Abstract

Machine learning (ML) is a broad term encompassing several methods that allow us to learn from data. These methods may permit large real-world databases to be more rapidly translated to applications to inform patient–provider decision-making. This paper presents a review of articles that discuss the use of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and ML for human blood analysis between the years 2019–2023. The literature review was conducted to identify published research of employed ML linked with FTIR for distinction between pathological and healthy human blood cells. The articles’ search strategy was implemented and studies meeting the eligibility criteria were evaluated. Relevant data related to the study design, statistical methods, and strengths and limitations were identified. A total of 39 publications in the last 5 years (2019–2023) were identified and evaluated for this review. Diverse methods, statistical packages, and approaches were used across the identified studies. The most common methods included support vector machine (SVM) and principal component analysis (PCA) approaches. Most studies applied internal validation and employed more than one algorithm, while only four studies applied one ML algorithm to the data. A wide variety of approaches, algorithms, statistical software, and validation strategies were employed in the application of ML methods. There is a need to ensure that multiple ML approaches are used, the model selection strategy is clearly defined, and both internal and external validation are necessary to be sure that the discrimination of human blood cells is being made with the highest efficient evidence.

1. Introduction

As society continues to evolve, the importance of healthcare as a crucial pillar becomes more evident with each passing day. Providing and improving healthcare services has become an essential target, as it plays a vital role in supporting other societal pillars. Automation and medical devices are an integral part of healthcare services, and their significance has increased with advancements in technology and communication. It is now a prominent time for the healthcare industry to revolutionize the way it delivers services to society, given the rising number of diseases and epidemics.

With the population increasing every second, the demand for laboratory testing has also surged, requiring more health experts to attend to patient analysis and reporting. Particularly, in the case of complex elements such as blood, there is an urgent need for fast and accurate technology to provide initial indications of a patient’s status [1,2].

An adult human body contains approximately five liters of blood, with blood cells comprising nearly 45% of the blood tissue volume. Blood cells are categorized into three types—red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets. In particular, the WBCs include basophils, lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils. RBCs serve as the primary means of transporting oxygen, WBCs play a crucial role in the immune system, fighting against diseases, and platelets aid in the coagulation process, promoting wound healing with scabs. Both physiological and pathological changes can affect the composition of blood, which is clinically a crucial factor to consider [3].

Blood tests have emerged as a direct means of detecting an individual’s health status or diagnosing illnesses. Complete blood cell (CBC) counting is a traditional blood test that involves identifying and counting basic blood cells to examine, monitor, and manage variations in blood. Although this technology has been used since the last century, it has become burdensome for the healthcare sector due to the time, power, and reagents required [4].

It is now time to explore new technologies for analyzing human blood. For instance, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a powerful, low-cost, and fast analysis tool. It can determine the molecular structure of a substance by matching the specific frequency absorbed by the molecule through the transition of the vibration frequency of the bond or group [4]. It has been used for human blood analysis. However, the interpretation of the output FTIR data is, in most cases, performed by human intervention. To overcome this limitation, researchers have joined the use of FTIR spectroscopy analysis to machine learning (ML) for the distinction between pathological and healthy human blood cells.

Thus, this paper aims to perform a review of articles that discuss the use of FTIR spectroscopy and ML for human blood analysis. The resulting tool can benefit healthcare providers as it utilizes precise and specialized equipment. With the use of ML algorithms, the procedure can be automated, replacing the need for specialized equipment.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a broad scientific endeavor that involves developing computational systems to simulate human intelligence and enable problem-solving. ML and deep learning (DL) are subfields of AI, with the study herein presented focusing on ML. It is essential to understand the concept of AI before delving into each of these subfields, including their differences and applications. AI provides a means of automating various tasks without human intervention, making it a sought-after solution in many industries, including homes [5].

ML involves the use of computational tools and methods designed for specific goals to solve problems. In situations where the data input and the desired result are known, but the method to get there is unknown, the ML model can forecast and provide a solution. Therefore, ML presents a different approach from the traditional programming methods where the parameters and approaches are known [6].

ML models undergo data preparation, training, and testing stages. Data preprocessing involves examining and modifying data to improve model comprehension by removing irrelevant information and changing the format. To forecast any value or outcome, the ML model must first be trained using a specified approach. The user responsible for training must provide a substantial amount of data, as well as the expected results for each data point, along with training parameters and settings. This way, the model can learn to understand and interpret the data, making accurate predictions about future outcomes [7,8].

This paper is organized into 5 sections. Section 2 presents the methods used in the review, and how the papers have been collected and selected. Section 3 presents the results obtained from the collected data, which are analyzed and discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 displays the paper’s conclusions and suggestions for future work.

