1. Introduction

Arboviruses, including yellow fever virus, dengue virus, and chikungunya virus, remain significant global health concerns, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions [

1,

2,

3]. These viruses often co-circulate and can even co-infect individuals, causing overlapping flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, and muscle pain [

4,

5]. Such clinical similarities make differential diagnosis challenging in endemic areas, frequently leading to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment [

6,

7]. Conventional methods, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), offer high accuracy but require expensive equipment, skilled personnel, and long processing times [

8,

9]. For point-of-care applications, there is an urgent need for rapid, low-cost, and portable diagnostic tools capable of multiplex detection of these viruses.

Multiplexed biosensing has been explored using various platforms, including optical, acoustic, colorimetric, and magnetic bead-based approaches [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. While these methods enable simultaneous detection, their reliance on bulky equipment or complex assay procedures limits their applicability for point-of-care settings. Field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors, on the other hand, offer high sensitivity, rapid and label-free responses, and are compatible with miniaturization and low-cost fabrication. Multiplexing has been demonstrated in various FET architectures, including hydrogel-gated graphene transistors, dual-gate oxide thin-film transistors, and silicon nanowire FETs [

17,

18,

19]. However, these BioFETs often face challenges such as a limited sensing area or additional parasitic components when connecting the external gate structure [

20,

21].

Recently, EGTs have emerged as a promising platform for biosensing [

22,

23]. The use of relatively larger gate electrodes could increase receptor density and enhance the probability of receptor-target binding events [

24,

25,

26]. Furthermore, Si-based EGTs are advantageous over other organic/2D material devices due to their environmental stability, low power consumption, and compatibility with microfabrication processes [

27,

28,

29].

Here, the multiplexed detection of arboviruses using an aptamer-functionalized EGT array is demonstrated. A 4 × 4 Si-based EGT array enabling multiplexed detections was fabricated using a top-down CMOS-compatible process. The electrical characteristics across all 16 devices were sufficiently reproducible to ensure a reliable baseline for multiplexed detection. DNA aptamers specific to YF, DN, and CHK were employed as biorecognition elements. Both individual and multiplexed detections were characterized and evaluated in terms of sensitivity, LOD, and selectivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, VT, USA). Thiol-modified aptamers specific to YF, DN, and CHK were obtained from Bionics (Daejeon, Republic of Korea). YF, West Nile Virus nonstructural protein 1 (WN), and Zika Virus nonstructural protein 1 (ZIK) were purchased from Fitzgerald (Acton, MA, USA). DN and CHK were purchased from Sino Biological (Beijin, China).

2.2. Fabrication of EGTs

EGT arrays were fabricated using a top-down CMOS-compatible process on an 8-inch p-type silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer (10 Ω·cm, (100)).

