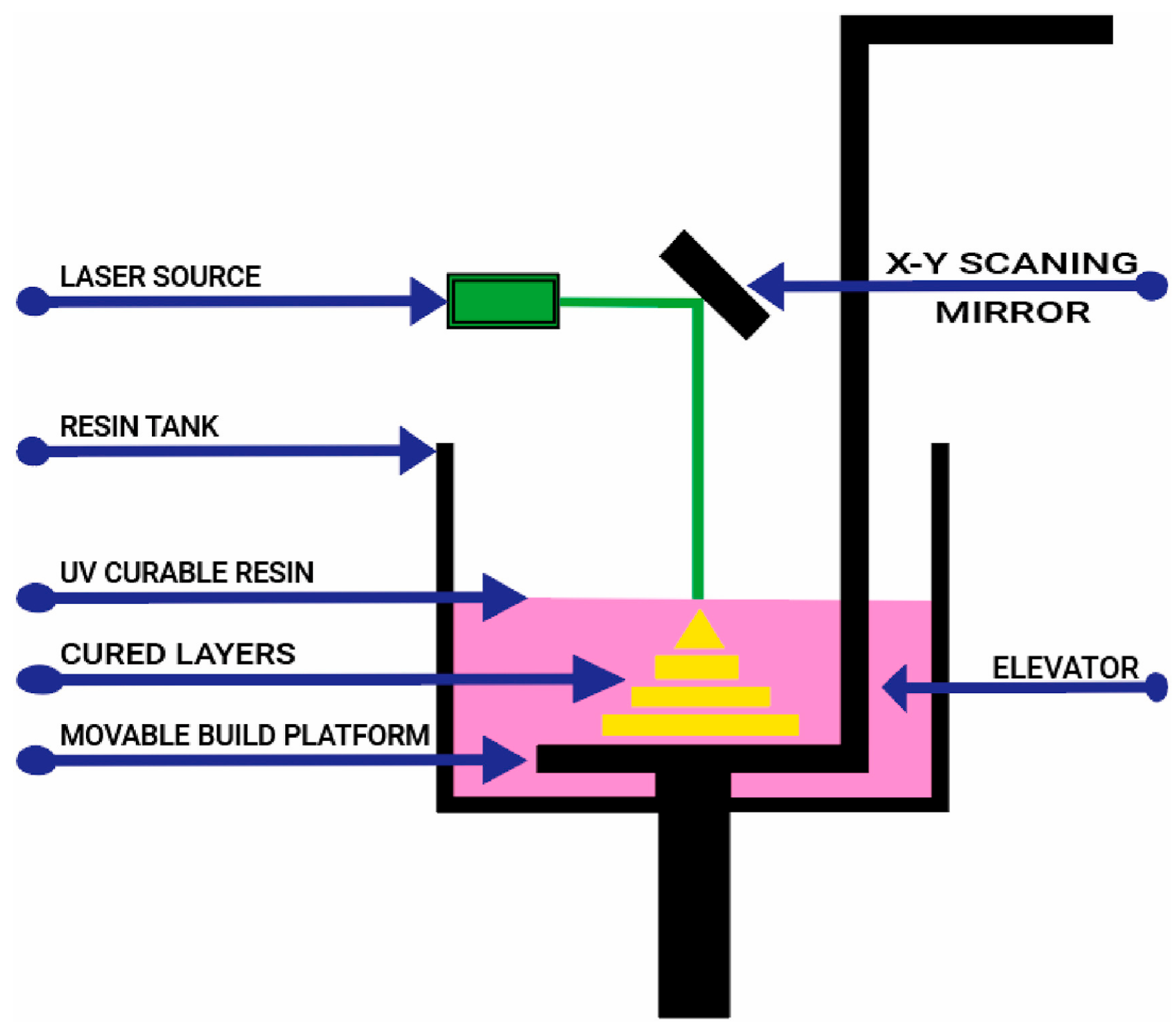

4.4. Stereolithography

4.5. Comparison of Different Additive Manufacturing Technologies

5. Performance Evaluation of Personalized Bone Implants

5.1. Mechanical Property

5.2. Surface Antimicrobial Properties

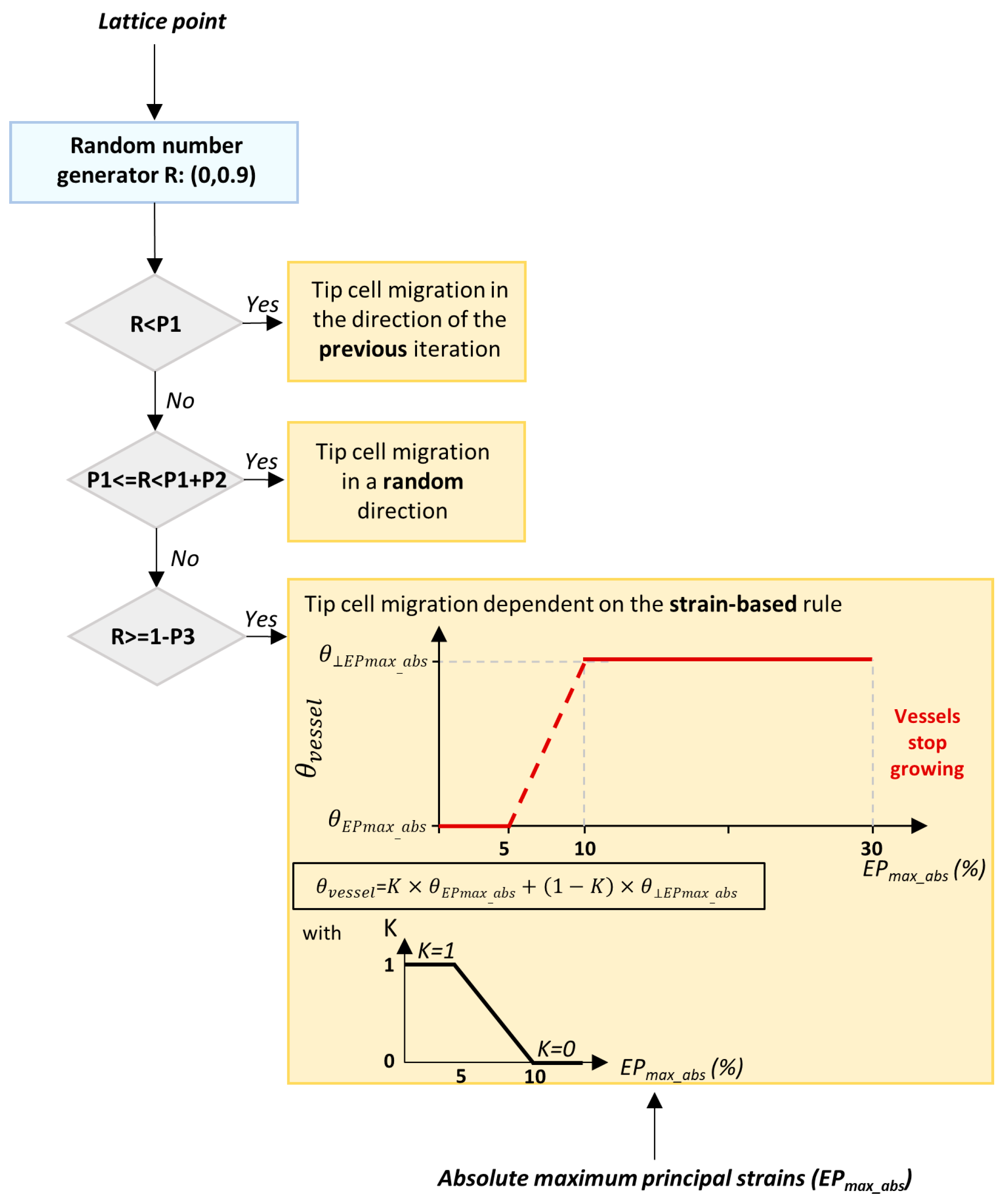

5.3. Osteointegration Effect

6. Application of AI in the Field of Bone Implants

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

- (1)

- Machine learning models can be trained on long-term clinical follow-up data, which can be used to predict patient implant lifespan and identify risk factors. Furthermore, machine learning models can simulate the systematic distribution and biological effects of degradation products, transforming safety assessments from post-analysis to proactive design.

- (2)

- A digital twin virtual platform can overcome regulatory bottlenecks for personalized implants. Implants equipped with biosensors can feed patient physiological data back to their digital twin. This feedback loop can achieve real-time detection of postoperative status, prevent the occurrence of complications, and customize personalized rehabilitation plans.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| Mimics | Materialise’s interactive medical image control system |

| L-PBF | Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| CSG | Constructive Solid Geometry |