2. Method

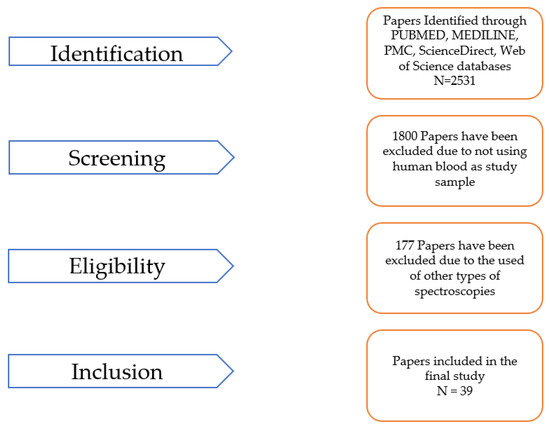

For this paper, a review was conducted using the standard methodology illustrated in (Figure 1). The following databases were searched for peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2019 and 2023: PubMed, MEDLINE, PMC, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science. Before 2019, the number of papers representing ML methods applied to FTIR spectroscopy was low (the authors only identified four papers under this criterium) and, consequently, not significant [9,10,11,12], so this time period was not considered in the search process. After 2019, the number of papers increased dramatically, and the quality of the data showed promising outcomes [13,14], allowing the availability of data to perform a more detailed review analysis. In addition to the database search, relevant articles were manually identified by reviewing the reference lists of the included articles to investigate the effectiveness of the reference lists for the identification of additional, relevant studies. The search terms used were “Machine learning”, “Machine learning AND FTIR OR Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FTIR spectroscopy”, and “Machine learning AND FTIR OR ATR-FTIR spectroscopy AND human blood”. No language restrictions were applied, and Excel software was used to store the articles retrieved from the databases and screen for duplicates. Eligible studies included those that analyzed prospective or retrospective observational data, reported quantitative results for the experiment and evaluation made for the method used. The papers’ data were separated into two tables, whereby in one table (1), the study’s targeting disease, the study type, the sample source methodology, and the FTIR analysis, among other details, are described, and the ML methods, metrics, and validation approach are described in another table (2).

Figure 1.

Schematization of the search and selection process. A total of 39 peer-reviewed articles from 2019 to 2023 were selected and reviewed.

The information extracted from the articles was analyzed descriptively and qualitatively and grouped into categories such as study characteristics, diseases studied, statistical methodologies employed, software packages, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the reported studies. The findings were interpreted based on these categories (Section 3. Results).

3. Results

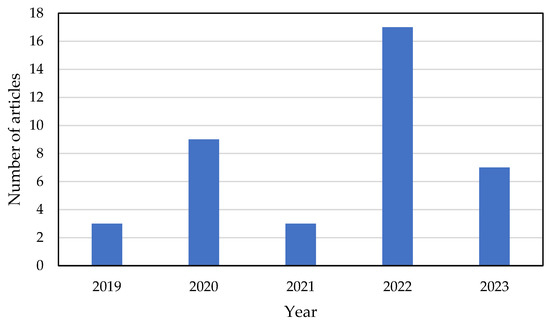

The search methodology described in Section 2 was conducted to identify articles published in the last five years (2019–2023) that combined FTIR spectroscopy and ML methods to distinguish between human blood cells. A total of 39 eligible studies were identified and their characteristics, along with patient data, were summarized based on the keywords used in the search. Figure 2 illustrates that, in the last five years, there has been a growing interest among scientists and researchers in the medical field in the application of AI and ML for FTIR data analysis. These studies have demonstrated the potential of AI and ML to improve healthcare services, particularly in the area of disease diagnosis based on human blood.

Figure 2.

Counting of articles, in the last 5 years, relating to ML and FTIR spectroscopy applied to human blood cells.

3.1. Summary of the Eligible Publications

Table 1 summarizes, with a chronological criterium, the sum-up content data from the 39 selected papers. It includes information about the targeted diseases, the criteria followed in the data collection process, the methodology to collect the samples, and the sample size, as well as the used software and positive and negative outcomes from each reported study.

Table 1.

Summary of the eligible publications.

The presented data (see Figure 2) show that in 2022, the number of papers published on the application of ML and FTIR for diagnosing multiple diseases reached an all-time high. This was particularly evident after the pandemic in 2020, which acted as a catalyst for the adoption of ML and FTIR technologies. The majority of the data sources used in these papers were based on real experimental datasets or designs, accounting for 75% of the total, while the remaining 25% primarily utilized electronic health records (Table 1).

3.2. ML Methods, Metrics, and Internal Validation in the Selected Papers

Table 2 illustrates, also chronologically, the reported ML methods, metrics to evaluate ML, and internal validation procedures followed in the selected studies (according to the papers mentioned in Table 1).