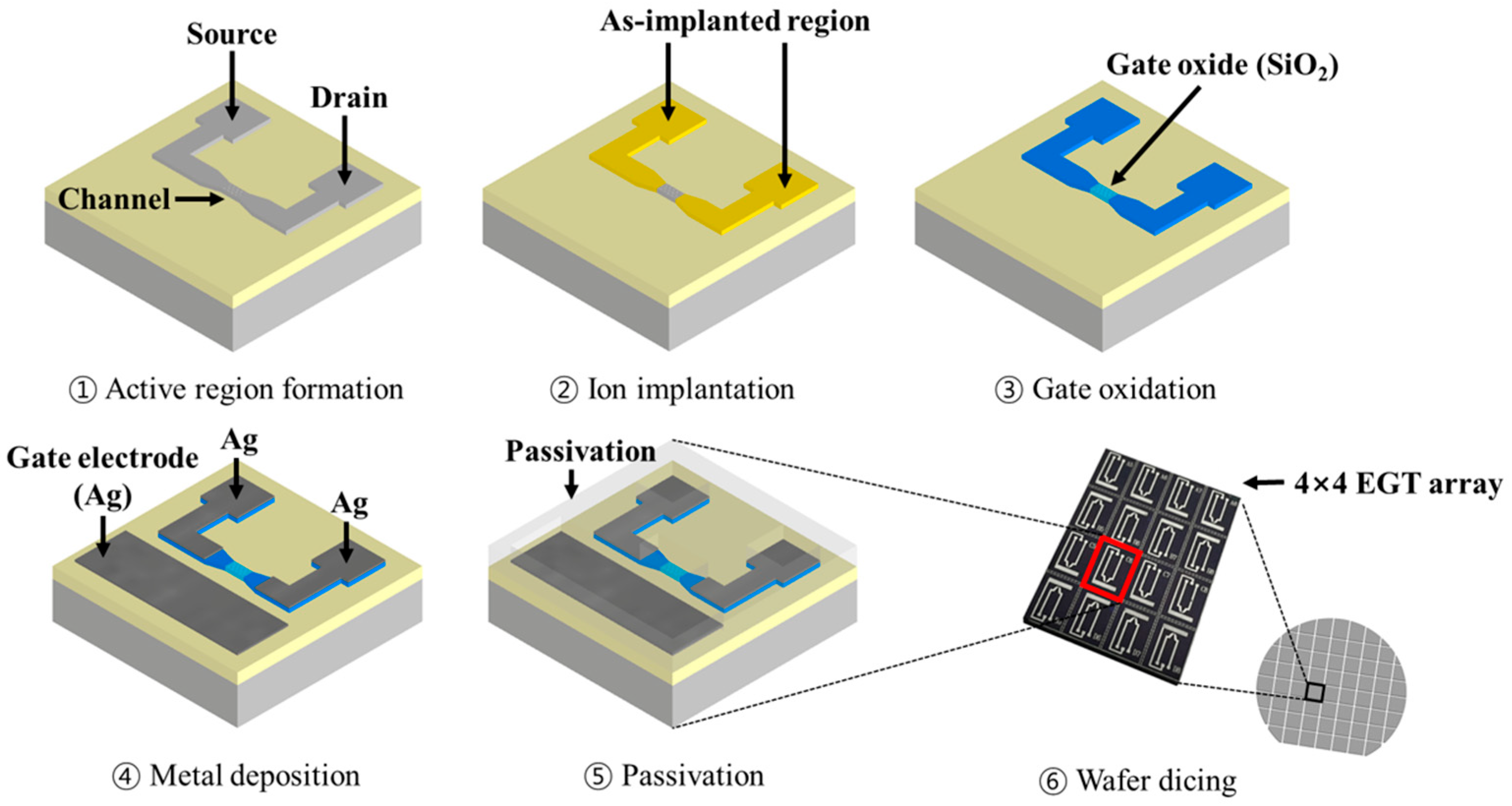

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the EGT fabrication steps. The SOI wafer comprised a 100 nm Si layer and a 400 nm buried oxide. Lithographic patterning of the active regions (source, drain, and channel) using a KrF scanner was performed, followed by inductively coupled plasma reactive-ion etching (ICP-RIE). Arsenic ions at a dose of 5 × 10

15 cm

−2 were implanted into the source and drain and then activated by rapid thermal annealing (RTA, 1000 °C, 20 s). A thin SiO

2 gate dielectric (5 nm) was subsequently grown by thermal oxidation. Then, metal electrodes for the gate, source, and drain interconnects were defined by I-line stepper lithography, followed by a lift-off and the deposition of Ti/Ag (50 nm/500 nm) using e-beam evaporation. Finally, a 3 µm SU-8 layer was patterned as a passivation layer, except for the gate, channel, and contact pads. To enable multiplexing capability, the wafer was diced into multiple dies, each containing 4 × 4 EGTs (16 devices per die).

2.3. Aptamer Functionalization and Detection Protocol

Aptamers functionalized with thiol groups at their termini were exposed to the Ag electrode of the device to bind [

30,

31]. Before aptamer functionalization, the thiol-ended aptamers (in 1 × PBS) were activated by heating at 95 °C for 5 min, then cooling at 4 °C for 30 min. Then, 1 µL of the aptamer solution was dropped onto each EGT gate surface. After one hour, the devices were rinsed with 1 × PBS and deionized water, and then gently dried with N

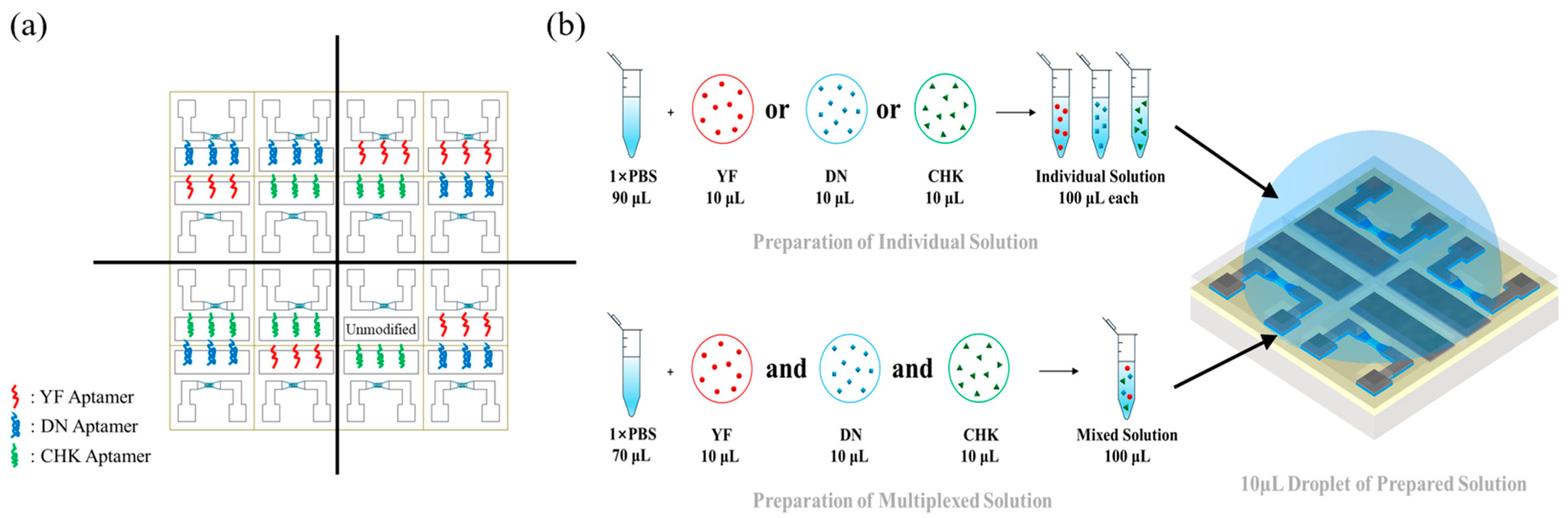

2 gas. Aptamers specific to YF, DN, and CHK were functionalized across 4 × 4 EGT arrays.