| TPMS | Triple Periodic Minimal Surface |

| LSRCMS | layered rod-connected hexagonal porous structure |

| NPR | Negative Poisson’s Ratio |

| OC | optimality criteria |

| HA/HAp | hydroxyapatite |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| β-TCP | β-tricalcium phosphate |

| BCP | biphasic calcium phosphate |

| Mg | magnesium |

| Fe | iron |

| Zn | zinc |

| PEEK | polyether ether ketone |

| UHMWPE | ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene |

| PDA | poly-dopamine |

| Mn | manganese |

| Cu | copper |

| nMgO | nano-magnesium oxide |

| PLLA | left-handed polylactic acid |

| ATZ | alumina toughened zirconia |

| CPC | calcium phosphate ceramics |

| BAG | bioactive glass |

| TTCP | tricalcium phosphate |

| WH | Whitlockite |

| PMMA | polymethyl methacrylate |

| PCL | polycaprolactone |

| EBM | Electron Beam Melting |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| BJ | Binder Jetting |

| PBF | Powder Bed Fusion |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

| MJF | Multi-Jet Fusion |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| DO | diamond-like |

| RD | rhombic dodecahedral |

| PLGA | polylactic-polyhydroxyacetic acid copolymer |

| PA | polyamide |

| Qr | quercetin |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ML | machine learning |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| FE | finite element |