Table 2.

Methods, metrics, and validation in the selected studies.

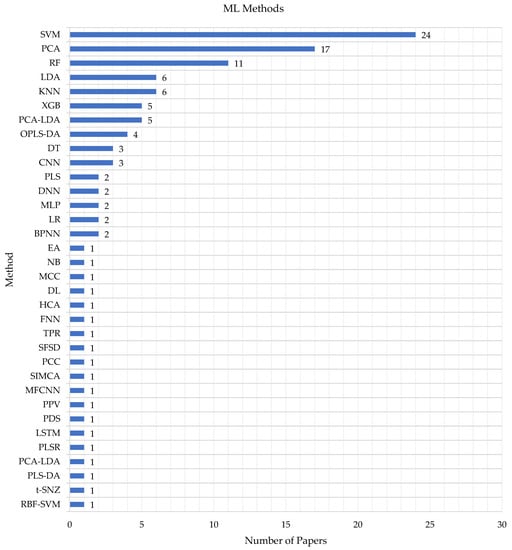

Table 2 outlines the various ML algorithms used for classification or prediction in the selected studies, including SVM (featured in 24 studies), PCA (featured in 17 studies), the KNN and XGB [50] (featured in 6 and 5 studies, respectively), RF [51] (featured in 11 studies), PCA-LDA and OPLS-DA (featured in 5 and 4 studies, respectively), and LDA [52] (featured in 6 studies). The other algorithms/methods presented in the studies were only reported once.

Figure 3 reveals that, in addition to the commonly used algorithms, other methods were employed, such as DT, BPNN, MLP, NB, LR [53], and a novel Bayesian approach, as well as various analytical approaches, including HCA, PCC, and PPV.

Figure 3.

Frequency of the ML methods used in the eligible studies.

The figure shows that the SVMs are frequently used in the biological field—SVMs are one of the most powerful classifiers in ML that can be applied when a dataset is introduced in two classes in a high dimensional feature space, and this is the nature of biological cells.

Most biological genomic data are high-dimensional, heterogeneous, and noisy. This feature makes some methods such as SVMs, PCA, and RFs suitable to be used in the biological field rather than other such as the DL and PCC.

In addition, as summarized in Table 2, almost all the publications (n = 33, 92%) utilized two or more methods, and only less than eight percent (n = 6, 8%) applied a single ML algorithm.

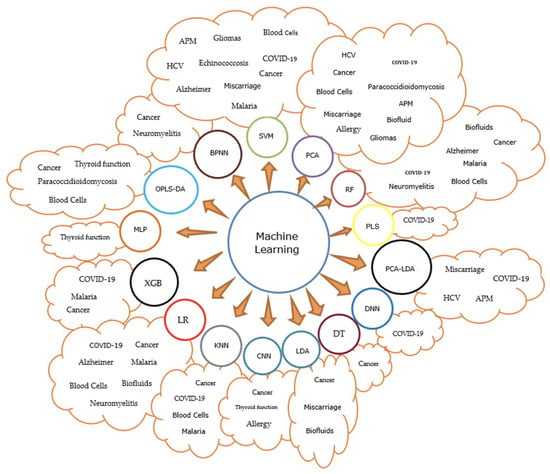

Additionally, further information is presented in Figure 4 to help establish a visual analysis between the type of diseased and the ML methods used for its classification.

Figure 4.

Graphical schematization of the most frequently used ML methods in the FTIR analysis of different diseases.

3.3. Internal and External Validation

The evaluation of the reported studies’ publication quality identified the most common gap in publications as the lack of external validation, which was conducted by only two studies [13,49]. Twelve of the reported studies predefined the success criteria for model performance [15,19,22,25,26,36,38,41,43,47,48] and nine studies discussed the generalizability of the model [14,17,20,27,29,33,35,42,46]. All the studies, except one [37], discussed the balance between model accuracy and model sensitivity and specificity.

3.4. Strengths and Weaknesses

The authors of the selected articles noted both strengths and weaknesses in the used ML methods. Overall, the simplicity and low complexity of ML methods were recognized as strengths, as they are powerful and efficient tools for handling large datasets. However, one article highlighted that the effectiveness of ML is highly dependent on proper method selection and parameter optimization and that these steps are essential for obtaining accurate estimates [25].

Even with careful planning and despite their advantages, ML approaches still present several limitations, which warrant attention in future studies. Overfitting was identified as a weakness, which can occur when too much detail is included in the method. Other limitations stem from the quality and availability of the data sources used, such as incomplete variable sets or missing data, which can negatively affect model development and performance. Retrospective database studies were identified as particularly vulnerable to the lack of relevant variables, as researchers are limited to recorded data. Finally, the lack of external validation was noted as a limitation of the studies reviewed in this analysis.