Figure 2a shows a representative functionalization of the array, in which devices were coated with three different aptamers to minimize variability during characterization. For individual-target testing, a 10 µL aliquot of a solution containing only one viral protein was added to 90 µL of 1 × PBS. A 10 µL droplet of this solution was then applied to each quadrant of the array and incubated for 30 min. For multiplexed detection, 10 µL of each of the three viral proteins was added with 70 µL of 1 × PBS, and 10 µL of this multiplexed solution was similarly applied to each quadrant and incubated for 30 min, as shown in

Figure 2b.

2.4. Electrical Characterization

Electrical measurements were carried out using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Keithley 4200, Keithley, Solon, OH, USA). The drain current (ID) was measured at a constant drain voltage (VD) of 0.1 V with the source grounded (VS = 0 V). The gate voltage (VG) was applied through the electrolyte (0.01 × PBS buffer solution) and swept from 0 to 1 V with a step size of 0.05 V. The ID was limited to 10−7 A to prevent device degradation during characterization.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Intrinsic Electrical Characteristics

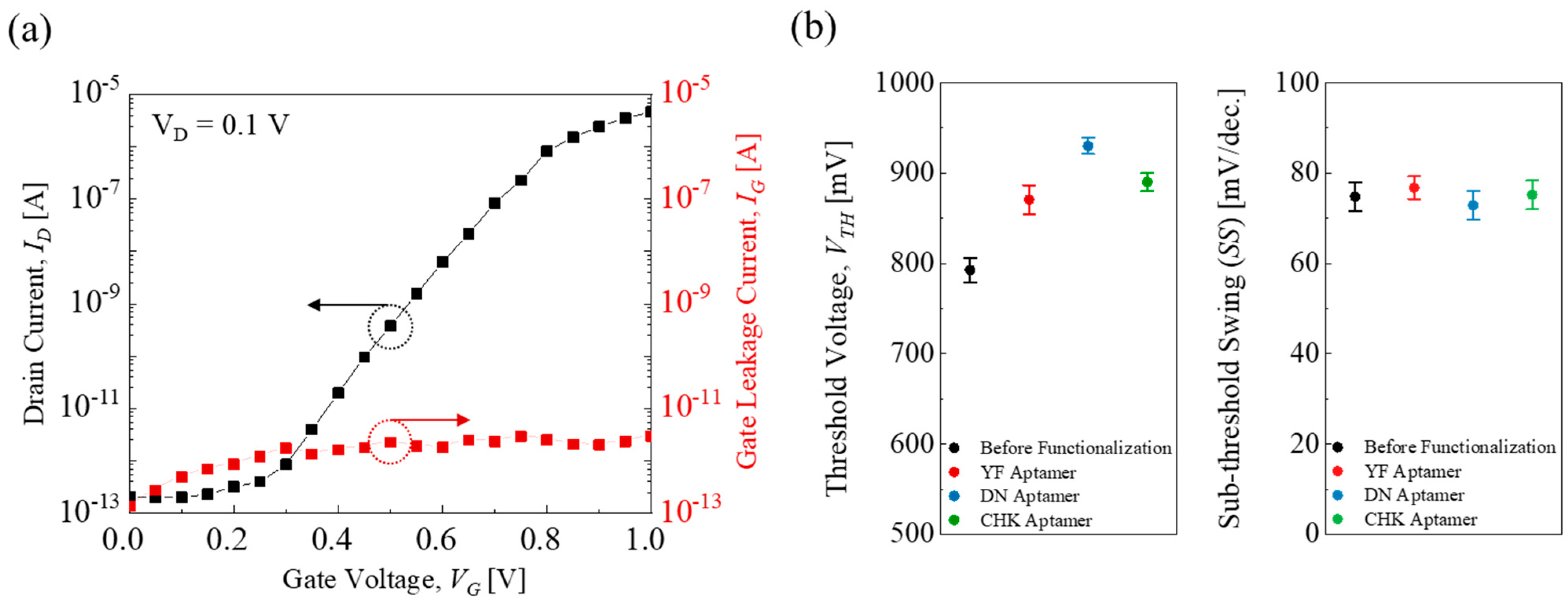

Figure 3a shows a representative transfer curve (

ID–

VG) with a low gate leakage current (

IG) of less than 10 pA.

Figure 3b shows the threshold voltage (

VTH) and sub-threshold swing (

SS ≡ d

VG/dlog (

ID)) in the EGT array. After aptamer functionalization, the transfer curves

ID showed a right shift, indicating a positive shift in threshold voltage due to the formation of a dipole layer induced by the negatively charged aptamer molecules [

25,

32]. The average

VTH values were 792 ± 14 mV, 870 ± 16 mV, 930 ± 9 mV, and 890 ± 10 mV for before, YF-, DN-, and CHK-aptamer functionalization, respectively, as determined from the

gm max method [

33]. In contrast, the

SS values remained nearly unchanged regardless of the surface modification, with an average of 75 ± 3 mV/dec. These results indicate that the EGT array could provide a solid baseline for subsequent multiplexed-sensing characterizations.