| SSM | statistical shape modeling |

References

- Wang, W.; Yeung, K.W.K. Bone Grafts and Biomaterials Substitutes for Bone Defect Repair: A Review. Bioact. Mater. 2017, 2, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiento, A.R.; Hatt, L.P.; Sanchez Rosenberg, G.; Thompson, K.; Stoddart, M.J. Functional Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration: A Lesson in Complex Biology. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.F.; Dou, H.; Han, S.S.; Tong, H.; Li, X.H. Extraction and three-dimensional model reconstruction of femur based on Mimics software. China Sci. Technol. Inf. 2017, 566, 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, Z.F.; Wang, C.M.; Jin, Z.M. A rapid modeling method for femur based on statistical shape model. J. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 39, 862–869. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, N.; Xi, R.; Wang, X.B. Study on microstructure and properties of additively manufactured NiTi alloy scaffold. J. Shandong Univ. (Health Sci.) 2023, 61, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Onal, E.; Frith, J.; Jurg, M.; Wu, X.; Molotnikov, A. Mechanical Properties and In Vitro Behavior of Additively Manufactured and Functionally Graded Ti6Al4V Porous Scaffolds. Metals 2018, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.F.; Xu, Q.Q. Femur modeling and finite element analysis based on reverse engineering. South. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.P.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Research on Reverse Parametric Femoral Modeling Technology Based on Spatial Transformation and Universal 3D Software. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2022, 373, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Su, P.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.L.; Hu, X.Y.; Lai, Y.L. Three-dimensional Reconstruction and Finite Element Analysis: Supracondylar Femoral Osteotomy has a Positive Effect on the Correction of Genu Varum. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2022, 26, 858–863. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Han, Z.; Hu, K.; Chen, C. Three-Dimensional Reconstructions in the Spine and Surgical Guide Simulation on Digital Images: A Step by Step Approach by Using Mimics-Geomagic-3D Printing Methods. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 569–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.-H.; Li, X.-B.; Phan, K.; Hu, Z.-C.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, J.; Ni, W.-F.; Wu, A.-M. Design of a 3D Navigation Template to Guide the Screw Trajectory in Spine: A Step-by-Step Approach Using Mimics and 3-Matic Software. J. Spine Surg. 2018, 4, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsko, A.; França, R. Modelling Protocol for Root Analogue Dental Implants. US2025275835A1, 4 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.J.; Liu, G.; Li, C.S.; Ye, J.H.; Li, D.C. Design and Mechanical Performance Analysis of Porous Structure for Femoral Stem Based on SLM. Chin. J. Lasers 2022, 49, 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.F.; Wang, L.; Sun, C.N.; Li, D.C.; Jin, Z.M. Microstructure Design for 3D Printed Metal Prosthesis with Variable Modulus. J. Mech. Eng. 2017, 53, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.M.; Wang, J.; Hu, J. Research Progress on the Influence of Pore Structure on the Performance of 3D Printed Bone Tissue Scaffolds. China Plast. 2022, 36, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, L.; Deng, Z.; Lei, H.; Yuan, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.K. Research Progress on the Design and Performance of Porous Titanium Alloy Bone Implants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 2626–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Dong, X.; Jun, J.; Baur, D.A.; Xu, J.; Pan, H.; Xu, X. Bionic Mechanical Design and 3D Printing of Novel Porous Ti6Al4V Implants for Biomedical Applications. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B 2019, 20, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Shao, J.; Wu, X. Novel Negative Poisson’s Ratio Lattice Structures with Enhanced Stiffness and Energy Absorption Capacity. Materials 2018, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmahakhun, S.; Oloyede, A.; Sitthiseripratip, K.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, C. Stiffness and Strength Tailoring of Cobalt Chromium Graded Cellular Structures for Stress-Shielding Reduction. Mater. Des. 2017, 114, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.L.; Lu, X.L.; Huang, C.; Li, F.; Sun, Y.L. Design and Mechanical Properties of Gradient Porous Structure for Titanium Alloy Implants. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2019, 48, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yang, J.; Su, P.; Wang, W. Computer Aided Modeling and Pore Distribution of Bionic Porous Bone Structure. J. Cent. South Univ. 2012, 19, 3492–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, S.M.; Stark, T.; Ruhr, M.; Gutzeit, S. A System Comprising a Foam Structure and a Surgical Fixation Device. EP4574068A2, 25 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, N.; Sadeghian, A.; Kouhi, M.; Haugen, H.J.; Savabi, O.; Nejatidanesh, F. Immunomodulation in Bone Tissue Engineering: Recent Advancements in Scaffold Design and Biological Modifications for Enhanced Regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 1269–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zetao, C.; Travis, K.; Murray, R.Z.; Crawford, R.; Chang, J.; Wu, C.; Xiao, Y. Osteoimmunomodulation for the Development of Advanced Bone Biomaterials. Mater. Today 2016, 19, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.F.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, P.; Liu, H.L.; Li, B.T. Topology Optimization Design Method for Implicit Surface Gradient Porous Structures. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 56, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kök, H.I.; Kick, M.; Akbas, O.; Stammkötter, S.; Greuling, A.; Stiesch, M.; Walther, F.; Junker, P. Reduction of Stress-Shielding and Fatigue-Resistant Dental Implant Design through Topology Optimization and TPMS Lattices. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 165, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, M.; Luo, W.; Gao, L.; Gao, J. Isogeometric Topology Optimization for Innovative Designs of the Reinforced TPMS Unit Cells with Curvy Stiffeners Using T-Splines. Compos. Struct. 2025, 357, 118955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.X.; Li, R.; Tian, Q.H.; Zhou, X.M. Topology Optimization of Porous Structures with Energy Absorption and Load-Bearing Characteristics. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 47, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kang, Y.K.; Kim, S.J. Augment Implant to Which Different Types of Porous Structures Are Applied. US2024024112A1, 25 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.D.; Zhao, L.S.; Wang, Y.K.; Yang, G. A Design Method for Personalized Porous Femoral Stem. CN117814961A, 5 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hollister, S.J. Computational Design and Modeling of Linear and Nonlinear Elastic Tissue Engineering Scaffold Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) Porous Architecture. In Biofabrication and 3D Tissue Modeling; Cho, D.-W., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 77–93. ISBN 978-1-78801-198-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Jin, W.; Liu, W.; Qin, X.; Feng, Y.; Bai, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, J. Selective Laser Melting Fabrication of Porous Ti6Al4V Scaffolds With Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Architectures: Structural Features, Cytocompatibility, and Osteogenesis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 899531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.X.; Jia, P.; Men, Y.T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.M.; Ye, J.D. Design and Optimization of Trabecular Structure Based on Triply Periodic Minimal Surface. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2023, 27, 992–997. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.L.; Gao, J.; Wang, W.; Xiao, J.; Qi, D.H. Design and Analysis of Porous Structure with Deformed Gyroid Unit of Titanium Alloy. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2022, 51, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Tian, C.; Wei, Q.; Gou, X.; Chu, F.; Xu, M.; Qiang, L.; Xu, S. Design and Study of Additively Manufactured Three Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) Structured Porous Titanium Interbody Cage. Heliyon 2024, 10, 38209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, P. Study on the Radial Gradient Variation of Porosity in TPMS Porous Structure and Its Mechanical Properties. Comput. Informatiz. Mech. Syst. 2024, 7, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promoppatum, P.; Sombatmai, A.; Seehanam, S.; Poltue, T.; Karuna, C.; Khrueaduangkhem, S.; Pavasant, P.; Srimaneepong, V.; Sarinnaphakorn, L. Porous-Based Bone Replacement Materials Formed By Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Structure. US2025057656A1, 20 February 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Lu, C.X.; Wen, P.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Y.F. A Multi-Dimensional Spatial Gradient Porous Minimal Surface Bone Implant Material and Its Design Method. CN116059012A, 5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G. A Review of 3D Printed Bone Implants. Micromachines 2022, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, W.; Zhu, M.; Wu, C.; Zhu, Y. Bioceramic-Based Scaffolds with Antibacterial Function for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 18, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tang, X.; Gohil, S.V.; Laurencin, C.T. Biomaterials for Bone Regenerative Engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1268–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlicka, S.; Sobczak, N.; Sobczak, J.J.; Darłak, P.; Ziółkowski, E. Wettability and Reactivity of Liquid Magnesium with a Pure Silver Substrate. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 5689–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmholz, H.; Will, O.; Penate-Medina, T.; Humbert, J.; Damm, T.; Luthringer-Feyerabend, B.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Glüer, C.; Penate-Medina, O. Tissue Responses after Implantation of Biodegradable Mg Alloys Evaluated by Multimodality 3D Micro-Bioimaging in Vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2021, 109, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depboylu, F.N.; Yasa, E.; Poyraz, Ö.; Minguella-Canela, J.; Korkusuz, F.; De Los Santos López, M.A. Titanium Based Bone Implants Production Using Laser Powder Bed Fusion Technology. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 1408–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koju, N.; Niraula, S.; Fotovvati, B. Additively Manufactured Porous Ti6Al4V for Bone Implants: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; He, A.; Su, B.; Lu, X. Additive Manufacturing of Multi-Morphology Graded Titanium Scaffolds for Bone Implant Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.; Al-Rubaie, K.S.; Elbestawi, M.A. The Influence of Selective Laser Melting Defects on the Fatigue Properties of Ti6Al4V Porosity Graded Gyroids for Bone Implants. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 193, 106180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuchuat, J.I.; Manzano, A.S.; Sigot, V.; Miño, G.L.; Decco, O.A. Bone Improvement in Osteoporotic Rabbits Using CoCrMo Implants. Eng. Regen. 2024, 5, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Hong, Q.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Tang, H.; Yang, J.; Qu, X.; Yue, B. Influence of Porosity on Osteogenesis, Bone Growth and Osteointegration in Trabecular Tantalum Scaffolds Fabricated by Additive Manufacturing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1117954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, N.; Brodie, E.G.; Abdal-hay, A.; Alali, A.Q.; Kent, D.; Dargusch, M.S. Additive Manufacturing of Biomimetic Titanium-Tantalum Lattices for Biomedical Implant Applications. Mater. Des. 2022, 218, 110688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.J.; Zhuang, J.J.; Lin, S.Y.; Dong, L.Q.; Cheng, K. Research Progress on Electrochemically Deposited Biofunctional Coatings. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 45, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ren, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y.; Li, P.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y. Dilemmas and Countermeasures of Fe-Based Biomaterials for next-Generation Bone Implants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2034–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Dong, J.; Putra, N.E.; Fratila-Apachitei, L.E.; Zhou, J.; Zadpoor, A.A. Additively Manufactured Function-Tailored Bone Implants Made of Graphene-Containing Biodegradable Metal Matrix Composites. Prog. Mater Sci. 2026, 155, 101517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr Azadani, M.; Zahedi, A.; Bowoto, O.K.; Oladapo, B.I. A Review of Current Challenges and Prospects of Magnesium and Its Alloy for Bone Implant Applications. Prog. Biomater. 2022, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qiao, W.; Liu, X.; Bian, D.; Shen, D.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Kwan, K.Y.H.; Wong, T.M.; Cheung, K.M.C.; et al. Biomimicking Bone–Implant Interface Facilitates the Bioadaption of a New Degradable Magnesium Alloy to the Bone Tissue Microenvironment. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, F.L. Spinal Implant with a Magnesium-Phosphate Three-Dimensional Porosity Structure. US2023120830A1, 20 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Yu, K.; Sun, T.; Jing, X.; Wan, Y.; Chen, K.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, X.; et al. Material–Structure–Function Integrated Additive Manufacturing of Degradable Metallic Bone Implants for Load-Bearing Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Shojaei, A.; Steglich, D.; Höche, D.; Zeller-Plumhoff, B.; Cyron, C.J. Combining Peridynamic and Finite Element Simulations to Capture the Corrosion of Degradable Bone Implants and to Predict Their Residual Strength. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 220, 107143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Shojaei, A.; Höche, D.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Bobaru, F.; Cyron, C.J. Nonlocal Nernst-Planck-Poisson System for Modeling Electrochemical Corrosion in Biodegradable Magnesium Implants. J. Peridynamics Nonlocal Model. 2025, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Baraghtheh, T.; Hermann, A.; Shojaei, A.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Cyron, C.J.; Zeller-Plumhoff, B. Utilizing Computational Modelling to Bridge the Gap between In Vivo and In Vitro Degradation Rates for Mg-xGd Implants. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2023, 4, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller-Plumhoff, B.; Laipple, D.; Slominska, H.; Iskhakova, K.; Longo, E.; Hermann, A.; Flenner, S.; Greving, I.; Storm, M.; Willumeit-Römer, R. Evaluating the Morphology of the Degradation Layer of Pure Magnesium via 3D Imaging at Resolutions below 40 Nm. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4368–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amara, H.; Martinez, D.C.; Shah, F.A.; Loo, A.J.; Emanuelsson, L.; Norlindh, B.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Plocinski, T.; Swieszkowski, W.; Palmquist, A.; et al. Magnesium Implant Degradation Provides Immunomodulatory and Proangiogenic Effects and Attenuates Peri-Implant Fibrosis in Soft Tissues. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 26, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Zahedi, S.A.; Ismail, S.O.; Olawade, D.B. Recent Advances in Biopolymeric Composite Materials: Future Sustainability of Bone-Implant. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senra, M.R.; Marques, M.D.F.V. Synthetic Polymeric Materials for Bone Replacement. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, Q. Bimetallic Ions Regulated PEEK of Bone Implantation for Antibacterial and Osteogenic Activities. Mater. Today Adv. 2021, 12, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Zahedi, S.A.; Ismail, S.O.; Omigbodun, F.T.; Bowoto, O.K.; Olawumi, M.A.; Muhammad, M.A. 3D Printing of PEEK–cHAp Scaffold for Medical Bone Implant. Bio-Des. Manuf. 2021, 4, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Liu, F.W.; Xin, H.; Wu, W.W.; Zhou, G.D.; Jia, X.L.; Li, Y.P.; Cai, B.L.; Tian, L.; Ding, M.C.; et al. A Hot Pressing Method for Nanomorphological Modification of PEEK Surface and the Modified PEEK Material and Its Applications. CN116162273A, 26 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aksu, A.; Vanessa, K.; Frank, R. Implant and Method for Covering Large-Scale Bone Defects for Thorax. JP2025000589A, 7 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Inverardi, N.; Serafim, M.F.; Marzouca, A.; Fujino, K.; Ferreira, M.; Asik, M.D.; Sekar, A.; Muratoglu, O.K.; Oral, E. Synergistic Antibacterial Drug Elution from UHMWPE for Load-Bearing Implants. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 2382–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, L.; Pu, J.; Wang, J.; Fan, C.; Li, Z.; Song, J. Continuous Hyaluronic Acid Supply by a UHMWPE/PEEK Interlocking Scaffold for Metatarsophalangeal Joint Prosthesis Lubricating Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 11704–11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobloth, A.-M.; Checa, S.; Razi, H.; Petersen, A.; Weaver, J.C.; Schmidt-Bleek, K.; Windolf, M.; Tatai, A.Á.; Roth, C.P.; Schaser, K.-D.; et al. Mechanobiologically Optimized 3D Titanium-Mesh Scaffolds Enhance Bone Regeneration in Critical Segmental Defects in Sheep. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaam8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth Swaminathan, S.; Taheri, N.; Becker, L.; Pumberger, M.; Schmidt, H.; Checa, S. Impact of Habitual Flexion on Bone Formation After Spinal Fusion Surgery: An In Silico Study. JOR Spine 2025, 8, e70075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeze, R.J.; Helder, M.N.; Govaert, L.E.; Smit, T.H. Biodegradable Polymers in Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials 2009, 2, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Zan, J.; Qi, F.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Peng, S. nMgO-Incorporated PLLA Bone Scaffolds: Enhanced Crystallinity and Neutralized Acidic Products. Mater. Des. 2019, 174, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omigbodun, F.T.; Osa-Uwagboe, N.; Udu, A.G.; Oladapo, B.I. Leveraging Machine Learning for Optimized Mechanical Properties and 3D Printing of PLA/cHAP for Bone Implant. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perier-Metz, C.; Duda, G.N.; Checa, S. Initial Mechanical Conditions within an Optimized Bone Scaffold Do Not Ensure Bone Regeneration—An in Silico Analysis. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2021, 20, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtiari, H.; Nouri, A.; Tolouei-Rad, M. Impact of 3D Printing Parameters on Static and Fatigue Properties of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Bone Scaffolds. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 186, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari Raj, K.; Gnanavel, S.; Ramalingam, S. Investigation of 3D Printed Biodegradable PLA Orthopedic Screw and Surface Modified with Nanocomposites (Ti–Zr) for Biocompatibility. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 7299–7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budharaju, H.; Suresh, S.; Sekar, M.P.; De Vega, B.; Sethuraman, S.; Sundaramurthi, D.; Kalaskar, D.M. Ceramic Materials for 3D Printing of Biomimetic Bone Scaffolds—Current State-of-the-Art & Future Perspectives. Mater. Des. 2023, 231, 112064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.K.G.; Ramesh, S.; Tasfy, S.F.H.; Lee, K.Y.S. A State-of-the-Art Review on Alumina Toughened Zirconia Ceramic Composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes E Silva, C.C.; König, B.; Carbonari, M.J.; Yoshimoto, M.; Allegrini, S.; Bressiani, J.C. Bone Growth around Silicon Nitride Implants—An Evaluation by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Mater. Charact. 2008, 59, 1339–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Song, C.; Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; Yu, J.; Yuan, F.; Yang, Y. Rational Design and Additive Manufacturing of Alumina-Based Lattice Structures for Bone Implant. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, J. Device for Reconstruction of Bone Defects. SE547315C2, 1 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Drevet, R.; Fauré, J.; Benhayoune, H. Bioactive Calcium Phosphate Coatings for Bone Implant Applications: A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeGeros, R.Z.; Lin, S.; Rohanizadeh, R.; Mijares, D.; LeGeros, J.P. Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics: Preparation, Properties and Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2003, 14, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, D.; Basu, B.; Dubey, A.K. Electrical Stimulation and Piezoelectric Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Khatun, H.; Ali, M.O.; Ali, M.R.; Rahaman, M.; Islam, S.; Ali, Y. Ceramic Coating on Mg Alloy for Enhanced Degradation Resistance as Implant Material. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 479, 130544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, M.; Kim, S.H.; Xu, B.; Amirthalingam, S.; Hwang, N.S.; Lee, J.H. Bioactive Magnesium-Based Whitlockite Ceramic as Bone Cement Additives for Enhancing Osseointegration and Bone Regeneration. Mater. Des. 2023, 229, 111914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslinda, B.S.; Abu, B.B.S.; Ng, M.H.; Mohd, R.B.Y.; Lee, S.S. Polymer-Integrated Ceramic Bone Implant. MY208659A, 22 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huri, G.; Topaloglu, O.; Cikman, M.C. Hybrid, Artificial Bone Tissue Implant Absorbing Mechanical Vibrations, Whose Architectural Structure Imitates Trabecular Bone, Allowing the Saturation of Bone Marrow, Blood, and Nutrients, Supporting Autological Regeneration, Which Can Be Used with Titanium Structures. US20240197958A1, 20 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.J.; Liang, T.Y.; Chen, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, H.S.; Ou, H.L.; Wu, Y.X.; Sun, J.; Lei, S.Y.; Chen, Q.Z. Preparation and Antibacterial Properties of Titanium Alloy Scaffold-Gelatin Composite Drug Delivery System. J. Guangxi Med. Univ. 2023, 40, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Ullah, I.; Liu, X.; Shen, W.; Ding, P.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, T.; Mansoorianfar, M.; Gao, T.; Pei, R. Tannin-Reinforced Iron Substituted Hydroxyapatite Nanorods Functionalized Collagen-Based Composite Nanofibrous Coating as a Cell-Instructive Bone-Implant Interface Scaffold. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 438, 135611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldyerou, A.; Merdji, A.; Aminallah, L.; Roy, S.; Mehboob, H.; Özcan, M. Biomechanical Performance of Ti-PEEK Dental Implants in Bone: An in-Silico Analysis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 134, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, S.; Arazawa, D.; Burley, J.B.; Smith, S.E.; Havener, M.B.; San, A.J.; Long, M.G. Bioactive Soft Tissue Implant and Methods of Manufacture and Use Thereof. US2025213363A1, 3 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Tang, J.R.; Liu, L.Q.; Yang, Y.Q.; Lu, D.; Zhong, B.; Feng, Y.W. A Titanium/Tantalum Composite Porous Bone Defect Repair Scaffold and Its Preparation Method. CN116688242A, 5 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.I.; Viana, F.; Toptan, F.; Geringer, J. Highly Porous Ti as a Bone Substitute: Triboelectrochemical Characterization of Highly Porous Ti against Ti Alloy under Fretting-Corrosion Conditions. Corros. Sci. 2021, 190, 109696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perticarini, L.; Zanon, G.; Rossi, S.M.P.; Benazzo, F.M. Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of a Trabecular TitaniumTM Acetabular Component in Hip Arthroplasty: Results at Minimum 5 Years Follow-Up. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.S.; Liu, X.H.; Chen, X.Z.; Jiang, W.B.; Abdelrehem, A.; Zhang, S.Y.; Chen, M.J.; Yang, C. Customized Skull Base–Temporomandibular Joint Combined Prosthesis with 3D-Printing Fabrication for Craniomaxillofacial Reconstruction: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataee, A.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. A Comparative Study on the Nanoindentation Behavior, Wear Resistance and in Vitro Biocompatibility of SLM Manufactured CP–Ti and EBM Manufactured Ti64 Gyroid Scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2019, 97, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauthle, R.; Van Der Stok, J.; Amin Yavari, S.; Van Humbeeck, J.; Kruth, J.-P.; Zadpoor, A.A.; Weinans, H.; Mulier, M.; Schrooten, J. Additively Manufactured Porous Tantalum Implants. Acta Biomater. 2015, 14, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, D.; Alabort, E.; Reed, R.C. Synthetic Bone: Design by Additive Manufacturing. Acta Biomater. 2019, 97, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannesar, S.; Pournasir, R.M. Selective Laser Melting(Slm) Method-Based Porous Orthopedic and Dental Implants. WO2024161193A1, 8 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Salvatore, F.; Rech, J.; Bajolet, J.; Courbon, J. Effect of Abrasive Flow Machining (AFM) Finish of Selective Laser Melting (SLM) Internal Channels on Fatigue Performance. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 59, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothilakshmi, P.; Poonchezhian, V.P. Additive Manufacturing in Turbomachineries. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 9, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Components by Selective Electron Beam Melting—A Review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 61, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Hao, Y. Additive Manufacturing of Titanium Alloys by Electron Beam Melting: A Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1700842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Zeng, F.; Ren, T.; Guo, W. Efficacy of Bone Defect Therapy Involving Various Surface Treatments of Titanium Alloy Implants: An in Vivo and in Vitro Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Takahashi, H.; Matsugaki, A.; Uemukai, T.; Kogai, Y.; Imagama, T.; Yukata, K.; Nakano, T.; Sakai, T. Novel Nano-Hydroxyapatite Coating of Additively Manufactured Three-Dimensional Porous Implants Improves Bone Ingrowth and Initial Fixation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2023, 111, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Wan, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y. Improved Osseointegration of 3D Printed Ti-6Al-4V Implant with a Hierarchical Micro/Nano Surface Topography: An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandekhoda, M.R.; Mosallanejad, M.H.; Atapour, M.; Iuliano, L.; Saboori, A. Investigation on the Potential of Laser and Electron Beam Additively Manufactured Ti–6Al–4V Components for Orthopedic Applications. Met. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Hoppe, V.; Gąsiorek, J.; Rusińska, M.; Kęszycki, D.; Szczepański, Ł.; Dudek-Wicher, R.; Detyna, J. Corrosion Resistance Characteristics of a Ti-6Al-4V ELI Alloy Fabricated by Electron Beam Melting after the Applied Post-Process Treatment Methods. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 41, 1575–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.L.; Groppo, R.; Bloise, N.; Fassina, L.; Visai, L.; Galati, M.; Iuliano, L.; Mengucci, P. Topological, Mechanical and Biological Properties of Ti6Al4V Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Regeneration Fabricated with Reused Powders via Electron Beam Melting. Materials 2021, 14, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Deng, J.Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, D.W.; Wang, X.Y.; Qin, B.W.; Zeng, B.F.; Lu, Y.D. A Manufacturing Method for Porous Titanium Metatarsal Implant. CN118949124A, 15 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oladapo, B.I.; Zahedi, S.A.; Ismail, S.O. Mechanical Performances of Hip Implant Design and Fabrication with PEEK Composite. Polymer 2021, 227, 123865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassand, C.; Benabed, L.; Benabed, S.; Benabed, J.; Freitag, J.; Siepmann, F.; Soulestin, J.; Siepmann, J. 3D Printed PLGA Implants: APF DDM vs. FDM. J. Controlled Release 2023, 353, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnicz, W.; Augustyniak, M.; Borzyszkowski, P. Mathematical Approach to Design 3D Scaffolds for the 3D Printable Bone Implant. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 41, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, B.; Zahedi, A.; Ismail, S.; Fernando, W.; Ikumapayi, O. 3D-Printed Biomimetic Bone Implant Polymeric Composite Scaffolds. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 4259–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygier, D.; Kujawa, M.; Kowalewski, P. Deposition of Biocompatible Polymers by 3D Printing (FDM) on Titanium Alloy. Polymers 2022, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, J.; He, B.; Lu, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Enhancing Mechanical Performance of Hydroxyapatite-Based Bone Implants via Citric Acid Post-Processing in Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 19, 65020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, M.; Neo, D.W.K.; Rudel, V.; Stautner, M.; Ganser, P.; Zhang, S.X.; Seet, H.L.; Nai, M.L.S. Digital Manufacturing of Personalized Magnesium Implants through Binder Jet Additive Manufacturing and Automated Post Machining. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 3308–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Mao, Y.; Heng, Y.; Tao, J.; Xiang, L.; Qin, X.; Wei, Q. Mechanical Responses of Triply Periodic Minimal Surface Gyroid Lattice Structures Fabricated by Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 2803–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Kuah, K.X.; Prasadh, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.X.; Seet, H.L.; Wong, R.C.W.; Nai, M.L.S. Achieving Biomimetic Porosity and Strength of Bone in Magnesium Scaffolds through Binder Jet Additive Manufacturing. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 166, 214059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, K.K.; Modi, Y.K. Multi Response Optimization for Compressive Strength, Porosity and Dimensional Accuracy of Binder Jetting 3D Printed Ceramic Bone Scaffolds. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 26772–26783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.A.; Mireles, J.; Lin, Y.; Wicker, R.B. Characterization of Ceramic Components Fabricated Using Binder Jetting Additive Manufacturing Technology. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 10559–10564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husna, A.; Ashrafi, S.; Tomal, A.A.; Tuli, N.T.; Bin Rashid, A. Recent Advancements in Stereolithography (SLA) and Their Optimization of Process Parameters for Sustainable Manufacturing. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safonov, A.; Maltsev, E.; Chugunov, S.; Tikhonov, A.; Konev, S.; Evlashin, S.; Popov, D.; Pasko, A.; Akhatov, I. Design and Fabrication of Complex-Shaped Ceramic Bone Implants via 3D Printing Based on Laser Stereolithography. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Zou, B. Development of a Novel Aqueous Hydroxyapatite Suspension for Stereolithography Applied to Bone Tissue Engineering. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 3902–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, C.; Lindner, M.; Zhang, W.; Koczur, K.; Kirsten, A.; Telle, R.; Fischer, H. 3D Printing of Bone Substitute Implants Using Calcium Phosphate and Bioactive Glasses. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 30, 2563–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, M.A.; Asiku, K.S.; Imae, T.; Kawakami, M.; Furukawa, H.; Wu, C.M. Stereolithographic and Molding Fabrications of Hydroxyapatite-Polymer Gels Applicable to Bone Regeneration Materials. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 92, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Zhao, H.; Peng, L.; Sun, Z. A Review of Research Progress in Selective Laser Melting (SLM). Micromachines 2022, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D. Research Progress of 3D Printing Technology in Biomedical Porous Titanium Alloys. Mod. Chem. Res. 2017, 8, 103–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.C.; Kuo, C.N.; Wu, T.H.; Liu, T.Y.; Chen, Y.W.; Guo, X.H.; Huang, J.C. Empirical Rule for Predicting Mechanical Properties of Ti-6Al-4V Bone Implants with Radial-Gradient Porosity Bionic Structures. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.W.; Yuan, H.; Wang, L.Z.; Fan, Y.B. Study on Fatigue Characteristics of Porous Bone Implants with Negative Poisson’s Ratio Effect. J. Med. Biomech. 2021, 36, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Yun, Z.; Zhou, J. Mechanical Performance Analysis of TC4 Titanium Alloy Bionic Bone Implant Unit Structure. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; Gong, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Bai, L. Design and Mechanical Testing of Porous Lattice Structure with Independent Adjustment of Pore Size and Porosity for Bone Implant. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 3240–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.J.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Liu, Y.F. A Design Method for a Mandibular Implant with Functionally Graded and Controllable Vascularization Promotion. CN119908877A, 2 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L.; Arciola, C.R. A Review of the Biomaterials Technologies for Infection-Resistant Surfaces. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8533–8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfang, B.G.; García-Cañete, J.; García-Lasheras, J.; Blanco, A.; Auñón, Á.; Parron-Cambero, R.; Macías-Valcayo, A.; Esteban, J. Orthopedic Implant-Associated Infection by Multidrug Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, D.; Feng, X.; Chen, Z.; Jin, C.; Tan, X.; Xiang, Y.; Jiao, W.; Fang, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. Bioactive Coating with Antibacterial and Anticorrosive Properties Deposited on ZA6-1 Alloy Bone Implant. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 1507–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, Y.; Shi, J.; Yao, X.; Chen, W.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Chu, P.K. Near-Infrared Light II—Assisted Rapid Biofilm Elimination Platform for Bone Implants at Mild Temperature. Biomaterials 2021, 269, 120634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, X.; Wu, W.; Lin, X.C.; Chen, Y.Z. Near-Infrared Light-Triggered Antibacterial and Antioxidant Ti-MXene Bone Implant Material. CN120437384A, 8 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sefa, S.; Wieland, D.C.F.; Helmholz, H.; Zeller-Plumhoff, B.; Wennerberg, A.; Moosmann, J.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Galli, S. Assessing the Long-Term in Vivo Degradation Behavior of Magnesium Alloys—A High Resolution Synchrotron Radiation Micro Computed Tomography Study. Front. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 1, 925471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fang, J.; Wei, P.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Mei, Q.; Ren, F. Cancellous Bone-like Porous Fe@Zn Scaffolds with Core-Shell-Structured Skeletons for Biodegradable Bone Implants. Acta Biomater. 2021, 121, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Gu, C.; Geng, X.; Lin, K.; Xie, Y.; Chen, X. Combined Photothermal and Sonodynamic Therapy Using a 2D Black Phosphorus Nanosheets Loaded Coating for Efficient Bacterial Inhibition and Bone-Implant Integration. Biomaterials 2023, 297, 122122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L.; Arciola, C.R. A Review of the Clinical Implications of Anti-Infective Biomaterials and Infection-Resistant Surfaces. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8018–8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Ge, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Zheng, K.; Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Pan, G.; Geng, D. Engineering Stem Cell Recruitment and Osteoinduction via Bioadhesive Molecular Mimics to Improve Osteoporotic Bone-Implant Integration. Research 2022, 2022, 9823784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Miao, Y.; Liang, H.; Diao, J.; Hao, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Y. 3D-Printed Bioactive Ceramic Scaffolds with Biomimetic Micro/Nano-HAp Surfaces Mediated Cell Fate and Promoted Bone Augmentation of the Bone–Implant Interface in Vivo. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 12, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Shi, J.; Lv, J.; Fang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Lv, Z.; Li, P.; Yao, X.; et al. A Multifunctional Antibacterial Coating on Bone Implants for Osteosarcoma Therapy and Enhanced Osteointegration. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazzi, C.; Mehl, J.; Benamar, M.; Gerhardt, H.; Knaus, P.; Duda, G.N.; Checa, S. External Mechanical Loading Overrules Cell-Cell Mechanical Communication in Sprouting Angiogenesis during Early Bone Regeneration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, M.L.; Nguyen, V.; Hernigou, P.; Flouzat-Lachaniette, C.; Haiat, G. Stress Shielding at the Bone-Implant Interface: Influence of Surface Roughness and of the Bone-Implant Contact Ratio. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Yue, W.; Qin, W.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, G. Research Progress of Bone Grafting: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 4729–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Leary, M.; Bateman, S.; Easton, M. TPMS Designer: A Tool for Generating and Analyzing Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces. Softw. Impacts 2021, 10, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Buehner, U.; Fu, X.; Williamson, T.; Choong, P.; Kim, J. Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network for Interactive Learning of Challenging Musculoskeletal Images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 243, 107875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsilio, L.; Moglia, A.; Manzotti, A.; Cerveri, P. Context-Aware Dual-Task Deep Network for Concurrent Bone Segmentation and Clinical Assessment to Enhance Shoulder Arthroplasty Preoperative Planning. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2025, 6, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, A.; Lozanovski, B.; Downing, D.; Williamson, T.; Kastrati, E.; Shidid, D.; Hill, D.; Buehner, U.; Ryan, S.; Choong, P.F.; et al. Finite Element Analysis of Patient-Specific Additive-Manufactured Implants. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1386816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, C.; Lyu, J.; Cao, S.; Zhang, C.; Ma, X.; Zhao, D. Statistical Shape Modeling of Shape Variability of the Human Distal Tibia: Implication for Implant Design of the Tibial Component for Total Ankle Replacement. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1504897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Suo, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. The Digital Twin: A Potential Solution for the Personalized Diagnosis and Treatment of Musculoskeletal System Diseases. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, S.; Kim, C.; Jang, H.; Lee, S. Toward Digital Twin Development for Implant Placement Planning Using a Parametric Reduced-Order Model. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructive Solid Geometry | Topology Optimization | Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Principles | Constructing complex structures through Boolean operations on basic geometric primitives | Simulation-driven material distribution under specified constraints to achieve optimal performance | Generation of Periodic Porous Structures Based on Implicit Mathematical Surfaces |