4. Discussion

In this review, we examined the methods and approaches used for ML in the context of observational datasets related to the FTIR or ATR-FTIR analysis of human blood cell conditions. While ML methods have been applied more broadly in recent years, our review focused specifically on studies that utilized FTIR or ATR-FTIR spectroscopies and human blood cells, and therefore, our findings may not be applicable to all ML methods. Our primary objective was to explore the potential of ML methods in distinguishing between healthy and pathological cells on a large scale, not limited to a specific disease, to improve healthcare services and provide physicians with reliable evidence applicable to individual patients. This review aims to provide guidance and best practices for the use of ML methods in discriminating between human blood cells, with the goal of improving their effectiveness and increasing their use in generating data and models for healthcare decision-making. The used methods represent a single point on a potentially wide distribution, meaning that any cell spectrum could fall anywhere within that distribution and may be far from the point that distinguishes between healthy and pathological conditions.

Multiple algorithms were used in the majority of the articles, although in some articles single modeling methodologies were considered; this underscores the importance of selecting and developing ML algorithms, particularly considering recent advances in analytics capabilities.

The FTIR analysis presented in Table 1 shows that all the studies discussed utilized the mid-IR domain, specifically the wavelength range of 400 to 4000 cm−1, with spectral resolutions ranging between 2–8 cm−1 being the most common 4 cm−1. While the basic IR parameters were consistent across the studies, the analysis varied in terms of the preprocessed spectrum region, i.e., the main interest regions. This variation is primarily influenced by the specific wavelength being targeted, which in turn affects the intensity band observed in the selected preprocessed spectrum region.

While a single model may sometimes produce accurate results that match the data well, creative methods can be used to support the model’s certainty. It is advised that this be adopted as a best practice in the future and be used as an extra criterion to evaluate the caliber of research among ML algorithms.

The methods that were used in each publication performed differently based on many inputs, varied in the metrics and internal validations, and gave different results describing the potential and significance of using these methods in the medical field.

SVMs and PCA are the two ML most frequently used methods in the biological field, with SVMs being used in 25 papers among the 39 selected ones and PCA being used in 17 papers. Other methods such as RFs, LDA, and XGB also play a big part in the biology field as methods for assessing biological cells and enhancing outcomes.

Cancer seems to be the main targeted disease in order to develop a method that can be used to detect the carcinogenic cells on the nuclear stage (10 types of ML methods were used in the 39 selected papers), followed by inflammatory diseases in general.

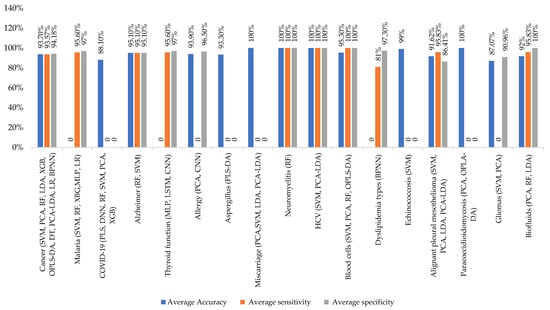

The classification average accuracy of identification/distinction between FTIR spectra was found to be 93.7% for cancer, 88.10% for COVID-19, 95.10% for Alzheimer’s disease, 93.90% for allergies, 93.30% for Aspergillus, 100% for miscarriage, neuromyelitis, hepatitis C virus, and Paracoccidioidomycosis, 95.3% for blood cells, 99% for echinococcosis, 91.62% for malignant pleural mesothelioma, 87.07% for gliomas, and 91.62% for biofluids (calculated from the data presented in Table 1).

These findings demonstrate the power of basic ML algorithms as applied intelligence tools to distinguish the complex vibrational spectra of, for example, cancer patients from those of healthy patients. These experimental methods show promise as a valid and efficient liquid biopsy for artificial-intelligence-assisted early cancer screening, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Metrics to evaluate the average ML performance in FTIR applied to different diseases. For each disease, the most common ML methods are reported. The blue column represents the average accuracy, the red column represents the average sensitivity, and the green column represents the average specificity.

By combining FTIR spectroscopy with deep learning, it was possible not only to differentiate between allergic and healthy patients but also to stratify and treat patients, indicating its potential for monitoring the efficacy of SIT in individual patients. However, further investigation is needed to determine whether FTIR-spectroscopic-based identification of allergic status is limited to adults or can also be applied to samples collected from other groups, such as children.

The classification process utilizing PLS and DNNs [54] algorithms shows promising results in distinguishing COVID-19 patients from healthy individuals. The extraction process revealed numerous features of the FTIR signal and combining all these features achieved effective accuracy values.