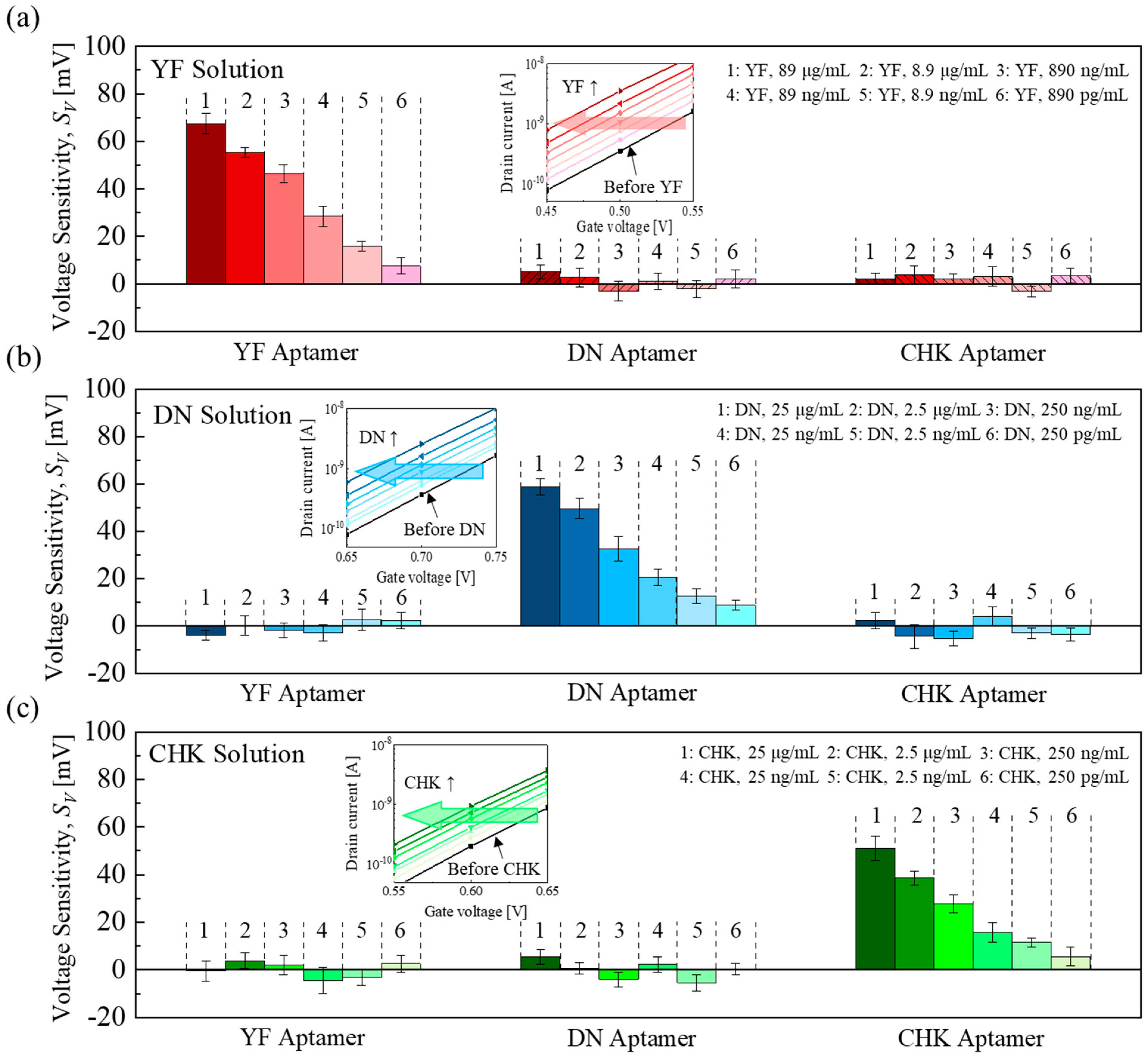

3.2. Individual-Target Responses

The voltage sensitivity (

SV) was defined as the gate voltage shift (

SV =

VG_Aptamer −

VG_Target), where

VG_Aptamer and

VG_Target are the gate voltages before and after target solution exposure, respectively, measured at a drain current of 1 nA.

Figure 4a–c shows the

SV of the aptamer-functionalized EGTs when exposed to the corresponding target solutions (YF: 890 pg/mL–89 μg/mL; DN and CHK: 250 pg/mL–25 μg/mL). Those aptamer–target pairs showed distinct, concentration-dependent responses, while the non-matching pairs showed negligible responses, indicating the high selectivity of the aptamer-functionalized EGT array toward each target analyte.

All the electrical responses show an increase in S

V as the target concentration increases (or a lateral decrease in V

TH in transfer curves). This negative shift arises from the formation of a dipole layer at the gate surface with the aptamer-target conjugate [

25,

28,

34,

35]. The dipole generates a positive effective dipole potential directed toward the gate electrode, which increases the surface potential of the channel. To maintain the same channel potential for a given drain current, this dipole-induced potential must be compensated by lowering the applied gate voltage, resulting in a reduced flat-band voltage (V

FB). Consequently, the transfer curve shifts toward lower gate voltages, appearing as a negative V

TH shift.