| Core Advantages | Simple operation, rapid generation, and easy implementation of gradient structures | Structural lightweighting, optimal mechanical properties, low stress shielding effect | Structures exhibit continuous smoothness, excellent pore connectivity, and high biocompatibility |

| Limitations | Structural connectivity and mechanical properties are inferior to TPMS and topology optimization | Complex design process with high computational costs, requiring integration of manufacturing constraints | Mathematical modeling is relatively complex; gradient design requires integration with other methods |

| Primary Applications | Bionic gradient structures and personalized implants | Lightweight implant design, load-bearing structure optimization, multi-objective performance design | Promotes osseointegration, features highly permeable structures, and mimics biological systems |

| Development Trends | Combined with bioactive coatings, smart materials, and multi-material printing | Multiphysics optimization, biodegradable material design, AI-assisted | Gradient TPMS, topology optimization fusion, multiscale modeling |

| Material Type | Representative Materials | Advantages | Disadvantages | Scope of Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Materials | Titanium and its alloys | Excellent biocompatibility, low elastic modulus, high strength, corrosion resistance | Poor wear resistance, relatively high cost | Load-bearing implants: joint prosthesis stems, bone plates, screws, spinal fusion devices |

| Cobalt-chromium alloys | Exceptional wear resistance, highest strength and hardness, corrosion resistance | Excessively high elastic modulus, relatively poor biocompatibility, allergenic potential | Friction pairs in joint replacements: femoral heads and femoral condyles in artificial hip | |

| Stainless steel (316L) | Low cost, easy machinability, good mechanical properties | Worst corrosion resistance, high elastic modulus, relatively poorest biocompatibility | Primarily used for temporary implants: fracture fixation pins, plates, screws | |

| Biodegradable alloys | Biodegradable and absorbable, elastic modulus closest to bone, degradation products promote osteogenesis | Difficult to control degradation rate, potential hydrogen gas generation during degradation | Fracture internal fixation in non-weight-bearing areas: cardiovascular stents, maxillofacial | |

| Ceramic Materials | Alumina/zirconia | Optimal biocompatibility, highest wear resistance, corrosion resistance | High brittleness, difficult to process and manufacture, high cost | Wear-resistant interfaces in joint replacements: Femoral heads and acetabular liners in hip joints |

| Hydroxyapatite | Excellent osteoconductivity, capable of forming chemical bonds with bone | High brittleness, low strength, unsuitable for load-bearing applications | Surface coatings for metal implants, bone defect fillers | |

| β-tricalcium phosphate | High bioactivity, promotes bone products serve as osteogenic raw materials | High brittleness, low strength, degradation rate requires control | Bone defect filling: Spinal fusion, bone cysts, alveolar ridge augmentation | |

| Polymeric Materials | Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene | Exceptional toughness, good wear resistance, low friction coefficient | Creep behavior, wear particles may induce bone resorption | Wear-bearing surfaces in joint replacements: Acetabular liners, tibial pads |

| Polyether ether ketone | Low elastic modulus, radiolucent, fatigue-resistant, high machinability | Lacks osseointegration capability, average wear resistance, low strength | Spinal fusion devices, non-load-bearing components for joint replacements |

| SLM | EBM | FDM | BJ | SLA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working Principle | Laser selective complete melting of metal powder layers | Electron beam melts preheated metal powder layers in vacuum | Heated nozzles melt and extrude polymer filaments, layering them sequentially | The nozzle sprays binder onto the powder bed, followed by sintering to densify the part | Ultraviolet light selectively cures the flowing slurry and undergoes post-processing |

| Core Advantages | High precision, high density, mechanical properties close to forgings | Low residual stress, fast printing speed, clean vacuum environment | Extremely low cost, simple operation, diverse materials | Extremely fast printing speed, capable of producing highly complex structures, no thermal stress | High resolution, good surface finish, high density |

| Primary Disadvantages | Significant residual stresses, high equipment and material costs, surface requires polishing | Rougher surface, relatively lower precision, extremely high equipment and maintenance costs | Poor precision and surface quality, risk of microbial growth | Complex post-processing, high shrinkage rate, mechanical properties depend on sintering quality | Complex post-processing, Limitations of materials and slurries |

| Typical Materials | Ti6Al4V, CoCr, 316L stainless steel | Ti6Al4V, pure titanium | PEEK, PLA | Titanium powder, calcium phosphate ceramics | Ceramics, polymers |

| Surface Quality | Rough surface (requires post-processing) | Very rough (requires post-processing) | Noticeable layer lines, rough surface | Depends on powder and sintering process | Good surface finish |

| Primary Applications | Load-bearing permanent implants (hip, knee) | Load-bearing permanent implants (large low-stress components) | Surgical guides, planning models, surface coatings | Complex porous bone scaffolds, non-load-bearing implants | Dental, craniofacial, and orthopedic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, B.; Sun, Z.; Tong, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, F. Research Progress on Personalized Bone Implants Based on Additive Manufacturing. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121339

Gao B, Sun Z, Tong Y, Yu H, Wang F. Research Progress on Personalized Bone Implants Based on Additive Manufacturing. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121339

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Bingwei, Zhonghui Sun, Yanquan Tong, Hongtao Yu, and Feng Wang. 2025. "Research Progress on Personalized Bone Implants Based on Additive Manufacturing" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121339

APA StyleGao, B., Sun, Z., Tong, Y., Yu, H., & Wang, F. (2025). Research Progress on Personalized Bone Implants Based on Additive Manufacturing. Micromachines, 16(12), 1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121339