The results indicate that using these 16 features could be valuable in accurately classifying COVID-19 patients and healthy subjects. For the proposed method for predicting the biological contour shape, the method enables the application of genomic selection to rice grain shape improvement as depicted in Figure 5.

Moreover, Figure 5 shows that the neural network models have successfully identified unique infrared absorption spectra in many diseases, such as cancer, allergies, thyroid function, and COVID-19. These spectra can effectively distinguish between malignant and benign breast tissues.

The ML classification that used SVMs [55] to distinguish between pathological and healthy patients for multiple diseases such as malaria and Alzheimer’s disease and miscarriage achieved sensitivity between 95–100% (with three false negatives for each disease) and specificity between 95–97% (with two false positives for each disease). The method had good predictability with a low error rate and can be sufficiently accurate for the analysis of blood cells like the reference method. The suggested method is simple, fast, economical and does not require pollutant solvents and expensive equipment. It is worth noting that one of the false positives was due to a Plasmodium species other than Plasmodium falciparum or Plasmodium vivax, which was not detected by the PCR primers employed. Therefore, the results may actually be better than reported. The study also demonstrated that ATR-FTIR spectroscopy can be a reliable and efficient diagnostic tool for miscarriage, with the potential to be used at the point of care in tropical field conditions. The spectra can be analyzed via a cloud-based system, which makes it easily accessible for mass screening. This approach is highly sensitive, selective, portable, and requires low logistics, which makes it a potentially outstanding tool for malaria elimination programs. Currently, the experimental program is focused on reducing the sample requirements to fingerpick volumes [8].

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented a review of articles that discuss the use of FTIR spectroscopy combined with ML for human blood analysis between the years 2019–2023.

The reported implementation of ML techniques covered a wide range of approaches, methods, statistical software, and validation strategies. Based on these findings, it is essential to assess and compare several modeling approaches when creating ML-based models for correctly evaluating FTIR data, aimed at diagnosing human blood, which calls for the highest research standards. Models should be assessed using precise criteria before being chosen.

There is potential to apply FTIR-based ML diagnosis to aid clinical decisions as a triage method for human blood cell discrimination, extending to early cancer screening, health monitoring, disease detection, and food safety. Identifying early stages or referral decisions is essential, usually unmet by the current diagnostic pathway. That level of proof has been attained by a sizable number of studies that distinguish between abnormal and healthy human blood cells. Moreover, considering data availability, power computing, and access to AI tools, it should be expected that there will be a high increase in the use of ML and DL approaches for human blood analysis in the future years due to the advantages they provide.

This fast method is highly important and critical for many patients. It is effective for both accessible and inaccessible diseases in which lab tests are normally useless. Thus, it could serve as a significant and objective diagnostic tool that will assist physicians in increasing their diagnostic accuracy of the etiology of diseases, especially for inaccessible patients. Before ML approaches are used to analyze blood cells, we need additional field validation in other study sites with different parasite populations and an in-depth evaluation of the biological basis of blood cells.