Figure 5 shows the

SV and LOD as a function of concentration for each individual-target detection. The experimental data was well fitted with logistic calibration curves, which were subsequently used to calculate the LODs. The fitted equations were

SV = 71.8 × [YF]

0.36/(3.8 × 10

−3 + [YF]

0.36),

SV = 96.5 × [DN]

0.25/(4.3 × 10

−2 + [DN]

0.25), and

SV = 80.6 × [CHK]

0.26/(3.8 × 10

−2 + [CHK]

0.26), respectively. The corresponding blank replicates showed

SV of −3.0 ± 2.3 mV (YF), −3.8 ± 3.1 mV (DN), and −0.9 ± 3.6 mV (CHK), yielding LODs of 38.6 pg/mL for YF, 95.2 pg/mL for DN, and 1.6 ng/mL for CHK, respectively. The blank sample (no target) showed a negligible response, confirming that the observed responses originated from the specific target binding, as shown in the insets of

Figure 5.

3.3. Multiplexed-Targets Responses

To further evaluate the sensing performance under more practical conditions, multiplexed detection was conducted by exposing mixtures of the three target analytes to the aptamer-functionalized EGT array.

Figure 6 shows the

SV for YF-, DN-, and CHK-functionalized EGTs when exposed to multiplexed solutions. The

ID–

VG curves shifted toward negative V

G values with concentration-dependent shifts, similar to those observed in individual detection.

Figure 7 shows the

SV variation with different target solutions obtained in the multiplexed detection. The fitted equations were

SV = 78.2 × [YF]

0.33/(1.4 × 10

−2 + [YF]

0.33),

SV = 59.0 × [DN]

0.37/(2.5 × 10

−3 + [DN]

0.37), and

SV = 63.0 × [CHK]

0.27/(2.5 × 10

−2 + [CHK]

0.27). The corresponding blank replicates showed

SV and LOD of −4.5 ± 3.2 mV and 0.2 ng/mL for YF, −2.2 ± 3.6 mV and 0.6 ng/mL for DN, and −4.2 ± 5.2 mV and 2.82 ng/mL for CHK, respectively.

Figure 8 compares the

SV and the standard deviation (1σ) for individual and multiplexed responses at the highest and lowest concentrations. The multiplexed detection shows a decrease in

SV and an increase in 1σ compared to individual detection. The average reduction in

SV was approximately 22.7%, 4.3%, and 11.8% for YF, DN, and CHK, respectively. When multiple targets are introduced simultaneously onto a sensor surface, they compete for the limited binding sites, thereby reducing sensitivity [

36,

37]. Moreover, the uneven diffusion among coexisting targets could lead to an additional fluctuation in the measured signals.

Table 1 summarizes the sensing performance of various biosensors used for arbovirus detection. In the individual-target detection scheme, the Si-based EGT achieved significantly lower LODs than other electrochemical and optical sensors [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In the multiplexed detection, the Si-based EGT also outperformed colorimetric sensors, showing tens-fold lower LODs. These results demonstrated the superior sensitivity and multiplexing capability of the Si-based EGT array.

3.4. Selectivity Test

To evaluate the specificity of the EGTs, selectivity tests were performed under individual-target conditions, in which each aptamer was exposed to its corresponding target as well as to non-matching targets, as shown in

Figure 9. In each case, only the aptamer–specific target pair produced a distinct response, while negligible signals were observed for non-matching targets, even at relatively high concentrations. Blank samples (1 × PBS without targets) used as negative controls also showed a negligible response. Furthermore, the devices were tested with WN and ZIK arboviruses, yielding negligible responses and confirming the retention of high specificity against their respective targets.