ML approaches still present several limitations, which warrant attention in future studies using these methods. Overfitting has been identified as a weakness, which can occur when too much detail is included in the method. Other limitations stem from the quality and availability of the used data sources, such as incomplete variable sets or missing data, which can negatively affect the model’s development and performance. Retrospective database studies were identified as particularly vulnerable to the lack of relevant variables, as researchers are limited to recorded data. Moreover, the lack of external validation was noted as a limitation of the studies reviewed in this analysis. Thus, improving the classification algorithms and model training on larger datasets could also improve specificity and sensitivity, as well as looking up details to increase the potential of FTIR spectroscopy and ML application in the biological field [56,57,58,59]. Finally, the output from this paper—apart from the description of the most used ML techniques and corresponding metrics in the biological field—could be a strong basis for further developments, focusing the application of these methodologies on human blood cell analysis [60], even targeting their application in microfluidic, lab-on-a-chip [61,62,63,64], or other point-of-care miniaturized devices [65], among others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and V.C.; methodology, A.F., S.O.C. and V.C.; investigation, A.F., V.C., S.O.C. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.; writing—review and editing, S.O.C., G.M. and V.C.; supervision, V.C., S.O.C. and G.M.; funding acquisition, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the R&D Unit Project Scope: UIDB/04436/2020, UIDB/05549/2020 and UIDP/05549/2020 funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. (FCT). S.O.C. thanks the FCT for her 2020. 00215.CEECIND contract funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Talukdar, K.; Bora, K.; Mahanta, L.B.; Das, A.K. A comparative assessment of deep object detection models for blood smear analysis. Tissue Cell 2022, 76, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, J.; Nechyporenko, A.; Frohme, M.; Hufert, F.T.; Schulze, K. Examination of blood samples using deep learning and mobile microscopy. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Lin, J.W. Complete Blood Cell Detection and Counting Based on Deep Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzam, M.B.; Tayyib, N.; Alshawwa, S.Z.; Ahmed, M.K. Nursing Care Systematization with Case-Based Reasoning and Artificial Intelligence. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1959371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, L. Detection of WBC, RBC, and Platelets in Blood Samples Using Deep Learning. Biomed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1499546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Meng, F.; Feng, M.; Zhao, X.; Gao, C.; Luo, J. Identification of biomarkers by machine learning classifiers to assist diagnose rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2022, 24, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, F.; Chen, C.; Yan, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Lv, X. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy combined with deep learning and data enhancement for quick diagnosis of abnormal thyroid function. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 32, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.-W.; Mak, S.-H.; Goh, B.-H.; Lee, W.-L. The Convergence of FTIR and EVs: Emergence Strategy for Non-Invasive Cancer Markers Discovery. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajjar, K.; Trevisan, J.; Owens, G.; Keating, P.J.; Wood, N.J.; Stringfellow, H.F.; Martin-Hirsch, P.L.; Martin, F.L. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy coupled with a classification machine for the analysis of blood plasma or serum: A novel diagnostic approach for ovarian cancer. Analyst 2013, 138, 3917–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.I.; Broadhurst, D.; Goodacre, R. Rapid and quantitative detection of the microbial spoilage of beef by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and machine learning. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 514, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitole, L.; Steffens, F.; Krüger TP, J.; Meyer, D. Mid-ATR-FTIR spectroscopic profiling of HIV/AIDS sera for novel systems diagnostics in global health. OMICS 2014, 18, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, L.D.; Buteau, S.; Hames, S.G.; Thompson, L.M.; Hall, D.S.; Dahn, J.R. A New Method for Determining the Concentration of Electrolyte Components in Lithium-Ion Cells, Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Machine Learning. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A256–A262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanga, E.P.; Minja, E.G.; Mrimi, E.; Jiménez, M.G.; Swai, J.K.; Abbasi, S.; Ngowo, H.S.; Siria, D.J.; Mapua, S.; Stica, C.; et al. Detection of malaria parasites in dried human blood spots using mid-infrared spectroscopy and logistic regression analysis. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heraud, P.; Chatchawal, P.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Tippayawat, P.; Doerig, C.; Jearanaikoon, P.; Perez-Guaita, D.; Wood, B.R. Infrared spectroscopy coupled to cloud-based data management as a tool to diagnose malaria: A pilot study in a malaria-endemic country. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 348–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toraman, S.; Girgin, M.; Üstündağ, B.; Türkoğlu, İ. Classification of the likelihood of colon cancer with machine learning techniques using FTIR signals obtained from plasma. Turk. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2019, 27, 1765–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaria, A.H.; Rosen, G.B.; Lapidot, I.; Rich, D.H.; Mordechai, S.; Kapelushnik, J.; Huleihel, M.; Salman, A. Rapid diagnosis of infection etiology in febrile pediatric oncology patients using infrared spectroscopy of leukocytes. J. Biophotonics 2020, 13, e201900215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Lapidot, I.; Shufan, E.; Agbaria, A.H.; Katz, B.