4. Conclusions

The multiplexed detection of arboviruses using Si-based EGT arrays has been evaluated. The fabricated EGTs showed outstanding intrinsic electrical characteristics, including a VTH of ~0.8 V, an SS of 75 mV/dec, and IG below 10 pA, which are essential for ensuring uniform signal response in multiplexed detection. Aptamers specific to YF, DN, and CHK were functionalized across a 4 × 4 EGT array at room temperature prior to exposure to individual or multiplexed target solutions. For individual-target detections, the aptamer–target pairs (YF, DN, CHK) showed negative VTH shifts at varying target concentrations, whereas the non-matching pairs showed negligible VTH change. The extracted LODs were as low as 38.6 pg/mL for YF, 95.2 pg/mL for DN, and 1.6 ng/mL for CHK, respectively. For multiplexed detections, the ID–VG characteristics shifted with increasing target concentration; however, the extracted sensitivities were degraded by 22.7%, 4.3%, and 11.8% for YF, DN, and CHK, respectively, compared to individual detection. The degradation of SV and 1σ affected the LOD values, which were 0.2 ng/mL for YF, 0.6 ng/mL for DN, and 2.8 ng/mL for CHK. However, these LODs are still significantly lower than those of other methods. The specificity test confirms that only the aptamer–specific target pair produced a distinct response, while negligible signals were observed for non-matching targets. These results demonstrate the promise of Si-based EGT arrays as a scalable, cost-effective diagnostic platform for arbovirus detection and point-of-care testing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S. and J.D.; validation, S.S. and J.-S.L.; investigation, S.S. and J.S.; data curation, S.S. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and J.-S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and J.-S.L.; supervision J.-S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00401466, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation), the National R&D Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2023-00266246).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jeong-Soo Lee was employed by the company Innovative General Electronic Sensor Technology (i-GEST) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lim, A.; Shearer, F.M.; Sewalk, K.; Pigott, D.M.; Clarke, J.; Ghouse, A.; Judge, C.; Kang, H.; Messina, J.P.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; et al. The overlapping global distribution of dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.N.; Ploss, A. Emerging mosquito-borne flaviviruses. mBio 2024, 15, e02946-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Dai, X. The incidence and trends of three common flavivirus infections (Dengue, yellow fever, and Zika) from 2011 to 2021. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1458166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.M.A.; Roque, D.G.L.; Policastro, L.R.; Chagas, L.; Giomo, D.B.; Gentil, D.C.D.; Fonseca, V.; Elias, M.C.; Sampaio, S.C.; Giovanetti, M.; et al. Simultaneous Dengue and Chikungunya Coinfection in Endemic Area in Brazil: Clinical Presentation and Implications for Public Health. Res. Sq. 2024. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewara, I.; Chaurasia, D.; Kapoor, G.; Perumal, N.; Bundela, H.P.S.; Dube, S.; Agarwal, A. Insights into the Seroprevalence, Clinical Spectrum, and Laboratory Features of Dengue and Chikungunya Mono-Infections vs. Co-infections During 2022–2023. Cureus 2025, 17, e92410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufi Aiman Sabrina, R.; Muhammad Azami, N.A.; Yap, W.B. Dengue and Flavivirus Cho-Infections: Challenges in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Disease Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madere, F.S.; Andrade da Silva, A.V.; Okeze, E.; Tilley, E.; Grinev, A.; Konduru, K.; García, M.; Rios, M. Flavivirus infections and diagnostic challenges for dengue, West Nile and Zika Viruses. npj Viruses 2025, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkash, O.; Shueb, R.H. Diagnosis of Dengue Infection Using Conventional and Biosensor Based Techniques. Viruses 2015, 7, 5410–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate, D.; Cajigas, S.; Robledo, S.; Muskus, C.; Orozco, J. Genosensors for differential detection of Zika virus. Talanta 2020, 210, 120648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, M.; Belushkin, A.; Cavallini, A.; Kebbi-Beghdadi, C.; Greub, G.; Altug, H. Multiplexed nanoplasmonic biosensor for one-step simultaneous detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Cavalera, S.; Di Nardo, F.; Calabria, D.; Rosati, S.; Simoni, P.; Colitti, B.; Baggiani, C.; Roda, M.; Anfossi, L. Dual lateral flow optical/chemiluminescence immunosensors for the rapid detection of salivary and serum IgA in patients with COVID-19 disease. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 172, 112765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamrunnahar, Q.M.; Haider, F.; Aoni, R.A.; Mou, J.R.; Shifa, S.; Begum, F.; Abdul-Rashid, H.A.; Ahmed, R. Plasmonic Micro-Channel Assisted Photonic Crystal Fiber Based Highly Sensitive Sensor for Multi-Analyte Detection. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, K. Bulk and Surface Acoustic Wave Sensor Arrays for Multi-Analyte Detection: A Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.S.Y.; Thevarajah, T.M.; Chang, S.W.; Khor, S.M. Paper-based multiplexed colorimetric biosensing of cardiac and lipid biomarkers integrated with machine learning for accurate acute myocardial infarction early diagnosis and prognosis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 394, 134403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.Y.; Kwon, J.; Lee, J.H.; Yoon, K.; Shin, Y.B.; Park, K. Rapid and Simultaneous Detection of Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses by a Multiplex Lateral Flow Assay Using Ficolin-1, One of Human Innate Immune Defense Proteins. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 2022, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Vico, J.; Barallat, J.; Abad, L.; Olive-Monllau, R.; Munoz-Pascual, F.X.; Galan Ortega, A.; del Campo, F.J.; Baldrich, E. Dual chronoamperometric detection of enzymatic biomarkers using magnetic beads and a low-cost flow cell. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 69, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bay, H.H.; Vo, R.; Dai, X.; Hsu, H.H.; Mo, Z.; Cao, S.; Li, W.; Omenetto, F.G.; Jiang, X. Hydrogel Gate Graphene Field-Effect Transistors as Multiplexed Biosensors. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 2620–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Son, S.U.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.I.; Kang, T.; Kim, S.; Lim, E.K.; Ko Park, S.H. Rapid and simultaneous multiple detection of a tripledemic using a dual-gate oxide semiconductor thin-film transistor-based immunosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 241, 115700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Xu, L.; Ning, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhang, G.