-S.P.; Mordechai, S. Potential of infrared microscopy to differentiate between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s diseases using peripheral blood samples and machine learning algorithms. J. Biomed Opt. 2020, 25, 046501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleken, Z.; Kuruca, S.E.; Ünübol, B.; Toraman, S.; Bilici, R.; Sarıbal, D.; Gunduz, O.; Depciuch, J. Biochemical assay and spectroscopic analysis of oxidative/antioxidative parameters in the blood and serum of substance use disorders patients. A methodological comparison study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 240, 118625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, E.; Bağcıoğlu, M.; Garner-Spitzer, E.; Wiedermann, U.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Schabussova, I. Machine learning-empowered ftir spectroscopy serum analysis stratifies healthy, allergic, and sit-treated mice and humans. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaria, A.H.; Beck, G.; Lapidot, I.; Rich, D.H.; Kapelushnik, J.; Mordechai, S.; Salman, A.; Huleihel, M. Diagnosis of inaccessible infections using infrared microscopy of white blood cells and machine learning algorithms. Analyst 2020, 145, 6955–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Oh, S.; Hong, S.; Kang, M.; Kang, D.; Ji, Y.-J.; Choi, B.H.; Kang, K.-W.; Jeong, H.; Park, Y.; et al. Early-Stage Lung Cancer Diagnosis by Deep Learning-Based Spectroscopic Analysis of Circulating Exosomes. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5435–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guleken, Z.; Ünübol, B.; Bilici, R.; Sarıbal, D.; Toraman, S.; Gündüz, O.; Kuruca, S.E. Investigation of the discrimination and characterization of blood serum structure in patients with opioid use disorder using IR spectroscopy and PCA-LDA analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal. 2020, 190, 113553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, H.J.; Bonnier, F.; McIntyre, J.; Parachalil, D.R. Quantitative analysis of human blood serum using vibrational spectroscopy. Clin. Spectrosc. 2020, 2, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theakstone, A.G.; Rinaldi, C.; Butler, H.J.; Cameron, J.M.; Confield, L.R.; Rutherford, S.H.; Sala, A.; Sangamnerkar, S.; Baker, M.J. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy of biofluids: A practical approach. Transl. Biophotonics 2021, 3, e202000025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Meng, C.; Qu, H.; Cheng, C.; Yang, B.; Gao, R.; Lv, X. Human serum mid-infrared spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms for rapid detection of gliomas. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkadi, O.A.; Hassan, R.; Elanany, M.; Byrne, H.J.; Ramadan, M.A. Identification of Aspergillus species in human blood plasma by infrared spectroscopy and machine learning. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 248, 119259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, R.C.; Sayat, A.J.; Atienza, A.N.; Danganan, J.L.; Ramos, M.R.; Fellizar, A.; Notarte, K.I.; Angeles, L.M.; Bangaoil, R.; Santillan, A.; et al. Detection of breast cancer by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy using artificial neural networks. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthamacumaran, A.; Elouatik, S.; Abdouh, M.; Berteau-Rainville, M.; Gao, Z.-H.; Arena, G. Machine learning characterization of cancer patients-derived extracellular vesicles using vibrational spectroscopies: Results from a pilot study. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 12737–12753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleken, Z.; Tok, Y.T.; Jakubczyk, P.; Paja, W.; Pancerz, K.; Shpotyuk, Y.; Cebulski, J.; Depciuch, J. Development of novel spectroscopic and machine learning methods for the measurement of periodic changes in COVID-19 antibody level. Measurement 2022, 196, 111258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasymov, O.K.; Aydemirova, A.H.; Melikova, L.A.; Aliyev, J.A. Artificial intelligence to classify human lung carcinoma using blood plasma FTIR spectra. Appl. Comput. Math. 2022, 20, 277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Xie, F.; Yin, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, G.; Wang, S. Breast cancer early detection by using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy combined with different classification algorithms. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 283, 121715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praja, R.K.; Wongwattanakul, M.; Tippayawat, P.; Phoksawat, W.; Jumnainsong, A.; Sornkayasit, K.; Leelayuwat, C. Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy Discriminates the Elderly with a Low and High Percentage of Pathogenic CD4+ T Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleken, Z.; Jakubczyk, P.; Wiesław, P.; Krzysztof, P.; Bulut, H.; Öten, E.; Depciuch, J.; Tarhan, N. Characterization of Covid-19 infected pregnant women sera using laboratory indexes, vibrational spectroscopy, and machine learning classifications. Talanta 2022, 237, 122916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, Y.; Gebelin, M.; de Sèze, J.; Patte-Mensah, C.; Marcou, G.; Varnek, A.; Mensah-Nyagan, A.-G.; Hellwig, P.; Collongues, N. Rapid Discrimination of Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis Using Machine Learning on Infrared Spectra of Sera. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Wei, G.; Chen, W.; Lei, C.; Xu, C.; Guan, Y.; Ji, T.; Wang, F.; Liu, H. Fast and Deep Diagnosis Using Blood-Based ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for Digestive Tract Cancers. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Santo, R.; Vaccaro, M.; Romanò, S.; Di Giacinto, F.; Papi, M.; Rapaccini, G.L.; De Spirito, M.; Miele, L.; Basile, U.; Ciasca, G. Machine Learning-Assisted FTIR Analysis of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles for Cancer Liquid Biopsy. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guleken, Z.; Bahat, P.Y.; Toto, F.; Bulut, H.; Jakubczyk, P.; Cebulski, J.; Paja, W.; Pancerz, K.; Wosiak, A.; Depciuch, J. Blood serum lipid profiling may improve the management of recurrent miscarriage: A combination of machine learning of mid-infrared spectra and biochemical assays. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 8341–8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, F. Rapid and sensitive detection of esophageal cancer by FTIR spectroscopy of serum and plasma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sun, C.; Yue, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Shabbir, S.; Zou, L.; Lu, W.; Wang, W.; Xie, Z.; et al. Screening ovarian cancers with Raman spectroscopy of blood plasma coupled with machine learning data processing. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 265, 120355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, A.; Scroferneker, M.L.; Pereira, B.A.S.; de Souza, N.M.P.; Cavalcante, R.D.S.; Mendes, R.P.; Corbellini, V.A. Using infrared spectroscopy of serum and chemometrics for diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis. J. Pharm. Biomed Anal. 2022, 221, 115021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonar, D.; Severcan, M.; Gurbanov, R.; Sandal, A.; Yilmaz, U.; Emri, S.; Severcan, F. Rapid diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma and its discrimination from lung cancer and benign exudative effusions using blood serum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, G.; Lv, G.; Yin, L.; Lv, X. Rapid discrimination of hepatic echinococcosis patients’ serum using vibrational spectroscopy combined with support vector machines. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, N.M.P.; Machado, B.H.; Koche, A.; da Silva Furtado, L.B.F.; Becker, D.; Corbellini, V.A.; Rieger, A. Discrimination of dyslipidemia types with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and chemometrics associated with multivariate analysis of the lipid profile, anthropometric, and pro-inflammatory biomarkers. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 540, 117231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, N.M.P.; Machado, B.H.; Padoin, L.V.; Prá, D.; Fay, A.P.; Corbellini, V.A.; Rieger, A. Rapid and low-cost liquid biopsy with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to discriminate the molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Talanta 2023, 254, 123858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Dawuti, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, R.; Zhou, J.; Lin, R.; Lü, G. Rapid Detection of Serological Biomarkers in Gallbladder Carcinoma Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Combined with Machine Learning. Talanta 2023, 259, 124457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, F.; Du, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, B.; Zuo, E.; Xiao, M.; Lv, X.; Liu, P. Raman spectroscopy and FTIR spectroscopy fusion technology combined with deep learning: A novel cancer prediction method. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 285, 121839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalhete, L.; Araújo, R.; Ferreira, A.; Calado, C.R. Label-free discrimination of T and B lymphocyte activation based on vibrational spectroscopy—A machine learning approach. Vib. Spectrosc. 2023, 126, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, N.M.P.; Machado, B.H.; Koche, A.; da Silva Furtado, L.B.F.; Becker, D.; Corbellini, V.A.; Rieger, A. Detection of metabolic syndrome with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and chemometrics in blood plasma. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 288, 122135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Naveed, A.; Hussain, I.; Qazi, J. Use of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to differentiate between cirrhotic/non-cirrhotic HCV patients. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 42, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 13–17, pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.C.; Liong, C.Y.; Jemain, A.A. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) for classification of high-dimensional (HD) data: A review of contemporary practice strategies and knowledge gaps. Analyst 2018, 143, 3526–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, K.M.; Reinke, S.N.; Broadhurst, D.I. A comparative evaluation of the generalised predictive ability of eight machine learning algorithms across ten clinical metabolomics data sets for binary classification. Metabolomics 2019, 15, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y. Statistical Learning Theory. Technometrics 2020, 41, 377–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, V.; Mihai, C.T.; Cojocaru, F.D.; Uritu, C.M.; Dodi, G.; Botezat, D.; Gardikiotis, I. Vibrational Spectroscopy Fingerprinting in Medicine: From Molecular to Clinical Practice. Materials 2019, 12, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, A.C.S.; Martinez, M.A.G.; Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Advances in Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2017, 52, 456–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2008, 43, 134–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber, R.; Kowal, A.; Jakubczyk, P.; Arthur, C.; Łach, K.; Wojnarowska-Nowak, R.; Kusz, K.; Zawlik, I.; Paszek, S.; Cebulski, J. A Preliminary Study of FTIR Spectroscopy as a Potential Non-Invasive Screening Tool for Pediatric Precursor B Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Molecules 2021, 26, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlelmoula, A.; Pinho, D.; Carvalho, V.H.; Catarino, S.O.; Minas, G. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy to Analyse Human Blood over the Last 20 Years: A Review towards Lab-on-a-Chip Devices. Micromachines 2022, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitri, E.; Birarda, G.; Vaccari, L.; Kenig, S.; Tormen, M.; Grenci, G. SU-8 bonding protocol for the fabrication of microfluidic devices dedicated to FTIR microspectroscopy of live cells. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landari, H.; Roudjane, M.; Messaddeq, Y.; Miled, A. Pseudo-Continuous Flow FTIR System for Glucose, Fructose and Sucrose Identification in Mid-IR Range. Micromachines 2018, 9, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birarda, G.; Ravasio, A.; Suryana, M.; Maniam, S.; Holman, H.-Y.N.; Grenci, G. IR-Live: Fabrication of a low-cost plastic microfluidic device for infrared spectromicroscopy of living cells. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greener, J.; Abbasi, B.; Kumacheva, E. Attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for on-chip monitoring of solute concentrations. Lab Chip 2010, 10, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.; Zhang, K.; Xue, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, G. Review of MEMS Based Fourier Transform Spectrometers. Micromachines 2020, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).