-J. Silicon Nanowire Biosensor for Highly Sensitive and Multiplexed Detection of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Biomarkers in Saliva. Anal. Sci. 2015, 31, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, D.W.C.; Paterno, A.S.; Bertemes-Filho, P. Parasitic Effects on Electrical Bioimpedance Systems: Critical Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeimpekis, I.; Sun, K.; Hu, C.; Thomas, O.; de Planque, M.R.; Chong, H.M.; Morgan, H.; Ashburn, P. Study of parasitic resistance effects in nanowire and nanoribbon biosensors. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Anquetin, G.; Reisberg, S.; Noel, V.; Mattana, G.; Touzeau, J.; Barbault, F.; Pham, M.C.; Piro, B. Triggering the Electrolyte-Gated Organic Field-Effect Transistor output characteristics through gate functionalization using diazonium chemistry: Application to biodetection of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 113, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, B.; Diacci, C.; Makhinia, A.; Savvakis, M.; Gabrielsson, E.O.; Veith, L.; Liu, X.; Strakosas, X.; Simon, D.T. Functionalization of PEDOT:PSS for aptamer-based sensing of IL6 using organic electrochemical transistors. Npj Biosens. 2024, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, M.Y.; Tuccori, E.; Magliulo, M.; Lattanzi, G.; Palazzo, G.; Persaud, K.; Torsi, L. Capacitance-modulated transistor detects odorant binding protein chiral interactions. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchia, E.; Manoli, K.; Holzer, B.; Di Franco, C.; Ghittorelli, M.; Torricelli, F.; Alberga, D.; Mangiatordi, G.F.; Palazzo, G.; Scamarcio, G.; et al. Single-molecule detection with a millimetre-sized transistor. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.; Wustoni, S.; Koklu, A.; Diaz-Galicia, E.; Moser, M.; Hama, A.; Alqahtani, A.A.; Ahmad, A.N.; Alhamlan, F.S.; Shuaib, M.; et al. Rapid single-molecule detection of COVID-19 and MERS antigens via nanobody-functionalized organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Jin, B.; Shin, S.; Do, J.; Son, J.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.S. Highly Sensitive Detection of Urea Using Si Electrolyte-Gated Transistor with Low Power Consumption. Biosensors 2023, 13, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Choi, W.; Shin, S.; Park, J.; Kim, K.; Jin, B.; Lee, J.-S. Lumped-Capacitive Modeling and Sensing Characteristics of an Electrolyte-Gated FET Biosensor for the Detection of the Peanut Allergen. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 168922–168929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Bidoky, F.; Tang, B.; Ma, R.; Jochem, K.S.; Hyun, W.J.; Song, D.; Koester, S.J.; Lodge, T.P.; Frisbie, C.D. Sub-3 V ZnO Electrolyte-Gated Transistors and Circuits with Screen-Printed and Photo-Crosslinked Ion Gel Gate Dielectrics: New Routes to Improved Performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30, 1902028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, M.; Kurt, H. How to make nanobiosensors: Surface modification and characterisation of nanomaterials for biosensing applications. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 49386–49403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Rahimizadeh, K.; Chen, S.; Veedu, R.N. Metallic nanostructure-based aptasensors for robust detection of proteins. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 747–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nano, A.; Furst, A.L.; Hill, M.G.; Barton, J.K. DNA Electrochemistry: Charge-Transport Pathways through DNA Films on Gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11631–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.-S.; White, M.H.; Krutsick, T.J.; Booth, R.V. Modeling of Transconductance Degradation and Extraction of Threshold Voltage in Thin Oxide MOSFETs. Solid-State Electron. 1987, 30, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Luo, X.; Hsing, I.M.; Yan, F. Organic electrochemical transistors integrated in flexible microfluidic systems and used for label-free DNA sensing. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4035–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchia, E.; Sarcina, L.; Picca, R.A.; Manoli, K.; Di Franco, C.; Scamarcio, G.; Torsi, L. Ultra-low HIV-1 p24 detection limits with a bioelectronic sensor. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Walton, S.P. Development of a dual-aptamer-based multiplex protein biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 2663–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, C.V.; Cook, R.L.; Martelly, W.; Gushgari, L.R.; Mohan, M.; Takulapalli, B. Multiplexed proteomic biosensor platform for label-free real-time simultaneous kinetic screening of thousands of protein interactions. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, J.; Kim, E.; Kang, M.; Jeon, J.; Ban, C. Development of an optical sandwich ELONA using a pair of DNA aptamers for yellow fever virus NS1. Talanta 2023, 253, 123979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, N.; Lee, S.; Jang, M.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, C.; Lee, T. Synthesis of Truncated DNA Aptamer and Its Application to an Electrochemical Biosensor Consisting of an Aptamer and a MXene Heterolayer for Yellow Fever Virus. BioChip J. 2023, 18, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.H.; Hayat, A.; Catanante, G.; Latif, U.; Marty, J.L. Development of a portable and disposable NS1 based electrochemical immunosensor for early diagnosis of dengue virus. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1026, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Thangapandi, K.; Mondal, S.; Nanda, A.; Bose, S.; Sanyal, S.; Jana, S.K.; Ghorai, S. Polyaniline Based Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of Dengue Virus Infection. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2020, 12, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Amrutha, M.S.; Srivastava, P.; Sunil, S.; Sai, V.V.R.; Srinivasan, R. Development of a U-bent plastic optical fiber biosensor with plasmonic labels for the detection of chikungunya nonstructural protein 3. Analyst 2021, 146, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Naikoo, U.M.; Khatoon, S.; Pilloton, R.; Narang, J. Aptamer Based on Silver Nanoparticle-Modified Flexible Carbon Ink Printed Electrode for the Electrochemical Detection of Chikungunya Virus. Biosensors 2024, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.W.; de Puig, H.; Tam, J.O.; Gomez-Marquez, J.; Bosch, I.; Hamad-Schifferli, K.; Gehrke, L. Multicolored silver nanoparticles for multiplexed disease diagnostics: Distinguishing dengue, yellow fever, and Ebola viruses. Lab. Chip 2015, 15, 1638–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

A schematic of the fabrication process of the EGT array.

Figure 1.

A schematic of the fabrication process of the EGT array.

Figure 2.

(a) 4 × 4 EGT array with aptamer-functionalized regions. The responses of each target are characterized using five different EGTs in the EGT array. The unmodified EGT in the 4th quadrant is used for the selectivity tests. (b) Detection scheme using individual-target and multiplexed droplets.

Figure 2.

(a) 4 × 4 EGT array with aptamer-functionalized regions. The responses of each target are characterized using five different EGTs in the EGT array. The unmodified EGT in the 4th quadrant is used for the selectivity tests. (b) Detection scheme using individual-target and multiplexed droplets.

Figure 3.

(a) A representative transfer characteristic (IDVG) and gate leakage current (IG) in an EGT device. (b) VTH and SS variation before and after YF-, DN-, and CHK-aptamer functionalization.

Figure 3.

(a) A representative transfer characteristic (IDVG) and gate leakage current (IG) in an EGT device. (b) VTH and SS variation before and after YF-, DN-, and CHK-aptamer functionalization.

Figure 4.

Individual-target detection: SV responses of YF−, DN−, and CHK−aptamer functionalized EGTs to (a) the YF solution, (b) the DN solution, and (c) the CHK solution. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array. Inset: representative transfer curve.

Figure 4.

Individual-target detection: SV responses of YF−, DN−, and CHK−aptamer functionalized EGTs to (a) the YF solution, (b) the DN solution, and (c) the CHK solution. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array. Inset: representative transfer curve.

Figure 5.

Individual-target detection: Logistic fits of SV versus target concentration. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array. Inset: SV of blank sample (1 × PBS without any target) at the LOD using the three-sigma method.

Figure 5.

Individual-target detection: Logistic fits of SV versus target concentration. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array. Inset: SV of blank sample (1 × PBS without any target) at the LOD using the three-sigma method.

Figure 6.

Multiplex detection: SV vs. target concentration for YF, DN, and CHK aptamer-functionalized EGTs. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array.

Figure 6.

Multiplex detection: SV vs. target concentration for YF, DN, and CHK aptamer-functionalized EGTs. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array.

Figure 7.

Multiplexed detection: Logistic fits SV versus target concentration. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array. Inset: SV of blank sample (1 × PBS without any target) at the LOD using the three-sigma method.

Figure 7.

Multiplexed detection: Logistic fits SV versus target concentration. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (±1σ) derived from measurements of five EGTs (n = 5) across the array. Inset: SV of blank sample (1 × PBS without any target) at the LOD using the three-sigma method.

Figure 8.

SV and 1σ variation for the individual and multiplexed detection at the highest (left) and lowest (right) target concentrations.

Figure 8.

SV and 1σ variation for the individual and multiplexed detection at the highest (left) and lowest (right) target concentrations.

Figure 9.

Selectivity tests of aptamer-functionalized EGTs for YF, DN, CHK, ZIK, WN, and blank samples.

Figure 9.

Selectivity tests of aptamer-functionalized EGTs for YF, DN, CHK, ZIK, WN, and blank samples.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of various biosensors for arbovirus detection.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of various biosensors for arbovirus detection.

| Detection Scheme | Biomarker | Method/Device | Dynamic Range | LOD | Ref. |

|---|

| Individual | YFV-NS1 | Optical, EIS/Microplate, Au electrode | 72 ng/mL–9.2 μg/mL

460 pg/mL–46 μg/mL | 39 ng/mL

127 pg/mL | [38]

[39] |

| DENV-NS1 | EIS/SPCE, GCE | 1 ng/mL–200 ng/mL

0.92 ng/mL–92 ng/mL | 0.3 ng/mL

0.36 ng/mL | [40]

[41] |

CHIKV-NS3

CHIKV Antigen | Optical, EIS/POF, PCE | 520 pg/mL–10 μg/mL

100 pg/mL–1 μg/mL | 520 pg/mL

100 pg/mL | [42]

[43] |

YFV-NS1

DENV-NS1

CHIKV-E2 | FET/Si EGT | 890 pg/mL–89μg/mL

250 pg/mL–25 μg/mL

250 pg/mL–25 μg/mL | 38.6 pg/mL

95.2 pg/mL

1.6 ng/mL | This work |

| Multiplexed | YFV-NS1

DENV-NS1

ZEBOV | Optical/Paper Strip | 75 ng/mL–500 ng/mL | 150 ng/mL

for all | [44] |

YFV-NS1

DENV-NS1

CHIKV-E2 | FET/Si EGT | 890 pg/mL–89 μg/mL

250 pg/mL–25 μg/mL

250 pg/mL–25 μg/mL | 0.2 ng/mL

0.6 ng/mL

2.8 ng/mL | This work |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).